By Maureen Holtz

During World War II, American women flocked to be a part of the war effort. They served as factory workers, government agency clerks, WAVES or WAACS, and artists copying propaganda posters. Many young women found that the American Red Cross offered non-nurses a unique opportunity. Jill Pitts Knappenberger was one of them.

In the fall of 1944, after two months of serving donuts, coffee, cigarettes, and Lifesavers to Allied combat troops in France’s Brest peninsula, 26-year-old American Red Cross (ARC) volunteer Jill Pitts maneuvered her 2.5-ton GMC truck, the clubmobile Cheyenne, through mud and rain to a chateau two miles southwest of Bastogne, Belgium. The journey for Jill and her crewmates, Helen Anderson and Phyllis McLaughlin—assigned to VIII Corps—ended on October 1 after four days and 600 miles traveling with a 135-vehicle military convoy.

After checking in with the 35th Special Services Division, the women started on their usual tasks, cleaning inside the truck, ensuring their supply of kerosene for their primus stove used for heating water, and making donuts for the next day using the Cheyenne’s built-in electric donut-making machine.

Nine hundred GIs awaited the Cheyenne the next day. While the built-in Victrola blasted V-disc records through loudspeakers and GIs surveyed a collection of newspapers, Jill, Helen, and Phyl heated water for the 50-cup coffee urns and served the snacks. The Cheyenne’s state register—a large bound book with the states listed in alphabetical order for troops to inscribe their names, hometowns, and divisions—enabled the GIs to locate familiar names. The troops were grateful that General Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander of Allied forces in Europe, directed the ARC to send clubmobiles packed with food and pretty young women to the European Theater soon after D-Day.

The wet 1944 autumn posed problems at mealtime. The women ate quickly to avoid rain overflowing their mess kits. On November 20, Jill, Phyl, and Helen moved on to a small town and apartment 15 miles from Bastogne. They ate in a mess hall for the first time since July 31, when Jill piloted the Cheyenne off an LST (Landing Ship, Tank) onto Utah Beach in Normandy in complete darkness. The apartment still had furniture, electricity, a back balcony, and a bathtub, a welcome relief after 15 weeks with only two hot showers. For humor, Jill hung a framed and autographed oil painting of Hitler that a colonel had given her.

On December 5, 1944, James L. Brown, director of the Clubmobile Department, sent the women a memo with General George S. Patton, Jr.’s comments about the ARC’s work with the Third Army: “In my opinion the Clubmobile Girls of the American Red Cross have performed and are performing a very major work in maintaining the morale of the frontline troops and in keeping before the eyes of our soldiers the best traditions of American womanhood. The Third Army joins me in a respectful and enthusiastic endorsement of the American Red Cross.”

On December 11, Jill learned that her twin brother Jack, Captain John Joseph Pitts III, commander of Battery A, 590th Field Artillery, 106th Infantry Division, was stationed near St. Vith, 30 miles north of Bastogne. The Cheyenne was scheduled to join the 106th in a few days. Although artillery fire periodically punctuated the winter quiet, the Army considered St. Vith’s wooded, hilly terrain unsuitable for large-scale attack, deeming it safe for the women.

Jill arranged a three-day leave to surprise her brother. Born in Evanston, Illinois, only a few minutes after Jack, Margaret Frances was nicknamed “Jill” because of the nursery rhyme, “tumbling after” Jack, as her parents told her.

On December 12, with ARC field director Brad Carroll managing the frigid white-knuckle drive to St. Vith across the Schnee Eifel ridge, Jill reached division headquarters, where she was directed 10 miles east to Jack’s battalion headquarters in Schönberg, Germany. Jack’s commanding officer, Major Tetsey, called Jack in nearby Radscheid and ordered him to the post, not giving any reason.

While waiting, Jill lunched with Tetsey and battalion commander Lt. Col. Vanden Lackey before rummaging through an abandoned warehouse containing liberated fabric. Thrilled at seeing Jill, Jack drove her to his battery and introduced her to the cooks, the men on the guns, his top sergeant, and the supply sergeant who gave her saddle soap for her shoes.

Jill spied the enemy several hundred yards away on a hill. When she asked where the Allied troops were, Jack pointed out a platoon behind them on the right and another on the left. The Army had not felt the need to space the men across the usual three-mile front, instead stretching the troops across 27 miles.

The twins spent the rest of the evening around a stove fire, talking into the night about what they had both encountered since parting 18 months earlier. Jill was glad to have joined the Red Cross. WAVES and WAACS weren’t guaranteed overseas assignments, but clubmobile volunteers were. In Europe she was part of the action.

In 1942, the ARC Commissioner for Great Britain and Europe, Harvey D. Gibson, devised the clubmobile plan to bring a taste of home to combat troops. The first clubmobiles appeared in England. Englishmen unable to serve otherwise drove the Greenline buses, remodeled with kitchens and a lounge. Some vehicles, outfitted with movie projectors, became “cinemobiles.” All were staffed with women between the ages of 25 and 35 with some college education. The clubmobiles, named after United States cities and states, were arranged into 10 groups, each denoted by a letter of the alphabet. The 32 women in each group were expected to serve for the duration plus six months. The Cheyenne belonged to Group F.

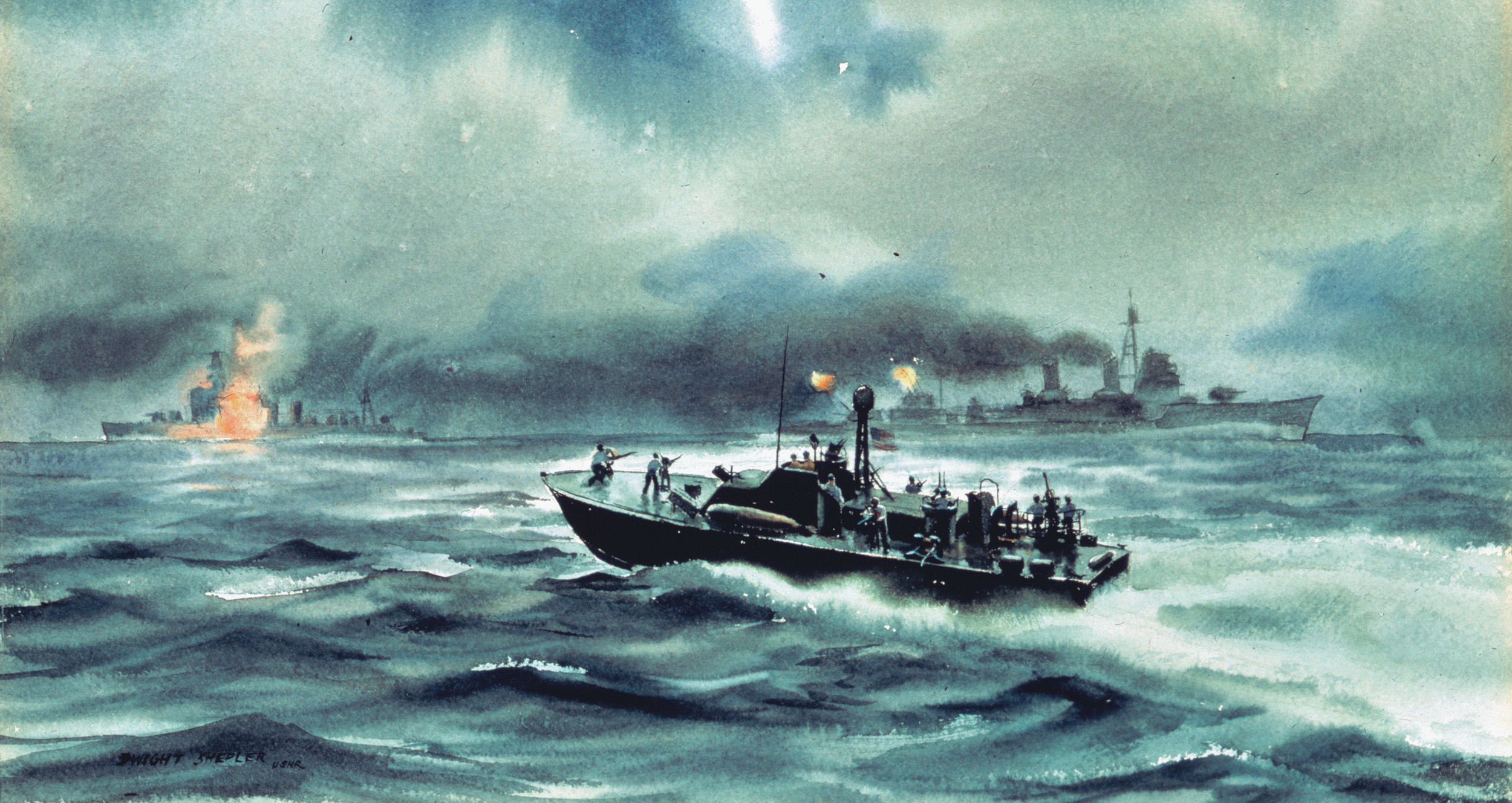

A year earlier, around Christmas 1943, Jill was part of the largest convoy of aircraft carriers, battleships, troop ships, and submarine chasers crossing the Atlantic. Soon after docking aboard the transport ship Brazil in Scotland, she arrived in London at 2 amin the middle of an air raid. The V-1 flying bombs, also known as doodle-bugs or buzz-bombs, made her jittery. Jill would wait for 60 seconds after the motor turned off and wonder where the bomb would explode.

Mobilization for D-Day required clubmobile women picked for Europe to drive 2.5-ton GMC trucks—smaller and easier to manage than Greenline buses. Jill and her crewmates took a 10-day, 500-mile obstacle driving course, learning truck maintenance and how to change the 55-pound tires. Jill taught new volunteers how to drive Jeeps and trucks, including clubmobiles, almost 100 of which were used in the European Theater.

Jill snapped photographs of Jack that night in Radscheid with plans to send the prints to their parents in Illinois. She and Jack agreed to meet up on December 16, in St. Vith to celebrate Helen’s birthday, and again on Christmas.

On December 13, Jill headed back to Bastogne. During the next two days, the women cranked out donuts for 1,000 men. Jill tried to cable her parents about seeing Jack, but due to the season’s mail rush the Army banned cables from December 6 until after Christmas. Jill took her camera film to Special Services to develop her photographs and forward them to her.

The women left the area they called “Mud Flats” on Saturday, December 16. Before heading to their three-week assignment in St. Vith, Jill and her crewmates lunched in Bastogne at rear corps headquarters with Colonel C.B. Warden and intelligence officer Lt. Col. Kenny Clark.

Jill’s 30-mile trek to Vielsalm took three hours. In shops there, they purchased Christmas decorations and presents for Helen’s party, meeting several GIs who warned the women to buy candles. A counterattack had started that morning, and German artillery had knocked out the electrical plant in St. Vith, 11 miles east. Jill finally rolled the Cheyenne into camp on the snowy western edge of St. Vith. GIs clustered around the truck, stunned that the crew made the trip with the enemy only a few miles away.

The women stashed their belongings in quarters inside the dispensary. Jill mentioned several times needing to call Jack. Officers persuaded her to eat first. After dinner, Lt. Col. Veazie, a chaplain, pulled the women aside and broke terrible news. Jack had been killed that afternoon while helping his men at a forward gun position. A German 88mm shell fragment had pierced his helmet and skull, instantly killing him.

The officers and her crewmates accompanied Jill back to her quarters, where a medic ordered sleeping tablets for her. When Jill woke the next day, still absorbing the horrific news of Jack’s death, she learned she could not tell her parents about it until 30 days had elapsed. It was the Army’s job to relay the sad news. Jill could mention seeing Jack, but nothing more. She fired off a letter immediately to her family and pretended to be cheerful, writing only about visiting with Jack and, as a hint, to remember the 16th.

Jill joined her crewmates serving coffee, gum, and cigarettes—no donuts due to lack of electricity. The women also served hot soup to the shell-shocked and wounded men brought to the dispensary. Jill held the hand of a soldier while a surgeon pulled shrapnel out of his other arm.

The roads jammed with vehicles of all kinds—armored cars, tanks, half-tracks, trucks—all hurrying back and forth to the front. A tank battle raged in town. Snow and freezing fog grounded the air force while fighting escalated in and around St. Vith, a crucial hub of six paved roads. GIs took German parachutists as prisoners, but by the night of the 17th, the Germans had surrounded the area. The Battle of the Bulge was in full swing.

Jill recalled the London air raids. At least there she could escape into the Underground’s bomb shelters. In St. Vith, she felt like a sitting target. “We were concerned what would happen if we were captured. Would they respect us as young women or take advantage of us? But you adjust to combat,” said Jill. She carried a Certificate of Identity of Non-Combatant noting that, if captured, she should be afforded the same privileges as a captain.

St. Vith residents griped about being caught in the middle of the fighting. Food supplies dwindled. Everyone functioned on half rations. The women gave all remaining provisions—coffee, sugar, flour—to add to the Army’s supplies. Over the next several days, the women cleaned, mended clothes, nursed, and tried to cheer the GIs. The women prayed for clear weather to enable aircraft to drop food and support.

Word spread of the atrocities committed on December 17 at Malmedy when Germans slaughtered 84 American POWs in a field. Other regiments were cut off without food, water, or ammunition. Surrounded, Jack’s battery, along with the 423rd Infantry Regiment, surrendered on December 19. That same day, Jill and her crewmates were told to pack up their musettes—their shoulder bags—with whatever the women wanted most to keep and be ready to move at a moment’s notice. The women broke into their Christmas packages, pulling out food and luxuries such as nylons and perfume.

The front lines were now only a mile away. Tanks rumbled by. A soldier gave Jill an incendiary bomb which she hid in the Cheyenne, not planning to leave anything behind for the Germans.

During the afternoon of Friday, December 22, the 82nd Airborne Division cleared a road to the northwest. It might be open for only a few hours, the women were told. GIs placed the Cheyenne in the first group to escape. After removing the bomb from the truck, Jill pulled into line behind an Army Jeep and its quarter-ton trailer. An armed escort followed the Cheyenne. Trying to ignore the incoming artillery fire and grateful for Allied counterfire, Jill’s convoy moved out at 3 pminto the swirling snowstorm toward VIII Corps forward headquarters.

Jill drove the Cheyenne past the site of the Malmedy massacre, where the GIs’ bodies still lay. Some hours later, the tail lights of the leading vehicle disappeared. Unable to hear anything due to artillery fire, Jill pulled the Cheyenne to the side of the road. The women ran ahead. The Jeep had collided head-on with an ammunition truck. Two of the Jeep’s men were hurt.

Along with two other Jeep passengers, they pushed the vehicle into the ditch to allow the convoy to pass. The women packed an injured lieutenant colonel into the Cheyenne’s cab with Jill and Helen. The other men grabbed luggage and equipment and climbed in back with Phyllis. According to the Geneva Convention, armed guards were not allowed inside the clubmobile, but this was an emergency.

Jill and Helen hitched the Jeep’s trailer to the Cheyenne. Jill drove onward searching for the men’s VIII Corps unit, finally stopping at a forward compound where a nearby hospital could attend to the lieutenant colonel. Informed that a tank battle was in progress ahead, the women stayed overnight. An officer woke the women at 7 amand told them to leave immediately. The Germans had breached an important roadblock during the night.

Jill headed northwest toward Namur. Thousands of civilians crowded the roads, fleeing the Germans. The crowds and destruction made driving difficult. At one point, Jill detoured 16 miles because of a knocked-out bridge. Eventually, the crew obtained directions and a map. At 6 pmon Saturday, December 23, Jill dropped the men at VIII Corps forward headquarters at Florenville, Luxembourg. Army personnel arranged for the women to stay in a house recently vacated by Collier’s reporter Ernest Hemingway.

Jill drove 30 more miles the next day, Christmas Eve, arriving around lunchtime at Charleville-Mézières, France, where the other Group F crews hunkered in unheated and windowless barracks. After the Cheyenne crew freshened up, Group F gathered for a potluck Christmas celebration of goodies from home, along with liberated alcohol. A bomb dropped nearby, shaking the building and momentarily disrupting the Christmas carols.

Later, Jill was dismayed to learn the photographs of Jack from the film she expected to be developed were accidentally forwarded on to an unknown person. There would be no last photograph of Jack to console the Pitts family.

The Cheyenne was one of the first clubmobiles to move on after the Battle of the Bulge. During the second week of January, Jill drove back to the Bastogne outskirts, where the women established themselves in bullet-riddled French-Belgian barracks. With mud causing almost impossible driving conditions, the Cheyenne crew joined the Miami’s crew to run a donut dugout at VIII Corps headquarters.

Once while serving the GIs, Jill accepted a tank driver’s offer to drive his Sherman tank. Jill drove it in a circle on a parade ground in the middle of Bastogne. Sometimes the GIs would let the women pull the lanyard on the artillery guns.

In March, while on detached service with the 76th Infantry Division, Jill drove the Cheyenne over a pontoon bridge across the Moselle River, then across the Rhine. An American soldier gave her a camera and film he confiscated from a German soldier. Jill used that camera through the rest of her service in Europe.

The Cheyenne followed VIII Corps to Eisenach, Germany, on April 10, 1945. Two days later, the same day that 12th Army Group commander General Omar Bradley and General Eisenhower visited, the women accompanied the 1107th Engineer Combat Group into Ohrdruf, the first liberated concentration camp. Partially burned bodies still lay in the crematorium. The women visited Buchenwald the day after its liberation. Nothing had prepared Jill for the grisly lampshades made from human skin that had been made for the camp commandant’s wife. Tattooed skin was particularly prized.

Later in April, GIs escorted Jill, Helen, and Phyl for a long distance into the Merkers salt mines. “The soldiers took us into the mine. It was like going into a cave about six miles deep. We saw piles of gold, bags and bags of money, and artwork everywhere.”

After reaching Hitler’s Bavarian retreat, a friend photographed Jill sitting at Hitler’s Berchtesgaden conference table. On May 8, the women celebrated VE-Day in Altenburg, Germany, with the 6th Armored Division. After signing their names on two Nazi flags, they applauded the removal of their truck’s headlight covers.

Jill’s last assignments after VE-Day were at clearing camps for evacuating troops. She operated a clubmobile group near Châlons-en-Champagne, France, billeting with the Mauguère family in their hunting lodge. The only French Jill had known before reaching France was “Chevrolet coupé,” so while Jill taught the family English, they reciprocated with French. Jill joined the family dining outside on long tables with 15 or 20 people during the lengthy summer days. The family knew how to relax, drinking wine like Americans drink water. One evening, Monsieur Mauguère’s nephews put 12 shot glasses out with different liquids in them —wine, liqueur, and cognac. There was no identification on the glasses. Monsieur correctly guessed all of the liquids.

After six weeks with the Mauguères, Jill was ordered to Camp Philip Morris, one of the embarkation camps for soldiers awaiting transportation home and discharge. In mid-August, Jill learned her father was sick. She returned home on the passenger ship John Ericssonas. Jill earned a European Theater of Operations ribbon with five stars, one for each of the battles of Brest, Normandy, the Bulge, Germany, and the crossing of the Rhine.

During World War II, approximately 1,000 young, energetic women volunteered for clubmobile work serving combat troops. Today, only a handful, including Jill, remain. She still sparkles whenever she speaks about her favorite subject, American GIs.

Senator Susan Collins (R-ME) said it best in 2012 when honoring the ARC clubmobile women: “A visit from a clubmobile was one of the most significant events for a young G.I. in combat far from home, and the women of the clubmobiles, young women from every single state, acted as friends and sisters to the troops with whom they interacted.”

Maureen Holtz is a first time contributor to WWII History. She writes from her home in Champaign, Illinois.

While visiting the American Cemetery at Omaha Beach I gained fresh appreciation for the support American women gave to the war effort. 2 million men in France in 44. 3.4 in the South Pacific… who kept the home fires burning? ‘Manned’ the factories?

My mom became a widow with 2 small children. Captain Hank Warfel buried St.Lo cemetery

My father served in WWI in the Army and lied about his age to serve in WWII as a Navy Seabee. He related stories of these tireless women who supported the war efforts as mechanics, nurses, secretaries and at home as factory workers.

In 1948 women became a permanent part of the Armed Forces. Recognition is long overdue.

What an amazing story!!! I’m a retired HS History teacher (MA in History, Specialist degree in Ed and a German History minor). I taught at Villa Grove HS for 35 years before retiring. Just wanted to share how much I loved reading this. Would love to meet you sometime; however, I’m living in Macon, GA at the moment.

I looked at my Clubmobile article today to send to someone and saw your comment from December. It was very nice of you to write such lovely things. I appreciate your kind words. Best wishes. History is always so fascinating, isn’t it? It was my 2nd major and I taught HS briefly myself.

Ann,

I was a Donut Dollie in Vietnam. The 80 th anniversary of D Day is coming up next year and we are trying to help Overland Tours get a museum for the Clubmobile Girls set up in Normandy.

Also, I live in Macon.

I am on Facebook

Dorner Carmichael