By Eric Niderost

On September 2, 1945, Japanese representatives boarded the battleship USS Missouri, riding at anchor in Tokyo Bay, to sign an instrument of unconditional surrender. World War II had been brought to a swift conclusion thanks to the atomic bombs that had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. To the men of the III Marine Amphibious Corps (IIIAC), already training for the proposed invasion of Japan, this was welcome news indeed.

The leathernecks knew that an invasion of the Japanese home islands would have been bloody. It was projected that the invasion might cost the Allies a million casualties and prolong the war by two or three years. Now the nightmare seemed over, and the Marines looked forward to returning to the States.

But instead of going home, the IIIAC Marines found that they were going to be sent to China instead. This was a bitter disappointment for many, but some actually looked forward to an adventure in the Far East. Private Harold Stevens of the 29th Marines was thrilled that he was not going back to his family’s farm in Pennsylvania. He was only 19 but was already a veteran of the bloody battles that secured Okinawa.

To many Americans of Stevens’ generation, China was still the land of mystery and romance, of exotic sights and beautiful women. It was a place that had enthralled Marco Polo. Now Stevens, a farm boy, was about to be sent there. He could hardly believe his good fortune.

The story of the postwar Marine involvement in China is interesting but anything but romantic. It began when Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, leader of China during World War II, requested American help in securing northern China. There were more than two million Japanese there who had to be repatriated to Japan, including a substantial number of soldiers. But Chiang was also thinking of his chief rival, Communist leader Mao Zedong. The communists were particularly strong in the north. With American help, directly or indirectly, Chiang hoped to seize the important cities of northern China before the communists could gain control.

While the U.S government did help transport Chiang’s Nationalist troops to various locations, in general the American military was to maintain strict neutrality. In October 1945, the U.S. Fourteenth Air Force airlifted 50,000 men of the 92nd and 94th Chinese Nationalist Armies to Peiping (Beijing) and other key strategic points. While “cooperating” with Chiang and the Nationalists, the Americans thought they could bring about a permanent peace in China.

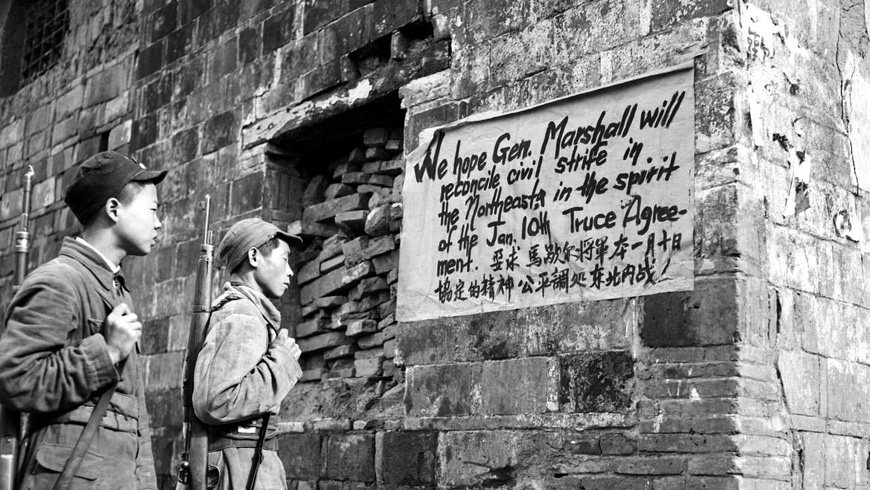

In fact, on November 1945, President Harry Truman appointed General George C. Marshal as a special representative to mediate the differences between the communists and Nationalists. Truman felt it was in the most “vital interest” of the United States and all the United Nations that the people of China overlook no opportunity to adjust their internal differences promptly through peaceful negotiation.

American foreign policy over the last 70 years has often been based on naïve thinking and well-meaning blundering. There is an underlying assumption that Americans have the “know how” to solve the insoluble. Deep cultural, religious, ethnic, and political differences are all too often downplayed or ignored in favor of an optimism that is almost always misplaced.

Such was the case in Vietnam, and such was the case in China from 1945-1949. The Truman administration was certain that General Marshall could negotiate a lasting peace between the bitterest of enemies, foes who mistrusted each other and who were stalling for time to gain a decisive advantage over their rivals. As a result, the Marine IIIAC was left “holding the bag,” trying to maintain a precarious neutrality in the face of a swiftly deteriorating situation.

In fairness, there were some “Old China hands” in the State Department who recognized that the Chinese government was riddled with corruption and warned the Truman administration accordingly. They were ignored. Though Chiang was no “prize,” he was anti-communist, and that’s all that seemed to matter. The Cold War was starting and with it a new “Red Scare” that communism would spread throughout the world.

The Marine IIIAC Corps headquarters together with the 1st Marine Division would occupy positions in and around Tangku, Tientsin, Peiping, and Chingwangtao in Hopeh Province. Air Support would be provided by the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing flying Grumman F7F Tigercats and other planes. The airmen would be stationed at airfields in the Tsingtao, Tientsin, and Peiping areas.

In the meantime, the 29th Marine Regiment, 6th Division was supposed to have landed at Chefoo, but plans had to be changed. The communists had already seized the city, and they were extremely uncooperative. And so it was that young private Stevens and the 29th Marines found themselves at Tsingtao (now Qingdao), a port on China’s Yellow Sea coast.

Tsingtao had been the administrative center of the German Concession that lasted from 1898 to 1914. These “concessions,” technically leased from China, were actually quasi-colonies of the various European powers. Even today, Tsingtao is noted for its historic German colonial buildings. Not everything the Europeans did was bad. In 1903 the Germania Brewery was founded and started to produce a beer that is the most popular brand in China today.

In the early afternoon of October 11, 1945, the first Marines landed at Tsingtao. When the main body arrived on October 15, they were given a tumultuous welcome by the Chinese population. Private Stevens tried to learn a few words of Chinese on the trip. When Colonel Roston, the battalion commander, heard that Stevens “knew Chinese”—a great exaggeration —he appointed the young leatherneck as official interpreter. Stevens did his best, even though all he knew were a few stock phrases like, “Do you have your own rice bowl?”

Though World War II was over, China was in turmoil. The war-ravaged economy and political uncertainty produced a raging hyperinflation. The exchange rate was 10,000 Chinese dollars to one U.S. dollar. A good meal might cost $190,000—about $19.00 U.S. There were plenty of bars and cabarets in the various Chinese cities.

Tsingtao was a fascinating city, but some aspects took some getting used to. Ragged beggars swarmed through the streets, a number that included many impoverished children. In fact, Private Stevens’ own outfit, Fox Company, 2nd Battalion, 29th Marines, unofficially adopted a little Chinese beggar who they nicknamed “Little Lew.” He was cleaned, fed, and dressed in cut-down Marine uniform items.

But elsewhere in China the news was not so heartwarming. Chiang had made a major tactical mistake that would ultimately cause his regime to collapse. The generalissimo concentrated on winning back Manchuria, in the process withdrawing many of his troops from northern China. This created a power vacuum that the communist Chinese were all too happy to fill. Tsingtao became a Nationalist “island” in a communist-dominated Shantung Province “sea.”

Even in Hubei Province the communists were suspicious and generally uncooperative. Marine Brig. Gen. William Worton had a meeting with Zhou En-lai, later famous as Mao’s right hand man and foreign minister for the People’s Republic of China. Zhou was a brilliant diplomat, and he made it clear that the communists would fight hard to prevent the Marines from entering Peiping.

Worton was not intimidated, even after a stormy hour with Zhou. He pointed out that the IIIAC was a battle-hardened unit with superior air power support. He was not looking for trouble, but his Marines could push through any opposition if they had to. Zhou En-lai had met his match, and he withdrew after insisting he would have Marine orders “changed.” The Marines arrived in Peiping without major incident.

The formal surrender of the 10,000-man Tsingtao Japanese garrison took place on October 25, 1945. The whole Marine 6th Division was on hand for the ceremony, conducted by division commander Maj. Gen. Lemuel Shepard and Chinese Nationalist General Chen Chao-Tsang. However, some Japanese troops were still needed to help keep the major rail lines open in Shantung. There were not enough Marines or Nationalist troops to guard all the railroads.

Even so, Marines often found themselves in the role of train guards, one of the most dangerous assignments in China. Winters were bitterly cold in China, and the great city of Shanghai, a metropolis of three million souls, needed a constant stream of northern coal to keep it going. Shanghai needed 100,000 tons of coal a month, so Marine riflemen, shivering from the icy blasts than swept in from the Gobi Desert, stood guard to keep the trains running.

Clashes between the Marines and communist Chinese insurgents started to occur and eventually became almost routine. The communists tried to sabotage the railroad tracks, and sometimes they would snipe at passing trains. In the clash later known as the Kuyeh Incident, the communists ambushed a train that was traveling from Tangshan to Chinwangtao. This was a special train carrying General Dewitt Peck, commander of the Marine 1st Division, and a Marine inspection team. The communists opened fire from the village of Kuyeh, only 500 yards from the railroad track.

A firefight erupted that lasted the better part of three hours. Air support was called in, but Marine pilots could not clearly distinguish where communist forces were lurking. There was a fear of hitting civilians too, so permission to open fire was denied. A relief force was dispatched from the 7th Marines, but when they arrived the communists had melted away into the countryside.

The train stayed overnight at Kuyeh, but when it started again the next day it was found the communists had torn up about 400 yards of railroad track. When Chinese railroad crews tried to repair the line, they were ambushed by waiting communist troops. General Peck gave up trying to reach Chinwangtao by rail. He turned back to Tangku and took a flight on an observation plane instead.

The incident showed how firm a grip the Chinese communists had on the province. General Peck felt a Nationalist offensive was needed to clear the vital rail links from communist interference. Peck contacted General Tu Li-Ming, who was in control of the Northeast China Command, to arrange such a sweep. Tu readily agreed but requested that Marines guard all large rail bridges between Tangku and Chinwangtao, a distance of about 135 miles. That way, more Chinese Nationalist troops would be freed up for the offensive.

Gradually the Marines began to realize their mission was morphing into something quite different than the original assignment. Private Stevens almost got into a fight when he mentioned that their main mission was to repatriate the Japanese. Hearing this, a fellow Marine exploded in anger. “Don’t give me that bullshit!” he said forcefully, “Marines are in North China to support Chiang’s regime.”

Many Marines also started to realize that Chiang’s government was so corrupt it was beyond saving. American servicemen were appalled by the extreme poverty they saw all around them, the careless indifference to human life, and practices like selling young Chinese girls into sexual slavery in brothels. Almost anything seemed better than the current government.

In 1946, the Marine forces in China were substantially reduced. The 6th Marine Division was disbanded, and the forces in Tsingtao were whittled down to a reinforced brigade. The Japanese repatriation was going well, ironically “helped” by the growing communist presence. Japanese nationals, both military and civilian, had no wish to be subject to the tender mercies of any Chinese, but they particularly feared the communists. As communist forces like the 8th Route Army advanced, the Japanese packed up and headed for Tsingtao, the main embarkation port.

The clashes between Marines and communist Chinese insurgents seemed to grow in number and seriousness. On July 13, 1946, communist raiders surprised and captured seven Marines who were guarding a railroad bridge. After some negotiations the leathernecks were released on July 24, but the communists adamantly demanded an “apology” from the U.S. government for “invading” a “liberated” area. The U.S. government ignored this posturing and issued its own strong protest in return.

Just a few days later, on July 29, 1946, a Marine convoy heading from Tientsin to Peiping was ambushed at Anping. The column consisted of cargo trucks, jeeps, and some U.S. Army staff cars carrying personnel bound for the Chinese capital. Second Lieutenant Douglas A. Corwin led the escort, which consisted of 31 men from the 1st Battalion and a 10-man 60mm mortar section from the 1st Marines. There were also some Marine replacements with the column.

The Marine convoy encountered a roadblock of oxcarts, so Corwin and an advance party went forward to investigate. Suddenly, a dozen hand grenades were thrown from some nearby bushes. Given no time to react or take cover, Corwin and the men immediately around him were all killed or wounded.

The convoy truckers and other personnel immediately jumped out of their vehicles and took cover. The convoy seemed to be trapped and was taking heavy fire from the right, left, and rear. Platoon Sergeant Cecil Flanagan now took command and ably directed return fire. The communists were apparently surprised that the column had mortars, and their attack plans were thrown off balance by well-directed rounds.

Every time the communists tried to mount an attack on the convoy, their troop concentrations were spotted before they could get far. Once spotted, the 60mm mortars went to work, lobbing round after round into enemy positions. The communists became so disoriented by this mortar fire that a Marine jeep from the rear managed to break through and go for help. The column did have radios, but unfortunately they had limited range.

The convoy battled it out with the communists for about four hours. A rescue force was dispatched immediately, and the communists finally gave up their attack. This had been the most serious incident to date. The communist force was estimated at 300, all armed with rifles, grenades, and automatic weapons. The Marine casualty count stood at five dead and 12 wounded. At least 12 communist Chinese soldiers were killed, and perhaps many more. The communists had a habit of carrying off their dead, making a good estimate extremely difficult.

By early 1947, it was clear that General Marshall’s effort to reconcile the Nationalists and communists was an utter failure. As a result, President Truman ordered all U.S. military home, but the disengagement was going to be a long and tedious one. Units were shifted around and finally withdrawn. It was clear that Chiang’s government was going to fall.

The last and greatest clash between American Marines and the Chinese communists took place the night of April 4-5, 1947. Mao’s forces, now dubbed the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), attacked an ammunition dump at Hsin Ho that was guarded by Marines. The Americans were heavily outnumbered; the attacking force was estimated at about 350 men.

The night’s quiet was broken by the shrill notes of a Chinese bugle call. It was the PLA’s style to blow bugles when launching an offensive. This same technique would be used later in the Korean War. Five Marines were killed in the initial assault, and the rest were hard pressed to keep the enemy at bay. The PLA commander had anticipated that American reinforcements would be sent, so he placed a mine in the road where relief would be expected at any moment.

Sure enough, a truck bearing a relief force made its way up the road and promptly hit the mine. The relief men jumped off the truck, and a sharp firefight ensued. The issue was in doubt several times, but the Marines finally gained the upper hand. Once again communist forces broke off the action and faded into the darkness. The enemy did manage to make off with some ammunition boxes, which seemed to be one of their main goals in the raid.

Private Stevens also had his share of adventure. He joined a small mission—only a handful of Marines—to try and rescue some nuns and Chinese orphan children in a remote place called Loh Shan. The mission failed because the nuns refused to leave. But worse was to follow. Stevens and his party were captured by bandits. All were executed, but Stevens was spared apparently because he knew Chinese.

Stevens was promptly turned over to a communist officer from the 8th Route Army. He became a prisoner with a Chinese character tattoo ID inked on his arm. Before long he found himself in a work gang on a coal storage island. The prisoners’ main job was to shovel coal to flat-bottomed boats moored along the shore.

“Mao was preparing for a major naval assault against the Nationalists,” Stevens says today, “and his ships needed coal to run their steam engines.” It was backbreaking work, but luckily he was transferred to help fishermen work their nets. He had to escape, had to get back to his unit. After some careful deliberation, he hatched an acceptable if risky plan. He would skull out in a small boat, pretending to check the nets that were farthest out.

Once in position, he would dive into the water and hopefully get picked up by a passing junk. It all unfolded as planned, except the water proved bitterly cold. A junk did indeed pick him up, and friendly Chinese crewmen pulled him out of the water half dead with cold. Later, the junk was intercepted by a U.S. destroyer. He was free!

In November 1948, the U.S. embassy issued a statement that declared any American citizen “who does not wish to remain in North China should plan to leave at once by United States Naval vessel at Tientsin.” By the end of the month, consular personnel, the remaining American civilians, and military dependents were being shipped out. The American presence in China, which dated to the first Yankee traders who sailed to Canton in the 1780s, was coming to an abrupt end. There would be no more contact with China until President Richard Nixon’s visit in 1972.

By the spring of 1949, the total withdrawal of American military forces was almost complete. In February of that year, the U.S. Marine Corps Air Facility at Tsingtao was disbanded. All the ground equipment was removed, and the planes of fighter squadron VMF-211 took off for their new home, the escort carrier Rendova. On May 25, 1949, Company C, 7th Marines, the last remaining American unit on Chinese soil, departed Tsingtao. It was truly the end of an era.

Author Eric Niderost is a frequent contributor to Sovereign Media publications. He has written on numerous historical topics and resides in Hayward, California.