By Bruce Petty

Alan George was born in 1918 and was fourth-generation New Zealander. His great grandparents arrived in New Plymouth in 1841 from Cornwall, England, aboard the 506-ton ship Oriental. They were among the early arrivals to first settle in the area and hack a living out of what was then native bush.

The Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) was formed in 1923, and more than 90,000 men and women have served in it since then. It reached its peak strength in 1944 with 45,000 individuals serving. Those flying in Royal Air Force (RAF) bomber squadrons during World War II initially had to fly 25 sorties. This was later raised to 28 and then 30. Those who survived their first tours were given ground time, usually as instructors, before heading back into combat for another tour of at least 20 sorties. Pathfinder crews, on the other hand, being volunteers, were required to do up to 40 sorties, and some did many more than that. Pathfinders, as the name suggests, went in ahead of the main bomber force and lit up the targets with incendiaries.

George, along with a number of other New Zealand airmen, set sail for England via Fiji and Canada and then sailed in a convoy out of Halifax, Nova Scotia, in April 1941. He was first assigned to RAF No. 115 Squadron as a second pilot and then soon after as first pilot flying a Vickers Wellington bomber, a plane he described as slow, with poor altitude capabilities, and easy to shoot down. His first mission as a plane commander in a Wellington bomber was more than a little exciting. On a mission in October 1941, one of his engines was shot out. However, he forced his crippled bomber on, dropped his bombload, and made it back to England, where he made a forced landing short of his base. For this, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal.

Later, on a mission over Essen, Germany, in August 1942, George was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for bringing his wounded aircraft back to base after dropping his bombload over the target.

RAF No. 139 Squadron formed in June 1943, flying an all-wood aircraft called the De Havilland Mosquito. The Mosquito was a two-engine, British-built aircraft, designed and built by Charles de Havilland. It was an aircraft the RAF originally showed no interest in. Likewise, other aircraft designers ridiculed it as unworkable. De Havilland was told, “Nobody makes aircraft out of wood anymore.” However, in time and with England desperate for anything that could fly, de Havilland won over the skeptics. By the war’s end the Mosquito proved to be one of the most versatile and best loved aircraft of World War II.

Unlike the larger bombers of the day, the Mosquito was originally designed to carry no armament and only two crewmen, the pilot and the navigator-observer. Its main defense was its speed. At almost 400 miles per hour, it could outrun any German fighter except the later jets. In fact, while on one Pathfinder mission, George’s Mosquito was attacked from behind by a Messerschmitt Me-262 jet fighter. He avoided destruction by diving away at the last minute as the bullets and the jet shot menacingly over him. The Mosquito’s speed and rate of climb had everything to do with the Rolls Royce Merlin engines that were installed in it. It had one of the best, if not the best, liquid-cooled aircraft engines to come out of the war.

George flew 73 missions over Germany and France during the war, including the last mission of the war in Europe against the German port city of Kiel. By the end of the war, he had been decorated twice, had a private interview with Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris, the controversial leader of Bomber Command, and was invited to Buckingham Palace to meet the King of England.

As a volunteer member of a Pathfinder squadron, RAF No. 139, he was one of the lucky few to survive the war. Four out of five members of his squadron did not. In fact, Bomber Command, which numbered roughly 125,000, suffered 55,500 killed, more than 8,000 wounded, and another 9,800 taken as prisoners of war.

Like most survivors of the war, George married and raised a family. He and his wife of 65 years raised nine children. After 16 years in the military, George left the RNZAF to take over the family farm outside of Mania in South Taranaki on North Island and farmed well into his 80s. At the age of 95, he still lived in the house built in 1912 that his family bought in 1920. He passed away only recently. Until his last days, his memories were vivid, and he shared them with the author some time ago.

“If you look in the phone book in New Plymouth you will find about 40 Georges; we are all related. I am the product of a second marriage. My father lost his first wife, and he married my mother. He had two grown sons when they had me. I was the only product of the marriage. My father was a carpenter and I was two years old when he bought this farm in 1920. As a child, I was always captivated by anything that had to do with airplanes.

served as an instructor training new pilots.

“I used to spend hours as a kid watching birds fly, and I used to try jumping off heights, trying to fly. Anything I could find out about airplanes captivated me. I took any spending money I had and went to the aero club at Hawera and bought a ride; I was so captivated by flight. Ian Keith was one of my instructors; and another one was a man called Dan Lethbridge. Then came the war, and I immediately enlisted in the RNZAF.

“One thing my father did for me—he gave me a good education—and in the early stages of the war you had to be educated up to a certain standard, so I was one of the first to be accepted into the New Zealand Air Force. I did my training in New Zealand. I went first to Levin for ground training, and then New Plymouth for elementary training in Bell Block, a grass field north of New Plymouth. I was always determined to prove myself. I was always trying to excel. That drove me, and as a result I was the first in my class to solo; and all through my flying career that motivated me. Most of my compatriots are dead. Do you know how many people we lost in Bomber Command? I’ll tell you: We lost 55,500 killed.

“We were the first boatload from New Zealand to embark for England after the war started. We left Auckland in April 1941 aboard the Awatea. It was lost later in the war in the Mediterranean. It was a beautiful ship. We went from Auckland to Fiji to Vancouver. At this stage, America was not in the war. From Vancouver, we went on the Canadian Pacific train to Halifax; five days and five nights to cross Canada. You can imagine how that impressed me, coming from this small country.

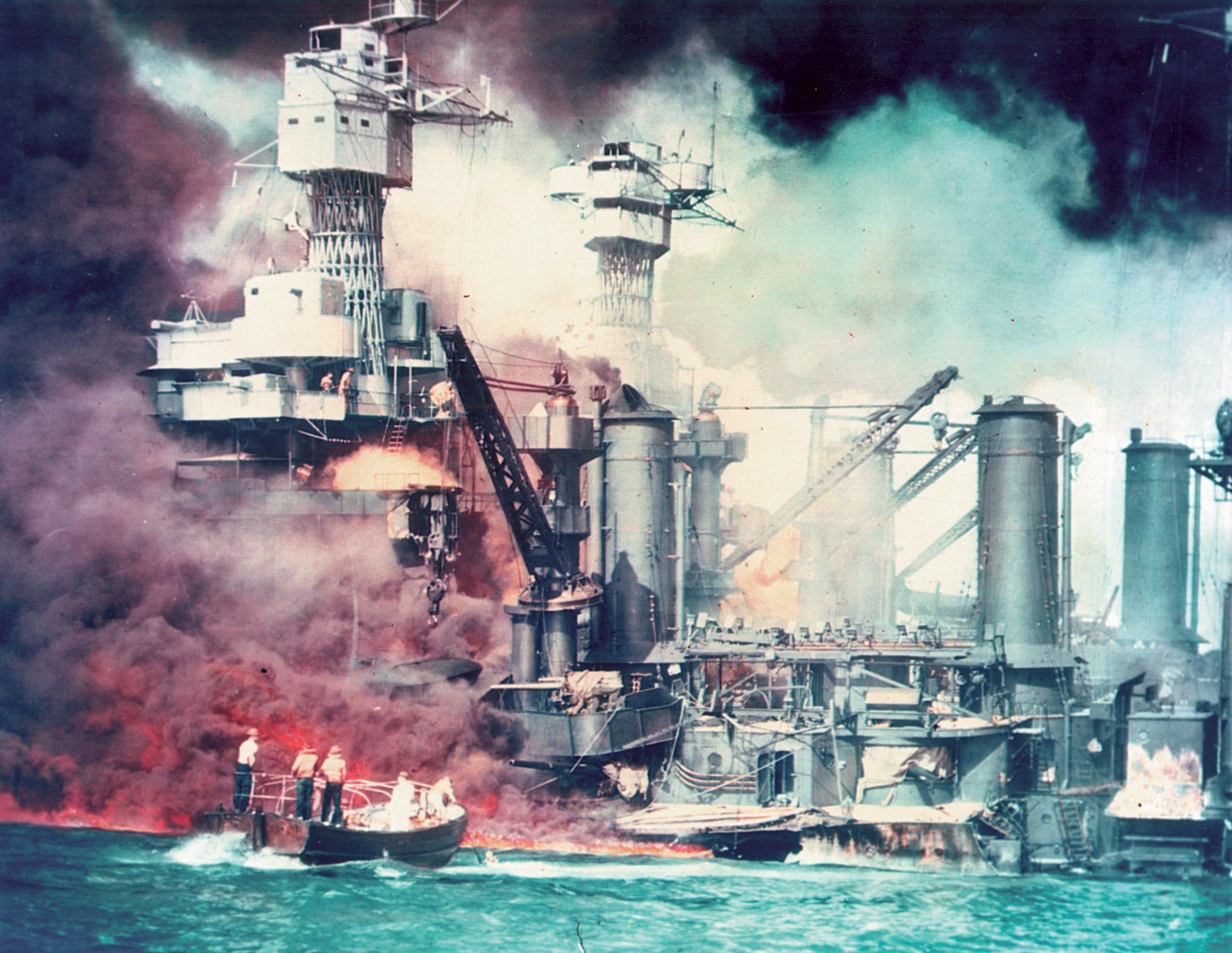

“We arrived in Halifax, and there we were stuck for a fortnight. The Hood, if you know your history—a British battleship [actually a battlecruiser], which was old and under-armed—was sunk by the German battleship Bismarck. The Bismarck was out there, so we had to wait until the British Navy got her. We were then rushed onboard a ship, went up to Iceland, went onto another ship, and arrived in Scotland. The ship we boarded at Halifax was an armed merchant cruiser. The ship we boarded in Iceland was a converted Irish Channel steamer. It was a hell ship, infested with rats.

“In Scotland, we went by train to Bournemouth. We were the first New Zealand airmen to arrive there after the war started. I was with another New Zealander, Jock Hunter from Hawera. He didn’t last very long; he was flying a Sterling [Short Sterling bomber]—blew up at takeoff.

“We went up to a place called Lossiemouth, Scotland; it was a big flight training school for Bomber Command. Okay, so training finished, and I will always remember the instructor saying, ‘Okay, your training is finished. You are now going to an operational squadron. You have been flying to the west over the Atlantic. Now you are going to fly to the east over Germany, and people will be firing at you. You are going to hear gunshot. This will be where your first test of manhood comes in. Some of you will die. This is where you are going to find out what you are made of.’

“I was posted to 115 Squadron—Wellingtons. I did my first operations as a second pilot. You had to do some ops as a second pilot. Then when you had proven your worth you were made a captain or first pilot. I was lucky. Like I said, I was always trying to excel. I was driven. I had it built into me that I had to prove myself.

“I was given my own crew after only several second-pilot trips. On my first mission I was given a target outside of Paris—Poissy, to bomb a motor car works. My Wellington was unusual in that it had Merlin motors. Most Wellingtons had Bristol motors. We caught some antiaircraft fire in one of the motors, and it caught on fire. We had to force land on the south coast of England.

capital of Berlin during a raid by 27 De Havilland Mosquito bombers conducted in September 1944.

“The Wellingtons, with a full load of bombs, were lucky to get above 12,000 feet. Usually you were bloody lucky to get above 10,000 feet, and that was like shooting ducks for the Germans. With the Mosquito, we could get a load of bombs up to 30,000 feet. A Mosquito could carry one bomb of 4,000 pounds and take it to 30,000 feet in 20 minutes. It was the most remarkable plane ever built, and that absolutely had to do with the Rolls Royce Merlin engine!

“That was just the start, and then I progressed through a series of raids until I got to my 33rd mission. You had to complete 30 missions and then you went on rest, usually as an instructor. Then, after a period as an instructor, you were brought back to a squadron to do another series of missions. That theoretically gave you a total of 50 missions, if you lived. We lost planes every night we went out.

“Anyway, I finished my first tour and became an instructor and instructed for quite a while. I then put in an application to go to RAF Staff College; I wanted a bit more education. My application was approved. It was a class for senior officers. I wasn’t a senior officer, but I got approval because I had distinguished myself in operations. That was several months of work. Then having graduated, I was suddenly sent back to New Zealand because the flight training schools there had expanded and they were training new pilots right, left, and center. At one camp outside of Blenheim they went on strike. They weren’t allowed to call it a mutiny. That was 1943. It was a ground training camp. I had to straighten the place out, which I did. I kicked a few blokes out and instituted some discipline. I found out what the cause was. It was inefficiency, dirty cookhouse, bad rations…. I straightened the place out without punishing anybody. Then I told everybody, “Okay, obey the rules or you’re in the army!”

“That was all that was needed. And as a reward, I was sent straight back to England, which is what I wanted. By this time, the Americans were in the war, and they wanted pilots to go to the Pacific. I didn’t want to do this. I wanted to go back to the Royal Air Force, and my wish was granted.

“I went back to England, and this is where it becomes interesting. I went into a Mosquito squadron and volunteered for Pathfinders. Pathfinders were an elite section of the Royal Air Force. These were men who had distinguished themselves in a first tour. You had to have a first tour to be accepted, and the first thing you had to do was make out your will. The commanding officer told us four out of five of you will die, so go and make your will. If you weren’t ready to accept that you went back to Main Force.

Air Force is shown in flight in February 1944.

“The squadron I went to was No. 139. Our main objective was Berlin. That was [British Prime Minister Winston] Churchill’s idea. The Germans had bombed the hell out of London, and Hitler boasted that Berlin would never be touched. It was farther away and difficult to hit. It was the most highly defended place in the whole of Germany, and Churchill gave instructions to “Bomber” Harris that Berlin had to be bombed! No. 139 Squadron was one of the squadrons given the task of bombing Berlin, so we went night after night. We did two nights, and then had a night off; two nights on, one night off. We were set a target of bombing Berlin for 50 nights in succession—this one squadron.

“As Pathfinders, we had to go in and mark the targets with incendiaries. We got to 30 missions, and we were stopped. It was a forced rest because of the stress and the losses we were taking. It was a terrible task. I did, I think it was 20 trips. That is the story of 139 Squadron. We bombed Berlin night after night; two nights on, one night off. That is how that book, Night After Night, was written.

“We used to talk about the following in the crew room: We all had the same fear. We didn’t want to know when we were going on our last mission. It was a horrible thought, “Oh, only one more mission. Will we make it?”

“By this time I was up to over 70 ops. I did 40 Pathfinder trips in that squadron—night after night, night after bloody night. Two on, one off.

“Vivian Broad went with me on all of my missions, all 73. He was my wireless operator on Wellingtons and my navigator-observer in Mosquitos. We became good friends. He was an Englishman, and I went home with him on leave and stayed at his parents’ house. While I was in New Zealand, Vivian used his time to train as a navigator-observer, and when I volunteered for Pathfinders so did he. So we stayed together throughout the war. He and his wife went to the Mexico Olympics in 1968, and then they came to New Zealand to visit us. He was about 10 years older than me. He’s dead now.

“I remember the commander called us in and said, ‘Right, this will be the last time you fly. Get home tonight and you will be through the war.’ And that was the night before the Russians entered Berlin—April 20, 1945. Thankfully, we didn’t lose any planes that night!

“They called us in again the next day and said, ‘Sorry boys, but one more.’

navigator-observer Vivian Broad smile for a photographer. Alan George completed dozens of Pathfinder missions with Broad flying alongside.

“One more! We had to go to Kiel! After that my flying days were over. Of all the New Zealand pilots I went over to England with, only two or three survived the war. It’s not good to go there. Death was so prevalent; we lived for the day. We never planned for the future; it was unlucky. Tomorrow never came. Every morning you would see a new face at the breakfast table and think, ‘Is my turn coming?’

“The last thing you did before you went on a raid was make sure your bed was made and that you had written your last letters home, and you looked at your bed as you went out the door and wondered, ‘Will I sleep in it tonight?’

“The North Sea has thousands of aircrew in it. They fell in it on the way home after being shot to bloody ribbons. We would lose dozens every night.

“I flew 73 missions. Very few pilots flew more than that. I was shot down, chased by German fighters…. I had all sorts of mishaps, but I am still alive. Because of my war experiences I developed a very hard exterior. You had to. It was almost as if death was inevitable, and your one wish was that it would be quick.”

Bruce Petty is the author of five books, four of which concern World War II in the Pacific. His latest is New Zealand in the Pacific War. He is a resident of New Plymouth, New Zealand.

Good morning Bruce,

Your story of my father’s service in the RNZAF and RAF Bomber Command is devalued by unnecessary exaggeration and untruth. I have written to you about this before. Why do you continue to publish it unamended? A Ms Melanie Reid who is also a journalist similarly promulgates distorting coverage claiming in defence thatf she is only publishing what she has been told.

I request that you do some research and sort the facts.

My father is not able to defend his own record.

Sincerely

Cris George

As a History buff by education and avocation, I have continually come across “facts and reported” experiences that were later amended with more or corrected information. In many instances, this was not done with malicious motives but simply because of inevitable distortions during the stress, confusion and fog of war. The deliberate coverups and outright lies were not as common and many were uncovered later when time and motivation permitted.