By Eric Niderost

It was late afternoon on June 24, 1340, when the English fleet arrived off the Flanders coast, just short of the Zwin estuary, reputed to be the finest harbor in Europe. King Edward III was aboard his flagship Cog Thomas Beauchamp, looking at the distant shoreline and noting every detail with the keen and discerning eye of the professional soldier. Flat and almost featureless, the shore was a sandy streak across the horizon. The monotony was relieved only by the few patches of wind-buffeted grass and stunted shrubs that clung to the dunes.

But suddenly a forest came into view, a cluster of trees that seemed even taller when contrasted with the flat sand dunes that surrounded it. On closer inspection, it was not a forest at all, but the masts of hundreds of ships that were blocking the entrance to the estuary. The king was not surprised, for this was the quarry for which he had been looking. Nevertheless, he wanted confirmation, so he turned to Cog Thomas’ master, who was dutifully standing by his monarch’s side.

“What ships are those?” the king asked, receiving the reply he expected: “Sire, they are [French] sent here by the French king,” replied the ship’s master. “They burnt Southampton and took your great ship the Christopher.” Edward was pleased by the response. Already a seasoned warrior on land, the coming fight would be his first experience at sea. “Ah, I have long wanted to fight with the Frenchmen,” he said, “and now I shall fight some of them by the grace of God and St. George, for truly they have done me many displeasures, that I may be revenged.”

The English king was a striking figure as he stood in armor with his legs braced against the gentle, yet persistent, swaying of the ship as it cut through the wind-dappled waters of the English Channel. His beard and mustache were neatly trimmed, and he was wearing a conical bascinet helmet that featured a curtain of mail riveted to it that hung down and gave protection to the neck and shoulders. This was a transitional age when mail was gradually giving way to plate armor.

But what was most noticeable was Edward’s surcoat, a colorful tunic that boldly displayed his coat of arms. The design featured three lions, which in formal heraldry actually were leopards, on a red field. But those lions were quartered with the traditional lilies of France. Here, in tangible form, was the outward expression of Edward’s political quest. He intended to assert his claim as the rightful king of France.

To the medieval mind “may God defend the right” was no empty slogan, but a day-to-day article of faith in divine power. For Edward, his first sea battle would be a trial by combat. If the English king’s cause was just, he reasoned, God would grant him victory.

This seemingly quixotic quest for a foreign throne had its roots in the death of his uncle, Charles IV of France, who passed away in 1328 without leaving a direct male heir. The closest living male relative was Edward, through his mother, Isabella, Charles’ sister. In that male-oriented age no one seriously considered a woman as sole ruler, especially in France. But could she be a bridge that would make her son a prime candidate? Opinions were divided. While the lawyers argued, the magnates of France took action by choosing Philip of Valois. Philip was the late monarch’s cousin, so at least on paper Edward had the stronger claim. The idea of candidacy through a woman was a stumbling block, but probably not insurmountable.

Feudalism was a system of land tenure by which, at least in theory, a person of higher status granted territory to one of lower status. The lower-status individual became the grantor’s vassal, owing him loyalty and service. Feudalism depended on hierarchy and a system of mutual duties and obligations between suzerain and vassal; one’s nationality was of secondary importance. Nevertheless, the spirit of nationalism—of allegiance to one’s culture, ethnic identity, and language—was increasing. Edward was probably rejected because he was a foreigner. In the 1330s, there had been some half-hearted attempts to advance Edward’s candidacy to sit on the French throne, but eventually the matter was dropped, at least for the time being.

The contest for the French throne was only the latest expression of a rivalry that dated from the Norman Conquest in 1066. Edward III was, like his predecessors, the Duke of Aquitaine, a fertile region in southwestern France. When Duke William X of Aquitaine had died in 1137, his expansive duchy went to his 15-year-old daughter Eleanor. When she subsequently wed the French dauphin, her inheritance fell under the direct control of the French crown. But when her marriage ended in annulment, she once again received control of the duchy. Her marriage to Henry of Anjou and Normandy in 1152 transferred control of Aquitaine to the English crown when Henry ascended to the throne two years later. As Duke of Aquitaine, King Henry of England was a vassal of the French king. The fact that he owed his loyalty and obeisance as a vassal to the Gallic monarch implied an inferior position.

When a vassal formally took possession of his lands, he first had to acknowledge his liege-lord’s generosity by paying him homage in a formal ceremony. A teenaged Edward of Windsor reluctantly agreed to pay homage in 1329, two years into his reign as King of England, but offended King Philip VI of France by wearing a crown and carrying a sword. When Philip demanded Edward go bareheaded and unarmed, as befit a humble vassal, Edward refused. The matter blew over, and there was relative peace for a few more years, but it was obvious the two kingdoms were on a collision course over Gascony, a geographical term that was often used interchangeably with Aquitaine.

The English had other grievances, too. One of the most critical was the matter of Scotland. Scotland and France had first entered into a treaty of mutual support in 1295 that would become known as the Auld Alliance. Scottish King John Balliol, who needed allies given that his relations with England were rapidly deteriorating, had approached the French for the purpose of enlisting their aid. It was the beginning of strong military and political ties between the two countries.

The initial agreement between France and Scotland was renewed in 1326. The Franco-Scottish pacts set forth—open for all to see—that the two countries would help each other against England, which was their mutual neighbor and frequent foe. If the French invaded by sea and the Scots by land, then English forces, caught between these two forces, might well be defeated in detail.

Gascony would prove to be Edward’s Achilles’ heel, and Philip well knew it. It had been the policy of French kings for more than 100 years to consolidate their holdings, in effect uniting the patchwork quilt of feudal territories under the real, not nominal, rule of the French crown. That meant the French crown had to seize territories when opportunities arose; if not, it had to at least nibble way at coveted lands in its corner of continental Europe until it controlled all of them. Philip’s obvious goal was to take over Gascony by whatever means he had in hand.

For his part, Edward was just as determined to hold onto his continental possessions. Wool and wine were the two chief pillars of English prosperity in the 14th century, and the latter came from Gascony’s rich soil and abundant vineyards. Edward III was perpetually in debt, but the revenues he received from the wine industry kept his government afloat and functioning. The king’s income was only about one-third that of his French rival, roughly between 18,000 to 33,000 pound a year, in addition to 13,000 pounds from Gascony. As the figures demonstrate, the wine trade was often nearly equal to all other sources of the Crown’s income combined; the loss of Gascony and its imported wines would be a severe blow to the English economy.

It was therefore inevitable that a war would commence after King Philip assembled a Great Council in May 1337, that declared Edward was in breach of his obligations as the French king’s vassal. As a result of the English king’s alleged transgressions, his lands in Gascony were forfeit, and he was no longer Duke of Aquitaine.

Now that the die was cast, both Edward and Philip sought allies. Edward found his in the semi-independent Flemish mercantile towns, such as Bruges, Ghent, and Ypres. They were natural allies because these cloth-producing centers needed English wool for their hundreds of looms. Edward offered each of them generous commercial privileges, including free trade for Flemish cloth in English markets.

The pact was signed in late 1339, but the Flemings demanded one thing in return: They wanted Edward to declare himself the king of France. The residents of the Flemish cities despised Philip of Valois but had no wish to be branded traitors and rebels. The French king was their nominal overlord, and they could more easily save face if they merely switched allegiance to Edward. Edward may have had no real desire to be king of France; but the need for allies, as well as political expediency, ultimately forced his hand.

The French decided to strike the first blow of the war at sea. Philip knew of Edward’s financial difficulties, his perpetual need for money, and decided to wreck the English economy by raiding English ports and disrupting its maritime trade. England depended heavily on revenues gleaned from the wool and wine trade. If Philip were to disrupt these crucial revenue streams, he believed he could cripple the island nation. English penury would overwhelm English pride, and Edward might sue for peace.

King Philip ordered Nicholas Behuchet, his new Admiral of France, to begin the sea campaign early in 1338. A French fleet descended on Portsmouth, which lacked a protective wall and was taken by surprise. The French ruthlessly sacked the vulnerable town; in the process, they either slaughtered its inhabitants without mercy or took them as slaves. The French raiders torched the town’s homes, stores, and docks until there were nothing left but smoking ruins.

A Gallic raid at Walcheren caught English vessels unloading cargo, and no less than five large English cogs were seized before they could escape. Two of these ships, Cog Edward and Cog Christopher, were royal vessels, personal possessions of the English king, and their capture was a blow to the royal pride. The French raiders, whose numbers included some Italian and Spanish mercenaries, were particularly brutal to English crews. The hapless mariners were all executed without mercy.

The French then attacked Southampton on October 5, 1338. Several thousand raiders attacked the port from both land and sea. The terrible scenes that Portsmouth witnessed were repeated, and perhaps with even more fury. English merchants who had the misfortune of falling into raider hands were hanged, often just outside of their homes. The French carried off goods or simply destroyed them. As they departed, they razed the port to the ground.

Meanwhile, the first land campaigns against Philip had proved embarrassing fiascos. Edward and his allies marched through French, or French-allied, territory putting everything of value to the torch. In so doing, the English king hoped to draw Philip out and lure him into a decisive battle, but the French king refused to rise to the bait. A deeply frustrated Edward was forced to withdraw into friendly Flanders.

Yet again Edward suffered financial embarrassment, and he was forced to borrow from rapacious Italian bankers at high interest rates. The spendthrift king would later default on these loans, triggering a financial crash that sent ripples of woe up and down the Italian peninsula. But in the short term, Edward realized he needed to go back home and prepare for the next campaign.

The king owed money to the Flemings, too. Bribery was an accepted mode of diplomacy in those days, and the cash-strapped monarch needed to pay up, lest he lose his hard-won allies. Edward left the continent and returned home, staying in England from February 21, 1340, to June 22, 1340. But in exchange, the king had to leave his wife, Queen Philippa; his two sons; two earls; and other high-ranking hostages to ensure that he would return to Flanders.

England had no purpose-built navy, and one of Edward’s chief concerns during the war was the building of a fleet that could protect the realm, safeguard English trade in time of war, and transport English troops to the continent. But there was a major problem: Such a fleet would be ruinously expensive to maintain.

As it was, King Edward possessed only a handful of ships; at one point, he owned only three vessels. This small nucleus was augmented in time of war by drafting merchant vessels into temporary service, a practice known as “arresting.”

Arrested ships were not merely seized, however; they were taken only after a contract had been signed with their owners. The captain, or master, and the crew were also deemed to have been drafted to serve for the duration of the campaign or war. Under such arrangements, masters were entitled to six pence a day, while ordinary seaman received three pence.

Early in 1340, with Edward still making preparations in England, the allies were surprised by a French land offensive towards Cambrai in Hainault. It was decided that Edward would return to the continent, and, once his army was landed, would march on French-held Tournai. But that was easier said than done because there were numerous delays in mustering a fleet. Some ships had been siphoned off to join a wool convoy, and there were further problems because Edward’s Admiral Morley had arrested neutral ships in port that had no part in the war. As if that were not bad enough, Morley and his assistants were helping themselves to merchants’ goods, too busy with clandestine plunder to mind what was going on.

Many ships were also avoiding service altogether, because they knew the contracts that they signed with royal agents simply might be not worth the paper they were written on. The English king, like most medieval rulers, was a poor paymaster, and there was no guarantee they would ever see money they were contractually promised. Those feelings also were likely shared by many, if not all, shipbuilders ordered to either build a ship from scratch or covert a cog to a warship.

Edward originally wanted to sail in mid-March, but delay after delay kept postponing his departure date. The King’s Council decided on June 4, 1340, that the naval expedition would go with the naval vessels it already had, which amounted to about 40 ships. It was possible that additional ships might join the fleet later. But there were French spies in England, and they quickly transmitted this information back to King Philip and French authorities.

With such intelligence in hand, the French made a bold move. They mobilized quickly, assembling a large fleet that they called the Grand Army of the Sea, and set sail for Sluys, which was situated at the Zwin estuary. The estuary was one of Europe’s great harbors and was Edward’s entryway to the continent. Once he landed at Sluys, Edward could travel a few miles up the Zwin to his ally, the great mercantile city of Bruges, and then besiege Tournai.

The French intended to block the entry port, and, if fortune favored them, do even more. Philip hoped that French naval forces would catch the English out in the open waters of the English Channel and utterly destroy them. No holds would be barred; indeed, there was even hope that Edward III himself would be killed in the action. In this Gallic dream scenario, the English throne would then go to Edward’s young son, also named Edward and only nine years old. In the feudal age, having a minor as King of England would be potentially disastrous, creating a power vacuum the French could exploit to their advantage. If the French captured Edward, he could be held for a huge and economically crippling ransom.

The Grand Army of the Sea was indeed an impressive force of 171 ships, four galleys, and 25 barges. They were manned by 20,000 sailors, but curiously had only about 500 crossbowmen and 150 men-at-arms aboard. Accounts maintain the Genoese and Norman French sailors were tough, inured to hardship, and used to armed conflict.

The galleys, if used properly, might tip the scale in favor of the French, especially since they were manned by professionals from Genoa. It took time and training to produce seasoned galley oarsmen, a luxury that other nations like the English simply did not have. But the Genoese galleys in French service were much reduced in number. The English had succeeded in destroying 18 galleys in the harbor at Boulogne during a raid, and there was also a separate pay dispute with King Philip VI

The French king imprisoned 15 Genoese, but the disciplinary action refused to cow them. Most of the galley mercenaries went home to Italy, and it was said that English bribes helped keep them there. The remainder was a skeletal force of possibly as many as six galleys commanded by Pietro Barbanero. Barbanero was a tough old sea dog who was said to have dabbled in piracy.

The English had an efficient spy network, and King Edward received word that the French Grand Army of the Sea was now in full possession of the Sluys estuary. This was troubling, because the door to the continent and his ally Bruges was now slammed shut. But Edward was also prescient enough to be worried about the growing threat of French sea power. The French armada was huge; its very size seemed to indicate that Philip was poised to invade England.

The matter was urgent enough to summon Edward’s top advisors, including his chancellor, Robert Stratford, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Edward wanted to sail as soon as possible, even though only 40 ships had been mustered. The archbishop felt this was madness, a suicide mission, and plainly told the king so. Tempers started to flair, and finally Stratford rose from the table and stormed out. He immediately tended his resignation as chancellor, declaring he was too old to be arguing with such a robust and forceful monarch.

Edward next turned to his admiral, Sir Robert Morley, and Morley’s assistant Jack Crabbe. Crabbe was a colorful character whose past included episodes of outright piracy. He was useful to the English because he knew the English Channel and North Sea waters intimately. Both Morley and Crabbe agreed with Stratford and insisted that crossing over to Flanders would be a bad move that would lead to disaster.

Once again Edward vehemently disagreed, and the conference deteriorated into a shouting match between the two men and their king. Edward, boiling with rage, accused them of either conspiring with the archbishop, or of being cowards. Morley and Crabbe fired back, saying they would lead the expedition immediately as ordered, even though it was going to lead to certain death.

Edward soon calmed down, especially when it was pointed out that the winds were unfavorable at for a channel crossing. He could be gracious, and he was big enough to recognize when he lacked knowledge and to apologize when he was wrong. The king attempted to make amends with Archbishop Stratford, but the prelate refused to return to his former position as chancellor.

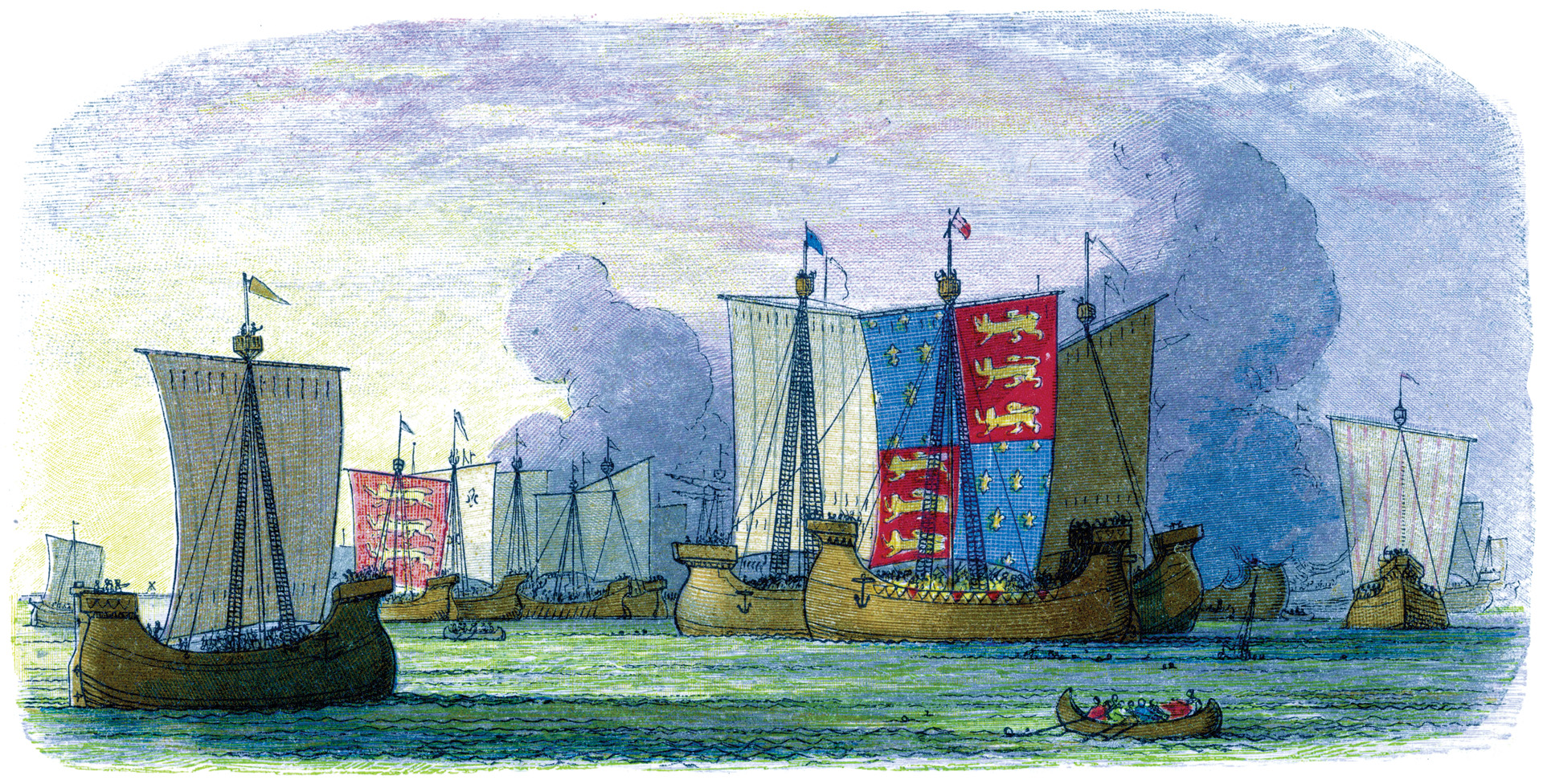

Edward eventually pulled off a minor miracle and was able to set sail on June 22 with a respectable force of approximately 200 ships. The fleet carried 10 earls, 50 bannerets (knights who led their own companies of men), 600 knights, and 12,000 mariners. But most important of all, the English ships carried 7,000 archers, whose longbows were on the verge of making history.

As soon as the English fleet arrived off the Flemish coast, Edward ordered a halt and ordered all of the vessels to anchor for the night. The king used the time to send Reginald Cobham, Sir John Chandos, and Stephen Lambkin to scout and reconnoiter the French fleet. Shielded by the cloak of darkness, they were able to get close without detection and gleaned valuable information about the foe.

The French were thrown into considerable consternation at the sight of such an enormous English fleet, for they thought that Edward possessed far fewer ships. The two French admirals, Hugh Quieret and Nicholas Bechuhet, decided to adopt a strictly defensive posture, a posture of such strength the English would find it impregnable.

The Italian mercenary Barbanero urged that they reconsider these arrangements, saying it would be better if the French fleet put out to sea. “My Lords, if you believe me, the whole [French] fleet ought to be moved onto the open sea,” said Barbanero, “for if you remain here, the English who have the wind, the sun, and the flow of the water with them in so much that they will confine you because you will be able to help your ships only minimally.”

The two admirals had no experience in sea commands. Indeed, one of them was a tax official in his previous career. Nevertheless, they looked down on the Italian as a low-born foreigner whom they tolerated because they had no other choice. Behuchet would have none of it, dismissing the advice with contempt. “He is a coward who retreats from here and does not stand ready for the onset of battle,” the Frenchman flatly declared.

The physical features of the estuary seemed to favor the decision to stay put. The Zwin estuary, which is today silted up beyond recognition, was in 1340 a body of shallow water about three miles wide, bounded on the northeastern side by Cadzand Island and the west by a long dike. The estuary narrowed considerably but continued another ten miles to the great city of Bruges. The city of Sluys was an entry port to Bruges and had been given its name due to the locks, or sluices, that regulated the waters of the ship canal.

The French ships arrayed themselves in three lines that blocked the three-mile-wide main channel. Each vessel was chained to its neighbors, side by side, with the prows facing outward and towards the enemy’s presumed approach path. The ships already had forecastles and aftcastles, but these were augmented by bretasches, which were small wooden balconies with machicolations (“murder holes”). The overall effect was to fuse all the ships into a kind of a massive floating castle.

The first French line was the strongest, consisting of no less than 19 of the largest warships, headed by the Cog Christopher. This was meant to both irritate and taunt the English, because Christopher was once the pride of King Edward’s navy. Captured with four other English vessels in 1338, she was a painful reminder of the raids the island nation had so recently endured.

Edward was no seaman, but he recognized the value of listening to people whose expertise in such matters was superior to his own. The English were ready for battle in the early morning but paused for a few hours, waiting for the tide to turn. When the tide finally did change at about 10:40 am, Edward gave the orders for the fleet to set sail.

The French had girded themselves for battle and watched in grim anticipation as the great mass of English ships, sails billowing in the wind, drew ever nearer. But the English mariners started tacking, heaving on ropes to change the angle of the yards, until the whole fleet seemed to be turning away from the Flemish coast. It looked as if they were retreating, turning tail, and the spectacle aroused a kind of hunting instinct among some of the French.

The crafty English were escaping, or seemed to be; therefore, some of the French ship masters cut the chains that bound them to their neighbors and went forward to give chase. But the English were not retreating, merely circling around to get a better position with the wind at their backs. There were now gaps in the first line of the French “ship wall.” The English moved quickly to exploit the gaps to the fullest extent possible.

The English got into a formation that echoed land battles to come. Each ship that was full of men-at-arms would be flanked by two ships packed with longbowmen. Men on both sides felt a sense of fear, excitement, and adrenaline coursing through their bodies. As the English approached the French, the sounds of music could be heard. It was unmistakable and could be heard even by men whose ears were covered by mail coif or a helmet.

The French were playing a variety of drums, trumpets, and other instruments familiar to the minstrels of the period. The concert was designed to show defiance to the enemy and to muster courage in the breast of everyone aboard the Grand Army of the Sea. Not to be outdone, the English responded with their own tunes, a kind of musical duel that foreshadowed the bloodier competition to come.

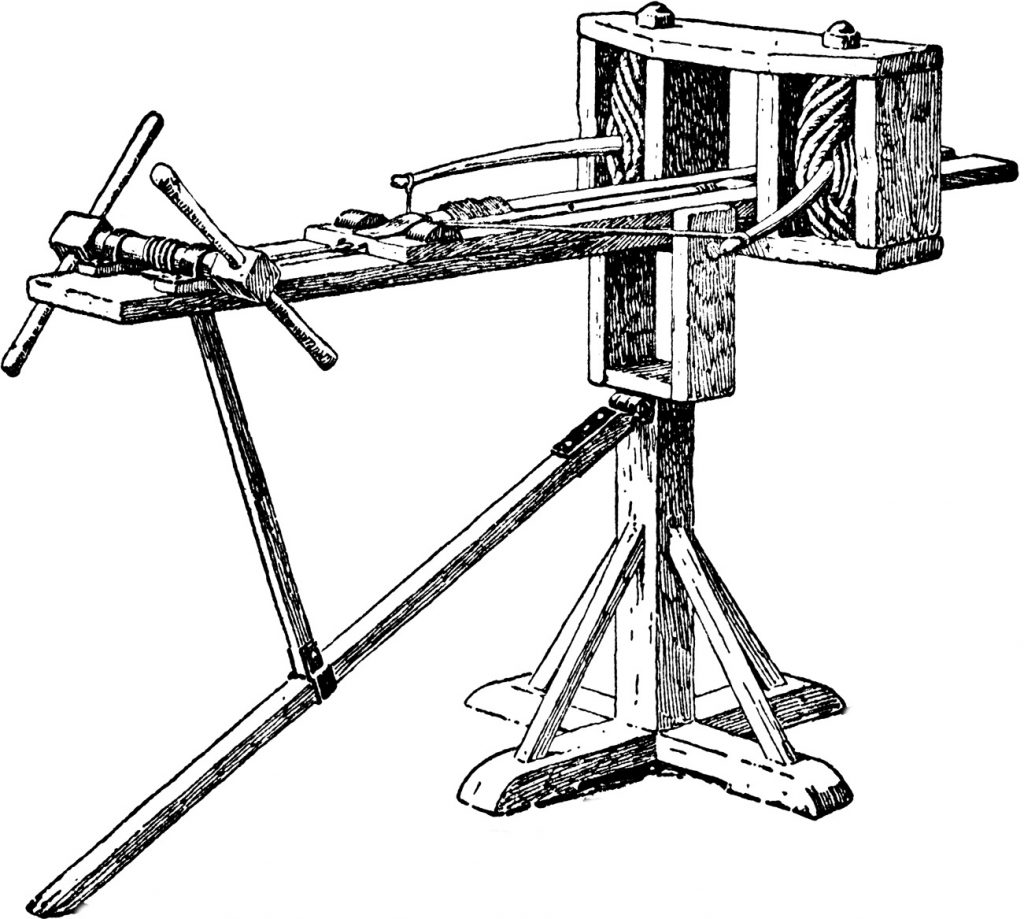

The battle opened with volleys of stone thrown by French shipboard ballistas (similar to giant crossbows), launched as soon as the rival ships were within range. They were answered, and even matched, by English springalds (similar to ballistas) throwing stones and burning pitch. Sir Robert Morley’s cog was the first to reach the French ships, and soon a bloody and protracted melee was in progress.

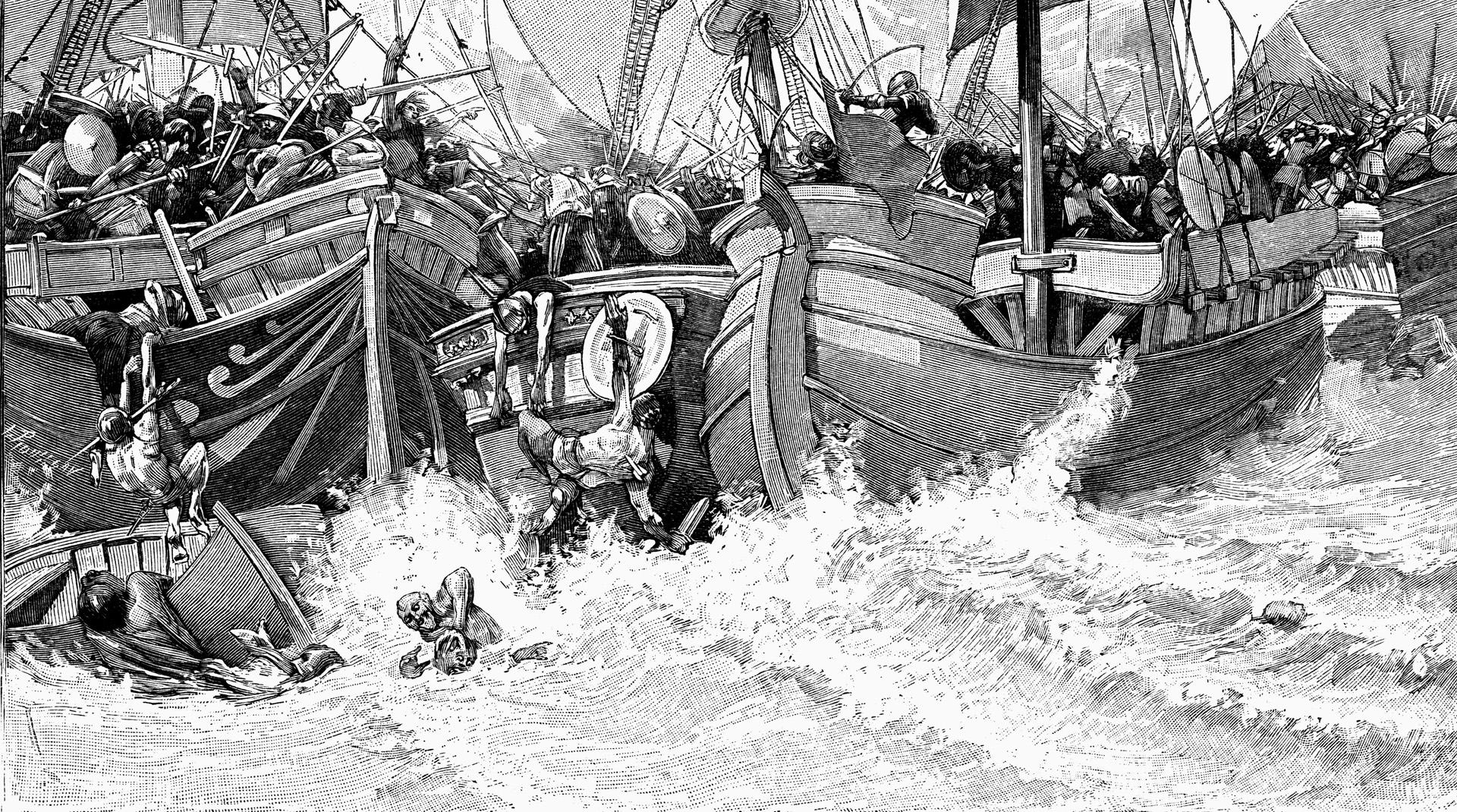

One English galley was a little bit too swift, and it raced so far ahead it found itself alone and in the midst of enemies. Pelted with rocks and peppered by crossbow bolts, the crew was slaughtered. But in general, Edward’s tactics were working well. The longbowmen sent showers of arrows into the French ships. “Our archers and our arbalesters began to fire as densely as hail falls in winter, and our engineers hurled so steadily, that the French had not power to look or to hold up their heads,” stated The French Chronicle of London. Hundreds of lethal shafts rained down, suppressing French stones and crossbow bolts so effectively that all the French could do was seek shelter from the arrow storm and await the inevitable boarding.

The Genoese crossbowmen could only fire perhaps four bolts in a minute; in that same time, a trained longbowman could launch 10 arrows. Once the French fire was reduced, it was the job of the men-at-arms to board the enemy vessel to complete the job. Grappling hooks made sure the opposing ship could not escape. French decks became the scenes of bloody melees, brutal and intimate, where men hacked, stabbed, and grappled with each other at close quarters with savage abandon.

King Edward himself was an active participant, risking his life like an ordinary knight or man-at-arms. Men-at-arms wielding swords, axes, and polearms struck armor or other weapons, producing a terrible ringing cacophony like a thousand blacksmith forges, the din punctuated by shouts of rage and screams of wounded men. The king was struck with a crossbow bolt in the thigh. It proved to be a serious wound that dyed his lower leg and boot with blood.

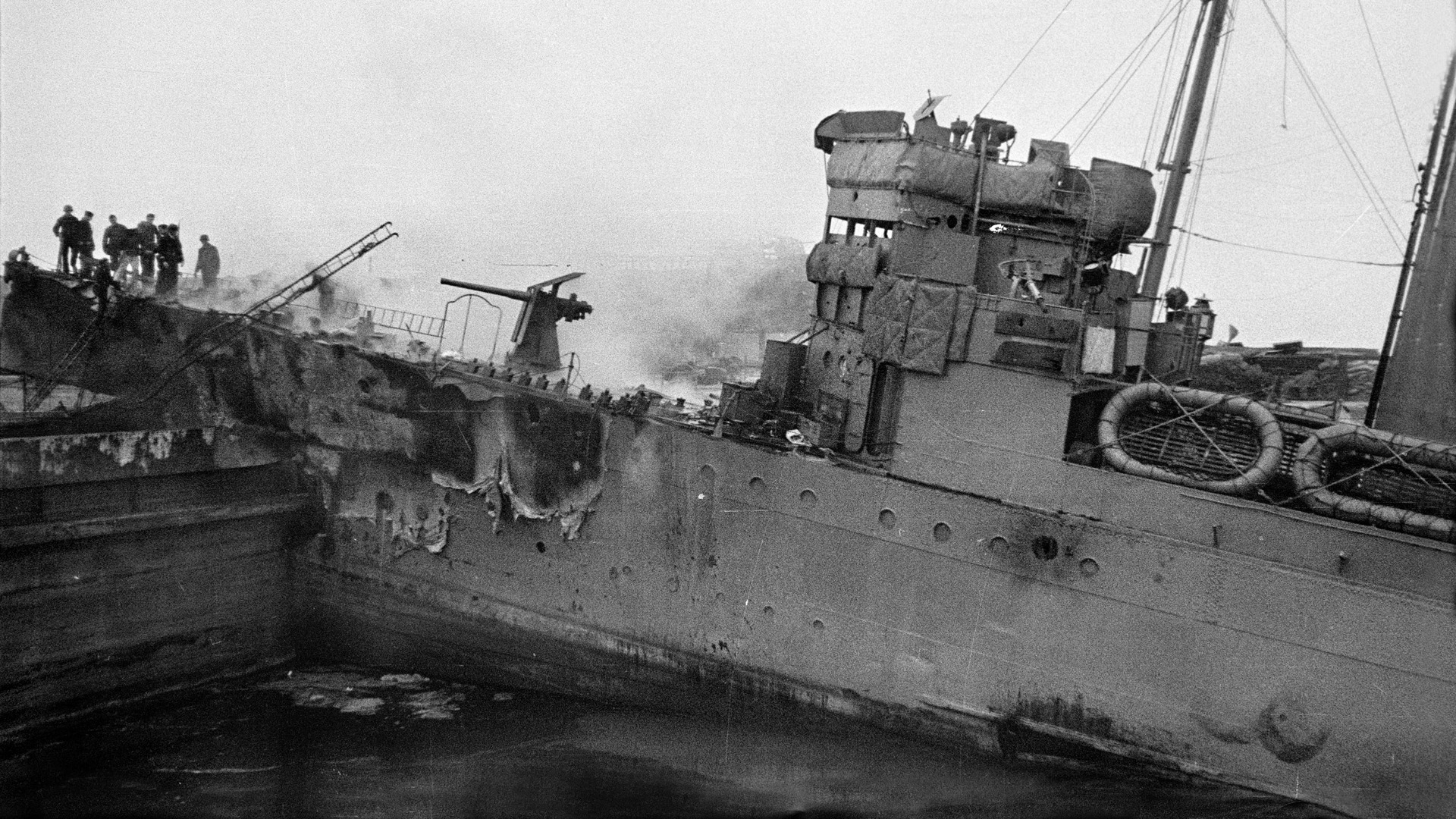

The first line of French ships were defeated and taken, with the Christopher triumphantly back in English hands once again. The English slaughtered the French crews to the last man and flung their corpses overboard. Indeed, so many corpses floated in the estuary it was said that the waters literally turned red with blood. Medieval chroniclers, usually far from squeamish, describe the fight as “dreadful” and “not for the faint heart.”

The fight in some cases lasted throughout the night, light being provided by burning ships. The great French vessel La Seint James became entangled with an English ship owned by the Prior of Christchurch, but its crew fought with stubborn valor. The next morning the English had succeeded in taking the ship, and in the process of mopping up, they flung 400 French corpses into the sea.

The second and third lines of French ships seem to have collectively lost heart when they saw the first line so decisively defeated. The fighting went on, but more and more French and Norman crews abandoned ship in a desperate attempt to save their lives. Many drowned because of the weight of their mail. Perhaps some preferred downing to the pain of stabbing or dismemberment, because in this era many sailors did not know how to swim. Vengeful Flemings, who had been watching the battle as spectators, killed those Frenchmen who tried to swim to shore.

The French admirals paid for their folly with their lives. Hugh Quieret was captured badly wounded; the English knights wasted no time in doing away with him. They cut off his head and flung it overboard. Behuchet was taken alive and brought before King Edward aboard the flagship Cog Thomas. The Frenchman probably thought he was going to be ransomed, as was customary with high-status prisoners, but he was wrong. Edward was in no mood to be generous, for he vividly recalled the slaughter and destruction wrought by Gallic raids on the English coast. Edward ordered Behuchet hung, and his corpse was left to dangle from the yardarm of the king’s ship as a warning to others. Barbanero managed to extricate his galleys from the French lines when he saw all was lost, and approximately 17 other French ships escaped. The rest were captured or burned.

The casualty figures also reflected what a debacle Sluys was for French naval power. Medieval casualty numbers usually vary wildly, and Sluys is no exception. Modern conservative estimates list English losses at four knights and upwards of 600 other types of soldiers. French casualties were appalling and ran as high as 20,000. The Sluys estuary was crowded with dead bodies, and the tide washed corpses ashore for days thereafter. A contemporary English jest maintained that if the fish in the Sluys harbor could speak, it would be in French given that they had dined on so many French bodies.

Sluys gave England undisputed control of the English Channel for a time, and fears of a French invasion were at last laid to rest. From that point forward, English armies and supplies could reach the continent without fear of being intercepted en route. In the long term, Sluys yielded fewer results: Philip VI still had enormous resources, and in time, a new fleet with a new admiral, Robert de Houdetot, would once again threaten English shipping.

Sluys stands as one of the great battles of English history, a worthy companion to more modern British naval victories such as the epic sea battles of Trafalgar and Jutland. During medieval times, it began a cycle of English victories over the French that would unfold on the battlefields of Crecy, Poitiers, and Agincourt.