By William J. McPeak

Bishops in battle? It’s not as unlikely as it sounds. At the Battle of Hastings in 1066, Norman Duke William, soon to be dubbed William the Conqueror, held his heavy cavalry in check until the most advantageous moment to charge the right flank of King Harold’s Saxons. Riding with him was his brother Odo, a capable military man in his own right besides being the bishop of Bayeux. Of the three great divisions of knights heading east for Constantinople in 1096 to inaugurate the First Crusade against the Seljuk Turks, that of the warriors of Provencals was led by Prince Raymond of Toulouse and another leading churchman, Bishop Adhemar de Puy, was the papal commissary. And when Scottish patriot William Wallace was defeated in 1298 at the Battle of Falkirk by King Edward I of England, it was due in part to Anthony Bek, the prince bishop of Durham, who directed the king’s right flank that day.

The thought of a lordly bishop wielding a sword or mace in combat might seem unlikely, but throughout history many clerical leaders have proven themselves to be talented and determined military commanders. The local village priest on the battlefield was actually fairly commonplace before ad 1000. It was natural to find men of the cloth—however homespun—marching with soldiers to bless them before battle or administer last rites after the fighting was over. But some of the fathers were made for more than merely turning the other cheek. They might also have carried a concealed dagger or garrote with which to more speedily administer last rites to the enemy.

Higher churchmen such as bishops often accompanied lords and king as a symbol of their spiritual unity. Some did much more. Bishops were the leaders and administrators of the early Christian church, and most candidates for a bishopric were nobles who had been appointed to the position by the king. Noble families traditionally gained power through exemplary military service. As such, they were vassals to the king and the church. The oldest son, by tradition and law, inherited the family land and title, while the youngest was usually picked to become a cleric. Although not necessarily his first inclination, it was a matter of familial duty and self-interest. Bishops, like other noblemen, held great tracts of land, and their privileges could be boundless. A king might influence the choosing of a bishop sympathetic to him to gain control of rich church lands or acquire more influence with the church for political ends. A bright offspring in clerical robes, therefore, could be a useful means of enhancing family power. If his talents included a strong right arm—so much the better for everyone involved.

The aforementioned Bishop Bek was part of an early political strategy by the English monarchy. The city of Durham, in northern England, traditionally was controlled by a loyal bishop capable of protecting the English border from the always troublesome Scots. Being given royal-like powers to rule the county, he was called the “Prince Bishop.” Nobles, knights, and lower clerics of demonstrated military ability would join the Prince Bishop’s Men, an elite force that was essentially a mercenary band. Armed clashes between the Scottish reivers, or raiders, and the Prince Bishop’s Men, were common.

There was an old saying that bishops did not carry a mace into battle to draw blood, but merely to split hairs by other means. There were blade-wielding bishops as well. European cathedrals, typically the largest church building at the center of a bishop’s territory or diocese, contained a variety of medieval swords used in various ceremonies—and many were the former battle swords of bishops. The French bishops of Caliors proudly followed a martial tradition of displaying their hardware openly in church, regularly placing their swords and helmets on the altar when they said Mass.

Many bishops took their military duties in stride and passed unnoticed in the annals of military history. Actively malicious churchmen were another matter. The tradition of the bad bishop was an old one. Some used their positions and military prowess for troublemaking and intrigue. On such intriguing bishop in 14th-century England was Thomas de Lisle, the bishop of Ely (1345-1361), who used his aggressive nature to form a gang of bravos to terrorize, harass, and otherwise extort money from local merchants and relatives of King Edward III until he finally was exiled.

As the Protestant Reformation progressed, stories focusing on bad clergy became a key point of attack on the Catholic Church. Bishops with exceptional abilities—or good connections—became archbishops who ruled over whole provinces of bishops and their ecclesiastical lands. In isolated areas without strong civil authorities, an archbishop might wield nearly ultimate power. In the medieval Holy Roman Empire (modern-day Germany), powerful archbishops ruling the ecclesiastical principalities of Mainz, Cologne, and Trier were designated as three of the seven electors of the Emperor. An archbishop could be elected a cardinal, a “Prince of the Church,” a position that made him eligible to elect or be elected pope.

The College of Cardinals at that time comprised archbishops, bishops, priests, and even deacons—but the most important figures were the archbishops. Such a figure was Ippolito d’Este (1479-1520) of the famous and ancient d’Este family of Ferrara, Italy. The son of Ercole I, duke of Ferrara, Ippolito was anything but pious, but as a younger son he was obliged to promote family interests in the religious life. A bishop at the astonishingly early age of eight, he became an archbishop, then moved on to become a cardinal at 15. As ambitious as any man in Italy, Ippolito took his nobility in stride—mistresses, expensive tastes, fine weapons for the hunt and war. He used church lands for family profit. A cardinal’s official outer dress was a dark red (cardinal) robe. Ippolito wore expensive cardinal-colored clothes—sometimes—but cut the figure of a lordly courtier with extreme hats to match. With a fiery temper and will to match his clothing, Ippolito participated in a number of military campaigns, a notable one being as commander of Duke Ferrara’s army against Venice in 1509.

Ippolito’s older brother Alfonso married Lucretia, the sister of another high-ranking man of religion—also a cardinal, but really in name only. Cesare Borgia (1476-1507) would become the embodiment of the ruthless Renaissance Italian mercenary lord. Bad followed bad. Borgia’s father, Rodrigo, had risen through church offices with bribes to become one of the most scandalous of clerics and popes, Pope Alexander VI. This indulgent clerical father intended Cesare for the church as a younger son—a matter of family power sharing. Cesare was an archbishop at 12 and a cardinal by 18. But his greed for power and glory—he was implicated in the murder of his older brother, Giovanni, the duke of Gandi—led Cesare to a different purpose.

The pope needed a muscle man to replace Giovanni. In August 1498, Cardinal Cesare was released from his ecclesiastical duties, freeing him to move against the despots of Romagna (central and eastern Italian territories belonging to the principality known as the Papal States). Cesare was not a particularly good general, although he was so physically strong that he could unbend a horseshoe or decapitate a bull with one stroke of a two-handed sword. He was not a good combat leader, either. But with a mix of good foreign and Italian mercenary captains and troops under the papal banner, he was quite successful. Cesare attempted to gobble up all the city states of Italy in the name of unity and the papacy, taking one after the other: Imola, Rimini, Pesaro, Faenza, Camerino, and Urbino.

As the Borgia name has come to suggest, Cesare’s real talents lay in treachery, bribery, and murder. From the papal fortress of Sant Angelo in Rome, he supposedly murdered four or five enemies a day. With ducal titles to cap his conquests, he was feared throughout Italy. Ironically, Cesare had brought the Papal States into better order for a martial pope to follow. Driven from Italy, he ended his days in the family’s ancestral Spain, dying on the battlefield as a common mercenary.

Popes, too, went into battle. The pope was defined as bishop of Rome. Before ad 425, any bishop was considered a pope (only after 700 did it come to mean the supreme pontiff). By then, the bishop of Rome had gained enough influence to be recognized the leader of the Roman Catholic Church. When Jesus Christ was taken by Roman soldiers in the Garden of Gethsemane, the first act of resistance came from his most enthusiastic apostle, Simon, later to become St. Peter, the first bishop of Rome, who drew his sword and hacked off the ear of one Malchus, servant of the high priest of Jerusalem. Jesus, after restoring Malchus’s ear to its usual place, told Peter to put up his sword because “he who lives by the sword dies by the sword.”

But the popes had a martial tradition of their own, for power meant having to have an army to back it up. Two of the strongest early medieval popes were Gregory the Great and Leo IV. Like royalty, the papacy had its own coat of arms and could grant noble status to its followers. Several cardinals had been papal generals, and because of the desire to control the Papal States and protect against foreign intrusions, a pope with a strong military arm was still needed. Giuliano delle Rovere (1443-1513) had an easy road to high church positions as bishop and archbishop, and by 1471 he was a cardinal by virtue of appointment by his uncle, Pope Sixtus IV. Like any cardinal with his eye on the papacy, Rovere stayed in Rome—that is, when he was not away putting out fires. In 1474, Rovere led an army to restore papal authority in Umbria. He tasked himself with the goal of recovering all the Papal States. The Borgias had begun that effort, but Rovere had no use for the Borgias. He hated their power grabbing—and meant to do something about it. But with his uncle gone and the Borgia-favoring Pope Alexander VI in control in Rome, he could do little but bide his time. Rovere hired his own soldiers to man fortresses he used as he began his struggle to check the Borgias. But he found himself having to flee to France (1493) to induce French King Charles VIII to invade. This would be one cause for the start of French dynastic designs on Italy for the next half century.

Although Rovere saw the dangers of letting in foreign powers, at the time he was more concerned with pulling Alexander from the throne of St. Peter. The French helped—and many welcomed them—until they proved no better than the self-serving mercenary lords already causing endemic warfare in the country. Finally, with the passing of Alexander VI and the sickly Pius III, who reigned less than a month after him, Rovere himself became pope in 1503—Pope Julius II. While most previous popes had family and factions to reward for their rise, the new pope was his own man in more ways than one—he had three daughters. One observer wrote: “We have a pope who will be both loved and feared.” The Venetian envoy was more descriptive: “No one has any influence over him, and he consults few or none,” he wrote. “It is almost impossible to describe how strong and violent and difficult he is to manage. In body and soul he has the nature of a giant. Everything about him is on a magnified scale, both his undertakings and his passions. He inspires fear rather than hatred, for there is nothing in him that is small or meanly selfish.”

Julius wanted to make the papacy and ultimately Italy independent of foreigners and self-seeking Italian nobles. For this, he needed complete possession of the cities of the Papal States before he could push out the French. Although a cultured man, Julius was also a warrior in spirit and disposition. He loved horses, hunting, and the feel of armor. He was not content with brainstorming with his generals and then sending them out on campaign—he had to go himself. He often acted as commander in the field, whether at sieges or on the battlefield. In full armor he directed siege gunfire and, sword in hand, rode down enemy soldiers as they retreated from his heavy cavalry. He was not called pontefice terribile (the terrible pope) for nothing.

In 1504, Julius began to methodically roll up papal enemies by making an alliance of convenience with the French and Germans to secure, among others, the papal towns of Faenza and Rimini in the Romagna from opportunistic Venice, which had grabbed them from the weakened Borgia political machine. In 1506, the pope engineered a brilliant campaign to wrest the strategic papal cities of Perugia and Bologna from Venice. He and his French, Hapsburg, and Spanish allies finally broke the Venetian domination of Italy at the Battle of Agnadello on May 14, 1509. Then it was time to deal with the French.

In 1510, Julius quickly made up with Venice to ally himself with it in order to force the French out of Italy once and for all. Julius was 68 years old, but late in the year, with winter coming on, he marched north to Bologna only to fall sick and almost be captured by the French. Recovering, he moved on to Modena and took it. In the dead of winter, Julius turned to besiege Mirandola. He took it in January 1511. Waiting to gain former allies (England, Spain, and Venice) against France, he fell gravely ill in August. Although not expected to live, he did. Overcoming the French victory at Ravenna (1512), he was able to restore the Papal States with the defeat of the French at Novara and the peace in 1513. The French were back north of the Alps at last—or at least for the foreseeable future.

Although the king of France, Louis XII, had called Julius the Antichrist, he was in reality a great patron of art, cajoling Michelangelo into doing the frescos of the Sistine Chapel and other magnificent works of art. Julius also patronized Raphael’s art and Bramante’s architecture in Rome. To his mind, he had been the proper instrument of God in getting things done. The great Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus, who hated war, did not agree. To him, the warrior pope was not deserving of heaven. In his humorous tract Julius Excluded, Erasmus depicted Julius at the closed gates of heaven, bellowing for entrance while St. Peter looked down unmoved and refused to let him enter.

The well-ordered society of 16th-century Western Europe was a far cry from conditions in the eastern borderlands—and none was worse than Hungary. With miles of flat plain ripe for invasion, fortified towns and fortresses were strategically positioned along important river fords. Since the later 15th century, invasion meant progressive incursions by the Ottoman Turks. Traditionally, the eastern border bishops and archbishops raised and supplied their own troops as a necessity against encroaching Turkish forces. The largest fortified cities were in central and eastern Hungary and had long been ecclesiastical holdings of bishops and archbishops. One of the oldest was Kolocza. Having gained the right in the 12th century to crown the Hungarian king, the archbishops of Kolocza warred frequently against Moslem Patarenes in Bosnia. Archbishop Ugrin (1219-1241), the greatest of the Hungarian archbishops, also fought the Tatars before falling at the Battle of Muhi. In a similar mold was another of Kolocza’s ruling archbishops, Paul Tomori (1475-1526), who turned to religion after his wife was killed. It was only out of national necessity that he became archbishop, and he continued to wear light armor under his robes.

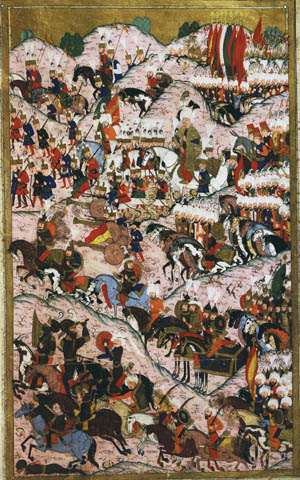

No one took a more active role in the business of military preparedness than Tomori. He was designated captain in chief along the southern borders of Hungary, which meant seeing to troop preparedness and scouting Turkish movements. By March 1526, he was receiving reports of a logistical buildup among the Turkish border fortresses, indicating that the Turkish army was preparing to march. The Turks had marched before in 1523, and the Hungarians had been able to deal with them, but not before incurring heavy losses from which they had not yet recovered. Tomori rushed north to Buda (later Budapest) to alert the young King Louis II of Hungary of the danger. Louis was hopelessly mired in bickering with self-serving nobles, and Tomori could only seethe over the decision to delay a meeting of the Diet for a month to discuss the matter. By that time, the young, ambitious Turkish sultan, Suleiman I (1494-1566), was already heading west from Constantinople with his personal troops toward Turkish-held Belgrade. His European and Asiatic vassals would meet him there.

No one took a more active role in the business of military preparedness than Tomori. He was designated captain in chief along the southern borders of Hungary, which meant seeing to troop preparedness and scouting Turkish movements. By March 1526, he was receiving reports of a logistical buildup among the Turkish border fortresses, indicating that the Turkish army was preparing to march. The Turks had marched before in 1523, and the Hungarians had been able to deal with them, but not before incurring heavy losses from which they had not yet recovered. Tomori rushed north to Buda (later Budapest) to alert the young King Louis II of Hungary of the danger. Louis was hopelessly mired in bickering with self-serving nobles, and Tomori could only seethe over the decision to delay a meeting of the Diet for a month to discuss the matter. By that time, the young, ambitious Turkish sultan, Suleiman I (1494-1566), was already heading west from Constantinople with his personal troops toward Turkish-held Belgrade. His European and Asiatic vassals would meet him there.

Back in Buda, there was talk and more talk, when mobilizing should have been the first order of business. Finally, the War Council called for every military unit, including contracted mercenaries, to meet 50 miles south of Tolna on July 2. For a battleground they chose unwisely—the uneven plains at Mohacs. With political excuses already pouring in from allied countries—Austria, Bohemia, Poland, and Wallachia all declined to send troops—raising a sufficient force in time looked hopeless. But Tomori was not one to wait passively for defeat. At Kolocza, he fitted out 3,000 horse and foot soldiers from his own diocese and headed south for the southernmost fortress city of Peterwardein on the Drava River. The Turks would make their first assault there. To reinforce it, Tomori moved quickly before a Turkish siege could begin and committed 1,000 infantry troops to bolster the garrison.

It took 15 days for the fortress to fall on July 27—not much time bought. The garrison retreated to the inner citadel after the city walls were breached and held off two massive assaults of Janissaries (the sultan’s shock troops made up of former Christian boy captives). The remaining 500 survivors were massacred. Tomori could do nothing with the 2,000 cavalrymen left to him but shadow the continued westward march of the Turkish victors. He continually sent information to the king, hoping that the regent would be moving south with his troops to intercept the Turks before they crossed the river at the strategic town of Essek.

At Tolna, the young king made that strategic decision to detach a large contingent of troops and send it southward to occupy Essek and oppose a Turkish crossing there. Incredibly, the Hungarian nobles chosen to go to Essek would not do so unless led personally by the king. Enraged, Louis had to forget reinforcing Essek and keep moving south. He arrived at the small town of Mohacs on the Danube in mid-August. There he was reunited with Tomori, now heading a force of 6,000 warriors and waiting on the opposite side of the river. Meanwhile, farther south, Suleiman and his Turkish commanders could scarcely believe that no waiting Hungarian army opposed them at Essek. In four days’ time, they constructed a pontoon bridge, and by August 24, the Turks were moving north to meet the Hungarian army at Mohacs.

Along with George Zapolya, brother of the wily John, voivode of Transylvania (who did not show), Tomori was nominated co-commander of the Hungarian forces at Mohacs. He was strongly critical of those who counseled the king to fall back before the advancing Turkish host. It would be a scandal, he said, to let half the kingdom go without a fight. He felt some confidence, for many of the king’s levies had arrived, including no less than eight other bishops. The archbishop of Gran had come with the king from Buda, while the bishops of Warasdin and Raab had joined up at Tolna. The bishop of Agram brought 700 horsemen; the bishop of Fünfkirchen brought 2,000 archers. The clerical count went on—the bishops of Bosnia, Nitria, and Vacz all arrived with their promised troops.

Tomori did his best to boost morale and fire the zeal of the Christian army. He downplayed the size of the Turkish army, noting that its ranks were swollen by irregulars, mercenaries, and camp followers who traditionally were untrustworthy in battle. Tomori felt they could defeat the enemy at Mohacs, although he could see clearly that the odds against them were formidable. There were about 20,000 European forces in hand, mostly Hungarians, but also Bohemians, Croats, and Poles as well as some Germans, Italians, and Spanish mercenaries. Arrayed against them were 70,000 fighting Turks. Francis, bishop of Warasdin, whose brother was the great frontier fighter Peter Perenyi, was prophetically sarcastic when he whispered to King Louis that the pope had better make ready to canonize 20,000 Christian martyrs.

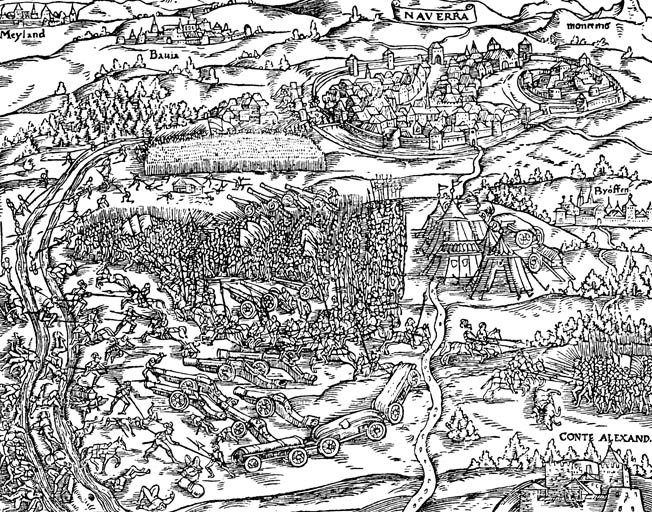

By the morning of August 29, 1526, the showdown had come. Suleiman’s host appeared at the foot of the low hills west of Mohacs. The European forces were drawn up before the town, with the marshes of the Danube to the south. Suleiman used a deep formation, with most of his cavalry stationed in the first two lines. The Turkish cannons—twice as many as the Europeans’—came next, followed by his royal cavalry and his Janissary infantry shouldering arquebuses and drawn up to protect him. Off to the north, the sultan had dispatched well over 4,000 light cavalry irregulars, called Akindjis, whose job it would be to move in quickly to outflank the Europeans if the battle looked in doubt. The Europeans were stretched in long lines of blocks to avoid being flanked. An 80-cannon train stood in front as a means of softening up the Turkish cavalry.

Tomori, as usual, rode in the front line of heavy horse in full armor. He led one of the two largest feudal cavalry formations, interspersed with infantry blocks. Among Tomori’s formation was the Hungarian light cavalry, the Hussars, better armed than their Turkish counterparts and virtually unstoppable in their headlong charges. The second line was actually two lines—the remaining squadrons of the Hungarian horse followed by the king, his personal guard, and the eight bishops with their troops arrayed on the king’s flanks.

In the late afternoon, the fiery Hungarian horsemen attacked prematurely, before the cannons could open on the Turkish cavalry. Initially, they were successful in driving back the enemy front line into its second line. But in the meantime, the Turkish cannoneers and arquebusiers unleashed a furious fire of their own that completely disorganized the Hungarian cavalry. The Hungarian right attacked and caused some disorganization—their arrows dangerously accurate and just missing the sultan—but the Janissaries pushed them back. In came the flanking Akinji cavalry. They turned the Christian host into a panic-stricken mob fleeing toward the illusive safety of the marsh, with the Turks pressing their advantage. One by one, most of the great lords went down. Six of the eight bishops fell. Tomori, trying to turn back fleeing soldiers, was killed as well. By nightfall, the unfortunate King Louis, in heavy armor, retreated south—only to fall into the marsh and drown. (He was later found still in his full armor and astride his horse.) Total European losses numbered more than 10,000.

In an uncharacteristic move, the usually modest Suleiman set up a gory display of his easy victory. He ordered the decapitation of any lordly prisoners, along with those found dead on the battlefield, and had the heads staked around his tent. That night Tomori, six of his brother clerics, and other dead lords stared with unseeing eyes upon Hungarian territory that was now in Turkish hands.

Four decades later, when Suleiman’s ongoing war against the West was decisively turned back on the Mediterranean island of Malta, it was an entire army of Christian clerics—the Knights Hospitallers of the Order of St. John—that accomplished the feat. Since its founding at the time of the First Crusade, the order had functioned as a veritable nation unto itself, beholden to no one but the Lord and the pope—a far cry from the solitary village priests who first set out in the Middle Ages to carry a sword for king and cross.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments