By Chuck Lyons

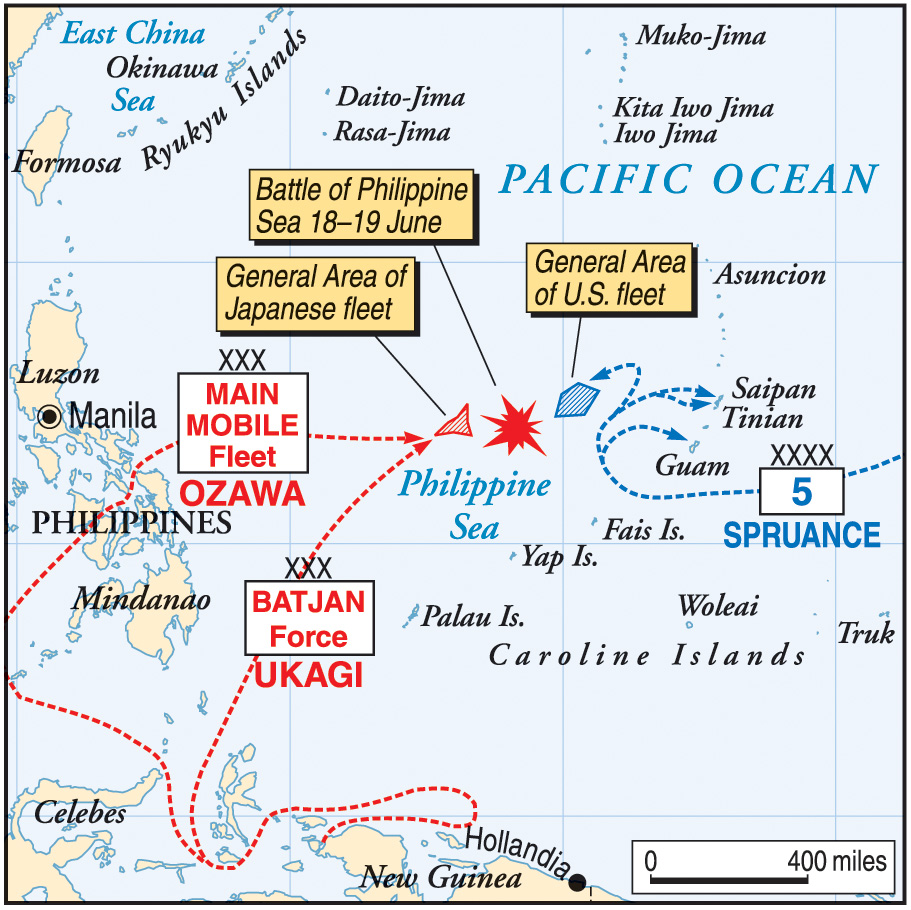

The Philippine Sea encompasses two million square miles of the western part of the Pacific Ocean. It is bounded by the Philippine Islands on the west, the Mariana Islands on the east, the Caroline Islands to the south, and the Japanese Islands to the north. In the summer of 1944 it was the battleground of two great carrier strike forces. One of these belonged to Japanese Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa. The other belonged to U.S. Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, and its carriers were under the tactical command of Marc Mitscher. Ozawa had explicit orders to halt the steady advance of the U.S. 5th Fleet, to which Mitscher’s carriers belonged, across the vast Pacific Ocean toward Japan.

Ozawa had the majority of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s fighting fleet under his command at the time, but his force of approximately 90 ships and submarines was still considerably smaller than the U.S. Navy’s 129 ships and submarines. He also commanded 450 carrier-based aircraft that would coordinate with 300 ground-based aircraft in the Marianas.

Ozawa’s strike force steamed east in two groups. The vanguard, comprising three small carriers, four battleships, and other vessels, plowed through the Philippine Sea 100 miles ahead of the main group, which was composed of six large carriers, a battleship, and a wide array of supporting vessels.

Ozawa’s strategy was simple. His vanguard would serve as a decoy to lure the U.S. carrier aircraft while the aircraft from the main group, reinforced with land-based aircraft in the Marianas, inflicted heavy damage in multiple attacks.

Ozawa had no intention of letting Mitscher land the first blow. Japanese carrier aircraft had greater range than U.S. carrier aircraft, and Ozawa planned to make the most of his advantage. In addition, Ozawa would be able to launch his aircraft into the wind. The U.S. carriers would have to turn around and sail away from the Japanese fleet to launch their aircraft into the wind.

What Ozawa did not know was that even before he launched his aircraft on June 19, Mitscher had derailed his plan by knocking out the Japanese ground-based aircraft in the Marianas more than a week earlier. Beginning on June 11, Mitscher had sent his aircraft against Japanese air bases on the islands of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian in the Marianas. Sweeps in the days afterward pummeled the targets repeatedly to ensure aircraft were destroyed and airstrips too damaged to use. When the battle did start, Mitscher would enjoy a two to one advantage in aircraft. Rather than Mitscher sailing into a trap, it was Ozawa who was sailing into one.

Following the American defeat at Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the U.S. Navy had moved decisively toward establishing the world’s first carrier-centered navy, a force that would play a deciding part in the Allied victory at Midway in June 1942.

In revenge for the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, U.S. carrier aircraft struck back in the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway. The Japanese failure to win a decisive victory in the Coral Sea, coupled with their loss at Midway, only strengthened the Japanese dependence on the strategy of a defensive decisive victory.

Meanwhile at Midway, Spruance, who had no earlier experience with carrier-launched aircraft battles, commanded Task Force 16, including the carriers Enterprise and Mitscher’s Hornet. Despite his inexperience, he was able to oversee an American victory, which included the sinking of four Japanese carriers.

The Americans leapfrogged their way steadily north through the Pacific, and the Japanese worked to build up their navy, waiting and watching for an opportunity for kantai kessen, the battle they believed would lead to the destruction of American naval power and decide the rest of the war. That opportunity, they would finally decide, had come in June 1944 in the Philippine Sea.

By 1944, however, the Japanese high command feared its ability to fight and win such a kantai kessen battle was slipping away. Imperial Navy aircrews had suffered serious losses, especially of skilled pilots at Coral Sea, Midway, and during the Solomon Islands campaigns. These were losses they could not easily replace, while the United States could easily replace its losses.

By the summer of 1944, the Americans had worked their way north sufficiently that they were preparing to invade the Mariana Islands. The Marianas, situated 700 miles south of the Japanese home islands, controlled the sea lanes to Japan. The capture of the islands would give the United States control of these sea lanes and would also put the U.S. Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers within striking distance of the Japanese home islands. Japan had to prevent the loss of the Marianas and stop the American advance north.

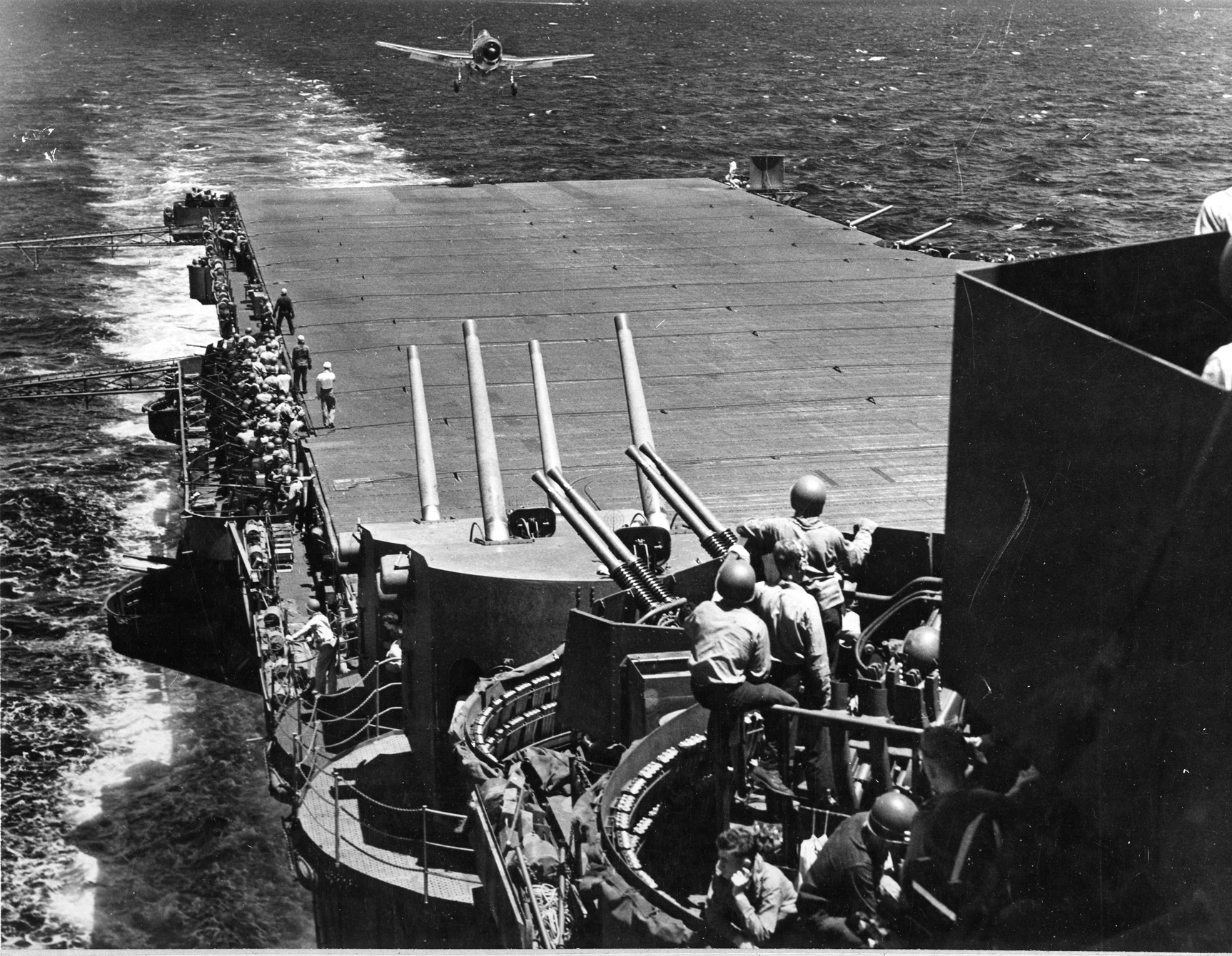

Still looking for the decisive victory that might end the war in the Pacific, the Japanese began eyeing Mitscher’s Task Force 58. The task force comprised five attack groups, each composed of three or four carriers and supporting ships. The ships of each attack group sailed in a circle formation with the carriers in the center and the supporting ships sailing close to the carriers so they could add their antiaircraft fire to that of the carriers and help ward off any attacking aircraft. When under attack by torpedo aircraft, the task group would turn toward the oncoming aircraft to limit attack angles. In addition, the carriers would not take evasive action when under attack, which allowed more stable platforms for the antiaircraft fire of all the ships in the task group. Mitscher had introduced many of these tactics.

In June 1944, Task Force 58 was part of Spruance’s 5th Fleet. The ships at sea were designated Task Force 58 under Spruance and Task Force 38 under Admiral William Halsey. The six-month name changes and apparent shifting of personnel in this two-platoon system had some benefit in confusing the Japanese, who at times were unsure as to the actual size of the American force.

Admiral Mineichi Koga, commander of the Combined Japanese Fleet, had been killed in March 1944 when his plane crashed in a typhoon. He was replaced with Admiral Soemu Toyoda, a torpedo and naval artillery expert who had been opposed to war with the United States, a war he had considered unwinnable. Despite this belief, Toyoda continued to develop the attack plans that Koga had been working on, plans aimed at a decisive victory.

On June 11, Mitscher’s carriers launched their first air strikes on the Marianas, and Toyoda became aware that the showdown in the Central Pacific was at hand. Japan had to save Saipan, and the only possible defense, he believed, was to sink the U.S. 5th Fleet that was covering the landing.

The Japanese fleet Ozawa commanded consisted of three large carriers (Taiho, Shokaku, and Zuikaku), two converted carriers (Junyo and Hiyo), and four light carriers (Ryuho, Chitose, Chiyoda, and Zuiho). Ozawa’s fleet also included five battleships (Yamato, Musashi, Kongo, Haruna, and Nagato), 13 heavy cruisers, six light cruisers, 27 destroyers, six oilers, and 24 submarines. Ozawa commanded from aboard the Taiho, which was the first Japanese carrier to have been built with an armor-plated flight deck, which was designed to withstand bomb hits.

The commanders in the U.S. 5th Fleet had 956 carrier-based planes available to them. In addition, Ozawa’a pilots only had about 25 percent of the training and experience the American pilots had, and he was working with inferior equipment. His ships had antiaircraft guns, for example, but lacked the new proximity fuses, which provided a more sophisticated triggering mechanism than the common contact fuses or timed fuses did, as well as good radar.

The Japanese fleet rendezvoused June 16 in the western part of the Philippine Sea. Japanese aircraft did have a superior range at that time, though, which allowed them to engage the American carriers beyond the range of American aircraft. They could attack at 300 miles and could search a radius of 560 miles, while the American Hellcat fighters were limited to an attack range of 200 miles and a search range of 325 miles. Additionally, with their island bases in the area, the Japanese believed their aircraft could attack the U.S. fleet and then land on the island airfields. They could thus shuttle between the islands and the attack, and the U.S. fleet would be receiving punishment with only a limited ability to respond.

The American air raids on the Marianas continued through June 15, and U.S. ships began an additional bombardment of the islands. On June 15, three divisions of American troops, two Marine divisions and one Army division, went ashore on Saipan, and Toyoda committed nearly the entire Japanese Navy to a counterattack. Toyoda wired Ozawa that he was to attack the Americans and annihilate their fleet. “The rise and fall of Imperial Japan depends on this one battle,” Toyoda wrote.

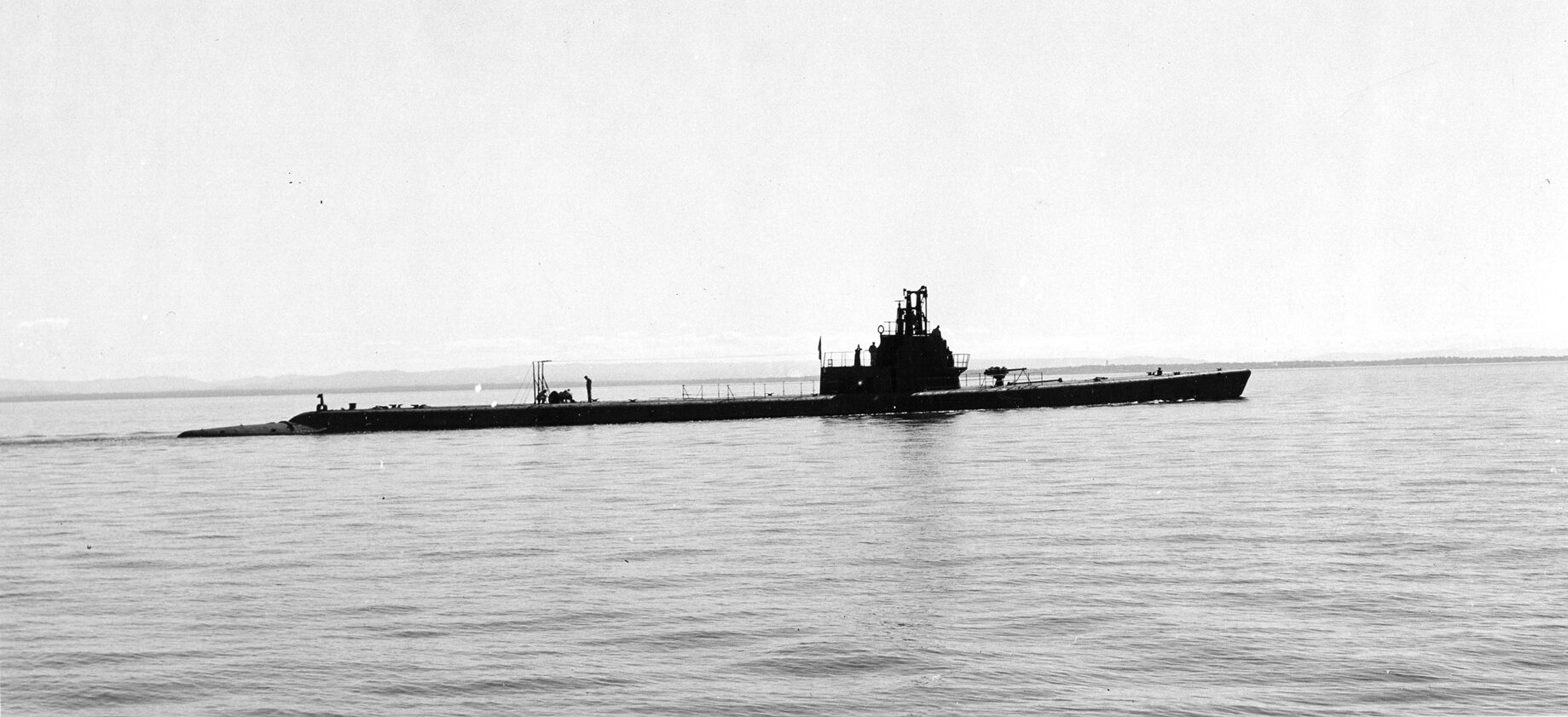

The U.S. submarines Flying Fish and Seahorse sighted the Japanese fleet near the Philippines on June 15. The Japanese ships did not finish refueling until two days later. Based on those sightings, Spruance quickly decided a major battle was at hand. He ordered Mitscher’s Task Force 58, which had sent two of its carrier task groups north to intercept aircraft reinforcements from Japan, to reform and move west of Saipan into the Philippine Sea. Mitscher was aboard his flagship, the carrier Lexington, which Tokyo Rose would erroneously report on at least two occasions to have been sunk. Spruance was aboard the heavy cruiser Indianapolis.

Task Force 58 comprised five attack groups. Deployed in front of the carriers to act as an antiaircraft screen was the battle group of Vice Admiral Willis Lee (Task Group 58.7), which contained seven battleships (Lee’s flagship the Washington, as well as the North Carolina, Indiana, Iowa, New Jersey, South Dakota, and Alabama), and eight heavy cruisers (Baltimore, Boston, Canberra, Wichita, Minneapolis, New Orleans, San Francisco, and Spruance’s Indianapolis). Just north of them was the weakest of the carrier groups, Rear Admiral William K. Harrill’s Task Group 58.4. This group was composed of only one fleet carrier (Essex) and two light carriers (Langley and Cowpens).

To the east, in a line running north to south, were three additional attack groups, each containing two fleet carriers and two light carriers. This was Rear Admiral Joseph Clark’s Task Group 58.1, which consisted of the Hornet, Yorktown, Belleau Wood, and Bataan, Rear Admiral Alfred Montgomery’s Task Group 58.2 (Bunker Hill, Wasp, Cabot, and Monterey), and Rear Admiral John W. Reeves’s Task Group 58.3 (Enterprise, Lexington, San Jacinto, and Princeton). These ships were supported by 13 light cruisers, 58 destroyers, and 28 submarines. The attack groups were deployed 12 to 15 miles apart.

Eight older battleships along with smaller escort carriers under the command of Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf remained near Saipan to protect the invasion fleet and provide air support for the landings.

On the afternoon of June 18, search planes sent out from the Japanese fleet located the American task force, and Rear Admiral Sueo Obayashi, commander of three of the Japanese carriers, immediately launched fighters. He quickly received a message from Ozawa, however, recalling the fighters. “Let’s do it properly tomorrow,” Ozawa wrote.

Later that night, the Americans also detected the Japanese ships moving toward them. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander of the Pacific Fleet, alerted Spruance that a Japanese vessel had broken radio silence and a message apparently sent by Ozawa to his land-based air forces on Guam had been intercepted. A fix obtained on that message placed the Japanese some 355 miles west-southwest of Task Force 58. Mitscher requested permission from Spruance to move Task Force 58 west during the night, which would by dawn put it in position to attack the approaching Japanese fleet. “We knew we were going to have hell slugged out of us in the morning [and] we knew we couldn’t reach them,” Captain Arleigh Burke, a member of Mitscher’s staff, said later when discussing that request.

But after considerable consideration, Spruance denied Mitscher permission to make the move. “If we were doing something so important that we were attracting the enemy to us, we could afford to let him come and take care of him when he arrived,” Spruance said.

This decision was far different from decisions Spruance had made at Midway. There he had advocated immediately attacking the enemy even before his own strike force was fully assembled with the intent of neutralizing the Japanese carriers before they could launch their planes, an action that he then considered the key to the survival of his carriers. He would also take considerable criticism for missing what some were to consider a chance to destroy the Japanese fleet.

Spruance’s decision to deny Mitscher’s request was influenced by orders from Nimitz, who had made it clear that the protection of the Marianas invasion was the primary mission of Task Force 58.

Spruance was concerned that the Japanese move could be an attempt to draw his ships away from the Marianas so a Japanese attack force could then slip behind it, overwhelm Oldendorf’s force, and destroy the landing fleet. Locating and destroying the Japanese fleet was not his primary objective, and he was unwilling to allow the main strike force of the Pacific Fleet to be drawn westward, away from the amphibious forces.

Spruance also may have been influenced by Japanese documents that had been captured in March and described just such a proposed plan: drawing American ships that were supporting an invasion away from an island and then sweeping in behind the fleet to destroy the invading force.

Spruance and Mitscher were different commanders. Though now commanding carriers, Spruance was still at heart a battleship man and, like most of the Imperial Japanese Navy establishment, he dreamed of a ship-to-ship confrontation. As the Battle of the Philippine Sea loomed, Spruance early on considered sending his fast battleships out to confront Ozawa in a night action and had only dropped the idea when his battleship commander, Admiral Lee, deferred. Lee had seen enough of night actions at Guadalcanal and the Solomons.

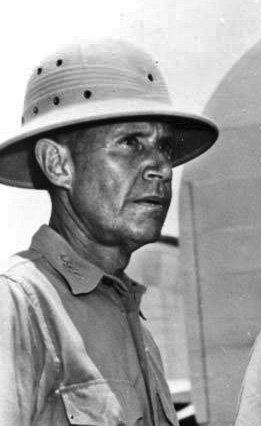

As for Mitscher, he was a carrier man. He sat on the bridge of his flagship watching the flight deck as planes were launched and could be seen using body language to help them off. He had graduated from the Naval Academy in 1910 and had taken an early interest in aviation, requesting a transfer to aeronautics in his last year as a midshipman. The request was denied, and he served on the destroyers Whipple and Stewart before being stationed on the armored cruiser North Carolina, which was being used as an experimental launching platform for aircraft. Mitscher trained as a pilot and became one of the first U.S. naval aviators on June 2, 1916.

As information about the Japanese buildup came in and the upcoming battle loomed, Mitscher said that what was coming “might be a hell of a battle for a while,” but added that he believed the task force could win it.

At dawn on June 18, Task Force 58 launched search aircraft, combat air patrols, and antisubmarine patrols and then turned the fleet west to gain maneuvering room away from the islands. The Japanese also launched search patrols early in the day. Those planes pinpointed the American position, and one of the Japanese planes, after locating the task force, attacked one of its destroyers. The attacking Japanese plane was shot down.

At dawn on June 19, Ozawa again launched search planes and located the American ships southwest of Saipan. He then launched 71 aircraft from his carriers, which were followed a short time later by another 128 planes.

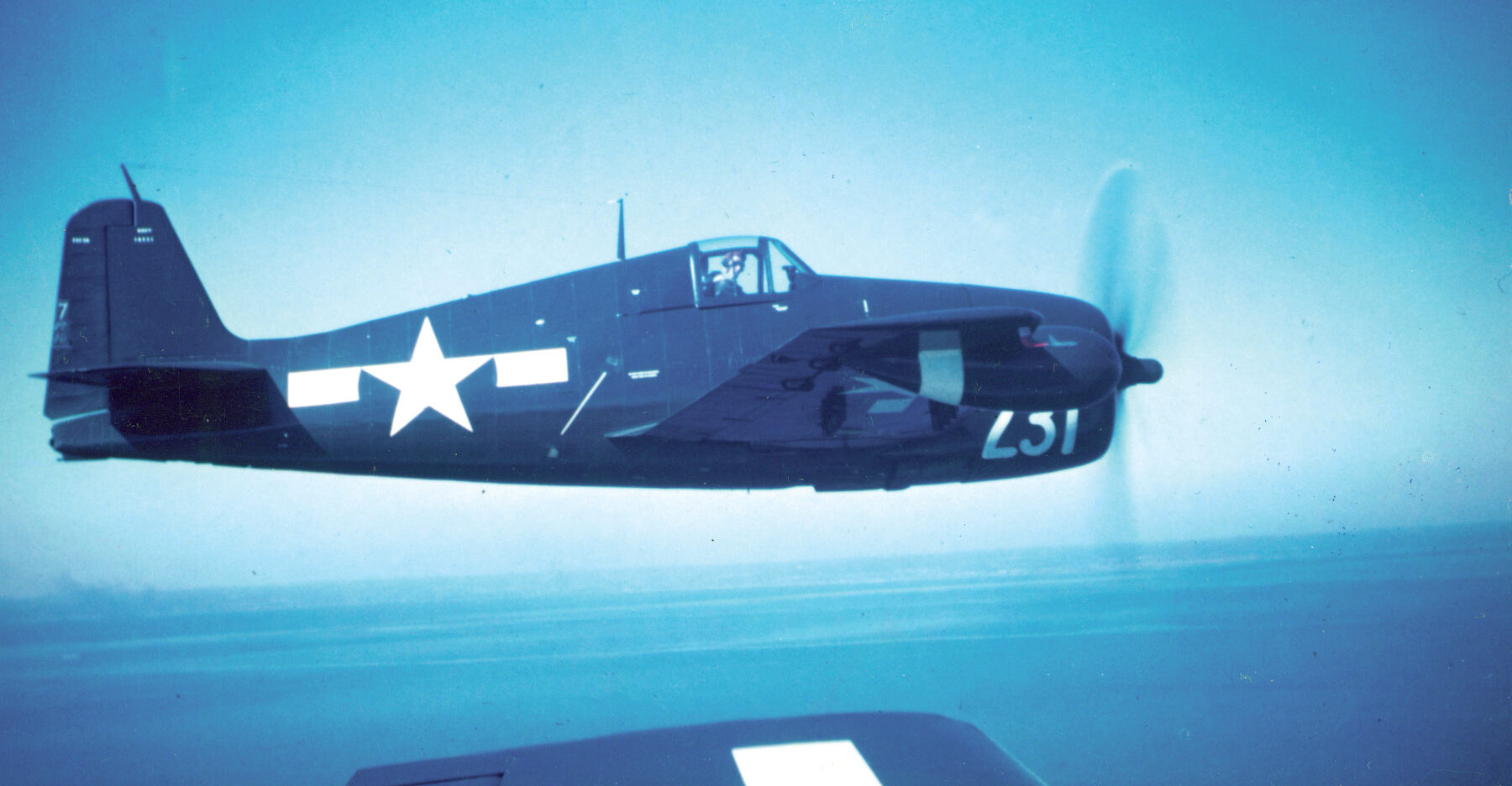

Among the U.S. fighters that would be sent up to confront them were a large number of F6F Hellcats, a Grumman aircraft that had been put into service in early 1942, eventually replacing the F4F Wildcat. The Hellcat had been engineered specifically to confront Japanese fighters when the Americans recovered an intact Zero during the fighting in the Aleutian Islands in 1942 and were able to engineer a fighter to succeed against it in combat. The Hellcat could outclimb and outdrive the Japanese Zero and was heavily armed. In addition, its pilot was protected by heavy armor plating, self-sealing fuel tanks, and a bulletproof windshield, which made it popular with the Navy pilots.

The American pilots who would meet the Japanese also had at least two years of training and 300 hours of flying experience as opposed to the Japanese pilots, who had at most six months of training and a few flying hours. They were faint copies of the pilots who had flown against the American base at Pearl Harbor and the American fleet at Midway.

At 10 am, radar aboard the American ships picked up the first wave of Japanese attackers. American fighters that had been sent to raid Guam were called back to the fleet, and at 10:23 am Mitscher ordered Task Force 58 to turn into the wind. All available fighters were sent up to await the Japanese. He then put his bomber aircraft aloft to orbit open waters to the east to avoid the danger of a Japanese bomb strike into a hangar deck full of aircraft.

The approaching Japanese planes were first spotted by a group of 12 Hellcats from the Belleau Wood about 72 miles out from the American fleet where they had paused to regroup. The Belleau Wood planes tore into the Japanese planes there and were soon joined by other American fighter groups. Twenty-five of the Japanese planes were quickly knocked out of the sky, and then 16 more.

As the Japanese and American fighters dove at each other, machine guns blazing, 70 miles west of the American fleet, a few of the Japanese planes were able to break away and work their way through to the American ships. They attacked the picket destroyers Yarnall and Stockham, causing only a small amount of damage. But one Japanese bomber was able to get through the American defenses and scored a direct hit on the main deck of the battleship South Dakota. More than 50 of her crew were killed or injured, but the ship remained operational.

Only one Hellcat was lost in the fighting. At 11:07 am, radar detected a second wave of 107 Japanese aircraft approaching. American fighters met this attacking group while it was still 60 miles out, and 70 of the attackers were shot down before they reached the task force. Of those that did get through, six attacked the American fleet, nearly hitting two of the carriers and causing some casualties before four of that six were brought down. A small group of torpedo planes also attacked the carrier Enterprise and the light carrier Princeton, but all were shot down. Altogether, 97 of those 107 attacking Japanese aircraft were destroyed.

A third attack consisting of 47 Japanese aircraft came at the American ships at about 1 pm. Forty U.S. fighters intercepted the attack group 50 miles out and shot down seven of the Japanese planes. A few again broke through defenses to attack the American ships but caused little or no damage. The 40 remaining Japanese aircraft fled the scene.

The Japanese fleet had also launched an additional attack, but somehow those planes had been given incorrect coordinates for the location of the American fleet and were originally unable to find the ships. Eighteen of those aircraft did finally stumble on some of the American ships as they were heading back to Guam and attacked. U.S. fighters shot down half of them while the remaining planes were able to attack the Wasp and Bunker Hill but failed to score any hits. Eight of these Japanese planes were also shot down. Meanwhile, the remains of this aborted attack force were intercepted by 27 American Hellcats as they were landing on Guam and 30 more were shot down. Nineteen others were damaged beyond repair.

“Hell, this is like an old-time turkey shoot,” said Lexington Commander Paul Buie, creating the nickname, “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot,” which would later be pinned on the battle by the men who were fighting it.

The Japanese had lost 346 aircraft during the day’s fighting, while the Americans had lost 15 and, aside from the casualties on the South Dakota, had suffered only minor damage to their ships.

The pilot with the highest score of the day was Captain David McCampbell of the Essex, who would go on to become the U.S. Navy ’s all-time leading ace with 34 confirmed kills during the war and would win the Medal of Honor for his actions in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. On June 19, he had downed five Japanese D4Y “Judy” carrier-based dive bombers. He would also notch two Zero fighters later in the day during an afternoon strike on Guam.

Lieutenant Alex Vraciu of the Lexington, the top-ranked Navy ace at the time with 12 victories, downed six Judys of the second wave in about eight minutes, and Ensign Wilbur “Spider” Webb, a recent transfer to fighters from bombers, attacked a flight of Aichi dive bombers over Guam, also downing six. Webb returned safely to the carrier Hornet, but the gunners aboard the Japanese bombers had shot his plane so full of holes that it was judged a total loss.

The destruction wrought in the air was not the only damage done to the Japanese that day. While the air battle was taking place, another battle was being fought above and below the surface of the sea.

At 8 am that day the submarine Albacore sighted a Japanese carrier group and began maneuvering to attack. The submarine’s commander, Lt. Cmdr. James W. Blanchard, selected the closest carrier to his position as his target. That carrier happened to be Admiral Ozawa’s flagship, the Taiho, the newest carrier in the Japanese fleet. As Blanchard gained position and prepared to fire, however, the Albacore’s fire-control computer failed, and he was forced to fire manually. Blanchard fired all six torpedoes in a single spread. Four veered off target. One of the remaining two was spotted heading for the Taiho by Japanese Warrant Officer Akio Komatsu, who had just taken off from the carrier. Without hesitation, Komatsu jammed his stick and intentionally dove his plane in front of the torpedo, detonating it and saving the carrier. But the remaining torpedo of the six struck the Taiho on its starboard side, rupturing two aviation fuel tanks. The Albacore was able to escape the ensuing depth charge attack with only minor damage.

Initially, the Taiho seemed to have suffered only slight damage, but gasoline vapors from the damaged fuel tanks soon began to leak into the hangar decks, creating a serious situation on the ship.

Meanwhile, a second American submarine, the Cavalla, attacked the carrier Shokaku, which was a veteran of the fighting at Pearl Harbor and the Coral Sea. At about noon, the Cavalla fired on the Japanese ship, hitting her with three torpedoes and badly damaging her. One torpedo had hit the forward aviation fuel tanks, and aircraft that had just landed and were being refueled exploded into flames. Ammunition, exploding bombs, and burning fuel added to the chaos. The order to abandon Shokaku had just been given when an explosion on her hangar deck initiated a series of secondary explosions that blew the ship apart. She rolled on her side and sank taking 887 officers and sailors and 376 members of the 601st Naval Air Group to the bottom with her. There were 570 survivors, including the carrier’s commanding officer, Captain Hiroshi Matsubara.

The destroyer Urakaze made several attempts to destroy the submarine, but the Cavalla escaped with relatively minor damage. However, she did get a scare. Cavalla’s main induction line, which brought air into the engines when she was on the surface, had become flooded during the initial depth charge attack, which made the submarine very heavy. When diving to avoid the attack of the Urakaze, the additional weight took Cavalla nearly 100 feet below her maximum test depth. “We hoped the safety factor would keep the hull from imploding,” said a crewmember. It did.

Three destroyers continued to hunt the Cavalla, dropping 106 depth charges, but she was able to slip away. Meanwhile, aboard the Taiho an inexperienced damage control officer ordered that the ship’s ventilation system be operated at full blast to clear the growing fumes. Instead of clearing the air, however, the action allowed the gasoline vapors to spread throughout the ship. At about 2:30 am, those fumes were ignited by an electric generator on the hangar deck, and a series of large explosions followed. Taiho had become a floating bomb. Ozawa and his staff quickly transferred to the nearby Zuikaku, and shortly afterward the Taiho sank, taking down 1,650 of her 2,150 officers and sailors.

As darkness fell, Ozawa retired to the northwest to refuel, intending to attack again in the morning. He had received several erroneous reports of heavy damage done to the American ships and was also under the impression that many of his missing aircraft had landed in the Marianas. During the night Task Force 58 began to move west in order to be closer to the Japanese when dawn came.

As the sun finally edged over the horizon, American search planes were sent out but were unable to locate the enemy. A later search also failed to make contact. But, finally, at 3:40 pm an American search plane located the Japanese fleet 275 miles away from the task force, near the limit of the American fighters’ range. That range was advertised at 250 miles, one aviation commander said, “But with planning and luck we could get to 300.” In addition, because of the time of day that the Japanese ships had been finally spotted, any planes that took off from the American carriers would have to strike in the fading light of dusk and find their way back to the American carriers and land in the dark, something that was new to most of the American pilots. Mitscher, prodded by Nimitz in Hawaii, nonetheless opted to launch an all-out attack.

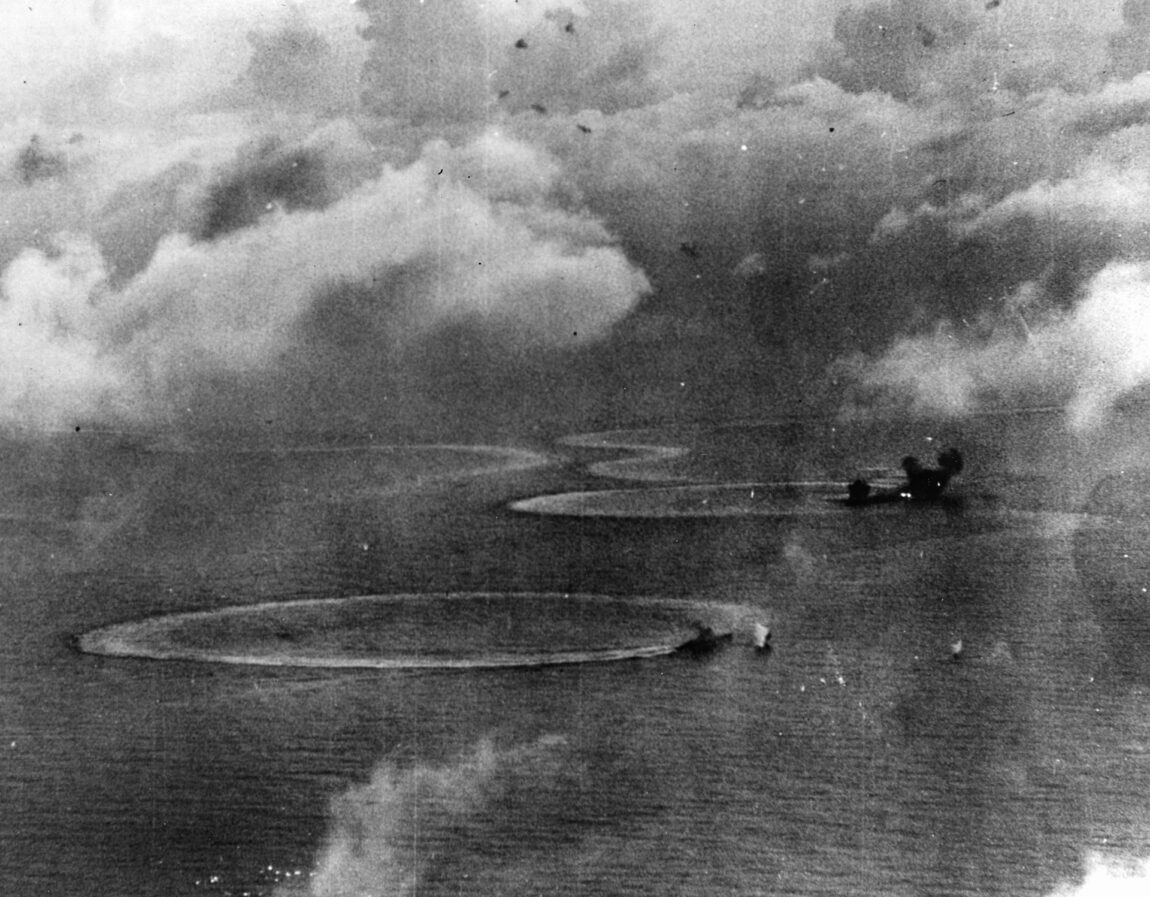

When he became aware of the American attack, Ozawa began pulling his ships back, hoping to get them out of the American planes’ range before they could close the gap. Aboard the American ships, a another message, perhaps a result of Ozawa’s retreat, arrived indicating the Japanese fleet was actually 60 miles farther out than previously believed. That put the Japanese at 335 miles, beyond even the Americans’ lucky range of 300 miles. Based on that information, further launches were cancelled, but the planes already launched were allowed to continue. Of these 240 planes, 14 returned to their carriers for various reasons. Of the remaining 226 planes, 95 were Hellcat fighters, 54 were Avenger torpedo bombers (only a few carrying torpedoes, the rest four 500-pound bombs), and 76 were Curtiss Helldivers and Douglas Dauntless dive bombers.

As the American planes approached the Japanese fleet, Ozawa was able to put up only 75 planes to protect his ships, and the American planes quickly overwhelmed these fighters. They swept through the Japanese defenses and attacked the fleet, quickly causing serious damage to several oilers and then hitting the carrier Hiyo, which was soon ablaze after leaking aviation fuel exploded. An abandon ship order was sounded, and she went down. Two hundred-fifty of the Hiyo crew were killed; Japanese destroyers in the area rescued the remaining 1,000 survivors.

Some of the American planes also bombed the large carrier Zuikaku and the light carrier Chiyoda, both of which were set ablaze, and heavily damaged the battleship Haruna and the heavy cruiser Maya. The converted carrier Junyo was also hit. Sixty-five Japanese planes were downed in the fighting as were 20 of the American aircraft. But for the Americans the worst was yet to come.

After the strike, which ended at about 6:45 pm, many of the American planes were already running low on fuel, and some had suffered enough battle damage that they were forced to ditch on their way back to their carriers. Darkness was falling. Despite the danger of submarine attacks on his ships, Mitscher fully illuminated his carriers and had his destroyers’ fire star shells to aid the pilots in landing.

“The effect on the pilots left behind was magnetic,” said Lt. Cmdr. Robert Winston. “They stood open-mouthed at the sheer audacity of asking the Japs to come and get us. Our pilots were not expendable.”

Sixty of the returning aircraft were still lost, many of them crashing into the sea as they ran out of fuel, but the majority of the flyers, 38 of the downed men, were eventually rescued.

Meanwhile, Admiral Ozawa received orders from Toyoda to cease fighting and withdraw from the area. U.S. forces briefly gave chase, but by June 21 the Japanese planes were out of range. The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot was over. As the Battle of the Philippine Sea loomed, Spruance early on considered sending his fast battleships out to confront Ozawa in a night action and had only dropped the idea when his battleship commander, Admiral Lee, deferred. Lee had seen enough of night actions at Guadalcanal and the Solomons.

As for Mitscher, he was a carrier man. He sat on the bridge of his flagship watching the flight deck as planes were launched and could be seen using body language to help them off. He had graduated from the Naval Academy in 1910 and had taken an early interest in aviation, requesting a transfer to aeronautics in his last year as a midshipman. The request was denied, and he served on the destroyers Whipple and Stewart before being stationed on the armored cruiser North Carolina, which was being used as an experimental launching platform for aircraft. Mitscher trained as a pilot and became one of the first U.S. naval aviators on June 2, 1916.

As information about the Japanese buildup came in and the upcoming battle loomed, Mitscher said that what was coming “might be a hell of a battle for a while,” but added that he believed the task force could win it.

At dawn on June 18, Task Force 58 launched search aircraft, combat air patrols, and antisubmarine patrols and then turned the fleet west to gain maneuvering room away from the islands. The Japanese also launched search patrols early in the day. Those planes pinpointed the American position, and one of the Japanese planes, after locating the task force, attacked one of its destroyers. The attacking Japanese plane was shot down.

At dawn on June 19, Ozawa again launched search planes and located the American ships southwest of Saipan. He then launched 71 aircraft from his carriers, which were followed a short time later by another 128 planes.

Among the U.S. fighters that would be sent up to confront them were a large number of F6F Hellcats, a Grumman aircraft that had been put into service in early 1942, eventually replacing the F4F Wildcat. The Hellcat had been engineered specifically to confront Japanese fighters when the Americans recovered an intact Zero during the fighting in the Aleutian Islands in 1942 and were able to engineer a fighter to succeed against it in combat. The Hellcat could outclimb and outdrive the Japanese Zero and was heavily armed. In addition, its pilot was protected by heavy armor plating, self-sealing fuel tanks, and a bulletproof windshield, which made it popular with the Navy pilots.

The American pilots who would meet the Japanese also had at least two years of training and 300 hours of flying experience as opposed to the Japanese pilots, who had at most six months of training and a few flying hours. They were faint copies of the pilots who had flown against the American base at Pearl Harbor and the American fleet at Midway.

At 10 am, radar aboard the American ships picked up the first wave of Japanese attackers. American fighters that had been sent to raid Guam were called back to the fleet, and at 10:23 am Mitscher ordered Task Force 58 to turn into the wind. All available fighters were sent up to await the Japanese. He then put his bomber aircraft aloft to orbit open waters to the east to avoid the danger of a Japanese bomb strike into a hangar deck full of aircraft.

The approaching Japanese planes were first spotted by a group of 12 Hellcats from the Belleau Wood about 72 miles out from the American fleet where they had paused to regroup. The Belleau Wood planes tore into the Japanese planes there and were soon joined by other American fighter groups. Twenty-five of the Japanese planes were quickly knocked out of the sky, and then 16 more.

As the Japanese and American fighters dove at each other, machine guns blazing, 70 miles west of the American fleet, a few of the Japanese planes were able to break away and work their way through to the American ships. They attacked the picket destroyers Yarnall and Stockham, causing only a small amount of damage. But one Japanese bomber was able to get through the American defenses and scored a direct hit on the main deck of the battleship South Dakota. More than 50 of her crew were killed or injured, but the ship remained operational.

Only one Hellcat was lost in the fighting. At 11:07 am, radar detected a second wave of 107 Japanese aircraft approaching. American fighters met this attacking group while it was still 60 miles out, and 70 of the attackers were shot down before they reached the task force. Of those that did get through, six attacked the American fleet, nearly hitting two of the carriers and causing some casualties before four of that six were brought down. A small group of torpedo planes also attacked the carrier Enterprise and the light carrier Princeton, but all were shot down. Altogether, 97 of those 107 attacking Japanese aircraft were destroyed.

A third attack consisting of 47 Japanese aircraft came at the American ships at about 1 pm. Forty U.S. fighters intercepted the attack group 50 miles out and shot down seven of the Japanese planes. A few again broke through defenses to attack the American ships but caused little or no damage. The 40 remaining Japanese aircraft fled the scene.

The Japanese fleet had also launched an additional attack, but somehow those planes had been given incorrect coordinates for the location of the American fleet and were originally unable to find the ships. Eighteen of those aircraft did finally stumble on some of the American ships as they were heading back to Guam and attacked. U.S. fighters shot down half of them while the remaining planes were able to attack the Wasp and Bunker Hill but failed to score any hits. Eight of these Japanese planes were also shot down. Meanwhile, the remains of this aborted attack force were intercepted by 27 American Hellcats as they were landing on Guam and 30 more were shot down. Nineteen others were damaged beyond repair.

“Hell, this is like an old-time turkey shoot,” said Lexington Commander Paul Buie, creating the nickname, “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot,” which would later be pinned on the battle by the men who were fighting it.

The Japanese had lost 346 aircraft during the day’s fighting, while the Americans had lost 15 and, aside from the casualties on the South Dakota, had suffered only minor damage to their ships.

The pilot with the highest score of the day was Captain David McCampbell of the Essex, who would go on to become the U.S. Navy ’s all-time leading ace with 34 confirmed kills during the war and would win the Medal of Honor for his actions in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. On June 19, he had downed five Japanese D4Y “Judy” carrier-based dive bombers. He would also notch two Zero fighters later in the day during an afternoon strike on Guam.

Lieutenant Alex Vraciu of the Lexington, the top-ranked Navy ace at the time with 12 victories, downed six Judys of the second wave in about eight minutes, and Ensign Wilbur “Spider” Webb, a recent transfer to fighters from bombers, attacked a flight of Aichi dive bombers over Guam, also downing six. Webb returned safely to the carrier Hornet, but the gunners aboard the Japanese bombers had shot his plane so full of holes that it was judged a total loss.

The destruction wrought in the air was not the only damage done to the Japanese that day. While the air battle was taking place, another battle was being fought above and below the surface of the sea.

At 8 am that day the submarine Albacore sighted a Japanese carrier group and began maneuvering to attack. The submarine’s commander, Lt. Cmdr. James W. Blanchard, selected the closest carrier to his position as his target. That carrier happened to be Admiral Ozawa’s flagship, the Taiho, the newest carrier in the Japanese fleet. As Blanchard gained position and prepared to fire, however, the Albacore’s fire-control computer failed, and he was forced to fire manually. Blanchard fired all six torpedoes in a single spread. Four veered off target. One of the remaining two was spotted heading for the Taiho by Japanese Warrant Officer Akio Komatsu, who had just taken off from the carrier. Without hesitation, Komatsu jammed his stick and intentionally dove his plane in front of the torpedo, detonating it and saving the carrier. But the remaining torpedo of the six struck the Taiho on its starboard side, rupturing two aviation fuel tanks. The Albacore was able to escape the ensuing depth charge attack with only minor damage.

Initially, the Taiho seemed to have suffered only slight damage, but gasoline vapors from the damaged fuel tanks soon began to leak into the hangar decks, creating a serious situation on the ship.

Meanwhile, a second American submarine, the Cavalla, attacked the carrier Shokaku, which was a veteran of the fighting at Pearl Harbor and the Coral Sea. At about noon, the Cavalla fired on the Japanese ship, hitting her with three torpedoes and badly damaging her. One torpedo had hit the forward aviation fuel tanks, and aircraft that had just landed and were being refueled exploded into flames. Ammunition, exploding bombs, and burning fuel added to the chaos. The order to abandon Shokaku had just been given when an explosion on her hangar deck initiated a series of secondary explosions that blew the ship apart. She rolled on her side and sank taking 887 officers and sailors and 376 members of the 601st Naval Air Group to the bottom with her. There were 570 survivors, including the carrier’s commanding officer, Captain Hiroshi Matsubara.

The destroyer Urakaze made several attempts to destroy the submarine, but the Cavalla escaped with relatively minor damage. However, she did get a scare. Cavalla’s main induction line, which brought air into the engines when she was on the surface, had become flooded during the initial depth charge attack, which made the submarine very heavy. When diving to avoid the attack of the Urakaze, the additional weight took Cavalla nearly 100 feet below her maximum test depth. “We hoped the safety factor would keep the hull from imploding,” said a crewmember. It did.

Three destroyers continued to hunt the Cavalla, dropping 106 depth charges, but she was able to slip away. Meanwhile, aboard the Taiho an inexperienced damage control officer ordered that the ship’s ventilation system be operated at full blast to clear the growing fumes. Instead of clearing the air, however, the action allowed the gasoline vapors to spread throughout the ship. At about 2:30 am, those fumes were ignited by an electric generator on the hangar deck, and a series of large explosions followed. Taiho had become a floating bomb. Ozawa and his staff quickly transferred to the nearby Zuikaku, and shortly afterward the Taiho sank, taking down 1,650 of her 2,150 officers and sailors.

As darkness fell, Ozawa retired to the northwest to refuel, intending to attack again in the morning. He had received several erroneous reports of heavy damage done to the American ships and was also under the impression that many of his missing aircraft had landed in the Marianas. During the night Task Force 58 began to move west in order to be closer to the Japanese when dawn came.

As the sun finally edged over the horizon, American search planes were sent out but were unable to locate the enemy. A later search also failed to make contact. But, finally, at 3:40 pm an American search plane located the Japanese fleet 275 miles away from the task force, near the limit of the American fighters’ range. That range was advertised at 250 miles, one aviation commander said, “But with planning and luck we could get to 300.” In addition, because of the time of day that the Japanese ships had been finally spotted, any planes that took off from the American carriers would have to strike in the fading light of dusk and find their way back to the American carriers and land in the dark, something that was new to most of the American pilots. Mitscher, prodded by Nimitz in Hawaii, nonetheless opted to launch an all-out attack.

When he became aware of the American attack, Ozawa began pulling his ships back, hoping to get them out of the American planes’ range before they could close the gap. Aboard the American ships, a another message, perhaps a result of Ozawa’s retreat, arrived indicating the Japanese fleet was actually 60 miles farther out than previously believed. That put the Japanese at 335 miles, beyond even the Americans’ lucky range of 300 miles. Based on that information, further launches were cancelled, but the planes already launched were allowed to continue. Of these 240 planes, 14 returned to their carriers for various reasons. Of the remaining 226 planes, 95 were Hellcat fighters, 54 were Avenger torpedo bombers (only a few carrying torpedoes, the rest four 500-pound bombs), and 76 were Curtiss Helldivers and Douglas Dauntless dive bombers.

As the American planes approached the Japanese fleet, Ozawa was able to put up only 75 planes to protect his ships, and the American planes quickly overwhelmed these fighters. They swept through the Japanese defenses and attacked the fleet, quickly causing serious damage to several oilers and then hitting the carrier Hiyo, which was soon ablaze after leaking aviation fuel exploded. An abandon ship order was sounded, and she went down. Two hundred-fifty of the Hiyo crew were killed; Japanese destroyers in the area rescued the remaining 1,000 survivors.

Some of the American planes also bombed the large carrier Zuikaku and the light carrier Chiyoda, both of which were set ablaze, and heavily damaged the battleship Haruna and the heavy cruiser Maya. The converted carrier Junyo was also hit. Sixty-five Japanese planes were downed in the fighting as were 20 of the American aircraft. But for the Americans the worst was yet

to come. After the strike, which ended at about 6:45 pm, many of the American planes were already running low on fuel, and some had suffered enough battle damage that they were forced to ditch on their way back to their carriers. Darkness was falling. Despite the danger of submarine attacks on his ships, Mitscher fully illuminated his carriers and had his destroyers’ fire star shells to aid the pilots in landing.

“The effect on the pilots left behind was magnetic,” said Lt. Cmdr. Robert Winston. “They stood open-mouthed at the sheer audacity of asking the Japs to come and get us. Our pilots were not expendable.”

Sixty of the returning aircraft were still lost, many of them crashing into the sea as they ran out of fuel, but the majority of the flyers, 38 of the downed men, were eventually rescued.

Meanwhile, Admiral Ozawa received orders from Toyoda to cease fighting and withdraw from the area. U.S. forces briefly gave chase, but by June 21 the Japanese planes were out of range. The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot was over.

The Battle of the Philippine Sea had been a resounding American victory. The Japanese lost three carriers and two oilers sunk and had almost all of their aircraft destroyed. Six other ships had been damaged and an estimated 2,987 Japanese combatants killed. The Americans had one battleship damaged and 123 aircraft destroyed. The task force lost 29 airmen and another 31 men on the ships.

The Japanese losses were irreplaceable. They had spent the better part of a year building up their carrier strike force, and the United States had destroyed 90 percent of it in the fighting. The Japanese only had enough pilots left to form the air group for one of their light carriers, and during the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944 they used their carriers only as decoys.

The battle also added to the growing reputation of the American F6F Hellcat. With its powerful engine, greater speed, and firepower it had proved itself deadly, greatly outclassing the A6M Zero.

Spruance’s conservative battle plan, while not destroying all of the Japanese aircraft carriers, had resulted in an overwhelming American victory. It had severely weakened Japanese naval aviation forces by killing most of the remaining trained enemy pilots and destroying their last reserves of naval aircraft. Despite the lopsided American victory, though, many officers, particularly aviators, criticized Spruance for his decision to fight the battle cautiously rather than exploit his superior forces and intelligence more aggressively.

Spruance’s critics argued that he had squandered an opportunity to destroy the entire Japanese fleet. Admiral John Towers, a naval aviation pioneer and deputy commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, demanded that Spruance be relieved. The request was denied by Nimitz. Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, commander of the amphibious force during the Pacific campaign, and the Navy’s most senior commander, Admiral Ernest King, chief of naval operations, joined Nimitz in supporting Spruance. Despite what some called the chance of the century, Spruance had done what Nimitz had ordered him to do: he had remained and protected the invasion of Saipan.

A month after the Battle of the Philippine Sea, King and Nimitz visited Spruance at Saipan. During that meeting, King made a point of telling Spruance of his support. “You did a damn fine job there,” he said. “No matter what other people tell you, your decision was correct.”

The Battle of the Philippine Sea was the last great contest between carrier strike forces ever fought. It was a victory that, among other things, brought the American B-29 within striking distance of the Japanese home islands, and in so doing shortened the war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments