By Richard Rule

By the time of the waning of the summer of 1944 in western Europe, General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s victorious Allied armies had forged a battle line from the Dutch province of Maastricht in the north to Belfort near the Swiss border in the south. Germany’s military reversals since the breakout from the Normandy beaches had been staggering. Her very borders were now threatened and her army was on the brink of collapse—the Germans faced a catastrophe that no amount of propaganda could disguise.

As August gave way to September, the 1st U.S. Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Courtney H. Hodges, stood poised for the drive into Germany itself. Looming directly in the path of 1st Army lay the ancient German city of Aachen, nestled between two heavily fortified belts of the Siegfried Line near the Dutch and Belgian borders. Although of little military importance to either side, it was nonetheless a town of immense psychological value to the Germans. Aside from being the first major city in the Reich threatened by Allied ground troops, it was also the birthplace of Emperor Charlemagne and the seat of his Frankish Empire, which Hitler considered to have been the First Reich. Its importance to Hodges, however, lay in its significant historical role as the western gateway to greater Germany, a role he expected it to play once again.

In mid-September, elements of 1st Army tentatively probed the city’s defenses. But lacking supplies and potency, they chose to withdraw when confronted with surprisingly stiff German resistance, little realizing how vulnerable the city really was. The mere threat of an American attack had panicked Aachen’s Nazi leadership into hastily commandeering a train for themselves and fleeing. Within hours the city’s entire government had gone, shamefully leaving the people to fend for themselves. An outraged Hitler had Aachen’s leaders swiftly arrested, stripped of their rank, and packed off to perish in the inferno of the Eastern Front.

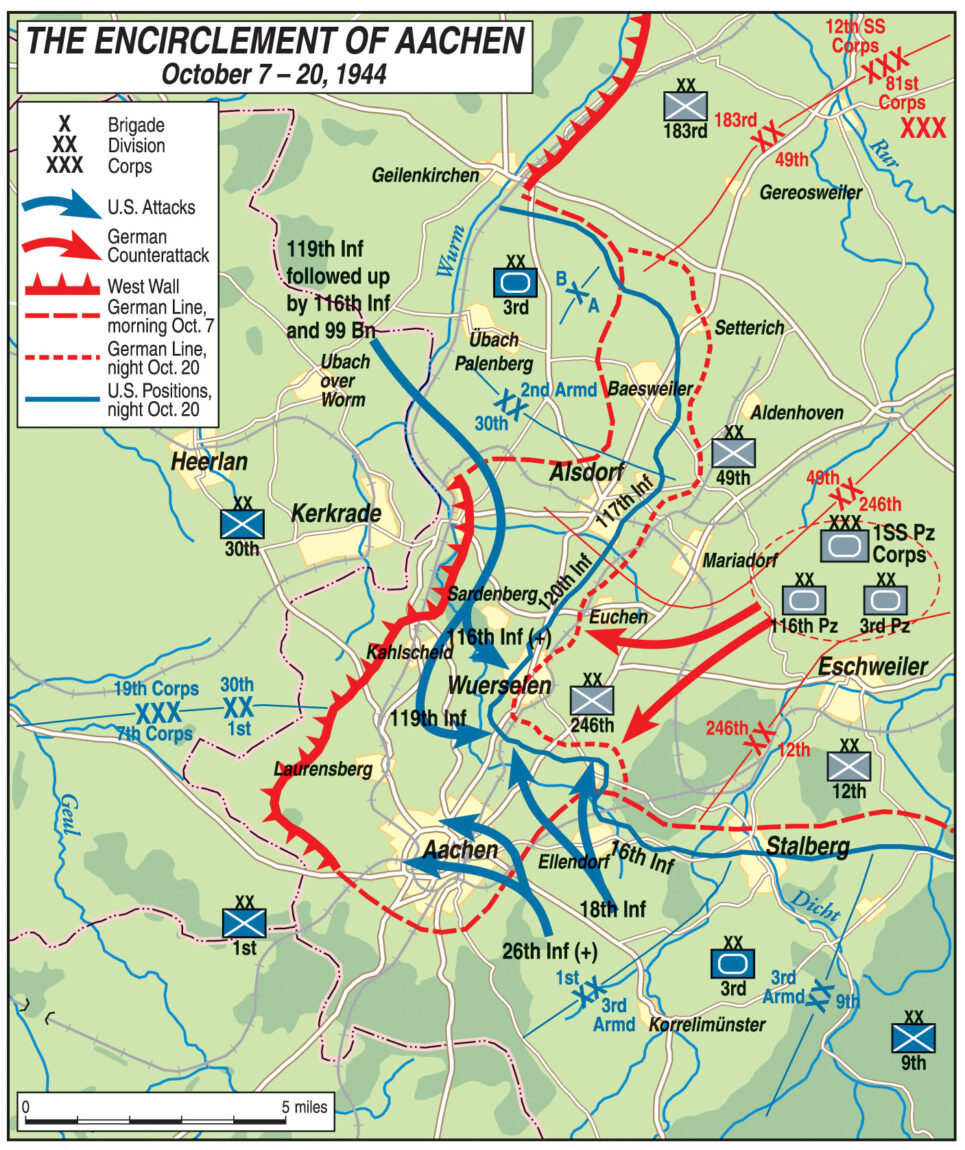

Aachen’s link to National Socialist ideology, coupled with Hitler’s fanatical desire to hold the ancient city, ensured that it would not be given up without a fight. The unenviable task of defending the German frontier at Aachen fell to the 18,000 troops of General Friedrich Koechling’s four understrength divisions comprising 7th Army’s LXXXI Corps. With the 1st U.S. Army expected to return in strength any day, Koechling wasted no time deploying his forces in a defensive ring around the city. The 183rd Volksgrenadier and 49th Infantry Divisions took up positions in the north, the veteran 12th Infantry Division was placed along the southeastern outskirts, and the remains of the battered 246th Volksgrenadier Division would defend the city limits of Aachen itself.

Two veteran panzer divisions would provide further support during the first week of October, strengthening Koechling’s positions with 24,000 additional troops and substantial armor. With such a force at his disposal the aggressive Koechling was confident he could hold the Americans; but where would his enemy strike?

At 57 years of age, 1st Army’s commander Hodges was one of only a handful of U.S. generals to have seen war from the sharp end, having served as an infantryman in World War I. He was a tall, impressive-looking officer, known as a meticulous planner who stayed “right on top of the corps and divisions” to make sure they carried out his orders.

As anticipated, his September probes were to be followed up in early October with a more concerted offensive. Mindful of his diminishing logistical capability, Hodges planned to capitalize on the turmoil in the enemy camp by quickly breaking through the Siegfried Line along the narrow Aachen corridor, between the Ardennes and the Fens of Holland. Aachen, however, would not be the main objective. To avoid the snare of costly house-to-house combat, General Hodges would drive his forces through the Siegfried Line at points north and south of Aachen before linking both wings to the east, effectively encircling and isolating the town. The bulk of 1st Army would then press to the Rhine, leaving Aachen to wither. In one of the war’s great ironies the invasion of Germany would, in fact, encompass all the hallmark characteristics of “Blitzkrieg” warfare: rupturing of the enemy’s main line of resistance; bypassing a city considered an obstacle rather than an objective; and exploiting the enemy rear area.

The 1st Army’s XIX Corps would lead the first set-piece attack against the vaunted Siegfried Line. The Corps’ 30th Infantry Division, commanded by General Leyland Hobbs, would ford a small river nine miles north of the Imperial City, then storm the Siegfried Line along a one-mile front between Rimburg and Marienberg. Once Hobbs’ infantry had cleared a path through the German line, the entire 2nd Armored Division would join the attack, creating an armored shield along Hobbs’ northern flank as he advanced east of Aachen. With the aim of encircling the city, Hobbs planned to link up with VII Corps’ 1st Infantry Division, which would breach the Siegfried Line below Aachen and push north. The ring would be cemented at the village of Wuerselen.

It was a simple plan and, after a number of postponements, H-hour was set for 11 in the morning of October 2. To soften the German defenses, as early as September 26 artillery batteries had begun to systematically pummel pillboxes along the 30th Division front, and a massive saturation airstrike was to follow.

But from the outset things did not go according to plan. With D-day fast approaching, ground observers were disappointed with the results of the elaborate artillery program. Other than to strip off camouflage, clear a few minefields, and blow away some of the wire obstacles, the shelling appeared to have had no appreciable effect on the pillboxes—most had survived the firestorm intact.

Then the pulverizing 450-plane air strike, for which there were high expectations, fared little better. Through a combination of poor navigation, low visibility, and inexperience, the 360 bomber crews located very few of their targets while the fighter-bombers did not register a direct hit on any of the pillboxes. It was a dismal performance compounded by an instance of gross navigational error: A Belgian mining town 28 miles from the target area was accidentally bombed, killing and wounding 90 civilians.

In spite of the avalanche of bombs (including the use of napalm for the first time) it became clear that, as had been demonstrated in Normandy, the margin for error in coordinating large-scale air and ground force attacks had proved too difficult to overcome.

Despite the failure of the preliminary bombardments, Hodges would not tolerate further postponement. With the 30th Infantry Division irrevocably committed to the assault, the troops braced themselves against the chill of an early winter, under no illusions about the grueling slog that awaited them now that the Germans were fighting on their own soil.

At 11am on October 2, under leaden skies, the invasion began as 400 big guns and mortars commenced a rolling barrage that swept a curtain of high explosives ahead of the 30th Infantry Division. With .50-caliber machine guns firing tracer over their heads, Hobbs’ troops stormed across the Wurm River into Germany, the first invaders to do so in over 300 years.

The German pillbox crews, demonstrating considerable fire discipline, quickly opened up an unrelenting volume of counterfire that took a steady toll on the advancing infantry. The defenders called down their own artillery to join the avalanche of American shells that screamed overhead like freight trains, transforming both banks into a seething mass of earth, water, and fire. Through a surreal world of smoke and shrapnel, men attacked, men defended, while many fell never to rise again.

Having run the gauntlet across the river, the GIs and combat engineers methodically set about the task of subduing the nearly 50 enemy strongholds in their path. During the Normandy landings the Americans found that the German pillbox crews fought well while the action was in front, but when attacked from the rear they would often surrender. Drawing on this experience, the troops made every effort to work their way behind the German installations to blow the rear doors with Bangalore torpedoes, satchel charges, or bazookas.

There was no respite in this bitter, frightful battle, but as the first harrowing day drew to a close, General Hobbs’ men had successfully pierced the first line of pillboxes, gaining a narrow bridgehead along the whole of their front. As dusk approached the exhausted troops dug in and waited apprehensively for what the coming night would bring.

The German commanders in the region, deceived by diversionary attacks 10 miles to the north, were slow to grasp that the 30th Division thrust across the Wurm was, in fact, the main effort. The subsequent German response amounted to a feeble halfhearted counterattack that was easily driven off. Thus on D+1 with the enemy in disarray, Hobbs had achieved a toehold into Germany itself. The following day he would exploit his gains, commencing his drive to Wuerselen.

Reports of the American attack sent shock waves through the German command. General Koechling had wrongly anticipated that the main attack would be directed southeast of Aachen; thus, his counterattack had neither the manpower nor the armaments for the job and it fell short. He then poured his entire corps’ artillery onto the American positions to try to contain the bridgehead. This, too, failed. For the next three days American troops, now supported by the 2nd Armored Division, relentlessly battered their way through the German line.

By October 7, XIX Corps had chiseled a clean break through the Siegfried Line six miles wide and to a depth of nearly five miles. Having lost 1,800 men and 52 tanks, XIX Corps had established a line north of Aachen from Alsdorf through Beggensdorf to Geilenkirchen, bringing a successful conclusion to the first set-piece attack against the West Wall.

Thus the stage was set for the next round. General Clarence Huebner, commanding the 1st Infantry Division, planned to attack through the Siegfried Line southeast of Aachen one hour before dawn on October 8. With Hobbs making steady progress, Huebner was confident the “Big Red One,” as the 1st Infantry Division was known, would not keep them waiting.

Wuerselen was only 21/2 miles from the 1st Infantry Division lines, but the men of the 18th Infantry Regiment spearheading the assault would be attacking over deadly ground. Intelligence reports indicated that the Americans would be up against a well-entrenched enemy fighting from within thoroughly prepared defensive positions. The regiment’s first hurdle would be the village of Verlautenheide sited in the second belt of the Siegfried Line and bristling with pillboxes, interconnecting communication trenches, gun pits, and foxholes. The next objective, 1,000 yards northeast of Verlautenheide, was the well-defended crest summit known as Crucifix Hill (Hill 239), while the final goal was the well-fortified Ravels Hill (Hill 231).

By putting into practice lessons learned in earlier pillbox fighting, the division prepared itself by undertaking intense training to perfect the use of artillery and air support in combination with special assault teams equipped with flamethrowers, Bangalore torpedoes, and various pole and satchel charges. To take and hold these positions was a difficult prospect, but as events unfolded Huebner’s thorough preattack planning and rigorous training paid off.

The linking of an uncustomary predawn attack with a massive preliminary artillery bombardment paved the way for the quick capture of Verlautenheide. Most of the German defenders, caught off guard by the night attack, were taken prisoner before they realized what had happened. The second objective, Crucifix Hill, was overrun in an hour, while the following night the 65-man garrison atop Ravels Hill was captured without a shot being fired. In a stunning operation, the division had captured all three primary objectives in less than 48 hours.

In a customarily violent response, the Germans sent a massive artillery bombardment crashing down upon the exposed American troops grimly holding their new positions; veterans would later recall this as being the heaviest barrage they had ever endured. In spite of mounting casualties, Huebner was confident his men could hold on until the 30th Division arrived to seal the gap around Aachen. But in the bleak, urbanized, coal-mining country a few miles to the north, the pendulum had swung back in favor of the defenders. The Germans had dug in their heels and were making a stand.

The energetic Field Marshal Walther Model, who commanded Axis forces in the Ruhr pocket, arrived at General Koechling’s headquarters to evaluate for himself the situation north of Wuerselen. Model, no stranger to a military crisis, could see that while Koechling’s men had finally checked the 30th Infantry Division’s drive to Wuerselen, their resolute defense could not hold indefinitely. In his characteristically blunt manner, he reported to Commander-in-Chief West Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt that unless reinforcements were sent, “continued reverses will be unavoidable.” This was not an exaggeration—the only hope of breaking the noose tightening around Aachen rested with a series of quick, decisive, powerful counterattacks.

Von Rundstedt immediately dispatched the 116th Panzer and 3rd Panzer Grenadier divisions to Aachen. The situation around the city was in fact so serious that Model took the desperate measure of committing these panzer forces to battle piecemeal; the men were virtually proceeding straight into battle from the railway platform.

The mood in the 30th Infantry Division camp north of Aachen had grown similarly desperate. Their attack, which had started so promisingly two weeks earlier, was bogged down three miles short of their objective. In the face of fierce German counterattacks, Hobbs’ drive had been ground to a halt—his troops had not advanced a single yard in five days.

An impatient General Hodges, who felt Hobbs was always “either bragging or complaining,” made it clear he expected the 30th Infantry Division to broaden its effort with a general attack all along the line. It seemed clear to Hobbs that neither Hodges nor his staff fully appreciated the adverse nature of the country across which his men were fighting. The Germans were fully exploiting a hideous landscape honeycombed with mine shafts, slag piles, and small villages tailor-made for defense. Having already suffered over 3,000 casualties, mostly riflemen, Hobbs was reluctant to commit his exhausted troops to a frontal assault that would achieve little. Under enormous pressure to keep his job, he had to find another way to quickly close the gap with the 1st Division.

Although Hobbs and his staff bore the brunt of much criticism, the reality was that no one, least of all Hodges, had anticipated the Wehrmacht’s ability to recover its balance so quickly. The Germans were not only able to delay the American push to the Rhine, but were also siphoning off sorely needed troops and supplies that would have far-reaching consequences on Hodges’ offensive capabilities in the weeks ahead.

A further frustration for Hodges lay with the substantial German force left bottled up in Aachen, which posed a threat to the supply lines of future Allied operations. Hodges had little choice but to hand the 1st Infantry Division the task of clearing them out. Even though the city was yet to be completely surrounded, Huebner wasted no time issuing an ultimatum giving the German commander 24 hours to surrender. But in accordance with Hitler’s “last stand” orders, the demand was immediately rejected; if the Americans wanted Aachen, they would have to take it by force of arms.

Wresting the city from the Germans created some vexing problems for Huebner. Having been hit hard in his rifle companies—a 70 percent turnover since D-day on June 6—he was spread thinly along an elongated front and felt compelled to hoard his precious reserves in anticipation of a major German counterattack. Short of manpower, he was able to spare only two battalions of Colonel John F.R. Seitz’s battle-hardened 26th Infantry Regiment for the assault on Aachen.

Although outnumbered by the enemy troops defending the city, the 26th fortunately would be vastly superior in armor, artillery, and air support. Even so, the regiment found itself in the unenviable position of taking on a very complicated assault with the very real possibility of having to disengage or hold in place at a moment’s notice. As the regiment’s G-3 recalled, they would be attacking with “one eye cocked over their right shoulder” in the likely direction of the German counterattack.

In one of the classic small-unit actions of the war in Europe, Seitz planned to concentrate his forces by attacking through the city from east to west with both battalions’ lines abreast. His 2nd Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Derrill Daniel, would sweep through the heart of Aachen toward the west. The 3rd Battalion on the right, commanded by Lt. Col. John T. Corley, would strike northwestward through a maze of factories and apartment buildings to seize Farwick Park and the three hills within that dominated the northern fringes of the city. The bulk of this hill mass known as the Lousberg (the Americans were to know it as Observatory Hill due to the observation tower on its peak) towered to a height of 862 feet, casting a shadow over almost the entire city. By seizing these heights, the Americans believed they could take the whole city under fire.

But the principles of village fighting would come as a shock to American troops who had just swept at breakneck speed across France. It was a fighting discipline in which they had very little practical experience. Daniel surmised that the Germans, being experienced house-to-house fighters, would exact a heavy toll for every building, house, and cellar if his planning was not thorough and his men not fully prepared. He firmly believed that sweat in preparation would save 2nd Battalion blood in combat.

With an attack frontage of approximately 2,000 yards, Daniel set about organizing his battalion into a series of combined-arms’ company teams with each rifle company receiving three Shermans or Tank Destroyers and two antitank guns. Following his commander’s lead, Daniel decided to put all his platoons forward and fight without a reserve. Companies and platoons were assigned specific missions to ensure they coordinated their actions and maintained contact by establishing checkpoints and phase lines based on streets and prominent buildings; no one advanced beyond a checkpoint until contact had been made with their neighboring unit. To further orchestrate his combat power, Daniel would have artillery and mortar fire striking deep across the front to isolate the battlefield, while heavy machine guns were trained down the main streets and intersections to hinder German lateral movement.

Supported by a mobile ammunition dump following close behind his front lines, Daniel encouraged the men to make use of their overwhelming firepower at all times, including demolitions, flamethrowers, and bazookas to overcome any German positions that proved particularly difficult. This was the first major street-fighting battle the American army had undertaken in Europe and, in spite of heavy air-raid damage, the troops of the 2nd Battalion adopted the motto, “Knock ’em all down,” highlighting their readiness to destroy what was left of Aachen if necessary.

When the surrender ultimatum expired on October 11, 300 P-38 and P-47 fighter-bombers from IX Tactical Air Command opened the attack, winging in from the east to plaster predetermined targets along the city perimeter. Soon afterward 12 battalions of VII Corps and 1st Division artillery further pounded the German defenders with a thunderous bombardment, sinking the city center beneath a shroud of choking black smoke and dust. As shells and bombs rained down, the 20,000 civilians who remained in the city cowered in their cellars and air-raid shelters fearful that their once-proud city, like so many others across Europe, would soon be little more than a smoldering skeletal ruin.

During the wet, cold night of October 12, a lone German staff car stole into the besieged city, delivering Colonel Gerhard Wilck to retake command of the 246th Volksgrenadier Division. The new battle commandant of “Fortress Aachen” was an experienced yet unremarkable 49-year-old officer who carried orders to hold the city to the last man. As further insurance Wilck had been forced to sign a formal document empowering the Gestapo to arrest and execute his wife and children if he surrendered.

Arriving at his command headquarters within the city’s former luxury hotel, the Palast-Hotel Quellenhof, Wilck pored over a large-scale map of Aachen as his staff officers dutifully briefed him on the current situation. It wasn’t encouraging. He had always known that the city would be very difficult to defend; the hills that surrounded it would allow his enemy to look down on him at all times, while their aircraft roamed the skies unmolested. Although his immediate threat came from Colonel Seitz’s 26th Infantry Regiment, which stood poised to attack, Wilck was also very concerned by the U.S. 1st Infantry Division entrenched to the south and the 30th Infantry Division battling hard north of Wuerselen. The former tactics teacher could see that if these two divisions linked up, as was their intention, the garrison would be surrounded. Wilck and his men would be trapped.

The 246th Volksgrenadier Division under his command had already suffered horrendous casualties during the fighting of the preceding weeks. Those of its soldiers who were left to take on the onerous task of defending “Fortress Aachen” amounted to a grab bag of poorly trained ex-sailors, policemen, and Luftwaffe personnel, supplemented by an assortment of teenage paratroopers and Wehrmacht regulars. For fire support the garrison could muster only a handful of Mark IV tanks, armored personnel carriers, and assault guns complimented with a few batteries of artillery.

Clearly lacking the firepower to compete with the American artillery and armor, Wilck privately doubted he could hold if the Americans came in force, but nonetheless he set to work marshaling and deploying his forces as best he could. Just before dawn the following morning, an exhausted Wilck received a communiqué from 7th Army Headquarters: “Hold out. Large scale help on its way.” Little did he know that for once the message was true. With the onset of first light he waited for the coming onslaught, fearful that his first day in command might well be his last—it was Friday the 13th.

Colonel Daniel’s 2nd Battalion finally received orders to move up to its jumpoff line along a high railroad embankment on the outskirts of the city. At 9:30 am on October 13, every soldier in the battalion hurled a grenade into the German front line, then attacked after the explosions, shouting and firing as they came—the ground assault on Aachen was under way.

Resistance was initially light, but the crust of the German defenses became appreciably tougher the farther into Aachen the Americans moved. The fighting quickly fell into a pattern as the GIs set about the painstaking task of grinding down the enemy defenses—street by street, house by house, cellar by cellar. As they had rehearsed, tanks would keep each building under fire until the infantry moved in to engage the occupants. Tossing a grenade through a door or window, the troops would rush in after the explosion to spray the room and upper floors with automatic fire, then use grenades or verbal persuasion to induce the Germans in the cellars to surrender. The tanks, meanwhile, would shift their fire to the next building.

Through the bitter experience of taking casualties from the rear, the GIs quickly learned that it was best to do one building at a time, ensuring that every room, closet, and cellar had been checked for stragglers. They had learned the hard way that the key to street fighting lay in persistence, not speed. As Daniel had hoped, a coordinated German response was hamstrung by American big guns disrupting enemy communication lines inside the city, while light artillery and mortar shells pounded German positions several streets ahead of the Americans. It was, in fact, one of the few times in the European war that American artillery was in a position to fire parallel to the front, landing shells just ahead of the attacking infantry without danger from “drop-shorts.” To maximize the damage, artillerists began using delayed fuses that allowed shells to crash through several floors before exploding among the Germans sheltering in the cellars.

In spite of these difficulties, the men of the 246th fought back with determination. The troops doggedly held onto virtually every stronghold until either killed or driven out. With marauding Allied fighters swooping on anything that moved above ground during daylight hours, Wilck began shuttling his men through the city sewer system to launch unexpected counterattacks in the American rear areas. The tactic proved so effective that the exasperated GIs were forced to go down into the sewers to root out the Germans, then seal every manhole along their line of advance to prevent further infiltration.

The fighting was reduced to a slogging, barricade-type warfare where opposing troops were often close enough to hurl verbal abuse at one another from across the street, or from floor to floor. The constant threat of snipers, coupled with the unrelenting nervous strain of close-quarter battle, ensured neither side would take any chances, choosing to shoot first and ask questions later.

But as the hours passed it was clear the American’s potent mix of planning, tactics, and firepower were relentlessly forcing the Germans back toward the city center. As night descended on the first day, Colonel Daniel pivoted his 2nd Battalion to the left, perpendicular to his original starting position—his three companies on line would attack westward toward the city center.

Meanwhile Colonel John T. Corley’s 3rd Battalion drive west toward Farwick Park and the high ground of the Lousberg was almost immediately blocked by German troops holed up inside the St. Elisabeth Hospital and Technical College in the Blucherplatz. The Germans had quickly knocked out two of the supporting Shermans with Panzerfausts and were raking the street with a 20mm antiaircraft cannon deployed in a ground-support role. With small-arms fire also pouring from nearby apartment blocks along the Julichstrasse, the 3rd Battalion found itself engaged in heavy fighting where gains were measured in “buildings, floors, and even rooms.”

As the battle unfolded, Corley discovered that the sturdy, masonry apartment buildings sheltering many of the defenders were virtually impervious to tank shells. So to break the deadlock he brought up a self-propelled 155mm rifle to clear a path. Success was immediate as the big weapon’s first shell sent one of the ancient, stone-walled buildings crashing to the ground. The vibrations from the thunderous explosions could be felt at Wilck’s headquarters over half a mile away. The huge siege gun proved so successful that one was sent to support the 2nd Battalion.

Shell after shell pounded into the German strongpoints in the Blucherplatz until the dazed and shocked survivors finally stumbled out to surrender. With resistance broken, Corley’s men once again continued toward their high-ground objective, where two companies combined to overrun a strongpoint at the St. Elizabeth Church. The momentum carried one of the companies a few hundred yards past the holy site and into Farwick Park itself, not far from the Germans’ headquarters. Wilck, already shaken by the thunderous impact of the 155mm, was shocked by the sudden appearance of American troops so close to his command post. Fearing he was on the verge of being overrun, a distressed Wilck called his superiors for reinforcements. General Koechling immediately rushed a convoy of assault guns and a half-strength Waffen SS battalion to Wilck’s position. Wilck, meanwhile, had hastily transferred his command post to a four-story air-raid shelter in a less threatened part of the city.

By noon the following day, Colonel Corley’s forces in and around Farwick Park had silenced the enemy troops defending the park’s outbuildings. The only obstacle between Corley’s men and the key heights beyond was a band of German paratroopers stubbornly holding out behind the sturdy walls of Wilck’s former headquarters at the Hotel Quellenhof. But then, while bringing up his 155mm rifle to blast the Germans into submission, Corley suddenly found himself thrown onto the defensive. A counterattack by the recently arrived SS troops, supported by assault guns, drove Corley’s two companies back from the northern edge of Farwick Park. The situation could have been worse had it not been for a lone American mortar man with a radio, unseen by the Germans, who courageously remained behind to direct a heavy and accurate mortar barrage that blunted the attack. By late afternoon the German assault had run out of steam, but the aggressive blow had netted them 35 prisoners and given the Americans a serious setback.

Corley’s plans to retrieve the lost ground with a counterattack of his own were thrown into confusion by the sound of big guns outside the city, quickly followed by frantic messages ordering him to hold in place. The SS attack on his men had been the first stage of General Koechling’s two-pronged counterattack. The main effort to break the encirclement of the city rested with the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division’s attack launched against the 1st Infantry Division’s linear defense near Eilendorf. The fierce fighting that ensued “shattered nerves at more than one echelon of command” as grenadiers, supported by tanks, relentlessly hammered away at the American positions in an all-out attempt to break through to the city.

As the hours passed it became clear that the 1st Division line would hold—its artillery was blasting apart waves of German infantry surging forward. But the few lumbering Tiger tanks that managed to batter their way through were able to inflict casualties of their own, firing into the fox-hole lines at close range.

For two days the Germans pressed their attacks in the face of fierce artillery and fighter-bomber assault. Finally, late in the afternoon of October 16, with the ground in front of the American lines littered with hundreds of German dead and wounded, the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division retired—they had lost over one third of their combatants and most of their tanks. Thus the abortive counterattack to relieve Aachen had been a costly failure.

As the sound of battle subsided near Eilendorf, a desperate General Hobbs was planning a daring maneuver to break the deadlock north of Wuerselen. With his career in the balance, Hobbs pinned everything on an operation that, if successful, would outflank the Germans and push through to 1st Division lines at Ravelsberg. Hobbs knew there could be no half-measures, it would be “root-hog or die!”

At 5 in the morning of October 16, two battalions of 30th Division infantry were sent across the Wurm River, one moving south along the west bank while the other crossed the Aachen-Wuerselen-Linnich highway northwest of Ravelsberg along the east bank. The hours passed slowly as the infantry edged toward their objective, fighting local German counterattacks nearly all the way. Hobbs could barely contain his anxiety as he waited for news of his soldiers. Finally, 1st Division troops at Ravelsberg reported spotting Hobbs’ men moving near the southwestern fringe of Wuerselen, a mere 1,000 yards away.

Thus at 4:15 in the afternoon of October 16, the ring around Aachen was closed. The linkup was only tenuous, but Huebner nonetheless made preparations to quickly bring this long and costly battle to a close.

The Germans were not passive, however. Koechling was readying his 3rd Panzer Grenadier and 116th Panzer Divisions for a last-ditch attempt to break the Allied cordon in the area of Verlautenheide and Ravelsberg. If it failed, the city’s fate and quite possibly his own were sealed. He hastily conceived his plans, which lacked coordination, and many of his staff believed the attack stood very little chance of breaking through.

Nevertheless, on October 18, Koechling sent his divisions toward Aachen. They fought heavy engagements, but they could not make progress against the well-entrenched Americans. By nightfall of October 19 the German commanders could see that a genuine breakthrough was unlikely and thus withdrew their mauled divisions—Wilck and his garrison had been effectively abandoned to their fate.

With the city now completely surrounded and American forces squeezing from all sides, even the most fanatical German defenders could see that all was lost. For the purpose of propaganda, the defense of Aachen had become a symbol of defiance, much the same as Stalingrad had been for the Russians, but many in command found Wilck’s radioed messages of bravado unconvincing. Von Rundstedt, believing Wilck to be on the verge of capitulation, felt compelled to remind Aachen’s commandant of his duty “once more and with the utmost emphasis to hold this venerable German city to the last man, and, if necessary, allow himself to be buried under its ruins.”

So the fighting went on. With the end in sight, the tempo of the American attack rose as General Huebner reinforced the 26th Infantry with two battalions of tanks and armored infantry from the 3rd Armored Division. These additional units were to join the fight on the northern flank of Colonel Corley’s 3rd Battalion against the enemy troops holding out on the Lousberg Heights. With these reinforcements on line, the 26th Infantry renewed its assault to capture what was left of Aachen. In Farwick Park, Corley quickly reclaimed the ground lost in the SS counterattack three days earlier, then turned his attention to the paratroopers still defiantly holed up in the Hotel Quellenhof.

Preceded by a heavy artillery bombardment that had driven the Germans into the hotel’s basement, a platoon stormed through the marble-floored lobby to clear them out. The paratroopers quickly rose from the basement to meet the threat, leading to a bitter struggle typified by close-quarter combat and running hand-grenade duels through the hallways and rooms. Relentlessly forced back, the desperate Germans began throwing empty champagne bottles when their grenades ran out, but with machine guns now pouring fire directly into the basement, the surviving paratroopers had finally had enough. With arms raised, the battle-worn youths filed out to surrender—the once resplendent Hotel Quellenhof had finally been captured.

Against minimal resistance, Colonel Corley’s forces quickly pushed on to overrun the heights of the Lousberg. With Farwick Park and its outbuildings now firmly in American hands, and Colonel Daniel’s 2nd Battalion having secured all of the downtown area, the fall of the city would be only a question of time. Inside a perimeter reduced to less than a solitary square mile, German troops still grimly defended from among the ruins. After touring his front lines, Wilck radioed to his superiors that “the battle group is defending itself stubbornly around the Lousberg against an enemy who is attacking on all sides.”

Wilck knew that, with the Americans now holding the commanding heights overlooking the city, the end would be swift. In total despair, he issued his final orders, “The defenders of Aachen will prepare for their last battle. Constricted to the smallest possible space, we shall fight to the last man, the last shell, and the last bullet, in accordance with the Fuehrer’s orders.”

His exhortations did little to forestall the end. During October 19 and 20 resistance inside the dying city rapidly crumbled. Many troops now cut off in isolated pockets without food or water began to lay down their arms. Others chose suicide. On October 20 the remaining Germans doggedly holding out around Wilck’s command post braced themselves as Colonel Corley brought up his 155mm artillery piece. Firing from a point-blank range of less than 300 meters, the enormous shells systematically demolished the defenses surrounding the bunker at the northern end of Lousberg Strasse.

On October 21, following a harrowing night of close combat around his headquarters, Wilck radioed his superiors: “All ammo gone after severe house-to-house fighting. No water and no food. Enemy close to command post of the last defenders of the imperial city.” A few minutes later the radio was destroyed; Aachen was now completely cut off.

With the shells of the 155mm now tearing into the bunker itself, Wilck finally dispatched two American prisoners to convey his willingness to capitulate.

Two hours later, on a bright, clear autumn morning, Colonel Wilck led 400 of his troops to Colonel Corley’s battalion headquarters where he formally surrendered—at 12:05 in the afternoon of October 21 the 10-day battle for Aachen was over. By nightfall the remaining German troops scattered throughout the city had been rounded up.

Aachen was the first major German city of the Reich to fall, a prize that after the fighting lay buried beneath 4 million cubic meters of rubble. Having suffered over 6,000 casualties, 1st U.S. Army’s experience on German soil hammered home the harsh fact that the Allied road to final victory would be long and miserable.

For their part, the German casualties were appalling. But many—including Allied commanders after the war—believed that their delaying action was something of a defensive victory. Not only had it bought valuable time to bolster their main belt of defenses beyond Aachen, but it had also served as a perfect screen for the massing of large German forces west of the Rhine. These forces would soon spearhead Hitler’s Operation code-named “Wach am Rhein,” which set off the Battle of the Bulge.

Nice map.