By Eric Niderost

It was the morning of September 1, 1898, the day before the Battle of Omdurman. Lieutenant Winston Churchill of the Queen’s 4th Hussars rode out with four squadrons of the 21st Lancers to scout the approaches to Omdurman, a Sudanese village on the west bank of the Nile opposite Khartoum, epicenter of a revolt that had rocked the very foundations of the British Empire. An Anglo-Egyptian army under Maj. Gen. Sir Herbert Kitchener was a few miles behind the cavalry screen. Kitchener’s object was to reconquer the Sudan, restore order, and forestall any encroachments from opportunistic European rivals.

The British horsemen cautiously advanced over the sun-baked plain, the eye-numbing sandy desolation relieved by a few thorn bushes, scrub, and patches of grass. Churchill and the lancers ascended a low ridge to scan the horizon. Officers raised their field glasses and were rewarded with a sweeping panorama. Omdurman itself was in sight, and Churchill recalled later that “to the left the river, steel gray in the morning light, forked into two channels, and on a tongue of land between them the gleam of a white building showed among the trees.”

The white building was part of Khartoum, capital of the Sudan, where the Blue Nile and White Nile converge to form Africa’s greatest river. Nearby, there seemed to be a long, dark smear that the British assumed was a zareba, a thorn bush barrier that commonly served as a prickly fortification in the treeless land. Some of the enemy, whom the British called Dervishes, could be seen lurking behind the barrier, confirming the officers’ first assumption.

The lancers advanced, supported by Egyptian cavalry, the Camel Corps, and some horse artillery. Dervish horsemen came forward to meet them but were sent packing by dismounted troopers firing Lee-Medford carbines at 800 yards. The lancers halted and waited for the enemy to make the next move.

About 11 am, the distant zareba suddenly sprang into malevolent life. It was made of men, not thorns—thousands of them, so thick that they made an undulating black wave. Churchill was awed by the sight. The roiling mass, he said, was “four miles from end to end and, as it seemed, in five great divisions, this mighty army advanced swiftly. Above them waved hundreds of banners, and the sun, glinting on many thousands of hostile spear points, spread a sparkling cloud.”

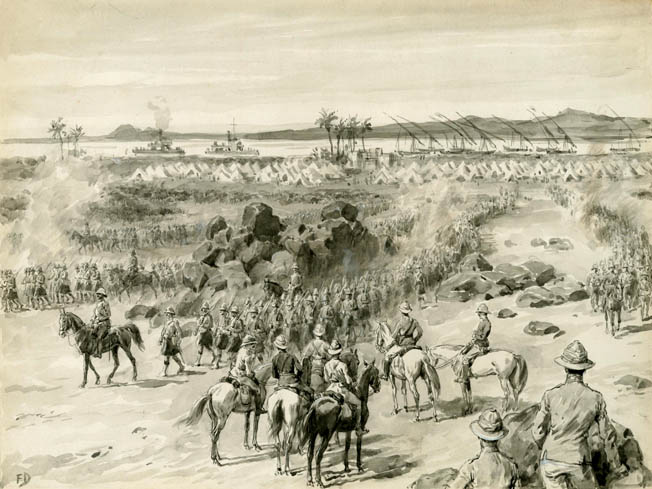

The young lieutenant rushed back to alert Kitchener to the enemy’s latest moves. Filled with a growing sense of urgency, Churchill galloped up the hillside to get his bearings. Once on the crest he could plainly see the Dervish army’s dark masses in stark relief against the brown, sandy plain. Turning around, he could also view the Anglo-Egyptian army, some 24,000 men, drawn up with their backs to the Nile. The two armies, separated by the hill’s looming slopes, could not yet see each other, but an enormous clash seemed inevitable. Churchill drank in the mesmerizing spectacle—an irresistible wall of Dervishes about to collide with an immovable force of British and Egyptian soldiers.

His sense of duty breaking the spell, Churchill pulled the reins of his horse and galloped down the hill in search of Kitchener. He briefly dismounted, in part to collect his thoughts and calm his rising excitement. The lieutenant had seen action before, in India, but this was going to be a major battle, and his pulse quickened at the idea. The action shaping up at Omdurman might well decide the fate of a continent and the destiny of a people.

The Mahdist War

In the late 19th century, Egypt was a nominal province of the decaying Turkish Ottoman Empire. Because of Egypt’s growing debts, the ruling Khedive Ismail was forced to sell his shares of the Suez Canal to Great Britain in 1876. The Suez was Britain’s lifeline to India and its empire in the Far East. Once Great Britain had a foothold on the Nile, it became unavoidably involved in the Sudan.

Egyptian rule in the Sudan was characterized by brutality and corruption. Taxes were so high that parents were regularly forced to sell their children into slavery, and government officials ruled by the whip. The Sudan was ripe for revolt. All it needed was a charismatic leader to galvanize the people and channel their hatred and resentment into political action.

In late June 1881, such a leader arose when a mystic named Muhammad Ahmad announced that he was the Mahdi, or the “Expected One,” a kind of Islamic messiah. The Egyptians were more than just oppressors, he said; they were also heretics whose railroads, telegraphs, and other modern inventions were leading Muslims away from the true path. The Mahdi’s vision was a medieval one in which the Turks, Egyptians, and infidel Europeans would all be irresistibly swept away, enabling the Sudan to return to its former glories.

Thousands of disaffected Sudanese flocked to the Mahdi’s banner, and soon the Sudan was in full revolt. The Mahdists managed to defeat several Egyptian forces that were sent against them. A 7,000-man Egyptian army under a British Army colonel named William Hicks was massacred almost to the last man in late 1883. With each defeat, the Mahdi gained prestige, followers, and modern captured rifles.

The British Withdrawal From Sudan

The Mahdi threatened Egypt itself, but British Prime Minister William Gladstone refused to be drawn into the spreading conflict. Instead, Khartoum and the remaining Egyptian garrisons were to be evacuated, abandoning all of the Sudan to the Mahdist rebels. General Charles George Gordon, an Army engineer, was sent to the Sudan to supervise the evacuation. In retrospect, Gordon was a poor choice for such a delicate mission. Eccentric and charismatic, he was a devout Christian who felt that he was an instrument of God. Once in Khartoum, he decided to disobey orders and stay in the Sudan. He hoped by doing so to pressure the British government to send more troops, but Gladstone refused to play into the general’s hands. In April 1884, Gordon and his remaining forces were besieged inside Khartoum. The siege dragged on for nine months.

After a public outcry, Gladstone relented. But when the advance party of a British relief expedition finally reached Khartoum in January 1885, they found that the city had fallen two days earlier. The city had been sacked, its men ruthlessly butchered, the women raped and sold into slavery. Gordon had been fatally speared and his severed head presented to the Mahdi as a trophy.

Gordon’s death produced a predictable uproar in Great Britain. Overnight, the eccentric engineer became a national martyr, seemingly sacrificed on the altar of political expediency. Queen Victoria herself was appalled, noting firmly in her diary that “the government alone is to blame.” Unshaken by the torrent of public protest, Gladstone withdrew all British troops from the Sudan.

“Cape to Cairo”

The Mahdi did not live long to celebrate his triumph, dying of typhus three months after taking Khartoum. Just before he died, the Mahdi chose Abdullah al-Taaishi, a member of the warrior Baggara tribe, as his hand-picked successor. Abdullah was now the khalifa, or deputy of Allah. The khalifa continued the Mahdi’s hard-fisted religious totalitarianism. The few tribes that resisted were ruthlessly exterminated. Villages were depopulated and famine stalked the land. Many Sudanese believed that they had exchanged Egyptian tyranny for another kind of oppression, one even more ruthless because it was clothed in the sanctity of religion.

In the meantime, Egypt became a British colony in all but name. Sir Evelyn Baring was appointed the khedive’s chief adviser on economic, military, and political affairs. The Egyptian Army was re-formed and trained under the supervision of British officers. The memory of Gordon’s demise remained fresh in the minds of the British public. In 1896, the new prime minister, the Marquess of Salisbury, decided that the time was ripe to return to the Sudan. In this, he was motivated more by international politics and imperialism than by any thoughts of personal revenge.

The French were in equatorial Africa, pushing east. If the British dreamed of a “Cape to Cairo” domain that stretched the length of the continent from north to south, the French envisioned a similar west-to-east “Atlantic to Red Sea” empire. Success of the French vision would mean control of the sources of the Nile—and whoever controlled the Nile controlled Egypt. The Sudan had to be reconquered to forestall Gallic territorial ambitions.

Kitchener’s Sudan Military Railway

General Herbert Horatio Kitchener was appointed sirdar, or commander, of the joint Anglo-Egyptian forces. Standing over six feet tall, with a bristling handlebar mustache, Kitchener seemed the very embodiment of John Bull. He was cold, methodical, and seemingly emotionless, a man who used the army as an instrument of his will. As a soldier, he was far from brilliant, but he excelled in logistical planning—always a must in Africa‘s inhospitable countryside.

As Kitchener pored over his maps, a plan began to form in his mind. The Nile was his lifeline, yet shipping supplies upriver was a laborious, time-consuming process. The river was punctuated by six cataracts, stretches of rocky rapids that were difficult to cross. The Nile also added mileage as it curved west, its meandering ribbon of water impossible to fortify at all twists and turns.

Kitchener decided to build a railway straight across the arid Nubian Desert, a shortcut that would eliminate 900 miles of the river’s curve between Wadi Halfa and Abu Hamad, north of Berber. The railroad would be 400 miles in length, including a stretch of pre-existing line that hugged the Nile. The real challenge would be the 230-mile shortcut through the desert, a desiccated region infamous for not having water of any kind.

Most experts considered the desert portion of the railway impossible to build. But Royal Engineer Edouard Girouard, an experienced Canadian railway builder, was more than willing to try. It was a gargantuan task, made worse by a harsh climate and lazy, incompetent, and dishonest subordinates. Despite an outbreak of cholera and a bad case of sunstroke suffered by Girouard himself, work continued throughout the summer, with temperatures reaching 116 degrees in the shade. When a massive rainstorm washed away 12 miles of track, 5,000 men worked day and night for a week to repair the break.

By the time Abu Hamad had been captured on August 7, 1897, the Sudan Military Railway was roughly halfway though the Nubian Desert. The ever-impatient Kitchener wanted the remaining 120 miles to Abu Hamad completed quickly, and Girouard pressed on. Up to three miles of track was laid each day. While the railroad was being built, Kitchener marched south by stages. There were several small-scale battles with the Mahdists, all resulting in defeat for the khalifa’s forces. The months dragged on, but slowly the Anglo-Egyptian army closed in on Khartoum. The railway shortcut was finally completed when it reached Atbara on July 3, 1898. Girouard had achieved the impossible. By August 31, Kitchener was only 18 miles from Khartoum.

Making a Stand at Omdurman

The general had little time to savor his progress—the khalifa still had to be defeated. It was feared that the khalifa would retreat into the desert vastness, away from the railroad and the vital Nile supply line. On reflection, however, Kitchener was sure that the Mahdists would make a stand at Omdurman. To Europeans, Omdurman was a primitive collection of shoddy mud huts clinging to the western banks of the Nile, but to the Dervishes it was almost a second Mecca. Omdurman was the khalifa’s capital and the site of the Mahdi’s elaborate tomb. If the khalifa gave it up without a fight, he would lose face, and his position as God’s chosen deputy would be severely compromised.

Now, as Churchill galloped up to his commander in chief, the stage was set for a final reckoning at Omdurman. Saluting, Churchill announced that he was a messenger from the 21st Lancers. He reported that the Dervish forces were on the move, marching rapidly in Kitchener’s direction. “How long do you think I have?” Kitchener asked. “You have got at least an hour,” Churchill replied, “probably an hour and a half, sir, even if they come at their present rate.”

Kitchener’s gunboats were drawing closer to Omdurman, pushing their way past the khalifa’s riverside forts. Once past the forts, the gunboats opened fire with their 40-pounder cannons. They were accompanied by British howitzers that had been placed on the eastern bank. The shells rained down on Omdurman, each explosion marked by gouts of flame that rose through great clouds of dust and flying fragments of stone. The Mahdi’s tomb was hit several times, leaving great gaping holes in the white dome. Inexplicably, the khalifa halted his forces for the night.

Deciding When to Attack

As the sun sank beneath the horizon, the Anglo-Egyptian army retired to its camp along the Nile. Sudanese scouts were sent out to give early warning of a night attack. That evening, the khalifa presided over an acrimonious council of war. His son Osman Sheikh al-Din wanted to attack at daybreak, immediately after morning prayers. He counseled, “Let us not be like mice or foxes sneaking into our holes by day and peeping out at night.” Ibrahim al-Khalil favored a stealthy night assault—the very thing Kitchener feared the most. If the zareba was breached at night, rifles and artillery would be useless in the pitch-black darkness. Perhaps British discipline would still triumph, but Kitchener’s army was sure to suffer heavy casualties in the confused and bloody melee.

The khalifa decided to attack in broad daylight. From the Sudanese point of view, it was a decision of almost criminal stupidity. Kitchener’s fortified camp was well positioned to meet a Dervish attack. It was semicircular in shape, about 1,200 yards wide at its widest point. The south end of the perimeter was protected by a line of mimosa thorn bushes, and the northern end featured a double line of trenches.

Major General William Gatacre’s British division occupied the zareba portion of the defenses, comprising such famed regiments as the Grenadier Guards, the Rifles, Lincolns, Warwicks, and Cameron Highlanders. Gatacre was known as a hard-driving general whose men had nicknamed him “Back-Acher.” The Egyptian troops under Maj. Gen. Sir Archibald Hunter occupied the trenches facing west and north. Hunter was a veteran of the failed Gordon relief expedition and knew his Egyptian and Sudanese soldiers well. Colonel Hector MacDonald, one of Hunter’s subordinates, had come up from the ranks and personally trained his brigade to a peak of efficiency.

Kitchener’s army had 46 artillery pieces and a battery of Maxim machine guns. The disciplined fire of British troops was almost as good as an artillery barrage. Each British Tommy was armed with an eight-shot Lee-Medford rifle and 100 rounds of hollow-point “dum-dum” ammunition, bullets that caused massive internal injuries wherever they struck.

The Battle of Omdurman Begins

Buglers sounded reveille at 3:40 am on September 2. British troops gathered behind the zareba and were told to lie down until the battle started. Friendly Sudanese and Egyptian troops swarmed into the trenches, making sure their single-shot Martini-Henry rifles were in working order. A few native huts in the rear served as protection for the sick and wounded, and the army’s menagerie of camels, horses, mules, and donkeys were picketed close by.

The 21st Lancers, on point, moved out of the zareba at about 5 am and headed toward the looming mass of the mountain, Jebel Surgham. Churchill accompanied them, mounted on a sturdy gray pony. He had a bad shoulder, so he decided that wielding a saber was out of the question. Instead, he would rely on a Mauser pistol he had purchased in London. The young officer loved the 10-shot weapon, which he called a “ripper.”

Perched on the slopes of Jebel Surgham, Churchill and the lancers had a ringside seat to the Battle of Omdurman’s opening moves. The Dervish army began to slowly climb the slopes, their advance described by one embedded reporter as “a moving, undulating plain of men.” The khalifa’s 52,000-man army stretched for some five miles, a frightening yet mesmerizing pageant of motion, color, and sound. Most followers of the khalifa wore the rough jibba, a woolen tunic that sported black patches as signs of humility before Allah. Human nature being what it is, many Dervishes had gotten their wives to sew on additional swatches of yellow, blue, and red.

There were several major divisions within the Mahdist army. Osman Azrak and Osman Sheikh al-Din would lead the attack under the latter’s dark-green battle flag. Sheikh al-Din, the khalifa’s son, had the most riflemen in his division, warriors using captured Remington and Martini-Henry rifles. Sheikh al-Din would be supported on the right by Ibrahim Al-Khalil’s elite troops under a white banner covered with quotes from the Koran. Under a red flag, Khalifa Sherif—not to be confused with the Mahdist leader—and his 2,000 Danagla tribesmen were positioned on the right.

The khalifa himself stayed in the rear with a large reserve of around 20,000 men, sheltering behind Jebel Surgham’s rocky mass. Surrounded by a bodyguard, the Dervish leader had a great black flag carried before him. The sable banner was huge, about two yards square, and covered with texts from the Koran and the Mahdi’s sayings. It was attached to a large bamboo pole about 20 feet long, and wherever it went it was acclaimed as a talisman of victory.

The Dervish plan was simple: The first waves would crash against the infidels’ zareba. The khalifa’s black flag division would be held in reserve, together with Ali Wad Helu’s 5,000 Degheim and Kenana tribesmen. If the first waves were successful, the reserves would come forward to complete the victory. If not, the khalifa would have enough intact forces to attempt a second round of attacks.

Thousands of spear points twinkled and gleamed in the sun, swords were brandished with fervor, and war drums beat a throbbing tattoo. Mounted warriors sported helmets and chain-mail armor that seemed a throwback to medieval times. Shouts in Arabic of “There is no God but Allah, and Mohammed is his Messenger!” and “Mahdi!” sounded from thousands of throats, a swelling chorus that seemed to cause the very earth to tremble. The shouts grew louder when the tribesmen saw the infidels’ zareba in the distance. The Dervishes started forward at the run, banners flying, while emirs on horseback urged them on.

The Bloody First Phase

About 50 yards from the zareba, two shells exploded, the bursts gouging holes in the gravel and red sand. The shells were from Mahdist artillery, but the guns were so poorly served that they fell short. The Anglo-Egyptian artillery replied, but with a far more deadly accuracy. On the right, Ibrahim al-Khalil and his men pressed forward, spilling over the ridge that marked Jebel Sergham’s eastern boundary. Guns from the 32nd Field Battery opened up at 2,800 yards, a rain of shells that produced terrible carnage. As many as 20 shells hit the advancing black mass in the first minute, throwing up dirty blossoms of flame and red dust with each detonation.

Men were decapitated, eviscerated, torn limb from limb; yet others came forward with incredible courage and resolution. Al-Khalil was blown from the saddle, tumbling in the dirt when his horse’s head was nearly severed by a shell fragment. Mounting a fresh horse, he led his men forward—but by this time they were within range of the Maxim machine guns and the Lee-Medford rifles. The machine guns opened up, chattering a steady hail of death, and the Grenadier Guards stood up and poured a steady fire on the enemy’s shredded ranks. Ibrahim al-Khalil was shot in the head and chest, and the bloodied survivors reluctantly fell back.

Sheikh Osman al-Din’s attack in the center was equally disastrous. British shells tore bloody gaps in the ranks and tossed men like rag dolls into the air, yet the Dervishes refused to give up the fight. A carpet of spent cartridge shells gathered around each British soldier, and rifles grew so hot that they had to be replaced by weapons from the reserve.

The Dervishes fared no better on the left. The Sudanese regiments had little love for their Mahdist countrymen, and some probably wanted revenge for the khalifa’s depredations. The Sudanese opened up at 800 yards, great gouts of smoke, flame, and lead spouting from their Martini-Henrys. Dervish leaders pressed forward, but human flesh and blood could not stand against this hurricane of lead and metal.

The Last Formal Cavalry Charge in British History

The first phase of the Battle of Omdurman was over. The plain between the Keriri Hills and Jebel Surgham was carpeted with thousands of Mahdist bodies. The wounded crawled among the dead, many of them leaving a bloody trail of missing arms, legs, or feet. “Cease fire!” Kitchener shouted, then ordered the army to turn south and head straight for Omdurman. The general was afraid the khalifa might make a stand in the city, and the thought of house-to-house fighting was daunting.

As a first step, Kitchener ordered Colonel Rowland Martin and his 21st Lancers to reconnoiter the city and cut off the retreat of any fleeing Dervishes. Martin was happy to comply; the regiment was itching for action. The lancers advanced at a walk, then spied a line of Dervishes about a half mile away. The Dervishes—only about a 100 or so skirmishers—started to fire on the British horsemen. Martin ordered a “right wheel into line,” which a bugler spat out in musical notes. The 320 troopers turned about smartly, readying themselves for the regiment’s first full-blown charge and the last formal cavalry charge in British history.

The lancers charged with fine style, lances leveled and swords drawn. But when they reached their objective they were shocked to find that the ground fell away five feet to expose a khor—a dry watercourse—filled with 3,000 warriors 10 to 12 ranks deep. The 21st was committed—there was nothing left to do but increase the pace and hope for the best. The subsequent impact was terrible, as horses plunged headlong into the enemy mass. Around 30 troopers were unhorsed as they crashed into the packed ranks, and perhaps as many as 200 Dervishes were laid low, trampled and stunned. But the Mahdists recovered quickly—this was the kind of warfare they understood.

Each lancer found himself engulfed in a sea of enemies who thrust spears and slashed swords with wild abandon. Troopers were pulled from their mounts, surrounded and hacked to pieces. Bridles were cut, stirrup leather slashed, and horses were hamstrung in an attempt to bring them down. Churchill was one of the lucky ones, partly because he was on the far right, where the mass of Dervishes was thinner, and also because he was wielding a pistol. Even so, he barely escaped with his life. Finding himself closely surrounded by several dozen Dervishes, Churchill emptied his Mauser as they pressed closer to finish him. One assailant, swinging a curved sword, got so near the pistol he bumped into it. Churchill wheeled away at the last moment and galloped to safety.

The surviving lancers managed to get out of the khor and paused to re-form. The melee had lasted only two minutes, but in that short span of time 22 men had been killed and another 50 wounded. Some 119 horses had been slaughtered. The 21st Lancers had covered themselves in glory, but at a high price in blood. Once he recovered from the euphoria of battle, Churchill noted “horses spouting blood, men bleeding from terrible wounds, fish-hook spears stuck right through them, men gasping, crying, expiring.” One nearby lieutenant had been wounded in the shoulder and leg, his hand almost severed by a sword strike, and a sergeant’s face “was cut to pieces … the whole of his nose, cheeks and lips flapped red bubbles.”

Gordon Avenged

The battle was not yet over. Kitchener mistakenly believed the Mahdist army was broken. The Dervishes had suffered grievously, but most of the Khalifa’s black flag division and Ali Wad Helu’s corps were still intact. Colonel Hector MacDonald’s 1st Egyptian Brigade, a rear guard composed of Sudanese and Egyptians, was dangerously exposed. If the khalifa could pounce on MacDonald, he might annihilate the Scotsman before other units could come to his aid. Kitchener’s whole army could be taken in flank and rear while still on the march and rolled up.

Unaware of the danger, Kitchener was irritated. “Can’t he see we’re marching on Omdurman?” the general complained. “Tell him to follow on.” Obeying, General Hunter relayed a message to MacDonald to withdraw. But just about the time he received the message, MacDonald became aware of the danger. “I’ll nae do it,” he said firmly in his Scots brogue. If he withdrew, his men would be slaughtered. When the khalifa’s black flag division came forward at the run, they were met by disciplined volleys from the British troops. As before, modern firepower trumped medieval courage, and the attack faltered and broke off.

Just then, Ali Wad Helu’s warriors swept in from the north, threatening to hit MacDonald’s troops in flank. The Scotsman coolly appraised the situation and swung the 11th Sudanese Battalion to meet the new threat. MacDonald’s brigade was now in an L shape, firing so rapidly that many men didn’t even aim. The Dervish horde, wilting under heavy fire, started to lap around the 11th’s flank, seeking to exploit a space they saw between the 11th and 9th Battalions. The 2nd Egyptian Battalion plugged the gap on the run, firing into their opponents at point-blank range. The attack failed. Watching in the rear, the khalifa accepted defeat and fled to distant Kordofan, leaving behind his great black flag as a trophy for the victors.

The skill and bravery of the Sudanese and Egyptian troops had saved Kitchener from disaster. Well-deserved praise was also lavished on MacDonald’s men. MacDonald himself gained the affectionate sobriquet, “Fighting Mac.” Winston Churchill added another notch to his budding legend.

Rarely had a major victory been won at such a small cost. The Anglo-Egyptian army’s casualties were 47 dead and 340 wounded. By contrast, the Mahdist army lost almost 10,000 killed, 13,000 wounded, and 5,000 captured. The khalifa was eventually tracked down a year later and killed in battle. However indirectly, Gordon had been avenged.

Kudos for a brief, readable and exciting account of a pitiful moment in military warfare and world history. For the most part, little is well known about British exploits and influence in Africa here in the U.S. Readers of this short account may enjoy reading Thunderbolt, by Lewis Sorley, a prominent U.S. military history historian. Likewise those interested in the conflict in Vietnam may enjoy my four-part film series entitled “The Long Home Home Project” available on Amazon Prime here in the U.S. Thank you again for having this available online.

Great description. Thanks for it. An enjoyable and informative read.

Only one small correction:

you wrote that “eventually the Khalifa was tracked down and killed in battle”. That gives a false impression. Muhammad Ahmad was the Mahdi who captured Khartoum and rallied the forces that Kitchener defeated at Omdurman. He did NOT die in battle but died unexpectedly on June 22nd 1885 from typhoid, six months after the death of General Gordon.

I think you might be allowing people to mix up the death of the Mahdi with his successor.

Interesting article, but the title is wrong.

The Last British Cavalry Charge

Huj, November 8th 1917

At 1.30pm on November 8, 1917, just outside Huj, a small dusty town deep in the Sinai Desert, 181 horses of the Worcester Yeomanry Cavalry ridden by men armed with sabres, galloped into a force of 20,000 Turks, 21 German field guns and three Austrian 5.9 Howitzers. It was to become the final cavalry charge of the British Army