By Joshua Shepherd

After just one month of training, the men of the 27th New York Infantry nervously sensed they would be in the middle of a real fight within minutes. As a part of Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s Union Army of Northeastern Virginia, the regiment had splashed across the shallow waters of Bull Run on the morning of July 21, 1861. The New Yorkers were participating in a large-scale turning movement that, McDowell hoped, would finally bring the Confederate army to bay and put an end to the rebellion.

Soon after crossing the stream, the New Yorkers could hear the sound of a growing fight in the distance. They listened intently as the isolated pop of rifled musket fire that grew to a steady roar. The occasional dull boom of artillery signaled that what was developing out front was no minor skirmish.

After cresting Matthews Hill a mile south of Sudley Ford, the men realized that they were suddenly facing a real battle. Clouds of acrid white smoke rose from the valley below them, and Confederate artillery posted to their front was sending shells crashing toward the Union line. A jittery staff officer abruptly arrived with orders to the regiment’s commander, Colonel Henry Slocum. Excitedly pointing downhill, the officer ordered Slocum forward with brief orders. “You will find the enemy down there,” he said.

“Come on boys!” shouted Slocum, “Let us silence that battery—come strike for your country and your God!” As the New Yorkers started forward, they were targeted by Confederate guns and given a terrifying lesson on the horrors of combat. Private William Westervelt described the first harrowing moments of enemy fire. “Here I saw the first man killed, who was marching just in front of me was struck with grape shot over the left eye,” recalled Westervelt. “He gave an unearthly screech and leaping into the air, came down on his hands and knees, and straightened out dead.”

The bloody clash that would come to the rolling fields and woodlots of what would be known afterwards as First Bull Run in the North and First Manassas in the South would be a painfully rude awakening for a divided nation gripped by war hysteria. Subsequent to the Confederate seizure of Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, in April 1861, the American people were inexorably headed for an internecine war that had been feared for decades.

President Abraham Lincoln issued a call on April 15 for 75,000 volunteers to subdue the South. Although violent skirmishes broke out in remote and outlying areas, such as Missouri and northwestern Virginia, it became readily apparent that a major clash would take place in Northern Virginia. Strategically situated between Washington, D.C. and the new Confederate capital at Richmond, VA, the region seemed to offer the tantalizing prospect of a quick end to the war.

By making an overwhelming move on Richmond, the Lincoln administration hoped to seize the Confederate capital and, in one bold move, frighten the errant Confederates into submission. With any luck, the secessionists would be brought to their senses by such a show of force and the Confederate lion would be put down by the end of the summer.

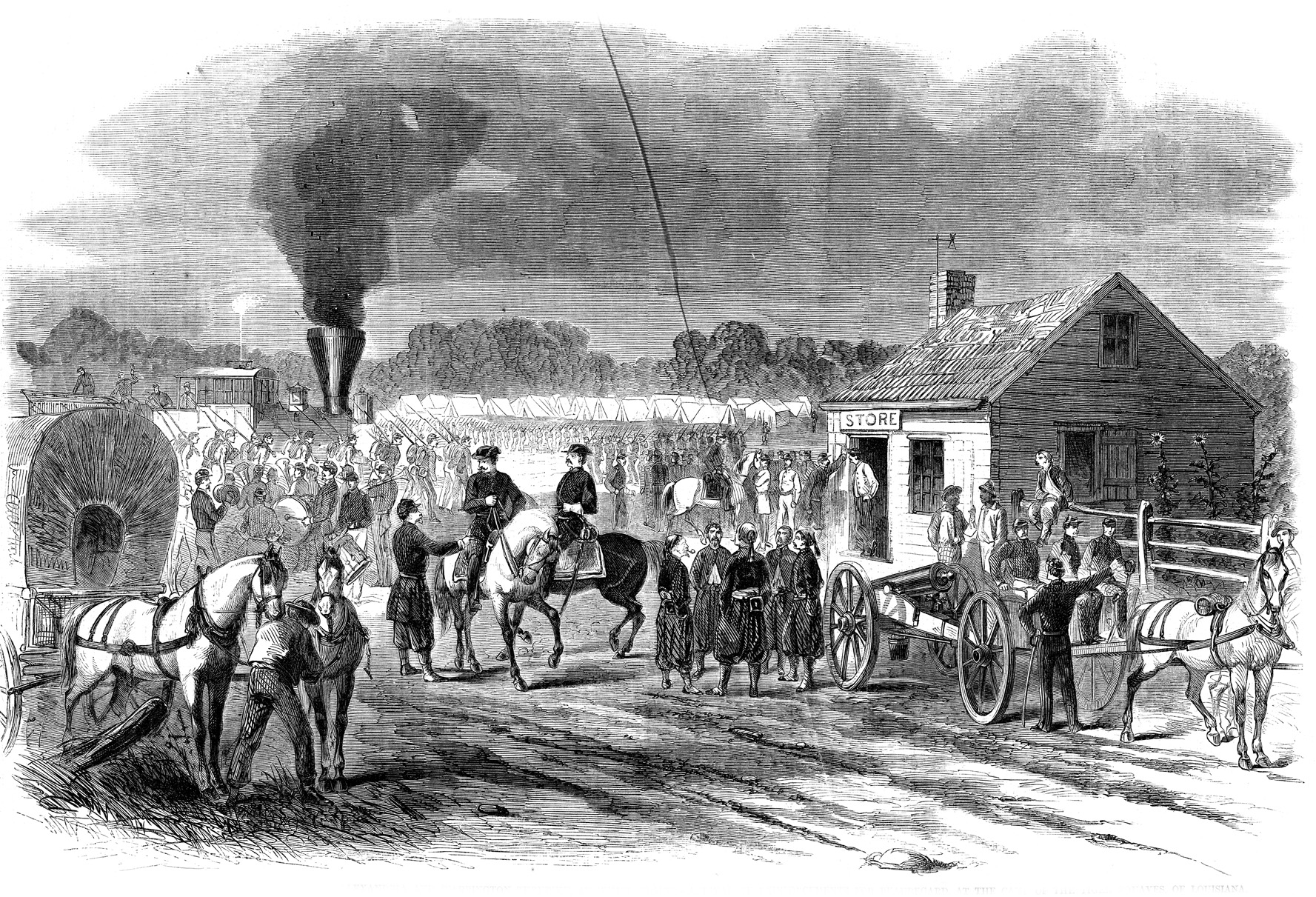

McDowell’s army was bulging with volunteer regiments whose men were bursting with patriotic fervor. They were well-armed and supplied, but totally inexperienced. Washington had become an armed camp, teeming with raw recruits. Although the officer corps contained a good number of seasoned career men, few of them had experience in commanding more than a company in battle. When it came to wielding brigades and regiments, even high-ranking officers would be venturing into uncharted waters.

Lincoln entrusted McDowell with overall command of the Federal advance on Richmond. A career soldier with political connections, McDowell did not possess the unbounded enthusiasm so rampant throughout the North. Although he commanded the largest army the nation had ever fielded, he was acutely aware that his raw recruits were not up to the task of actively taking the field. For this reason, he pleaded for more time to train his green troops. But political considerations, paired with a Northern press that ceaselessly clamored for an advance, ensured that the troops would go on the offensive as soon as possible, regardless of whether they were ready.

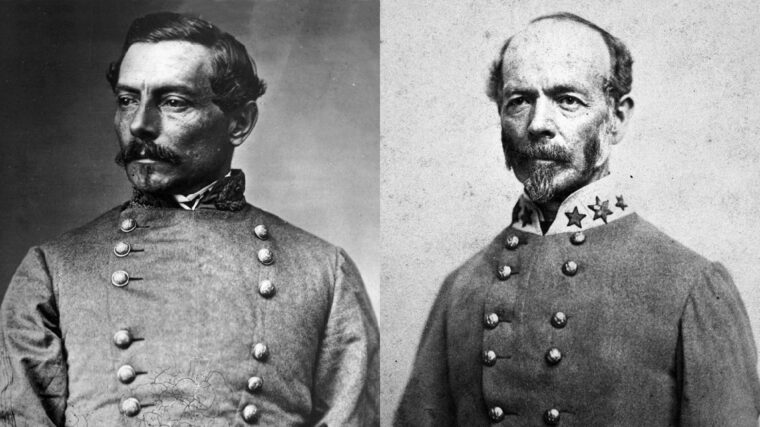

McDowell’s counterpart was equally anxious. Confederate forces in Northern Virginia were under the command of Brig. Gen. Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard, a flashy Louisiana Creole and Mexican War veteran. He was a hero in the South for directing the capture of Fort Sumter. Beauregard concentrated his forces in the vicinity of Manassas Junction, a crucial rail hub where the Manassas Gap Railroad from the Shenandoah Valley joined the Orange & Alexandria Railroad. But with just 22,000 men under his immediate command, Beauregard was badly outmatched.

A solution to the Confederate manpower shortage was close at hand, but it came with a catch. Confederate Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston commanded 12,000 Confederates in the lower Shenandoah Valley. Johnston was opposed by 18,000 Union troops led by Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson’s Union Army of the Shenandoah. Washington had instructed Patterson to maintain pressure on Johnston to prevent him from reinforcing Beauregard. Patterson would fail miserably in that task.

McDowell put his army in motion on July 16. Northern recruits unaccustomed to the suffocating heat of the Virginia summer suffered badly on the march. To his credit, McDowell scorned a frontal attack on Confederate defenses, which guarded the south bank of a narrow stream with steep banks known to the locals as Bull Run.

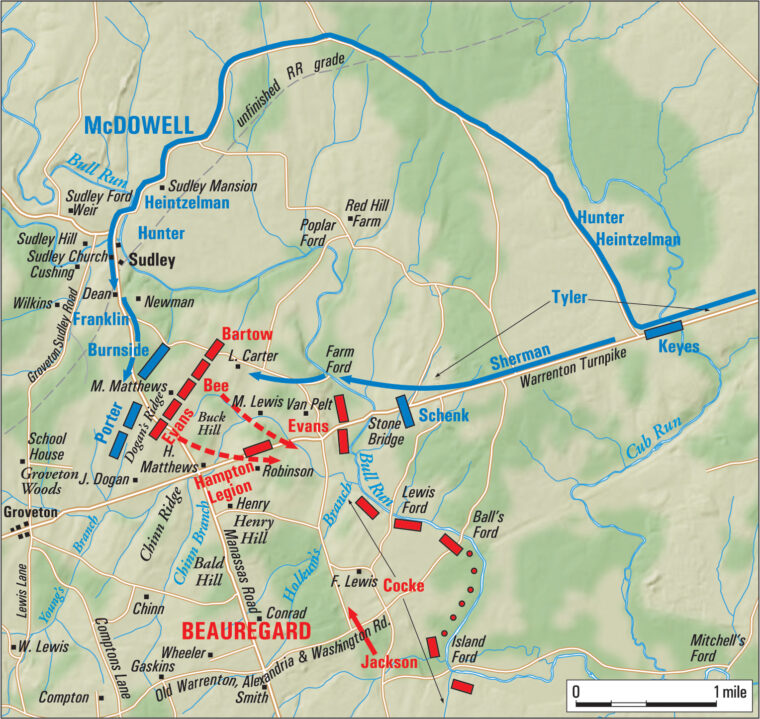

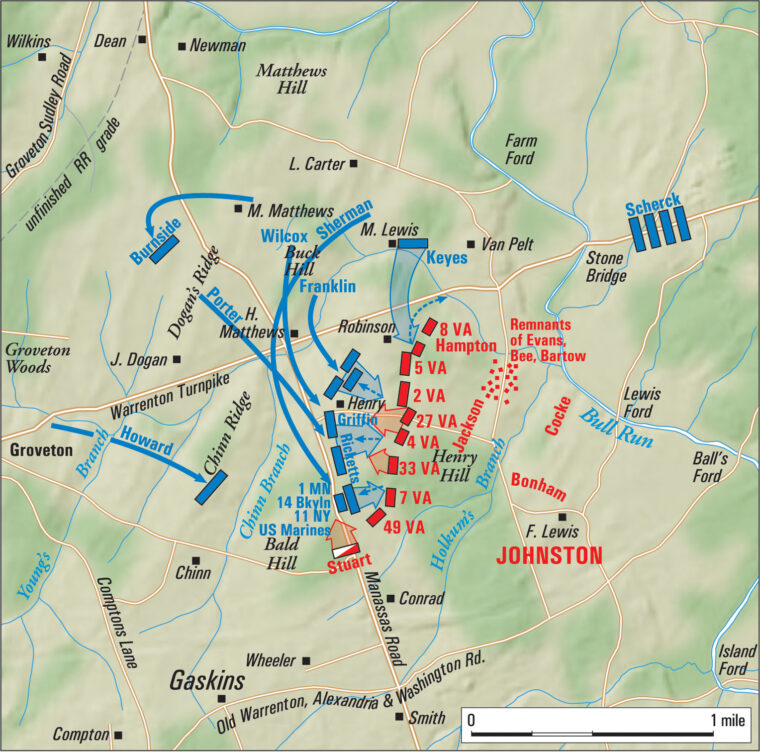

Beauregard deployed his army on a six-mile front behind the stream in order to guard its many fords, as well as a masonry bridge aptly named Stone Bridge on the northern end of his line. Rather than attempt a forced crossing of the heavily defended fords and the Stone Bridge, McDowell decided to try to fix the Confederates in place with diversionary attacks in order that a large portion of his forces might work around Beauregard’s right flank and cut off the Confederate Army’s retreat toward Richmond.

The plan to turn the Confederate right flank fell apart on July 18. After closer inspection of the ground, McDowell became convinced that a move around the Confederate right, which occupied rugged ground, was too risky. That same day, the Union Army’s energetic commander of its First Division, Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler, tangled with the Confederates defending Blackburn’s Ford. The fighting degenerated to a pointless fiasco.

By all appearances, the Confederate center and right was strongly defended. Realizing this, McDowell decided to send a significant portion of his army across an undefended upper ford of Bull Run located at Sudley Springs. Studying his maps, he devised a bold plan. While Tyler’s Division, advancing along the Warrenton Turnpike, would make a demonstration against the Stone Bridge and occupy the Confederates’ attention, two other divisions, led by brigadiers David Hunter and Samuel Heintzelman, who commanded the Union Army’s second and third divisions, respectively, would make a circuitous march to the north and west, cross Bull Run at Sudley Ford, and fall on the Confederate’s weakly defended left.

It was an excellent plan, but McDowell would eventually have to deal with the Confederate defenders of Bull Run. Oddly enough, Beauregard had developed a nearly identical plan, but in reverse, for the morning of July 21. Beauregard hoped to fix McDowell in place while he sent the bulk of his brigades in a crushing attack on the Federal left flank.

The Confederates also had a devastating surprise in waiting. Beginning on July 19, General Joseph Johnston’s Confederate Army of the Shenandoah began arriving at Manassas Junction after departing Winchester, Va. Johnston succeeded in bluffing Patterson into thinking that the Confederates were staying in the Lower Shenandoah Valley. Much of Johnston’s force was swiftly moved by rail; though, the movement of Johnston’s army was not completed until the morning of July 21. The arrival of Johnston’s 12,000 troops gave Beauregard’s army a momentum-shifting influx of manpower.

McDowell’s troops began their flank movement at 2:30 a.m. on July 21, but the march was bedeviled by bad luck from the outset. Tyler’s Division, which had just three miles to march, proceeded at an excruciatingly slow pace. His forces created a bottleneck on Warrenton Turnpike, thus denying Hunter’s and Heintzelman’s divisions access to the quickest route to Sudley Ford; as a result, their troops had to march more than 10 miles to reach the ford. Of particular nuisance was the decrepit wooden bridge over Cub Run. A narrow span that turned into an agonizing bottleneck, the bridge ensured that the troops of Hunter and Heintzelman did not really get moving until the sun was nearly up. It was hardly an auspicious beginning to the day’s movement.

By 6:00 a.m. Tyler was in position astride the Warrenton Turnpike just north of Bull Run. The honor of opening the first major battle of the Civil War fell to Lieutenant Peter Hains of the 2nd U.S. Artillery. He fired the first shot of the battle opening up on the Confederates with an immense 30-pounder Parrott rifle that had been muscled to the battlefield. Hains broke the morning silence by firing several rounds toward Confederate positions west of Bull Run. A Union battery of field artillery soon opened up as well.

In keeping with his orders to mount a diversion, Tyler ordered Brig. Gen. Robert Schenck’s Brigade to make a demonstration toward the bridge. They were greeted by well-concealed Confederate skirmishers, and the crackle of musketry indicated that a real fight was in the offing.

For Johnston, who technically was the senior Confederate officer on the field, the clash of musketry at the Stone Bridge could not be ignored. Anxious to bolster the weak Confederate left that was clearly under the threat of attack, Johnston ordered three of his brigades, those of Brig. Gen. Bernard Bee, Colonel Francis Bartow, and Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson, as well as the South

Carolinians of the Hampton Legion, to move toward that flank. Bee, an old Army man, was disgusted. Convinced that all the real fighting would unfold on the right, the dejected general slumped off to his new position, which, he was convinced, would be a quiet one.

Despite the skirmishing that had erupted at the Stone Bridge, Beauregard’s grand plan for striking the federal left was scheduled to proceed. Brig. Gen. James Longstreet’s Brigade crossed Blackburn’s Ford, while D.R. Jones’ troops splashed across McClean’s Ford. Both brigades formed up for an assault, and waited for the fight to open on the far right, where Brig. Gen. Richard Ewell’s Brigade had orders to cross Bull Run and attack the Federal flank.

But an inexplicable hush fell over the field. The courier carrying Ewell’s orders disappeared. Ewell, who was growing increasingly impatient, sat tight awaiting his orders to advance. It was a complete collapse of Beauregard’s plan, but as events would show one of the most fortuitous staff failures of the Civil War.

The Confederate brigade that guarded the Stone Bridge was subjected to constant skirmishing at 8:00 a.m., but was not hard pressed. Colonel Nathan “Shanks” Evans, who commanded a demi-brigade composed of two infantry regiments, a cavalry regiment, and an artillery battery, was increasingly convinced that the Federals were simply demonstrating against the bridge.

On the opposite flank, a young Confederate signal officer would make an unexpected and historic discovery. Captain Edward Porter Alexander, situated at a signal station on the Confederate right, inadvertently caught a glimpse of a bright flash in the fields off the Confederate left flank. Taking a closer look, Alexander could clearly make out a mass of gleaming Federal bayonets in the morning sun. He immediately sent a terse signal to Evans. “Look out for your left, you are turned,” warned Alexander.

Evans acted quickly on his own initiative. Leaving just four infantry companies to defend the Stone Bridge, he marched the rest of his brigade to the north in an attempt to intercept the Federal forces headed his way. Evans marched his troops onto the southern slope of Matthews Hill.

Evans positioned his troops in a curious manner. Rather than occupy the commanding summit of the hill, he deployed his men on lower ground about 150 yards below the crest on the reverse slope. Although his men would initially be concealed from enemy view, they would be at a decided disadvantage when the fighting started.

Soon after the Confederates reached Matthews Hill, a prominent height east of the Manassas-Sudley Road, Union skirmishers worked their way over the crest. A Confederate volley sent them reeling. Colonel John Slocum’s 2nd Rhode Island Infantry advanced to the top of the hill and opened fire on Evans’ Confederates. It was a jarring experience for green troops on both sides. “[My] first sensation was one of astonishment at the peculiar whir of the bullets,” recalled Elisha Hunt Rhodes of the 2nd Rhode Island.

Although Evans’ men initially enjoyed a bit of cover, the Federal troops suffered badly along the crest of the hill. Hunter, the commander of the Union Second Division, was shot in the neck. In just a matter of minutes the field was covered with dead and dying men whose first taste of combat was tragically brief.

Reinforcements were slow in making it to the field. Colonel Ambrose Burnside eventually managed to get his 1st Rhode Island Infantry into the fight, and placed them to the left of the 2nd Rhode Island. Evans’ Confederates had no intention of simply trading volleys with the enemy. Major Roberdeau Wheat, a barrel-chested veteran and soldier of fortune, led the soldiers of his 1st Louisiana Battalion in a mad charge up Matthews Hill. The Louisiana Tigers, as they were called, nearly made it to the Federal line when they were stopped by heavy fire from the Rhode Islanders.

Realizing that the Federals would inevitably overpower his lone brigade, Evans dashed for the rear to locate help. Evans sought out Gen. Bee, and pleaded with him for immediate support. Although he initially disinclined to lead his men into what was clearly a disadvantageous position, Bee eventually relented when he realized what was at stake.

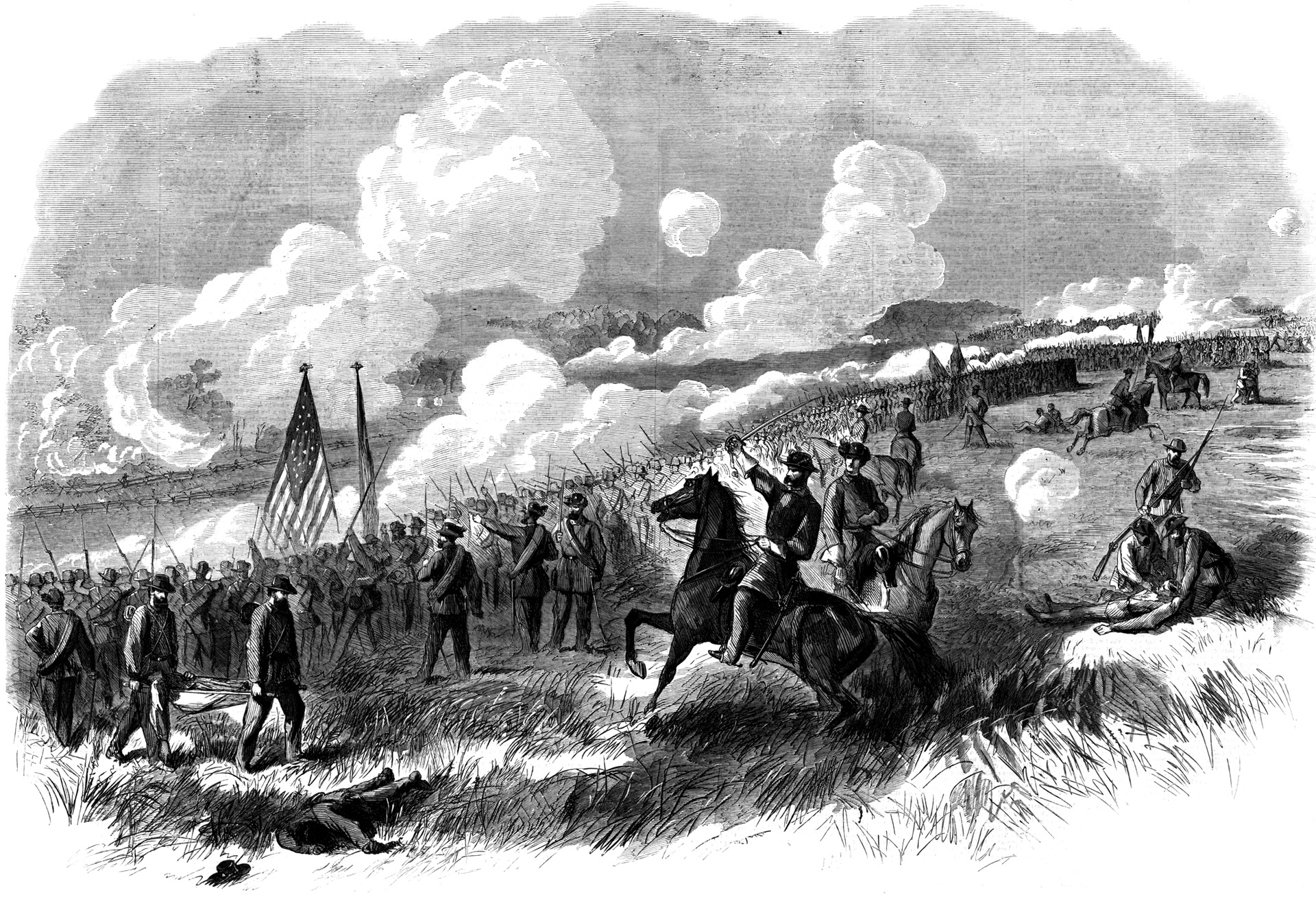

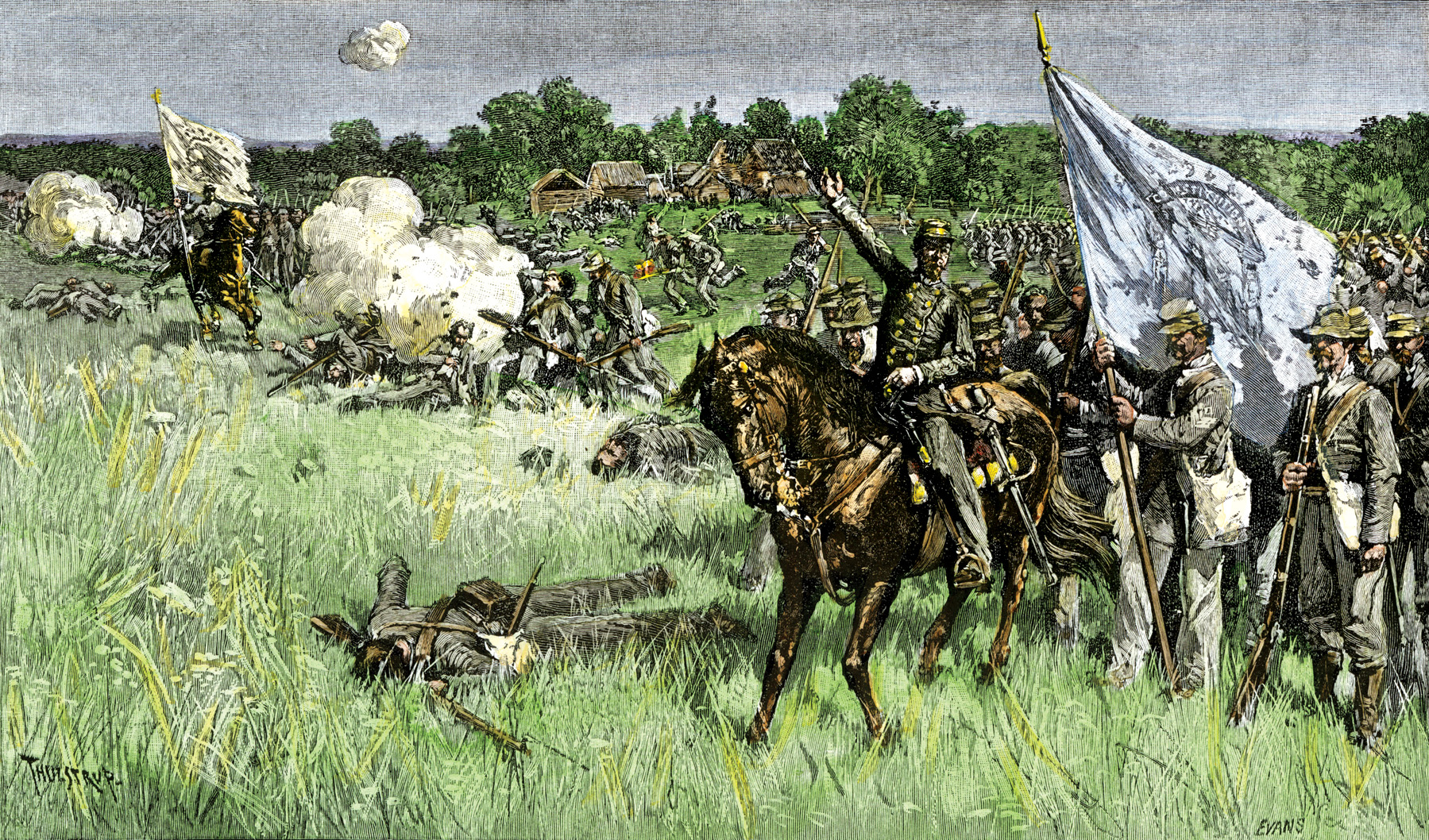

Both sides funneled troops into the fight, which degenerated into a slugfest. Bee not only brought up his own brigade, but also brought with it Bartow’s Brigade. The Confederate reinforcements tied into Evans’ right flank, extending the Confederate line to the east. In firm possession of the top of the hill, Burnside brought up fresh reinforcements. Although his troops were taking heavy casualties of their own, they succeeded in pouring a murderous fire down the slope of the hill. They soon began to overpower the Confederates.

Green troops on both sides fought with surprising tenacity. Colonel Andrew Porter’s Brigade moved up on Burnside’s right, but it was the sudden arrival of Tyler’s oversized division, which was composed of four brigades, that ultimately spelled disaster for the Confederates on Matthews Hill. Tyler’s troops had brushed aside the small force of Confederates defending the Stone Bridge. After crossing Bull Run, the vanguard of Tyler’s Division angled toward the Confederate right flank on Matthews Hill.

With both of its flanks under pressure, the Confederate line began to buckle. On the left, Colonel Wheat, in the thick of the fighting, went down with a seemingly mortal wound to his chest. Although he would survive the battle, his troops joined with other battered Confederate units in a hurried retreat south. They fell back across the Warrenton Turnpike and ascended another commanding height known as Henry Hill. Confident that he had whipped the Confederates, McDowell shouted “Victory! Victory!” as he rode along the Union line.

But the Union commander’s assessment of the situation was premature. Far from abandoning the battlefield, Johnston and Beauregard, both of whom had eventually realized that the bulk of McDowell’s army had stolen a march across the upper fords of Bull Run, were working feverishly to shore up defenses on their threatened left flank.

At that point in the battle, the brigades on the extreme left of the Confederate line needed to fight a delaying action until they could be reinforced and a new line of defense established atop Henry Hill. The unenviable task of slowing the Union advance fell to Colonel Wade Hampton’s undersized Hampton Legion. A wealthy planter and natural-born fighter, Hampton had raised the legion, which was composed of infantry, cavalry, and artillery. Its combined arms structure meant that its infantry force was a meager one.

Hampton deployed his 600 infantrymen on Warrenton Turnpike just east of its intersection with the Manassas-Sudley Road. The South Carolinians traded fire with the Connecticut and Maine troops of Brig. Gen. Erasmus Keyes Brigade of Tyler’s Division. Overpowered by Keyes’ bluecoats, Hampton’s graybacks fell back to a new position behind the Robinson House on the north end of Henry Hill.

Despite the success that he had experienced during the morning’s clash, McDowell was reluctant to press his luck. Rather than maintain pressure on the confused Confederate left, he opted to rein in his badly disordered troops and reorganize before resuming his advance. The pause gave Confederate reinforcements time to reach Henry Hill. When McDowell’s troops resumed their attack, they found the Confederates in a much stronger position.

Blocking McDowell’s path was a brigade of Virginia troops commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas Jonathan Jackson, who was a graduate of West Point and a veteran of the Mexican War. For the past decade he had taught natural philosophy and artillery tactics at the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, VA. A taciturn soul who possessed a warrior spirit, Jackson was in his element on the day of the battle.

As soon as Jackson heard the fight erupt on Matthews Hill, he moved his men on wooded trails toward the sound of battle. On the way, he encountered a discouraged Bee, moving toward the rear but keeping his battered command in good order. “General, they are driving us,” Bee said. “Sir, we will give them the bayonet,” Jackson replied.

Such resolve would be sorely needed in the coming fight. Jackson deployed his 2,600 Virginians on the east side of Henry Hill. Rather than deploy on the crest, though, he formed his men on the reverse slope just out of sight of Federal batteries that would soon begin unlimbering opposite his position. Jackson’s five regiments had 300 yards of open ground to their front in which to target advancing Union troops. To bolster Jackson’s position, Johnston and Beauregard rushed all available artillery to Jackson’s sector. Before the Union forces arrived atop Henry Hill, the Confederates had 16 smoothbore cannon deployed to support Jackson and Hampton.

The first Union assault on the Confederate position atop Henry Hill came at 1:00 p.m. when the 3rd Connecticut and 2nd Maine of Keyes’ Brigade arrived. The two regiments lunged at Jackson’s right flank. It was a golden opportunity to roll up the Confederate line, but confusion over uniforms would snarl the attack from the outset. Union troops held their fire as they came forward, convinced that the graybacks in their front were fellow Federals.

The Hampton Legion and the 5th Virginia of Jackson’s Brigade fronted northwest to receive the attack. The Confederates unleashed a crashing volley into the New Englanders that threw their ranks into confusion. Keyes’ men regrouped and advanced anew. Their second assault drove the Confederates off the grounds of the Robinson House.

The 5th Virginia was far from finished, though. They poured sheets of musketry into Keyes’ ranks. Keyes withdrew his troops in the belief that unsupported they faced certain annihilation. He marched them back towards the Stone Bridge where they sat out the remainder of the battle.

In the wake of Keyes’ reversal, McDowell decided on a puzzling course of action. Rather than launch his considerable force of infantry to defeat Jackson, the general ordered two artillery batteries from the regular army, which were commanded by captains Charles Griffin and James Ricketts, to deploy on Henry Hill. Griffin was dumbfounded. After making repeated protests that the batteries were not up to the task of single-handedly facing off against the Confederate line, Griffin complied with the unusual orders.

The cannoneers thundered up the ridge line under heavy fire, wheeling into battery on either side of the Henry farmhouse. Griffin went into action on the left and Ricketts to his right. They unlimbered, initially without infantry support, just 350 yards from the Confederates.

Confederate sharpshooters concealed around the Henry house peppered the artillerymen with a galling fire. A frustrated Ricketts ordered his guns turned, sending shells crashing through the walls of the clapboard farmhouse where 85-year-old Judith Henry lay huddled in bed. Struck by artillery fire during the barrage, she died later that day amid the wrecked remains of her home.

While Griffin and Ricketts took a pounding from their Confederate counterparts, Union infantry came up in support. The 38th New York formed up on the left. The right of the Henry house was occupied by the 1st Minnesota and the 11th New York. The latter regiment was known as the Fire Zouaves because it had been recruited from the ranks of New York City firemen. Well-directed Confederate artillery fire swept the open ground atop Henry Hill, playing havoc on Union troops facing their first battle.

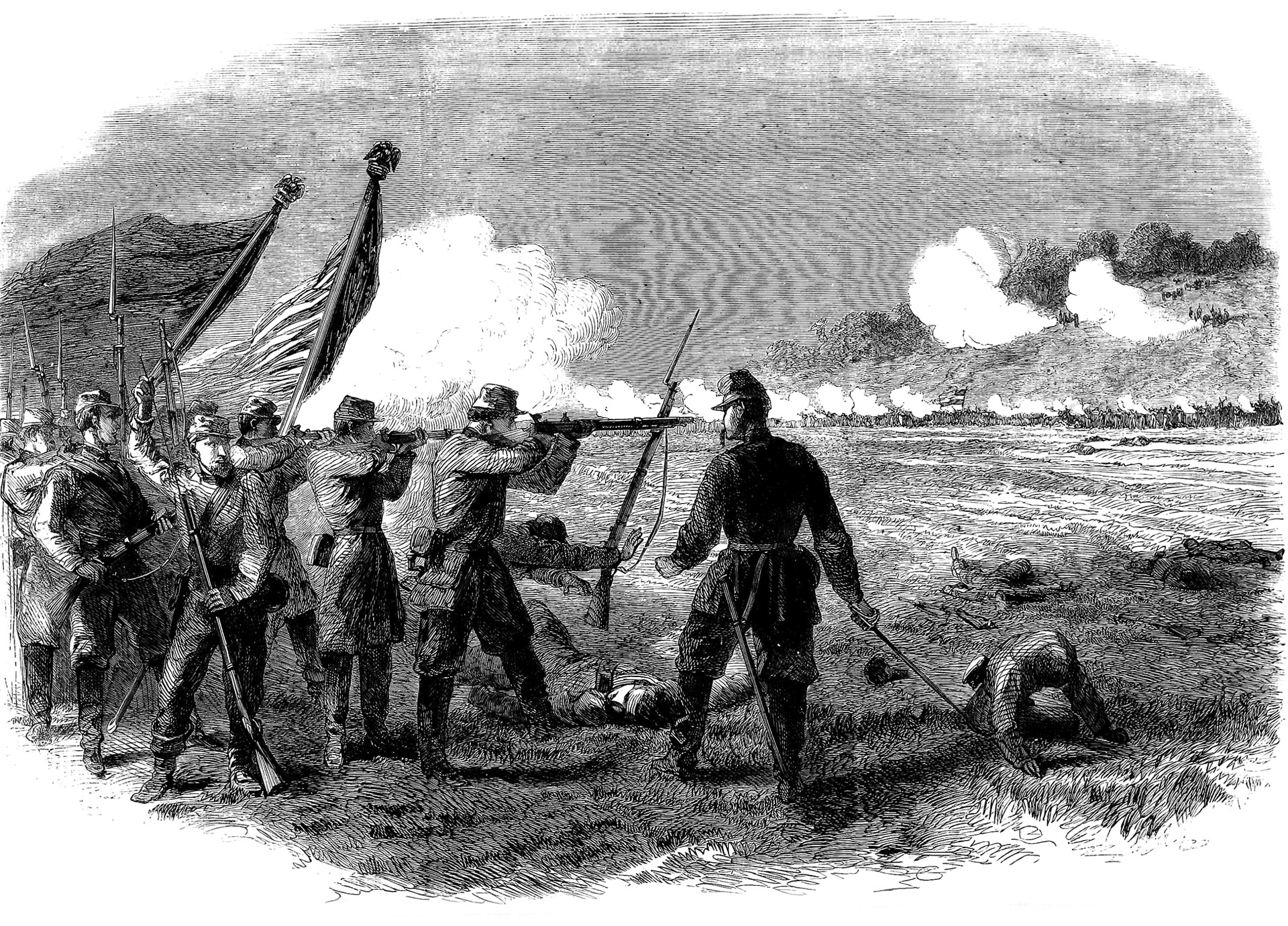

The Federal infantry swept forward at 3:00 p.m. Just across the hill, the Confederates steeled themselves for a toe-to-toe fight. Colonel Arthur Cummings of the 33rd Virginia issued last-minute orders to his jittery men. “Boys, they are coming,” shouted Cummings. “Now wait until they get close before you fire.”

As the Federals came forward, some troops momentarily hesitated to open fire. A number of Confederate troops had stripped off their uniform jackets in the Virginia heat, others were dressed in blue. Union officers had difficulty identifying the enemy. They quickly realized the mistake when the Confederate line erupted in a sheet of flame, ripping apart Federal ranks in a storm of musketry.

A dense pall of smoke covered the field, and neither side could see the enemy except for bright muzzle flashes glimpsed through the haze. The Federals stood their ground briefly, firing five volleys before breaking under the pressure. As Union troops fled for the rear, Ricketts, alarmed that the entire position might be overrun, begged for the infantry to rally. “For God’s sake boys, save my battery!” shouted Ricketts.

Amid the confusion, terror struck. Seemingly from nowhere, a wall of Confederate horsemen, galloping at full speed and quickly closing the distance, was bearing down on the exposed right flank of the 11th New York. It was the 1st Virginia Cavalry, noticeably mounted on black horses, under the command of a spirited young cavalry officer, Colonel James Ewell Brown Stuart. In moments the thundering wall of horses and men crashed into the disorganized Union troops, bowling over Zouaves and tearing their way through the ranks. The swift close-quarters fight was a terrifying experience for men on each side.

“I leaned down in the saddle and rammed the muzzle of my carbine into the stomach of my man and pulled the trigger,” wrote Lieutenant William Blackford of the 1st Virginia Cavalry. “He tried to get his bayonet up to meet me; but he was too slow, for the carbine blew a hole as big as my arm clear through him.”

The three Union regiments that had gone into the attack had been shattered. Nearly 120 of them had been killed in just twenty minutes of fighting. Dazed survivors limped for the rear. The hard-won Union position was coming apart. Desperate to hold the ground, Griffin took two of his guns to the right of the Union line, gambling that he could outflank the Confederates and enfilade their artillery position.

Griffin’s guns bounded across Henry Hill and unlimbered off Ricketts’ right, opening up and oblique fire into the Confederates. Off on his right, Griffin noticed an approaching line of infantry and immediately identified it as the enemy. Major William Barry, McDowell’s chief of artillery, happened upon the scene and disagreed. The approaching line of soldiers was friendly infantry. Griffin was furious. He shouted that he was certain they were Confederates.

It was yet another case of mistaken identity. As Griffin frantically scrambled to get his guns out of the way, the line of oncoming infantry, composed of the 33rd and the 49th Virginia, which belonged to Colonel Philip St. George Cocke’s Brigade, opened fire and made a rush for the guns. The exultant Confederates overran the position, seizing the guns amid a horrifying scene of dead and dying artillerymen.

General Bee had been rallying his brigade in the hope of leading it back into action. As he exhorted the exhausted troops of the 4th Alabama, Bee pointed in the direction of the main Confederate line and uttered what would become immortal words. “Yonder stands Jackson like a stone wall,” shouted Bee. “Let’s go to his assistance!”

Such assistance would be sorely needed as McDowell continued to feed fresh troops at Henry Hill. As the 33rd Virginia and 49th Virginia milled around Griffin’s captured guns, they were abruptly attacked by the soldiers of the 14th Brooklyn, who had worked their way around the Confederate left. From the distance of 100 yards, the New Yorkers poured a devastating volley into the Virginians, who reeled under the fire and hurriedly withdrew.

The Brooklyn men followed in hot pursuit, heedless that they were charging into the teeth of Jackson’s line. As they angled for Confederate guns along the eastern slope of the hill, they came to within 50 yards of the Confederates when they suffered the effects of a close-range volley.

Jackson, nursing a wounded hand, was ready to strike back. He ordered the 4th and 27th Virginia regiments of his brigade to execute a bayonet charge. Ricketts’ artillerymen loaded their guns with canister in an attempt to stop the Confederate charge. Although they suffered heavy casualties as they charged across the open ground, the Virginians pitched into the artillerymen and seized the battery.

But the Federals would need to make a much stronger push if they were to gain a secure foothold on Henry Hill. Colonel William Franklin of Heintzelman’s Brigade decided to make the attempt with his 5th and 11th Massachusetts regiments. As soon as Massachusetts men began their advance, though, they were staggered with heavy gunfire that poured down the hillside. Rather than fall back, the Bay Staters closed ranks and pressed forward. Charging toward the Virginians milling around the Henry House, the Massachusetts men succeeded in driving off the Confederates and retaking Ricketts’ guns.

But the see-saw fight atop Henry Hill was far from over. Determined to take control of the hill, Beauregard rode among the stunned troops of the 5th Virginia, pleading with them to make a fresh attack. “Give them the bayonet!” he shouted. With that, the fiery Creole, who made a conspicuous target on horseback, led the Virginians in yet another charge. Supported by various other Confederate regiments that moved up to add their weight to the attack, they succeeded in driving off the Massachusetts troops around Ricketts’ guns. Beauregard, exultant after the successful charge, was unscathed.

General Bee was not so fortunate. The stalwart brigadier, once again leading his men toward the epicenter of the fighting, was struck by rifle fire and mortally wounded. Bartow was killed outright when he was leading the 7th Georgia. The swirling battle on the hill had transformed the once-pastoral Henry farm into a veritable charnel house. “The shouts of the combatants, the groans of the wounded and dying, and the explosion of shells made a complete pandemonium,” said Private John Opie of the 5th Virginia.

Despite his inability to break through Confederate defenses, McDowell was far from abandoning the fight. He sent Colonel William Tecumseh Sherman’s Brigade, which had not yet engaged the enemy, to make a final attempt to capture Henry Hill. Sherman made a tactical mistake by sending his regiments into action piecemeal.

The first to go was the 13th New York, which advanced on the left, taking cover in low ground near the Henry house. The New Yorkers traded fire with the Hampton Legion, but failed to make any progress. Pinned down by the South Carolinians, they were immobilized and unable to take part in the struggle for the hill.

The 2nd Wisconsin of Sherman’s brigade moved up on the right of the New Yorkers, but the inescapable fog of war cursed them from the outset. Dressed in gray uniforms, the Wisconsin men were immediately mistaken for Confederates; as a result, confused Union troops opened fire into their rear. After officers regained order and stopped the firing, the regiment pushed up the hill once again.

As the Wisconsin men neared the Confederate line, they faced an impenetrable wall of gunfire and fell short of their objective. Caught in the open and ripped apart by heavy fire, they were forced to fall back. As they did so, more horrors awaited. Emerging from the smoke and once again confused for Confederates, the Wisconsin men took a full volley from Federals in the Sudley Road who were convinced that the gray-uniformed troops coming their way were the enemy. Fired on from front and rear, the 2nd Wisconsin withered away.

Sherman’s 79th New York, known as the Highlanders for their Scottish heritage, fared little better. The New Yorkers marched gamely up the hill, only to be met with a murderous volley. The Confederates around the Henry farm were determined to hold onto their prize, and continued pouring heavy fire into the Highlanders. Stalled in a bitter crossfire, the regiment broke for the rear.

Attacks launched by single regiments were clearly going nowhere. On Sherman’s right, the 69th and 38th New York, bolstered by Lt. Col. Albert Monroe’s Rhode Island Battery, were sending a well-directed fire uphill in the direction of the Henry house. The men of Hampton’s Legion and the 5th Virginia, who had been in combat the better part of the day, found the pressure more than they could bear. Breaking under the pressure of the New Yorkers’ combined firepower, the Confederates fell back.

Sensing an opportunity, Sherman personally led the New York regiments straight up the hill, where they rooted out remaining Confederate diehards and took control of the farm. Remarkably, after hours of horrific battle, it initially looked as if the New Yorkers had actually broken the Confederate line. As gray-clad stragglers filed off the field to the tree line to the east, organized Confederate resistance seemed to disappear with them. “We appeared for a time to have complete possession of the field,” recalled Lt. Col. Addison Farnsworth of the 38th New York.

Although a Federal victory seemed within reach, a gray wave was about to break over the Union troops on Henry Hill. While McDowell had repeatedly launched his regiments piecemeal into the battle, only to be chewed up in the

fruitless struggle for Henry Hill, Johnston and Beauregard had been busy rushing troops north from the lower fords. All told, Beauregard was preparing to commit 7,000 fresh Confederate soldiers against McDowell’s exhausted troops.

In a bold effort to drive the federals off of Henry Hill once and for all, Beauregard unleashed two Virginia regiments, the 8th and the 18th, in yet another attack. As the soldiers in the two regiments stepped off to the attack, they picked up strength as retreating soldiers from other regiments joined with them. By the time the Confederates reached the grounds of the Henry House, they constituted an inexorable gray tide that wrecked the weakened Union position.

Crashing into the 69th New York, the 8th Virginia let loose heavy fire and then bowled over the Federals. Just south of the Henry House, the 18th Virginia overpowered the 38th New York. The tide of battle had shifted irreversibly in favor of the Confederates. Demoralized Federal troops streamed down the hill. The majority refused to reform and drifted off to the rear. Keen to secure the hard-won ground, the Virginians plunged into the defile of Sudley Road.

Confederate reinforcements, sweeping around the southern edge of Henry Hill, angled for Chinn Ridge, the commanding heights that dominated the Union right. Reaching the base of the ridge, Colonel Arnold Elzey, who led the Fourth Brigade of Johnston’s army, caught sight of troops along the crest, who turned out to be Federals. The Union troops belonged to Colonel Oliver O. Howard’s Brigade, which was the last intact brigade that McDowell had with which to halt the Confederate advance.

The two sides opened fire, pouring musketry back and forth across the slope of Chinn Ridge. Howard fought with determination, but the weight of Confederate numbers was threatening his position. When he ordered his flank pulled back, his inexperienced troops confused the directive for an order to retreat. The retrograde movement became contagious. As Howard watched helplessly, his brigade evaporated before his eyes.

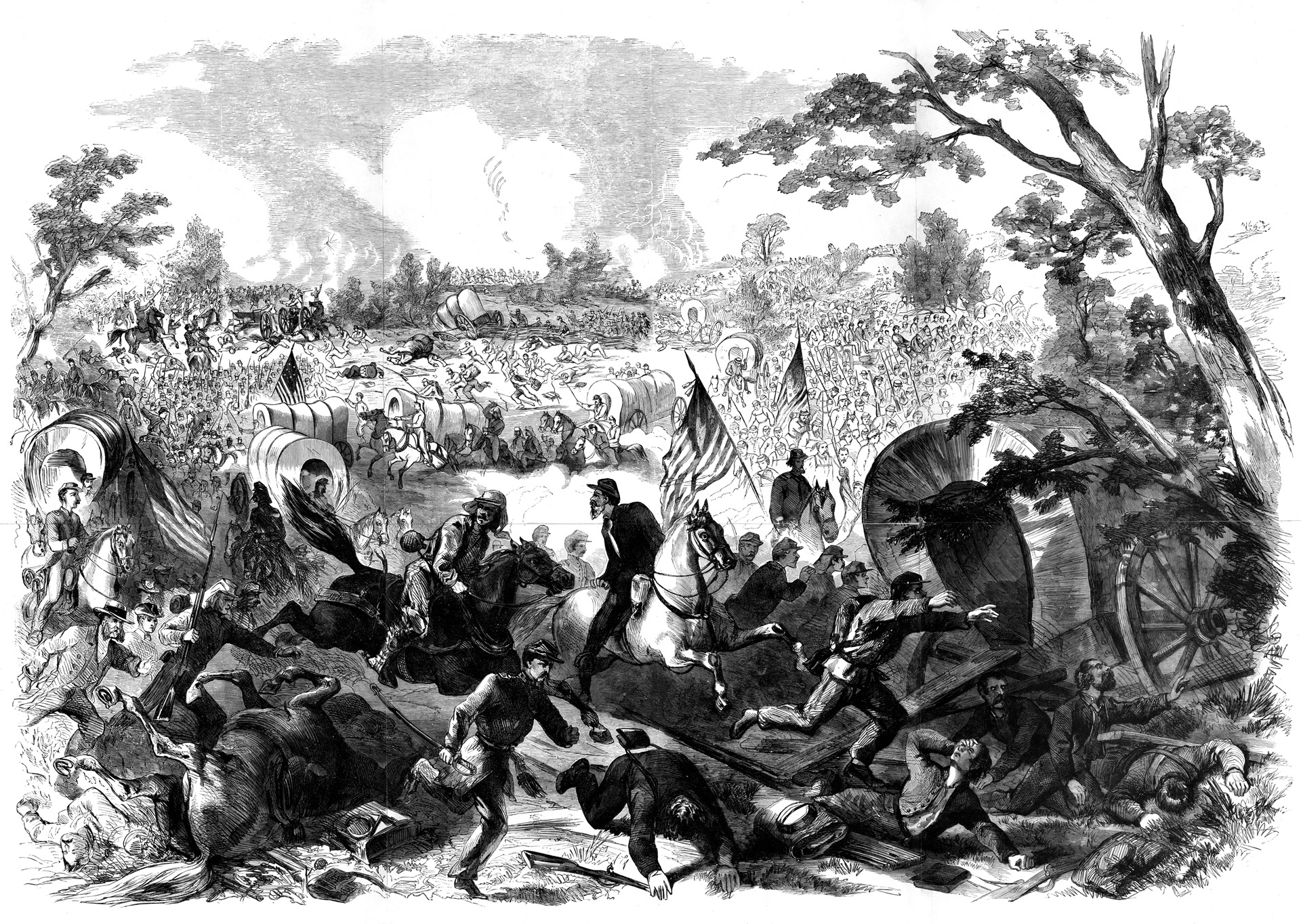

The abrupt collapse of Howard’s troops precipitated the total and sudden defeat of McDowell’s army. Aside from isolated knots of stubborn soldiers who put up a fighting retreat, nearly every Federal soldier able to walk began moving slowly but steadily for the rear. Officers shouted and cursed, but to no avail. The fight had been taken out of the Federals, and they began what was at first an orderly withdrawal towards Sudley Ford.

While McDowell’s beaten troops reversed the morning’s lengthy circuitous march, Beauregard acted to cut off their retreat, sending three regiments across Bull Run to take control of the Warrenton Turnpike. As he advanced north along the turnpike, Colonel Joseph Kershaw, the commander of the 2nd South Carolina, caught sight of an irresistible target. Although the head of McDowell’s column had beaten him to the crossing over Cub Run, the mass of Federals trying to cross the narrow bridge had created a chaotic log jam of demoralized troops.

Kershaw ordered Captain Delaware Kemper’s of the Alexandria Light Artillery to open fire on the bridge. Kemper unlimbered two guns and fired spherical case shot at the bridge. The case shot exploded directly over the target and rained down shrapnel that struck the horses leading the first supply wagon onto the bridge. The panicked horses overturned the wagon effectively blocking the bridge. Terrified men plunged into the water of Cub Run as a general panic gripped the retreating Federals. McDowell’s embarrassing defeat and withdrawal had degenerated to a panic-stricken rout.

As the beaten Union Army streamed north, it made remarkable progress. Not surprisingly, the march from Washington that had previously taken four days was completed in 12 hours by the panicked troops. Despite the vulnerable condition of the enemy, Confederate troops were largely unable to give chase. Johnston’s steady leadership throughout the battle had helped to secure a major victory. The Confederates, though, were “more disorganized by victory that that of the United States in defeat,” he said afterwards.

Although they were in no condition to effectively cut off the Federal retreat, the Confederates were left in victorious possession of the field, as well as a vast haul of booty. They corralled scores of prisoners, among them civilian sightseers and northern politicians. At the bridge over Cub Run alone, Confederates rifled through a rich haul of spoils that included 16 cannon, firearms, supply wagons, and horses.

The human cost was far worse. The battlefield, in particular the vortex of the fight on Henry Hill, was left covered with the dead and dying. McDowell suffered a total of 2,708 casualties, of which 481 were killed. The victorious Confederates likewise suffered badly, with nearly 2,000 casualties and 387 killed.

Tragically, the battle would be dwarfed by far bloodier clashes over the course of the next four years. In the aftermath of the fight at First Bull Run, the nation began to awake to the stark realities of a long and divisive conflict. The Civil War would not be short and relatively painless, but a protracted period of bloodletting the likes of which America had never seen.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments