By David A. Norris

With freshly honed sabers, more than 2,000 Union cavalrymen rode toward the Confederate-held Rappahannock River crossing of Kelly’s Ford in March 1863 with orders to attack and rout or destroy Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee’s Rebel cavalry. With them, the bluecoats carried a day’s forage, rations for four days, and a sack of coffee for a particular Confederate general.

One of the South’s advantages offsetting the North’s superiority in military and industrial resources was the Confederate cavalry. Led by bold and talented commanders, such as Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown Stuart, the Rebel cavalry in Virginia completed one spectacular raid or expedition after another, while Union cavalry commanders blundered about with little success in stopping them.

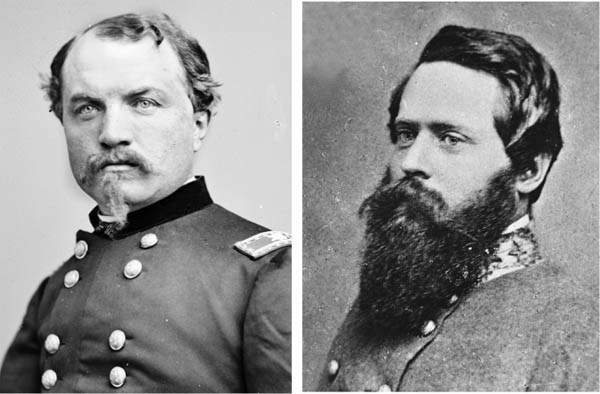

Major General Fitzhugh Lee, a nephew of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, led a reconnaissance of the enemy lines from February 24 to February 26. His troopers struck a Union force at Hartwood Church in Stafford County, northwest of Fredericksburg, on February 25. Eluding pursuit, Lee’s men crossed the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford on February 26, bringing back more than 150 prisoners. Thirty-six Union soldiers were killed in the action. Lee’s total casualties were just 14 killed, wounded, or missing.

Most of the Union casualties belonged to Union Brig. Gen. William W. Averell’s 2nd Division of the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Lieutenant Charles Palmore, an antebellum physician who served during the war as a line officer in the 3rd Virginia Cavalry, had stayed behind at Hartwood Church with some wounded Confederates. Lee left Palmore a note to give to Averell. Lee and Averell were old friends from their days at West Point in the 1850s, but the war turned their friendship into rivalry. “I wish you would put up your sword, leave my state, and go home,” Lee wrote. “You ride a good horse, I ride a better one. Yours can beat mine at running. If you won’t go home, return my visit, and bring me a sack of coffee.”

The Hartwood Church clash was only one, and by no means the least, of a long string of defeats suffered by the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac. The fairly minor raid infuriated Maj. Gen.

Joseph Hooker, who had replaced Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside as the commander of the Army of the Potomac on January 26, 1863, in the wake of the Union defeat at Fredericksburg.

Hooker sought to surprise the Rebels with a major raid of his own making. It was well known to the Union that Fitz Lee’s Second Brigade was camped near Culpeper Courthouse. Hooker ordered a large-scale reconnaissance of the fords on the Rappahannock River where a Union force might cross to assail Lee.

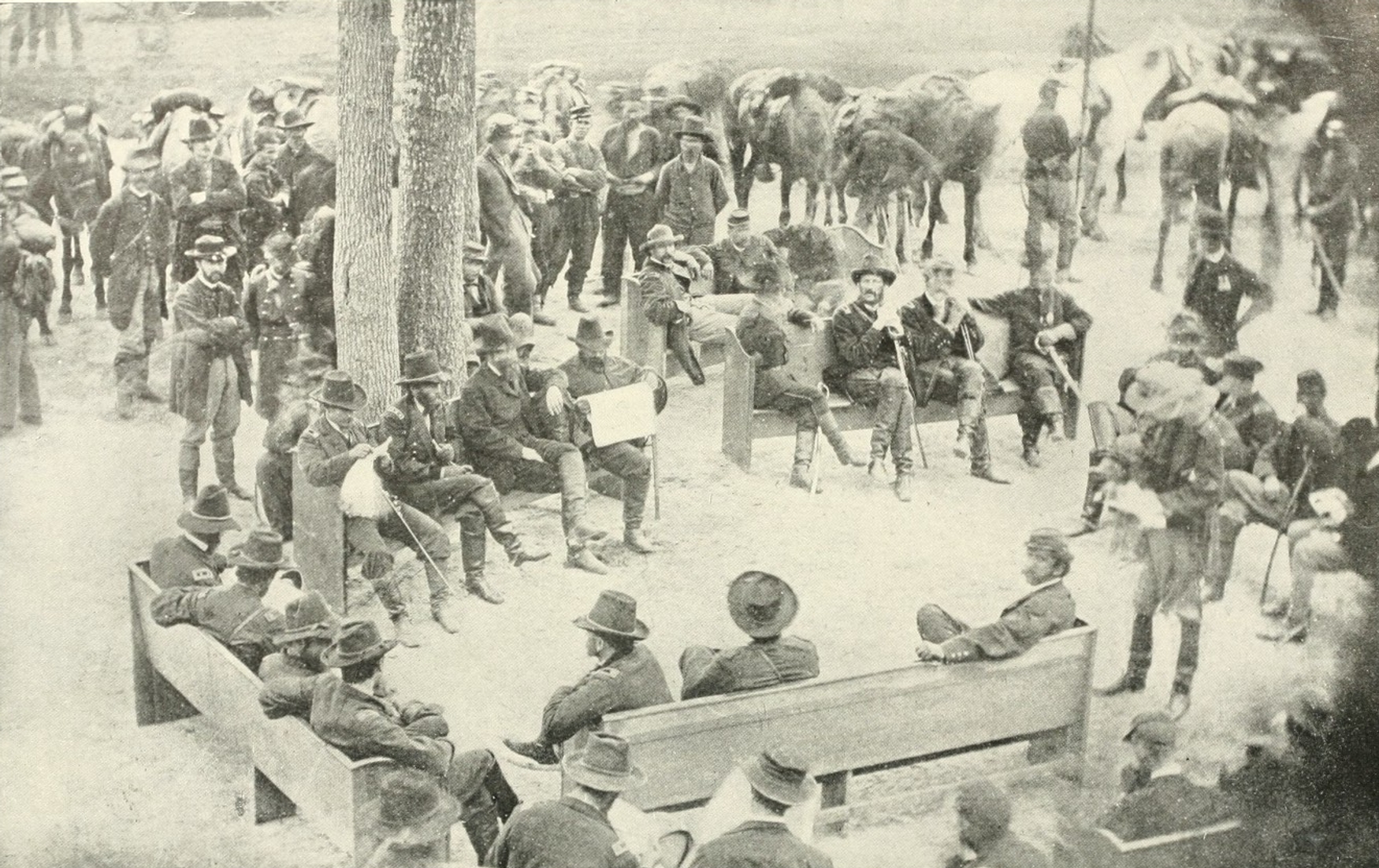

Hooker planned to launch his attack on March 16. He assigned 3,000 men and six guns to Brig. Gen. William W. Averell. Twenty-nine year-old Averell, who hailed from upstate New York, had graduated in the bottom third of the West Point Class of 1855. After brief assignments in Missouri and Pennsylvania, 2nd Lt. Averell served in New Mexico from 1857 to 1859 where he fought in skirmishes against the Kiowa and Navajo. Having suffered a severe wound in 1859, he took an extended leave of absence to recover. He was commissioned as colonel of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry on August 23, 1861, and received his promotion to brigadier general on September 26, 1862. On February 22, 1863, Averell was given command of the 2nd Cavalry Division.

Hooker instructed Averell to take every precaution necessary to ensure the operation’s success. Averell was to attack and break up the enemy cavalry camp at Culpeper Courthouse. As a precaution, Averell wanted another cavalry regiment sent to Catlett’s Station to cover the middle fords of the Rappahannock. From there pickets could watch for enemy forces approaching from Warrenton, Greenwich, and Brentsville. Averell’s superiors deemed this request unnecessary, and no additional men were provided. Averell decided on his own to detach 900 sabers (1st Massachusetts Cavalry and part of the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry) to guard Catlett’s Station, cutting his expeditionary force by almost one third.

Sending the troopers to Catlett’s Station left Averell with 2,100 men. Colonel Alfred Duffie’s 775-man brigade included the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry, the 4th New York Cavalry, and the 6th Ohio Cavalry. Colonel John B. McIntosh commanded a total of 565 men in the 3rd, 4th, and 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Two regular army regiments, the 1st U.S. Cavalry and the 5th U.S. Cavalry, rounded out the force with 760 men.

Following orders from Hooker, Averell left camp on March 16. Captain George Bliss of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry noted that his men moved out about 8 am, carrying four days’ rations and one day’s forage. They rode for 16 miles, halting at dusk at Morrisville. Their camp was about four miles east of Kelly’s Ford.

Lieutenant George Browne commanded the 6th New York Battery, the artillery unit assigned to Averell. With its half-dozen rifled guns, the 6th New York Battery left its camp at Aquia Creek at dawn on March 16. But a guide took them down the wrong road, causing such a delay that they did not catch up with the cavalry at Morrisville until 11 pm. After their long day’s travel, which would have been more than 20 miles even without a wrong turn, the horses were in poor condition, noted Averell.

About 5 amon March 17, Averell’s advance reached Kelly’s Ford. Twenty-five miles upstream from Fredericksburg, Kelly’s Ford was an often-used Rappahannock River crossing. The ford got its name from John Kelly, a Culpeper County businessman who owned a sprawling mill complex on the south bank of the river. Clustered around the mill were homes that made up the village of Kellysville.

Averell’s advance met Captain William F. Hart of the 4th New York Cavalry with about 100 men of his regiment and the 5th U.S. Cavalry. Hart was ordered earlier to take a position near the ford and seize it at first light. But Hart’s task was not to be as easy as that.

A telegram from the headquarters of the Army of Northern Virginia, warning of Averell’s approach, had reached Fitzhugh Lee at 11 amthe previous day. That evening, Confederate scouts observed the Union cavalry had reached Morrisville and made camp. To slow down the enemy’s crossing, the Rebels cut trees down to block the ford and constructed abatis on both banks of the river.

Lee considered that the Yankees had two choices for a Rappahannock crossing: Kelly’s Ford and the Orange & Alexandria Railroad Bridge, which was situated four miles above the ford. Lee sent 40 men to bolster a 20-man picket station at Kelly’s Ford. Commanded by Captain James Breckinridge of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry, the pickets were deployed in rifle pits and a dry mill race that served as a ready-made trench.

When the rest of Averell’s men reached Kelly’s Ford, it was still in Rebel hands. The obstructions at the crossing were piled so high that, as a Rhode Island regimental historian put it, “but one horse could leap them at a time, and that at extreme difficulty.” That morning, the ford was about 100 yards wide and as much as four feet five inches deep, which was about the maximum depth military manuals recommended for a successful crossing of cavalry. March 1863 had been raw and bitter in central Virginia, and the Rappahannock was icy cold. Hart’s men had found good cover in an empty canal that paralleled the river. They exchanged fire with the Confederates but were unable to push across the river.

Breckinridge was down to only about 15 men. As was customary, he had sent one out of four of his men to the rear as horse holders. It was in this depleted condition that the Confederates received the first enemy charge. As for his 40 reinforcements, they had been deployed too far in the rear to reach the ford in time to repel the first enemy charges.

While Averell looked for a better crossing, his chief of staff, Major Samuel E. Chamberlain, gathered Hart’s men and more of the 4th New York Cavalry. Covered by firing from the canal bed, Chamberlain led his men in column of fours to the ford. At the river’s edge, the abatis formed an impenetrable barrier in the face of the enemy. Chamberlain’s attack withered away as the men retreated back from the river.

Union troops inspected another potential crossing a few hundred yards away but found that steep banks and deep water made fording impossible. Wheatley’s Ford, a short distance upstream, was also impassible. Kelly’s Ford was the only place within reach to get across the Rappahannock.

Twenty pioneers from McIntosh’s brigade came to the front. Lieutenant Browne reported that his New York battery loaned three of its felling axes to the cavalry. Chamberlain led another charge of the 4th New York Cavalry. About 100 dismounted cavalrymen peppered the Confederates with a heavy fire, hoping to force them to keep their heads down. The pioneers hacked at the abatis with their axes but made little headway through the tightly tangled brush. Slowed by the barrier, the riders came under heavy enough fire that this second charge was also thrown back.

The bluecoats unlimbered two guns and placed them where they could rake the Confederate position. But the guns remained silent at Averell’s orders because the general worried that the noise of the cannons would carry farther than the popping musketry and might result in the arrival of enemy reinforcements.

Determined to make a more forceful attempt, Chamberlain handed his valuables to another officer before riding into the ford again. This next charge also stalled in the face of the fire from Breckinridge’s sharpshooters, and the horsemen turned around and rode for safety. Chamberlain was knocked out of the saddle by a ball that tore into his left cheek and down into his neck. Some of the pioneers helped him out of the river. It was said that, sitting on the ground and nearly blinded with blood, Chamberlain fired all the rounds from his pistol. Because his vision was blurred, his firing endangered the fleeing New York troopers. By that point in the clash, a Rhode Island lieutenant had been killed at the ford, and a lieutenant of the 4th New York Cavalry was mortally wounded.

Chamberlain picked 20 men and assigned them to Lieutenant Simeon A. Brown of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry. He ordered them to cross the river and not return. Right behind Brown’s troopers were the Pennsylvania pioneers, now wielding their axes on horseback. The two detachments blended together, the Pennsylvanians wielding their pioneer axes high, reminding at least one chronicler of medieval warriors armed with battle axes.

The Rebels fired into the enemy riders as the pioneers chopped at the abatis, opening and widening passages through the barrier. Only three men made it across on unwounded horses. Brown’s horse was hit twice, and three bullets cut through the lieutenant’s coat; nevertheless, he made it across. As he waved his saber to signal the rest of the force to follow, the pioneers started cutting through the obstructions on the south bank.

Some final shots flew at the Yankees riding through the water. A bullet hit Colonel Alfred N. Duffie’s horse, and the French-born officer fell into the river. The colonel, uninjured, was fished out of the cold water and brought onto the shore.

Breckinridge ordered his men to abandon the rifle pits. Some of them did not hear his order and were quickly rounded up as more Yankees rode up onto the bank. Trying to ßescape on foot to their horses, which were hundreds of yards away, some of the men were ridden down and seized as captives. Averell reported that 25 prisoners were taken from the captured rifle pits; however, Captain Breckinridge managed to get away.

After just 90 minutes Kelly’s Ford was in Union hands. It took two hours to widen the gaps in the abatis, water the horses, and squeeze the entire force across the narrow ford. Another cause of delay was that the water was deep enough to flood the artillery’s limber chests. To keep them dry, about 300 rounds of artillery ammunition had to be carried one by one by cavalrymen using their feed bags.

The sound of battle at Kelly’s Ford did not carry the eight miles or so to Fitzhugh Lee’s camp at Culpeper Court House. A dispatch sent to Lee early that morning went astray, so it was about 7:30 amwhen he learned of the attack.

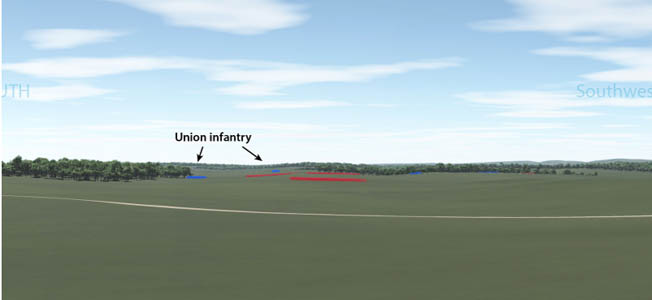

After sending away wagons and disabled horses, Lee’s five regiments had approximately 800 men. Lee rode with them toward Kelly’s Ford. Accompanying his force were the two guns from Captain James Breathed’s battery of horse artillery. As they neared the Rappahannock, Averell’s scouts spotted them, and the Yankee general deployed his men in line of battle about half a mile west of the ford.

Averell stationed McIntosh’s 3rd and 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry to hold the right, anchored on the Rappahannock at Wheatley’s Ford. To the left, he sent the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Both flank regiments were armed with new Spencer breech-loading carbines. Behind McIntosh, Captain Marcus Reno held two regiments in reserve, the 1st and 5th U.S. Cavalry. In the Union center were two guns of the 6th New York Battery. Holding the rest of the Union left was Duffie’s brigade, much of it behind a long stone fence and bolstered in the brigade’s center with two guns.

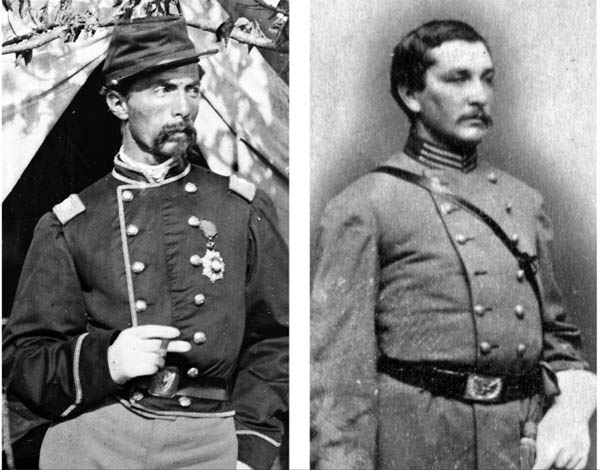

Fitzhugh Lee’s commanding officer, Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, had been at Culpeper Courthouse at a court-martial. Also in town were two of Stuart’s staff officers, Captain Harry Gilmor and Major John Pelham. Pelham’s daring actions at the Battle of Fredericksburg, in which he delayed the Union attack against Prospect Hill on the Confederate right flank with just one cannon, earned glowing praise from General Robert E. Lee, who in admiration called him “the gallant Pelham.” Pelham seems to have been in Orange County en route to his camp when he heard word of Averell’s raid and made his way to join Stuart.

Gilmor recalled that while Stuart examined the enemy line through his field glasses, Lee halted and drew up his men on the left side of the road running from the Orange & Alexandria to Kelly’s Ford. “General, I think there are only a few platoons in the woods yonder,” Lee said to Stuart. “Hadn’t we better ‘take the bulge’ on them at once?” This was one of Lee’s favorite expressions, and it meant that he wanted to gain the advantage over, in this case, the troops in the woods.

Stuart agreed that there was no time to waste. Lee first sent the sharpshooters of the 1st Virginia Cavalry against the enemy. As the sharpshooters went out on foot, their commander, Captain James Bailey, led them on horseback. Gilmor followed the sharpshooters and temporarily took command when Bailey’s horse was shot.

Sending his men forward, Gilmor quickly found there were more than a just few platoons behind the stone fence. The fire from the Spencers and the four Union cannons halted the Confederate advance 200 yards from the fence. Gilmor’s men wavered and then began to retreat under the heavy fire.

Stuart rode forward and stopped among Gilmor’s and Bailey’s men. “At every moment I expected to hear the dull [thud] of a bullet, and see him fall,” recalled Gilmor. “‘Confound it, men, come back,’ [Stuart] said, and they did.”

Desperate to get Stuart out of harm’s way, Gilmor insisted the men would go anywhere they were ordered. Stuart sent them to take cover behind a sod fence about 50 yards closer to Averell. They had barely settled in behind the fence when a shell burst and struck 10 men, three of them fatally.

The 3rd Virginia Cavalry, supported by the 5th Virginia Cavalry, charged the enemy line. Sabers aloft, they galloped in column of fours toward the stone fence. Pelham was unable to stay out of the battle. Adjutant Major H.B. McClellan had orders to keep the 3rd Virginia Cavalry’s column “well closed up,” the major wrote after the war. “I saw Major John Pelham rushing to its head with the shout of battle on his lips,” recalled McClellan, who was riding in the middle of the column.

When the Virginians ran up against the stone fence, they found it too high to surmount. Behind the masonry wall, already outnumbering the Rebels, the Union soldiers were able to unleash a veritable storm of bullets with their new Spencer carbines. The Model 1860 carbine held seven rounds in a tubular magazine that could be quickly replaced when empty. Soldiers reached a rate of fire of about 18 rounds per minute, about six times the rate of a muzzle-loaded musket or carbine.

Looking for a gap in the enemy line, the Confederate horsemen noticed a cluster of farm buildings in the distance to their left. Hoping to find an opening, they rode along the fence and, some distance down, found a small gate. As the last of the regiment passed through the opening in the fence, McClellan stopped to help an officer who was “struggling to place the body of a comrade across the bow of a saddle,” recalled McClellan.

McClellan recognized the stricken soldier as Pelham. A Union shell had exploded near the legendary officer, driving a small iron fragment into the back of his skull. Pelham was conveyed to the rear and died later that night.

The two Virginia regiments failed to turn the Union right. Colonel Thomas Rosser of the 5th Virginia Cavalry despaired as his men flowed away toward the rear. “Why in the name of God don’t you assist me in rallying the men?” he shouted to Major John William Puller.

Puller was leaning forward, holding onto the neck of his horse. “Colonel, I’m killed,” replied the major. Moments later he fell from his saddle. Some of his men dragged Puller to the rear, but he died a few minutes later. (Puller was the grandfather of World War II U.S. Marine General Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller.)

As the Virginians reeled back from the Union right, McIntosh’s men and the reserve troops remained in place, following Averell’s orders. Uncertain of the enemy’s dispositions, the general did not want to risk a repulse of his own troops.

Colonel Duffie was not so patient. A former officer in the French Army, he had served in African colonial wars as well as the Crimea. He ordered his cavalry regiments, the 1st Rhode Island, 4th New York, and 6th Ohio, to charge.

“As I have often seen it before, at the first sound of a gun, larger than a musket, the reserve was suddenly changed to the advance,” wrote a 5th U.S. Cavalry trooper. Although Duffie was defying his orders, Averell supported the eager volunteer colonel with two squadrons of the 5th U.S. Cavalry.

Breathed’s guns dropped a few shells into the Union horsemen. Sergeant Truman Reeves of the 6th Ohio Cavalry was near Lieutenant George W. Wilson when a shell exploded 10 feet over their heads sending shrapnel flying in all directions. “The sulphur in the shell, bursting so close to our heads, took the power of speech from Wilson, and he did not speak a loud word for more than a week,” wrote Reeves. “The bridle reins were cut entirely from his hands.” Despite the closeness of the shell, neither man was seriously wounded.

Fitzhugh Lee, with his fresh regiments (the 1st, 2nd, and 4th Virginia Cavalry) rode to meet Duffie head on. Truman Reeves thought the charge was “like the coming together of two mighty railroad trains at full speed.” Hundreds of riders clashed, emptying revolvers and hacking with their sabers. Men were shot at such close range that the pistol flashes scorched their jackets.

“[Amid] the yelling of men, the clashing of sabers, [there were] a few empty saddles, a few wounded and dying,” wrote Reeves, who rode ahead into the thick of the fight. After Reeves thrust his saber into the neck of one enemy horseman, “another Johnny came up on my right and struck my saber with such force that it went spinning in the air,” recalled Reeves. “At the same instant one of my company, by the name of Enos Hake, came up and shot the Johnny. If he had not, I fear that I would not now be alive to tell the story. It would be hard to describe to you the feelings of one left as I was, without a saber … with hundreds of the enemy around me. But I drew my revolver and sallied in again.”

While Duffie’s troopers clashed with the Virginians, “there were many personal encounters, single horsemen dashing at each other with full speed, and cutting and slashing with their sabres, until one or the other was disabled,” wrote a New York Times correspondent. “The wounds received, by both friend and foe in these single contests, were frightful; such as I trust never to see again.” Major Preston Farrington of the 1st Rhode Island was shot in the neck, but slowed the bleeding with his handkerchief and remained on the field.

Meanwhile, McIntosh’s troops pushed ahead on the Union right. The advancing Union line extended past both flanks of Lee’s smaller force, and Duffie’s regiments drove the Confederates across the field.

Major Cary Breckinridge of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry leapt his horse across a ditch, but his mount was shot and the major was taken prisoner. A brother of Captain James Breckinridge, who commanded the picket post at the ford, the two were cousins of John Cabell Breckinridge, Confederate major general and a former vice-president of the United States.

A squadron of the 1st Rhode Island rode far ahead after the retreating Confederates. With them was Duffie’s assistant adjutant general, Lieutenant Nathaniel Bowditch, an officer of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry. Bowditch charged ahead and was seen unhorsing two Rebels as he swept into the melee. His attention fixed on a Confederate who was firing at him with his revolver, Bowditch was unaware of another Rebel who rode up close enough to strike him from behind. Until that moment, he had assumed he was with Duffie’s men; instead, he saw that he was alone and surrounded by Rebels. He turned his horse to flee, but his horse was shot down. As his horse fell, Bowditch was struck by a bullet and a saber blow.

Two officers and 18 men of the 1st Rhode Island were taken away as prisoners. Bowditch remained on the field for some time before he was carried back to the rear. He died later of his wounds in a field hospital.

The violent clash of sabers and pistols ebbed as the Rebels withdrew. “A charge of this kind is usually over in less than five minutes, with many men lying on the ground, and many horses riderless, tearing around as if mad. Sometimes the rider is being dragged with one foot in the stirrup, and if not killed outright by the enemy would surely be by his own horse,” wrote Reeves.

Averell might have been pleased with Duffie’s successful charge, but he regretted that his force did not achieve greater results. “Had it been possible to reach the enemy’s flank when Duffie charged with the 5th U.S. or the Third Pennsylvania, 300 to 500 prisoners might have been captured, but the distance was too great for the time … and the charge was made three minutes too soon,” he wrote.

The Virginians passed through a thinly wooded tract into another clearing. There, behind a stream called Carter’s Run, they formed a second battle line about one mile west of the stone fence. The 3rd and 5th Virginia Cavalry remained on the Confederate right, the 1st Virginia held the center, and the 2nd and 4th Virginia awaited on the left.

Although Averell greatly outnumbered the Virginians, he did not attack. Instead, he settled in and waited, while his artillery bombarded the Rebels. Lee, who believed that Averell would be overly cautious, ordered another charge. His entire brigade moved forward, beginning with the regiments on his left. “From the very beginning of the charge, Lee’s regiments were subjected to the fire of the enemy’s carbines, and of shell, spherical case, and double-shotted canister,” recalled McClellan.

Sergeant W.J. Kimbrough of the 4th Virginia cavalry distinguished himself that afternoon. Kimbrough had been wounded earlier in the battle but refused to leave the field. During the charge, he dismounted and opened a fence for his comrades. Remounting, he rode at the head of the column until, “twice sabered over the head, his arm shattered by a bullet,” he was taken prisoner, wrote Lee. Kimbrough was not finished, though. That night, conveyed as a captive across the Rappahannock, he escaped and walked 12 miles to his camp.

Averell’s heavier numbers blunted the Confederate attack and began pushing the Virginians back again. Withdrawing across a stubble field, the Rebels set fire to the dry stalks, but Yankee troopers put out the fire by smothering the flames with their overcoats. Breathed’s guns kept up their fire on the Yankees with a precision Averell described as “exceedingly annoying,” striking down several troopers.

The 6th New York Battery was running low on ammunition. Even worse was the quality of the Union shells. One section of the battery discovered 18 of their shells were the wrong size and could not fit in their guns. Many of the shells had defective fuses. “Five-second fuses would explode in two seconds, and many would not explode at all,” wrote Averell.

Another Confederate charge surged at the Union right. McIntosh’s troopers, together with some of the 5th U.S. Cavalry, repulsed the Virginians. The intrepid Union horsemen pursued them until they reached a line of Confederate rifle pits, which could not be easily turned.

After the day’s fighting, Fitz Lee’s brigade was so worn down that the Union cavalry seemed on the verge of winning a spectacular victory, hovering in front of a smaller and battered enemy force. Had Averell not detached nearly one third of his force to guard against unlikely Confederate attacks that never happened, his horsemen might already have overrun the Confederates and pushed on to their main camp.

The naturally cautious Averell had good reasons for hesitation. Lee was not beaten yet, and his skirmishers once again were moving up to harass the Union left. There was a report of enemy infantry moving in. From the Orange & Alexandria tracks, only a couple of miles away came the sound of a train that might have been carrying Confederate reinforcements. It was about 5:30 pmand near the end of the day’s light.

Averell was pleased enough with what his men had done. They had crossed sabers with some of the finest cavalry regiments of the Confederate Army and had more than held their own. The commander sent his reserve, the steady regulars of Reno’s U.S. Cavalry regiments, to the front. Reno’s men served to screen the withdrawal of the battery as the volunteer regiments withdrew one by one to Kelly’s Ford. During this time, Captain Marcus Reno’s horse was killed, and the captain was seriously injured when he was trapped under the horse when it collapsed. Reno was breveted to major for his role at Kelly’s Ford. He is most famous today for having served as George A. Custer’s second in command at the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

The bluecoats had withdrawn north of the Rappahannock by 7:30 pm. “Arriving at Morrisville, each man built himself a fire, rolled himself up in his blanket, and slept as soundly as if no rebels were to be found this side of South Carolina,” wrote a 5th U.S. Cavalry trooper.

Just as at Hartwood Church, a doctor stayed behind to tend some wounded who were too badly hurt to be moved. This time it was a Union Army surgeon who bore a letter for an enemy general from an old friend. When Fitzhugh Lee visited the hospital, the surgeon presented the Rebel general with the gift of a bag of coffee from his old classmate Averell. With the coffee Averell added a note, which read, “Dear Fitz, here is your coffee. How is your horse? Averell.”

From a strategic standpoint, Kelly’s Ford ended as a draw. After a day of sharp fighting, both armies were back in camp on their own sides of the Rappahannock. Both sides could, and did, claim victory. Lee’s troopers still held the south bank of the river after the enemy withdrawal, and they knew they had fended off a force more than twice their number. They had fought so well that Averell’s men were convinced they faced a far larger enemy force than they did.

The note that Fitz Lee left for Averell at Hartwood Church back in February, which in a way touched off the whole action at Kelly’s Ford, seems to have been lost. Averell later claimed he gave the note to U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, and he was told that the president “carried the note in his pocket for a long time and would frequently show it.”

Kelly’s Ford was a small-scale action compared with the two major battles, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, that bracketed it in the war’s chronology. Union casualties included one officer and five enlisted men dead, 12 officers and 38 men wounded, and two officers and 29 men captured or missing. The 42 casualties of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry, which took the brunt of the fighting when forcing the crossing of the Rappahannock, accounted for more than half of the total of 78.

Confederate losses were much heavier: three officers (including the irreplaceable Pelham) and eight men dead, 11 officers and 77 men wounded, and Breckinridge and 39 men taken prisoner. The total of 133 casualties was more than 15 percent of the men Fitzhugh Lee had present on the field. Upward of 170 of Lee’s horses were killed, wounded, or taken. This was a sharp loss when good horses were becoming scarce in the Confederacy.

The month after the cavalry clash at Kelly’s Ford, Hooker established a unified cavalry command. Up to that point, the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry had operated in three unrelated divisions. Hooker consolidated these divisions into a 12,000-man cavalry corps under the command of Maj. Gen. George Stoneman. He then sent Stoneman on a raid to sever the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia’s line of supply in the hope that it would force General Robert E. Lee to withdraw his army from its strong position at Fredericksburg.

As the largest all-cavalry battle yet fought in the Eastern theater, the Battle of Kelly’s Ford would have a symbolism far greater than its immediate results. It marked the beginning of a permanent change in the conduct of the war in Virginia. The days of Stuart’s easy rides around or through much larger Union forces were over. Lincoln’s cavalry was no longer cowed by the legendary Stuart and his cavalry.

The Army of the Potomac’s cavalry would surprise the Confederates with its bold confidence in June 1863 at Brandy’s Station in Culpeper County, Virginia. The battle marked the end of the Confederate cavalry’s dominance in the East.