By Al Hemingway

At the start of the Battle of Mortain, Field Marshal Gunther Von Kluge was in an optimistic mood. He had recently been placed in command of all German troops in western France. In addition, he had taken command of Army Group B after Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was wounded when his staff car was pelted with machine-gun fire from several Royal Air Force Hawker Typhoon fighters that July 1944.

Von Kluge had planned to move his forces back and establish a defensive barrier nearer the German border; however, Adolf Hitler had other ideas. In early August, the Führer sent a message to Von Kluge authorizing him to move against the Allied armies at Avranches. “We must strike like lightning,” Hitler wrote. “When we reach the sea, the American spearheads will be cut off.” Hitler dubbed his audacious scheme Operation Luttich, named after the Belgian city where the German Army had won a decisive battle in World War I.

Although the plan called for eight full-strength panzer divisions, Von Kluge knew many of his units were woefully undermanned. Nonetheless, the units he managed to assemble were still a viable force to contend with; as one German officer said, they were “the best German armored divisions.”

Impressive Array Of German Armored Vehicles

They included the 1st SS Panzer (Liebstandarte Adolf Hitler) Division, the 2nd SS Panzer (Das Reich) Division, with the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division attached, and the 2nd and 116th Panzer Divisions—all these armored units were organized into the newly formed XLVII Corps led by General Hans Freiherr Funck. Although Funck had less than 200 tanks, they were formidable. Nearly half were the Mark IV, while the remainder were the heavier Mark V Panthers. Both types were armed with 75mm guns and were extremely mobile and very dependable. In addition, the German corps possessed a few of the slow-moving but fearsome 55-ton Tiger tanks. Also in the assault arsenal were hundreds of half-tracks, assault guns, armored cars, and flak guns.

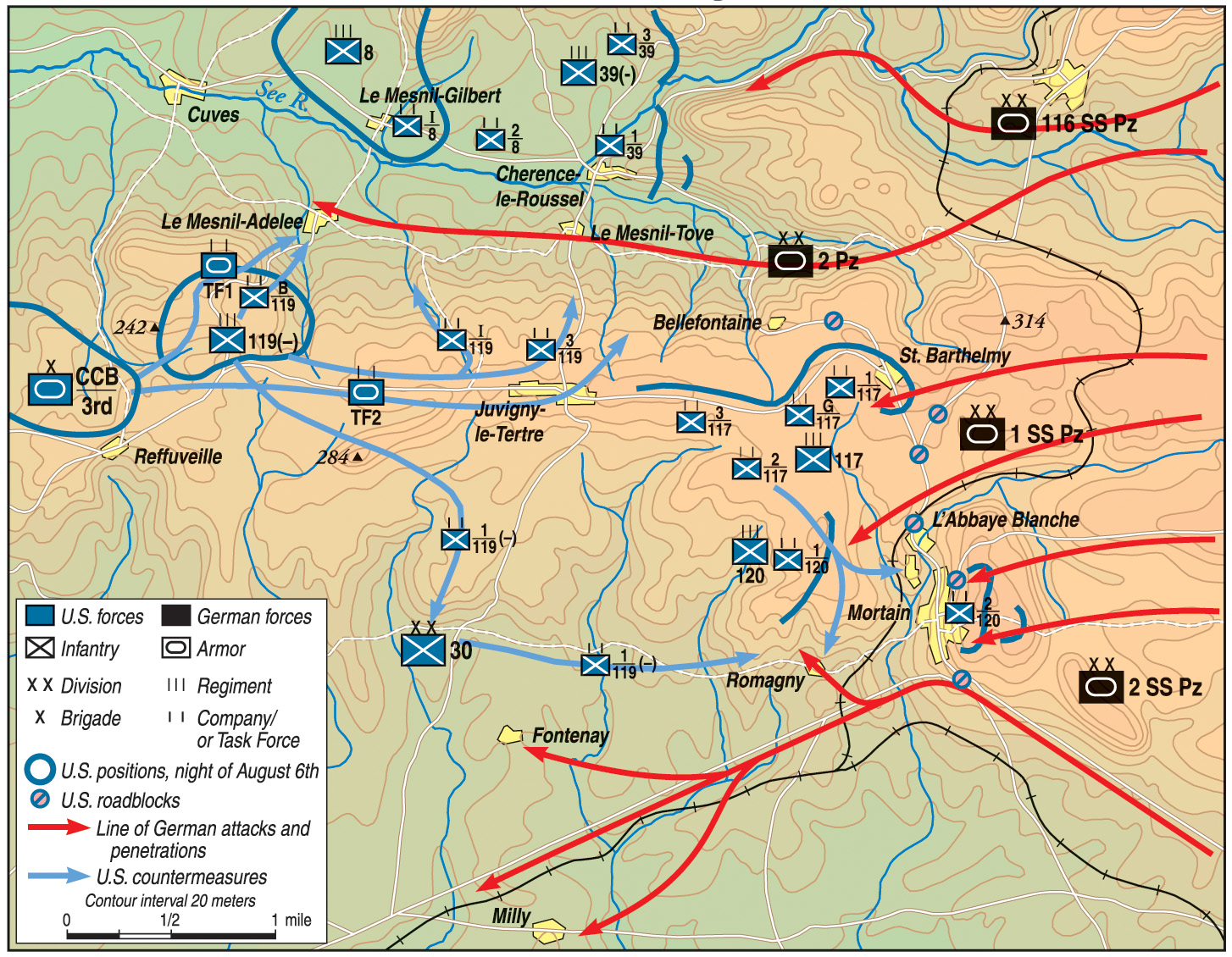

Operation Luttich was to be launched on Sunday, August 6, at 2200 hours. The 2nd Panzer Division, together with part of the 1st SS Panzers and 116th Panzers, would drive toward the center following the southern bank of the See River to St. Barthelmy. On the right, elements of the 2nd Panzers and the remainder of the 116th Panzers would proceed to the northern bank of the See River. To the left, the 2nd SS Panzers would spearhead the drive toward Mortain, seizing the high ground and moving on to St. Hilaire. As the German units captured the St. Barthelmy-Juvigny roadway, the rest of the 1st SS Panzers would move with lightning speed toward the final objective—Avranches.

Hitler was ecstatic about the plan. He wrote to Von Kluge: “The decision in the Battle of France depends on the success of the attack. The Commander-in-Chief West has a unique opportunity, which will never return, to drive into an exposed area and thereby to change the situation entirely.”

If Hitler was excited about the operation, Von Kluge was not. To make matters even worse, he was informed by Col. Gen. Alfred Jodl, Hitler’s operations officer, that there was to be a command change. The Führer did not think General Funck was forceful enough, and decided to replace him with General Heinrich Eberbach. Hitler also promised 140 Panther and Mark IV tanks to Von Kluge. Unfortunately, the armor would not reach him for at least 24 hours.

Von Kluge pleaded against any changes at this point in the operation, whose launch was a mere nine hours away. Although the additional tanks would be most welcome, he felt the element of surprise was imperative. After much discussion, Hitler acquiesced; however, his command change remained. Von Kluge had won half the argument at least.

During the first week of August, the Third Army, under the leadership of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, moved to the right of the First Army. While this movement was under way, the British seized the area between the Vire and Orne Rivers in an effort to keep the pressure on the Germans’ right flank.

In late July a plan was devised to attack along the St. Lô-Périers Highway. Named Operation Cobra, the scheme called for units to cut through the German defenses before they could regroup and counterattack. To accomplish this breakthrough, the U.S. VII Corps, consisting of the 1st, 4th, 9th, and 30th Infantry Divisions and the 3rd Armored Division, was called upon to get the job done.

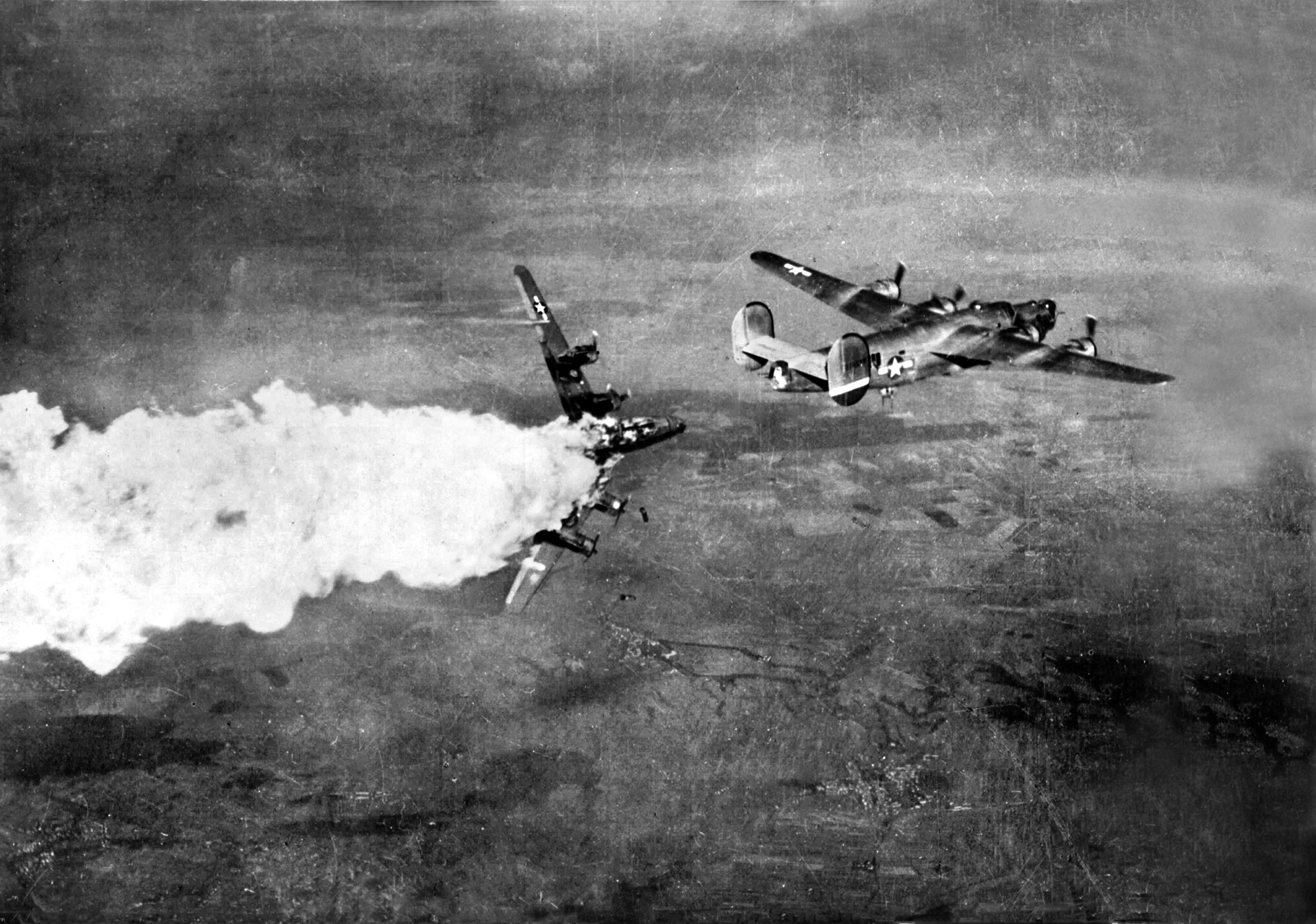

On July 24, bombers inadvertently let loose their load on soldiers of the 120th Infantry Regiment, part of the 30th Division. This unfortunate mishap killed 25 men and wounded 131. But the worst was yet to come. The next morning the bombers returned. The first bombs were accurate, falling on German units. Then things took a turn for the worse.

In his book, Battle for Mortain: The 30th Infantry Division Saves the Breakout, August 7-12, 1944, author Alwyn Featherston recounts the horrific events. “Lieutenant Murray Pulver was standing in a small apple orchard with two of his sergeants, watching the bombs fall on German positions when ‘those whistling bombs suddenly sounded different to me. I looked up to see that a wave of planes had released too soon…. We dove into a shallow slit trench. The earth trembled and shook. We were covered with dirt, and the dust and the acrid smell of burnt powder choked us. The terror seemed to go on for hours, but actually it ended within a few minutes. We dug our way out of the hole to find everything quiet…. The stillness was weird. There wasn’t an apple left among the trees still standing, nor were there many leaves. I could not believe we were still alive.’”

Others were not so lucky. In all, 111 men were lost. Nearly 500 were wounded. Among the dead was Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair, head of the First Army Group. He was later identified by his rank insignia, the three stars he wore, because his body was “mangled beyond recognition.” Soldiers in the 119th and 120th Regiments of the 30th Division bore the brunt of the friendly fire casualties. Sixty-four Americans were killed, 374 wounded, and 60 listed as missing.

In spite of this terrible accident, the assault jumped off with soldiers driving a wedge deep within German defenses. The 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry Regiment made remarkable progress against stiff enemy resistance. Maj. Gen. J. Lawton “Lightning Joe” Collins sent his armored units past the foot soldiers as the vanguard of the attack. By nightfall the Americans held a vital road junction near Le Mesnil-Herman. General Omar Bradley, commander of the U.S. XII Army Group, was overjoyed and wrote Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Things on our front look really good…. We believe we have the Germans out of the ditches and in complete demoralization and expect to take full advantage of them.”

To take advantage of the breakout, units moved toward the Vire River. Soon, fierce fighting around the small village of Tessy-sur-Vire increased. The 30th Division, also known as the “Old Hickory” Division, spearheaded the drive. The unit was nicknamed in honor of the flamboyant General Andrew Jackson, soldier and later president of the United States.

“The Big Red One”

The 30th Infantry Division’s advance was halted on July 28 with the units incurring heavy losses. What Maj. Gen. Leland Hobbs, the division commander, did not realize was that his soldiers had just encountered the 2nd Panzer Division. Despite mounting casualties within his ranks, Hobbs ordered yet another attack on Tessy on August 1. Company B led the assault, which was soon met by enemy artillery fire that knocked men to the ground with its blasts. When the men of Company B reached the town itself, fighting was house to house. Assisted by armor, the forward movement went well until the tanks mistook U.S. infantrymen for German soldiers. When a white flag was waved, the armored units soon realized their mistake. Luckily, no friendly casualties resulted from this error and the town was taken by the Americans.

After the horrendous ordeals endured by the riflemen of the 30th Division, they were placed in reserve for a well-deserved rest. A few days later, the division was ordered to relieve elements of the 1st Infantry Division, or the “Big Red One,” at the town of Mortain—-an important area because of its high ground and roadways.

Mortain, a quaint village with a population of approximately 1,600, is situated near the Cance River. On the eastern side of the town is a spur called La Suisse Normande by the local inhabitants. To the men of the 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry Regiment it was known as Hill 314. The hill rose gradually from the north but more sharply on the east and south, while on the western side it possessed steep cliffs. From this vantage point one can see for miles if the weather cooperates; any attacking force would be spotted traveling any of the roadways. It was immediately apparent that Hill 314 should be occupied quickly, and it was obvious to Bradley that Mortain, and more specifically Hill 314, was strategically located.

On August 3, the 18th Infantry Regiment of the Big Red One had seized Mortain. In addition to securing Hill 314, they also held Hill 285, another key spot just northwest of Hill 314. Also, the intersection at L’Abbaye Blanche was in American hands. This junction was significant. One road traveled east toward the hamlet of Ger. The other thoroughfare went north to La Dainie where it split east toward Sourdeval and west toward the town of St. Barthelmy.

On August 6, the 117th Infantry Regiment of the 30th Division arrived at St. Barthelmy. As the Old Hickory riflemen relieved the 26th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division they were informed that the area had been peaceful since their arrival a few days earlier. The weary soldiers thought they were getting a well-earned respite from the war.

Colonel Hammond Birks, leader of the 120th Infantry Regiment, enjoyed the tranquility of the charming French village; one officer even commented that Mortain would be “an excellent place for a little rest and recreation.”

Securing Hill 314

The following day, columns from the 30th began streaming into Mortain. Lieutenant Colonel Eads Hardaway, commanding the 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry Regiment, ordered Company E, two platoons from Company G, elements from Company H, plus Company K from the 3rd Battalion to defend Hill 314. “The order to move had been executed so rapidly, it had been impossible for the regiment to secure maps of this area,” Lieutenant Ralph Kerley, Company E commander, later wrote. “However, the 2nd Battalion S-2 secured a few large scale maps from the 1st Battalion, 18th Infantry, scarcely enough for a company. These had been in use for several days and were crumpled and badly marked.”

As the 30th Division riflemen ascended the hill, they realized that their predecessors had not spent much time building defensive positions. But they had been assured that there was no enemy to their front. This was to be an easy assignment.

Company K, led by Lieutenant Joseph “Indian Joe” Reaser, manned the northern knob of Hill 314. Kerley’s Company E and a squad from Company H established a line in the center of the perimeter. On the southern sector, Lieutenant Ronald Woody’s Company G set up its positions and one platoon from his unit was sent to the western edge. In all, approximately 700 men now stood guard over Hill 314.

Meanwhile, at the bottom of the rise, Company F’s commander, Captain Reynold Erichson, dispatched his first platoon, under Lieutenant Tom Andrews, to defend the road junction at L’Abbaye Blanche. Several 57mm antitank guns, mortars, and machine guns added to the infantry’s firepower. Late that afternoon, four 3-inch guns from Company A of the 823rd Tank Destroyer (TD) Battalion arrived, adding additional punch to the arsenal. Lieutenant Thomas Springfield, platoon commander from the 823rd, put two of his weapons along the northern road leading from Mortain. The other pair of 3-inch rifles was concealed in shallow trenches along Route 177, which led to St. Barthelmy. Also, several guns from Company B, 823rd found their way to the roadblock.

By the early hours of the next morning, most of the positions had been occupied and secured by the Old Hickory Division. As the GIs rested and slept, the village of Mortain celebrated. Their town was now in American possession, free from Nazi tyranny. Miraculously, they had suffered no damage. That was soon to change.

In the wee hours of the morning of August 7, Sergeant John Whitsett, attached to Headquarters Company, 120th Infantry Regiment, was suddenly awakened by a young soldier informing him that his platoon commander wanted to talk to him. Whitsett was told by his lieutenant that the Germans were coming.

German Surprise Attack

Refusing to believe the inexperienced officer, the veteran sergeant decided to take a look for himself. Walking down the road, he heard some noise. He leaped atop a hedgerow to get a better view and saw German soldiers marching toward Mortain. The enemy saw him and began firing as he jumped off the hedgerow. He raced back to his area to inform his unit that the Germans were indeed coming.

To make matters worse, a dense, soupy fog had developed, encompassing the area around Mortain. Men had difficulty identifying their units, and some Americans were quickly captured. The enemy promptly seized a 57mm gun safeguarding the road south of Mortain, and two squads from Company K were taken into custody by the Germans as well.

Soon, the Deutschland Regiment of the 2nd SS Panzer Division broke through the American defenses. Panzergrenadiers were driving into Mortain from the south and southeast with tanks following them. To the north, the Der Führer Regiment of the 2nd Panzer was making headway toward Captain Erichson’s position at L’Abbaye Blanche. Elements of Company F, guarding the approach south of the village, felt the full onslaught of the German blitzkrieg. A small group of GIs managed to escape the enemy assault and traveled north to link up with Company F’s other roadblock defenses just north at L’Abbaye Blanche. The remaining stragglers climbed Hill 314 and joined Company E. Everyone else was either killed, wounded, or captured.

Shouting “Heil Hitler,” the enemy infantrymen assaulted Company G’s position on the hill. “The group’s attack was vicious and made enough noise that one could easily believe an entire battalion was attacking,” wrote Lieutenant Ralph Kerley. German armor sent shells crashing into the trees so that shrapnel and wood splinters rained down upon them. Company G lost over a hundred men before the company commander, Lieutenant Woody, consolidated his forces and ordered the survivors to withdraw to an open area 100 meters to the rear to reestablish a new perimeter.

Meanwhile, Colonel Hammond Birks, 120th Infantry commander, was in a quandary. His regimental command post (CP) was in a farmhouse just west of town. The 3rd Battalion, his regimental reserve, was taken from him (less Company K) and sent to Barenton to occupy the town. Just after 2 am, he was informed by the 2nd Battalion commander, Lt. Col. Hardaway, that enemy troops were advancing on Mortain in force. However, Birks was not about to give up that easily. He was a hard-charging officer. He was a mere 18 years old when he was a company commander in World War I and had remained in the Regular Army after the conflict was over. He was not about to lose his regiment to any German attack.

Birks ordered Company C off Hill 285 and ordered his men to retake Mortain and set up roadblocks south of the village. As the riflemen approached the hamlet, gunfire erupted. Soon the beleaguered company was in the thick of the fighting. Lieutenant Albert Smith, the company commander, was killed by a German 88mm round. The combat was even more terrifying in the darkness and the fog. It was a surrealistic atmosphere. Soldiers could not identify each other in the inky blackness. The only illumination was from the town structures set ablaze by the shelling.

Amid the confusion, Corporal Dudley Wilkerson loaded a bazooka and sent a round crashing into a German tank. His victory was short-lived, however, when an enemy artillery shell slammed into the building he was hiding behind. The concussion knocked him to the ground. Wilkerson continued fighting until a German concussion grenade exploded near him. His men moved him to the basement of one of the shattered buildings in town, where he quickly passed out. “When I woke up,” he later said, “there was a cage of rabbits right in front of me. I thought I was in heaven.”

As dawn broke over the battlefield, the 30th Infantry had miraculously held most of Hill 314. A thick fog still gripped the landscape. Several squads of German infantry had made some gains on the western and southern faces of the hill. Company G mounted a counterattack to clear the enemy from their positions. The fighting was close-in and bitter. Hand-to-hand combat ensued.

In the end, Woody’s men were victorious in driving the Germans from their foxholes and back down the incline. The Americans once again had Hill 314 to themselves. How long they could hold on was unknown. They could not communicate with the battalion CP. They did have radio contact with Birks’ headquarters, but he could not do much for his besieged troops; his only reserve, Company C, was engaging the enemy in Mortain itself.

Elsewhere, the combat had been a mixed bag. To the north, the 39th Infantry Regiment did stop the advance of the German 84th Division. The 117th was in close combat with the 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Regiment. The 117th’s regimental recon platoon was dispatched to seize the town of Romagny. Racing toward the village, the unit was ambushed. There were only a few survivors.

Beginner’s Luck With Bazooka

Company C tried valiantly to secure Mortain but was beaten back by overwhelming forces. The remainder of the company withdrew to the Regimental Tactical Operations Center (TOC). Here, they took up positions. Everyone fought, including clerks and communications personnel. Private 1st Class Joseph Shipley, the telephone switchboard operator, knocked out two German tanks with a bazooka. Ironically, the young soldier had never operated the weapon before.

Hardaway’s 2nd Battalion, TOC, was also overrun. He and his staff escaped and attempted to make their way to Hill 314. Unfortunately, intense enemy fire thwarted their efforts. Taking refuge in a shell-pocked building, Hardaway radioed Birks to tell him of his predicament. With his batteries getting weaker, he kept his radio transmissions short and did not disclose his location for fear of being captured.

By 8 am, the terrible fog that had been such a nuisance was beginning to dissipate. From their positions atop Hill 314, the riflemen could observe enemy troops and armor rolling into Mortain from the southeast and east. “Whether the enemy was ignorant of the fact that Hill 314 was occupied, or had simply chosen to ignore it, is not known and really doesn’t matter,” wrote Kerley. “His closed formations made a definite target for our artillery.”

Fortunately, a forward observer (FO) team headed by 1st Lt. Charles Bates and 2nd Lt. Robert Weiss called in fire from the 230th Field Artillery Battalion. The infantrymen placed the artillery observers in a key location, aware that their communications with gunners to the rear might hold the key to their survival. A steady fire by the American artillery took on the clustered German tanks in the town.

Later that morning, German artillery and mortar rounds pounded the men defending Hill 314. Companies E and K were particularly hard hit. German armor units, with infantry in tow, tried to make gains upon the hill. Once again, the FOs atop Hill 314 radioed in artillery barrages upon the advancing enemy formations. The bulk of the attack had been repelled, but not before the grenadiers had broken through and initiated a severe firefight with Ralph Kerley’s Company E. The German riflemen were soon repulsed, but Kerley’s men had suffered severely. His casualties were beginning to increase, and, with little or no medical supplies, the situation was worsening.

Later that afternoon, German soldiers from the Goetz von Berlichingen Division moved up to seize a portion of Hill 314. Pushing from the west, they ran headlong into Woody’s Company G. A pair of 60mm mortars kept the pressure on the enemy as the soldiers poured rifle and machine-gun fire into the enemy ranks. The weary infantrymen, who had been fighting for 36 straight hours, still managed to resist the enemy attack.

As the riflemen continued to hold out on Hill 314, Colonel Birks was busy trying to reopen roads and reinforce his men on the hilltop. The 1st Battalion, 119th Infantry, supported by a tank company, tried desperately to retake Romagny. A pitched battle was fought in the town, ending in a stalemate. The men of the 2nd Battalion, 117th Regiment were pushing toward Mortain. They were soon joined by the remnants of Company C, which had fought in the town the first night.

As darkness fell, the guns became silent in and around Mortain. That silence was soon shattered when the Germans tried once again to seize Hill 285 at 1:30 am on August 8. That hill had seen its share of fighting on the previous day. The attackers wedged themselves between Company A, 1st Battalion, 120th Infantry and a TD platoon. Lieutenant Francis Connors reorganized his men and successfully pushed the enemy back.

Hard fighting continued nonstop throughout the day. Gains were minimal. The 1st Battalion, 119th Infantry was stuck at Romagny. The 2nd Battalion, 117th Infantry was still trying to enter Mortain to relieve the defenders on Hill 314. However, the infantrymen on Hills 285 and 314 were still holding their positions despite being low on ammunition, medical supplies, and food. Also, despite the German assaults, the roadblocks at L’Abbaye Blanche were still secured.

On August 9, the third day of the battle, the Old Hickory riflemen on Hill 314 were in a near hopeless predicament. “The first gnawing pains of hunger and thirst were appearing,” wrote Kerley. “The ammunition supply had dwindled to practically nothing. Several of the severely wounded died during the night. The bodies of the dead, both our own and the enemy, were deteriorating fast in the warm August sun, and the stench on the hill was nauseating.” The men had found an apple orchard on the southern face of the hill and collected as many of the small green fruits as they could. In addition, they obtained cabbages and potatoes from an abandoned farm nearby.

Meanwhile, General Patton ordered his 35th Infantry Division toward Mortain to assist in the fighting there. Also, tanks from the 3rd Armored Division were moving north of the village to aid the troops engaging the Germans in that area.

With the men on Hill 314 in dire straits, it was decided to attempt an airdrop to get much-needed supplies to them. At first, several of the division’s artillery-spotter planes were utilized for the mission; however, when the slow-moving aircraft approached the drop zone, German antiaircraft fire peppered the tiny planes with shrapnel, downing one of them and causing the pilot to be captured.

That evening, an SS officer neared the American lines with a white flag. The German, who spoke impeccable English, informed a platoon commander of Company E that their “situation was hopeless.” He continued, saying that several in the battalion command group had been captured and it would be “no disgrace to surrender.” He further stated that if the Americans refused his generous surrender terms, they would be “blown to bits.” They had until 2000 hours to respond to the surrender offer.

The platoon commander hastily relayed the officer’s message to Lieutenant Kerley. A hard-drinking, profane man, Kerley wasted no time in giving his response. Although the answer is not known, the Company E commander later wrote that it was “short, to the point, and very unprintable!”

Just past 8 pm, the German 17th Panzergrenadier Division wasted no time in hitting Company E’s section of the perimeter. Kerley called an artillery strike right on top of his own position to break the back of the enemy assault. The big guns pounded the hill as U.S. soldiers found any available shelter to escape the screeching, white-hot shrapnel whistling through the air. For five minutes, 84 howitzers let loose a deafening barrage upon the Germans. Unable to withstand the onslaught, the grenadiers raced down the hill and retreated.

Despair Turns Into Anger And Resolve

This action had profound consequences upon the riflemen on Hill 314. Alwyn Featherston wrote regarding the Battle of Mortain: “Despair had been replaced by anger—and resolve. Kerley noticed the transformation but could not explain it. His men were still without food and medical supplies, were shorter on ammunition than ever before, and were totally dependent on a handful of dying radio batteries.”

On the following morning, August 10, the fourth day of the battle, another effort to resupply the hill was made using C-47s. A group of fighter aircraft bombed and strafed enemy positions near the hill. Later that day, the fighter planes returned escorting the C-47s. Although half of the load parachuted behind enemy lines, the infantrymen on the hill had received some food, ammunition, radio batteries, and some medical supplies.

To further assist the battalion on Hill 314, Lt. Col. Lewis Vieman, commanding officer of the 230th Field Artillery Battalion, had his men remove the smoke canisters and base-ejection charges of 10 105mm smoke shells. They proceeded to fill these rounds with bandages, dressings, morphine, and plasma. Then the projectiles were filled with sand, painted with a red stripe, and fired toward Hill 314. The mission had disappointing results. All of the shells filled with plasma were unusable due to the impact and concussion of the blast.

The fifth day of the battle saw the 1st Battalion, 119th Regiment and the 320th Regiment, together with the 737th Tank Battalion, making slow progress toward the Battle of Mortain. Both units were facing tough enemy opposition as they fought through harsh terrain that included miles of hedgerows.

However, toward the evening of August 11, enemy resistance around Hill 314 began to melt. Allied planes and artillery hammered enemy armor and infantry as they tried to make a hasty exit from the village. The screams and cries of the enemy could be heard from the German columns.

Sunday morning, August 12, dawned bright over the French countryside. As the relief troops cautiously inched their way through the shattered remains of the once picturesque town of Mortain, they met no organized enemy resistance. Only a few German snipers had remained behind to harass the Americans.

As the 120th Regiment’s commander, Colonel Birks, walked through the town, he was approached by half-dozen soldiers who hugged him. These individuals were the only survivors of the 2nd Battalion staff. Lt. Col. Hardaway was not among the group. His luck had run out, and he had been captured by the Germans a few days earlier.

Late that morning, lead elements from the 320th Infantry reached Company G’s lines on Hill 314. One of the soldiers walked up to Lieutenant Woody and asked for the company commander. Woody looked rough as he informed the man that he was the company commander. When he was told that they were being relieved, Woody shouted: “Alll—rright!”

The battle for Mortain and Hill 314 was finally over.

A World Of Burned Out Tanks

The 30th Infantry Division had sustained over 1,800 killed, wounded, and missing at Mortain. According to Kerley, “a total of 277 men were killed, wounded, captured and missing in action” while fighting on Hill 314.

However, the Germans had suffered far worse. Although the exact number of dead and wounded is not known, a dispatch from General Heinrich Eberbach, sent during the battle, mentions “the remnants of the 1st SS Panzer Division.” This message gives an indication of the horrendous casualties the Germans must have endured during Operation Luttich.

Burning armored vehicles and tanks littered the vicinity of Mortain. The situation was the same for other towns in the area as well. Entering the small hamlet of St. Barthelmy after the battle, Major Warren Giles, the 117th Infantry Regiment’s intelligence officer, was shocked. “That little town—and it was just a small town really—was totally destroyed,” he said. “I don’t know if there was anything left standing. There were Germans bodies everywhere. And tanks … a world of burnt out tanks.”

The 1st Battalion, 117th Infantry; 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry; Company K; 3rd Battalion, 120th Infantry; Companies A and B; 823rd TD Battalion; and the 1st and 2nd platoons from the 120th AT Company were all given the Presidential Unit Citation for their defense of the town and its outlying areas at the Battle of Mortain.

Many were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, including all the company commanders on Hill 314. “It would be impossible to record here the acts of self-sacrifice and personal bravery displayed by the men and officers of the battalion during this period,” wrote Kerley. “Some of the recommendations for awards were lost in the scramble to get moving, and were never awarded to those men to whom they were due.”

In the end, despite all the plans by the generals and their staffs, it was the “dogface” soldiers of the Old Hickory Division who prevailed. Through their determination and courage, they held Mortain against overwhelming odds by defeating four crack German divisions. They were indeed America’s best.

This is a flawed narrative. Why have a title with The Big Red One in it? They left the position before the battle. Accuracy matters.

Indeed it does. Ambrose’s book, Citizen Soldiers, calls it Hill 317. Once again I’m struck that officers get the medals, and nothing said of the NCO’s and grunts.