By Al Hemingway

Whenever the name of Benedict Arnold is mentioned, people immediately think in terms of the traitorous act he attempted to perpetrate against the fledging United States of America in 1780 by surrendering West Point, New York, to the British. There was, however, another side to Arnold. Just four years earlier, the brash, newly commissioned general in George Washington’s Continental Army captured Fort Ticonderoga, nearly seized the Canadian city of Quebec, and saved the day at the Battle of Saratoga, almost losing a leg in the process.

Award-winning author James L. Nelson closely examines Arnold’s early role in the American Revolution in his new book Benedict Arnold’s Navy: The Ragtag Fleet That Lost the Battle of Lake Champlain but Won the American Revolution (McGraw-Hill, New York, 2006, 386 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover).

Award-winning author James L. Nelson closely examines Arnold’s early role in the American Revolution in his new book Benedict Arnold’s Navy: The Ragtag Fleet That Lost the Battle of Lake Champlain but Won the American Revolution (McGraw-Hill, New York, 2006, 386 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover).

From the outset of the conflict, the ambitious Arnold saw the importance of Lake Champlain and the occupation of Canada as paramount to the patriot cause. In the early days of the uprising, there was no real federal authority for acquiring men and supplies. Each state went in different directions to procure these important items. Convincing the Massachusetts legislature that guns and ammunition could be had by seizing Fort Ticonderoga, Arnold quickly received the authority to raise a force to accomplish this mission.

While traveling to upstate New York to capture the fortification, Arnold happened upon the famed Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys. The motley crew of Vermonters agreed to join in, but only if Allen remained in command. Arnold acquiesced, much to his dismay, and soon learned to intensely dislike Allen and his band of hard-drinking ruffians. When the fort was later seized, Allen purposely neglected to mention Arnold in his report. This act cemented Arnold’s hatred of Allen and his men.

Arnold led a force to lay siege to Quebec. His bold plan might well have worked, had it not been for the long, arduous trek his small army was forced to make during the winter months. Also, one of his best officers, Richard Montgomery, was killed when assaulting an enemy blockhouse. With Montgomery’s untimely death, the attack fizzled and a golden opportunity was lost.

Arnold’s greatest achievement was still to come. The British also realized the vast military importance of Lake Champlain. If they could move down the lake and take Albany, they could march into New York City and join forces with General Sir William Howe’s army. The Continental Army would, in effect, be cut off and soundly defeated.

The British, however, did not realize that Arnold had foreseen just such a move and begun building a ragtag fleet to meet the greatest navy in the world. Arnold knew that he could not defeat such a powerful armada, but if he could inflict enough damage and slow the British down, they would have to wait until the following spring to put their plan into action. Arnold was buying valuable time for George Washington’s army, which was in the process of being routed in New York.

Nelson does a masterful job of storytelling, describing not only the military actions but also the petty jealousies and backbiting that were all too common in the Continental Army at the time. Arnold spent two years in the field before returning from New York and Canada, and was not privy to the political shenanigans occurring within the Continental Congress and Washington’s officer corps. Not politically attuned, he became bitter and disillusioned about his role in the newly forming country and decided to turn his back on all he had fought for.

Still, as Nelson states, “Benedict Arnold was responsible for the victory at Saratoga, as much as any one man could be. That honor is due him not just because of his leadership … but because he had set the stage for the battle itself. The defeat of John Burgoyne’s army, the first great victory in the American Revolution, had its origins in the valiant, doomed stand made in a forgotten corner of a wilderness lake by Benedict Arnold’s navy.”

The Bonus Army: An American Epic by Paul Dickson and Thomas B. Allen, Walker and Co., New York, 2005, 370 pp.., illustrations, notes, index.

The Bonus Army: An American Epic by Paul Dickson and Thomas B. Allen, Walker and Co., New York, 2005, 370 pp.., illustrations, notes, index.

John Henry Bartlett, former governor of New Hampshire and postmaster general of the United States, saw “a force of Cavalry with sabers glistening, making the ominous click of iron feet on the pavement, which sounded so much like war.” This was not the memory of a veteran of any foreign conflict, but rather the firsthand observation of an individual witnessing American troops preparing themselves to attack other Americans—World War I veterans who had arrived in Washington, D.C., to demand the bonus promised to them by the government.

Authors Paul Dickson and Thomas B. Allen have done a marvelous job in researching and telling one of the most embarrassing and forgotten moments in American history. Veterans who had fought in the Great War had been guaranteed a bonus for their service. The stipend, however, was not payable until 1945. With the country wallowing in the Great Depression, many of these men were unemployed and wanted their cash then and there.

By the summer of 1932, thousands had descended on the nation’s capital and established makeshift camps, pejoratively dubbed “Hoovervilles” after President Herbert Hoover, to peacefully petition Congress for their money. On July 28, 1932, frightened by erroneous reports that the crowd of veterans was composed mainly of Communist sympathizers, Hoover unleashed the Army to drive the veterans out of their encampments. Donning their old uniforms, Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur, and future Generals Dwight D. Eisenhower and George S. Patton, led the troops into the streets.

The forced eviction soon turned into a melee. Several protestors were killed, along with a few policemen. Soldiers indiscriminately tossed tear gas canisters and, as a result, several children died. The government would later claim these unwarranted and unnecessary deaths were the result of “intestinal disorders.”

In the end, the Bonus Army’s march of 1932 paved the way for future marches on Washington by Americans wanting to question their government’s actions on various issues. On June 12, 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the GI Bill of Rights into law. Returning veterans from World War II now had the opportunity to procure low-cost loans, attend college, and purchase homes. Almost eight million veterans took advantage of this landmark legislation. They owe an extreme debt of gratitude to their predecessors, the veterans of the Bonus Army, without whose actions there would have been no GI Bill.

B-17 at War by Bill Yenne, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2006, 128 pp., photos.

B-17 at War by Bill Yenne, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2006, 128 pp., photos.

The B-17, or Flying Fortress, is arguably one of the greatest bombers ever to fly during wartime. The aircraft could take extensive flak damage, arrive on target to deliver its bomb load, and still have enough spunk to return to base. Nearly 13,000 B-17s were manufactured during World War II. The aircraft was so popular that the British Royal Air Force used them as well. Even the Germans admired the well-built bomber. In fact, some 40 downed Flying Fortresses were repaired by the Nazis, repainted with German unit insignia, and flown again.

Accompanying the text are over 100 photographs depicting the B-17 in action, together with the crews and pilots who flew them in combat. By war’s end, an incredible 640,000 tons of explosives were dropped over occupied Europe and German industrial centers, railroads, and supply depots. According to the author, this was “roughly half of the overall total dropped by American bombers of all types.” The B-17 was indeed an outstanding workhorse for the United States and helped achieve victory in World War II.

Battle Line: The United States Navy, 1919-1939 by Thomas C. Hone and Trent Hone, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2006, 244 pp., illustrations, notes, index.

Battle Line: The United States Navy, 1919-1939 by Thomas C. Hone and Trent Hone, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2006, 244 pp., illustrations, notes, index.

The period between the world wars was a difficult time for the U.S. Navy. Despite this tumultuous period, however, the seagoing branch of the American military developed faster and more powerful battleships, destroyers, and cruisers. The Navy also pioneered aviation and enlarged its carrier force. In addition, it foresaw the advantages of the submarine and began to build that arm of the fleet as well.

All of this new technology was accomplished with limited funds, a small force of officers and sailors, and a shrinking fleet that had been mandated by treaties. Also, the public had the mistaken idea that a smaller navy was all that was needed to protect American interests at home and abroad. Authors Thomas and Trent Hone, a father and son writing team, have done an in-depth study of that changing period in the Navy’s history. They have also uncovered never-before-published photographs of the ships of the line during those years.

The transformation from a peacetime navy to a wartime one came none too soon with America’s entry into World War II. “They and their ‘treaty fleet’ did just what was expected of it in 1941 and 1942 and then,” write the authors, “augmented by a tidal wave of weapons created and produced by the world’s most powerful economy, fought to victory in the greatest naval war in human history.”

Beyond Shock and Awe: Warfare in the 21st Century, edited by Eric L. Haney with Brian M. Thomsen, Berkley Publishing Group, New York, 2006, 258 pp.

Beyond Shock and Awe: Warfare in the 21st Century, edited by Eric L. Haney with Brian M. Thomsen, Berkley Publishing Group, New York, 2006, 258 pp.

Beyond Shock and Awe is a compilation of articles written by retired military men, historians, and experts in their fields. Each chapter touches on weapons, strategy, and scenarios for future warfare in this century.

The authors contend that the “World War II method” of warfare has become outdated. The reasons are cultural, they say, a combination of “political reality” and “technical capability” that renders that style of fighting obsolete. “America is now in a position analogous to that of the British Empire in the last quarter of the nineteenth century,” they write. “We will find ourselves fighting the brush wars of the world, engaging relatively primitive opponents with a combination of superior tools and a superior warrior force.”

The book offers a fascinating glimpse of what the future may hold for America’s military, and the types of conflicts we could become embroiled in around the globe.

Broadcasts from the Blitz: How Edward R. Murrow Helped Lead America into War by Philip Seib, Potomac Books, Dulles, VA, 2006, 209 pp., photos.

Broadcasts from the Blitz: How Edward R. Murrow Helped Lead America into War by Philip Seib, Potomac Books, Dulles, VA, 2006, 209 pp., photos.

“This is London …”

That is how Edward R. Murrow would open his broadcasts for CBS radio during his tenure in England from 1939 until 1941. Murrow was there when England declared war on Germany, and he also covered the infamous blitz by Adolf Hitler’s relentless Luftwaffe. Every night, the American people listened intently as Murrow painted a “haunting image” of bombed-out buildings, jam-packed underground subways serving as bomb shelters, and the hundreds of civilian casualties Great Britain incurred at the hands of the Nazi war machine.

Murrow formed an unofficial alliance with Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Franklin D. Roosevelt to cover the war using his graphic descriptions of the London bombings to persuade the American people to pay attention and take notice. He realized the evil intentions of the Nazis early on, and used his journalistic talents to wake up the United States and warn the American people that they might be next in Hitler’s vision of world conquest.

Was this proper journalism? Author Philip Seib thinks it was. He is convinced that Murrow committed no “ethical transgression.” Rather, the young journalist was correct to illustrate the evils of the totalitarian regime in Germany. He “served his country well,” according to Seib.

In Hostile Skies: An American B-24 Pilot in World War II by James M. Davis and edited by David L. Snead, University of North Texas Press, 2006, 226 pp., illustrations, index.

In Hostile Skies: An American B-24 Pilot in World War II by James M. Davis and edited by David L. Snead, University of North Texas Press, 2006, 226 pp., illustrations, index.

Whenever a rare memoir is uncovered, especially one that is insightful and poignant, historians are ecstatic. Such was the case with James Davis, a B-24 bomber pilot in World War II, who took the time to gather his thoughts and put them to paper. The manuscript found its way to David Snead, an assistant professor of history at Texas Tech University. The result is a wonderful book that has captured the essence of flying the B-24 Liberator in World War II on numerous bombing missions over Germany.

Thanks to Davis, the reader can fully understand the grueling training program that he and others had to successfully complete before being awarded their aviator wings. Davis subsequently flew in some of the most dangerous assignments in support of Operations Cobra and Market Garden. He flew raids over some 20 enemy cities and destroyed numerous supply depots, factories, and oil refineries. Davis gives his account a personal touch when he describes the wife he left behind to enter the service and fight for his country.

He summed up his wartime service when he wrote, “From the time I saw my first airplane I had a burning desire to fly but did not have enough hope that it would ever happen. However, while the war brought many unspeakable horrors, it provided me with new adventures, challenges, and opportunities.”

John Paul Jones: America’s First Sea Warrior by Joseph Callo, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2006, 250 pp., maps, illustrations.

John Paul Jones: America’s First Sea Warrior by Joseph Callo, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2006, 250 pp., maps, illustrations.

John Paul Jones has been called “the father of the American navy.” Although this term may oversimplify the man, there can be no doubt of Jones’s bravery and coolness under fire.

Born in Scotland, which undoubtedly had something to do with his rebellious nature, Jones took to the sea at a young age. His early years aboard British vessels forged his ability to command ships and men. When the American Revolution broke out, Jones immersed himself in the conflict. To him, liberty was essential.

In February 1779, Jones took command of the Duc de Duras and promptly renamed her the Bonhomme Richard. By the summer, along with two small frigates, a corvette, and a cutter, he sailed off the western coast of Ireland, the northern coast of Scotland, and down to the eastern shore of Scotland, seizing British merchant ships at will.

Vilified in the English press, Jones did not see these acts as those of a common pirate. To him it was revenge, pure and simple, for British atrocities perpetrated on the colonists. Also, the author points out that Jones never profited from these raids. Jones noted that he easily could have become a privateer rather than serving in the Continental Navy, where the pay was substantially less.

Although difficult to get along with, Jones’s ability as a naval officer was without question. His extraordinary accomplishments against a superior force gave the American people, starving for any news of victories on land or sea, a glimmer of hope that victory was possible.

Jones’s remains were returned to the United States in April 1906. It was then, 114 years after his death, that Jones received perhaps his most fitting accolade when he was called “that man who gave our Navy its earliest traditions of heroism and victory.”

Jose Maria De Jesus Carvajal: The Life and Times of a Mexican Revolutionary by Joseph E. Chance, Trinity University Press, San Antonio, 283 pp., notes, index.

Jose Maria De Jesus Carvajal: The Life and Times of a Mexican Revolutionary by Joseph E. Chance, Trinity University Press, San Antonio, 283 pp., notes, index.

Many once-noted figures in history are forgotten, and little is known of their exploits and accomplishments. The fiery Mexican revolutionary Jose Maria De Jesus Carvajal was one such man. He wanted to go down in history and be remembered as “the George Washington of northern Mexico.”

Born in San Antonio in 1809, Carvajal became interested in politics and supported the liberal cause. In 1835 he was a member of the legislature that vehemently opposed the totalitarian rule of Santa Anna. When Santa Anna’s troops stopped the legislative body from meeting “at the point of a bayonet,” Carvajal fled to Texas. There, he was chosen as a delegate to help write the Texas Declaration of Independence, but was notably absent when the convention was in session. Oddly enough, he chose to remain neutral throughout the fighting in 1836 and was branded a traitor and once again forced to leave his home. He eventually found his way to Louisiana.

For the remainder of his life, Carvajal fought tyranny in Mexico. He raised several armies under Benito Juarez and suffered numerous setbacks. He even traveled to the United States to raise funds for the Juarez government, receiving weapons that would aid in the defeat of the French occupation forces in Mexico.

On August 19, 1874, Carvajal passed away. Author Joseph E. Chance praises Carvajal as “a distinguished Texan and a ‘true Mexican,’ who spent his life in the defense of the Liberal ideals that moved Mexico from a Spanish monarchy toward an independent state ruled by the principles of representative government.”

Masters of the Art: A Fighting Marine’s Memoir of Vietnam by Ronald E. Winter, Presidio Press, New York, 2005, 308 pp., illustrations.

Masters of the Art: A Fighting Marine’s Memoir of Vietnam by Ronald E. Winter, Presidio Press, New York, 2005, 308 pp., illustrations.

No sweeter sound could be heard by an infantryman in Vietnam than the unmistakable whomp of helicopter blades as they arrived to drop off supplies or ferry troops to and from the battlefield.

Former Marine Ron Winter gives an inspiring and gripping account of his time with one helicopter squadron in Vietnam, Helicopter Marine Medium (HMM)-161 known as the “Pineapples.” Winter was a door gunner aboard the CH-46 Sea Knight chopper, one of the workhorses for the Marine Corps during that long and bitter war. He takes us from his enlistment, through boot camp, and, finally, to his unit preparing to deploy to Vietnam in 1968.

While in Vietnam, HMM-161 participated in some of the bloodiest and toughest operations of the conflict in support of the infantry. The missions resulted in the loss of Winter’s fellow crew members, men he would never forget. He himself amassed an impressive record flying 300 combat missions with the Pineapples.

This book is a tribute not only to the casualties of HMM-161, but also to all those crewmen of other squadrons who paid the supreme price during the Vietnam War. Winter summarizes his service: “I tell my children that for a brief time in my life I walked with heroes and giants, was privileged to be included in their company, and to be called ‘Marine,’ using the highest definition of that word. I saw humanity in its most noble form in the most inhumane of circumstances, and I will always remember the strength, the courage, and the sacrifices I witnessed.”

Military Necessity: Civil-Military Relations in the Confederacy by Paul D. Escott, Praeger, Westport, CT, 2006, 215 pp., photos.

Military Necessity: Civil-Military Relations in the Confederacy by Paul D. Escott, Praeger, Westport, CT, 2006, 215 pp., photos.

The United States has always tried to maintain a balance between military and civilian leaders throughout its 230-year history. People’s civil liberties are always paramount, as our forefathers demonstrated when they wrote the Constitution ensuring that these rights could not be forcibly seized by any branch of the government.

There have been times, however, when extreme measures have been put into practice that have endangered this delicate balance. One such period was the Civil War. Both North and South exercised drastic methods to maintain order, often at the expense of an individual’s rights.

Paul Escott closely examines the strained relations in the Confederacy during this tumultuous era. It is ironic that a newly formed country so insistent upon state’s rights at times totally ignored the civil rights of its own citizens. As the South’s predicament worsened and dreams of victory dimmed, “the plea of military necessity” appeared tempting, says Escott. “Citizen’s rights were soon dispensable as military leaders began “seizing resources, conducting dragnets over the countryside, and influencing policy in ways never before imagined. The story of civil-military relations in the Confederacy is an important and instructive tale. In many ways it is also a profoundly unsettling one.”

SAS Zero Hour: The Secret Origins of the Special Air Service by Tim Jones, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2006, 239 pp., photos, notes, index.

SAS Zero Hour: The Secret Origins of the Special Air Service by Tim Jones, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2006, 239 pp., photos, notes, index.

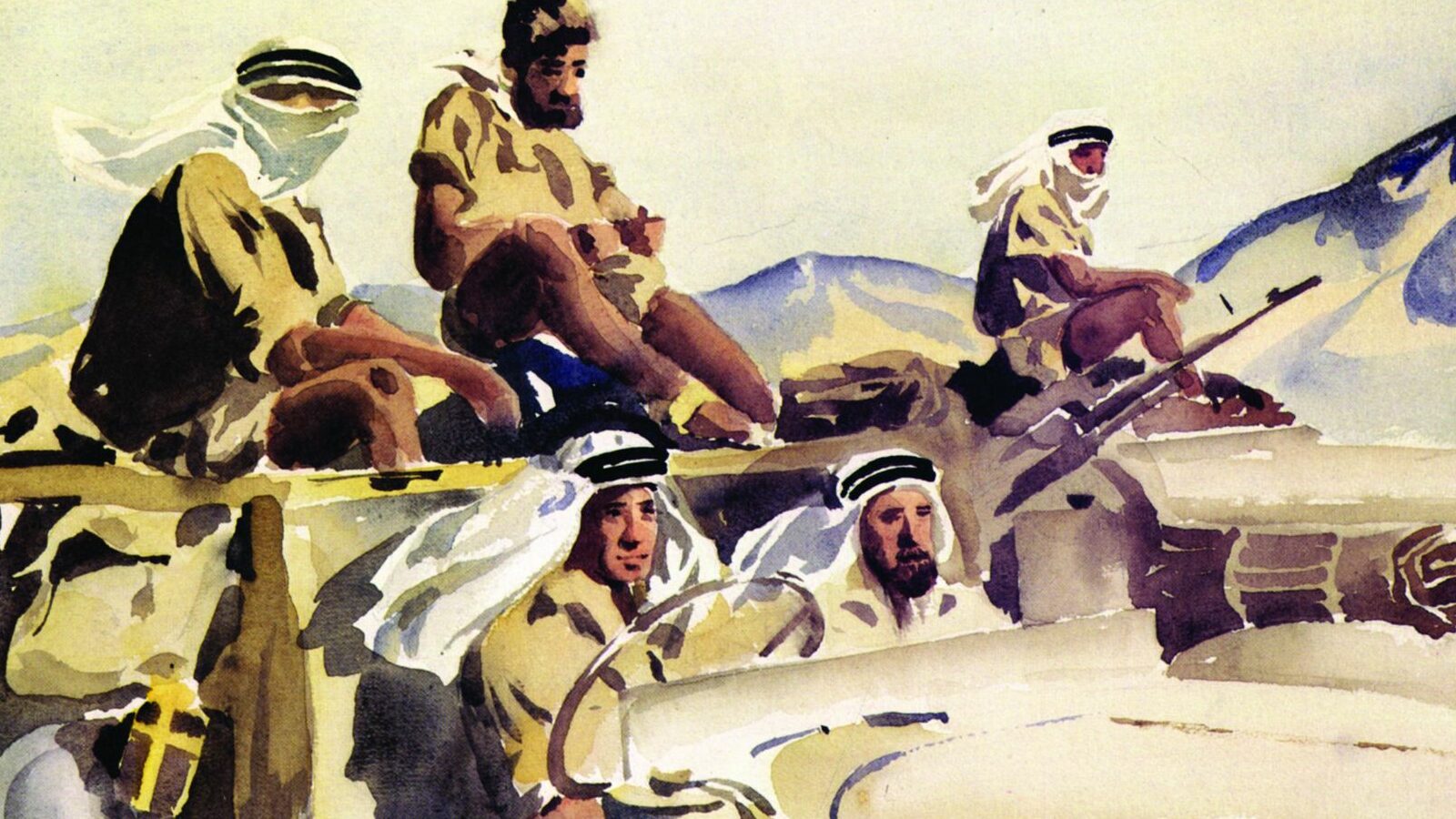

It has long been the contention that Major David Stirling, while convalescing from a parachute jump in North Africa in 1941, had a brainstorm that eventually became the Special Air Service (SAS), Britain’s foremost Special Forces unit. However, author Tim Jones suggests otherwise in his new offering. He believes that other individuals played an important role in forging and giving direction to the fledgling unit, people such as Dudley Clarke. Clarke had assisted in establishing the Commandos, was an expert on guerrilla wars, the Arab campaign in World War I, and the struggle in Palestine.

There is little doubt that Clarke gave Stirling valuable information and assistance. Stirling may have even enlisted Orde Wingate, who served in Palestine and led a guerrilla force called the Chindits in Burma, to gather knowledge from him. Also, General Archie Wavell, who was the “driving force” in organizing a Middle Eastern paratrooper unit, which eventually evolved into Stirling’s SAS outfit.

SAS Zero Hour is compelling reading for those fascinated with this highly secretive British unit.

Warriors Seven: Seven American Commanders, Seven Wars, and the Irony of Battle by Barney Sneiderman, Savas Beatie, LLC, New York, 2006, 285 pp., maps, illustrations, photos, index.

Warriors Seven: Seven American Commanders, Seven Wars, and the Irony of Battle by Barney Sneiderman, Savas Beatie, LLC, New York, 2006, 285 pp., maps, illustrations, photos, index.

“This is a book written for history buffs by one of their own,” writes author Barney Sneiderman. He has chosen seven military leaders he feels shaped American military history by their stunning victories in battles “marked by irony or a twist of fate.”

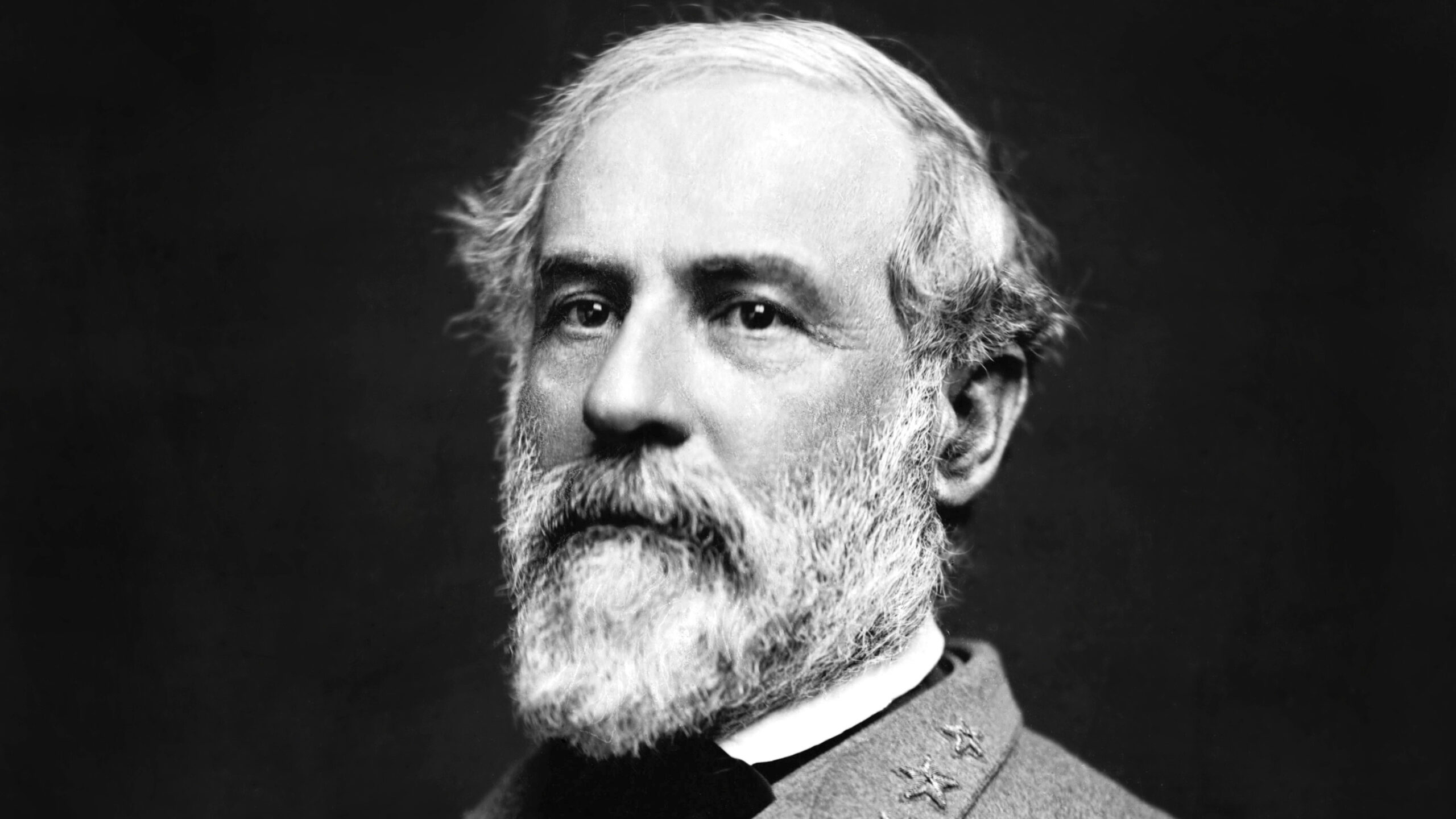

Among those leaders Seiderman selects are Benedict Arnold, who performed admirably at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777; Andrew Jackson, who defeated a superior British force at New Orleans in 1815; General Winfield Scott, who followed a brilliant strategy at Mexico City in 1847; Confederate General Robert E. Lee, the consummate strategist, at Malvern Hill in 1862; the capable Admiral George Dewey at Manila Bay in 1898; Billy Mitchell, who led the “first coordinated air-land attack in military history” at St. Mihiel in 1918; and the controversial General George S. Patton at Messina, Sicily, in 1943.

The men Sneiderman has selected to write about are certainly controversial. From treason to vanity to court martial to being relieved of command, they all had their flaws. Their bravery and heroism in combat, however, can never be denied.

White Devil: A True Story of War, Savagery, and Vengeance in Colonial America by Stephen Brumwell, DaCapo Press, Cambridge, Mass, 2006, 335 pp., maps, index.

White Devil: A True Story of War, Savagery, and Vengeance in Colonial America by Stephen Brumwell, DaCapo Press, Cambridge, Mass, 2006, 335 pp., maps, index.

To the Abenaki Indians he was known as Wobomagonda—or the White Devil. He was hated by the French and praised by the British and the Americans. His real name was Robert Rogers, and he had established a group of woodsmen, trackers and hunters and trained them to fight the Indians on their own terms. His paramilitary group would become known as Rogers’ Rangers and they would strike fear in the heart of the inhabitants of New France, which the French called Canada at that time.

During the French and Indian War, Rogers’ men performed extraordinary feats in raiding the enemy deep within his own territory. Their greatest triumph came on October 4, 1759, when approximately 140 Rangers burned the Abenaki village of St. Francis and killed most of its inhabitants.

Author Stephen Brumwell points out that atrocities were committed on both sides in a bloody and often savage conflict that claimed many lives, civilian as well as military. In the end, Rogers would be accused of being a traitor to his country and would flee America and die in London in 1795—a sad end for a man who might have remained loyal to the United States and achieved even greater fame.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments