By Jim Campbell

Because it was such a long and cataclysmic event, World War II still resonates with so many of us. Books, magazines, movies, television, and other media continue to document the details. However, some stories are missed or glossed over, or simply forgotten.

A football team and a group of boosters and followers from a college in the Pacific Northwest would never forget what happened a day after their December 1941 game in Hawaii.

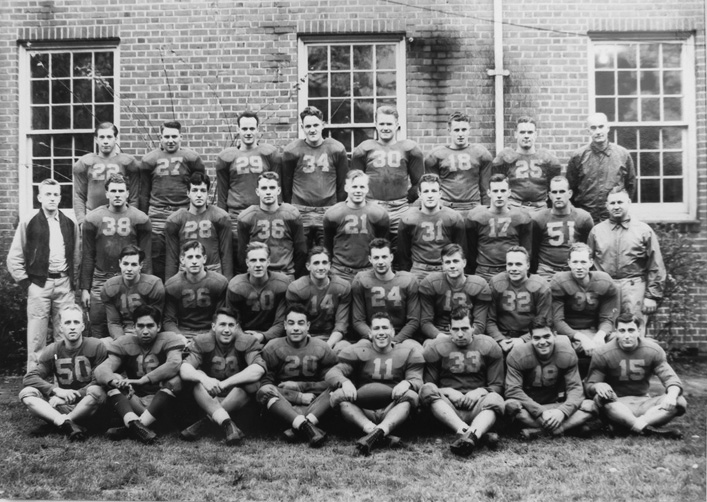

Willamette University is located in Oregon’s capital city of Salem, along the banks of the Willamette River. It was founded nearly 175 years ago, “the oldest university in the West.” The school had a highly respected football program under head coach Roy “Spec” Keene. Keene was able to arrange for the Bearcats to play in a Shrine Bowl game against the University of Hawaii in Honolulu on Saturday, December 6, 1941. Willamette was given a $5,000 guarantee—enough to cover the expenses of the trip and still realize a modest profit for the athletic department.

The team knew in advance that it would be going to the islands. Coach Keene was no dummy. He used the trip to Hawaii as a means of recruiting players who perhaps would have been able to play at larger, better known colleges and universities. While recruiting in 1941 was not nearly as complex and competitive as it has become today, players were quite aware of the trip.

Ken Jacobson of the Bearcats said, “We knew what was at stake. We played a little tentatively the week before we were to set sail. It was like we were playing not to get hurt. No one wanted to miss the trip, and we had more trouble than we should have in beating Whitman [College], 28-0.”

The Willamette team and party boarded the Matson Line’s passenger ship Lurline on November 27 after a train trip—a first for many of the players—to San Francisco.

Also aboard the Lurline was the San Jose State football team, set to play the University of Hawaii at a later date. That game was never played, an early casualty of World War II.

The Bearcats, victors by large scores in seven of their prior eight games, losing only to the University of Idaho (a member of the Pacific Coast Conference, forerunner of today’s PAC-12), would lose the game to the Rainbow Warriors 20-6 on that balmy December Saturday in 1941, but a larger story was unfolding.

As the Willamette Bearcats were sailing west for their island date, a Japanese naval task force under Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto was sailing easterly and stealthily toward a like destination, the Hawaiian island of Oahu, more specifically Pearl Harbor.

Along with the Bearcats, Wayne Hadley and Shirley McKay, whom Hadley would marry in November 1942, were with the Willamette party that sailed in 1941.

They checked into the exclusive Moana Hotel. Hadley explained that Willamette was not being spendthrift. He said, “You have to remember that this was long before all those high-rises you now see. The only hotels of Waikiki were the Moana and the Royal Hawaiian. That was it, not much choice.”

After the Lurline docked to an elaborate aloha reception of colorful flowered leis and welcoming kisses from University of Hawaii coeds, the host Shriners conducted a tour of Honolulu and took the team and boosters out a pass to Pali Mountain and the Punchbowl.

Wally Olson, a center for Willamette’s “Cardinal & Old Gold,” was not so sure the trip would come off as advertised until actually arriving in the islands. He said, “We expected the trip to be canceled—because of war tensions—right up until we actually set sail, but once we got underway and landed we never thought a sneak attack would occur; the place was just so beautiful and serene. And who would attack such a heavily fortified place? The Army and Navy were everywhere. You couldn’t take two steps in any direction and not see a soldier or sailor.”

Apparently, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel and General Walter C. Short, the Navy and Army commanders in Hawaii, shared Olson’s feelings of false security. While it was felt that the Japanese could or would attack—there had been much radio chatter and even intercepted coded messages from the Japanese—it was the general consensus that the more likely targets were the Philippines or Malaya.

Earl Hampton, a Bearcats fullback, remembers that the game was played at Honolulu Stadium before a crowd of 26,000, about one-tenth of Honolulu’s population at the time. “It was a hard fought game. They were bigger than we were, but we played well for about three quarters. We actually scored first, but then they pulled away in the final quarter. Several of our guys were still suffering from seasickness. Remember none of us had ever sailed on an ocean-going vessel. It was freezing when we left Salem; when we got to Honolulu, it was 85 degrees. We still had our sea legs and just ran outta gas.”

Marshall Barbour’s impression of the game was mostly one man, Nolle Smith, known as “the fastest man in the islands.” Smith, a slim but swift, 160-pound halfback, could really run, according to Barbour. He said, “He was quick and shifty. We saw a lot of him, from the rear, all day.”

Tackle George Constable echoed Barbour, “You ask what I remember most from the game—simple, seeing the back of Nolle Smith’s jersey all afternoon.

“But Ted Ogdahl made the play of the day. If ESPN had existed, it would have made the top 10. He tackled Smith from behind after a long chase. Still don’t know how he did it. He was not a sprinter, though he was a much better than average halfback.

Ogdahl later coached the Cardinal & Old Gold for 20 successful years, 1952-1971.

The mercurial Smith also impressed center Pat White, “I thought I had him [Smith] once. I was covering him on a flat pass. He was up in the air, both feet off of the ground, and I drove my old leather helmet right into him, thinking I really nailed him. Funny, I felt the collision more than he did. Al Walden, Chuck Furno, and Ogdahl were our best backs—they were very good football players. But Nolle Smith and his team were just better than the ol’ Cardinal & Old Gold that day.”

White recalled the next fateful day. “We were up early on Sunday the 7th to take a scheduled bus tour of the island and then picnic on the North Shore with a group of U of H coeds. But the bus never showed. Some Army MPs herded us back to the hotel.”

Halfback Furno had similar recollections. “The Army and the Navy were just about everywhere around our hotel, telling us where to go and what to do, but we didn’t know what all the hustle and bustle was about at first.”

Hadley and McKay were also waiting for the bus that never came. Hadley said, “We began to hear stories that the bus wasn’t coming, just that it wasn’t coming—no explanation. So, Shirley and I decided take a walk down to Waikiki Beach for a swim. We began to see offshore splashes and airbursts, but like so many others, we thought it part of Navy maneuvers. Shirley remarked ‘how realistic’ they looked. Neither of us realized we were eyewitnesses to the start of World War II for the United States. Mostly, we just heard the noise—planes flying, bombs dropping, explosions. Pearl was only about eight miles away. It was a sight we’ll never forget.”

Constable had a much different perspective on the early Sunday morning attack. “We were on the roof of the Moana watching what we thought were pretty authentic maneuvers. We heard shells exploding, saw splashes in the water, but were kind of oblivious as to what was really happening. Ironically, I had a Kodak box camera in my room, but I wasn’t going to go down to get it just to take snapshots of ‘practice runs.’”

White remembered what happened once it was evident that the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor was under attack. “Coach Keene quickly ‘volunteered’ our services to the Army. We were all issued rifles. Even though we were mostly rural kids from Oregon, we hadn’t had much experience with guns. We were given the most basic of instruction, nothing too detailed about the use of the weapons, which were from World War I.”

“Mush [Barbour’s nickname] and I went down to Waikiki Beach to string barbed wire. We dug some trenches, too. It wasn’t too far-fetched to think that a Japanese landing force was set to invade. Later machine-gun emplacements were set up. Some of us protected them. Still later we went with some others to stand guard at the Punahou School up in the hills. The Army Corps of Engineers had taken over the school as their headquarters and used it as an ammo depot.”

While White and Barbour were pulling guard duty that Sunday evening at Punahou, White recalled a scary incident. “We were standing guard at a water tower, and our relief, two other Bearcats, came down the hill early. We had expected them to come up the hill. Mush and I both thought that Jap paratroops had landed and we were about to be ‘duck soup.’ We might have shot them, or at least shot at them, had we not recognized them in the flashlight beams. I guess, like everyone else, we had itchy trigger fingers.”

Olson also saw splashes while eating breakfast at the Moana. His waiter told him what he saw were “just whale spouts.” Olson said, “We were just farm boys and lumberjacks, but after about dozen eruptions in the water we knew that something was up and it wasn’t good. There couldn’t be that many whales out there.”

Glenn Nordquist was a 200-pound freshman tackle for the Bearcats. He said, “When I was a teenager, I decided that I would study for the ministry, but then I had some success as a high school football player and thought that that was for me. That’s what I wanted to do. Coach Keene’s pitch of a trip to Hawaii sealed the deal for me. But I would soon learn differently. While walking guard at Punahou at night, I had a very long and personal talk with the Lord, and I knew what I had to do. After returning to Willamette and finishing my freshman year, I transferred to Bob Jones University in Greenville, South Carolina. I graduated, went to seminary, and became a pastor.”

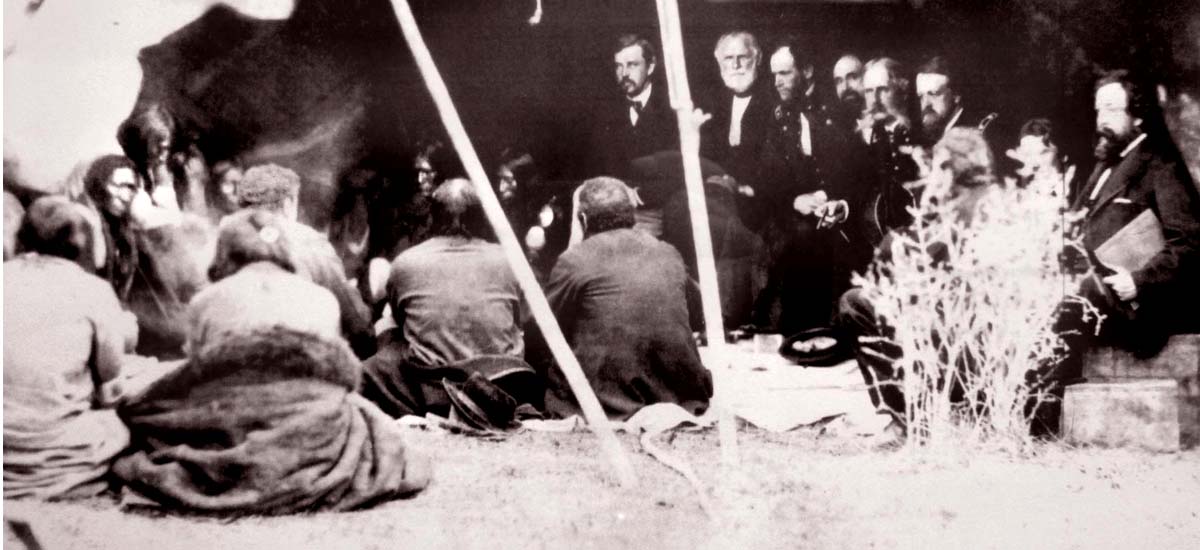

In his ministry throughout the Northwest, Nordquist, later a prison chaplain in Florida, made an unlikely acquaintance. He was surprised to find that he was on the same program at a youth rally at a small Oregon Baptist church as Captain Mitsuo Fuchida, the pilot who led the first wave of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Fuchida had converted to Christianity not long after the war was over and was on a speaking tour of the United States.

Hampton related a close call during the attack. “I was out on the street when I heard and saw a big explosion about two blocks away. I figured it was one of the Japanese dive bombers dropping his last bomb before leaving the attack. Believe me, I knew then and there that we were in a real shootin’ war!”

The uncertainty of what was actually happening as the United States was pulled into World War II led to some odd situations. Ogdahl recalled a night of guard duty. “We were all a little trigger happy, even those who had little or no experience with firearms. There were lots of coconut trees around the school, and occasionally a coconut would drop and make ‘clunking’ noise. We couldn’t be sure what it was, but we were ready to shoot first and ask questions later, as they say in the old Western movies. Luckily, no one was shot, but it was a little scary.”

The Willamette party stayed on Oahu for 10 days doing what they could to support the war effort. The players continued to walk guard around the clock, six hours on, four hours off. The relatively few women of the party helped by assisting nurses at the Tripler Army Hospital in caring for wounded and burn victims.

Shirley McKay was one of those assisting. She said, “We helped with a group of children who were wounded by stray shrapnel walking to Sunday School. We fed them, read to them. We did what we could to ease their fears and comfort them.”

Later, while sailing back to San Francisco, the Willamette women also helped with the wounded. Shirley recalled a young sailor who had lost an arm. “He said that he was a baseball pitcher and wondered how he was going to pitch with one arm—it was heartbreaking, but just one of many sad stories.” Ms. McKay was the daughter of state senator Douglas McKay, later Oregon governor and President Dwight Eisenhower’s Secretary of the Interior.

Coach Keene was in a quandary. How do I get my team and the rest of our group back to the States? After scrambling for a solution, the answer came in the form of a luxury ocean liner, the President Coolidge. The ship sailed into Honolulu with refugees from the Philippines. There wasn’t much room. The ship already had 400 more passengers than the intended 800 capacity. Keene used his considerable powers of persuasion to wrangle space for his Bearcats and the rest of the group. In exchange for accommodations in steerage, the Willamette group would attend to the 150 wounded servicemen, mostly serious burn victims and amputees, being evacuated to the mainland. The Coolidge set sail on December 19.

The men and women of Willamette did what they could. Both assisted in the care of the wounded. The men helped out by moving them. The women continued to assist the overworked nurses in changing dressings or sometimes just providing a sympathetic ear or writing a letter home to assure worried families that their boys had at least survived the initial attack.

Goodman, who made Little All-America that fateful season, was a versatile athlete, lettering also in baseball, basketball, and track and field. He echoed the concerns of the other players when he said, “We were in steerage, which is below the water level. We heard of ships being torpedoed by Japanese submarines and knew that we wouldn’t have much of a chance if we were hit by one. For that reason, after about two days out, many of us took to sleeping out on the open deck rather than going below.

“When we started out from Honolulu, we were accompanied by destroyer escorts. As we got closer to San Francisco actual destroyers guided us in the open waters. Another tactic, one that led to a longer and more apprehensive voyage, was that the ship would change course about every 15 minutes—zigzagging to make ourselves less of a target for the enemy subs as the shipping lanes narrowed as we neared San Francisco.”

Jacobson recalled, “As we got closer to port, we could pick up radio. There were broadcast reports of Japanese submarines sinking ships in the Pacific. On the last night out before reaching port, I don’t think any of us slept much, if at all.”

McKay recalled sighting the California coast. “We were still several miles out to sea, but we could see land. California never looked so good. We were all elated, not to mention thankful. I’m not sure how it started, but we all started singing a popular song of the time, ‘California Here I Come.’ I know we were off key, but to us we were as good as the Andrews Sisters. As we sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge, a special feeling came over all of us. I’ll never forget it.”

Perhaps not all the crowd that gathered at the dock were there to welcome the Willamette team and followers, but a welcoming group of about 1,000 was on hand, waving and cheering as the President Coolidge docked. Of course, family, friends, and well wishers from Salem, Oregon, were there. Joy, relief, and gratitude were just some of the emotions that were expressed as loved ones returned safely. The ship’s arrival on December 25 made it a special and unique Christmas Day.

The celebration continued on the train trip back to Salem. Illustrative of the spirit of the times, all 28 members of the Bearcats team enlisted in the armed service shortly after arrival back home. Only Bob Reader, killed in action, did not survive the war.

The president of Willamette, Carl Knopf, received a letter from Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox commending the Cardinal & Old Gold players for their service during and after the Pearl Harbor attack.

In 1997, the Bearcats team of 1941 was inducted en masse into the Willamette University Athletics Hall of Fame. Ted Ogdahl, Marvin Goodman, coach “Spec” Keene, and assistant coach Dick Weisgerber were inducted previously on an individual basis.

Also included in the team’s induction were Wayne and Shirley McKay Hadley.

Marvin Goodman’s wife, Gloria, related the thoughts of her husband and undoubtedly others. “Marvin, and I’m sure other players and members of the Willamette party, wondered how many of the soldiers and sailors who watched them play on Saturday were casualties of the Pearl Harbor attack on Sunday.”

Author Jim Campbell is contributing to WWII History for the first time. He resides in Selinsgrove, Pennsylvania.

Join The Conversation

Comments