By David A. Norris

“Soldiers, don’t fire!” In the half light of dawn on April 19, 1775, war was breaking out on a New England town common, and Major John Pitcairn of His Majesty’s Marine Forces was trying to stop it. For several tense minutes, Captain John Parker’s company of militia blocked British troops who intended to march through their home town of Lexington, Massachusetts. Someone pulled a trigger. No one saw who fired that shot, but everyone heard the explosion. In defiance of their orders, first one, then another, redcoat fired back. Separate shots blurred into a steady thunder. “Soldiers’ don’t fire! Keep your ranks, form, and surround them!” shouted Pitcairn. Again and again, the major hacked down with his sword, trying to deflect musket balls into the short grass instead of into American subjects of their mutual sovereign, King George III.

Pitcairn, in command of 600 British marines, arrived in Boston in late 1774. He found a city in the throes of chaotic social upheaval and practically under military occupation. Disputes over taxation and British governance of the 13 colonies on North America’s Atlantic Coast started after the end of the French and Indian War in 1763. Boston was such a notorious hotbed of protests against British policies that the Crown sent extra troops to the city in 1768.

As the Crown essentially ignored the colonists’ protests, as well as potential solutions to the disputes, friction grew between dissident colonists and London. On December 16, 1773, a mob of colonists made a violent protest against England’s tea tax. Boarding three ships, the colonists dumped their cargoes of British East India Company tea.

In retaliation for the destruction of the tea, Parliament passed the Boston Port Act. The act banned ships from entering or leaving the port until the tea was paid for. Other laws, collectively called the Intolerable Acts, accompanied the Boston Port Act. Colonial officials would be appointed by the Crown, and Americans arrested in Massachusetts for antigovernment activities would be tried in England. Four thousand more British soldiers were sent to the city, and Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage became the military governor.

The 13 American colonies, founded and governed separately, had quite varying economic interests and social makeups. Parliament’s heavy-handed response aroused sympathy for Massachusetts among the other Atlantic colonies and focused their anger against London. Dissatisfaction with royal policies inspired the establishment of the First Continental Congress, which convened at Philadelphia on September 5, 1774. Fifty-six delegates from 12 colonies (all the 13 colonies except Georgia) discussed how the colonies should proceed together. The meeting also laid the foundation of a governmental authority that would one year later unite the colonies against the Crown.

Meanwhile, the General Court (the Massachusetts legislature) was shut down by Gage. Ninety members met again, under the title of the Provincial Congress. At the head of this illegal body was its president, John Hancock of Massachusetts.

Royal officials saw the possibility of armed rebellion and knew that settlers in the Atlantic colonies had ample means for resisting the British. Based on medieval English precedents, the English colonies provided for their own defense with a universal part-time militia. Regulations varied according to time and place, but generally speaking, all male citizens of military age (from perhaps 16 or 18 up to perhaps 50 or 60) were required to enroll in the militia. A few times a year, companies mustered in for short training sessions, which created a pool of tens of thousands of potential soldiers. In the event of an Indian war, pirate raid, or other civil disturbance, a proportion of each unit was sent for active service with colonial or British forces.

Although the rank and file provided their own clothing, muskets, and accoutrements, local governments distributed gunpowder. Powder was difficult to procure in quantity because it was imported from Britain. From guarded forts or locked royal magazines, the British issued supplies of powder for each town.

William Brattle, an appointee of the royal governor, was in charge of a magazine at Quarry Hill west of Boston. He wrote to Gage, informing him that nearby towns had removed all of their allotments of powder, leaving nothing but the Crown’s share. Lest the remaining powder fall into the hands of rebellious patriots, Gage took action.

On September 1, 1774, Gage ordered 260 armed soldiers to march to Quarry Hill and bring the gunpowder back to Boston. The troops seized 250 half-barrels of powder, which they brought back to the city. A detachment returning by a different route stopped in Cambridge to seize two cannons.

Gage’s act and the reaction to it became known as the Powder Alarm. A harmless and legal action on the part of the British, the Powder Alarm made many colonists believe that the British did not trust them, and that the powerful British Army was in Boston to move against Massachusetts rather than protect it.

During the winter, Patriots spirited weapons and supplies out of Boston. Lieutenant Frederick Mackenzie of the Royal Welch Fusiliers noted on January 30, 1775, that the country dwellers were “taking every means to provide themselves with Arms; and are particularly desirous of procuring the Locks of firelocks, which are easily conveyed out of town without being discovered by the Guards.” Two days later, a court martial in Boston tried some soldiers suspected of selling muskets and locks to civilians. One soldier was convicted and sentenced to receive 500 lashes. Mackenzie wrote that late in March, guards stopped a “countryman” taking 19,000 musket cartridges. No one knew how many other smuggled shipments went undetected.

Well aware of the Patriots’ growing collection of munitions, Gage looked for officers who could produce useful sketches and maps of the towns and roads outside Boston. Among the officers sent out on such missions were Captain John Brown and Ensign Henry D’Berniere. They left Boston in late February, pretending to be surveyors. D’Berniere wrote that they went out “disguised like countrymen, in brown clothes and reddish handkerchiefs round our necks.”

Brown and D’Berniere often felt suspicion and hostility on their trip. Most locals openly supported the Patriots and intimidated the relatively small proportion of loyalists who lived among them. Watching militia drill at Buckminster’s Tavern, the pair listened, recalled D’Berniere, as “one of their commanders spoke a very eloquent speech … told them they would always conquer if they did not break, and recommended them to charge us coolly, and wait for our fire, and everything would succeed with them … [and] put them in mind of Cape Breton, and all the battles they had gained for his Majesty in the last war, and observed that the Regulars must have been ruined but for them.”

It was shocking for the British commanders to realize that the colonial militia was well organized, included numerous veterans of the French and Indian War, and was firmly loyal to the Patriot movement. Worse than that, the amateur soldiers were confident about challenging the king’s regulars.

On March 30, Gage ordered Brig. Gen. Hugh Percy to take his brigade on a march. Known as Lord Percy, the 32-year-old general was the son of the Earl of Northumberland. A veteran of European campaigns during the Seven Years’ War, Percy was a talented soldier. Politically a Whig, Percy sympathized with the colonists against the Crown’s policies, although he was repelled by the Patriots’ threats of violence.

Percy led 1,000 soldiers into the countryside for several miles, setting off a great deal of commotion. Riders galloped to spread warning of the British march. Locals pulled the planks up from a bridge at Cambridge and brought two cannons to guard the bridge at Watertown. In the end, Percy’s men found no hidden weapons or powder and returned to Boston.

Nonetheless, Percy’s march made the Patriots wary of warlike British forays into the countryside. Pondering the matter, the Provincial Congress decreed that if more than 500 British troops, with artillery and baggage, again marched outside of Boston it would be considered an aggressive threat. In such an event, the militia would be mustered to form an “army of observation.” They could watch the British, but under no circumstance would the provincial troops fire unless fired upon first.

By early April most of the Patriot leaders in Boston had left town to avoid arrest. Most important of the leaders remaining behind was a young physician named Joseph Warren.

Each British foot regiment had two elite flank companies, one of grenadiers and the other of light infantry. On April 15, Gage pulled the flank companies from regular duty. At the same time, naval officers were asked to supply sailors and boats to transport a large force of infantry across the Charles River. Grenadiers and light infantrymen were told to expect instruction in new tactics and maneuvers. In reality, Gage was sending these 700 men to Concord to seize a large supply of gunpowder known to be in Patriot hands.

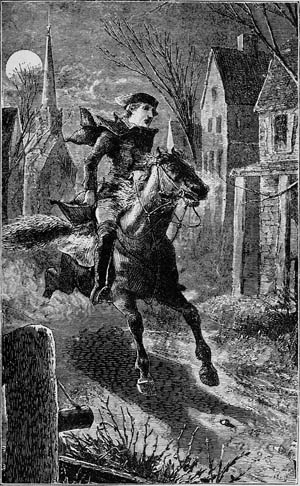

Although no direct word of Gage’s plan leaked out, it seemed obvious to Warren and other Patriots that another out-of-town expedition loomed. The Provincial Congress had just wrapped up a session in Concord, but the Bostonian members were still there or in nearby towns such as Lexington, realizing that they risked arrest if they returned to the city. Boston silversmith, engraver, and political activist Paul Revere was a trusted figure in Patriot circles. Hancock chose him to ride to Lexington and warn John Hancock and Samuel Adams about the potential of a British threat to Concord.

When Revere returned, he stopped in Charlestown. He knew that if the British left Boston, getting word out to the countryside would be difficult. The only land exit at Boston Neck was guarded, and the ferryboats were tied up at night under the eyes of the Royal Navy. Old North Church, with its 191-foot-high steeple, was the city’s tallest structure. Revere told several Patriots in Charlestown to watch for signal lanterns flashing from the steeple. One lantern meant the British were marching by land; two lanterns meant that the redcoats were crossing by boat to the mainland.

On the morning of April 18, Major Edward Mitchell of the 5th Regiment of Foot led a patrol of 20 mounted officers and men into the country. Mitchell scattered his men to guard strategic points along the area’s roads with orders to arrest any messengers trying to warn the Patriots of the British expedition. About half of the patrol headed toward Lexington.

British officers often took pleasure rides into the countryside, but 20 was a lot of horsemen for an innocent jaunt. All the riders were all in full uniform rather than casual off-duty clothing. They asked a lot of questions, especially about the location of Adams and Hancock. Instead of riding for a few hours and then returning to town, they stayed out in the country long after sunset. Mitchell’s party clearly signaled sinister intent to the Patriots.

On the afternoon of April 18, Lt. Col. Francis Smith learned from Gage that he was going to lead the flank companies out of town on a march. Aged 52, Smith had served for more than 30 years in the army without making much of a mark. He had led the 10th Regiment of Foot in Boston for several years. His peers thought him overweight, slow, and plodding, but he was a senior officer of the garrison with a reputation for caution. Gage could be assured that he was not sending a hothead in charge of this potentially volatile mission.

Second in command of Smith’s force was Pitcairn. Scottish-born, Pitcairn generated respect and friendship among the military as well as Boston’s loyalists and Patriots. He was a veteran of Canadian campaigns during the French and Indian War. One of his sons, Midshipman Robert Pitcairn, served in the Royal Navy. In 1767, the young Pitcairn was the first European to see the South Pacific island that bears his name: Pitcairn Island, later known as the home of the mutineers of the HMS Bounty.

Smith set out at about 10 pm on April 18. The navy did not supply enough boats to embark all of the troops at once, and it took about four hours to assemble the force on the west side of the Charles River at Lechmere’s Point. Lieutenant William Sutherland of the 38th Regiment of Foot wrote, “Here we remained for two long hours partly waiting for the rest of the Detachment & for provisions.” When everyone was across, the column marched at 2 am, but “the Tide being in we were up to our middles before we got into the road.”

Sutherland remembered that they saw no one until they had marched about four miles. Then, Lieutenant Jesse Adair of the marines shouted, “Here are 2 fellows galloping express to Alarm the Country.” Riding after them, Sutherland and a guide captured both couriers. Shortly thereafter, Lieutenant William Grant of Mitchell’s scouting party joined them. Grant told them that he was afraid that “the Country … was alarmed,” a fact proved by the sound of numerous gunshots echoing in the distance “between 3 & 4 in the morning.”

Indeed, residents of the farms and villages ahead of the British were well aware of their approach. Gage was so secretive that hardly any of his commanders knew the intent of the upcoming march. Yet, British personnel in town spoke carelessly about the flank companies’ relief from duty, the navy’s preparation of boats to ferry troops, and rumors about an imminent military expedition. Patriots in town knew of the vital supply of powder and the concentration of their political leaders at Concord, so the town seemed an obvious destination for any British operation. Soon afterward hundreds of soldiers stepped into their boats, and the news of the event reached Joseph Warren at his home on Hanover Street.

Technically, Warren was not authorized to raise an alarm and call out the militia; although there were more than 500 soldiers assembled, they did not have artillery with them. But Warren deemed the expedition was enough of an emergency to bend the rules, so he ordered Dawes and Revere to warn their allies in the surrounding countryside to take up arms to resist the British march on Concord.

Revere headed first to warn Adams and Hancock in Lexington. After leaving Warren’s home, he arranged for the lighting of two signal lanterns in the Old North Church belfry. The lanterns burned only a short time, just in case a British soldier or loyalist chose to investigate the unusual lights. With the signal lanterns, the news reached Charlestown even before Revere set out in a rowboat to cross the water.

Stepping out of the boat at about 11 pm, Revere took the road to Lexington, evading British patrollers and shouting and awakening sympathetic households along the route. Dawes took a different route, leaving town by way of Boston Neck.

At 12 am, Revere was at the Lexington home of the Reverend Jonas Clarke, where Hancock and Adams were staying. Pounding on the door, Revere was met by William Monroe, sergeant of a militia detachment guarding the delegates. Monroe admonished Revere about disturbing the household with so much noise. “Noise?” said Revere. “You’ll have noise enough before long—the regulars are coming out!”

Dawes caught up with Revere in Lexington. The two riders headed together down the road toward Concord. Joining them was Dr. Samuel Prescott. Although sympathetic to the Patriot cause, Prescott was there only because he was returning home after a courting visit to his sweetheart.

Revere’s party was far ahead of the British force, which was still gathering at Lechmere Point; however, Mitchell and some of his men lurked in the area and confronted them at 1 am. Revere was captured, but Dawes and Prescott managed to escape. Prescott rode, broadcasting his warnings, on to Concord.

Back in Lexington, 130 militiamen assembled on the green, or town common. In command, Parker ordered the men to load their muskets and drilled them for a time. With the night being chilly and the regulars some distance away, Parker dismissed his company, telling them to return when they heard the beating of a drum. Many of the men remained close by, retiring into homes overlooking the green or inside Buckman’s Tavern.

New riders took the alarm to other towns and villages in all directions far beyond the Concord Road. Church and town bells tolled, as they did for all emergencies. Militiamen pounded drums and fired musket shots to awaken and alert the population. Bonfires glowed from hilltops, sending warnings far away into the night.

With couriers, tolling bells, and signal shots buzzing around them, Smith sent back to Boston for reinforcements. Gage already sent orders at 4 am for Percy to lead another force to aid Smith; however, two mishaps delayed the dispatch of help. First, Gage’s orders went to the quarters of a brigade major who was not home. A servant placed the papers on a table but neglected to inform the major when he returned. No one realized the mistake until Smith’s urgent appeal reached Boston an hour later. Then, the infantry assembled but expected the arrival of several hundred marines. After another long delay, inquiries determined that orders to dispatch the marines had been sent to Pitcairn, who of course was already gone. Five hours slipped by before Percy left Boston.

Approaching Lexington before 5 am, Sutherland and Adair rode ahead of the main force with a sergeant and a half dozen men. Gunshots popped in the dark, but the advance men relaxed slightly, concluding that the shots were just fired in alarm and not directed at them.

Several horsemen appeared in the road. Most of the strangers quickly rode away, but one of them turned toward the British and aimed his musket. He pulled the trigger, and Sutherland saw the flare of gunpowder from the priming pan. But the weapon misfired, and the horseman rode away with his empty musket. Misfire or not, that flash in the pan proved that the locals would shoot at British troops. Pitcairn halted, ordered his light companies to load, and then pressed on to Lexington.

About 11 miles from Boston, the road from Boston split around Lexington Green, the town common. The road’s left fork ran to Concord; the right, to Bedford. A short lane linking the Bedford and Concord Roads formed a top to the triangle-shaped common, about 100 yards across and covering two and a half acres. Like other American town commons, it was a publicly owned grazing ground for sheep and cattle, so the ground was mostly open and covered by closely cropped grass. At the bottom of the triangle at the fork of the road was a meeting house, something of a combination church building and town hall. Nearby was a separate belfry tower, on the northwest corner of the green stood a schoolhouse, and across the Concord Road was Buckman’s Tavern.

Alerted to the redcoats’ approach, a drummer pounded an alarm at 5 am. Reassembled, the militiamen lined up with Parker near the north end of the green. Spectators watched from the edge of the green, from their homes, or other sheltered spots. One onlooker, Elijah Sanderson, did not have a musket but lingered to see what would happen. John Lowell, Revere and Hancock’s secretary, passed behind Parker’s line carrying a heavy trunk packed with secret papers out of harm’s way. Parker steadied his men, telling them, “Stand your ground. Don’t fire unless fired upon. But if they want to have a war let it begin here.”

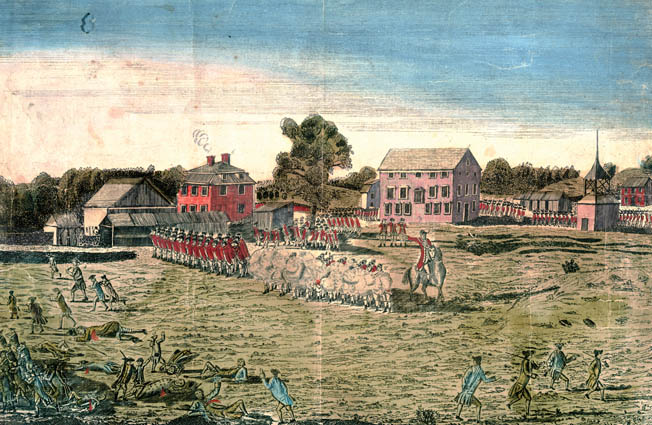

It was not full daylight yet, but when Pitcairn got as far as the meeting house, he could see the Patriot force standing on the common. Adair led part of the British force around the right of the meeting house. Pitcairn moved with the remainder around the left of the building. Altogether, the British on the scene numbered 250, with several hundred more not far behind.

No one had a clear view of the whole setting of the Battle of Lexington. First-hand memories of the next few moments of this landmark event in American history were remembered as a kaleidoscopic jumble of conflicting impressions.

Pitcairn and more than one other of the mounted officers rode ahead of the redcoats, shouting at the militia to throw down their muskets and get out of the way. One of the officers was heard to order, “Throw down your arms, ye villains, ye rebels!”

Parker, of course, saw that he was heavily outnumbered. Patriot sources later identified 77 men assembled on Lexington Green. It is unclear why Parker seemingly considered making a stand on the green. Stricken with tuberculosis, he had only a few months to live and left only brief statements regarding the Battle of Lexington. Like other officers, Parker had instructions not to let his men fire unless fired upon. Strategists among the provincial and Continental Congress wanted to cast the British as wrongful in the event of a serious armed clash.

For that reason, Parker ordered his men to disperse. Many of his men turned around and walked away. Others remained in line, whether from stubbornness or because they did not hear the order.

From somewhere, a musket boomed. No one could say for sure who fired it. Quite possibly it came from a militiaman shooting from behind a stone wall or a building overlooking the green. Nearly all of the Lexington Patriots claimed that the British fired first. John Robins testified that he heard a mounted British officer order, “Fire, by God, fire!” and numerous other witnesses stated they heard similar orders.

Revere, still moving away with Hancock’s papers, heard two distinct shots that quickly gave way to “a continual roar of musketry.” Firing from the redcoats intensified, and the troops disappeared into a heavy cloud of powder smoke that hid everyone except the mounted officers.

Chroniclers sympathetic to the Patriots identified Pitcairn as the angry officer ordering his men to fire without provocation. Pitcairn’s face was not well known in Lexington, though, and the dim light would have made it hard to distinguish one mounted British officer from another. The major’s marine uniform would have been similar to those of the army officers. British witnesses who knew Pitcairn stated that he rode his horse back toward his men, ordering them not to fire. Early in the fighting, two bullets struck the major’s horse.

It is possible that some of the first men to fire did so reluctantly and shot over the heads of their opponents. At first the British gunfire had so little impact that it seemed that the redcoats were not using live ammunition. Sanderson saw a mounted officer fire a pistol. He then saw more of the regulars firing. “I looked and seeing nobody fall thought … they couldn’t be firing balls, and I did not move off,” wrote Sanderson.

Most of the militia fled, but part of Parker’s company held on and returned fire. One man, John Munroe, so heavily charged his firelock that when he pulled the trigger the explosion blasted off a one-foot-long piece of his musket barrel.

Solomon Brown took up a position behind a stone wall and shot back at the redcoats. Sanderson saw the British troops firing at the wall that was sheltering Brown. “I saw the wall smoke with the bullets hitting it,” wrote Sanderson. The two men ran to a safer position.

British officers kept shouting for their men to cease fire. Defying their orders, many of the soldiers kept firing, and others charged with their bayonets. His sword swinging, Pitcairn hacked down several musket barrels to prevent their loads from striking more colonists.

Whether they stood their ground or obeyed demands to leave the field, Parker’s men risked being shot or run through. Fatally wounded, Jonathan Harrington dragged himself to his home by the green. He died on his doorstep in front of his family. Jonas Parker, the militia captain’s cousin, placed his hat on the ground and into it tossed his flints and bullets. Parker was shot through the body, fell to his knees, and tried to reload. Before he could fire one more time, a soldier killed him with a bayonet thrust. John Tidd survived being struck in the head by a cutlass, which knocked him unconscious.

Smith soon reached the battleground. Aghast at his soldiers’ loss of discipline, Smith ordered a drum roll to summon the men back into their ranks. By the time the officers regained control, the militia was driven from the green. Eight Lexington men had been shot dead and 10 more wounded. The British were almost unscathed; Pitcairn’s horse and one or two wounded soldiers were the only casualties.

It was only after the unintended battle that Smith revealed to everyone that they were going to Concord. A few officers suggested turning back, but Smith brushed off their objections. Leaving behind the blood-spattered common and the stunned families of the dead, the regulars shouted three cheers and fired a musket salute.

The redcoats pressed on, marching into Concord at about 7 am. Local militia gathered to resist the regulars, but they were not yet ready for battle. Steadily falling back, the locals finally withdrew from town and retreated across the Concord River by way of the North Bridge. Colonel James Barrett, the highest ranking officer present, halted them at Punkatasset Hill.

Smith sent Captain Walter Laurie with 115 men to guard the North Bridge while the rest of the British seized military supplies. In Concord, the soldiers smashed open 60 casks of flour, broke the trunnions off of three 24-pounder cannon barrels, and tossed some cannon balls into a millpond. Then the troops burned some captured carriage wheels and several barrels of wooden spoons and trenchers. After chopping down the town’s liberty pole, the regulars set the courthouse on fire.

Punkatasset Hill was about 11/2 miles from the center of Concord. For some time, the militia watched the regulars at the bridge but made no move against them, preferring to wait for more men to arrive from nearby villages. With a large and growing force of hostile militia gathering across the river, Laurie sent for help, but Smith did not respond.

At 9 am, the militia force had grown to about 450 men from half a dozen towns. Smoke rising from the burning supplies was plainly visible to everyone on Punkatasset Hill. It appeared that the British were burning the town. Barrett ordered Major John Buttrick to take the militia to the bridge and cross over but not to fire unless fired upon.

When the enemy approached, Laurie withdrew across the river and ordered his men to pull up the bridge’s floor planks. After some warning shots, Laurie’s troops fired into the Massachusetts men, killing Captain Isaac Davis and a fifer named Abner Hosmer. Buttrick’s men retaliated with deadly precision. Four redcoats were killed and nine were wounded. Among the wounded were half of Laurie’s eight officers. Heavily outnumbered, the British soldiers broke and ran from the bridge toward Concord.

A wounded British soldier, left behind, was savagely chopped to death with a hatchet by one of the New Englanders. News of the barbaric incident spread through the British ranks, quickly twisting into a rumor that the Massachusetts men scalped every dead or wounded regular.

Crossing the bridge, the militia settled behind a stone wall. Laurie’s troops rallied, and Smith and more troops joined them. For the rest of the morning, the two sides faced each other but fired no shots. Some of the militiamen slipped away to Meriam’s Corner, a likely spot for an ambush on the road the British had to take east of Concord.

At noon, Smith ordered a withdrawal to Boston. On the road marched the grenadiers and the wounded. Light infantry shadowed them, prowling a ridge north of the road to clear potential attackers out of the way.

The first mile of the retreat from Concord was strangely quiet. No fifes or drums played, and no shots rang out as the British tramped along the road. At Meriam’s Corner, a bridge crossed a creek that also cut the ridge, forcing the flankers down into the main roadway.

Since early morning, word of Smith’s expedition had spread far and wide. Smith’s lingering stay at Concord was a costly mistake. From villages 15 or 20 miles away, volunteers brought their muskets to join the men waiting in ambush at Meriam’s Corner. When the British reached that point about 12:30 pm and the terrain funneled all of them together on the road, more than 1,000 New Englanders confronted them. A British volley, fired too high, had little effect on the rebels. Return fire killed two redcoats and wounded several more.

After Meriam’s Corner, the British were under constant attack. The road from Concord dipped into little valleys and ravines, well suited for ambushes. Everywhere, it seemed, hills, trees, buildings, and stone walls offered countless firing positions.

At 2 pm, just outside Lexington, Parker and the survivors of the skirmish on the town green lay in wait. Some of the men wore bandages stained by wounds suffered early that morning. From their position on a hill, their muskets commanded a curve in the road. In what became known as “Parker’s Revenge,” the militia repaid the British for their callous cheering as they marched out of Lexington a few hours before. Smith was shot in the leg, and several soldiers were killed or wounded.

All day the militia took special aim at the British officers and inflicted high casualties among them. Officers’ uniforms were easy to pick out amid a mass of soldiers. Gold or silver lace, rather than simpler woolen lace, adorned officers’ coats. Further tagging officers were their gorgets, which were the highly polished, crescent-shaped, ornamental silver plates hanging from their necks.

Even the color of his coat could earn an officer a bullet. Officers wore scarlet coats, which were colored with cochineal, a costly dye made from insects native to Central and South America. Cochineal yielded a scarlet red that held its vivid color for a long time. Enlisted men, on the other hand, wore red coats tinted with madder, a vegetable dye. With exposure to the elements, madder soon faded from red to pale shades of brownish or orangey pink.

Before reaching Lexington, the British met another ambush at Fiske Hill. Pitcairn was thrown from his horse. By this time, the column was in serious danger. They were slowed by having to carry dozens of wounded. Ammunition was running low. Anyone who looked back saw the road dotted with his dead comrades. More and more of the officers were falling dead or seriously wounded. Panic drove many soldiers to run away. With nowhere to go, they made for Lexington Green.

At Lexington, the fleeing troops found better salvation than they dared hope. Percy was just east of the village with more than 1,100 men and two 6-pounders. As Smith’s demoralized troops ran for safety in a hollow square formed by fresh infantry, Percy’s gunners opened fire on the meeting house and nearby buildings. Cannon balls punched through the walls, driving any potential ambushers outside.

Although the participants were only truly aware of the fact much later, the shootings at Lexington Green galvanized the disparate town militias into a single revolutionary army. There was as yet no official leader. Men acted on their own accord, or with their local officers, but overall the battle along the Concord Road was handled well enough by the insurgents.

Commissioned a brigadier general by Massachusetts in 1774, William Heath was the top-ranking Patriot officer present that day. Heath saw only a limited portion of the battle. Warren, who left Boston that morning, joined Heath on the road. They reached Lexington around 2 pm, about the time that Percy’s guns had halted the momentum of the Patriots. Heath steadied the men after the British cannon balls had scattered them

With their forces united, Percy and Smith started again for Boston. Soldiers took out their anger by looting or burning houses along the way. Patriots hounded the British and heavy fighting continued for miles along the road. Mackenzie noted, “Our men had very few opportunities of getting good shots at the Rebels, as they hardly ever fired but from under cover of a Stone wall, from behind a tree, or out of a house; and the moment they fired they lay down out of sight until they had reloaded.”

Redcoat casualties mounted, but the battle was not a one-sided affair. Light infantrymen, well trained in skirmishing warfare, stalked isolated pockets of Patriots.

Waiting in ambush for the British, a few militiamen hid behind some barrels at a place called Watson’s Corner. Their attention riveted on the road, they didn’t see a band of light infantry slipping up on them. The soldiers stabbed three would-be ambushers with their bayonets. Among the dead was Major Isaac Gardner, the highest ranking officer of either side to die that day.

Fighting on April 19 began in the dim light of dawn, and by the time it ended musket flashes blazed brightly in the gloom of dusk. Percy opted to return to Charlestown rather than taking the longer route to Boston Neck. By 9 pm, the British were safe on Charlestown’s peninsula. There were approximately 4,000 Patriots in pursuit by then, but the soldiers held a strong and easily defended position on high ground. Later, that choice of a safe place would seem ironic: it was Bunker Hill.

In their shocking and unexpected defeat of April 19, British losses reached 73 officers and men dead, with 200 wounded or missing. Patriot losses were much lower, estimated at 49 dead, 39 wounded, and five missing.

Enough rebels poured in to form an army that put Boston under siege the next day. At the most intense clash of the siege, the June 17, 1775, Battle of Bunker Hill, the British won a hard-fought but costly victory to drive patriot forces away from commanding heights in Charlestown. The Continental Congress found a leader who pulled together the disorganized Patriot forces: a Virginian named George Washington. Boston’s siege went on into the next spring. Washington and his army would fight many battles, but there was no Battle of Boston. Under orders from London, the British evacuated the city on March 17, 1776.

American militiamen, mostly amateur soldiers without professional military training, performed with great success on April 19, 1775. Their brave but doomed defiance at Lexington, their determined and successful stand at Concord, and the staggering defeat they dealt to a large army of regulars have ever since echoed down through American history. Revolutionary Patriots gained the confidence they needed to see them through to the end a war with a major European power. After all, the fighting on April 19 proved that the Patriots could make Britain’s professionally trained officers and regulars flee in panic.

Perhaps the lessons of Lexington and Concord were learned too well. For decades, Americans felt secure under the protection of their militia. But the early United States also learned a longtime contempt for professional troops, hindering development of a permanent, trained army with a corps of experienced officers. In situations where trained regulars might have survived and won, thousands of poorly trained and incompetently led militiamen would die in early Indian wars or the War of 1812. Even during the Revolution, the final victory at Yorktown required regiments of American regulars and French allies who could stand and exchange volleys with rows of redcoats.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments