By Roy Morris Jr.

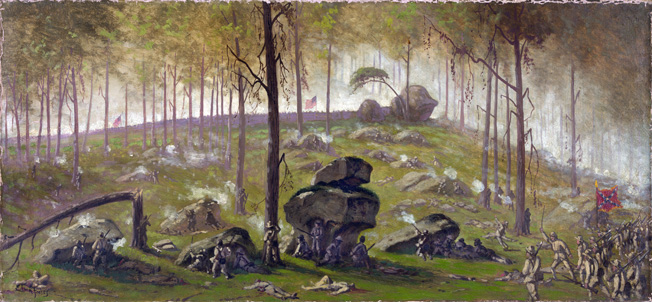

As they formed ranks on the Hanover Road one mile east of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on the afternoon of July 2, 1863, the men in the II Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia stared anxiously at the giant boulders and towering oak trees dotting the humpbacked prominence known as Culp’s Hill, three quarters of a mile southeast of town. The 630-foot hill, the highest ground in the vicinity, had long been a popular picnic site for Gettysburg residents. The trees gave welcome shade in summer, and the rocks served as handy seats and dining tables. Many a romance had begun on that hill.

On this day, however, there would be no picnics on Culp’s Hill. As the northernmost tip of the embattled Union Army’s four-mile-long, fishhook-shaped defensive line at Gettysburg, Culp’s Hill was a vital piece of military real estate. Its heights overlooked the eastern approach to the town, which had suddenly become the focus of the entire war effort in the east. If the Confederates could seize the hill, they could potentially roll up the entire Union line from north to south. The battle, and perhaps the war, could be won in a single day.

The day before, Robert E. Lee’s Confederates had stumbled into battle at Gettysburg before the general was ready or willing to engage. Lacking effective intelligence from his cavalry—Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart was off on another ill-advised ride around the Union rear—Lee’s advance force, under Maj. Gen. Henry Heth, had headed toward Gettysburg in search of shoes. (The always equipment-challenged graycoats had heard that there was a bulging shoe warehouse in the town.) Expecting to find only local militia and civilians on hand to oppose them, Heth’s men instead had run smack into an alert Union cavalry brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. John Buford. Soon, what began as a general skirmish had swelled into the largest battle of the war, as both sides funneled quick-arriving forces into line.

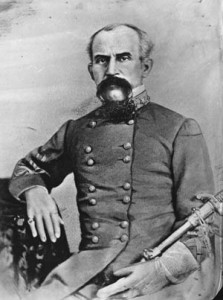

“Old Bald Head” at Gettysburg

Among the Confederate forces converging on Gettysburg was Lee’s II Corps, commanded now by Lt. Gen. Richard Stoddert Ewell in the wake of Lt. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s death at the Battle of Chancellorsville two months earlier. Ewell, whose army-wide reputation for eccentricity—if not necessarily his battlefield brilliance—rivaled that of his dead predecessor, seemed on paper a good choice to succeed Jackson. Ewell, like Jackson, was a native Virginian, a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, and a decorated hero in the Mexican War. He had successively commanded brigades, divisions, and corps in Lee’s army. But “Old Bald Head,” as Ewell was more or less affectionately known by his men, had only recently returned to duty after losing a leg at the Battle of Groveton. Wearing a cork artificial leg, he had to be strapped into the saddle and needed crutches to walk. The injury had not affected his voice, however. Ewell was still capable of spouting obscenities left and right in the heat of battle. His hyper-nervousness, prominent eyes, and wasted frame gave him the appearance of a spectral bird of prey.

Ewell’s men, at least initially, had performed well at Gettysburg, crashing into the Union XI Corps northeast of town and sending the Federals scampering ignominiously through the streets to the temporary safety of Cemetery Hill. But Ewell’s attack, like that of III Corps commander A.P. Hill west of Gettysburg, had bogged down by the late afternoon of July 1. Luck, in the form of Culp’s Hill and a scattering of other hills and ridges to the south, had allowed quick-thinking Union officers to cobble together a curving defensive line on the always crucial high ground. From Culp’s Hill to Cemetery Hill, Seminary Ridge, and Little and Big Round Tops, blue-clad defenders had moved into positions they would defend grimly and desperately for the next two days.

With his trained engineer’s eyes, Robert E. Lee could see the battle unfolding before him. Late in the afternoon on July 1, he sent Ewell a politely worded message urging him to attack Cemetery Hill, just west of Culp’s Hill, if Ewell felt that he “could do so to advantage.” This was as peremptory as Lee got; he habitually couched his orders in a courtly patrician politesse that left their recipients a great deal of wiggle room. It was a command style that depended greatly on the individuals receiving the commands. Had Stonewall Jackson been alive, such an order would have been swiftly understood and instantly carried out. But Ewell was no Jackson—who was?—and despite repeated urging from his subordinates, Old Bald Head hesitated to order a new attack until his last division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson, had reached the field. Ewell’s senior division commander, Maj. Gen. Jubal Early, did not want to wait. Pointing to the dark form of Culp’s Hill, half a mile away, Early warned, “If you do not go up there tonight, it will cost you ten thousand men to go up there tomorrow.” Early’s figures were off, but his underlying assumption was all too correct. Hundreds of II Corps soldiers would lose their lives proving the rightness of his perceptions.

Major General Isaac Trimble, another of Ewell’s aides, was even more vociferous in calling for a renewed attack on the Union troops. “General,” demanded Trimble, “don’t you intend to pursue our sweep and push the enemy vigorously?” Pointing to Culp’s Hill, he advised: “You should send a brigade with artillery to take possession of that hill. Give me a division and I will engage to take that hill.” When Ewell declined, Trimble persisted. “Give me a brigade, and I will do it,” he said. Still no reply. “Give me a good regiment and I will take that hill.” Ewell, tiring at last of the unsought advice, spluttered, “When I need advice from a junior officer, I generally ask for it.” Trimble, disgusted, threw down his sword and stalked away.

“Old Clubby” Fails to Take Culp’s Hill

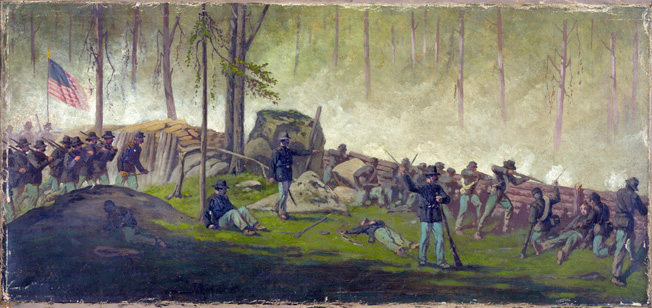

While the Confederates were arguing among themselves, the Union defenders atop Culp’s Hill were taking full advantage of the heaven-sent respite. The first Federal troops on the hill were remnants of the famed Iron Brigade, which had been badly cut up in the day’s fighting. Elements of the 7th Indiana Infantry joined the Iron Brigade on the west brow of the hill along with a lone Union battery that Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock had personally dispatched to help hold the rise. While Johnson’s men, slowed by a III Corps wagon train that blocked the road, straggled onto the field, Ewell allowed Early’s men to bivouac for the night and departed the front himself, leaving behind a rather casual order for Johnson to occupy Culp’s Hill when he arrived. Instead, Johnson postponed any further action after a scouting party ran into Union skirmishers at the base of the hill. All that night, the ringing of Federal axes indicated to the veteran Confederates below that the position was being fortified.

Johnson’s indecisive actions did not endear him to his men, who were not quite sure what to make of their new commander. Johnson was as profane as Ewell and nearly as eccentric. A serious foot wound incurred at the Battle of McDowell caused him to carry a large, stout cane—the men called him “Old Clubby” as a result. They also called him “Allegheny Ed” and “Fence Rail Johnson” in honor of his slender figure. Johnson’s booming voice, oddly shaped head, and peculiar habit of winking incessantly with one eye unnerved some of the soldiers. One young private termed him “one of the wickedest men I ever heard.” Another called him, not entirely unfondly, “a stirring old coon, always on the alert.” Perhaps, in calling off the evening assault, Johnson had been too alert.

Delaying the Attack

At daybreak on July 2, Brig. Gen. John Geary’s division from Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum’s Union XII Corps moved into place on Culp’s Hill. Veteran soldiers to a man, Geary’s experienced troops immediately began cobbling together a long line of breastworks along the crest of the hill. There were actually two peaks on the hill, located 400 yards apart. The higher peak bearing the general place name, overlooked Rock Creek, which flowed to the east; the lower peak, called Stevens Knoll, was separated from the summit by a narrow saddle notching the hill from east to west. Bordering the hill on the southeast was a marshy meadow with a stone wall running from Rock Creek to the saddle of Culp’s Hill 850 yards away. On the northwest, a cleared field lay adjacent to Spangler’s Spring, a popular picnicking spot for residents before the war.

The ever-aggressive Lee had wanted Ewell’s corps to attack at daybreak, timing the assault to coincide with that of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s I Corps attack on the Union left. The joint assault had already been pushed back. The methodical Longstreet was typically slow to move into place, and an impatient Lee went over to personally survey Ewell’s position at 9 am. From the cupola of the nearby Adams County poorhouse, Lee surveyed the Union position on Culp’s Hill. “The enemy have the advantage of us in a shorter and inside line and we are too much extended,” Lee observed. In gently veiled criticism of Ewell’s failure to attack the night before, he added, “We did not or we could not pursue our advantage of yesterday, and now the enemy are in a good position.” Reluctantly, he postponed the attack until 4 pm.

Further delays pushed back the attack another three hours. Ewell’s men, growing bored and restless, rummaged for food at nearby farms, helping themselves to a rich array of flour, bacon, butter, milk, and preserves. Some, falling back on their rural southern backgrounds, obligingly helped the frowning Gettysburg farmers milk their own cows. Others took advantage of the delay to write letters to their loved ones back home. Sergeant David Hunter of the 2nd Virginia dashed off a few lines to his mother. “We are in all probability on the eve of a terrible battle,” he wrote. “The two contending armies lie close together and at any moment may commence the work of death. We trust in the wisdom of our Gens. and the goodness of our Father in Heaven who doeth all things well. Although we may be victorious, many must fall, and I may be among that number. If it is the Lord’s will I am, I trust, prepared to go.” It was not the sort of letter a worried mother wants to receive from her soldier-son.

“All Was Confusion and Disorder”

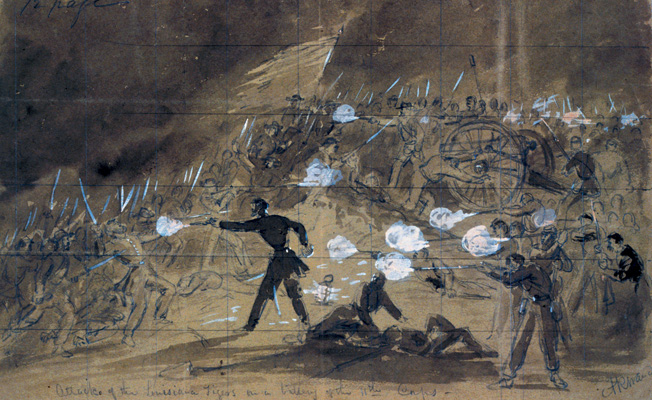

Finally, at 7 pm on July 2, Johnson gave the order to advance. Leading the attack was Brig. Gen. John M. Jones’s brigade, which advanced west from its position near Benner’s Hill. Feeling their way toward Culp’s Hill alongside a rail fence bordering the eastern edge of the woods at the base of the hill, Jones’s men waded across chest-deep Rock Creek and slogged onward in the face of largely ineffective fire from the Union artillery battery atop the hill. Following directly behind Jones’s brigade were the brigades of Brig. Gen. George H. “Maryland” Steuart and Colonel Jesse M. Williams. Like Ewell, the rather handsome Steuart, nicknamed “Maryland” to differentiate him from the more famous “Jeb” Stuart, had only recently returned to duty after spending a year recuperating from a serious wound received at the Battle of Cross Keys. Williams was commanding a brigade in the absence of Brig. Gen. Francis R.T. Nicholls, who had lost his left foot to a Union artillery shell at Chancellorsville. (The unlucky Nicholls had already lost an arm at Winchester. His luck would improve after the war, when he was elected the Democratic governor of Louisiana during the bitterly contested “stolen election” of 1876.)

In all, the three Confederate brigades totaled about 4,000 men arranged in a double line of assault. As they neared Culp’s Hill, the lines were funneled through a narrow opening between the smaller knobs to the south. In the deepening gloom, officers had to dismount and guide their men through the massive boulders in small groups. “All was confusion and disorder,” Captain Thomas R. Bucker of the 44th Virginia recalled. Red and orange muzzle flashes erupted as Union skirmishers withdrew up the hillside.

Williams’s men halted 100 yards from the enemy breastworks; no one could see where they were going. Sergeant Charles Clancy of the 1st Louisiana, carrying the regimental colors, realized to his chagrin that he had advanced too far. Before the Federal soldiers could surround him and take him prisoner, Clancy removed the flag from its staff and wrapped it tightly around his body. Somehow he managed to keep the flag concealed throughout his subsequent six-month-long imprisonment and returned it proudly to the regiment after he was exchanged that winter.

Steuart’s brigade, advancing on the left, had an easier time. The troops passed through a cornfield, waded across Rock Creek, and began climbing the eastern slope of Culp’s Hill. There was surprisingly little fire from the enemy to their front. Unknown to the Confederates, the hill had been systematically stripped of defenders as the fighting became general across the battlefield. Only a single Union brigade, under the command of 62-year-old Brig. Gen. George S. Greene, remained in place to hold the high ground at Culp’s Hill.

Had Johnson’s division made a concerted push, the Confederates might well have taken the hill. Instead, the attack continued piecemeal, degenerating into a series of isolated small-arms fights that amounted to little more than individual sniping contests between soldiers firing blindly into the darkness. The Federals, safely concealed behind their breastworks, had the upper hand, and Greene took full advantage of the edge. Despite being the oldest Union general on the field—he had graduated from West Point six years before Robert E. Lee—the white-bearded, Rhode Island-born general handled his men superbly. As a trained engineer, he had prepared a formidable defensive position, and he skillfully rotated the men in and out of the trenches to maintain an incessant fire on the attackers. By the end of the battle, it was estimated that the 1,400 men in Greene’s brigade had fired an astonishing 277,000 rounds at the Confederates, in the process destroying many of the ancient oak trees at the old picnic grounds. Greene, who bore a passing resemblance to the fanatic John Brown, was described similarly by one of his officers as “a grim old fighter.” He would not give up Culp’s Hill without a fight.

In the confusion and darkness, there were predictable incidents of friendly fire. Lieutenant Randolph McKim of the 1st Maryland, temporarily attached to Steuart as an aide-de-camp, led eight companies of the 1st North Carolina Regiment up a concealed draw in the hillside. Seeing muzzle flashes to his front, he carefully prepared an ambush, crying, “Fire on them, boys, fire on them!” Only after Major William M. Parsley of their brother regiment, the 3rd North Carolina, rushed up and shouted, “They are own men!” did McKim realize his mistake. In another incident, Major William Goldsborough of the 1st Maryland was directing part of the fighting when an officer on horseback rode up and asked casually, “How’s the fight going?” “I don’t know,” said Goldsborough noncommittally, taking hold of the horse’s bridle. “What corps is this?” the stranger wanted to know. “A Confederate corps and you are my prisoner, sir,” said Goldsborough. The rider, Union Lieutenant Harry C. Egbert, immediately dismounted and surrendered his sword.

Reinforcing Culp’s Hill

As night came on, Steuart’s men gratefully occupied some abandoned Union breastworks at the base of Culp’s Hill. There they waited out the night, snapping off occasional rounds at the enemy but taking care not to fire again on their own comrades. Goldsborough, who knew the area well, told Johnson and Steuart that his scouts had seen wagons moving onto Baltimore Pike, the main Union line of retreat, 600 yards to the west. Johnson, putting his ear to the ground Indian-style, listened to the low rumble of wheels in the distance, which he said “would indicate the enemy is retreating.” He told his staff they had carried the hill. He was wrong. What he had heard instead was two more Union brigades from Geary’s division returning to Culp’s Hill after their premature removal earlier that day. The lead regiment, the 29th Pennsylvania, marched confidently up the turnpike and reentered the woods at the base of the hill, intending to reoccupy their old position. Someone in the ranks called out a Union “Hurrah!” to announce their return. In response, a withering volley of musket fire erupted from Steuart’s men posted a mere 25 paces away.

on Cemetery Hill as darkness falls on July 2. Confederate II Corps commander Richard Ewell failed to support Hays’s assault.

The Keystone State commander, Colonel William Rickards, believing that the fire was coming from their own men, had his men hold their fire while he rode toward the low wall and called out his identity. This was met by another Confederate volley, which somehow missed hitting Rickards but convinced him without a doubt that the enemy was in force an uncomfortably short distance away. The Pennsylvanians spent the night clinging to the ground within uneasy proximity to the Rebel line.

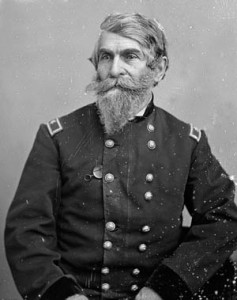

An order passed down the chain of command from General Slocum for the men to drive out the enemy at daybreak. The order, said Brig. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams, commanding Slocum’s 1st Division, was “more easily made than executed.” The 53-year-old Yale University graduate, called “Old Pap” by his soldiers, was reluctant to mount a headlong frontal attack on the Confederates now thronging the lower slope of Culp’s Hill. Instead, he told his men to hold their position until morning, “then, from those hills back of us, we will shell hell out of them.” With that, Williams casually stretched out on a flat rock beneath an apple tree for a half-hour nap. He would need all the rest he could get for the day ahead.

While Union forces continued to return piecemeal to Culp’s Hill, Confederate commanders were arguing among themselves about the failure to drive the enemy off neighboring Cemetery Hill. Recriminations flew fast and hard, but it was too late to change the day’s outcome. Lee’s headquarters sent out new orders to attack again the next morning, and Ewell, deciding that Cemetery Hill was too strongly held to take, turned his attentions back to Culp’s Hill. Johnson’s lodgment at the base of the hill was promising. Ewell dispatched reinforcements, including the vaunted Stonewall Brigade under Brig. Gen. James A. Walker. With twice as many men as he had commanded at the beginning of the attack, Johnson was ordered to attack again at dawn.

“The Whole Hillside Seemed Enveloped in a Blaze,”

As the first light of morning streaked the sky on July 3, the woods beyond Culp’s Hill erupted in cannon fire. In accordance with Williams’s plan, the 26 guns from XII Corps’ assorted batteries unleashed a skull-pounding, teeth-rattling barrage. “The whole hillside seemed enveloped in a blaze,” Goldsborough reported, “and the balls could be heard to strike the breastworks like hailstones upon the rooftops.” Withdrawing his battalion from the line of fire, Goldsborough had the men scamper for cover. All anyone could do was hunker down and wait out the Union bombardment. Then, when the fire lifted, the gray-coated brigades surged forward with a shout, bolting across terrain studded by large gray boulders that one Union officer thought resembled a herd of sleeping elephants.

Steuart’s men, leaving the relative safety of the abandoned Union breastworks, pressed forward gallantly, running into heavy fire on their right. The 2nd Virginia Regiment from the Stonewall Brigade rallied to support them, peppering the offending Union regiment, Colonel William Maulsby’s 1st Maryland, which had advanced to within 20 yards of the stone wall alongside the meadow at the base of Culp’s Hill. Maulsby’s men, from the Potomac Home Brigade, fell back to the Baltimore Pike with the loss of 80 comrades.

As Steuart’s brigade climbed the slope toward the second summit of the hill, they ran into more heavy fire. Goldsborough, at the head of his 1st Maryland Battalion, came across two 3rd North Carolina officers taking cover behind a large rock. Goldsborough asked one of the men, Major William Parsley, if he had suffered many casualties to that point. “Very much indeed,” Parsley responded. “I have but thirteen men left.” At that moment a Union bullet zipped through the air, taking down another Tarheel. “And now I have but twelve,” Parsley added laconically. Goldsborough himself was stuck in the forehead by a ball a few seconds later, but the spent round only dazed him momentarily. When he ran into General Steuart, Goldsborough warned him that the men were running dangerously low on ammunition. Steuart called for a volunteer to bring up more rounds, and Lieutenant McKim, perhaps feeling guilty for having mistakenly ordered his men to fire on their own battalion the day before, immediately offered to do so. With the help of three other men, McKim emptied two boxes of cartridges into an improvised litter made from blankets and fence rails and carried them back up the hill.

“Slapping, Stamping and Cursing”

Firing was general all along the front. On the Confederate left, Lt. Col. John Zable heard a great yell arise from his rear as the men of Colonel E.A. O’Neal’s brigade rushed to their aid. Unfortunately for them, the enormous Rebel yell attracted the unwanted attention of Union marksmen and “served no other purpose,” said Zable, “but to intensify a more galling fire in our front.” As it was, Zable’s men were safer than their would-be rescuers, since they were now so close to enemy lines that the Federals fired over their heads into the ranks of the Rebel reinforcements. For three hours the southerners withstood the murderous fire, “the most terrific and deafening that we ever experienced,” said Zable.

In the midst of the battle there were unaccountable moments of grim humor. Captain William May of the 3rd Alabama was crouching behind a rock with some comrades when one of the other men, Private Tom Powell, jumped behind another rock. Suddenly Powell leaped up again, “slapping, stamping and cursing”—he had jumped into a nest of yellow jackets. The much-afflicted private would alternately drop behind a rock to avoid enemy bullets, then leap up again when the stinging wasps became too much to bear. Somehow Powell managed to avoid being hit by bullets or dying of anaphylactic shock from the stings. For the rest of his life, May could not recall Powell’s tribulations without laughing.

Three Assaults on Culp’s Hill

Johnson’s division made three separate assaults on Culp’s Hill that morning, even though Ewell had received word 30 minutes into the first attack that Longstreet’s planned assault on the Union left had been postponed until mid-afternoon. Unaccountably, Ewell had decided to continue the attack—perhaps he did not want to seem lacking in Lee’s eyes for the second day in a row. “Too late to recall,” he responded tersely when a messenger from Lee’s headquarters urged him to call off the attack.

As the men in the 1st Maryland prepared to rush the Union position for the last time, their regimental mascot, a black Labrador retriever, broke ranks and sprinted to the front. Union Brig. Gen. Thomas Kane, commanding the 2nd Brigade of Geary’s 2nd Division, watched with horrified fascination as the dog charged straight into the blue ranks, “competing for precedence with his masters in the smoke.” The dog, said Kane, “barked in valorous glee,” but was soon limping on three legs, looking for his dead master between the two lines “or seeking an explanation of the tragedy he witnessed, intelligible to his canine apprehension.” The dog gave a last lick to a fallen soldier’s hand before being “perfectly riddled” by gunfire. Kane, who had gotten out of a Baltimore hospital bed with a bad case of pneumonia, ordered the dog buried with full military honors, since “he was the only Christian-minded being on either side.”

Despite all human and canine efforts, Steuart’s men reeled back in defeat and disarray, rallying on the far side of the Union breastworks they had occupied the night before. Steuart himself was inconsolable. Wringing his hands, he cried again and again: “My poor boys! My poor boys!” One of those boys, lying mortally wounded between the lines, struggled laboriously to load his rifle. Union soldiers held their fire, fascinated by his macabre exertions. At length the young Confederate withdrew his ramrod, cocked his rifle, placed it under his chin, and pulled the trigger. Someone joked that it had saved them a bullet.

Finally, Johnson called off the attack. “The enemy were too securely entrenched and in too great numbers to be dislodged by the force of my command,” he reported. “All had been done that it was possible to do.” Union General Alpheus Williams concurred, observing, “The wonder is that the Rebels persisted so long in an attempt that the first half hour must have told them was useless.” As Jubal Early had predicted the day before, Ewell’s delay had cost the corps severely. Forced to charge a now-strengthened position, the Confederates at Culp’s Hill had suffered some 2,100 casualties. One of those was Private John Wesley Culp of the 2nd Virginia, who died on the very hill owned by his uncle. The Union defenders lost half that number, many coming in a misguided and unnecessary attempt to retake the soon to be abandoned breastworks by the 2nd Massachusetts and 27th Indiana Regiments. Once again the ancient military maxim “Take the high ground” had been proven all too correct. Most maxims are.

General George Hume “Maryland” Steuart commanded the 2nd Maryland Regiment CSA at Gettysburg, the 1st Maryland Regiment CSA had been disbanded in August 1862.