By James M. Powels

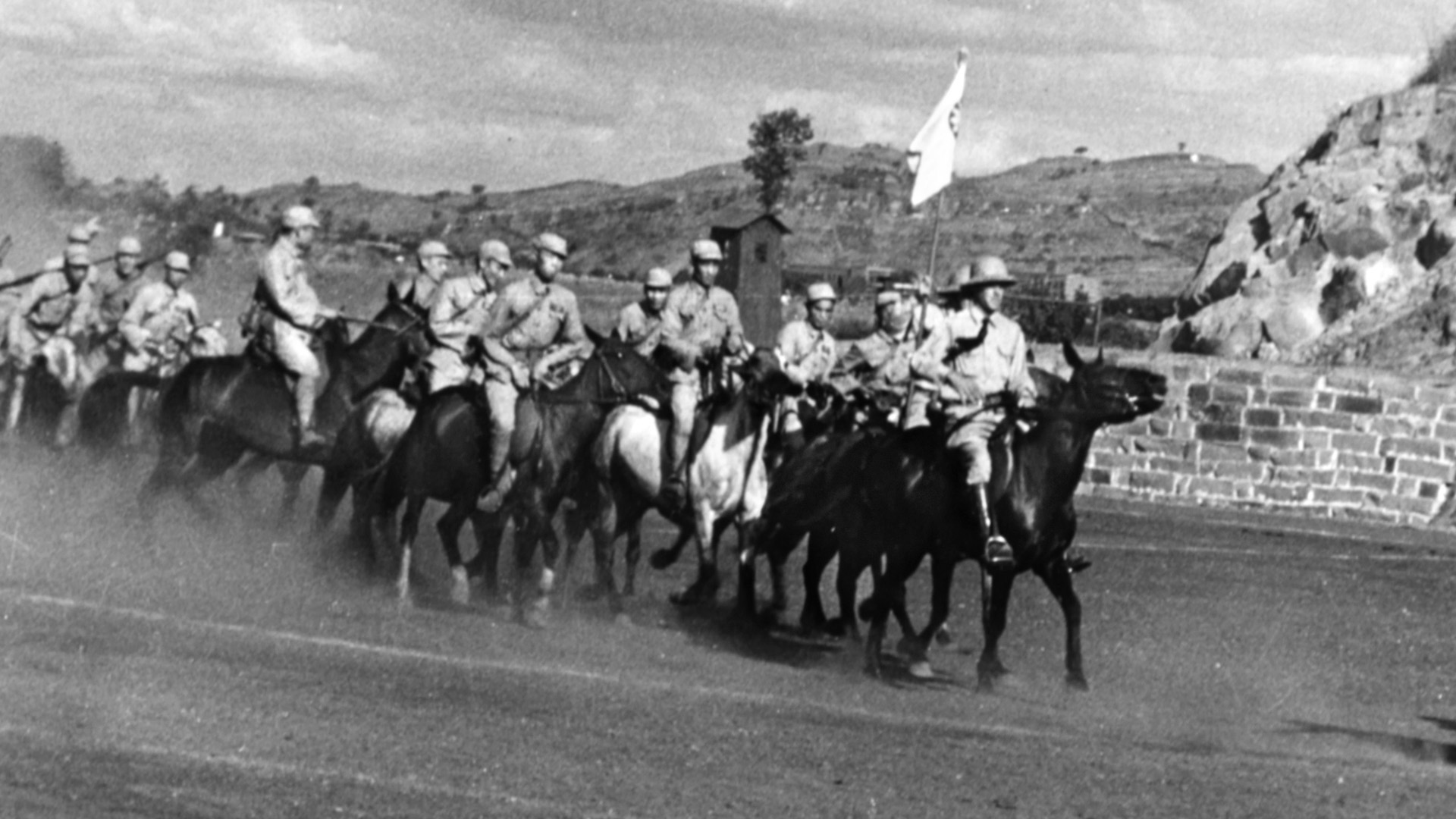

One of the primary reasons given for the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run was the lack of adequate cavalry. In response, Secretary of War Simon Cameron granted permission to prominent men in various Northern states to raise three-year cavalry regiments. One of these men was 67-year-old William Halsted of Trenton, New Jersey, an eminent state politician, former congressman and lawyer. Since the State of New Jersey was authorized by the Federal government to raise only infantry regiments and there was no organized cavalry in the state militia, Halsted raised his cavalry regiment as an independent unit under orders from the War Department. Halsted began recruiting for his regiment, called Halsted’s Horse, in August 1861. He had no trouble filling his ranks, and by August 24 the first four companies had arrived in Washington, followed a week later by the remaining six companies. In February the regiment was accepted into Federal service as the 1st New Jersey Cavalry.

When President Abraham Lincoln issued his call for volunteers on April 15, 1861, Sawyer answered the call that very day, being the first in the county to volunteer. Since there were no military units in the state ready to accept volunteers, he went to Trenton and offered his services to New Jersey Governor Charles Olden, who sent him to Washington with important dispatches for the secretary of war. A few days after arriving in Washington, Sawyer joined a paramilitary unit raised to guard the city. Shortly after that he enlisted in the Allentown Rifles, one of the first Pennsylvania volunteer companies sent to protect the city.

Wounded at the Battle Of Brandy Station

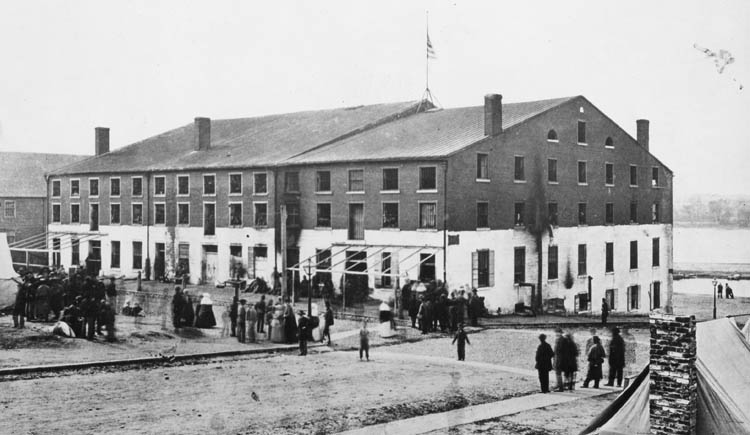

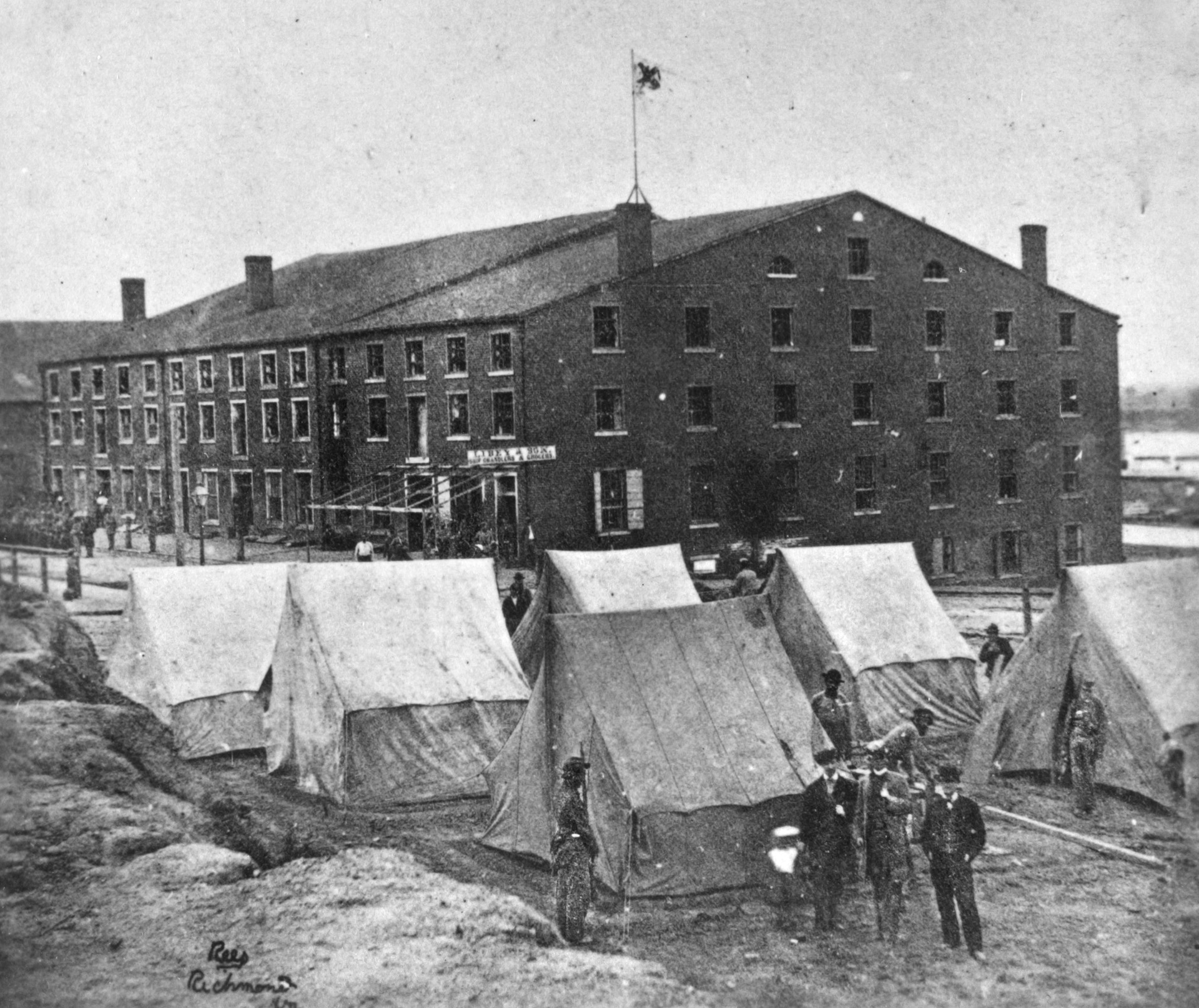

On June 9, 1863, at Brandy Station, Virginia, the 1st New Jersey Cavalry fought one of its fiercest and finest engagements of the war when a force of Union cavalrymen supported by infantry and artillery made an early morning attack on the encamped Confederate horsemen of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. The 1st New Jersey, under Lt. Col. Virgil Broderick, was in the forefront of the action, making charge after charge into the Confederate ranks. Near the end of the battle, Sawyer was shot in the neck and thigh. Severely wounded, he was left for dead. However, he survived his wounds and was sent to Richmond, Virginia, where he was confined in Libby Prison.

On June 9, 1863, at Brandy Station, Virginia, the 1st New Jersey Cavalry fought one of its fiercest and finest engagements of the war when a force of Union cavalrymen supported by infantry and artillery made an early morning attack on the encamped Confederate horsemen of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. The 1st New Jersey, under Lt. Col. Virgil Broderick, was in the forefront of the action, making charge after charge into the Confederate ranks. Near the end of the battle, Sawyer was shot in the neck and thigh. Severely wounded, he was left for dead. However, he survived his wounds and was sent to Richmond, Virginia, where he was confined in Libby Prison.

Arriving at Libby, Sawyer expected to be treated like any other Union officer and hoped to be exchanged soon. However, this was not to be his lot. Sawyer and another officer soon found themselves pawns in a lethal tit-for-tat game between the Federal and Confederate governments that would make headlines in both the North and South. Sawyer’s ordeal had begun back in April when Confederate Captains William F. Corbin and T.G. McGraw were arrested near Rouse’s Mills, Kentucky, for “recruiting men within the lines of the U.S. forces for the so-called Confederate Army.” Corbin was also charged with “being the carrier of mails, communications and information from within our [Union] lines to persons in arms against the Government.”

On April 22, 1863, by order of Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, commander of the Department of the Ohio, the two men were tried as spies before a military commission in Cincinnati. Corbin and McGraw were found guilty by the court and sentenced to death. The sentence was approved by Burnside and President Lincoln, and the pair was taken to the prisoner of war camp on Johnson’s Island, where on May 15 they were executed by firing squad.

The Lottery of Death Commences

Confederate authorities reacted swiftly after learning of the deaths of Corbin and McGraw from Northern newspapers. Considering the victims to have been duly authorized by the Confederate Army to recruit in Kentucky and not spies working as recruiters, the Confederate government ordered that “two captains now in our custody shall be selected for execution in retaliation for this gross barbarity.” Three days later the Federal government upped the ante when Lt. Col. William Ludlow, agent of prisoner exchange for the Union, responded “that for each officer so executed one of your officers in our hands will immediately be put to death and if this number be not sufficient it will be increased.” Thus began a series of events that had the potential of turning the war into a vicious conflict of retaliation.

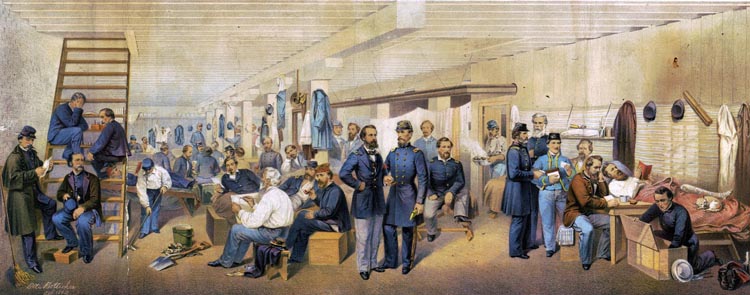

In Libby Prison on the morning of July 6, 74 Union prisoners with the rank of captain, including Sawyer, were assembled in a room of the prison. Expecting to be paroled, the officers were shocked to learn that two of them were to be selected by lot to be executed in retaliation for the deaths of two Confederate officers shot for being spies in Kentucky. When the question came up of who was to draw the names, Sawyer suggested that one of the prison chaplains be appointed. The Reverend Joseph P. Brown of the 6th Maryland reluctantly accepted the unenviable task. The first name he drew was Sawyer’s, and the second was Captain John M. Flinn of Company F, 51st Indiana Volunteers. “When the names were read out,” the Richmond Dispatch reported, “Sawyer heard it with no apparent emotion, remarking that someone had to be drawn, and he could stand it as well as anyone else. Flinn was very white and much depressed.”

Sawyer and Flinn were granted permission to write letters to their families. However, before either man had finished his letter they were put in a cart and made their way through the streets of Richmond toward the gallows under cavalry escort. Sawyer later recalled, “We had almost reached the city limits when we met a prominent Roman Catholic bishop, who stopped to enquire of the Confederate officer about us. Captain Flinn, who was a Catholic, said he was being executed without the ‘rites of clergy.’” The bishop, who was a friend of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, interceded on Flinn’s behalf and secured a 10-day stay of execution for him and Sawyer.

The “Lottery” Gains National Attention

Sawyer finished a letter to his wife upon his return to the prison. After finishing the letter, Sawyer related, “We were taken to the cellar and placed in a dungeon, and isolated from the world and our companions; and the only company we now had were the rats and the vermin, which swarmed over us in great numbers.”

Immediately upon receiving the letter, Mrs. Sawyer brought the matter to the attention of influential friends and the press. The letter had the effect Sawyer had hoped, and his predicament became public knowledge. As a result, on July 15, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck wrote to Ludlow: “The President directs that you immediately place General W.H.F. Lee and another officer selected by you in close confinement [and to] be immediately hung in retaliation” if Sawyer and Flinn were executed. Furthermore, Ludlow was instructed to notify the Confederate government of the decision.

Sawyer and his companion were fortunate that at the time the Federal government held as a prisoner of war Brig. Gen. William Henry Fitzhugh Lee, the second son of Robert E. Lee. Rooney Lee, like Sawyer, had been wounded at the Battle of Brandy Station but was not captured until almost two weeks later while recuperating at the home of one of his wife’s relatives near Hanover, Virginia. The other officer selected for retaliation was Captain Robert H. Tyler of the 8th Virginia Infantry, who was a prisoner in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington. Lee was held as hostage for Sawyer and Tyler for Flinn.

As the story of Sawyer and Flinn unfolded, newspapers on both sides fed the furor over their fate and the possibility of retaliation. Ignoring the fact that a son of General Lee and another officer were being held for retaliation, the Richmond newspapers continued to clamor for the execution of Sawyer and Flinn, while newspapers in the North debated whether the death sentence would be carried out. In the meantime, Sawyer and Flinn were released from their underground cells and received the same treatment as the other Union officers in the prison. Despite their rhetoric, the Richmond newspapers wrote of Sawyer’s courage and his stated determination “that New Jersey should have no cause to be ashamed of his conduct.”

Cooler Heads Finally Prevail

Both sides now found themselves in a sticky situation. If Sawyer and Flinn were executed and Lee and Tyler killed in return, what would stop the South from executing two or more prisoners in retaliation for Lee and Tyler. The whole affair could easily spiral out of control, resulting in the mass execution of prisoners of war. Fortunately for all concerned, cooler heads prevailed and through quiet negotiations an exchange of the doomed men was arranged. In March 1864, Sawyer was exchanged for Tyler and Flinn for another Confederate captain, while Lee was exchanged for Brig. Gen. Neal Dow of Maine. Sawyer’s nine-month ordeal was finally over.

Sawyer returned to Cape May, where he became the proprietor of the Ocean House, one of the town’s largest hotels. In 1875 he built a boarding house nearby and developed it into one of Cape May’s finest resorts, the Chalfonte Hotel, which is still in business today. All told, he was involved in some 10 hotels in three states. He also held various local, state, and federal government jobs, was a successful real estate investor, and gave a popular lecture on his military career and the “Lottery of Death.” After his first wife died, he married a much younger woman and had two more children. He died on October 16, 1893, in Cape May. His obituary read: “Captain Sawyer fought in the war of the rebellion, and was recognized as one of the bravest soldiers that ever entered a battle. One of the most stirring incidents of his life, and one which the Colonel loved to talk about, was his capture and confinement in Libby Prison, and his subsequent sentence to be shot to death, he having been the unfortunate victim of the drawing in the ‘Lottery of Death.’” Henry Sawyer had cheated death for nearly 30 years.

Interesting story. As you wrote, “cooler heads prevailed” instead of endless retaliation.