By Flint Whitlock

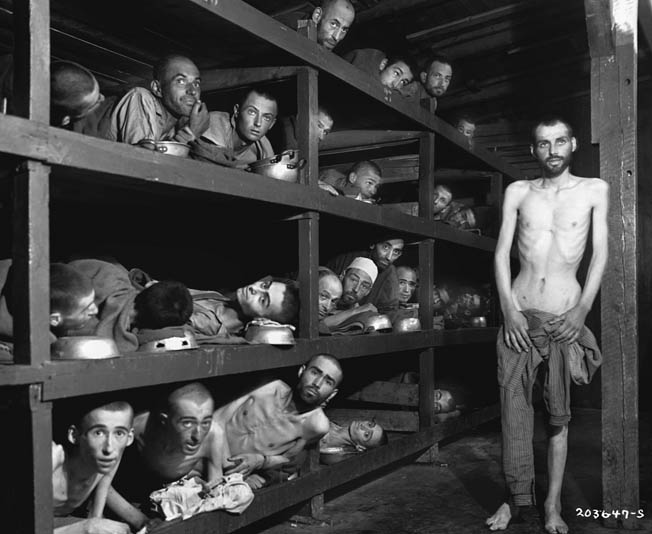

In early 1945, the 50,000 starved and brutalized prisoners incarcerated at KL Buchenwald—the infamous concentration camp located atop a hill known as the Ettersberg, just to the northwest of Germany’s cultural capital of Weimar—were growing desperate.

Ever since the camp opened in the summer of 1937, it had been a place of unremitting horror. Crowded together in filthy, lice-ridden barracks, forced to work in inhuman conditions in the camp’s limestone quarry, used as human guinea pigs in macabre, pseudo-scientific experiments, starved and beaten by sadistic guards, and compelled to perform nightmarish jobs in the camp’s six-oven crematorium that barely kept up with the ever-increasing number of corpses, the inmates were at the end of their tether.

Other inmates, decorated with particularly interesting or colorful tattoos, were selectively killed and their skin made into lampshades and other household objects ordered to adorn SS homes and offices.

Escape was virtually impossible, and revolt was even less likely. The SS guards with their machine guns in their tall watchtowers kept a close eye on the inmates, and the high-voltage barbed wire that ringed the prisoner enclosure invited a swift and painful death to anyone who tried to squirm through it.

Of the more than 40,000 camps of all sizes and purposes within the Third Reich’s sphere of influence, KL (for Konzentrationslager) Buchenwald was one of the largest and most important. It had been built primarily to hold political prisoners.

Jailed here during the camp’s eight years of existence were some of the most prominent anti-Nazi politicians in Germany and elsewhere in occupied Europe. French politicians, especially, were “guests” of the Nazi regime at Buchenwald. Léon Blum, a Jew and the former premier of the French Popular Front government from 1936 to 1938, was imprisoned here after the French Free Zone was occupied by the Germans in November 1942, following the Allied invasion of North Africa.

Other members of the French government incarcerated at Buchenwald included Édouard Daladier (prime minister in 1940); Georges Mandel (the last minister of the Interior before the fall of France in 1940); General Maurice Gamelin (commander-in-chief of French and British forces in 1940); and General André Challe (a prominent leader in the Resistance). Paul Reynaud, the last prime minister before France fell, spent one day at Buchenwald before being jailed at Itter Castle in the Tyrol.

Also locked up atop the Ettersberg were Professor Alfred Balachowsky, director of the Pasteur Institute, and the wealthy, aristocratic Robert-Jean de Voguë, head of Moët-et-Chandon (vintners of Dom Pérignon, the world’s most prestigious and expensive champagne).

At Buchenwald also were kept prominent Germans who had run afoul of the Hitler regime: Dr. Rudolph Breitscheid, former chairman of the German Social Democrat Party, and his wife; and Ernst Thälmann, the leader of the KPD (German Communist Party).

In the cellar of one of the SS troop barracks was a special row of cells known as the SS Detention area, where the Protestant theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer was jailed. (Later evacuated to Flossenbürg, Bonhoeffer was hanged on April 9, 1945, just days before the camp was liberated.)

KL Buchenwald did not discriminate when it came to the nationalities of its prisoners. In addition to Dr. Petr Zenkl, the former mayor of Prague, Buchenwald also held Anton Falkenberg, head of the Copenhagen police, and British Wing Commander Forest Yeo-Thomas. Here, too, was Austrian-born psychologist Bruno Bettelheim. A former prime minister of Belgium, Paul-Emile Janson, died at Buchenwald in 1944.

The Nazis were particularly hostile toward writers and intellectuals who didn’t toe the Nazi Party line—even if they were foreigners. Leon Jouhaux, a French trade unionist and recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature, was imprisoned at Buchenwald, as were French writers Jean Améry and Robert Antelme; the German author Ernst Wiechert; the Austrian poet and dramatist Jura Soyfer; and Curt Herzstark, an Austrian and the father of the pocket calculator. Konrad Adenauer, the former mayor of Cologne, was also jailed at Buchenwald (he would be the first postwar chancellor of West Germany).

Two children who would grow up to be famous authors survived KLB: Elie Wiesel and Imre Kertész. Wiesel’s chilling 1956 autobiographical novel, Night, was based on his experiences at Auschwitz and Buchenwald; in 1986 he would win the Nobel Peace Prize. Kertész would win the 2002 Nobel Prize in Literature for a body of work centered on the Holocaust.

High-ranking German officers who spent time at Buchenwald included General Friedrich von Rabenau, implicated in the July 20, 1944, plot to kill Hitler (Rabenau was executed April 15, 1945, at Flossenbürg).

When the Nazis couldn’t arrest their enemies, they often arrested the family members of their enemies. Ten members of the Stauffenberg family were held in the isolation barrack after the July 20, 1944, attempt on Hitler’s life. Also in custody was the wife of Generaloberst Franz Halder, Hitler’s former chief of the General Staff, suspected of being involved in the plot. (Halder himself was arrested and later held at Flossenbürg and Dachau.)

Industrialist-turned-Hitler-opponent Fritz Thyssen and his wife were jailed at Buchenwald along with the sister of anti-Hitler German diplomat Hans Bernd Gisevius, involved in the July 20 plot, and who had fled Germany for Switzerland.

Few woman were held at Buchenwald, but perhaps the most prominent was Princess Mafalda of Savoy—one of the daughters of Italian King Victor Emmanuel III. Although married to a German official, she hated Hitler and was imprisoned for her outspoken beliefs.

There was an annex at Buchenwald, called the “Little Camp,” built to supplement the overcrowded inmate barracks. Consisting of a couple dozen prefabricated horse stables, newly arrived prisoners spent their first few weeks there in a kind of quarantine. Once it was determined that they were safe to be mixed in with the general prisoner population, they were “promoted” from the Little Camp to the Main Camp.

One of the prisoners said, “Life in the Little Camp was as demeaning as it could be. The Jews in the neighboring stable, all originally from Central Europe, were extremely thin and dying like flies. The sleeping arrangements were hard to believe; in each of the buildings, which were 40 meters long and 10 meters wide, as many as 2,000 human beings were crammed.

“Wooden shelves, each holding four or five or six men, formed bunks four tiers high. The weakest soon found themselves at the edge of the span where, if they died, they were more easily ejected into the corridor and, in the morning, more quickly removed to the crematorium.”

ALLIED AIRMEN AT BUCHENWALD

Buchenwald was not a POW camp, but 168 American, British, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand airmen were held there temporarily. Canadian airman Arthur Kinnis, a bombardier shot down in an Avro Lancaster over France, remembered their journey from Paris to Weimar. In August 1944, they were crammed onto trucks and taken to one of Paris’ railroad stations, where they were shoved into filthy cattle cars. Eighty to 95 men were forced into each car, the dimensions of which Kinnis estimated at 10 by 25 feet.

“There was barely room to sit,” Kinnis said, “providing all against the walls kept their knees up to allow those in the middle leg room. The doors were wired shut. We had no baggage, otherwise it would have been impossible.” Kinnis learned later that this train was the last transport to leave Paris before the liberation and contained 1,650 men and 803 women.

Kinnis recalled, “There is no need for me to mention how limb-weary from lack of proper space we all were. The dirty and filthy conditions under which we found ourselves were so beyond our imaginations that we found it difficult to believe that this was happening to us. What lay ahead of us we dared not think for, if this was a sample of the new German culture, we wondered just what we would see and go through before our eventual release.”

The captives all assumed they were headed to a prisoner-of-war encampment, where they would sit out the rest of the war in diminished, but not life-threatening, circumstances.

A week after departing Paris on a harrowing journey full of threats of death, however, the grimy, thirsty, famished POWs reached Buchenwald—on August 21, 1944. Climbing the Ettersberg in reverse, the train backed into the railyard adjacent to the Gustloff-Werk II, and the prisoners were ordered out, accompanied by shouts and the barking of angry Alsatian guard dogs.

As Kinnis and his sweating companions glanced at the nearby factory and wondered what sort of POW camp they had come to, “one American was hit for no apparent reason by a swaggering German officer. Our spirits were on the ebb.”

Under armed guard, the group was marched inside the electrified enclosure. Kinnis took stock of his surroundings—rows of barracks as far as the eye could see, watchtowers bristling with machine guns and manned by SS guards, and a building—the crematorium—from whose tall, square chimney streamed a constant plume of foul-smelling, dirty-gray smoke.

The sightseeing quickly ended as the group of Allied airmen were hustled down to the delousing station and had all their body hair shorn by a group of Polish “barbers.” “It was done so fast that one didn’t have time to question where those clippers had been before they were being used on you,” Kinnis said.

Just as quickly the POWs, more hairless than newborn babes, were issued a striped shirt, pants, a brimless cap, but no shoes, and marched a few hundred yards across the rocky, uneven ground to Buchenwald’s quarantine section—the dreaded Little Camp.

There Kinnis and his fellow POWs were aghast at the conditions they found: five big tents all crowded to capacity, 14 permanent barracks (some of which were former horse stables), one small stone building used by the Lagerältester (a camp elder or barracks chief) and his assistants, plus two foul-smelling latrine buildings. Scattered here and there around the Little Camp were stacks of corpses waiting to be hauled to the crematorium.

Kinnis estimated the number of prisoners in the Little Camp alone to be about 10,000. Everyone received a prison number; Kinnis was assigned number 78391. A watery, lukewarm “soup” was ladled out to the new arrivals that night.

The arrival of the airmen created quite a stir within the Little Camp, with everyone seemingly amazed that a group of Allied fighters had been suddenly thrust into their midst. Everyone wanted news of what was happening in the war and in the outside world; the Allied airmen gave their rapt audience as much information as they could about the D-Day invasion at Normandy, about the Allied push westward, about the battles taking place across France. The confirmation that Paris had been liberated was especially exciting.

When asked in broken English how much longer the Brits, Yanks, and Canucks thought the war might last, the answer, “one month,” caused considerable joy. Smiles began to spread across faces that had long given up hope, that had long forgotten how to smile.

While their presence seemed to bolster the spirits of the other inmates, the fliers’ spirits sank as they contemplated the conditions of their imprisonment. There were not enough tents to accommodate the new arrivals, so the Allied airmen were forced to sleep in the open without so much as a blanket. In spite of this, the exhausted POWs fell into a quick, deep sleep on the hard ground.

Before sunrise the next morning, the inmates of the Little Camp were all ordered to report for roll call. The roll calls were twice-daily exercises in sadism and cruelty, like a college fraternity Hell Week run amok. Kinnis recalled seeing men beaten—not only by the SS but also by the Kapos (usually brutal prisoners designated to maintain order) and Blockälteste and their assistants—for the slightest infringement of the rules.

It now sank in to Kinnis and the other Allied airmen that instead of being in a relatively safe POW camp, as required by the laws of warfare, and guarded by Luftwaffe personnel, they were in the terrifying jaws of the Third Reich—their life or death at the whim of the SS.

Designated Terrorflieger (terror-fliers), the airmen were denied access to the International Red Cross or recognition as official prisoners of war. Kinnis said, “We knew that our group must become very united and that we must make sure that the powers that be realize that we are all aircrew of the Allies, and that what is now happening to us is against the Geneva Convention.” But how to accomplish that?

The airmen tried adjusting to their horrid living conditions as well as they could. Luckily, the Ältester in their section of the Little Camp, a man with a wooden leg and a sense of humor, was decent to the airmen and tried to make their existence as bearable as possible. Because the Little Camp was already beyond overcrowded, nothing could be done immediately to get the airmen out of the elements at night, and so they continued to sleep on what they called “the rockpile.”

V2 ROCKET COMPONENT PLANT

Given the exigencies of the war, a change had taken place within the world of concentration camps. No longer were the camps merely places where sadists could practice their trade with mindless cruelty. With Germany’s industrial manpower needs increasing to keep pace with the ever-widening war, a new emphasis was placed on turning the hundreds of thousands of inmates into slave laborers for German industry and extracting the maximum amount of productive work from each one.

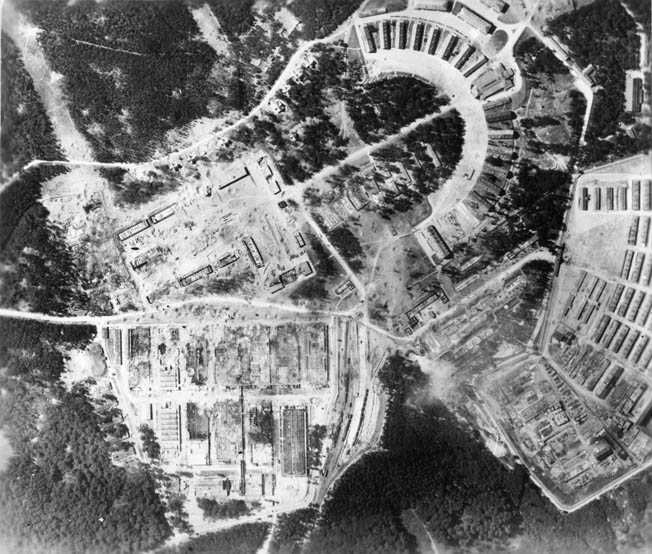

As a result, in 1943 Buchenwald became home to an immense factory—known as Gustloff-Werke II—where inmates made component parts for the mighty V2 rockets. The sprawling plant was staffed by German technicians and several hundred inmates whom the Germans thought were sufficiently skilled to work on the component-assembly line. When finished, the components were crated and shipped to the Mittelbau-Dora underground V2 factory, 35 miles northwest of Weimar, for final assembly.

Inmate Louis Gros, a teenager from France, said that working in the factory was a godsend to many of the men who were on their last legs. There were flushing toilets, a washroom, decent food, and supervisors who rarely screamed at them or beat them with rubber truncheons. It was as close to a normal existence as could be found at Buchenwald.

While some inmates were content to try to survive the war by making as few waves as possible, others were intent on either escaping or doing whatever they could to punish their antagonizers. An underground camp committee was formed that was dedicated to escape and revolt, but they knew that, being hundreds of miles behind the front lines, their rescue would not come soon.

What if, one of them hypothesized, we could tell the Allies about the V2 components being manufactured at Buchenwald? Wouldn’t the Allies place a priority on destroying that factory? And if the factory were destroyed, wouldn’t it also mean that some or all of the inmates would be able to escape. Of course, realistic voices noted, the Germans would hunt down the escapees and either kill or reincarcerate them, but perhaps enough would get through to the Allies to tell them what had been going on in the camp.

A few of the inmates had either constructed or smuggled in radio receivers, so they had a good idea about what was taking place in the outside world. And as many as seven clandestine radio transmitters existed in the camp. Inmates, at the risk of their lives, began secretly transmitting details about their precarious situation.

There were also messages that contained information that the components for the guidance system of the V2 rockets were being manufactured by slave labor at the Gustloff-Werk II, along with a request for the Allies to bomb the factory.

None of the inmates knew if anyone outside had received their messages, or if they would act on them if they had. But one clear morning in the summer of 1944, before reporting for work at Gustloff-Werk II, inmate Louis Gros looked up and saw a lone airplane streaking a white contrail across the sky above KL Buchenwald, meaning the air was dry—a good day for a photographic mission.

One of Gros’s comrades, a man named Jean Taillez, asked him, “That one––do you think he’s a tourist?”

The two men noted that the plane made several passes over the camp and the factory before disappearing. They wondered if it presaged something less than benign. Was the Gustloff-Werk II being singled out as a target?

“Yeah, reconnaissance at high altitude. That kind of tourist travels much and apparently finds pleasure in it.”

It was not until August 24, 1944, that the inmates at KL Buchenwald realized that their many secret messages to the Allies had been received—and were about to be acted upon.

MISSION 132

On that day, 129 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers of the 613th Bomb Squadron, 401st Bombardment Group lifted from their base at RAF Deenethorpe, 100 miles north of London, and headed toward Weimar and their target, Gustloff-Werk II, 500 miles to the east. It was an operation known as Mission 132. The aviators were given the task of destroying the factory.

Lieutenant Colonel Allison C. Brooks, the group’s operations officer, later told an interviewer, “In the briefing on the Weimar mission, the intelligence officer stressed that there was presumed to be a concentration camp next to the factory and that we were to make every effort for precision bombing, right on the target and the confines of the target only.”

Joseph J. Geraldi, a crewman on one of the B-17s assigned to hit the target, said that he recalled no mention of a concentration camp during the briefing. “We were never told a concentration camp was there. Hitler was sending V1 and V2 rockets to England, so we were well aware of the rockets, and that was our target for the day. What we were told at briefing was, ‘Today we are going to hit a V2 factory at Weimar.’”

Indeed, in none of the 613th’s official reports is there any mention of Buchenwald or a concentration camp; the target is simply designated as “a factory.” Only in one document in the report file—a handwritten scrap of paper without the identity of the person who wrote it—are the words “concentration camp” even mentioned.

Geraldi was not looking forward to the mission to Weimar. He said that the group had attacked nearby Leipzig four days earlier: “It was terrible—we got shot up pretty bad.” And he feared that Mission 132 to Weimar/Buchenwald was going to be just as bad.

With his aircraft (No. 42-31591), piloted by 2nd Lt. Frank Carson, Jr., flying the “low box,” they did not make it to Weimar. “One hundred fifty miles south of Berlin, we got hit by fighters,” said Geraldi, who was serving as the plane’s belly-turret gunner that day. “We had to jettison our bombs and return to Deenethorpe after receiving pretty severe damage. Three other planes were shot down on that mission.”

Air raid warnings were a common occurrence at Buchenwald, but all had been false alarms until that August 24; no bombs had, as yet, fallen on or near the camp. Like children at a school fire drill, the prisoners at Buchenwald looked forward to the wailing of the air raid sirens, for it meant, for a short time at least, that they were granted a reprieve from beatings and their onerous chores.

Shortly after noon on August 24, the sirens wailed and camp personnel scrambled for the air raid shelters, half expecting that it was yet another false alarm. Many of the workers inside the factory, along

with their German supervisors, began heading for the exits. The prisoners had no shelters; all they could do was take cover on the bare ground.

Within minutes, the deep-throated growl of hundreds of Pratt and Whitney engines pulsated the air molecules and assaulted the eardrums. The guards and the inmates could see, off to the north, a dark cloud looming ever larger. No one could be sure if the air armada was headed for Buchenwald or for Weimar, just beyond, or for some other target.

Canadian airman Art Kinnis had been enjoying an idle, sunny day in the Little Camp when he also spotted the formation of B-17s heading his way. “Being at 22,000-25,000 feet,” he said, “their appearance in perfect formation was a lovely sight, a remark that was passed by many of us.

“Just as the leading ship was directly over us, we saw a white smoke puff go down. The Americans and bomb aimers among us recognized this for was it was: the signal to drop their load.”

Louis Gros, one of the inmates working in the factory, recalled that, while the air raid sirens were blaring and the complex was being evacuated, “We raised our heads and saw a quite extraordinary sight. The scene was terrifying both for its beauty and its extravagance. An immense square, straight as a die, had been drawn just overhead, forming a thick white carpet that covered the entire camp.

“The square hid the tracer planes from our view, but beyond it we could see the white lines they had left in the sky. We never saw a single plane! But in the surreal décor we could hear the humming of the aircraft formations. It was clear we were in for an imminent deluge!

“‘Do you think that is for us, all that stuff?’ asked one of the Frenchmen nervously. Some men were more than nervous, not surprisingly. They guessed that this veil that had been drawn over our heads was to facilitate the task of the bombers, but they were not sure whether the purpose was to make a target for the bombs or to drop them around it.

“One of our crowd was more reassuring: ‘No, no. Of course they are going to wipe out everything that is visible outside the square.’ This seemed to make sense. In the same instant the droning noise of a squadron drowned out the hum of the trace planes, which were probably already on the way back to their base.

“In the midst of the droning, which in seconds grew to a roar, the men became confused, each man dreading being caught up in the full tragedy and becoming a forced witness and possibly a victim of the imminent bombardment. No one doubted what was about to happen, but nobody knew, either, what to do. In a few minutes we would probably have to run from the bombs.

“But there was no shelter in the camp, no cellar, not even a hole, with the exception of the ditches filled with corpses in the Little Camp! And we had heard a lot of bad reports about the accuracy of American bombardiers and American bombs. Our camp was a trap, locked in as it was between blocks of factories, the sawmill, the barracks, and all kinds of other buildings….

“In the watchtowers, the SS remained vigilant, imperturbable. They were never going to quit their post, whatever the cataclysm. Their machine guns remained implacably trained on the camp, or to be more precise, on the inmates…. Suddenly, a piercing whistle tore the air and grew louder. It was not the same sound that I heard for the first time above my hometown of Épinal in June 1940.

“Then, there were only a few seconds between the little bombs being released by low-flying Heinkel IIIs and the explosions on the ground: hardly the time to hear a faint squeak or even take flight. And what is more, they missed the target, which was the railway station; they were not even anywhere near!

“But now, in Buchenwald, the whistle we heard was loud, harsh, and upsetting. Not surprising: The aircraft were flying at a few thousand meters altitude, and the bombs they were dropping were high caliber. You could hardly feel indifferent! We were just below the merry-go-round of terror.

“Even though some of us were full of jubilation, recognizing the importance of what was happening (had not our American friends been reducing the major enemy arms centers to dust?), it was fear that was uppermost, grinding our guts and exposing raw nerves. Instinctively, from the opening of the window where I hung, I turned my gaze in the direction of the whistles, now so loud they drowned out the roar of the bombers.

“Thoughts and feelings flooded through me. A great flash of light and, like the knife on a guillotine, then I saw a wall of darkness descend beyond the beech woods that separated the quarry from the camp. The wild, inhuman, and devastating dance had begun. We were about to be liquefied by the conflagration from the bombs, tormented in hell…. The explosions of an unimaginable magnitude had just pulverized their point of impact.

“A second later, enormous columns of smoke and dust rose from behind the forest, taking with them tons of detritus and blending them with the white carpet that still hung above. It was fixed as if on hooks; no wind could blow it away; it seemed indestructible. But now the fragile satin veil was pierced by a hail of debris of all kinds and all sizes, tearing through the roofs, clapping on the ground, sending us flying in search of shelter, some protection, however meager.”

Within minutes the cloud of roaring aluminum was directly over the camp, and the noise of the engines was blotted out by the whistling sounds of incendiary and 500-pound bombs hurtling downward.

Art Kinnis recalled, “It was not over, for we soon spotted the main force, and this time, to our horror, the signal went down before they were directly above. Knowing how a bomb falls, we all knew that these were for us. Each chap endeavored to get lower than his mate and, outside of keeping our heads down, ostrich fashion, no cover was obtainable. I sincerely hope that I never hear the screech, thud, and rumble of dropping bombs again. It was far too close for comfort.”

The scream of falling bombs was replaced almost instantaneously by deafening explosions ripping apart the buildings of Gustloff-Werk II as though they were built of balsa wood. Trees were uprooted by the fiery blasts, and vehicles and railroad cars on the sidings were flipped into the air as if they were toys. From the ruins of the factory, men—upervisors and inmate workers alike—ran in panic, their clothes, hair, and skin on fire. Others were buried by falling debris and airborne mounds of earth and the trunks and branches of shredded trees.

Louis Gros noted, “A second array of bombs, this time out of my view, exploded somewhere to the left of the first. This time they must have hit the SS barracks! Good riddance! But what an infernal noise! A second deluge of stones, bits of wood and metal, etc., descended on our heads. I was astonished to see plates of soup on the refectory table still steaming and covered in plaster, dust, and bits of debris of all kinds. Some prisoners were still trying to eat this rather special brew, apparently unconcerned by the din outside….

“And it was not yet over! Panic set in everywhere. Normally there was hardly any movement in the camp during the day, save for the work parties, but now it emptied of prisoners in a wild rush, the mad stampede of a herd of animals in flight towards the lower end of the camp and the purely theoretical protection of the forest, the point farthest away from the target zones.

“Further waves of bombers flew over, further explosions followed, now farther away from us, over by the factories. If you listened carefully, you could hear the squadrons of aircraft coming and going in the midst of the diabolical noise. The explosions were close and fast, immediately followed by enormous bursts of flames and smoke, creating a fantastic cloud that twisted painfully into the sky. This was the big fireworks show we had all been waiting for, and it was for free! But not, alas, in terms of human lives.”

One of the factory workers, Willi Gugig, who had been in Buchenwald since 1939, was hit by flying debris while taking cover in the woods and knocked unconscious. When he came to, he saw smoke and flames all around and some of his workmates dead, covered with roots and branches and upturned earth. He got up and began running to get away from the hellish scene and noticed a panic-stricken SS guard sprinting alongside him.

Then Gugig expanded his vision and saw scores of inmates and guards all running for their lives in the direction of Weimar. (The prisoners’ freedom did not last long; later that day, those who had escaped the bombing were rounded up and brought back to camp.)

Sixteen-year-old Salek Orenstein, who worked in the factory but, on that fateful day, had not been at his work station, recalled, “Most of the workers of my shift were destroyed that night; very few came out. There was nowhere to run, nowhere to hide.”

Louis Gros said, “A bomb exploded not far from us, the only one to reach the camp, apparently of low caliber. ‘Did they mean to get the crematorium?’ But no, the Americans, as was well known, dropped their bombs from 4,000 meters altitude. It would be impossible from that height to aim with any precision at a rather small building, standing alone. It was just chance that it nearly hit this target. The crematorium would certainly not have been on their list of objectives to eliminate at any price.

“Now a shower of incendiary bombs came tumbling down. We were getting the whole works! They were invisible. They set fire to the sawmill adjoining the camp on the left, and to the washhouse down below. To the right, in front, and to the left that we could view from the front row.

“At last the white carpet up there was torn apart, as if to say, ‘The show is over!’

“Pamphlets, too, fluttered down and covered the ground. I picked one up, and cautious as ever, hid behind a tree to read part of it. It was a call from one Friedrich von Paulus, a German field marshal of whom we had never heard, mentioning the German defeat at Stalingrad and calling for the end of hostilities. Very interesting. But I dared never be found with this paper on me, so I buried it.”

Benedict D’Agostini, a crewman in B-17 #468 [one of 2nd Lt. M.J. Kochel’s crew), 615th Bomb Squadron, wrote this account of the raid from his perspective: “August 24, 1944––Target was Weimar, Germany, just west of Leipzig. Dropped 10 500# RDX bombs on a factory manufacturing rockets and flying bombs. [RDX is an acronym for Research Department Explosive, and is more powerful than TNT. It is also known as cyclonite, hexogen, and T4].

“Three planes of the low element of the low box of the group lost to Me-109s. Enemy fighters attacked for 30 minutes. Group knocked down one Me-109. Light flak. Flying time 8½ hours. Bombing altitude 23,700 [feet]…. 30-50 enemy fighters attacked in a pack.”

AFTERMATH

The bombs and their fragments did not totally spare the prisoner enclosure. In the Little Camp, Bill Gibson, one of the 26 Canadian airmen, recalled, “The fellow lying next to me said he was hit. I looked, and he had a piece of shrapnel sticking out of his shoulder about an inch and one-half.” Gibson managed to grab the bomb fragment and pull it out, “but I forgot it was red hot, and my fingers got burnt.”

The injured RCAF member was Frank Salt. One of the leaders in the Little Camp helped Salt get to the infirmary, which was overflowing with wounded and dying SS men and inmates. All was chaos. The dead and dying were carted away in horse-drawn wagons while civilian ambulances from Weimar came loaded with bandages and other medical supplies.

In addition to the factory, which was almost completely obliterated and put out of commission for the rest of the war, bombs also fell on the SS garage area and the SS officers’ housing area, smashing villas and killing officers’ wives and children, along with inmates assigned to work in the homes as domestic servants.

Louis Gros recalled, “After the planes had gone and their hum had finally faded following those 15 minutes of diabolical drama, we were back in the strange, almost uncomfortable calm that follows a fearful noise. Looking at all the debris blocking the alleys around the camp, we began to worry about the day-workers in the factory and the other camp Kommandos.

“For us it had taken about 15 minutes when the alarm was sounded to run from the workshops to the woods beyond and below the train station. Had our comrades had the time to get to this summary refuge before the blind and deadly bombs hammered down?

“‘God-almighty bombardment, eh, Jean?’ I said to my friend Taillez, who was anxiously emerging from his bunk.

“‘Yes, I thought we had all had it then,’ he replied uncertainly. He remarked on how accurate the bombs were, hitting their target without touching the camp as such.

“We learned after the liberation of the camp that, for this extremely special and delicate operation that we had just lived through, the U.S. Air Force had used its crack bombardiers and fighter pilots. They had sent us their elite to bomb an elite!”

Gros remarked, “Even if you hate war, even if you think that bombardment cannot be the work of an elite any more than an ordinary killer can belong to an elite, you have to admit that this bombardment was one of the most successful of the entire war, the exceptional means being used here unequalled anywhere else. Contrary to what happened at Buchenwald, the German cities, for example, came out badly, and the French cities, too.

“Everyone around the periphery of the camp survived. It was the beginning of the end. Even the SS were disconcerted. Were they human after all? They appeared to have lost everything, even their arrogance. But still we had to take care. Up above, the sky now held only shreds of the muslin veil that had been so carefully drawn, witness to an event that had been both common and titanic. For a few last moments, we survivors could contemplate this ultimate décor!”

It was a perfect strike, one of the most precise of the entire war. Jim Hastin, an American pilot imprisoned at Buchenwald, remembered that his countrymen “did a beautiful job of bombing. Then the Germans came down and said, ‘All English and Americans out. Leave your stuff; you won’t need it.’ We thought that they were going to take us up and shoot us and then say that we had been killed in the bombing. People shook hands and said goodbye. We felt much better when they said to leave one man to watch our stuff.

Instead of shooting the prisoners, the Germans took them to help put out the fires. Hastin said, “I remember one Polish man that was walking along the road with an armful of incendiary bombs that hadn’t gone off; he thought that he had a supply of wood! Steve Paxton [another POW] told him to gently put them down and get away from them.”

Art Kinnis noted that in order to keep the fires from spreading, the POWs were ordered to tear down with their bare hands all the buildings in the path of the flames. “It is surprising how fast this can be done with many hands working at top speed,” he said.

Those who fought the blaze were not rewarded for their work. Myles A. King, an American fighter pilot, remembered that after the raid, “The SS sought their vengeance on us, the Allied airmen. Their reprisals took the form of brutal kicking, punching, pistol- or rifle-butting at any opportune moment.”

In the chaos and confusion during and after the attack, the secret resistance group within the camp took the opportunity to plunder weapons from the SS armory. The weapons would be needed when it came time to fight back.

When the bombs came crashing down, one of them also blew apart the private home in the “VIP section” of Buchenwald in which Princess Mafalda was jailed. She was buried up to her neck in debris from the collapsed building, and one of her arms was torn and terribly burned.

It was reported that she was carried to the camp brothel, where the women working there cared for her. After being operated on by the camp doctors, her arm became infected and required amputation. She bled profusely during surgery and never regained consciousness; the 41-year-old daughter of the Italian king died during the night of August 26-27. She was buried in a potters’ field in Weimar.

Also dying in the VIP section was Dr. Rudolf Breitscheid, former chairman of the Social Democrats in the German Parliament, and a staunch Hitler foe.

Within the camp itself, the eastern edge—the section nearest the factory—suffered the most bomb damage. The laundry and disinfection buildings were wrecked, as were parts of the crematorium and clothing storage depot. It is estimated that 388 inmates died in the raid, along with more than 100 SS men, their families, and civilian supervisors at the factory.

A huge burial ceremony was held to honor the fallen SS men at Weimar’s Old Cemetery. Hundreds turned out to say their goodbyes to the guards and administrators who had lost their lives during the bombing, but there were no funerals or ceremonies for the 388 inmates who were killed; their bodies were incinerated or dumped into mass graves, their names and final resting places lost to history.

Perhaps the most symbolically important damage was done to the Goethe Oak. An incendiary bomb had set it alight, and it was later cut down; an old German prophecy said that the nation would exist only as long as the Goethe Oak stood.

After the raid, the routine at Buchenwald returned to a semblance of normalcy. The roll call still took place twice a day, the daily beatings and torture sessions resumed, operations in the quarry and pathology lab went on as though nothing had happened, and those who died of disease, malnutrition, or other causes continued to be hauled to the quickly repaired crematorium for disposal.

But, beneath the surface, a profound change had taken place at Buchenwald, a change that had shaken the camp to its core. The knowledge that the Allies could mount such a precise aerial strike on the camp not only kept the guards and staff constantly scanning the sky, but the earlier confidence that Buchenwald was beyond the reach of the Allies and therefore immune to attack was suddenly shattered.

Any day now, worried Commandant Hermann Pister and his SS guards, the advancing Allied armies might appear over the horizon, head for the camp atop the Ettersberg, discover what had taken place there, and exact retribution on the perpetrators; plans were finalized for the liquidation of the camp and its inmates.

Besides the Nazis’ formerly unshakable confidence, the factory was also gone; the destruction of Gustloff-Werk II was a serious blow to Germany’s V2 rocket program, for it drastically curtailed the manufacture of the gyroscopes and other components.

The equipment from the factory that was salvageable was moved to a deserted salt mine at Billroda, about 20 miles north of Weimar. Here, almost 2,000 feet below the surface, the Germans tried to resume production, but the output of V2 components was only a fraction of what it had been.

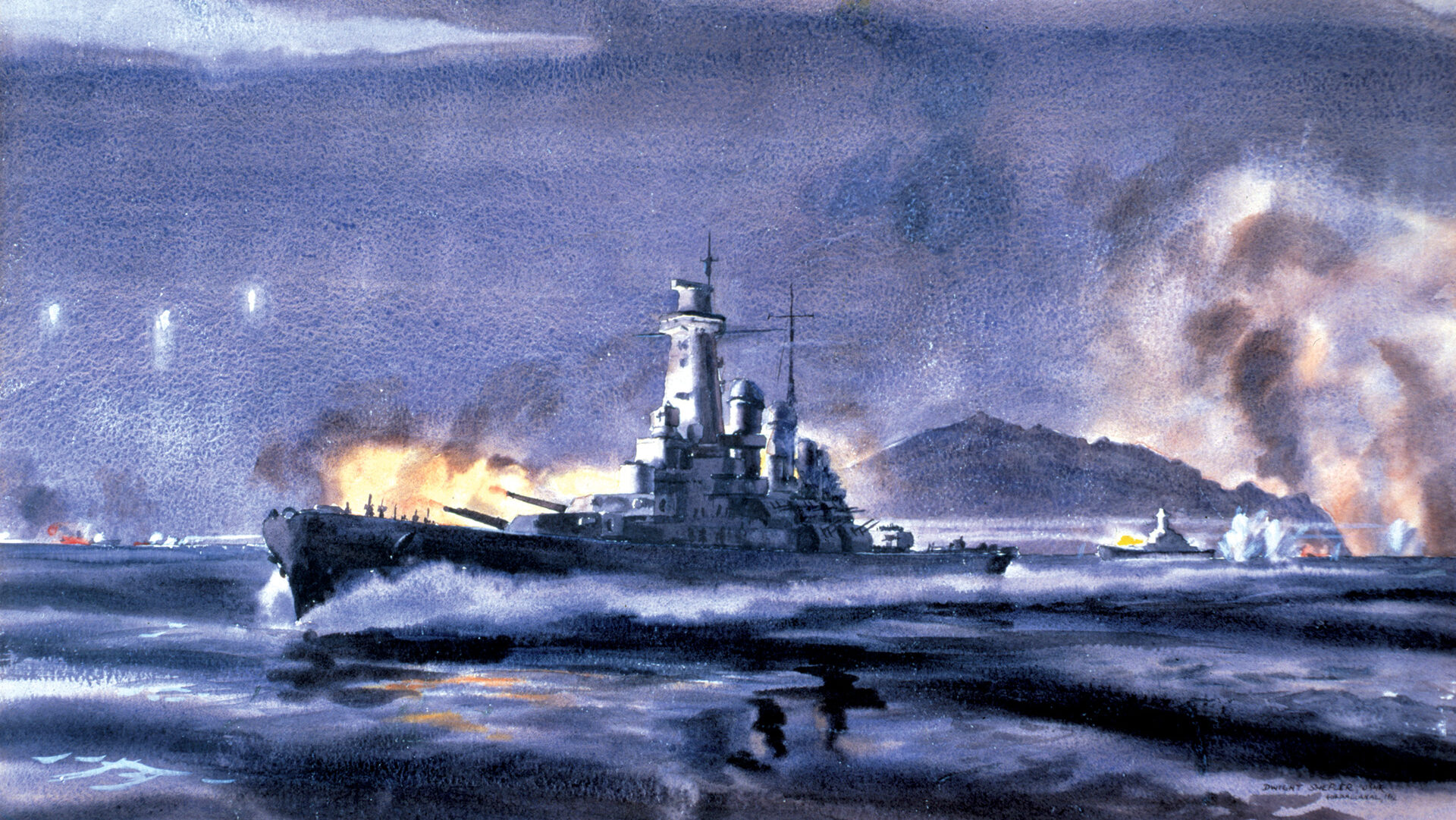

At the beginning of September 1944, the first V2 missiles, assembled by the slave laborers at Mittelbau-Dora, just 66 miles from Buchenwald, were unleashed upon Britain from mobile launching sites 200 miles east of London near The Hague and Walcheren in the Netherlands.

Hitler had once wanted a massed aerial armada of 5,000 V2s to descend on England in a single salvo, but with the launching sites along the Channel coast of France now overrun by the Allies, only 25 of the tall missiles were ready for launch, and then only over a period of 10 days. Sporadic launches, from The Hague and another Dutch site, Hellendoorn, would take place through March 1945.

TO BOMB, OR NOT TO BOMB, THE CAMPS

For several years, pro-Jewish factions in the United States and Britain had been desperately urging the British and American governments to do more to rescue the Jews from destruction in the death camps. Why don’t you bomb Auschwitz? they wondered. Why don’t you at least bomb the rail lines leading to the death camps?

Their pleas were, for the most part, ignored, the excuses for inaction ranging from the death camps being too far from the air bases to the danger of killing and wounding the very people such raids would be designed to save to the difficulty of pinpointing a target as small as a set of railroad tracks.

However, as the pressure mounted, the decision was made that the I.G. Farben synthetic oil and rubber factory at Auschwitz-Birkenau—but not the death camp itself—should be bombed. On September 13, 1944, a fleet of Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers of the U.S. 464th Bombardment Group, flying out of Italy, hit the factory. Some of the bombs missed the Farben works but, by a stroke of luck, destroyed one of the gas chambers at Birkenau. The air strike, however, did not stop the killing operations there.

This pinprick of an air strike prompted more thought and discussion about the possibility of disrupting the deadly work of the camps. On November 8, 1944, John W. Pehle, director of the War Refugee Board, wrote to John J. McCloy, the gnome-like ex-New York banker and now Assistant Secretary of War.

His letter contained two eyewitness reports about the conditions at Auschwitz-Birkenau and made reference to Operation Jericho—the RAF’s precision, low-level bombing attack by 19 DeHavilland Mosquito Mark VI aircraft on the prison in Amiens, France, on February 18, 1944, in which the walls were blown out, enabling hundreds of political prisoners held by the Gestapo to escape. Pehle suggested that a similar raid be made against the death camps. The suggestion was rejected.

In his November 18 reply, McCloy wrote: “The Operation Staff of the War Department has given careful consideration to your suggestion that the bombing of these camps be undertaken. In consideration of this proposal the following points were brought out:

“a. Positive destruction of these camps would necessitate precision bombing, employing heavy or medium bombardment, or attack by low flying or dive bombing aircraft, preferably the latter.

“b. The target is beyond the maximum range of medium bombardment, dive bombers and fighter bombers located in United Kingdom, France or Italy.

“c. Use of heavy bombardment from United Kingdom bases would necessitate a hazardous round trip flight unescorted of approximately 2,000 miles over enemy territory.

“d. At the present critical stage of the war in Europe, our strategic air forces are engaged in the destruction of industrial target systems vital to the dwindling war potential of the enemy, from which they should not be diverted. The positive solution to this problem is the earliest possible victory over Germany, to which end we should exert our entire means.

“e. This case does not at all parallel the Amiens mission because of the location of the concentration and extermination camps and the resulting difficulties encountered in attempting to carry out the proposed bombing.

“Based on the above, as well as the most uncertain, if not dangerous effect such a bombing would have on the object to be attained, the War Department has felt that it should not, at least for the present, undertake these operations.

“I know that you have been reluctant to press this activity on the War Department. We have been pressed strongly from other quarters, however, and have taken the best military opinion on its feasibility, and we believe the above conclusion is a sound one.”

The commonly held picture today of determined Allied armies racing to the rescue of the Jews was a myth, a fiction that goes against the historical record. Today, many—perhaps most—Americans believe that the United States government did everything in its power to rescue the Jews of Europe from annihilation.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. Perhaps this noble mind-set is the result of the postwar prosecution of Nazi officials for war crimes, including most of all what the Nazis had done to the Jews and other oppressed minorities—plus all the books and films and documentaries on the subject of the Holocaust. But that is not the way events unfolded in 1944 and 1945, when the existence of the camps was generally unknown by the average Allied soldier.

Furthermore, would a mass Allied bombing campaign against the Nazis’ concentration and death camps have stopped the slaughter and saved hundreds of thousands of lives? Unfortunately, no one knows.

This article is adapted from the author’s Buchenwald trilogy: The Beasts of Buchenwald, Survivor of Buchenwald, and Buchenwald: Hell on a Hilltop, all published by Cable Publishing of Wisconsin.

Interesting article thank you. My Father Sqn Ldr Stanley Booker RAF was one of the 168 Airmen imprisoned in Buchenwald. He is now 98 years old and I am writing his memoirs

There was never any real interest by either Roosevelt or Churchill for a bombing mission tied to humanitarian reasons. This despite many other missions carried out during the war under much more problematical circumstances. The Doolittle raid, attacks on the Tirpitz submarine attacks in the heavily mined Sea of Japan, and many others. While it is true there there could be no certainty of success had missions been launched against the camps, the fact that no effort was made is one of the disgraces that goes right to the top of command. Rather undercuts the moral slogans of saving the world that were the staple of the allied powers.

Without understanding the priorities in allocating limited resources among competing wartime demands, retrospective opinions, while valid in some context, may not be able to encompass the complexities of that time.