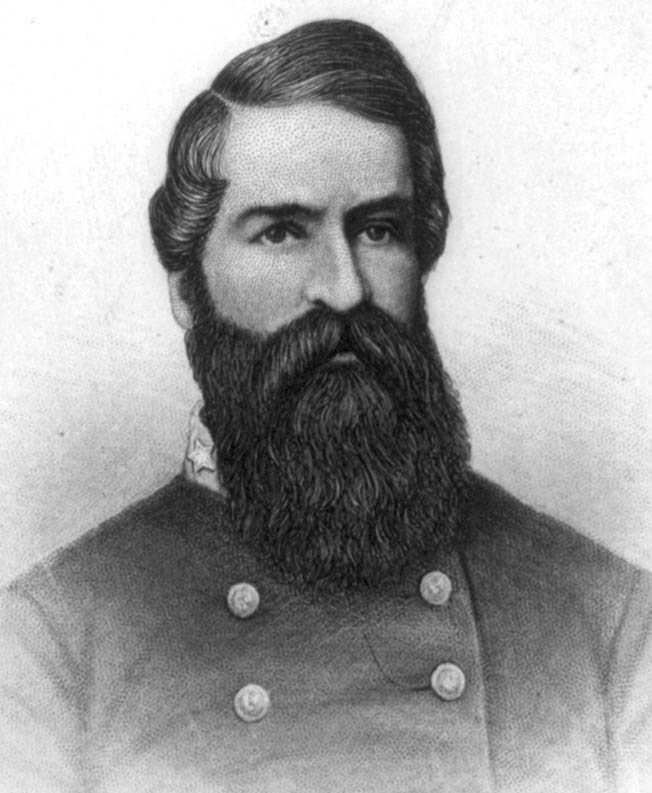

Even in an army not lacking for larger-than-life figures, Confederate cavalry leader Turner Ashby stood out from the crowd. Although not particularly tall—about five feet, 10 inches—there was something about Ashby that commanded attention. Maybe it was his dark, bushy beard, or his equally dark, ever-darting eyes.

Whatever it was, people noticed Ashby. “His face was the kind that cannot be photographed,” said his friend, Lieutenant Henry Kyd Douglas. “Riding his black stallion, he looked like a knight of the olden time, galloping over the field on his favorite war horse.” Ashby augmented his style with a battle costume that included spyglass, gauntlets, and fox-hunting horn—all the accoutrements of a Virginia-born gentleman.

As cavalry chief for the legendary Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, Ashby naturally took on some of the glamour surrounding the South’s most-vaunted warrior. Like others around Jackson, Ashby grew in stature from his close proximity to the famous Stonewall, even if the two did not always see eye to eye. The religious, liquor-abjuring Jackson frequently had to look the other way when Ashby and his looting, carousing horsemen in the 7th Virginia passed by.

Following the less than stellar Battle of Kernstown, Jackson took steps to rein in the unpredictable Ashby. Nettled by the way that Ashby had let some of his horsemen wander carelessly around Kernstown on the mistaken notion they would not be needed until the next day, Jackson divided Ashby’s regiment in half, assigning equal parts to his two infantry commanders. He intended, said Jackson, “to have the cavalry of this district more thoroughly organized, drilled and disciplined.”

Surprised and mortified by the demotion, Ashby considered challenging Jackson to a duel—only Jackson’s superior rank prevented the two headstrong men from coming to blows. Instead, Ashby announced his intention to leave the army. “This indignity,” he said, “leaves me in utter astonishment. For the last two months I have saved the Army of the Valley from being utterly destroyed.”

If Jackson thought he was merely disciplining Ashby, he was wrong. The hard-riding horsemen in his command immediately let it be known that if their longtime leader left the army, they would leave with him. It was a tribute to Ashby’s personal charisma that the notably fractious Southern cavalrymen refused to serve under anyone else.

Jackson backed down, reinstating Ashby to full command and averting a calamitous mutiny at the outset of the famous Valley Campaign. Ashby agreed to tighten his discipline, and after he was promoted to brigadier general in late May 1862, Jackson took the opportunity to urge the cavalryman to be more careful. “As it seems you are now to command a brigade,” Jackson told him, “perhaps the country may now hope for less exposure of your person.”

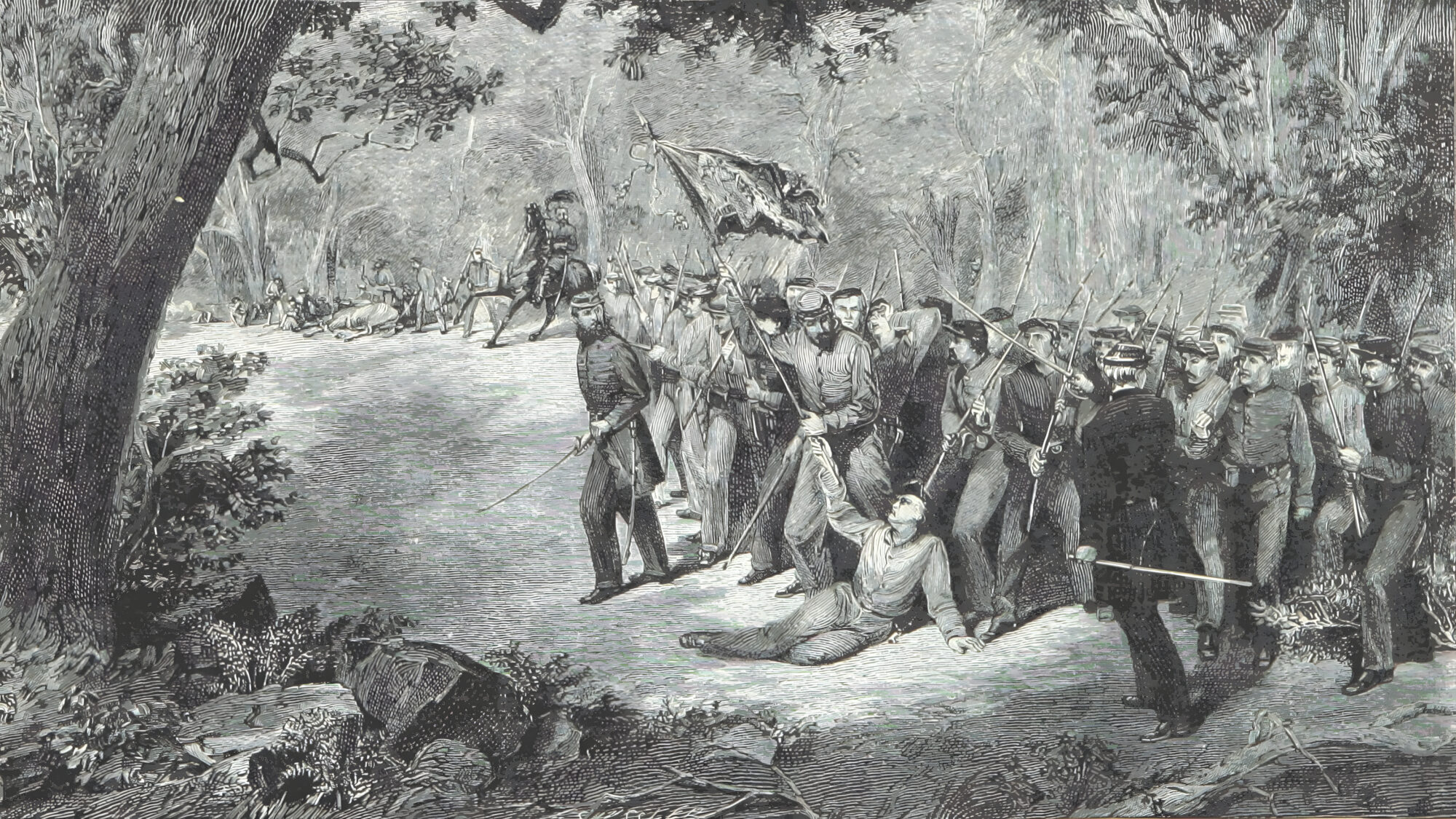

It was well-considered advice, but Ashby—as usual—did not heed it. Instead, on the afternoon of June 6, 1862, while leading a counterattack during an insignificant skirmish with Union cavalry outside Harrisonburg, Virginia, Ashby had his horse shot from under him. Dismounting, he was waving his sword and calling for his men to follow him when he was fatally struck by a bullet that passed through his right forearm and pierced his heart, killing him almost instantly.

Jackson was hit hard by his cavalry leader’s death. Before Ashby’s temporary burial at Port Republic, Jackson spent some time alone, communing with Ashby’s remains in the parlor of the Frank Kemper home in the center of the village. He left, remarked an aide, “with a solemn and elevated countenance.”

Ten months later, in a routine report, Jackson paid unusually emotional tribute to the fallen horseman. “An official report is not an appropriate place for more than a passing notice of the distinguished dead,” Jackson wrote, “but the close relationship which General Ashby bore to my command will justify me in saying that as a partisan officer I never knew his superior. His daring was proverbial. His powers of endurance incredible. His tone of character heroic, and his sagacity almost intuitive in divining the purposes of the enemy.”

Jackson might almost have been describing himself.

Roy Morris Jr.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments