By David Norris

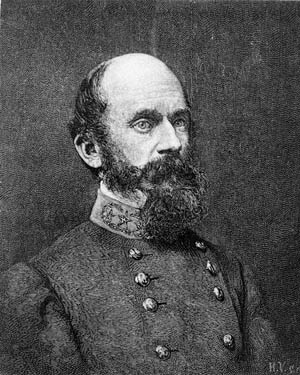

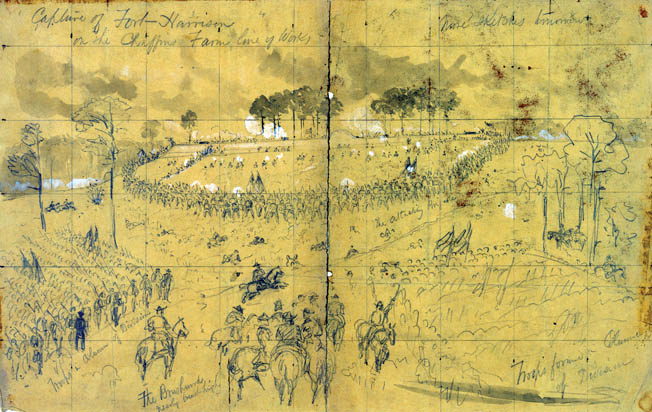

Reports of a massive enemy force crossing the James River to assail the paper-thin Confederate lines defending Richmond reached Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell before dawn on September 29, 1864. Ewell rode immediately to Fort Harrison, the point where the Federals were hammering his lines. Galloping ahead of reinforcements, Ewell met only the fleeing remnants of the fort’s defenders. Years later, R.S. Rock of the Goochland Artillery would recall that the scattered gunners and foot soldiers “were running so fast that it seemed the balls thrown at us from our own guns that had been captured and turned toward us couldn’t come fast enough to catch us. He tried to rally us, and I heard him say: ‘What in the hell are you running for?’ A soldier as he ran by him like the wind yelled back: ‘Because we can’t fly.’” The general found a huge and growing gap in the Confederate shield around the capital city. Substantial reinforcements were hours away. Ewell was too late to save Fort Harrison. The next few hours would show whether or not he was too late to save Richmond itself.

The Union’s tightening siege of Richmond and Petersburg was the focal point of the war in Virginia in late 1864. With Ulysses S. Grant in command of the Army of the Potomac, a series of Union offensives kept unrelenting pressure on the Confederate lines. Four separate offensives launched by Grant had failed to break through to the enemy capital, but each had forced General Robert E. Lee to lengthen his defenses and dilute troop strength to man the new sections. If the protective bubble burst anywhere around Richmond or Petersburg, the Army of Northern Virginia could not hold the capital of the Confederacy.

Grant planned a fifth major push for late September 1864. The new plan envisioned two simultaneous attacks: Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler’s Army of the James would move directly against Richmond, while Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade’s Army of the Potomac would attack the Petersburg defenses. With Petersburg under direct threat, Confederate troops could not be spared to counter Butler’s operations. This left Butler with a chance of piercing the enemy defenses and sending several thousand troops into Richmond before the rest of the Union Army could pour in. If Butler failed, there was still a chance that he would create enough of a distraction that the Army of the Potomac could break through the protective shield around Petersburg and seize the vital Southside Railroad. Closing that line would make supplying Petersburg by rail almost impossible. Without Petersburg, the defense of Richmond would crumble anyway, and Lee would be forced to abandon the capital.

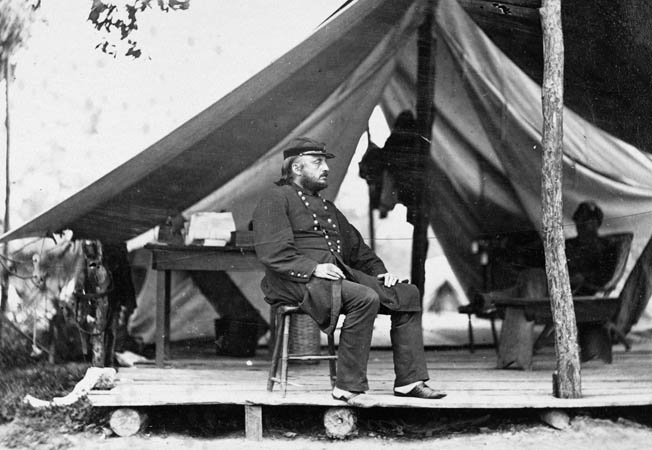

The Union commander tasked with seizing Richmond was one of the Civil War’s most controversial and contradictory generals. Butler, a politician and lawyer by training, burst on the military scene at the start of the war, ramming through secessionist obstruction in Baltimore to bring the 8th Massachusetts to Washington to protect the nearly defenseless capital. Like many political generals, he had led his share of disasters, starting with the embarrassing Union loss at the Battle of Big Bethel, Virginia, on June 10, 1861. As military governor of New Orleans, he had outraged Confederates with his harsh treatment of secessionist dissenters, particularly women, and he was also accused of corruption and theft.

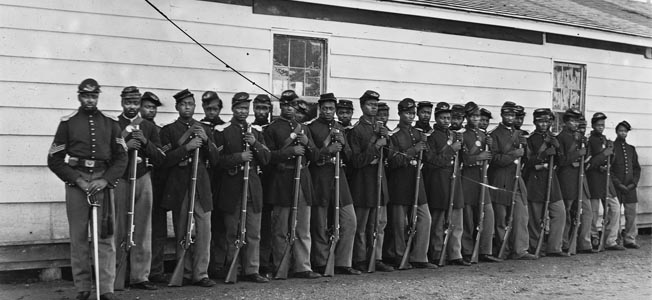

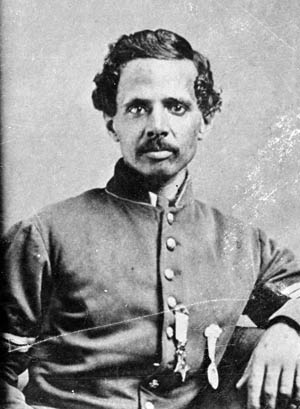

Butler’s most positive contributions to the Union were his respect for and considerate treatment of freed slaves. Early in the war, slaves who escaped from Confederate owners into the Union lines were handed back. Butler declared that such escapees from disloyal masters were “contraband of war” and would not be returned to captivity. His policy was soon adopted by all Union authorities. Butler also promoted the enlistment of black troops during his time in Louisiana. In 1863, he was transferred to Virginia and given command of the two corps comprising the Army of the James. His troops by 1864 included an African American division commanded by Brig. Gen. Charles J. Paine in XVIII Corps and a black brigade of X Corps under Brig. Gen. William Birney.

Union attacks against Richmond had come from the east since the Peninsular Campaign of 1862. Confederates augmented the natural defenses of swamps and creeks in Henrico County east of the city by building an increasingly complex network of earthworks studded with batteries and forts. Eventually the works extended south to envelop the city of Petersburg and the rail connections that linked that point with Richmond and the rest of the Confederacy. Many miles of defenses protected Richmond, but there were not enough troops to man them effectively. In September 1864, with anticipation of an attack at Petersburg, the Richmond sector was drained of manpower.

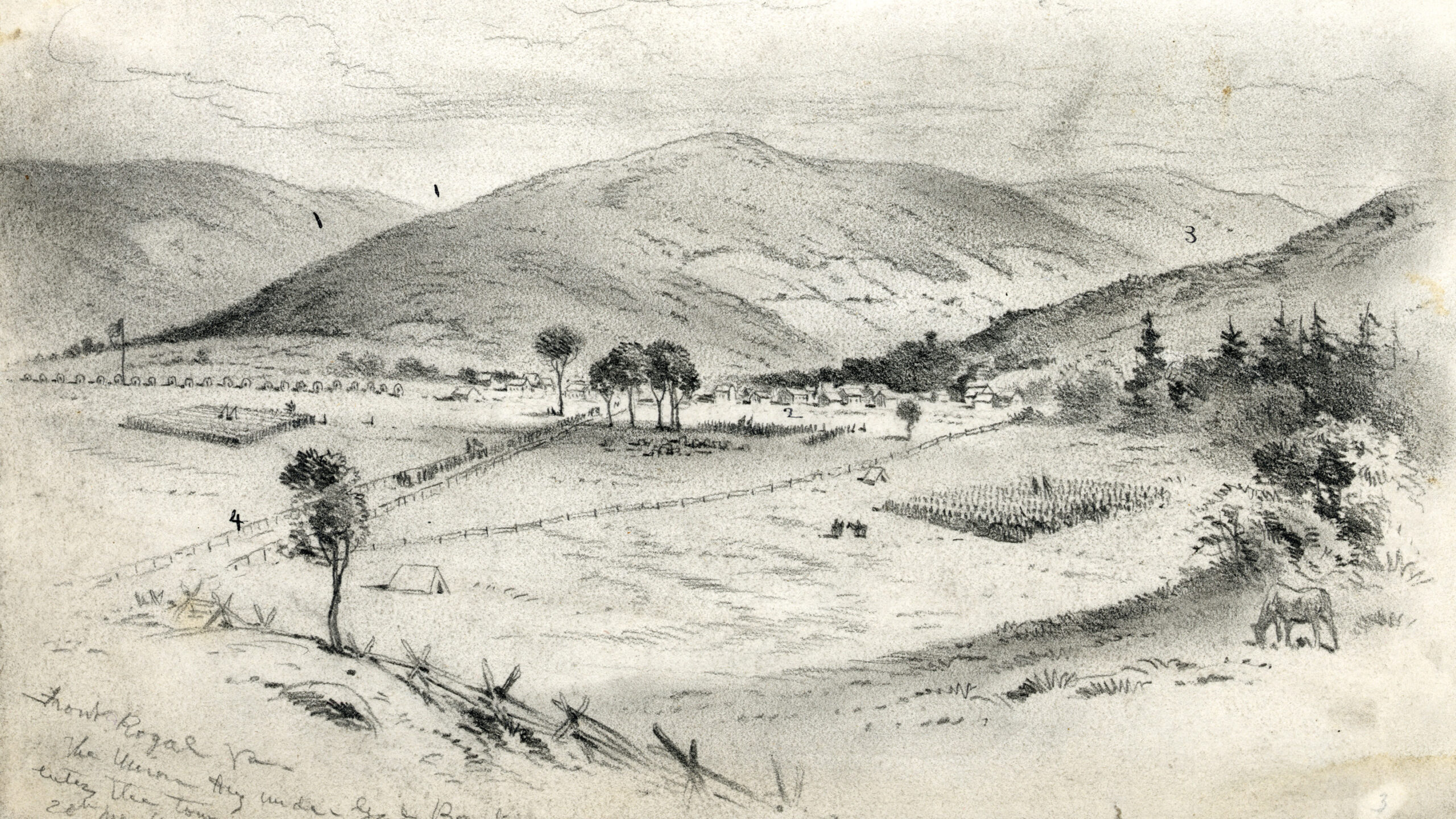

Quiet Crossing of the James River

In preparing his portion of Grant’s fifth offensive, Butler carried out his work in unusually effective secrecy. No one outside of the highest levels suspected anything was planned until his troops were surprised with orders to move out on the night of September 28. For his part, Maj. Gen. E.O.C. Ord, commander of XVIII Corps, issued no written orders, and his verbal orders went out only after nightfall. Such tight security was deemed necessary to prevent the spies from deserting and warning the Confederates.

In the camp of one of Ord’s regiments, the 118th New York, Major John L. Cunningham heard tattoo sounded to end a routine day. The regiment’s brief rest ended when staff officers appeared with unexpected new orders to move out. As the camp was within sight of Rebel sentinels across the James, the tents were left standing while the soldiers were herded to the corps headquarters. There, they handed over their Enfield muskets in exchange for seven-shot Spencer repeating rifles.

With the rest of their corps, the 118th New York marched to the James River. At Aiken’s Landing, they found engineers laying a pontoon bridge of some 60 boats so quietly that the men could scarcely hear them at work. About 3 am, the bridge was ready and the troops filed across. Muffled with dirt, the bridge planks made little noise as the soldiers plodded across, and for the time being the Confederates seemed unaware of the movement.

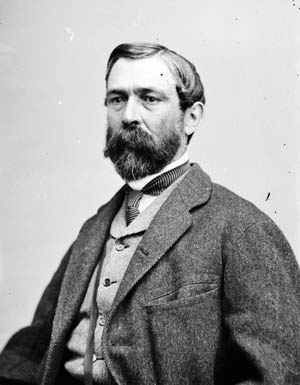

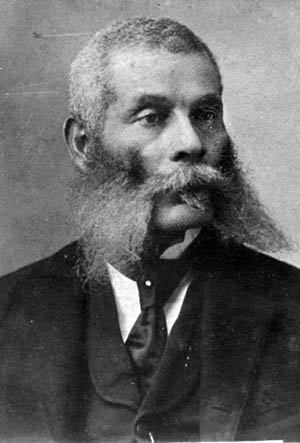

Half a mile downstream, Birney’s X Corps crossed the James by pontoon bridge at Deep Bottom. Born in Alabama in 1825, Birney was a son of James Gillespie Birney, an abolitionist politician and journalist from Kentucky. Birney’s corps included the all-African American division of Brig. Gen. Charles Jackson Paine. A lawyer by profession, Paine came from an aristocratic Boston family. His great-grandfather Robert Treat Paine signed the Declaration of Independence. Charles Paine became the colonel of the 2nd Louisiana Native Guard (later the 74th United States Colored Troops, or USCT), one of the first African American units of the Union Army, on October 23, 1862. Early in 1864 he transferred to the eastern theater and joined Butler’s staff.

Although the Confederates spotted them once they were across, Ord and Birney were ready to stab at Richmond at dawn on September 29. Birney’s 8,000 troops would move north of the crossing and hit a line of Confederate works at New Market Heights. Brig. Gen. August Kautz’s cavalry would ride around his right and push up the Darbytown Road toward the Confederate capital. To their left, Ord would take the Varina Road to attack Fort Harrison, a key strongpoint in the main ring of works around Richmond.

The Confederates at New Market Heights

Deep Bottom, the landing point of X Corps, was at the top of an oxbow bend of the James River. About three-quarters of a mile to the north was a line of Confederate earthworks at New Market Heights. Perpendicular to the main Richmond defenses, they had been constructed to fend off potential Union attacks from the James. The community of New Market was 11½ miles from central Richmond by road. Protected on the left by the lowlands of Bailey’s Creek, the Confederate works ran east to west, parallel with the New Market Road for half a mile. The line continued at the same angle while the road veered diagonally away to the north. Taking advantage of high ground known as New Market Heights, the works looked down on the valley of Four Mile Creek. Several Union attacks had been repulsed around New Market Heights in previous months, and the area was all too familiar to the bluecoats.

Along New Market Road, 1,800 Confederates manned one mile of works. Below the entrenchments was an abatis, a tight barrier of interlocking trees, branches, and brush. On the left, the 1st Rockbridge Artillery provided cover with their guns. Brig. Gen. Martin Gary’s brigade came next, followed by the Texas brigade of Brig. Gen. John Gregg to Gary’s right, and then a detachment of the Richmond Howitzers. Gregg was at Fort Harrison, leaving command on the ground to Colonel Frederick S. Bass. Brig. Gen. Alfred Terry’s division held the Union right, facing Gary and the Rockbridge Artillery. Brig. Gen. Robert Sanford Foster’s division waited in reserve.

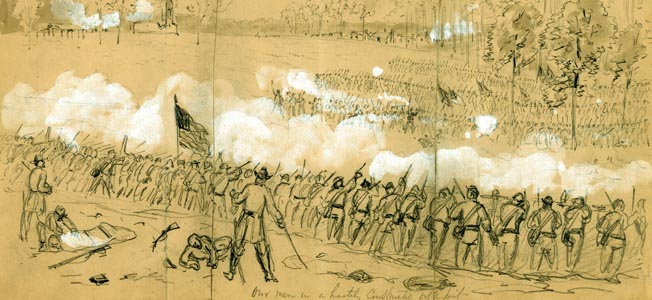

Paine’s division held the Union left, facing Bass’s Texans and the Richmond Howitzers. Early that morning they were arrayed on high ground south of Four Mile Creek, where they were instructed to lie down and wait for further orders. Colonel Samuel Duncan’s brigade was sent ahead first, but they were blocked by the abatis. Colonel Alonzo Draper moved his brigade forward and to the right to support Duncan. Draper took skirmisher fire from the woods until he reached the creek’s ravine.

After half an hour, Draper moved his men ahead in double columns. Emerging from a stand of young pines, they burst into the open 800 yards from the enemy’s works. Charging across the field, they lost many men to heavy enemy fire and found themselves mired in the wetlands of Four Mile Creek, 30 yards from the Confederate lines. Slogging through the water, they formed ranks again on the north side of the creek. There, wrote Draper, “The men generally commenced firing, which made so much confusion that it was impossible to make orders understood.” Amid the chaos, Draper was unable to communicate the order to charge, and the brigade remained stranded and tangled in front of the abatis. All the while, men were falling by scores.

For half an hour, under heavy enemy fire, Draper’s men hacked at the abatis with axes. Draper’s aide-de-camp fled from the field. But to Draper’s relief, Confederate fire began dying away. The colonel ordered each regimental commander to rally his men around the colors and charge. Draper’s regiments were short of officers. That morning, the 550 men of the 5th USCT went into action with only one officer per company, and managed that only because the adjutant took command of one of the companies.

“Better Men Were Never Better Led”

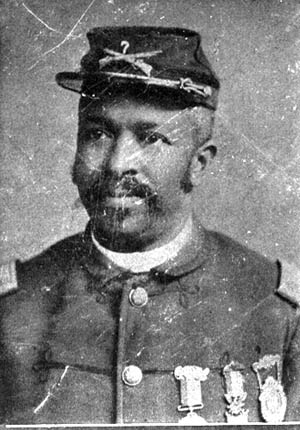

By the time they reached the New Market Road works, several companies were missing their officers. Stepping into their places to take command under fire, four sergeants in the 5th USCT and four in the 36th USCT became de facto company captains—the first African American soldiers to command troops in combat. Pouring through the abatis, the Union soldiers rushed up the slope to the Confederate breastworks. Unknown to the Federals, the Confederate fire had slackened because Bass and Gary had received orders to abandon their position and reinforce the lines closer to the city, which were coming under attack from Ord’s XVIII Corps. As Paine’s troops reached the ramparts, enough Rebels were still in place to keep up a lively fire.

For their actions in the final dash to the entrenchments several men were commended in after-battle reports. Among them, Private James Gardiner charged ahead of his company and into the Confederate works. He shot and bayoneted an officer who was trying to rally his men. A musket ball struck Corporal Miles James and shattered his upper left arm bone. James stayed on his feet, urged his men forward, and somehow loaded and fired his musket with his one good arm.

Paine’s strategy of throwing in his regiments piecemeal resulted in needlessly high casualties for a position that was being abandoned anyway. Confederate soldiers remaining in line delayed the Union advance and inflicted heavy losses on the enemy before commencing an orderly evacuation. The sacrifices of Paine’s men had meaning far beyond the value of the ground taken. Until that day, the worth of black soldiers was doubted by much of the Union Army in Virginia. Paine’s brigade sufferedmore than 1,000 casualties, most of them in front of the New Market Heights works. “Better men were never better led,” wrote Butler. “The colored soldiers by coolness, steadiness, and determined courage and dash have silenced every cavil of the doubters of their soldierly capacity.”

“Heave After Them—Double Quick!”

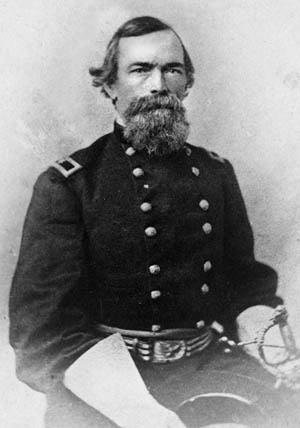

While Birney’s X Corps crossed at Deep Bottom, Ord’s men in XVIII Corps stepped off the Aiken’s Landing pontoon bridge. Brig. Gen. George J. Stannard’s 1st Division marched inland on the Varina Road. Cunningham and the 118th New York, with their Spencers, were in the lead on the right of the Union skirmish line. About 6 am, as the sun rose, they stepped onto a ridge one mile from the river. Turning around, they could see a dark line of blue-coated troops still filing across the bridge. Closer at hand, they came under a sputtering fire from Confederate pickets. Cunningham heard the “lumberman voice” of his brigade commander, Brig. Gen. Hiram Burnham, booming, “Heave after them—double quick!”

Cunningham’s men rushed forward and drove the enemy pickets from a shallow line of trenches. “The crack of our seven-shooters, the cheering of our men as they pursued the surprised ‘Johnnies’ through the woods; the beauty of the morning and its bracing air; the forest clad in autumnal colors—all added spirit and enthusiasm,” wrote the major. Dashing through an abandoned camp, where breakfast was left cooking, Cunningham’s men came within sight of Fort Harrison. In the glare of the early morning, the Rebel fort loomed up in the sunlight with heavy guns dotting its parapet.

Fort Harrison vs Signal Hill

Butler’s moves took the Confederates unaware, but before sunup pickets alerted Ewell that the Federals were across the river. Ewell in turn notified Lee at Petersburg about the impending attack. Lee immediately sent Maj. Gen. Charles Field’s division from Petersburg. Field’s men traveled by rail as far as possible and then marched across a pontoon bridge spanning the James. After Field set out, Lee dispatched Maj. Gen. Robert F. Hoke with more troops to follow him. Artillery commander Brig. Gen. Edward P. Alexander was ordered to bring as many guns as he could safely remove from other points and join Ewell. Lee also telegraphed Secretary of War James Seddon, asking him to call up the militia and local troops available in Richmond. Even with these reinforcements on the way, Ewell faced several more hours of stalling a greatly superior enemy force.

Affairs were serious enough as it was, but Ewell made a miscalculation that put the capital in even greater danger. If Ord decided to move up the bank of the James, he might take Signal Hill and come upon Chaffin’s Bluff from the south. At the bluff, a vital pontoon bridge linked the Confederates north of the river with those stationed around Petersburg. Unaware that the Federals were aiming for Fort Harrison, Ewell shuffled a large portion of his available force down to Signal Hill, two miles from the fort. Stannard’s division loomed before Fort Harrison. There was a real danger that the Federals could punch through the lightly held fort then roll up long stretches of the neighboring works by flank attacks or by circling from the rear. Richmond was in great peril.

Fort Harrison was an earthwork one mile east of Chaffin’s Bluff and two miles west of the works stormed by Paine’s division. The Confederates had named the fort after Lieutenant William Elzey Harrison, the engineer officer who started the original works on the site in 1862. Harrison laid out a line including 15 batteries. His original Batteries 7, 8 and 9 were enlarged and combined into what became Fort Harrison. To strengthen these works, which defended Richmond from the southeast and shielded the batteries overlooking the James River at Chaffin’s Bluff, a new system of strongholds went up behind Fort Harrison. To the north were the neighboring smaller works of Forts Johnson, Gregg, and Gilmer. One mile to the southeast was another, larger work called Fort Hoke. Work had just started on more entrenchments that would stretch down to Signal Hill.

Assault on Fort Harrison

Stannard, receiving a message from Burnham that he was in front of the Rebel works, ordered an immediate attack. Fort Harrison presented a formidable appearance, but with hundreds of its men out of the way at Signal Hill, the fort and the surrounding works were defended by only 800 troops. Major Richard C. Taylor of Maury’s artillery battalion found himself in command of the beleaguered stronghold. He had nine guns inside the fort; the others were in adjoining works. A mere four guns in the fort were operable, as the others had been spiked or were out of repair. Only three dozen gunners in Lieutenant John Guerrand’s Goochland Artillery were on hand to service them.

Burnham’s men left the Varina Road and stepped onto a plowed field. They covered 1,400 yards across the field while exposed to a plunging artillery fire that was, one soldier reported, “galling in the extreme.” Burnham’s men halted at the base of the slope in front of the Rebel works. Spotting Confederate reinforcements moving in from his right (possibly some of the men driven out of the New Market Heights line), Stannard ordered an immediate charge. His troops poured over the parapet and placed their flag on Fort Harrison. Captain Cecil Clay of the 58th Pennsylvania was one of the Federals charging into Fort Harrison. A Confederate knocked down Clay’s first sergeant with a fuse hammer, a wooden mallet used by gunners to drive fuses into shells. The sergeant angrily jumped to his feet and exclaimed, “Damn a man who would use anything like that for a weapon!”

Inside the fort the Confederate defense disintegrated. Among the 50 men taken prisoner were Major Taylor and Lt. Col. John Minor Maury, who had arrived at the scene too late to affect the outcome of the surprise attack. Many others fled, although some held on until the last second. Private Rock of the Goochland Artillery remembered Taylor ordering them to cram a double load into one of the fort’s Columbiads for a final devastating shot at the enemy. Colonel John M. Hughs of the 25th Tennessee had commanded some of the pickets who were driven in by Stannard’s Spencer repeaters. As the Federals swept toward the walls, he rode his horse out over the drawbridge that crossed the exterior ditch at the north end of the fort. Hughs emptied his revolver at the approaching Yankees, rode back into the fort, and escaped.

By 7 am, Fort Harrison was in Union hands. Brief and inefficient though the Confederate resistance was, Stannard’s division still suffered 500 casualties before the fort fell. The few guns captured in working order were dragged around to fire on the retreating Rebels. Burnham pitched in to help aim one of the captured pieces. While at the gun he was struck down by a musket ball and died within moments.

Confederate Naval Support Arrives

About this time Ewell rode onto the scene ahead of the first reinforcements. Corporal Charles Johnston of the Salem Artillery remembered the general’s desperate efforts to halt the Confederate rout. Ewell, said Johnston, “was with the skirmish line, constantly encouraging them by his presence and coolness. I remember very distinctly how he looked, mounted on an old gray horse, as mad as he could be, shouting to the men, and seeming to be everywhere at once.” The ground just west of Fort Harrison was covered with woods, and Ewell scraped together a handful of men. Soldiers, stragglers, and teamsters made a noisy show of firing at the Union soldiers in the fort.

Union attention shifted south to the trenches running down to the James. Ord could only assemble a small attacking party of skirmishers and officers. Leading the assault himself, Ord drove the scattered Confederate defenders out of the breastworks to Fort Hoke. The main force there was Captain Cornelius Allen’s Lunenburg Heavy Artillery. Joined by stray infantrymen and reservists, they repelled the Union advance. Ord fell, badly wounded in the leg. With a tourniquet applied to stop the bleeding, he stayed in command until a surgeon demanded that he leave the front. Ord turned over command to Brig. Gen. Charles A. Heckman.

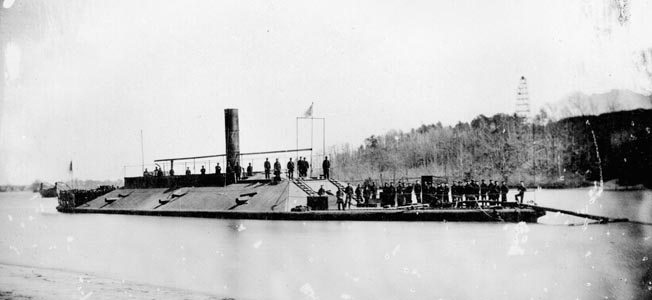

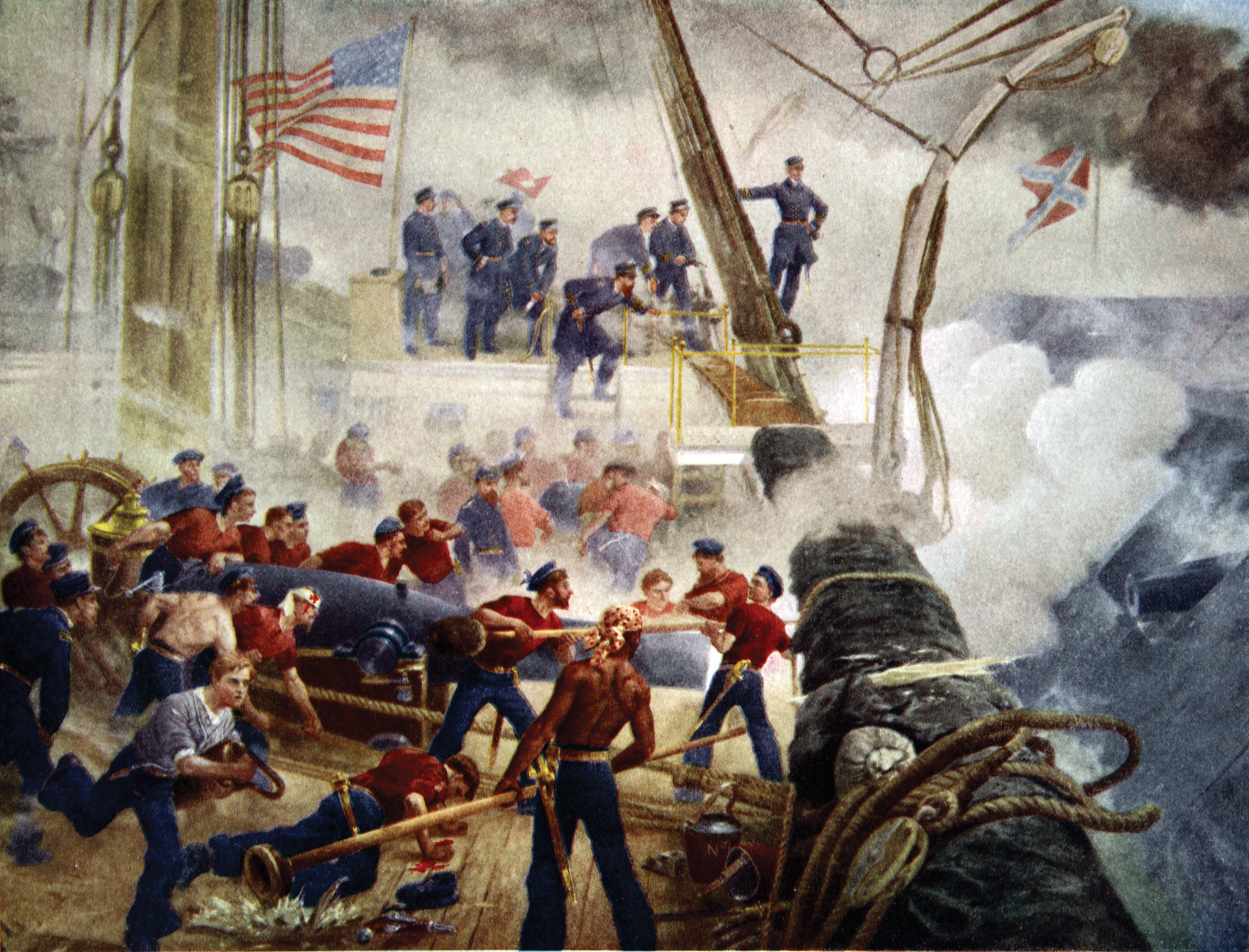

Ewell’s first substantial help came from the Confederate Navy’s James River Squadron. By 8 am, a naval battery commander notified Commander Thomas R. Rootes about the Union attacks. Rootes immediately ordered the gunboats Nansemond and Drewry to Chaffin’s Bluff and sent an officer ashore for further details. The officer returned with the news that Fort Harrison had fallen and a request for help from General Ewell. Rootes took the ironclads Fredericksburg and Richmond downriver to a landing somewhat ominously called the Graveyard, two miles south of the captured fort.

It was 10:10 am before the vessels were in position to open fire on the fort and the masses of Union troops around it. Rootes sent Lieutenant E.T. Eggleston of the Confederate Marine Corps ashore with a signal officer and an elevated observation stand to spot the fall of their shots against the enemy. Eggleston sent word that the shells were falling short, so Rootes had his guns aboard Fredericksburg and Richmond loaded with high charges. With the heavier charges, Eggleston saw the projectiles landing among the enemy troops around Fort Hoke. Ewell sent word to fire fast, and the ironclads kept up their fire all day, hurling more than 300 rounds from their big guns. Grateful army officers later thanked their naval comrades for their long-range assistance, which they believed helped slow the Union forces until Confederate reinforcements could arrive.

Heckman’s Advance

After taking over from Ord, Heckman launched a series of disjointed attacks on the Confederate positions north of Fort Harrison. The 2nd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery was ordered to take a small work called Fort Johnston. Private Joseph M. Alexander remembered that the Pennsylvania regiment passed the ambulance carrying General Ord, who cheered on the men, telling them, “Hurry up, boys! We’ll be in Richmond tonight.”

Alexander’s regiment hurried forward, followed by the 89th New York. Out in the open, they attracted cannon fire from the Confederate works while big shells soaring down from the James River gunboats crashed among them. In the lead, a battalion of the Pennsylvanians under Major James L. Anderson drew ahead while heavy Confederate fire drove the rest of his regiment and the New Yorkers back to take cover.

Anderson’s head was shot off when he was 100 yards away from the fort. In his pocket was a newly signed commission as colonel of the regiment. So heavy was the fall of incoming shells that Alexander saw comrades injured by splinters flying off their shattered musket stocks. From a wounded Pennsylvanian who made it back to their lines, a surgeon removed a musket mainspring that had been driven into the soldier’s chest. Anderson’s battalion was trapped and cut off under the enemy lines while the supporting troops were driven back. Most of his battalion was killed or taken prisoner.

The sounds of battle carried clearly to Richmond. John Beauchamp Jones, a clerk at the War Department, heard a “heavy and brisk cannonading” as he walked to his office. As he worked at his desk that morning, “the vibrations were very perceptible.” After lunch, news reached the city that Fort Harrison had fallen and the Yankees were moving toward town. Businesses and government offices closed. Scores of exempted workers joined their militia companies and marched toward the battle. Jones noted that squads of guards were sent into the streets everywhere with orders to arrest every able-bodied man they met, regardless of papers, to throw against the enemy. Citizens watched anxiously from hills and tall buildings, peering at the smoke rising from the battlefield.

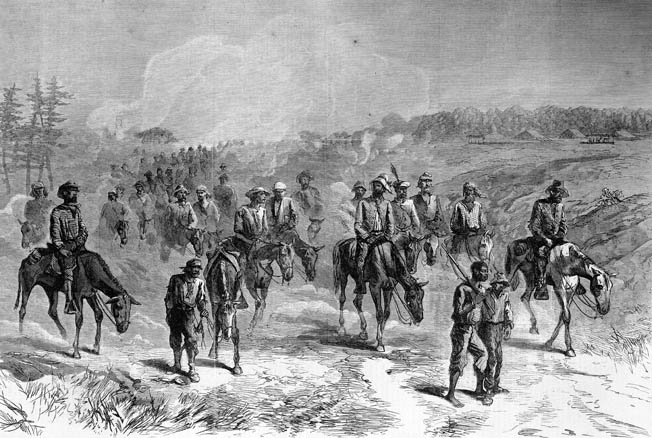

The initial fear in Richmond was due to Kautz, who had slipped very close to the city. After the New Market Road line fell to X Corps, he took his cavalry through and reached the Darbytown Road. They pushed along the lightly defended road and by 10 am were poised only two miles from the edge of Richmond. A hastily gathered force, Major James Hensley’s 10th Virginia Heavy Artillery Battalion, blocked the road with six guns and 100 men. Surprised by Hensley’s resistance and uncertain about what else lay ahead, Kautz withdrew. Three hours later he made another rush at Richmond farther north on the Charles City Road. Again, a scratch force faced them from behind a thin line of entrenchments and a few cannon. Again, Kautz’s caution won out, and he pulled away. After a bungled night attack on another Confederate position, he rode back to rejoin the main Union force the next morning.

By late morning, Heckman’s advance had stalled. He had suffered heavy losses for very little gain. General Grant personally rode to the battlefield to check on the progress of the operations, although he interfered little with the planning of the day’s fighting. Confederate reinforcements trickled in from Richmond and elsewhere. The Southerners anchored their new defense at Fort Gilmer. Named for Maj. Gen. Jeremy Francis Gilmer, the chief engineer of the Confederate Army, it was a smaller work than Fort Harrison, but it was fronted by a formidable, 27-foot-deep ditch. This daunting obstacle to an infantry attack was designed to prevent Union engineers from digging under the works. Set on high ground, the fort looked down on an open expanse where for some distance trees had been cut down and left with their branches attached to create more obstacles.

“Death Fairly Reveled in That Ravine”

Elements of X Corps marched from New Market Heights to join the attack on the main Confederate lines. After marching to the pontoon bridge the night before and taking part in the day’s action, they were already worn out. Two divisions of the corps made for Fort Gilmer. Maj. Gen. Robert Foster’s division moved south from the New Market Road toward the north face of the fort, hindered by having to cross the low, brush-tangled tributaries of Cornelius Creek. Pulling themselves out of the nearest ravine to the entrenchments, the Federals stepped into a cornfield. Now within easy range of Confederate guns, Foster’s ranks were cut down by intense artillery fire aided by a growing number of Rebel infantrymen filing into the works. Those who survived got no closer to Fort Gilmer and took cover in the ravine.

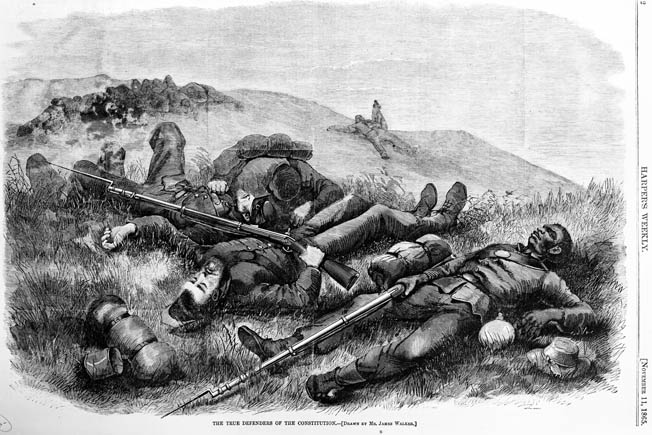

Birney’s older brother, Brig Gen. William Birney, led his brigade of African American troops toward the fort. Sent in one at a time, each successive regiment was cut to pieces. By a tragic misunderstanding of orders, only four companies of the 7th USCT were hurled at the fort. One-third of the 189 men were shot down before they approached the works, but the remainder made it to the deep ditch before the ramparts. Some tried to boost other men up onto their shoulders to climb over the parapet, but musket fire hit anyone who looked over the edge. Adding to the musketry, the defenders improvised 12-pounder grenades. Cutting artillery fuses to a two-second length, they lit them and rolled the shells over the parapet into the ditch onto the attackers. Only one man of the four companies made it back to the Union lines; the rest were either killed or captured. “Death fairly reveled in that ravine,” one New York soldier remembered.

Counterattack on Fort Harrison

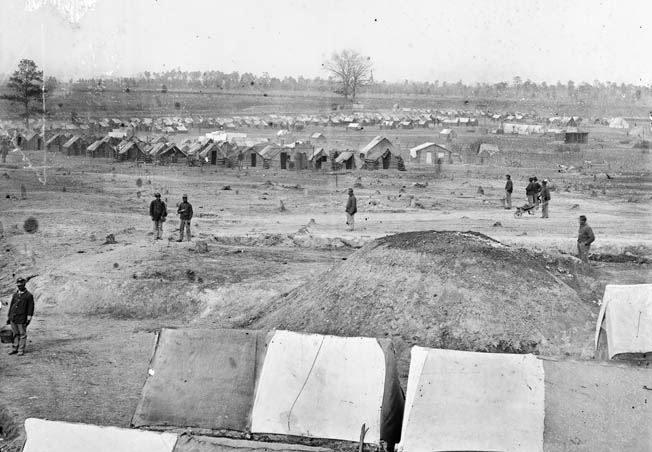

That afternoon and on into the night the Union forces held their gains and prepared to defend them against the counterattacks that they expected would come the next day. Fort Harrison had been built with some barracks on its western side but no defensive wall. Now the new occupants tore down the barracks and threw up a new defensive face to block Confederate attacks. Cecil Clay remembered, “Everybody worked with such tools or apologies for tools as could be had and a sort of rifle-pit was constructed across the rear or open space of Fort Harrison.”

Lee judged the fighting at Fort Harrison even more serious than the threat to Petersburg. Coming to Chaffin’s Bluff in person, he planned to take back the captured fort. He considered a night attack, using the first brigades of reinforcements, but decided that waiting for daylight and the arrival of more troops promised better success. On the morning of September 30, as Lee massed his troops to attempt the recapture of Fort Harrison, Richmond’s citizens waited for news of the peril looming to the east of them. Of the city’s newspapers, only the Richmond Whig managed to get out an edition, as nearly all of the city’s printers were now carrying muskets at the front. Exemption papers were no more valid that they had been on the day before. Numerous male civilians were detained and sent to the fighting. Overzealously following their orders, guards temporarily arrested one-third of President Davis’ cabinet: Postmaster General John H. Reagan and Attorney General George Davis.

Confederate ironclads in the James reopened their fire in the morning. Elevation of the naval guns was limited to only six to seven degrees, which restricted their range. To reach the enemy, the guns required charges exceeding those spelled out in naval regulations. With the extra-large doses of powder, a 7-inch rifle gun aboard Fredericksburg exploded on its third shot of the day. Lee could not accept a Union force lodged within the Richmond defenses. He was confident that his troops could clear the enemy out. Alexander’s artillery would soften up the fort. Then Field and Hoke would send in their infantry, hitting simultaneously from two directions. Hoke foresaw only a costly disaster, and he vainly tried to persuade Lee to wait behind a strong new line of fortifications and draw the Federals out in the open to attack them.

Alexander asked Hoke where he would like the artillery placed before the attack. Hoke replied he would rather Alexander not fire a shot at all. The bombardment was likelier, thought Hoke, “to demoralize my men by your shells falling short and bursting among my men” than to hurt the enemy. Artillery would only help “if you will bring your guns up to my line and charge with my men.” Alexander replied that such a move would get his horses killed. “Yes,” answered Hoke, “and my men are going to be killed. Are your horses of more value than the lives of my soldiers?”

Hoke’s objections were for naught, and the bombardment began. Lee’s plan called for Hoke, with five brigades, to attack the new western façade of Fort Harrison. Field would bring his three brigades from the east and attack the original front of the fort. His troops would wait in a ravine until Hoke was in position, then both forces would attack at the same time. The Confederate plans fell apart quickly. Brig. Gen. George “Tige” Anderson’s Georgian brigade of Field’s division impetuously poured out of the ravine and charged Fort Harrison. Rushing ahead of any support, the brigade was wrecked in the futile charge. Brig. Gen. John Bratton of South Carolina, whose brigade was to follow 100 yards in the rear of Anderson, felt obligated to support the Georgians and sent his own men against the fort. As Anderson’s men reeled back, one of Bratton’s regiments captured a small redan. While it had no major effect on the battle, the capture of the redan distracted the Federals and enabled some of the Confederates to escape.

Field’s third and last brigade, that of Colonel Pinckney D. Bowles of Alabama, also charged and was driven back with heavy losses. Hoke’s attacks began too late, after Field’s forces were broken up by the heavy Union fire. Hoke’s first attack was broken up and repelled, largely from the concentrated fire of the Federals’ seven-shot Spencers. Private Alexander of the 2nd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery talked to a wounded North Carolina prisoner after the battle. Thinking of the firepower of the repeating rifles, the Rebel said, “You’uns did not seem to load your guns.”

With Lee’s personal urging, two more attacks by Hoke followed, but they were unable to dislodge the Union troops from Fort Harrison. Most of the Confederate casualties of the battle occurred on the second day during these charges. A survivor of Clingman’s brigade, then commanded by Colonel Hector McKethan, wrote that the brigade charged Fort Harrison with 857 men and lost 587 of them in 10 to 15 minutes. The 8th North Carolina went into the battle with 175 officers and men. Only about 25 were able to report for duty the next morning. The regiment’s battle flag was gone. Trapped under hopelessly heavy Union fire, the color bearer tore the banner to tiny shreds so it would not be captured with him. One of Hoke’s men, echoing his commander’s earlier complaint, bitterly wrote, “The dead were buried under the flag of truce, but the artillery horses were saved.” Fighting around Fort Harrison ended about 4 pm on September 29. Butler’s army had suffered about 3,300 casualties among its 20,000 men. The Confederates, who eventually threw about 16,000 into the battles, lost 2,000 men.

Aftermath of Grant’s Fifth Offensive

While Field and Hoke made their attacks on September 30, Meade charged the Confederate entrenchments southwest of Petersburg. They captured a section of works around a redoubt called Fort Archer. Under Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill, Confederates dug new fortifications and repelled the Union forces from further progress. Fighting continued until October 2, when each side settled into their newly established lines of entrenchment. Another 2,800 Union and 1,300 Confederate casualties were added to the cost of Grant’s fifth offensive.

Fourteen men from Draper’s brigade and other USCT regiments in the Army of the James received Medals of Honor for their actions on September 29. Butler was so impressed with the conduct of his USCT regiments at New Market Heights that he supplemented the Medal of Honor awards with a citation of his own, known as the Army of the James Medal or the Butler Medal. Butler himself ordered and paid for the specially designed medals and ribbons. They were manufactured by Tiffany & Company and modeled on the Crimean War Medals issued by Great Britain. “I record with pride,” wrote Butler, “that in that single action there were so many deserving that it called for a presentation of nearly two hundred.” The Army of the James Medal was the only military honor created for a specific battle during the Civil War.

The End of the Confederacy

The fifth major offensive by Grant against the Richmond-Petersburg defenses was part failure and part success. The Confederate capital and its satellite stronghold, Petersburg, were still in Confederate hands. But Union gains forced the Confederates to further stretch and distort their defensive lines and spread their troops ever thinner. The Federals, in turn, strengthened the captured Fort Harrison, renaming it Fort Burnham after the Maine general who was killed there. South and north of the fort, Union engineers dug new entrenchments with abatis facing the Confederates on the west. Additional Union works were built and anchored on the James River at newly constructed Fort Brady, where heavy guns kept the Confederates’ James River Squadron bottled up higher in the river.

The Confederates abandoned the segments of the old line that were now covered by Fort Burnham and consolidated a new line of works that served as a sort of scar tissue to contain the sore spot of Fort Harrison. To make up for the lack of soldiers to man the new lines, they planted hundreds of “subterranean shells” supplied by the navy’s Torpedo Bureau in front of their works. Red warning flags, planted three feet behind the mines to warn off their own men, would be removed in the event of a Union assault.

As the dust settled from the loss of Fort Harrison and the failure of the desperate effort to recapture it, the seriousness of the South’s deteriorating military situation became all too clear. Lee wrote Secretary of War James Seddon on October 4 from his headquarters at Chaffin’s Farm. Unless substantial numbers of new soldiers could be found by a heavy call-up of exempted men, he warned, “It will be very difficult for us to maintain ourselves.” Without reinforcing the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee said, the government faced the dreaded prospect of “the discouragement of our people that would follow the fall of Richmond.” Lee’s grim premonition would come to pass seven months later. Butler’s attacks north of the James on September 29 and 30 were an important link in the parlous chain of events that ultimately led to the final collapse of the Petersburg lines, the evacuation of Richmond, and the end of the Confederacy.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments