By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

In 941 ad, in the fortress of Kincora overlooking the River Shannon just south of Lake Derg, Queen Be Bhionn gave birth to a son, Brian Mac Cennétig. Brian’s father, Cennétig mac Lorcain, was a petty king of the Dal Cais clan of the district of Thomond, north of Munster. To the south of Kincora, another of King Cennétig’s fortresses, Béal Boruma, guarded a river ford. There the Dalcassians paid cattle tribute to the powerful Munster clan, the Eoganacht. It was from the name of the ford that the newborn received his surname Boru (tributes), a fitting moniker for one destined to receive the tribute of all Ireland in his time.

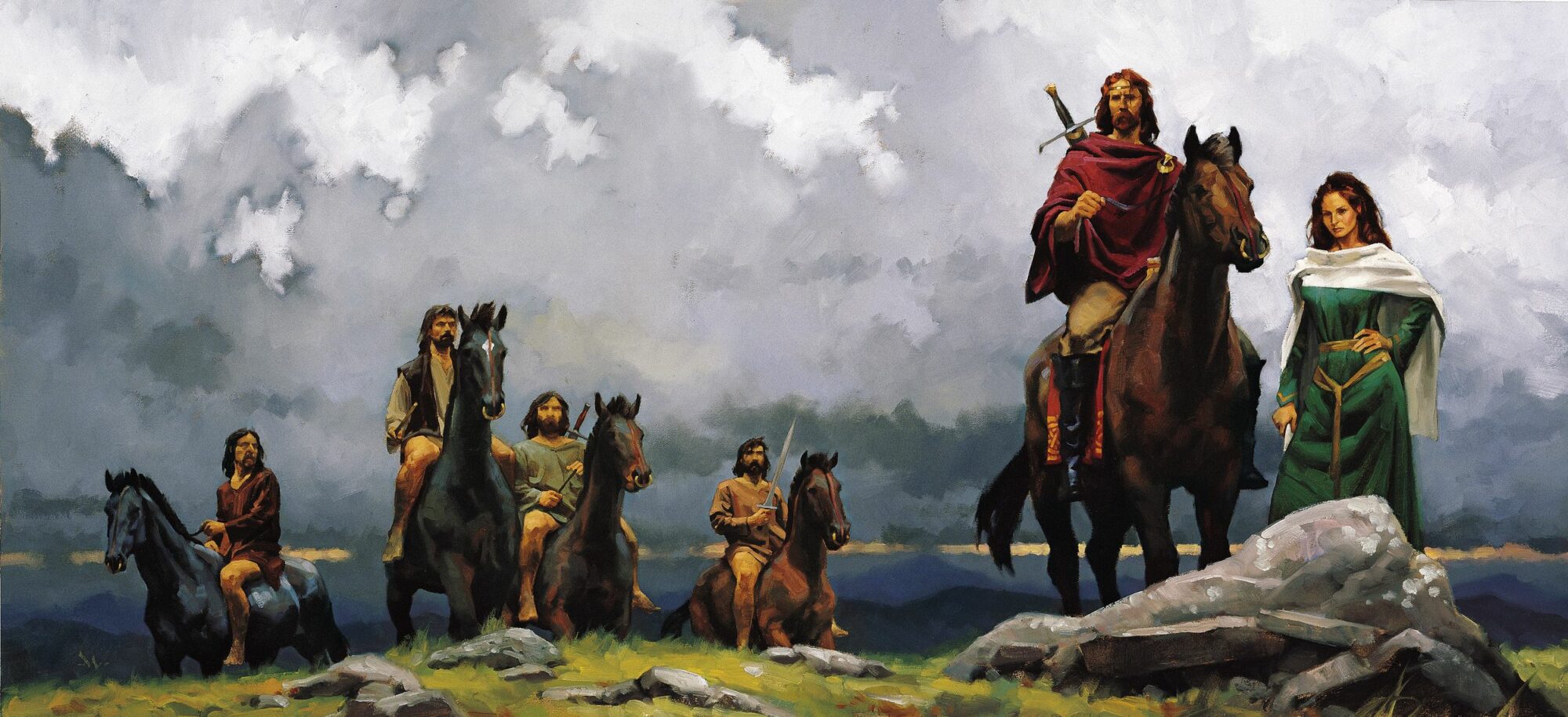

The Brains and Brawn of Brian Boru

As a child, Brian sat at the hearth in his father’s great hall, listening to tales of ancient Irish heroes. Thus inspired, Brian began to practice with the throwing spear as soon as he was old enough to walk. It would take more than martial skills, however, for him to become a great lord. Young Brian was sent to the monks of Inisfallen, in the lake lands of Killarney, for instruction in religious matters, science, and law. Ireland at that time was roughly divided into the regions of Ulster in the north, Connacht in the west, Meath in the middle, Leister in the east, and Munster in the south. Each region was dominated by a king and a major clan, but there were also numerous sub-kings and minor clans. Alliances were quickly made and unmade as the kings and clans constantly fought each other. Into this political cauldron were thrown the country’s longtime foreign occupiers, the Danes and Norwegians. First as Viking raiders, then as merchants and traders, the Norsemen had established coastal bases at Waterford, Wexford, Cork, Limerick, and above all at Dublin, the future capital of Ireland.

When Brian was 11, the Eoganacht allied themselves with the Danes to defeat the Dalcassians. The war claimed the lives of Brian’s father and mother. Four years later, the Danes not only attacked the Dalcassians again, but also turned on the Eoganacht. In Munster, the Eoganacht surrendered territory after territory. In Thomond, by contrast, the Dalcassians led by their new king, Brian’s brother Mathghamhain, refused to submit. The Danes drove the Dal Cais resistance farther and farther into the ancient forests and barren limestone uplands of the Clare wilderness. Brian, now 17, fought at his older brother’s side. It was during these troublesome times that Brian married the first of several wives, Mor, who bore him three sons.

Brian the Warrior

Viking ships pillaged up and down the Shannon’s shores at will, their Norse dragon ships pushing up waterways untried by the Irish. The ships’ shallow drafts, less than four feet, allowed the raiders to jump into the water and dash unexpectedly upon riverside villages. Defeat for the Dalcassians seemed inevitable until 962, when Osraighe, a tributary kingdom of Leinster, came to the rescue by inflicting a crushing defeat on the Norsemen. With his own forces worn out, Mathghamhain welcomed the opportunity to negotiate a temporary truce with the Vikings. Brian, however, could not forget his slain parents and opposed any sign of weakness. With only a hundred followers, he carried on the war. From hidden mountain caves and woodland strongholds, Brian and his guerrilla fighters ventured forth, weapons ready, light bags of provisions slung around their necks. At night they sneaked up on Norse outposts along the Shannon’s banks. At Brian’s signal, javelins swooshed without warning into the Norse guards. Brian and his men sprang forth, wielding their fearsome battle-axes and cleaving off whole limbs at one blow. Others drew their short swords for close-in combat, often using one in each hand. The tall Norsemen fought back fiercely, their powerful blades swinging in great arcs to slice through the hide and tanned-leather armor of the Dalcassians.

Brian’s ambushes so unnerved the Danes that there were rumors of a large Dalcassian army massing in the hills. Brian and his hungry little band paid a heavy price for their successes, finding themselves hunted incessantly through the chilling, wet winter. Brian’s followers were reduced to only 15 men, but still he did not give up. Mathghamhain, meanwhile, rebuilt his power and subdued the Eoganacht. Eventually, Brian’s unbroken spirit won Mathghamhain back to his side. In 964, the two brothers took the fight to the Danes in Limerick. There followed four years of war, culminating in the decisive Battle of Solchoid. The Irish held the higher ground and defended from behind the cover of low willow trees and shrubs. The Norsemen, under their leader Ivar, began their assault at sunrise, but the Irish lines refused to break. At midday, the Irish stormed down to slaughter their exhausted foes. Brian and Mathghamhain marched on Limerick in the dark. The city capitulated without resistance, and the Dalcassians butchered and burned without mercy. The spoils were plentiful, but Ivar escaped to the island of Inis Cathaigh.

Avenging the Death of his Brother

Solchoid paved the way for Mathghamhain’s inauguration as king of Munster in 970. The deposed Eoganacht smoldered with resentment and bided their time. Six years later, the Eoganacht king of Desmond, Maolmhuadh, ambushed Mathghamhain on a lonely mountain road and skewered his sword through Mathghamhain’s heart. When Brian heard of his brother’s death, he swore that Mathghamahain’s murderers “shall forfeit life for this deed, or I shall perish by a violent death.” First to feel Brian’s wrath was Ivar, whom Brian suspected had taken a hand in the murder. Ignoring the traditional sanctuary of St. Seanan on Inis Cathaigh, Brian killed Ivar in personal combat, then slaughtered two of his sons and looted his fortress and the surrounding islands. Brian killed two more of Maolmhuadh’s allies, the treacherous Donnabhan of Fhidhghinte and Harald, Ivar’s third son and the reigning king of Limerick. Limerick was sacked again amid much killing and looting. Maolmhuadh’s end came with his defeat at the 978 Battle of Bealach Leacht, after which he was tracked down and killed by Brian’s eldest son, Murchadh.

King of Munster

Brian rode to the seat of the kings of Munster at Cashel. Under the royal tree of Maigh Adhair, he took the white wand—the royal symbol of justice—in his hand, and the royal diadem was placed on his head. In an oath of obedience, the assembled nobles of Munster placed their hands between those of Brian. The beginning of his reign was filled with battles, plundering, ravaging, and general unquiet. To face such troublesome times, Brian consolidated his position among the defeated Eoganacht, making allies of his former foes by marrying his daughter to Cian, son of the late Maolmhuadh. The marriage was a wise diplomatic move on Brian’s part, for Cian proved to be an unwavering ally.

As king of Munster, Brian faced new and more dangerous rivals. Munster and the Danes of Limerick may have been subjugated, but to the north there were more Norse strongholds and other powerful Irish kings. In 979 Brian recorded victories over the Danes of Waterford and King Ua Faolain of the neighboring Decies clan. Brian then instigated war with Leinster by demanding an 800-year-old tribute that Leinster owed the king of Munster. When Leinster refused to swear allegiance to Munster or to pay the required 300 gold-handled swords, cows with brass yokes, horses, and cloaks, Brian invaded.

War with Maol-Seachlainn

Meanwhile, the new high king of Ireland, 32-year-old Maol-Seachlainn mac Domnall II, was determined to quash anyone who questioned his authority. In 983, before he defeated the rebellious forces of Leinster and Dublin, Maol-Seachlainn veered into Munster. To warn Brian to stay put in Munster, Maol-Seachlainn uprooted Maigh Adhair. Instead, Brian riposted with a raid into Maol-Seachlainn’s realm of Meath. For the next 15 years, Brian and Maol-Seachlainn were at odds with each other. Evenly matched, they at first avoided fixed battle, instead choosing to plunder each other’s lands and prey on neighboring Irish kingdoms and Viking settlements. In 988 Brian showed himself a true opportunist when he enlisted the help of his erstwhile enemies, the Vikings of Waterford, to inflict a devastating defeat upon the king of Connacht at Lough Ree. To establish ties with the defeated King Cathal, Brian took Cathal’s daughter Dubhchobhlaigh as his wife. In 992 and again in 994, Brian’s forces met Maol-Seachlainn’s army in battle, but Brian was routed each time.

In 998, Brian and Maol-Seachlainn concluded a peace treaty, and the following year they faced the alliance of King Sigtrygg Silkbeard Olafs- son of Dublin and King Maol Mórdha of Leinster. The fact that Maol Mórdha was also Sigtrygg’s uncle, while Sigtrygg himself was Maol-Seachlainn’s former stepson, showed just how closely tied the warring factions were. Sigtrygg hoped to engage Maol-Seachlainn and Brian in the open plains of Kildare, where his superior cavalry would give him the advantage, but he underestimated the speed of his foes. Brian and Maol-Seachlainn force-marched their men to intercept the Dublin-Leister army in the hills of Gleann Mama. Holding the higher ground, Brian and Maol-Seachlainn emerged victorious. Brian, not Maol-Seachlainn, claimed the battle honors, and Dublin subsequently submitted to Brian. For a week the city was sacked, yielding much gold, silver hangings, and other precious loot.

Murchadh dragged Maol Mórdha from hiding in a yew tree. Maol Mórdha’s life was spared and he was allowed to remain king of Leinster. Sigtrygg fared even better. Not only did Brian allow him to remain king of Dublin, but Brian gave him his daughter in marriage. Brian himself married the alluring Gormfhlaith, Sigtrygg’s mother and ex-wife of Maol-Seachlainn. Gormfhlaith became Brian’s fourth wife (he also had 30 concubines). Brian hoped that his generous treatment of the defeated king and his newly forged marriage bonds would ensure Sigtrygg’s loyalty in the future.

His victory at Gleann Mama showed the rest of Ireland that Brian’s star was on the rise while that of Maol-Seachlainn was on the wane. Brian immediately turned on Maol-Seachlainn and led a great host of chiefs and forces toward Tara, a stronghold that dated back to Neolithic times and was the traditional parliament of the high kings until the 6th century. Tara remained an easily defended military position, overlooking the plains of Meath. Sent ahead of his main army, Brian’s Norse cavalry prematurely clashed with Maol-Seachlainn’s army and was nearly wiped out. Brian ignobly withdrew. King Cathal of Connacht consequently rebelled against Brian, but a year later, in 1002, Brian defeated him once again. Brian struck for Tara and demanded the high throne. By now he had intimidated all the other Irish kings. None came to fight beside Maol-Seachlainn, not even Maol-Seachlainn’s own kinsmen, the northern Ui Neill clan of Ulster. Maol-Seachlainn had little choice but to yield. At Cashel, Brian took up the diadem of high king and emperor of the Gaels. Three quarters of Ireland was now under his control.

Maol Mórdha Rises Against Brian

To cow any potential challengers, Brian built fortresses, strengthened the fortifications of Cashel, took hostages, and sent Murchadh on punitive raids. Although Cashel was his capital, Brian preferred to rule from his boyhood home, Kincora. He was fortunate that his sons proved loyal and did not turn on each other—or on him. In the subjugated Norse towns, trade with Europe flourished in slaves, wine, walrus tusks, spices, furs, and silks. From Brian’s vassal kingdoms, a ceaseless tribute of cows, hogs, cloaks, iron, and wine flowed into Munster. Decades of raids by Vikings, by Irish lords, and even by Irish abbots had caused much damage to the land. Brian used his growing wealth to improve roads, build bridges, restore old churches and monasteries, and build new ones alongside schools. For nearly a decade, minor feuds aside, Ireland enjoyed untypical peace and a cultural renaissance.

Trouble brewed when Brian became estranged from Gormfhlaith, who left Kincora to return to Dublin. Consumed by hatred for Brian, she egged on her son, Sigtrygg, and King Maol Mórdha to rise against Brian. Brian responded with a severe new tribute that sent Leinster into near-starvation and summoned Maol Mórdha to Kincora for a show of obedience. Coaxed into an argument by Murchadh, Maol Mórdha stormed out of the castle before consulting with Brian. A messenger sent after him by Brian was later found with his skull smashed in.

Whether the threat was real or imagined, Maol Mórdha reforged his alliance with Sigtrygg. Maol-Seachlainn, however, stayed loyal to Brian. He even sent his army against Dublin, but suffered a crippling defeat. In 1013, Brian and Murchadh arrived to plunder Osraighe and southern Leinster before heading on to Dublin. Early in September, Sigtrygg watched as Brian and Murchadh’s army set up camp outside the city’s landward walls. This time, however, Sigtrygg wisely did not sally forth. The fortifications of the Viking strongholds were more formidable than those of the Irish forts and, when resolutely defended, were beyond Brian’s or any other Irish king’s power to overcome. After more than three months of blockade, Brian’s forces stirred with mutiny because supplies were running low and the foul winter weather was on the way. Sigtrygg jeered as Brian’s humbled army broke camp, but he knew that Brian would return. In search of allies, Sigtrygg set off to the hall of Sigurd Hlodvirsson the Stout, the Norse earl of the Orkneys. In return for bringing a few hundred half-heathen, half-Christian men as reinforcements, Sigurd demanded Gormfhlaith’s hand in marriage and an Irish kingdom to rule. Gormfhlaith was pleased with her son, but counseled Sigtrygg to gather an even greater force. He found more help in the pirates of the pagan Dane, Brodar of the Isle of Man. The cunning Sigtrygg promised Brodar the same reward he had promised Sigurd. Brodar and Sigtrygg reckoned that, at the comparatively advanced age of 54, Sigurd could well die in battle.

Preparing for Battle

In the coming conflict, Brian depended on his loyal Munster warriors, as well as the Danish stewards of Waterford and Limerick. Only a few reinforcements strode forth from Connacht, and none came from Ulster. Fortunately for Brian, Maol-Seachlainn promised to help, and a new ally was found in Brian’s son-in-law, King Malcolm II of Scotland, who sent a small force commanded by Domhnall, the great steward of Mar. It was also heartening to hear that southern Leinster had refused to aid Sigtrygg and Maol Mórdha. With his 5,000 warriors, Brian still held numerical superiority over Maol Mórdha and Sigtrygg, who barely commanded more than 3,000 Vikings and Irishmen between them. Nevertheless, Brian had to act quickly to wipe out Dublin’s and Leinster’s newfound independence before the neutral Irish kings could turn against him.

Brian’s youngest son, Donnach, took a few hundred men to keep an eye on southern Leinster. Brian set up his own camp north of Dublin on a hillock in the Wood of Tomar. From there he could see the city to the south, its harbor thick with Norse longboats, and between Brian’s camp and the city, the sprawling tents and campfires of his enemies. Maol Mórdha, Sigurd, Brodar, and Dubhgall, Sigtrygg’s brother, had set up their camps near the little fishing weir of Clontarf. Sigtrygg remained in Dublin with a reserve force.

On Thursday, April 22, 1014, Brian sat down to take council with his lords. Tempers flared, and as a result Maol-Seachlainn withdrew his forces to Meath. The hot-headed Murchad might well have been to blame. Brian now no longer held the numerical advantage. He immediately sent word for Donnach to hurry back, but there was little chance his son would arrive in time. Brian’s hair was now silver, and he was

73 years old. Too old to personally lead his warriors in battle, Brian would have to depend on Murchadh, who was unquestionably brave but also reckless. That night, Brian’s mind was haunted by worries. According to legend, a banshee visited Brian and warned him that he would fall in battle, and that “this plain shall be red tomorrow with your proud blood.” On the Viking side, Brodar, who was widely believed to be a sorcerer, prophesied that should they fight on Good Friday, Brian would die, but his army would be victorious. Whatever the truth behind such tales, Maol Mórdha, Sigtrygg, Sigurd, and Brodar all knew that they had to strike before Donnach returned.

Praying for Victory

Brian had lost none of his regal bearing as he reviewed his army at dawn of Good Friday. He looked to his brave Dalcassians, who Murchadh would use to spearhead the attack. Ready to fight beside Murchadh was his 15-year-old son, the crown prince Tordhelbach, and Murchadh’s brothers, Conchobhar and Flann. Behind them fluttered the banner of Brian’s nephew, Conaing, king of Desmond. Also present that day were the Eoganacht lords Cian and Domhnall, Domhnall, the great steward of Mar, King Tadhg of Connacht, and an array of lesser kings and princes. On his wings, Brian stationed his 10 Danish stewards and their troops.

Brian’s army followed Murchadh’s blue banner to meet the oncoming Dublin-Leinster coalition at Clontarf. The latter advanced with Sigurd and Brodar’s Vikings in the lead, followed by the Danes from Dublin and, behind them, Maol Mórdha and his Leinster men. Murchadh recklessly initiated the attack by bolting ahead of the main army. Alarmed, Brian called for him to fall back into line. Murchadh replied that he would not retreat one step backward. Inspired by Murchadh’s valor, the rest of Brian’s army surged forward. Meanwhile, Brian knelt down before his pavilion to pray for victory. Below him the two armies collided in a deafening crescendo of clashing arms and battle cries. From behind their large round shields, protected by leather and ring-mail byrnies, the Danes slashed and thrust their axes, spears, and swords. Their Irish foes lacked armor but not spirit, and fought back with unbridled fury. There were few lulls in the fighting.

Engulfed in a semicircle, the Dublin and Leinster men slowly gave way to Brian’s battle-crazed Irish and Danish troops. Although their army fled around them, Sigurd and his guard stood like an unbroken bastion, the legend-shrouded Raven banner of the Orkneys fluttering at Sigurd’s side. One Viking warrior after another took up the banner, only to be cut down again by Murchadh’s relentless assault. The last hands to grasp the fateful Raven banner were those of its lord. Sigurd wrapped the banner around himself before he was decapitated by Murchadh with two powerful blows to the neck. Scarcely had Murchadh caught his breath from slaying Sigurd than there appeared the fierce Norse champion, Amrud, who had carved a bloody path through the Dalcassians. Murchadh grappled Amrud to the ground and tore away his sword. Murchadh leaned the pommel of the sword against his own breast and drove it three times into Amrud, piercing the earth beneath him. Gurgling blood, Amrud plunged his own blade into Murchadh, killing him simultaneously.

Panicked Norsemen and Leinstermen threw themselves into the ocean, hoping to reach their longboats. Heedless of their own safety and hungry for blood, their pursuers followed them into the waves. The high tide carried both to their doom. His hands locked upon the hair of a Dane, Murchadh’s son Tordhelbach was washed upon the Weir of Clontarf. A stake shot through his body, and he drowned. The number of men killed on both sides was great. Conchobhar and Flann, King Tadhag of Connacht and Domhnall of the Eoganacht were among the 30 Irish chiefs and kings who died that day. Except for Sigtrygg and Brodar, all the Norse-Leinster leaders were slain among their annihilated army. Maol Mórdha and Conaing, king of Desmond, fell by each other’s hand.

From Dublin’s ramparts, the Danish women anxiously watched the battle. Brian’s proud daughter stood there too, and at sight of the Norsemen rout she mocked her husband Sigtrygg. “It appears that the foreigners have gained their their natural inheritance—the sea,” she scoffed. In anger, Sigtrygg hit her in the face, knocking out one of her teeth. Sigtrygg rode forth too late to rally his men and was lucky to flee back into Dublin alive.

“Now Let Man Tell Man That Brodar Felled Brian”

On the battlefield Brodar stood panting, the muscles of his tall and powerful frame exhausted and his long black locks thick with sweat. The cuts and dents in his splendid coat of mail and crimson axe bore silent witness to the havoc he had inflicted on the Irish. Only two of Brodar’s men remained at his side, and on a whim he decided to lead them not to the sea but northward instead. Brodar hoped to circumvent the battle and reach his ship in safety that night. His route led him to the Wood of Tomar and Brian Boru’s camp. Brian, grieving over his sons’ fallen standards, had given up all hope and was dictating his will to his only companion, a page boy. Finding Brian, Brodar could scarcely believe his luck. Below them the Norse and Leinster pavilions lit up the darkening sky in flame. Brodar caught his breath—now was his chance for revenge. As Brodar fell upon him, Brian barely managed to draw his sword and slash its blade across Brodar’s leg. Ignoring the wound, Brodar smashed his axe into Brian’s skull. With a spurt of blood, Brian fell dead, and Brodar cried out, “Now let man tell man that Brodar felled Brian.” A second blow of his axe struck down the hapless page boy. Brodar did not survive Brian’s assassination for long. Found hiding in the wood by Brian’s men, his belly was cut open and he was wrapped around the trunk of a tree by his entrails.

When Donnach arrived from southern Leinster on Easter Sunday, only Cian of the Eoganacht remained alive to tell him of his father’s death and those of his older brothers. Brian was buried in a marble coffin at Ireland’s chief church, St. Patrick’s at Armagh, and for 12 days masses were held for Brian and Murchadh throughout the country. The Battle of Clontarf was immortalized as a heroic feat of Irish arms and the doom of the Vikings in Ireland. In reality, although Clontarf ended any chance of Norse dominance over Ireland, neither the Norse lords nor their trade disappeared from Ireland after the battle. In Dublin, Sigtrygg managed to stay in power until his death in 1042.

Clontarf did, however, spell the end to the ascendancy of the Dalcassians. Without the leadership of Brian and Murchadh, the weakened Dalcassians were unable to maintain their hold on Ireland. Maol-Seachlainn became high king again but was too old and weak to build on Brian’s final success. For the next 150 years the Irish reverted to their old habit of infighting. When the Normans invaded in the 1160 ad, there was no second Brian to rally the tribes. Ireland fell to the invaders, and Scandinavian influence too dwindled away. Brian’s death ended his dream of a united Ireland, but the memory of Brian Boru, Ireland’s mightiest warrior-king, remains unforgotten and unforgettable.

Join The Conversation

Comments