By Bastiaan Willems

The storming of Fortress Königsberg in April 1945 was the finale of a two-month Soviet siege. The city, one of the few triumphs of Hitler’s fortress strategy, had been encircled by late January and lay hundreds of kilometers behind the main front line by the time the Soviets launched their final assault toward the Nazi capital of Berlin. Careful planning, economical use of matériel, and a close coordination during the assault eventually ensured the Soviet victory.

January 1945 had been a tough month for the troops of the Soviet Third Belorussian Front. Commanded by the young Army General Ivan Chernyakhovsky, they had been slogging their way through layer after layer of German positions since the beginning of their East Prussian offensive operations on January 13. Marked by a dogged and bitter German defense, the offensive through Germany’s most eastern province had been painfully slow. The gauleiter (political leader) and Reich Defense Commissar of the province, Erich Koch, had—in line with Hitler’s orders—demanded that every East Prussian village be “defended like a fortress, which the enemy could only take through durchfressen, by letting his blood flow.”

Casualty rates had indeed been shockingly high, but by late January, two weeks after the beginning of the offensive, the Soviet troops had managed to tear apart the two German armies that were defending East Prussia. The German Third Panzer Army and Fourth Army, which had been split into three pockets, stood with their backs to the Baltic Sea. One of these pockets—the one most feared by the Soviet Command and at the same time the most prestigious objective—was Fortress Königsberg. Lurking behind a fortress belt, the city, the capital of East Prussia, was considered the cradle of German militarism and fascism.

For centuries Königsberg had been one of the most important cities of Germany. Kings had been crowned there, and the philosopher Immanuel Kant had lived there his entire life. Conquering it would therefore not only be a strategic victory but also a significant setback for German morale. After its conquest, Königsberg would remain in Soviet hands. In November 1943, during the Tehran Conference, Soviet Premier Josef Stalin had insisted on making the city and the surrounding area part of the Soviet Union. For Chernyakhovsky’s men, however, that prospect still seemed remote that January. Little did they know that it would take over two months to capture the city.

On January 26, 1945, the first bombs started to fall on the city. Unlike the earlier East Prussian cities the Soviet Armies had come across, Königsberg had been designated a fortress, a Festung. Captivated by the idea of a stand to the last man, from March 8, 1944, onward Hitler had been designating key cities to become Festungen, and Königsberg was no exception to this policy. Koch, the advocate of a steadfast defense, fled Königsberg a few days later and would visit the city only a handful of times during the siege. Instead, at the head of its defense stood Festungskommandant (Fortress Commander) General Otto Lasch, a battle-hardened and well-respected soldier. Lasch doubted whether the city’s garrison would hold for more than a week but nevertheless started working energetically on his assignment.

On the evening of January 28, Soviet tanks stood only 10 kilometers from the city center and, much to Lasch’s surprise, decided to bypass the city and encircle it. A day later, the city was completely surrounded. Under Lasch’s command, two of the exhausted divisions that had withdrawn into the city, the 1st and the 5th Panzer, were completely revived as tanks were repaired in the city’s workshops and personnel were recruited from the local Hitler Youth.

Other divisions were patched up as well, Alarm-Einheiten (emergency units) were created, and the different Volkssturm units (Nazi militia) were placed under Lasch’s command. On February 17, 1945, after a little more than two weeks of restructuring the forces within Königsberg, Lasch received an order from the Third Panzer Army. As the garrison of the city was considered strong enough, it was ordered to assist Armee-Abteilung Samland in opening a corridor from Pillau, on the western tip of the Samland peninsula, to Königsberg.

Although Lasch considered it a gamble, he regarded it as necessary and allocated as much force as possible. When successful, the corridor would allow civilians to escape the city and food and reinforcements to come in. The Germans would attack the flanks of the exhausted Thirty-ninth Army of Ivan Lyudnikov, which after a demanding advance had taken up positions on the Samland along the Frische Haff. On the morning of February 19, the attack, code-named Westwind, commenced. The German divisions on the western tip of the Samland attacked east, while the divisions from Königsberg pushed west. On the afternoon of February 20, the two groups linked up and eventually recaptured an area of almost 200 kilometers, a stunning achievement.

outskirts of Königsberg on January 20, 1945.

The fighting in the corridor continued for another week, leaving the Thirty-ninth Army severely battered, after which both belligerents dug in along the new front line. The gamble had paid off handsomely. That week, the defenders of the fortress managed to inflict yet another major blow to the Soviets. On February 18, a shell fragment killed General Chernyakhovsky, leaving the Third Belorussian Front temporarily without a commander.

Early in the morning of February 22, two Soviet commanders discussed the plans for the elimination of the German troops in East Prussia. Just a few days earlier, both had held different positions, although there was little reason to feel uneasy in their new roles. The first was Marshal Aleksandr Vasilevsky, who replaced Chernyakhovsky. Marshal Vasilevsky had been chief of the STAVKA (the Soviet General Staff) before his appointment as commander of the Third Belorussian Front and was therefore, like no other, aware of the situation in East Prussia. Earlier that month, he had asked Stalin to give him a position in the field, and now he was had the chance to prove himself.

The other man was General Ivan Bagramyan, who was appointed second in command of the Third Belorussian Front. Only hours earlier, he had been commander of the First Baltic Front, which was being disbanded. Its armies, from that time on designated as the Samland Group, were absorbed in Vasilevsky’s Third Belorussian Front, which as a result totaled a massive 10 field armies and two air armies.

The main motivation for the merging was rather simple: having all armies under a single command would allow manpower and equipment to be maneuvered more easily. “Our task,” Vasilevsky explained to Bagramyan, “is while having only a slight overall superiority, to achieve an overwhelming superiority in those areas where we are going attack the enemy.”

East Prussia had to be captured one chunk at the time. The biggest chunk was for Vasilevsky, who had to destroy 26 German divisions trapped in the Heiligenbeil pocket. In the meantime, Bagramyan was given the task of capturing Königsberg and the rest of the Samland. Unlike the German units in the Heiligenbeil pocket, the majority of the troops around Königsberg could rely on earlier prepared fortified defensive positions. Overcoming them would require extensive interaction between all branches of his Armies.

Several of the units Bagramyan received to capture Königsberg had been deppleted by the East Prussian offensive. Lyudnikov’s Thirty-ninth Army, which lay to the northwest of the city, had been involved in the fighting from the beginning of the offensive. Its strength had been diminished by almost half, and the German breakout of mid-February had weakened the army even further. Of the Forty-third Army, which had been fighting from January 22 onward, only 23,000 of the initial 80,000 remained. It had taken up positions north and east of the city, as a German attack in that direction was unlikely. The Eleventh Guards Army lay south of the city. It had been in action the shortest of the three armies, but on its path through East Prussia it had encountered the most opposition. The state of their troops made all Soviet commanders deem a swift attack on the city as hopeless, and Bagramyan ordered his troops to go on the defensive.

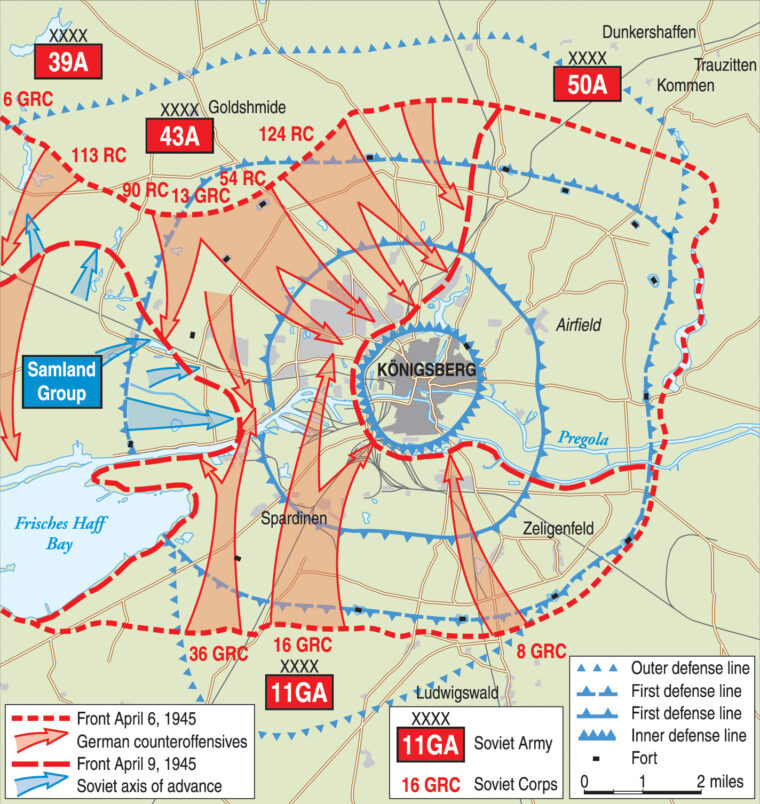

Sooner or later, however, the Samland Group would have to go on the offensive. Bagramyan and his chief of staff, Colonel General Vladimir Kurasov, drew up a preliminary plan, using the Thirty-ninth Army to cleave through the city’s outer defensive ring from the northwest to separate the fortress from the Samland. Simultaneously, the Eleventh Guards Army was to break through the outer ring from the south. The Forty-third Army was given the task of capturing the northern and eastern parts of the city.

On March 7, Marshal Vasilevsky brought some good news to the Samland Group. He was able to free the small Fiftieth Army from the fighting at Heiligenbeil to assist in the storming of Königsberg and assured Bagramyan that he could count on the support of all aircraft present in East Prussia, some 2,500 planes.

Although Vasilevsky was preoccupied with the fighting for the Heiligenbeil pocket, he had given serious thought to the capture of Königsberg as well. Since Lyudnikov’s army still had not fully recovered from the damage of the German counterattack, he decided it would not take part in the actual fighting for the city. For Lyudnikov this was a huge disappointment, since, in the words of Bagramyan, “Lyudnikov had been dreaming about it, seeking revenge for the latest setback.”

Instead, the army was to capture a small but vital area west of the city to prevent the German troops in the Samland from assisting in its defense and prevent an escape of German troops from Königsberg. A major role in the capture of the city was given to General Afanasii Beloborodov’s Forty-third Army instead. His troops were to seize the northern and northwestern parts of Königsberg and advance to the heart of the city. Given its small size, the Fiftieth Army had been assigned to capture the eastern suburbs of the city. Lastly, the task of the Eleventh Guards Army remained the same: capturing the entire southern half of the city.

Hitler’s generals had always dismissed fortress strategy as incorrect, but Königsberg showed that it could certainly yield results. Five worn-down German divisions (this number varied throughout the period) contained four Soviet armies, an astonishing achievement. Königsberg owed a lot to its outer defensive ring of late 19th-century forts, which had been connected by a vast maze of trenches. Despite the fact that all the casemates and forts were outdated, they served as the backbone of the defense and housed a considerable number of defenders.

Soviet aerial reconnaissance photographed the city some 10 times to keep up to date, and the front command had a 36-square-meter electrical relief model of Königsberg and its defenses constructed to study German positions in depth. To prevent the evacuation of German troops, the Baltic Fleet mined the Königsberg channel between Pillau and Königsberg. Lectures on the political and military importance of Königsbergor were held for officers participating in the siege. Reinforcements were coming from as far as the Ukraine and Moldova.

There was little doubt among the troops that the storming of the city would be brutal. Thousands of them would lose their lives, and indulging themselves in the available pleasures of confiscated alcohol while they still had the opportunity seemed perfectly logical.

Until the end of March the Soviet soldiers had been observing the city, knowing that they would soon receive the order to storm it. “You know, I am often looking in the direction of Königsberg,” wrote nurse Anna Michajlovna, “It is clearly visible. You can distinguish yards, a monastery, plant chimneys and trees. When I look at the city of Königsberg, it reminds me of Stalingrad—the heroic city, the city of glory.”

Lasch, in the meantime, was working feverishly to improve the defenses of the city. He enforced iron rule upon the remaining population (some 130,000) and had every able body contribute to it. Men were forbidden to leave the city without notification; women and children were little better off as measures for evacuation were extremely poor. There was a dramatic increase in court-martial cases and death sentences. Public executions were the order of the day, performed by the Army, the Nazi Party, and the SS. On the other hand, some 900 prisoners were released from jail in the earliest stage of the siege under the condition that they contribute to the defense of Königsberg. Despite the harsh situation, many inhabitants decided to stay in the city. Even after the creation the corridor between Königsberg and Pillau, relatively few people left as horror stories about the appalling conditions in Pillau and tales about the sinking of large ocean liners filled with refugees spread. In Königsberg, at least, there was no scarcity of food and drink; even a cinema and the banks were open.

During March, the Soviet troops started their buildup for the assault on Königsberg, moving matériel to designated areas. For the Germans, a shortage of artillery shells meant they had to watch powerlessly and could do little to stop it. Lasch believed an attack on the fortress was imminent. His superior, General Vincenz Müller, the commander of Army Group North, was of a different opinion. He estimated that the Soviets would strike first in the direction of Pillau, thereby cutting off the entire Samland and blocking the escape route to the Reich.

Therefore, in late March, General Müller decided to remove the two most battleworthy divisions from Königsberg, the 1st and the 5th Panzer, which were placed farther west on the Samland peninsula. These divisions were the two Lasch had worked so hard on to get back into shape, and their departure from the city made him lose all hope for its retention. He asked to be relieved of his position as fortress commander.

Müller, annoyed by Lasch’s complaints, assured Lasch that he would soon be relieved. The last thing the fortress needed was a defeatist commander. For Lasch, unfortunately, his relief would not come in time.

The units that remained in Festung Königsberg by late March were two worn-down infantry divisions, the 69th and the 367th, and two Volksgrenadier divisions, the 561st and the 548th. They were supported by two Kampfgruppen (battle groups), Mikosch and Schubert, and some 5,000 men of the Volkssturm. In total, the defenders numbered, according to a report to the German high command, some 47,800 men. Furthermore, the fortress possessed 224 artillery pieces but a mere 16 self-propelled guns.

Even when taking into account that by early April the defenders were joined by the staff of the 61st Division and that the 5th Panzer Division would assist in the defense of the city as well, it was perfectly clear that these numbers were completely insufficient to halt the Soviet storm. Opposing the Germans were 36 rifle divisions, two mortar divisions, and five artillery divisions, as well as six antiaircraft divisions supported by an armada consisting of 41 aviation divisions. Although the Soviet divisions were considerably smaller in size than their German counterparts, the odds were indisputably in favor of the attackers.

By late March, everyone in Königsberg believed the storming of the city was just days away. Soviet planes had been dropping leaflets over the city stating that the people could celebrate their Easter but after that their days were numbered.

Eventually, the Soviets kept their word. The day after Easter, April 1, was foggy and grounded the Red Air Force. The artillery, nevertheless, went to work, gradually increasing in intensity. Some 5,000 guns and mortars, together with 300 rocket launchers, started to stir. Half of this might consisted of large-caliber guns, including guns ranging from 203mm to 305mm. During the first day of the artillery bombardment, the artillerists mainly used small-caliber guns to remove the “pillow” of earth from the forts. During the next three days, heavier guns destroyed communications, pinned down the German defenders in their bunkers, and demolished some fortifications.

Meanwhile, at Vasilevsky’s headquarters, the last preparations were being made for the attack. As of April 3, the Samland Group was disbanded, and its troops were absorbed by the Third Belorussian Front. Vasilevksy, as the front commander, would oversee the assault on Königsberg, although Bagramyan stayed closely involved. By the end of the day, the bad weather showed no sign of improvement, and Vasilevsky called Stalin to ask for instructions. After the phone call, he told the awaiting Bagramyan and his staff, “He wants us to make haste. The Berlin operation is close on our heels, you know…. We must get going.”

On the morning of April 6, Bagramyan was near the little town of Fuchsberg, a short distance from Königsberg. Just when he was put through on the phone to report to Vasilevsky about the outcome of a reconnaissance effort, he heard “intermittent booming noises” coming from the opposite side of the city. “Katyushas [rockets] were heralding the start of the artillery preparations by the Eleventh Army. They were seconded by a chorus of heavy guns. Although the explosions were a long distance away, I could see the glass vibrating in the window panes.”

It was the last preliminary bombardment, three hours prior to unleashing the ground troops at noon. The morning fog prevented Soviet aircraft from operations that morning, but it hardly dampened Vasilevsky’s spirit. “Good music, isn’t it?” he asked Bagramyan. “I only wish I could also hear the airmen.’”

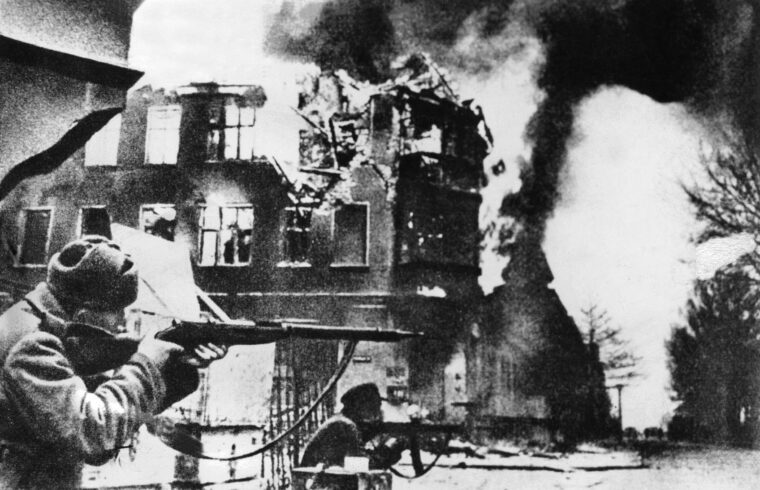

Heavy fighting started as soon as the artillery stopped. In the south, soldiers of the Eleventh Guards Army had been crawling toward the front line while the shells were still falling. Within minutes after the barrage stopped, they were grimly fighting. On the flanks of the Soviet advance lay two forts on the left, Fort VIII and Fort Friedrich Wilhelm IV. On the right was Fort X, also known as Kanitz. In January, Soviet troops had taken Fort IX, known as Donha, which lay in between.

The German garrisons resisted fiercely, and it was decided that the first wave of attack would move around them, leaving their capture to the second echelon, a tactic that was followed throughout Königsberg. The two forts were cause for concern, but the bulk of the army could successfully moved into Königsberg’s southern suburbs, Prappeln and Ponarth.

There, the Soviets were temporarily halted by camouflaged antitank guns and tanks dug into the ground. Against the initial plan, Eleventh Guards Army commander General Kuzma Galitsky decided to commit his entire second echelon to join the battle in the late afternoon. By that time, the weather had improved somewhat, which meant that the Army aircraft could assist. By the end of the day, Galitsky could proudly report that his troops had advanced four kilometers, which made the day a success for the army.

To the north, the day progressed successfully as well. The Forty-third Army had completely cleared Charlottenburg, the northernmost suburb of the city, despite the fact that Lasch had committed the fortress reserve in that area. Furthermore, the Soviets had encircled two forts, Friedrich Wilhelm III and Lehndorf.

In the northwest, the Thirty-ninth Army advanced somewhat slowly as it was repeatedly counterattacked by the 5th Panzer Division. Nevertheless, it managed to cut the railroad from Königsberg to Pillau, although the highway to its south remained in German hands. The right flank of the Fiftieth Army, bolstered by the First Tank Corps, dislodged the defenses in the suburb of Beydritten and stormed Fort Gneisenau. On its left flank, one of the Fiftieth Army’s three corps was used to pin down the garrisons of five forts, Quednau, Barnekow, Bronszat, Groeben, and Stein, consolidating Soviet gains northeast of the city into a continuous line. The Fiftieth Army movement prevented the German 367th Division from participating in the defense of other vital areas.

During the day the weather cleared up, and in the afternoon the air force could for the first time operate in full strength. The daily deployment of 2,500 aircraft was a masterpiece in itself. The First, Third, and Fifteenth Air Armies came from the south, east, and north, while planes from the Baltic Fleet came from the west. Long-range bombers came from all sides.

Late on the night of April 6, Soviet troops attacked Fort Lehndorf. Self-propelled 122mm guns were brought in, firing point-blank at the fort. This proved too much to bear for the defenders, and the 200 remaining men capitulated.

The next day, April 7, started with a brief but powerful artillery barrage. Beloborodov’s army advanced into the suburb of Juditten and continued toward the city center. But later in the day the Soviet advance came to a halt in the suburb of Hufen. In the fighting for the Beydritten suburb, the Fiftieth Army also slowed down considerably. It had advanced only about 11/2 kilometers. The Forty-third Army’s progress was even more disappointing and could be measured only in hundreds of meters.

To the west, Lyudnikov’s Thirty-ninth Army also advanced painfully slowly. By the end of the day, it had still not managed to cut off the city from the rest of the Samland but instead had to fight off some 18 counterattacks from the 5th Panzer Division. However, the sluggish advance of these three armies did not mean that the day had been unsuccessful for the attackers. They occupied most of Königsberg’s reserves, which meant that the Eleventh Guards Army in the south could make good headway.

The German defenders zealously held onto every city block, but the overwhelming Soviet superiority in men and arms took a heavy toll. To make matters worse, the pleas of the fortress command to the Fourth Army to use the 5th Panzer Division to check the Thirty-ninth Army were initially granted, but as Lyudnikov’s men were attacking the 1st Division west of the city as well, 5th Panzer was redirected there and its support of the fortress was called off.

Soviet troops, meanwhile, were advancing through the southern suburbs. On their right flank, the 8th Corps was able to make considerable progress. The German defenders had to give up the small suburb of Schönfliess, while Fort Kanitz fell as well. By the end of the day, the corps had advanced toward Rosenau, a suburb directly adjacent to the city center. The swift capture of this large area was a fine result, but it was no surprise.

Lasch and Müller gave absolute priority to retaining a connection to the Samland west of the city, and the majority of the German forces were deployed there. It was perfectly clear to Lasch that when the Soviets crossed the Pregel River in the western part of the city, Königsberg would be lost within a matter of hours. On the left of the advance, therefore, two other Soviet corps encountered much heavier resistance. Battle Group Schubert, a unit mainly consisting of police and SS units, defended the Nasser Garten suburb just south of the river.

To impede Soviet progress, the Pregel had been allowed to flood the area when the attack on the city began. Unfortunately for the defenders, this decision worked to their disadvantage. Battle Group Schubert was destroyed. To the east, the German 69th Division was slowly being driven out of Ponarth, and by the end of the day its units were fighting at the southern edge of the city center. The major strongpoint in this area was the Hauptbahnhof, the main railway station, at which the fighting erupted in the late afternoon. Unable to break the resistance around the station with two first-echelon divisions, the commander of the 16th Guards Corps deployed his final division, the Eleventh Guards Division of his second echelon, which meant that the entire corps was eventually fighting for the area. The battle lasted well into the next afternoon.

The Soviets were unable to cross the Pregel, and the Eleventh Guards and Forty-third Armies had still not linked up. Nevertheless, half of Königsberg had been captured by the Eleventh Guards Army by the night of April 8, while another quarter had been captured by the Forty-third and Fiftieth Armies.

To prevent a Soviet linkup, Battle Group Mikosch was brought in from the still relatively quiet eastern sector, leaving its defense to elements of the 367th Infantry Division. Nevertheless, after the Soviet 36th Corps had managed to clear the area south of the Pregel, its forward elements, supported by aircraft, started to cross the river that night. The rest of the corps followed the next morning.

The Soviet 8th Corps was embroiled in fierce fighting for the suburbs of Rosenau and Jerusalem. Although the German defenders were few in number and had to give up large areas, they were able to inflict heavy casualties. As a result, the corps reached the Pregel by the end of the day but did not have the manpower to cross it.

At the same time, the suburbs of Amalienau and Ratshof, just north of the Pregel, were attacked by Beloborodov’s troops, whose 13th Corps was to join up with Galitsky’s men. His 0th Corps was fighting somewhat to the west and was clearing out Juditten while simultaneously fending off counterattacks from the Samland.

The pressure from the peninsula became so powerful that Vasilevsky decided to withdraw some of Beloborodov’s divisions from the fighting in Königsberg and place them west of the city to block German units from the Samland.

As Galitsky’s troops were already partly over the river and Beloborodov’s troops had diminished in strength as a result of Vasilevsky’s order, the linkup between the two armies was set to take place in Amalienau, just west of the city center. To prevent friendly fire, the artillery and the air force were ordered to divert their operations from the suburb. The last pockets of resistance in this area had to be eliminated in hand-to-hand fighting.

By 2 pm, the two Soviet armies had linked up, and the garrison of Königsberg was surrounded. Almost immediately, Vasilevsky ordered leaflets dropped over the city urging the Germans to lay down their arms. The offer was ignored.

Lasch was asked to consider a breakout attempt, but he hesitated. The army commanders managed to contact Gauleiter Koch, who convinced General Müller to give his authorization. Müller wanted to hold on to Königsberg at all costs and allocated only minor elements of the 561st Volksgrenadier Division to the attempt. Lasch knew that the chance of success was limited. He committed parts of the 548th and the remnants of the 61st Division, as well as the majority of the available artillery, to form a corridor. The party was given the task of leading the civilians out of the city.

At 11 pm, the units received the order to advance toward their starting positions, but the destroyed city made orientation hard and movement even harder. Only at 2 am did the attack finally commence. From the onset, the rubble forced the units to disperse and lose contact. Before long, no group comprised more than 50 men, which made them easy prey for the Soviets.

Eventually, some of these groups did manage to break through the Soviet encirclement, but a safe corridor was impossible to establish. Large groups of civilians were targeted by Soviet artillery, turning their evacuation into carnage. Surviving civilians and soldiers fled back to the city. The attempt had failed.

Stubborn fighting continued throughout the night and into the morning. Despite their best efforts, the German defenders had no choice but to slowly fall back toward the inner city. After the capture of the Amalienau suburb, Galitsky’s troops pushed northeastward, capturing the large Luisenwahl cemetery and the Tiergarten (zoo) and continuing to the southern tip of the Oberteich in conjunction with the 54th Corps of the Forty-third Army.

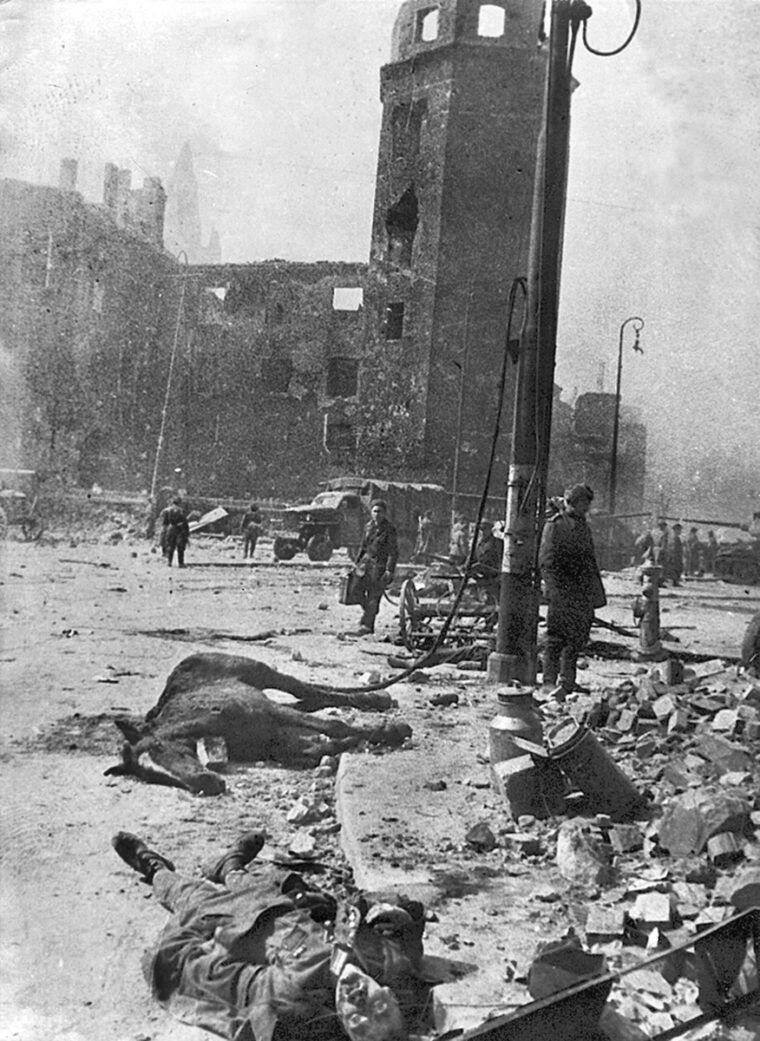

The remaining elements of Galitsky’s army crossed the two arms of the Pregel south of the city center. By the morning of April 9, the core of the defenders had been driven into the last line of defense, a series of forts that surrounded the old city center, a mere four square kilometers. By that time, the German 69th, 548th, and 561st Divisions had been destroyed. Remnants of the 61st Division were positioned in bastion Sternwarte to the west, while the 367th Division had taken up positions in and around bastion Grolman. The southern sector was defended by Battle Groups Schubert and Mikosch.

East of the city center, two corps of the Fiftieth Army encountered little opposition north of the Pregel and were able to clear the entire area to the northeast and east of the city center. The 69th Division took the five forts, a third of all forts of the outer ring, virtually without a fight.

In the west, the Forty-third Army was to assist the Thirty-ninth Army, which was still fighting off elements of the 5th Panzer Division, with two of its corps. Beloborodov’s army was to regroup and attack along the Frische Haff to speed up the destruction of the remaining German troops in the Samland. His army captured Fort Königin Luise and Herzog v. Holstein. By the morning of April 9, Soviet troops started penetrating the last line of defense in force. Lasch decided to open surrender negotiations.

As German troops were being cut off from the Samland, separated by a five-kilometer gap, Lasch knew that no help would be forthcoming. His troops lacked even the most basic ammunition and provisioning, and a cessation of the fighting could perhaps save lives. In the afternoon, he discussed the possibility of capitulation with his staff. A little later he announced his decision to the divisional commanders he was able to reach.

The next step was to reach the Soviets, and Lasch sent messages to the commanders of strongpoints and divisions, urging them to establish contact whenever possible. One of these commanders was an Oberstleutnant (lieutenant colonel) Kerwin, the commandant of the Trommelplatz Kaserne.

Shortly after midday, he received a letter written by Lasch. “My dear Kerwin! I have decided to surrender because I have no more connection with the troops. The artillery is without ammunition and I cannot justify further bloodshed and this terrible strain on the nerves of the civilian population. Try to get into contact with the Russians. Have them immediately cease fire in order to send a peace envoy to me, so I can surrender Königsberg.”

Delivering this letter to the Soviets was the task of three envoys, Rittmeister Steincke, Hauptmann Georges, and Feldwebel Gramlow, but the task proved easier said than done. Even though they carried a white flag, they were almost immediately fired upon by Nazi Party members, who had taken up positions nearby. Kerwin received a message that all three had died. He sent two more men, who were also fired upon by the same group.

Shortly afterward, some of the party members stormed into the Trommelplatz Kaserne. “Where is Oberstleutnant Kerwin? He has to be shot! He is sending peace envoys to Ivan. He has to be court-martialed!”

After hearing that Kerwin acted on Lasch’s orders, the men calmed down somewhat. A little later, much to Kerwin’s surprise, he was summoned to a store, where a Russian messenger was waiting. One of the men of the first group had actually managed to get through the lines, and Kerwin was being sent for personally. At 7 pm he arrived at the headquarters of the Eleventh Guards Division, where its commander, General Tsyganov, was already waiting. The lack of Lasch’s original letter made the atmosphere between the two men tense, but in the end Kerwin managed to convince the Soviet officer that his mission was genuine. Tsyganov notified Galitzky. Galitzky reported to Vasilevsky, who gave permission to accept the capitulation.

At 10 pm, guided by Kerwin, the chief of staff of the 11th Division, Lt. Col. Janowski, together with Captains Fedorenko and Spitalnikov, was dispatched to deliver the ultimatum for an unconditional surrender to Lasch.

Half an hour later, Kerwin reported to Lasch: “General, I have executed, as ordered, the saddest task of a soldier. Here is the Russian envoy.”

Within 15 minutes the ultimatum was signed. At 10:45 pm, Lasch ordered the immediate cessation of resistance. Not all of his subordinates, however, acquiesced in this decision. On the morning of April 10, after hearing the city had capitulated, the men of Kampfgruppe Schubert declared Lasch to be deposed and appointed one of their own officers as his successor. The remainder of the battle group, some 150 men, decided to occupy the old castle of Königsberg and fight to the last bullet.

By then, Soviet tanks had already reached the adjacent square and started shelling the building. Casualties mounted. Some Germans surrendered. Those who attempted to escape the carnage were wiped out.

Senior German commanders were brought before their Soviet counterparts for interrogation in the early afternoon of April 10. Lasch, who had just heard that his family had been imprisoned as a result of his capitulation and that he had been condemned to death in absentia by Hitler, had much to worry about. He had been backstabbed by Gauleiter Koch, who had barely been in the fortress during the siege but now managed to profit from the capitulation.

In a shameless wireless message to Berlin, Koch had turned the events completely upside down. “The commander of Königsberg, Lasch, has used a moment of my absence of the fortress to cowardly surrender. I’ll continue to fight on the Samland….”

The Soviet high command abhorred the decision of the “imbecile Führer,” and thought highly of Lasch. As Lasch was quite willing to answer questions, Vasilevsky diverted somewhat from protocol and asked him to evaluate the outcome of the battle.

“It was impossible to know beforehand that a fortress like Königsberg could fall so soon,” Lasch bitterly admitted. “The operation has been well prepared and executed by the Russian high command.”

Lasch was correct in his assessment. As a result of careful Soviet planning and execution, the fortress, which had been besieged for over two months, eventually fell within four days.

Bastiaan Willems is resident of the Netherlands. This is his first contribution to WWII History.

Join The Conversation

Comments