By Amy Wannemacher

The second World War seems like a long time ago for most of the world, with the harsh realities of blitzkrieg warfare and the Holocaust primarily learned through books and films, possibly a museum. Though sadly their number shrinks daily, there remains scattered across the globe many people for whom that era of history is all too real—they lived through those traumatic years. Their experiences are unique and important, especially if they are willing to share it with the generations that follow. One of people is Ben Ernst of Nashville, Tennessee.

Ben seems, at a glance, like many men of his generation: he worked, married, and raised a son. But before building his adult life, Ben served the United States during World War II as a B-25 Mitchell bomber pilot and spent nearly two years as a prisoner of war in German Luftwaffe POW camps. Those experiences are not interesting to Ben, but all who have heard his story disagree.

He was born in 1918, the last year of the Great War, and had a relatively normal childhood despite surviving bronchial pneumonia when he was only a year old and being hit by a car when he was five. He grew up reading Boy Scout stories, Tom Swift novels, and other stories about the amazing World War I flying aces. When he was older, Ben joined the ROTC for three years and later, when he was 17, spent a year in a National Guard cavalry unit in Tennessee.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Ben was 23, but upon hearing the news he knew his responsibility was to his country. “I knew it was inevitable for me to join something,” he said. “I was military minded,”

Ben resolved to be a part of the fight and enlisted in the Army Air Corps. In his mind, that was the most exciting and revered branch of the military since its inception during World War I. They were the “Glamorous Heroes,” and that’s what Ben wanted to be.

In January 1942, Ben took his oath and was sent to flight school for a year of training. Based on his experience ROTC and the National Guard, he was made a cadet officer. Flying planes within six months of schooling, he was sent to B-25 school, followed by advanced training, where his flying abilities earned him the title of instructor.

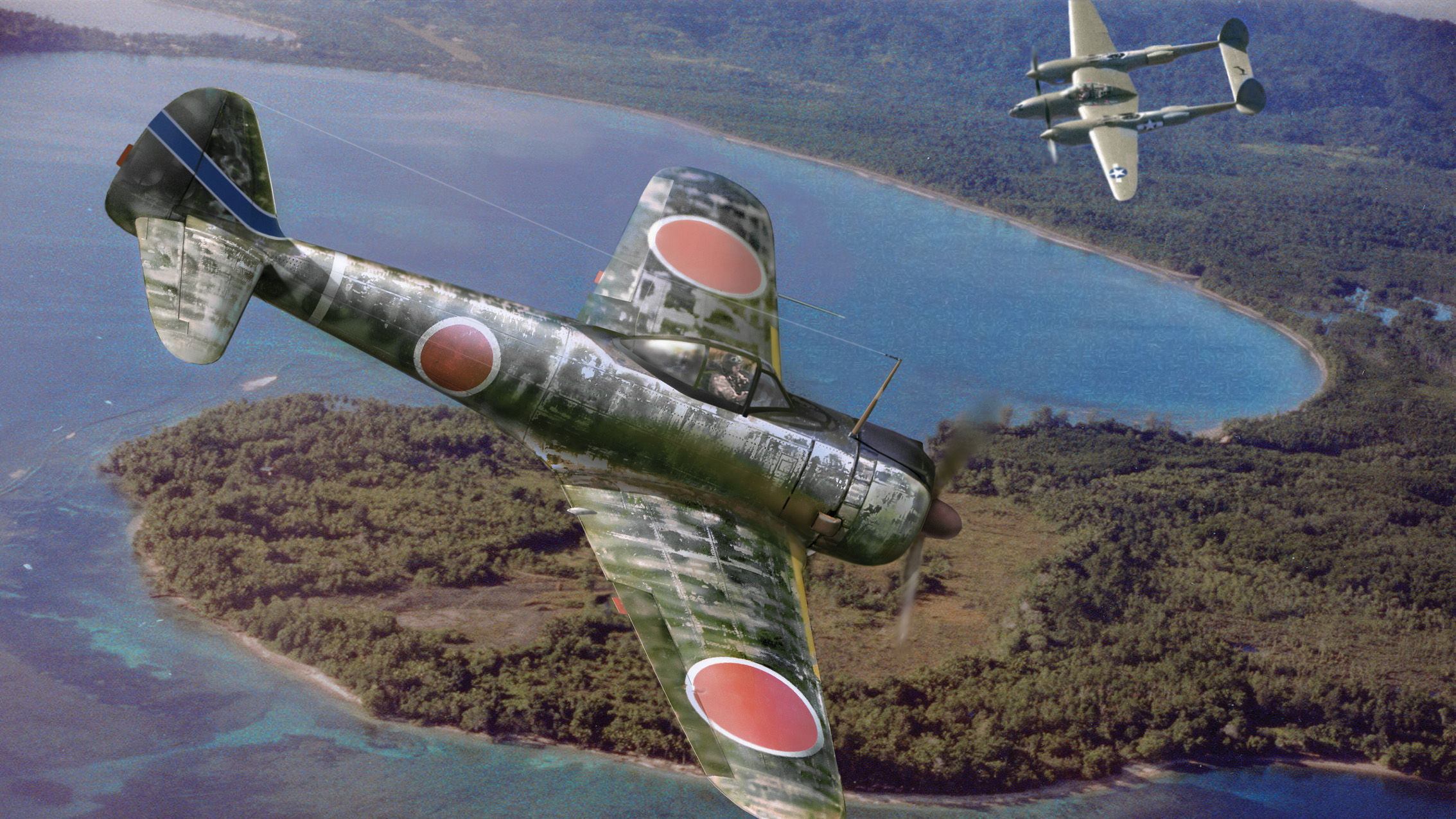

“Every bomber pilot wishes he had been a fighter pilot,” Ben said, chuckling. “We all wanted to be fighter pilots and fly P-51s. I never did get to, though.” He was bound to be a bombardier.

The twin-engine B-25, manufactured by North American Aviation in Los Angeles, California, and given the name Mitchell in honor of aviation pioneer Major General William “Billy” Mitchell, was a tough, durable airplane that could absorb a lot of punishment and still complete the mission. It is probably most famous as the type of plane that Colonel Jimmy Doolittle used in the April 18, 1942, raid on the Japanese homeland off the deck of the USS Hornet.

The B-25 had a crew of six, could carry up to 5,000 pounds of bombs, had a dozen .50-caliber machine guns, and a 75mm cannon on board. Its cruising speed was 230 m.p.h., and it had a service ceiling of 24,200 feet and a range of over 1,300 miles. A total of nearly 10,000 examples were built, with some 900 of them being used by the British Royal Air Force through the Lend-Lease program. Others were flown by the Royal Canadian, Free French, Soviet, and Polish Air Forces, and other allies.

Despite orders to remain in the States as an instructor, Ben pleaded to be sent to the front with the rest of his buddies. “Everyone else was getting a crew but me. I was not going to be left behind. So I went to the colonel and said ‘Colonel, I have to go out of here with my class. I cannot be an instructor.’ He said, ‘Okay,’ and they put together a crew for me.”

The men were sent to North Africa in early 1943 and Ben spent four months there with the Twelfth U.S. Air Force, flying multiple missions without issue, including participating in the initial invasion of Sicily in July 1943. Four nights after the invasion began, Ben’s plane was one of many sent to bomb the city of Palermo, Sicily.

Tragedy struck at 10 p.m. on July 13, when Ben’s plane, with its crew of six, was shot down over the Mediterranean Sea by antiaircraft artillery.

With a direct hit to the bomber, Ernst’s crew was lost instantly. Ben narrowly escaped, taking multiple fragments of flak in his arm, wrist, and leg. He recounted, “I got hit in the air over Palermo. And when you get hit, you didn’t pay attention to where the plane was, or how high you were. You just got out! So I hit the alarm button and bailed out.”

Ben tried to guide his parachute as he had learned during training, but with little success. He used the limited hang time he had to wrap his injured wrist with a handkerchief before landing in the Mediterranean. After hitting the water, he inflated his life vest, tore off his parachute, and began to swim.

For the next 18 hours Ben swam toward Palermo, visible miles off in the distance. Bleeding from multiple wounds, he convinced himself not to worry about sharks, even though the sea was flush with thousands. Surprisingly, he did not encounter a single shark, which was a true miracle in his mind.

Ben finally reached Palermo’s harbor after four in the afternoon the next day. The city had been destroyed the night before, but people still gathered on shore to see the man they had watched swimming all day. A little old Italian colonel drove down to Ben in a small, puttering car just as he was pulling himself out of the water. The colonel gave Ben his own overcoat for warmth and escorted Ben to his car.

As the two men were walking, a civilian brought Ben a small bowl of cherries. Dehydrated from the extensive swimming and accidental swallowing of salt water, the cherries were a cherished gift Ben devoured in only a few minutes. The sweetness of the cherries is still fresh in Ben’s mind.

The Italian colonel drove Ben to the German Luftwaffe headquarters and turned him over to a very intimidating German lieutenant. It was obvious that the Italian colonel feared the Germans, taking orders from an officer of lesser rank. The German lieutenant, using perfect British English, told Ben he was being taken prisoner and sent him to be held in a cave the Germans were using to house the men they captured.

Along with the other prisoners, Ben was kept in the cave for a few days before being moved to a small school for boys farther inland. Soon thereafter, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s U.S. Third Army forced the Germans and their prisoners to evacuate northern Sicily across the Strait of Messina to the “toe” of the Italian peninsula.

While the men were halted at a train station, waiting for an Italian invasion barge to carry them across the Strait of Messina Ben remembered, “It was my first encounter with the real British. There was a British colonel with a red beard on top of the invasion barge, wearing nothing but a G-string, male thong-type thing. And he was the one in charge of the prisoners! It was strange.” But Ben and the other prisoners continued to move and kept one step ahead of the advancing Allies.

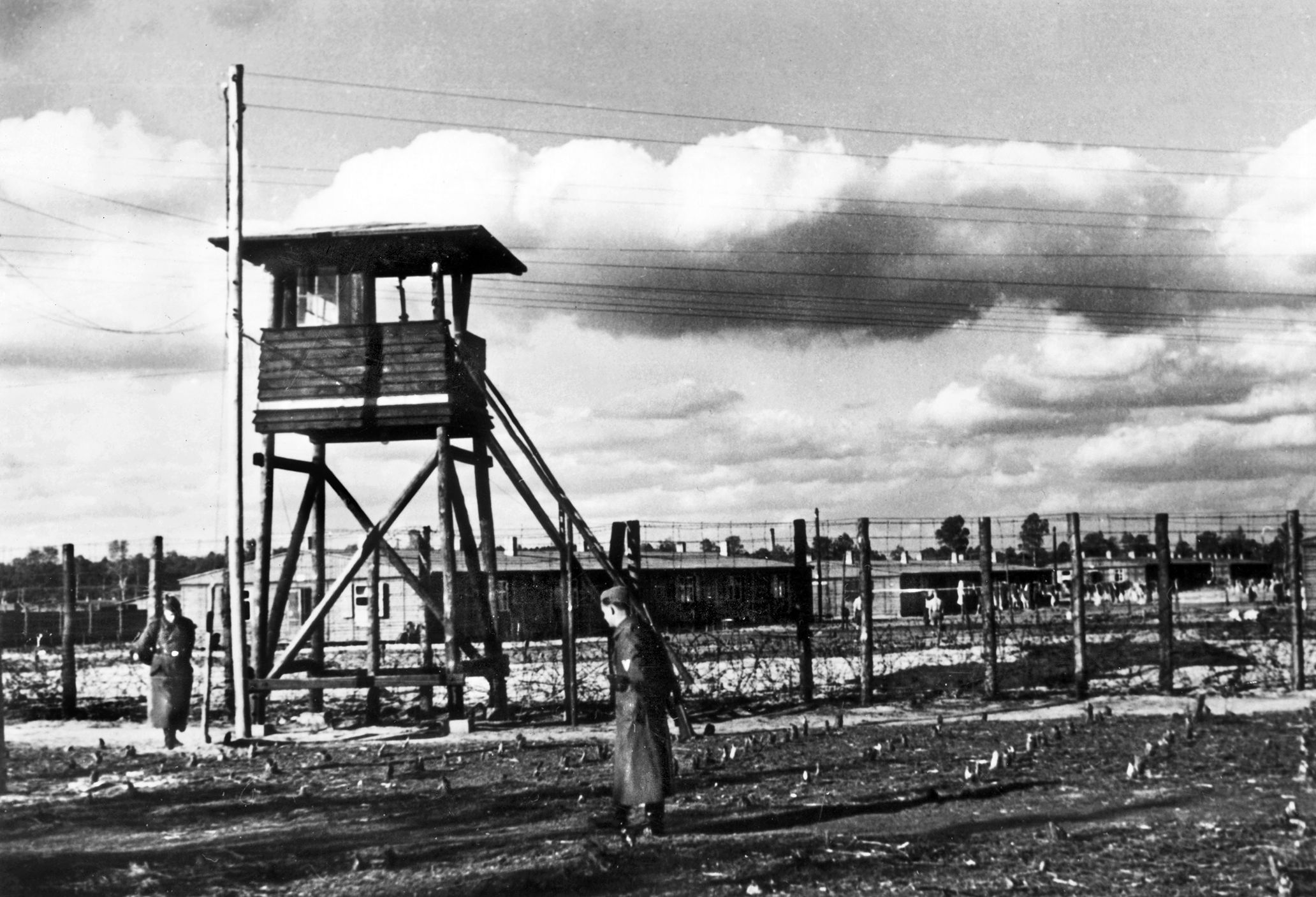

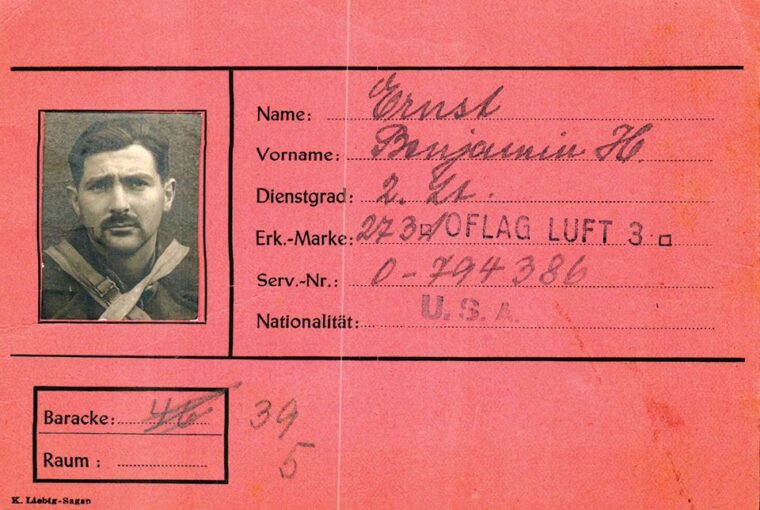

In September 1943, as the Americans and British armies continued their push up the mainland of Italy, the Germans continually moved their prisoners through Italy and through the Alps into Germany. Ben was finally moved to Stalag Luft III, the Luftwaffe-run POW camp for allied airmen located 100 miles southeast of Berlin near Sagan, Poland, made famous by the 1963 movie, The Great Escape.

Once in Stalag Luft III, one of six POW camps operated by the Luftwaffe, the prisoners were divided into compounds based on their nationalities, then housed in ramshackle barracks. The barrack interiors were lined with bunks and contained small stoves the men used for heat and cooking. The prisoners called themselves “kriegies”derived from Kriegsgefangene, German for “prisoner of war.” The guards were the “goons.”

With a dozen or more men in each barrack, there was no privacy, but that was never an issue. The men did everything together. They developed a bond only few people have come to understand—a bond that outlasted the war and created life-long friendships.

Prisoners also got to know the men in the other barracks during the daily morning roll call, but the majority of the day was spent in their own barracks idling the day away—reading, playing sports and chess, cooking, and smoking cigarettes. Nighttime bombing missions caused some excitement when they got close to the camp. But according to Ben, “It really was a drab, dull life. Every day was the same and so were the people.”

Ben says the worst part of his time in the camp was the food. The war had caused mass food shortages across Europe, and even though the Germans tried to feed their prisoners, the rations were so small the men were always hungry. The scarcity of food inevitably led all prisoners to lose large amounts of weight. Ben, for example, lost 40 pounds during his 23 months as a prisoner. To stretch the rations, the Germans primarily fed the prisoners different soups and stews.

In order to survive, the men relied heavily on Red Cross food parcels, especially when the German-supplied meals seemed inedible—a thin watery soup flavored with grass or rotten vegetables and bits of spoiled, maggoty meat.

“One day a soup came in to the barracks and it had eyeballs floating, along with little bones and some skin.” Ben still cannot say what type of rodent was used in the stew but he believed it to be either squirrel or rat. Either way, in those days he forced himself to eat everything in the bowl, but he could never bring himself to eat the eyes. “From that day forward, we called stews of that nature ‘Seeing Eye Stew’ after Seeing Eye Dogs. We had to laugh it off.”

When the food was just too gross to eat, the men worked together to dispose of it down the drains. If the Germans discovered that the food had not been eaten, they would deduct rations from all future meals. Since food was already so scarce, the men did everything they could to prevent losing more. As a result, many men, including Ben, took up smoking cigarettes. They claimed the cigarettes helped curb their appetites, allowing them to better endure the gnawing hunger pains.

Ben still remembers the winters in camp. The frigid temperatures lasted weeks, often dipping well below zero. Despite the Germans’ attempts to supply coal and wood for burning in the stoves, the barracks were always cold, often making it impossible for the men to even bathe. Inedible bread was even used as a source of fuel but the chill never went away.

Ben does have one proud memory from his days as a POW—when he helped build a library for the camp. The men were already receiving 10-pound packages of books each month. While many of the books never made it to the prisoners, the ones that did were shared around the camp until they fell apart.

Needing a break from the monotony and recognizing the need, Ben and a few other men requested that the commandant, Colonel Friedrich Wilhelm von Lindeiner, allow them to have a library to make sharing the books easier for the prisoners.

The Germans agreed, and provided a room lined with rows of bookshelves. The books in the camp were collected and arranged in the new library. The men used cigarette boxes to make index cards for each book and, when the books’ bindings fell apart, the Germans supplied material for the men to rebind the books themselves.

Ben worked in the library his last year at Stalag Luft III and, relatively speaking, “enjoyed” his time there. He was extremely thankful for the change in his daily routine because the time he spent in the library helped the last months in camp pass by a little quicker. And the books helped the POWs “escape” from their situation, at least temporarily.

While prisoner life was not easy for the men at Stalag Luft III, the inmates were thankful, even happy, to be in the German Luftwaffe-controlled POW camp. After all, they were alive, away from the front lines, and treated relatively well by their captors. The men always hoped for their liberation but never stopped counting their blessings for their relative safety as prisoners. Ben says they were fortunate because they were handled with respect and dignity.

According to Ben, there was a drastic difference between the German military and the German SS and Gestapo. The German military comprised enlisted men serving their country, just like American infantry. The German SS and Gestapo, however, were responsible for the atrocities against Jews and other people they deemed as “undesirables.”

It was not until after the war that the men learned a concentration camp had only been 50 miles from their own POW camp. Many of the prisoners were just thankful they were dealt with humanely, unlike the men being taken prisoner in the Pacific by the Japanese.

The night of March 24-25, 1944, marked a turning point in the camp—the night of the “great escape” from Stalag Luft III. The escape had been planned for nearly a year, with 600 prisoners contributing to the effort—all so that 200 prisoners could break out of the camp’s British North Compound. Forged passports were created and blankets and military uniforms were turned into civilian clothing by men who had been tailors before the war. Three tunnels were dug from beneath barracks to beyond the perimeter fence, giving the men a better chance to escape.

But, on the night of the great escape, multiple unforeseen obstacles kept most of the men from reaching freedom. As a result, instead of 200, only 76 men were able to flee the compound before the alarm was sounded, and that freedom was brief—only three made a successful escape.

After Hitler was informed of the breakout, he flew into one of his usual rages, demanding that 50 of the 73 recaptured prisoners be executed as a lesson to any other POWs who might be contemplating escape.

The day after the escape, the remaining prisoners were assembled for roll call and an announcement was made: 50 of the 76 escapees “were killed” during the mass breakout. According to Ben, “Everyone was wondering why we were out there. And I made a smart remark. I said that ‘they were going to shoot every tenth one of us.’” Thankfully, he was wrong. The repercussions were still dire, however.

Fifty men were taken, two at a time, out of the camp and shot. The bodies of the dead escapees were cremated and the urns containing their ashes returned to the camp. The British prisoners built an impressive monument to their memory in the Stalag Luft III cemetery, which remains to this day; the small cemetery continues to be maintained by the local Polish people. The British investigated the killings after the war and a 1947 military tribunal found 18 Nazi guards guilty of war crimes—13 were executed.

Of those escapees who were recaptured, most were sent to a more secure prison, or as Ben explained, “The men were sent to a bad boys camp to spend the rest of their days in captivity.”

The only change made at the camp was in the leadership. The Gestapo was put in charge of running Stalag Luft III and the German commandant, Colonel von Lindeiner, who was previously in command, feigned mental illness to avoid being imprisoned for having the massive breakout take place on his watch. (He was wounded by the Soviets during the defense of Berlin and spent two years as a British POW. The German higher command was also replaced, but the day-to-day treatment of the prisoners did not change.)

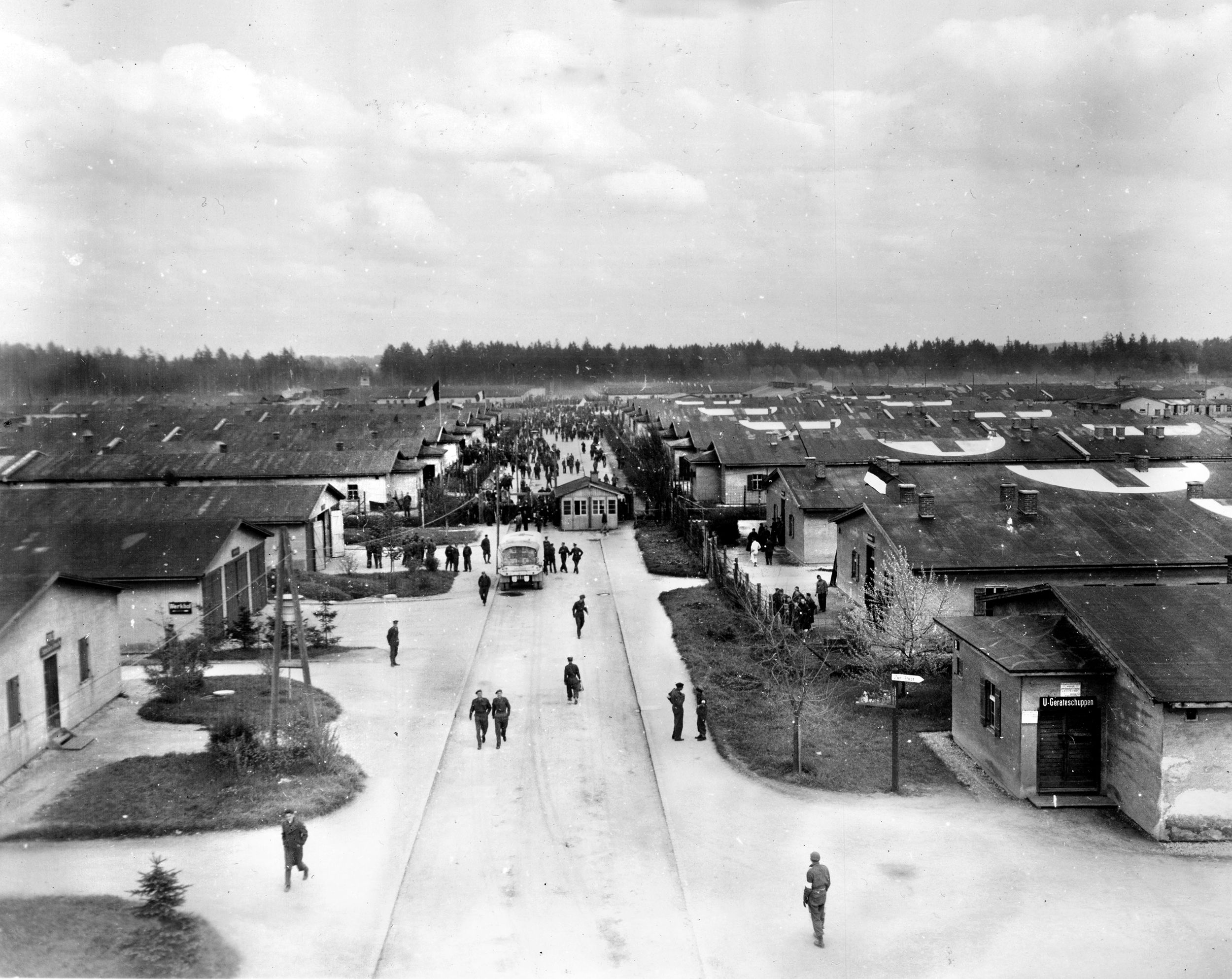

After the “great escape,” breaking out became more difficult and dangerous but attempts continued. In the confusion spreading across Germany as the end of the war approached, the kriegies at Stalag Luft III were moved to Stalag VII-A, near Moosburg, northeast of Munich, on January 27, 1945. First on foot, and later hauled by boxcars through three wintry nights and days, hoping to avoid being bombed and strafed by Allied aircraft, the

11,000 frozen and starved POWs finally arrived at their new home.

But Stalag VII-A was no resort. It was Germany’s largest POW camp. More than 100,000 prisoners representing all nationalities (there were 27,000 U.S. and British POWs) were crammed into vermin-infested barracks; 500 men were stuffed into buildings that had been overcrowded with 200. Unknown numbers of escape plans were still being secretly discussed among the prisoners.

When it became obvious that the end of the war was near, even the most ardent advocates of escaping decided to wait it out. On April 28, 1945, Maj. Gen. Charles H. Karlstad’s Combat Command A of the 14th Armored Division (the same division that had liberated the POW camp at Hammelburg three weeks earlier) had advanced 50 miles and was approaching Moosburg when a small party was seen approaching in a car displaying a white flag.

The party included a British and an American officer and a representative of the Swiss Red Cross, along with an SS major carrying a written proposal for surrender of the camp. Until that moment, U.S. forces had not even known that a POW camp was in the vicinity. They were escorted to meet with Karlstad and a discussion about the proposal ensued between the SS major and Karlstad.

Karlstad radioed the division commander, Maj. Gen. Albert C. Smith, about the situation and asked for instructions. Instead of negotiating an armistice, Smith told Karlstad to tell the SS major that the only answer was immediate and unconditional surrender. When that was not forthcoming, Karlstad’s men went into action.

Meanwhile, the two officer prisoners who had accompanied the party to CCA headquarters returned to the camp to inform the POWs that an armored unit was coming to their rescue and to take cover in case fighting broke out.

CCA began its attack on German troops in the Moosburg vicinity, with its primary mission the capture of the bridge over the Isar River. The SS put up a stubborn fight for the bridge to the east of the town, even destroying it with demolition charges before the Americans could cross.

The fight did not last long, and soon the overmatched SS were giving up their positions. CCA men reached the POW compound on April 29. An official account of the event said, “Scenes of the wildest rejoicing accompanied the tanks as they crashed through the double 10-foot wire fences of the prison camps. There were Norwegians, Brazilians, French, Poles, Dutch, Greeks, Rumanians, Bulgars. There were Americans, Russians, Serbs, Italians, New Zealanders, South Africans, Australians, British, Canadians—men from every nation fighting the Nazis. There were officers and men. Twenty-seven Russian generals, sons of four American generals…. There were men of every rank and every branch of service, there were war correspondents and radio men.”

General Patton, along with a crowd of ranked officers, entered the camp later that day in order to assure the POWs of their safety and freedom. Luckily, Ben and a couple of buddies knew where General Patton and his men were headed inside the camp, and ran to where the general would be. As Patton walked by, he stopped and saluted each man as he passed. Ben still remembers when Patton saluted him personally and how proud he felt at that moment. Right then, Ben knew he was finally safe and would soon be going home.

However, the men in the camp were not immediately released. Since the various armies had to make arrangements to evacuate their soldiers, the men were kept in the camp for a few more weeks. When the war in Europe finally ended on May 8, 1945, Ben was still at Stalag Luft VII-A. Two weeks after liberation, Ben was finally sent to France and then shipped back to the States.

After returning home, Ben stayed in the Air Force until 1950, leaving only two months before the outbreak of the Korean Conflict. Once retired from the military, he worked for his father a short time before building his own mortgage company, and later spent a spell working for the government.

In 1948 Ben married Dorothy “Dot” Sanders from Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Ben and Dot lived quite happily and in 1956, they had a son, Benjamin Jr., who enjoyed an incredibly close relationship with his father all of his life.

Ben’s experiences as a POW taught him a great deal. Ben said, “After the war, I never truly got upset.” He had always been an easy-going kid growing up, but his time as a prisoner taught him to be thankful for every day he was alive and safe. He also learned incredible patience from his experience.

Ben Enrst passed away on September 10, 2015, at age 97. He survived bailing out of his plane and 23 months as a prisoner, enduring the blistering cold winters and severe food shortages. But he was still able to make the best of his situation, holding on to hope, even in the worst of times. Since his return from the war, he always held the firm belief that nothing could be bad after his time as a prisoner.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments