By Nat R. Louis

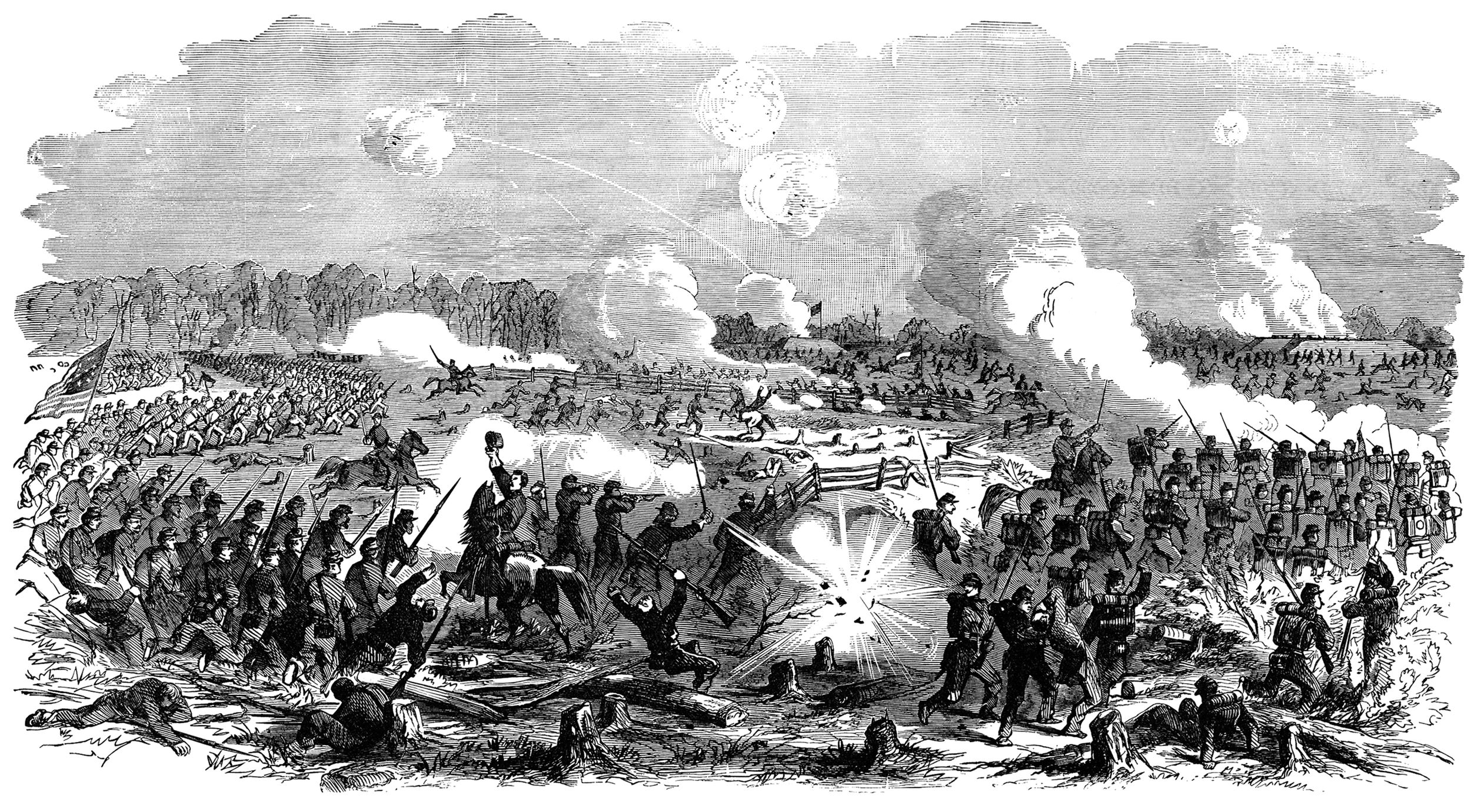

During the Battle of Williamsburg, Virginia, in May 1862, General Joseph Hooker’s Union forces were in pursuit of the withdrawing Confederates. Although slowed by rain and mud, Hooker’s troops attacked Fort Magruder, the strongest section of the Rebel lines. Lending support on the Confederate right was a mountain artillery unit that had been drilling for only three weeks.

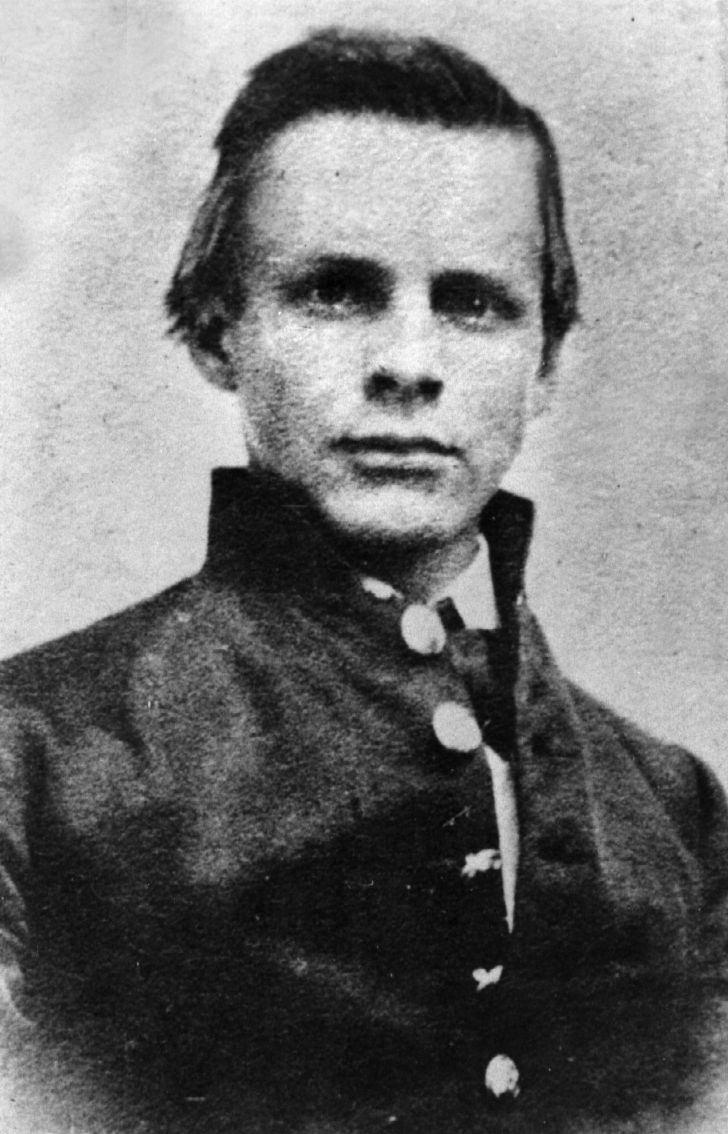

The young leader of the battery, John Pelham, was complimented on his coolness under fire. Before the end of 1862, the planter’s son from Alabama would be known as “The Gallant Pelham,” and would redefine the concept of the flying battery for Confederate artillery.

Born in Benton City, Alabama, in 1838, Pelham was a descendant of the American painter Peter Pelham. His early years were spent like many Southern boys—school, horses, athletics, and exploring the outdoors. He enrolled in an experimental five-year curriculum at West Point in 1856. While there, he was considered the best athlete and was noted for his fencing and boxing. But he was especially remembered for his skill as a horseman, even drawing praise from the Prince of Wales, who visited West Point in 1860.

On April 22, 1861, within weeks of graduation, he resigned from West Point and entered Confederate service as a lieutenant and ordnance officer posted to Lynchburg, Virginia. It is said that he was able to get through the Union lines into Kentucky with the help of a woman in Indiana whose affections he won.

At the First Battle Of Bull Run Pelham’s skills were noticed by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, who immediately promoted him to captain owing to his vast knowledge of artillery tactics, at which he had excelled under Maj. Henry J. Hunt at West Point.

Pelham was with Gen. “JEB” Stuart’s Horse Artillery during the battle of Gaines’s Mill in June 1862 and was dispatched into the night to uncover a position from which he could sweep the James River Road. Stuart was anxious to know if Union Gen. George B. McClellan was extending his lines northward, and needed the information by morning. Before dawn, Pelham informed Stuart that the Union troops were near the famous Byrd mansion at Westover. It was dominated by a long ridge line called Evelington Heights. Pelham suggested that his artillery be placed on these heights. Stuart agreed.

Scattering some Union cavalry already on the spot, Pelham positioned his lone gun on the heights. With the cry of “Let them have it,” the little howitzer barked and sent shells screaming at a group of unsuspecting teamsters, although with little effect. However, Pelham’s barrage did give Stuart time to pass on information to Lee that the Union Army was camped under the heights adjacent to the river. Soon, Rebel sharpshooters situated themselves alongside the little gun to harass a Yankee advance forming on their flank.

Despite his heroics, Pelham was forced to flee when he exhausted his ammunition and a Union battery suddenly appeared east of Herring Creek. With Longstreet six or seven miles away, any attempt to hold the heights would prove futile.

Pelham was showered with praise by Stuart who wrote in his report: “The only artillery under my command being Pelham’s Stuart Horse Artillery, the 12-lb. Blakely and Napoleon were ordered forward to meet this bold effort (at Gaines’s Mill) to damage our left flank. The Blakely was disabled at the first fire; the Union forces opening simultaneously with eight pieces, proving afterward to be Weed’s and Tidball’s batteries. Then ensued one of the most gallant and heroic feats of the war. The Napoleon gun, solitary and alone, received the fire of these batteries, concealed in the pines on a ridge commanding its ground; yet not a man quailed, and the noble captain directing the fire himself with a coolness and intrepidity only equaled by his previous brilliant career … the Napoleon clung its ground with unflinching tenacity.”

Upon learning of Pelham’s action, General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson reinforced the Horse Artillery with several batteries of rifled pieces. From then on, it was Pelham’s Flying Battery that made a name for itself. It was Pelham who cleared the way for Stuart’s advance to White House Landing; Pelham who chased the USS Marblehead down the Pamunkey River; Pelham who challenged the Federals across the Chickahominy; and Pelham who, at Stuart’s call, opened fire from Evelington Heights. The young officer was modest when presented to General Jackson, who gravely shook his head. Pelham bowed deeply and blushed as he was recommended for promotion to major by Stuart.

At the Second Battle of Bull Run, it was Pelham’s three pieces of artillery that were sent for by Jackson and which saved the day for the Confederacy. For two-and-a-half hours, the artillery of both sides exchanged broadsides.

And so it was at the Battle of Antietam in Maryland. Although Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was cornered and eventually quit the field, it was Pelham’s artillery that won the honors. Even though they were outranged, outgunned, and exposed to Union shelling, Pelham performed magnificently. A dominating hill on Jackson’s left was considered necessary to hold the advanced line of battle. And Major Pelham was there with his Horse Artillery matching the Yankee guns, salvo for salvo.

On October 12, 1862, Stuart selected 1,800 of his most reliable cavalrymen for an incursion into Pennsylvania. Pelham was put in charge of the four guns of Stuart’s Horse Artillery. When the raid was ready to get under way, he set two guns in front of the column and two in the rear. Upon their return from the Chambersburg raid, Stuart’s gray riders confronted union horsemen on the road from Beallsville. Without hesitation, Pelham deployed a pair of his pieces and swung them into action. He saw a crest that overlooked not only the road, but all approaches to White’s Ford, Stuart’s avenue of retreat. Pelham unlimbered his Napoleon and covered Stuart’s crossing. After all the riders were across, he did likewise. Once again, the Pelham demonstrated his swiftness and intelligence, his trademarks since the Battle of Williamsburg.

Near Union, Virginia, in November 1862, Pelham again distinguished himself by boldly advancing one of his howitzers beyond a point where Stuart could support him. The quick-thinking Rebel found a covered niche and commenced a bombardment on a column of Yankee cavalry, causing them to break into a headlong flight. Close behind, Pelham’s mounted cannoneers picked up discarded equipment and other “booty” as souvenirs.

A month later, in December 1862, at Fredericksburg, Virginia, young Pelham distinguished himself again. With a Blakely rifle and his 12-lb. Napoleon, the indomitable Confederate set out for the intersection of the Richmond Stage Road. Though risky, from this vantage point he could let loose his artillery upon any troops moving against Jackson.

Pelham didn’t have to wait long before a flanking party of infantry was spotted marching toward them. Excited at the prospect of engaging infantry, the Alabamian fired solid shot into the blue-clad ranks. But answering Union artillery crippled Pelham’s Blakely. Left with just the Napoleon, the crew fired and reloaded it so fast that the Union forces thought they had encountered an entire battery of guns.

Impressed by Pelham’s deed, Stuart nonetheless instructed his staff officer Maj. Heros Von Borcke, to tell Pelham to withdraw. Disregarding Stuart, the fearless Rebel told Von Borcke he could hold his position. As his men were killed and wounded, the dauntless major continued to shift his Napoleon, reloading until the Yankee attack seemed to lose its momentum. Stuart again sent word but, as before, Pelham maintained his post. Finally, out of shot, Pelham was forced to abandon his location. As Yankee rounds crashed all around him, Pelham backtracked to Hamilton’s Crossing.

Peering through his field glasses, Lee asked to what battery that gun belonged. Hearing it was Pelham’s, the Virginian responded: “It is glorious to see such courage in one so young.”

Bolstered by artillery from General A.P. Hill’s command, Pelham hastily repositioned his Napoleon to further impede the Federal advance that was beginning to mass. At 1 p.m., the Union batteries launched a furious cannonade. Hill’s 14 guns, coupled with the spunky little Napoleon, returned the fusillade. As the blue surge assaulted their lines, Pelham’s guns on the right and Maj. Reuben Walker’s pieces on the left ripped into the Yankee columns. Crossing their fire, the butternut cannons repulsed the Union attack. Word spread swiftly of the Alabamian’s courage under fire and it was about then that he was christened “The Gallant Pelham.”

During Stuart’s Dumfries Raid later in the month Pelham, to the astonishment of all, drove his guns through the Occoquan River at Selectman’s Ford which was considered by many to be impassable. Stuart heaped praise on his young major for keeping pace with his cavalry and many wondered if the bold Confederate could do no wrong. He pursued the enemy with his field pieces as if they were cavalry and others regarded him as a genius in the deployment of artillery.

Despite all the adulation, Pelham was modest. He never spoke of himself or his exploits and his eyes “gentle and merry … were lighted with friendship.…” He once confided in a friend that he “was not destined to be killed in the war.” He was “tall and slender, beautifully proportioned, with golden hair, and dazzling blue eyes.” Constantly admired by the ladies, Pelham was “as grand a flirt as ever lived.”

When not with his beloved artillery, Pelham spent considerable time with Stuart at his headquarters. The two shared a strong friendship, with Stuart looking after the younger Pelham as an older brother would.

An avid reader, Pelham studied the Bible and other classics. His tent was next to that of William Blackford, Stuart’s chief engineer, and the two enjoyed long conversations. Clearly Pelham was a rising star. Numerous people predicted the young Confederate would be promoted to lieutenant colonel and then to brigadier general by spring.

But as that spring dawned, on the morning of March 17, 1863, Stuart received alarming reports of large numbers of Union troops marching in the direction of Culpeper. Arriving at Stuart’s field headquarters, near Kelly’s Ford, Pelham waited for one of his batteries that had been temporarily attached to Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee. Together with Stuart and Lee, Pelham rode toward Kelly’s Ford from the west, where Rebel pickets discovered the Federal forces. As the gray-clad sharpshooters started to harass the bluecoats, Pelham reconnoitered to determine an advantageous position for his artillery.

Returning, Pelham saw the action was developing at a fast pace. Stuart was rallying his men and pressing them forward. When Pelham witnessed the 3rd Virginia Cavalry charging pell-mell at a stone wall that was acting as cover for the Union forces, the impetuous youth drew his saber and joined them. Cutting across the field to lead the assault, Pelham shouted: “Charge!” Finding an opening in the stone barrier, the butternut horsemen attempted to outflank their blue counterparts.

Pelham belted at the gate and cried encouragement to the cavalry as they galloped ahead. Waving his saber in the air, he stood upright in the saddle with a broad smile and a look of sheer ecstasy on his face as the Confederates began routing the Yankees.

An explosion caused Pelham’s horse to buck, throwing the youth from his saddle. Lying motionless, face up, with the smile still on his lips, “The Gallant Pelham” was apparently dead.

When informed of Pelham’s death, Stuart lowered his head and muttered: “Our loss is irreparable.” But, upon closer examination, attendants discovered that Pelham’s heart was still faintly beating. The major’s body was quickly transported to the home of a woman he had wooed and to whom he was engaged, Bessie Shackelford in Culpeper. A trio of surgeons found that a tiny piece of shrapnel, no larger than the tip of a little finger, had entered through the back of his skull just above the hairline. It had done irreversible damage to the nerves.

Early in the afternoon of March 17, Pelham opened his eyes, drew a long breath, and passed away. It is now widely believed that if surgical aid had been given sooner, Pelham’s life could have been spared.

At Hanover Junction, Major Heros Von Borcke met the train that carried Pelham’s body and accompanied it on to Richmond. At the Confederate capital, Pelham’s body was placed in a metal casket and laid in state. A small window was built into the top of the coffin so his admirers could view him one last time. Amid a multitude of flowers, the citizens of Richmond lined up to pay their final respects. A guard of honor was detailed to escort the remains back to his home state of Alabama.

Lee proclaimed: “I mourn the loss of Maj. John Pelham. I hope there will be no impropriety in presenting his name to the Senate, that his comrades may see that his services have been appreciated, and may be incited to emulate them.” It was as a lieutenant colonel that Pelham went home.

He was buried in Jacksonville, Alabama, southeast of Gadsden. At the graveside, a family member said: “I heard a voice near me say, ‘made white in the blood of the Lamb’ and I knew it to be the voice of his mother. The father and sister were crushed and stayed in their rooms but the spartan mother met her beloved son … and directed that he … be laid where the light would fall on his face when Sunday came.”

In Stuart’s general order to the division, announcing his death, no finer tribute could be more applicable to the gallant Pelham; it concluded “that he was calmly and recklessly brave, and saw men torn to pieces around him without emotion, because his heart and eye were upon the stern work he was performing.”

In the ensuing years, Southern writers immortalized the heroic accomplishments of the brave, young Confederate major who improvised the use of artillery as an important supporting arm of the cavalry.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments