By Patrick J. Chaisson

A Polish flag, followed minutes later by a Union Jack, appeared above the ruins of the abbey on the summit of Italy’s 17,000-foot Monte Cassino.

It was 9:45 a.m. on Thursday, May 18, 1944, and Allied troops all along the valley floor cheered in celebration. They had good cause to celebrate—the Poles’ victory on “Monastery Hill” signified an end to the bloody Battle of Cassino.

Throughout that awful winter and spring fighting men from the United Kingdom, Poland, New Zealand, Canada, India, South Africa, France, and the United States grappled with tenacious German defenders for possession of key terrain surrounding the town of Cassino in southern Italy. An estimated 55,000 Allied soldiers were killed or wounded during this five-month campaign, which concluded only when a patrol from the 12th Podolski Lancers Regiment, Polish II Corps, entered the ruined Abbey of Monte Cassino and found it abandoned.

Few of the Poles now occupying Monte Cassino knew or cared why their opponents had withdrawn so abruptly the night before. In truth, the Nazi Fallschirmjäger (paratroops) dug in there were in grave danger of being surrounded by a phalanx of fast-moving French colonial troops. This column, pushing rapidly through the rugged and mostly undefended Aurunci Mountains south of Cassino, threatened to outflank the Gustav Line—Nazi Germany’s main defensive belt in the region.

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, commanding all Axis forces in Italy, acted decisively to prevent a total catastrophe. First, he personally ordered those paratroopers occupying the high ground at Cassino to retreat before they were cut off and destroyed. Kesselring also began moving reinforcements up to defend a vitally important region known as the Liri Valley.

This wide, flat avenue of advance extended for 90 miles directly toward Rome. Allied mechanized forces traveling along its good roads and mostly dry, level ground could reach Italy’s capital in a few days—that is, unless German defenders managed to establish a fallback line and stop them.

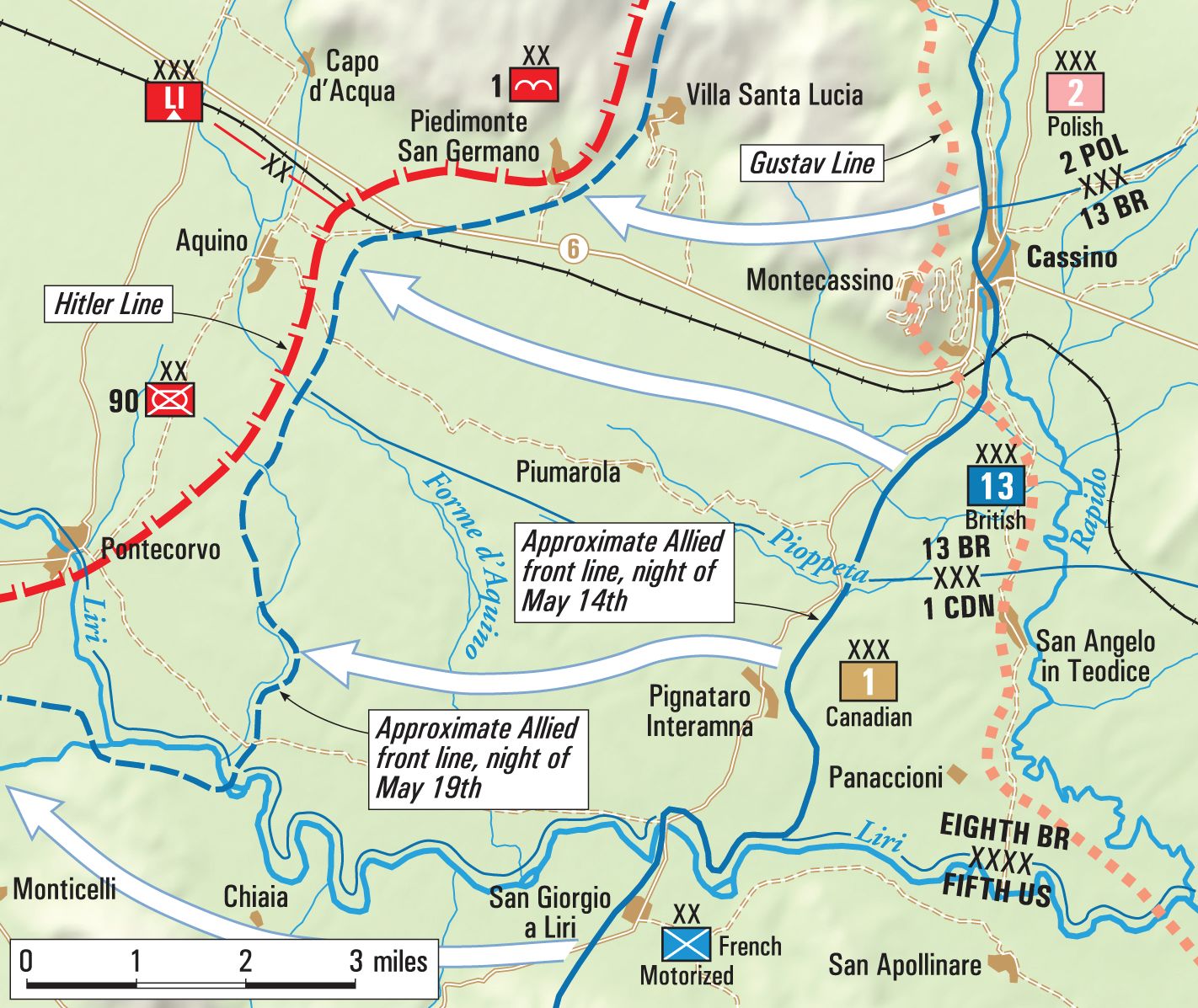

During the third week of May, 1944, the two adversaries began a desperate footrace toward the Liri Valley’s approaches. Could Kesselring’s men reach their contingency positions in time to mount an effective defense, or would fast-moving Commonwealth infantry and armor “bounce” them out before they got into place?

The top Allied officer in Italy, British Army General Harold Alexander, believed his soldiers could rapidly smash their way into the Liri Valley. He had been considering how to do this for some time but needed to build combat power before attempting a major offensive. Finally, after additional troops, tanks, and guns became available, the decisive operation could begin.

On May 11, Alexander launched Operation Diadem using elements of the Fifth and Eighth Armies. His objectives were to crack the Gustav Line, defeat the German Tenth Army, relieve Anzio, and open the Liri Valley to Allied armor. He timed Diadem to coincide roughly with Operation Overlord—by pinning down Wehrmacht forces in Italy, those soldiers could not be redeployed to France.

The opening phases of Diadem went almost exactly to Alexander’s plan. As tough colonial troops from the Corps Expéditionnaire Français advanced across a mountain range to work their way behind the Gustav Line, determined Commonwealth soldiers made a frontal attack on German strongpoints in and around Cassino. Under a massive weight of shellfire provided by 1,600 artillery pieces, these troops charged across the Gari and Rapido Rivers to scale the heights of Monte Cassino against near-fanatical resistance offered by small groups of Fallschirmjäger.

By May 16, Allied efforts were showing signs of success. In a cable to Field Marshal Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, that evening, Alexander boasted: “We can now claim that we have definitely broken the Gustav Line.” Yet he knew the Liri Valley must not be allowed to remain under Axis control. Alexander assigned its capture to the storied Eighth Army—famous for hard-fought victories in North Africa and Sicily.

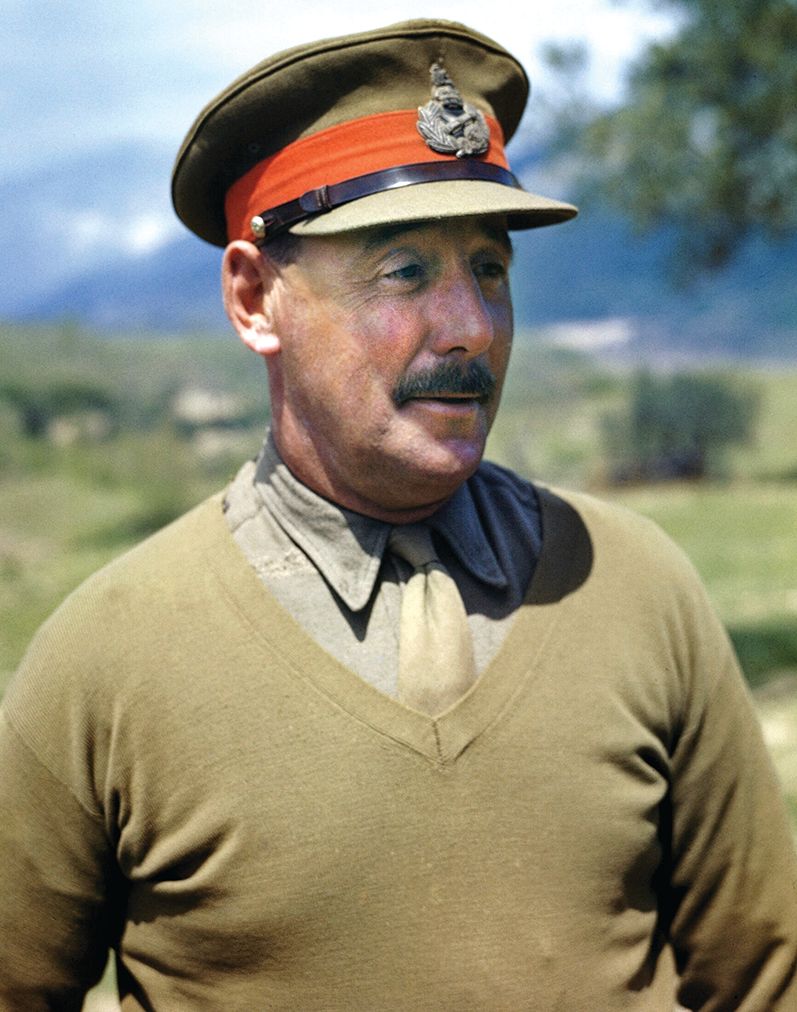

Eighth Army’s General Officer Commanding (GOC) was battle-tested combat leader Lt. Gen. Oliver Leese. As the fight for Cassino reached its bloody crescendo, Leese and his staff began positioning forces for the next phase of Operation Diadem. Orders quickly went out to push west seven miles toward the villages of Pontecorvo and Aquino—gateways to the Liri Valley.

Leese made Pontecorvo the responsibility of the I Canadian Corps, which on May 18 was just moving into its assigned area of operations. He gave the job of seizing Aquino, three miles northward, to British XIII Corps. This formation, commanded by Lt. Gen. Sidney Kirkman, was expected to go on and grab Pontecorvo if its lead elements encountered no opposition at Aquino.

Kirkman’s corps stood in an excellent position to conduct the attack. While two of his divisions (8th Indian and 4th British) had been badly mauled during the fight for Cassino, Maj. Gen. Charles Keightley’s 78th Infantry Division remained relatively fresh after a time spent in reserve. The Battle-Ax Division (a moniker inspired by the shoulder patch its members wore) would be reinforced for this operation by elements of the 6th British Armoured Division and 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade.

The job of taking Aquino fell to Brigadier John J. James’s 36th Infantry Brigade. His command consisted of three rifle battalions: the 5th Battalion, Royal East Kent Regiment (“Buffs”); the 6th Battalion, Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment (“Royal West Kents”); and the 8th Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (“Argylls”).

Providing armored support for 36th Brigade’s attack was a Canadian Active Service Force organization known as the 11th Armoured Regiment (The Ontario Regiment), Canadian Armoured Corps. Commanded by Lt. Col. Robert L. “Bob” Purves, the Ontarios would play an integral role in Eighth Army’s first attempt to bounce its foe from the Liri Valley.

Organized as an active militia battalion in 1866, this unit contributed many volunteers to fight in the Boer War and in World War I with the Canadian Expeditionary Force. In 1936, the outfit converted to armor, as many of its militiamen then worked in the nearby Oshawa car assembly plant and were already familiar with motor vehicles. The Ontario Regiment (the title “regiment” was a traditional cavalry designation—in terms of size and organization, it served as a tank battalion) was activated for World War II on September 1, 1939, arriving in the United Kingdom exactly 22 months later.

First combat for the Ontarios took place during the invasion of Sicily (Operation Husky), in July, 1943. A few months later, the unit joined Eighth Army’s long and costly fight up Italy’s east coast. There the regiment developed a solid reputation for its effective use of armor-protected firepower and shock effect in the infantry support role.

In 1944, the Ontario Regiment’s main weapons system was the M4A4 Sherman V medium tank. Each of its three maneuver squadrons (equivalent to a U.S. Army tank company) was authorized 19 of these vehicles organized into five line troops (platoons in American parlance) of three tanks each, plus a headquarters troop. The squadron commander was typically a major who fought from his own Sherman.

Headquarters Squadron contained the Ontarios’ command group, intercommunication troop, ammunition section, administration troop, and normal service support elements. In April the outfit’s reconnaissance troop received 10 M3A3 Stuart light tanks, each with the turret removed and a .50-caliber machine gun mounted in its place. Troopers named these nimble vehicles “Honeys” and used them for a wide variety of battlefield errands.

While the collapse of the Gustav Line might be viewed as a calamitous defeat for Field Marshal Kesselring, Wehrmacht forces had a superb fallback position that, if properly manned, would block all access to the Liri Valley. It was called the Hitler Line. For the past six months, workers had been turning this so-called “switch” position (as it branched off the Gustav Line) into a most formidable barrier. A New Zealand historian, Robin Kay, described the Hitler Line thusly:

“From the hill town of Piedimonte San Germano the Hitler Line ran southwards across the Liri valley to the vicinity of [Aquino and] Pontecorvo and, after crossing the river, swung south-westwards over the mountains to Terracina on the coast. Although far from complete, its defenses were even more elaborate than those of the Gustav Line; they included armoured pillboxes, reinforced concrete gun emplacements and weapon pits, underground shelters, and minefields and wire to obstruct tanks and infantry.”

The Hitler Line’s man-made strongpoints proved themselves to be both extraordinarily lethal and hard to detect. Machine gunners, one Eighth Army intelligence analyst wrote, occupied “mobile steel cylinders…nicknamed crabs [that] could be inserted in pits above which their steel domes rose to a height of only 30 inches.”

The Eighth Army intelligence officer went on to describe this defensive belt as containing “the turrets of new Panther tanks, eighteen in all, mounting 75mm guns with all-round traverse, which also made barely visible intrusions above their concrete emplacements.” Called Panzerturms, these innovative armored bunkers had never before been encountered on the Italian front.

Behind the Hitler Line stood 150 pieces of tube artillery, mostly 105mm and 150mm howitzers. Several batteries of 150mm and 210mm Nebelwerfer rocket launchers augmented these field guns. For short-range indirect fire missions, the Germans employed large quantities of 80mm and 100mm mortars.

While the Hitler Line appeared truly impregnable, the Führer felt his name could not be associated with a system of fortifications that might in fact be defeated. In May 1944, he directed Kesselring to rename it; accordingly, this defensive network became known as the Senger Line after Fourteenth Army commander General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin. Allied officers, however, continued to call it the Hitler Line.

The deteriorating situation in Italy required Kesselring’s direct involvement. On May 15, recognizing the Gustav Line was about to fall, he issued orders to his principal subordinate commander in the region, Tenth Army’s Colonel General Heinrich von Vietinghoff. “I consider withdrawal to the Senger position as necessary,” Kesselring ordered as he put into motion a fighting retreat by thousands of hard-pressed German soldiers that took place over three days and nights in mid-May 1944.

Some of these troops were ordered to hold the Liri Valley as part of Gen. Valentin Feuerstein’s LI Mountain Corps. Feuerstein had many tasks to accomplish and few soldiers with which to do so. His primary mission required LI Corps to defeat an expected Allied attack against the gateway towns of Pontecorvo and Aquino, but Feuerstein could neither ignore the Poles to his north nor the French mountaineers threatening his southern flank. He also needed to keep Route 6, the chief supply artery leading to Rome, open for Wehrmacht traffic at all costs.

During the German retreat, quite a few fighting men became separated from their commands; upon arrival at the Senger fortifications, they were formed into provisional battle groups (Kampfgruppe) and placed wherever needed. Other reinforcements, such as those belonging to the 90th Panzergrenadier Division, entered the Liri Valley one unit at a time.

Since February, General Richard Heidrich’s 1st Fallschirmjäger Division had stubbornly defended Monastery Hill while inflicting heavy losses on Allied attackers. Those “Green Devils” who fell back to Aquino joined an ad hoc task force under Col. Ludwig Heilmann, commanding officer of the 3rd Fallschirmjäger Regiment. Kampfgruppe Heilmann primarily consisted of paratroopers from that regiment’s 1st and 2nd Battalions, while gunners belonging to the 1st Fallschirmjäger Division’s anti-tank company crewed as many as 10 Panzerturms placed along this section of the line.

It is impossible to estimate the number of German soldiers holding Aquino—indeed, even their commanders did not know how many men were on hand. An Eighth Army intelligence summary suggested as many as 3,500 Wehrmacht troops stood on the Hitler Line between Aquino and Pontecorvo. Alternatively, Canadian post-battle evaluations stated that only 775 Fallschirmjäger were present for duty on May 19, 1944, although more may have filtered in over the next few days.

The ancient town of Aquino, founded in the 4th century B.C., was normally home to a few thousand residents, most of whom had been evacuated by mid-May. While the village itself held no tactical value, it did serve to help anchor the Hitler Line’s flank. Allied mechanized units could not advance into the Liri Valley without first taking Aquino.

The hard-surfaced Route 6 and a parallel railway bed led west from Cassino past an abandoned airstrip to brush the village’s northern edge. Orchards and olive groves concentrated on the north and south sides of town provided some measure of cover and concealment for attacking forces. The center, however, was more open. A large cemetery, sitting about halfway between the airfield and Aquino, dominated all approaches from the east.

Adding to the challenges of terrain was a steep ravine cutting through the village and past Pontecorvo to the south. This gully, the Forme d’Aquino, served as a natural anti-tank ditch that channeled armored vehicles into kill zones where Green Devils and Panzerturms lay in wait. Tanks could only cross the Forme d’Aquino on heavy duty bridges such as the one spanning Route 6 north of town.

Throughout the day on May 18, weary Fallschirmjäger moved into position and readied themselves for battle. Meanwhile, several miles to the east, a number of British scout teams began probing the Hitler Line. In late afternoon, three light tanks from the 6th Armoured Division’s reconnaissance regiment (temporarily attached to the 78th Infantry Division) entered Aquino for a brief period. Their accompanying infantry was held up, though, and the tanks had to withdraw after sunset.

When news of this action reached 78th Division’s General Keightley, it convinced him that a hastily organized attack might succeed in pushing its way through the foe’s defenses. Accordingly, Keightley’s staff issued a series of oral orders designed to mass overwhelming combat power against what were believed to be small, disorganized pockets of resistance occupying this section of the Hitler Line.

The Battle-Ax Division’s main effort would be made by motorized infantry and armor belonging to the attached 6th Armoured Division. A supporting effort conducted by 36th Brigade was to go in on their right at Aquino, while riflemen from I Canadian Corps’ Royal 22e Régiment would seize Pontecorvo to the left. Allied artillery and mortars stood by to fire a preparatory “stonk” (bombardment) and provide chemical smoke to conceal the assault forces. The attack was set to commence at 0515 hours on May 19.

Purves, the Ontario Regiment’s Officer Commanding (OC), first heard of this plan at 2130 hours on May 18 when Brigadier James directed him to move his unit to a lying-up point south of the Aquino airport. They arrived there by 0200 hours on the 19th. In the meantime, Purves joined an orders group in progress at the 5th Royal East Kent Regiment (5th Buffs) headquarters.

There the 5th Buffs’ OC, Lieutenant Cololonel Geoffrey Monk, outlined his scheme of maneuver. From their positions south of Aquino’s airport, Monk’s riflemen would attack northwest to seize a bridge crossing over the Forme D’Aquino just beyond the village. A secondary road leading into town acted as the axis of advance; one company of infantry was to stay south of this byway while another kept to its north.

As soon as Monk’s orders group broke up, Purves briefed his squadron commanders by candlelight in the back room of an abandoned farmhouse. He directed B Squadron (Major Douglas H. McIndoe, commanding) to accompany the Buffs’ attack into Aquino. Maj. Harry Millen’s A Squadron was to guard their right flank while providing covering fire from positions north of the airport. C Squadron (led by Maj. Lyle A. Gerry) would remain in reserve.

The Ontarios’ orders group concluded just before 0500 hours, leaving Purves’ squadron commanders with little time to orient their men on the plan and move to a forming-up place where the 5th Buffs’ infantrymen waited. At 0515 hours the attack began.

Early morning mists both protected the Allied assault force from observation and slowed its advance due to poor visibility. Lt. John Richardson, a troop commander in A Squadron, said the fog was so thick that he “couldn’t see the tank ahead of me and I was practically touching it.”

At 0700 hours, heavy automatic weapons fire pouring out of Aquino’s cemetery brought the Allied advance to a halt. Shermans from B Squadron then deployed in an attempt to locate and silence these guns. This maneuver attracted some unwanted attention; at 0745 hours, McIndoe reported that one of his tanks had been destroyed by an unseen anti-tank (AT) cannon.

On the left side of the road, Lieutenant Keith D. McCord’s troop advanced under cover of a vineyard until it emerged out into the open just 300 yards from Aquino. An enemy AT gun to the south opened up on the Canadian tanks; reacting quickly, they destroyed it with a volley of 75mm rounds. Then a Panzerturm on their right brought the Ontarios under point-blank fire. All three of McCord’s Shermans were hit at least twice, but his crewmen kept trading shells with the foe until it got too hot to remain inside. One man, Trooper John T. “Jack” Phillips, failed to escape from his burning vehicle; his body was never recovered.

In the meantime, A Squadron had reached the railroad line that marked its northern limit of advance. Millen sent a troop of Shermans along Route 6 toward Aquino with orders to loop around and cut off the foe. This effort was stymied by the lifting fog, which exposed Millen’s tanks to Panzertrums emplaced on high ground north of town. Worse still, Allied artillerymen started running out of smoke shells that had been screening the Ontarios’ right flank from observation. Cargo trucks were dispatched to get more from nearby ammunition dumps, but the task of resupplying friendly howitzers with additional smoke rounds would take hours.

As the morning wore on, Purves released his reserve, Gerry’s “C” Squadron, to help secure the battlefield’s northern edge. Already, though, the 36th Brigade’s attack was bogging down. A mortar stonk killed Monk, the 5th Buffs’ OC, and his entire signals section at about 0930 hours. After that it was no longer possible to communicate effectively with the infantry, which greatly increased the danger of a friendly fire incident.

Also at 0930 hours, B Squadron’s McIndoe reported the loss of two more Shermans. His second-in-command (2IC), Capt. John I. Nicol, was wounded around this time as well. Despite the Ontarios’ best efforts, their fight for Aquino’s cemetery seemed to be going nowhere.

Conditions were also deteriorating on the regiment’s right flank. Millen, the A Squadron OC, was knocked unconscious by a sniper’s bullet that ricocheted off his helmet as he stood in the open hatch of his tank. Moments later he was injured again when his tank was hit by a German AT shell. With Millen badly wounded, command passed to his 2IC, Capt. Arthur W. “Bud” Hawkins. That officer’s first act as squadron commander was to ward off a fierce counterattack coming in from the north.

By now, C Squadron had fully entered the fight for Aquino. Although their tanks were picking off numerous pillboxes and towed AT guns, the Canadians were tormented by well-hidden Panzerturms. Lt. James Cameron lost his vehicle to enemy fire as it attempted to cross the rail line, while another C Squadron troop commander—Lt. Albert J. Symons—received severe burns when his Sherman “brewed up” after being hit by a high-velocity projectile.

Corp. Pete Andrew’s tank was also destroyed near the airport. Yelling for the rest of his crew to clear out, Andrew pulled himself free of the burning vehicle only to notice his young co-driver had become frozen with fear inside its crew compartment. Andrew sprinted back to his wrecked Sherman and dragged the trooper out “by main force,” as a unit historian later recorded.

Another crew commander, Corporal Cecil Jones, nearly led his men into German lines that day after they evacuated their smashed tank. Confused by the smoke and dust of battle, Jones crawled for some time in the wrong direction before he realized his mistake and turned around. The tankers made their way back to friendly positions by using a network of drainage ditches surrounding the airport.

Near the railway, A Squadron’s Richardson found a depression in which his troops could hide from one particularly persistent Panzerturm. This gun periodically fired high-velocity 75mm shells that passed inches over the young officer’s Sherman; their concussive effects left him with (as he recounted in 2014) “a bloody headache for three days afterwards.” Only the coming of darkness—and a well-laid smoke screen—enabled Richardson’s tanks to safely withdraw.

As mentioned previously, 36th Brigade’s supply of artillery smoke ran out early in the day. Two Ontario Regiment soldiers, Sergeant Ken Braithwaite and Trooper Kelly Turcott of Headquarters Squadron, took their “Honey” light tank back to a supply depot and loaded it up with smoke canisters before returning to the front line. The regimental history recorded how Braithwaite and Turcott then ran “a wide circle in front of the tanks with their careening machine [while tossing] out the ignited canisters.” It was a foolhardy move, perhaps, but one that likely saved several tanks from the deadly Panzerturms.

The 98th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery, kept busy all day firing chemical smoke and high explosive rounds in support of Allied forces at Aquino. Their “Priest” self-propelled howitzers harassed troop concentrations and suppressed AT guns all along this section of the Hitler Line. A unit historian described how the 98th’s 392nd Battery, long associated with the Ontario Regiment, “toiled from dawn till dark to smoke that right flank or, when the smoke ran thin, shelled and shelled to keep the enemy from loosing a slaughter on our lads.”

Later in the day, word came down that 78th Division’s main attack on the Ontarios’ left never materialized. This meant the 36th Brigade was stuck holding an exposed salient in the lines into which German paratroopers were pouring fire from three sides. Purves received orders to hang onto what ground had been gained until nightfall then move all operable tanks to a “harbour area” south of the Forme D’Aquino for refitting.

The Ontario Regiment disengaged at dusk then moved back to take stock of its losses. A total of 13 Shermans were completely destroyed: 12 by AT fire and one blown up by a mine. Every single tank in A and B Squadrons suffered damage from mortar or artillery fragments. Personnel losses, however, numbered just one man (Trooper Phillips) missing in action and five soldiers wounded.

Balanced against this toll were the Wehrmacht outposts eliminated, AT guns silenced, and Panzerturms neutralized by Canadian crewmen. The Ontarios further claimed to have killed a German tank and one self-propelled gun during their attack on May 19. No record of casualties suffered by Kampfgruppe Heilmann at Aquino has survived.

While most of the regiment’s troopers tended to their Shermans or grabbed some sleep, one soldier worked tirelessly to care for his comrades. A 17-year-old jeep driver named Cecil “Westy” Westover spent three days and nights evacuating casualties back to the regimental aid station with nothing more than a single cup of tea taken to sustain himself. During this time, it was estimated that Westover brought nearly 180 wounded tankers and infantrymen off the battlefield.

Eighth Army’s hastily organized attempt to bounce the Hitler Line had ended in failure. To the south, I Canadian Corps’ assault on Pontecorvo bogged down quickly as the “Van Doos” of Royal 22e Régiment came under heavy fire from German panzergrenadiers. No one knows why the 78th Infantry Division’s armored thrust in the center never came off. A lack of bridging assets needed to cross the Forme D’Aquino may have contributed to this abortive attack.

Writing to his wife, Eighth Army GOC Leese admitted that he underestimated the will of those Germans holding the Hitler Line, as well as the strength of its fortifications. “We came up against strong defences with barbed wire, ditches, and with boxes and anti-tank guns,” Leese reported. “It will be a tough nut to break.”

Captain Ion Calvocoressi, Leese’s senior aide-de-camp, agreed. “A disappointing day,” he noted in his journal. “In the early morning we had hopes of breaking through the Hitler Line without a battle, but now it is evident that we shall have to fight for it.”

Over the next few days, Eighth Army made preparations for a more deliberate assault on those enemy strongpoints blocking access to the Liri Valley. While the Ontario Regiment’s troopers would not participate directly in it, their countrymen serving with I Canadian Corps unleashed a ferocious attack against Pontecorvo beginning at 0600 hours on May 23. Two full brigades of infantry, each supported by a regiment of British tanks, went forward under foggy conditions that morning.

When the Fallschirmjäger who were dug in at Aquino fired on this assault force, Allied artillery responded with a 668-gun barrage. “In a couple of minutes,” recalled Sergeant Victor J. Bulger of the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery, “some 74 tons of high explosive crashed down on the town and completely demolished it.” Two days later, a patrol from 78th Division entered the ruins of Aquino and found it entirely abandoned.

The Hitler Line had finally been smashed. Eighth Army’s tanks, self-propelled howitzers, and infantry carriers began pouring into the Liri Valley on their way to a rendezvous with Fifth Army forces then breaking out of the Anzio beachhead. But now a question arose: once the Allied armies in Italy reunited, would they continue their pursuit of Kesselring’s fleeing troops or allow themselves to be distracted by a politically desirable but militarily insignificant objective?

Thirty miles to the north, Rome—the glittering Eternal City—beckoned.

Patrick J. Chaisson is a historian/writer based in Scotia, New York. The author wishes to thank Jeremy Blowers and Sam Richardson of the Ontario Regiment Museum, as well as Ontario Regiment Historian Rod Henderson, for their assistance with this article.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments