By Joshua Shepherd

By the evening of January 22, 1944, it was increasingly apparent that a drastic shift in strategy was needed to break the bloody debacle that had developed in central Italy. Two days before, the Fifth Army’s 36th Infantry Division had launched a catastrophic assault across the Rapido River. Facing a furious gauntlet of German machine-gun, mortar, and artillery fire, the Americans had been badly mauled as they raced across the mud flats that flanked the river. By the time the attack was called off after two days of carnage, the costs were staggering. The division had sustained 2,000 casualties; on their side of the river alone, exultant German troops had recovered 430 frozen American corpses.

To Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Keyes, the veteran commander of II Corps, the primary cause of the debacle was obvious. While the Americans had attacked across the marshy bottom ground of the Rapido, the Germans retained possession of the rocky heights that surrounded the site, affording them an ideal perch from which to flail oncoming Americans with accurate fire from above. To the West Point-trained Keyes, it was a grave tactical fallacy to attack across the valley unless German positions on the high ground were reduced.

The focus increasingly shifted to a particularly conspicuous mountain that dominated the countryside for miles around: the commanding heights of Monte Cassino, which was crowned with a magnificent Benedictine monastery that possessed a fortress-like appearance. Mud-covered American soldiers cast angry glances toward the mountain and intuitively realized what the top brass had seemed to miss: enemy positions on the high ground had to be seized. Associated Press correspondent Hal Boyle was of much the same opinion. “Sooner or later somebody’s going to have to blow that place all to hell,” said Boyle, giving voice to the Allies’ frustration over the enemy’s possession of the stronghold.

The Allied campaign for Italy, as well as the legendary fight for Monte Cassino, had been borne of sharp disagreements and outright arm twisting at the highest levels. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, long the standard bearer of the fight against fascism, was determined to invade mainland Italy. It was the logical next step, he argued, to attack what he referred to as the soft underbelly of Fortress Europe.

But the American top brass was skeptical of such a move. By their reckoning, a direct invasion of France and a subsequent drive into the heart of Germany was the quickest way of winning the war. Yet it was likewise apparent that any major invasion of France was a logistical impossibility until the spring of 1944.

Such a lengthy period of idleness, Churchill asserted, would certainly nettle the Allies’ suspicious partners in the Soviet Union, whose armies were suffering astonishing casualties on the meat grinder of the Eastern Front. An invasion of mainland Italy would also tie down untold numbers of enemy troops who were desperately needed elsewhere in Nazi-occupied Europe. Furthermore, it was hoped that a robust push into Italy would topple the Fascist government of Benito Mussolini. In fact, Mussolini was voted out of power and arrested on July 25, 1943. Not surprisingly, the astute and persuasive Churchill won the argument.

By the first week of September, the Allies launched the invasion of Italy. On September 3, the British Eighth Army, led by General Bernard Montgomery, crossed the narrow Straits of Messina directly to the toe of Italy. Facing light opposition, Montgomery quickly secured his beachhead and began pressing inland. His progress, stymied by stubborn German resistance and rugged terrain, was frustratingly slow.

The direct threat to the Italian homeland, however, had the desired effect on the nation’s Fascist regime. Since Mussolini’s arrest in July, Italy’s war effort had grown increasingly feeble. On September 8, the recalcitrant Italian government publicly announced its surrender to Allied forces. Yet the announcement did little to alter the fight on the ground. Occupying German forces quickly took effective control of the nation. They seized arms, munitions, and vital infrastructure.

Despite the success of knocking Italy out of the war, the American contingent of the invasion would receive a bitter reception to the country’s mainland. Beginning on September 9, the American Fifth Army under the command of Lt. Gen. Mark Clark undertook an amphibious landing near Salerno.

Clark’s troops found it impossible to effect a breakout of the landing sites and barely held a grip on the coast following a ferocious German counterattack that swept toward Salerno during the middle of September. Determined fighting finally repelled the German attacks, and by the end of the month a renewed offensive mounted by Anglo-American troops resulted in the capture of Naples, the largest city in southern Italy.

The liberation of the rest of Italy would prove far more problematic. Although initially inclined to abandon Italy following the nation’s surrender, German leader Adolf Hitler was convinced of the need to maintain a tight grip on the peninsula in order to keep Allied troops as far from the German homeland as possible. Hitler knew it was of paramount importance to keep the Allies from establishing airfields in Italy with which to bring their overwhelming air power against Germany. Sensing the grand strategic stakes at risk in the war for Italy, German troops would fight a tenacious defensive war there.

Heading up the German war effort in Italy was a gifted and widely experienced career officer, Field Marshal Albrecht Kesselring. In the grinding defensive battle for the Italian peninsula, the field marshal would prove a resourceful and clever opponent.

Although greatly outmatched in manpower and matériel, Kesselring enjoyed a decisive advantage in terrain. Much to the chagrin of the Allies, he made the most of it.

Overall command of ground forces in Italy fell to British General Sir Harold Alexander, commander of the 15th Army Group, composed of Clark’s Fifth Army, which pushed up the western flank of the peninsula, and the British Eighth Army, by that time under the command of Lt. Gen. Sir Oliver Leese, which pressed north along Italy’s east coast. Due to the barrier of the Apennines, each army was largely on its own.

Two primary roads led north toward Clark’s ultimate objective at Rome. Near the coast, Route 7 led north to the capital. Farther inland, Route 6 twisted through far more forbidding terrain before reaching the flatlands of the Liri Valley south of Rome. After the painfully slow campaign through the rugged hills of southern Italy, the Liri Valley offered the tantalizing prospect of a swift end to the bloody war of attrition that had unfolded in Italy.

By mid-January 1944, lead elements of Clark’s army mounted the heights of Monte Trocchio but were forced to halt the advance. To the north of Monte Trocchio lay a three-mile-wide swath of open ground that gave German gunners a nearly unobstructed field of fire. The main route to Rome was also blocked by the Rapido River, an aptly named tributary of the Garigliano River whose narrow waters were nonetheless treacherously swift. Situated on the north of the Rapido was the town of Cassino, a wayside city that now found itself at the epicenter of the fight for Europe.

Beyond Cassino, forbidding terrain assured the Allies of a difficult and bloody fight. In fact, the heights beyond the Rapido, dominated by steep ridges, plunging ravines, and jagged peaks, constituted some of the most rugged terrain in central Italy. The ground was entirely impracticable for maneuvering armored columns; even for veteran infantry, the rocky inclines, paired with a stout German defense, would require a herculean effort to overcome.

Ironically, the hellish no-man’s land at Cassino was dominated by an imposing hill that had served as a bastion of religious tranquility for nearly 1,500 years. Commanding the city to the west were the soaring heights of Monte Cassino, which rose some 1,600 feet above the valley. The mountain was crowned with by the Abbey of Monte Cassino, whose gleaming travertine walls, 10-feet thick, could be seen by troops miles away.

By the winter of 1944, the abbey occupied the most strategically valuable real estate in Italy. Despite its military potential, the seven acres of the magnificent monastery were regarded as off limits for both Allied and Axis forces. Both sides adhered to a tentative policy, which was subject to military necessity, of preserving artistic and cultural sites in Italy.

To block the Allied route to Rome, Kesselring ordered the construction of a seemingly impregnable defensive position. It stretched for 100 miles from the Tyrrhenian Sea in the west to the Adriatic Sea in the east. Christened the Gustav Line, the fortified network bristled with thousands of artillery pieces, mortars, machine-gun nests, bunkers, and minefields. The fieldworks, laid out in multiple, mutually supporting lines to maintain a defense-in-depth, was an impressive display of German military engineering.

Perhaps most importantly, Kesselring had at his disposal 20 divisions that included infantry, panzer, panzergrenadier, and airborne units. Although many units had been reinforced with foreign conscripts, Kesselring’s forces possessed a hardened core of German veterans who were fiercely determined to keep the Allies out of the Fatherland.

As the Allied high command made plans to breach the Gustav Line, it hoped that the worst of the terrain could simply be bypassed. Largely due to Churchill’s prodding, the Allies planned a large-scale amphibious landing at Anzio, well behind German lines. Paired with a direct thrust into German positions by the main body of Clark’s troops, it was hoped that the Anzio landings would quickly pry German defenders loose from the Gustav Line.

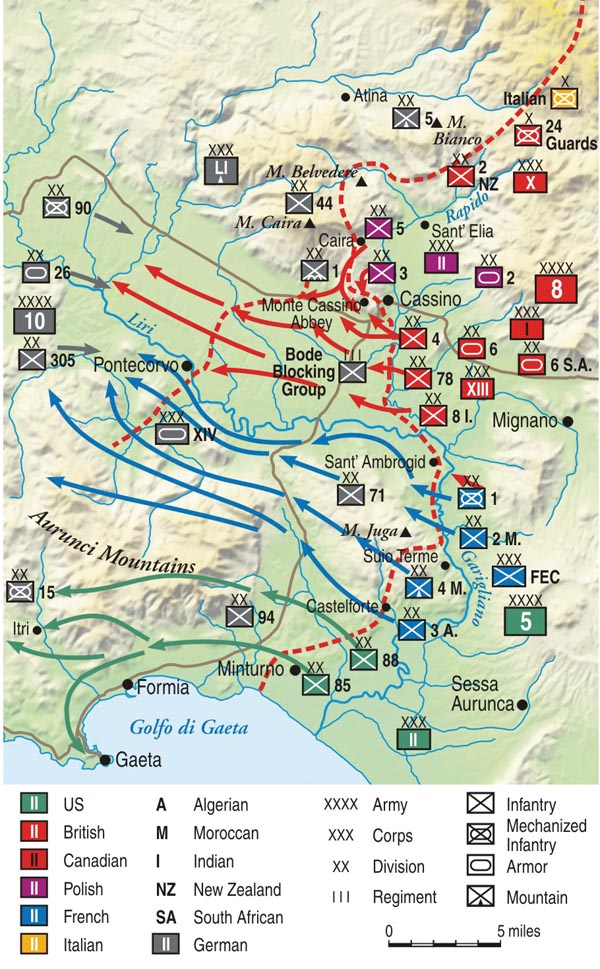

In preparation for the landings, Alexander and Clark sketched out an operation against enemy positions opposite the Fifth Army. Rather than directly assault Cassino and the formidable heights behind the town, Allied forces would execute a wide pincer move designed to envelop the position. To the north of the town, General Alphonse Juin’s French Expeditionary Corps would push into the mountains before swinging south behind the town and abbey. On the left, the British X Corps would cross the Garigliano River and seize the high ground beyond. South of Cassino, the American 36th Division would attack across the Rapido and assault the German center.

Late on the evening of January 11, 1944, Juin’s troops moved into their assault positions. The spirited Frenchman, an experienced veteran and skilled tactician, led a colorful corps of colonial troops renowned for impetuous ferocity. Drawn primarily from the French possessions of North Africa, the troops of the French Expeditionary Corps were regarded as poorly disciplined but well suited for the rigors of mountain fighting. The Goumier were the scions of a fierce martial tradition in Arabic and Berber culture, and they waged war on their own terms.

In the hope of securing the element of surprise, the artillery remained quiet, leaving the Goumier to attack enemy positions with small arms. Early on January 12, Juin’s Moroccans and Algerians were on the move, rushing headlong into the hills north of Cassino. Accustomed to rough terrain, the hard-fighting tribesmen made good progress as they stormed German positions perched in the rocky hillsides. When the Algerians seized the heights of Monna Casale, the Germans counterattacked. Bloody fighting ensued with the position changing hands four times during a horrific battle that did not end until sunset.

Despite initial success, the attack slowed as it encountered more experienced enemy troops. Generalleutnant Julius Ringel’s 5th Mountain Division, an elite unit trained specifically for the rigors of such combat, fought stubbornly in the hills. After four days of bloodletting, the French assault had come close to success but finally stalled. Juin pleaded for reinforcements, convinced that just one more division would enable him to achieve a breakthrough.

On January 17, British X Corps artillery unleashed a deafening barrage against German positions on the north bank of the Garigliano River. Lt. Gen. Sir Richard McCreery hurled his three divisions across the Garigliano following the artillery fire. Furiously paddling assault boats, the Brits smashed into the Generalleutnant Bernhard Steinmetz 94th Infantry Division, a woefully inexperienced outfit. McCreery’s troops pushed their way into the high ground beyond the river but were badly mauled in the process. Despite heavy casualties, the British drove several miles in two days of fighting.

But the German defenders were not idle. With his lines south of Cassino bent to the breaking point, German XIV Panzer Corps commander General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin was a formidable opponent. As the Allies stepped up their attacks, he scrambled to reinforce exhausted frontline units with fresh ones. By birth a Prussian nobleman, he was a field commander with a decidedly cerebral approach to the art of war. A devoutly religious man who was privately disgusted with Nazi atrocities, Senger was under no illusions about the outcome of the conflict. “The rotten thing is to keep fighting and to know all along that we have lost this war,” he observed. Nevertheless, he fought tenaciously for the German people and homeland.

Senger bolstered his front lines with some of the toughest reserves available. Inserting the 90th Grenadier Division and the 29th Panzergrenadier Division, Senger succeeded in stabilizing his position. British X Corps units were forced to fall back and consolidate their modest gains. On McCreery’s right, though, the British would make one more attempt to smash through the Gustav Line behind the Garigliano.

Hoping to follow up on the promising attack launched by its X Corps comrades, the British 46th Division attempted a crossing of the river on January 19. The crossing, however, quickly degenerated into a debacle. The swift waters of the Garagliano played havoc with the assault boats, which were unable to make headway in the current. British troops were badly shot up by machine-gun fire, which swept the surface of the river and rendered a successful crossing all but impossible. Only a handful of troops succeeded in reaching the north bank.

For the Allies, matters would only get worse. In the river bottoms just south of Cassino, one more push into German positions was planned for the troops of Maj. Gen. Fred Walker’s 36th Infantry Division. Their assigned crossing point was in full view of German observers perched on Monte Cassino, and the river below the city was extraordinarily swift.

For his part, Walker was anything but optimistic over the prospects. Stymied in his attempts to have the attack shifted to more favorable ground upriver, he grew increasingly dejected over the fate that awaited his men. “I don’t see how we, or any other division, can possibly succeed in crossing the Rapido,” he confided to his diary.

Despite such misgivings, the attack went forward on the evening of January 20. The attack targeted the village of Sant’Angelo, with Walker’s 141st Infantry Regiment going in on the right and the 143rd Infantry Regiment on the left. From the outset, the attack went awry. As the hapless American soldiers rushed forward, they were exposed to a withering fire from the crack troops of Generalleutnant Eberhard Rodt’s 15th Panzergrenadier Division. Running a gauntlet of machine-gun, mortar, and artillery fire, the men of the 36th Infantry Division suffered heavy casualties before they even reached the Rapido.

Once the troops reached the riverbank, the situation did not improve. Facing a hailstorm of German fire, dozens of men were cut down as they struggled to get their boats in the river. Most boats were shredded by enemy fire or simply floundered in the waters of the Rapido. By dawn of the next morning, only two demoralized battalions, cowering in mud on the north bank, had succeeded in getting across the river. Two more days of bloody stalemate induced Clark to authorize a withdrawal.

The repeated drubbings that Allied forces had endured in attempting to cross the Garigliano and Rapido Rivers forced Clark and his senior commanders to refocus their energies toward the heights beyond the town of Cassino, in particular the commanding eminence of Monte Cassino. It was hoped that the timeless military maxim of occupying the high ground would finally pry the Germans loose from the Gustav Line.

Clark again unleashed Juin’s French Expeditionary Corps on January 24. The fierce French colonial troops stormed into German lines north of Cassino, breaking through initial defenses and eventually seizing Monte Belvedere five miles inside the Gustav Line. Stalled by an increasingly determined German defense, Juin issued fruitless requests for reinforcement, without which, he said, his exhausted troops could do no more.

While the French were struggling through the mountains to the north, the Americans of the 34th Infantry Division attacked the Gustav Line north of Cassino. They were able to force their way across the Rapido and then seized the ruins of former Italian Army barracks on the German side of the Gustav Line. However, fierce enemy counterattacks drove back the exhausted Americans beyond the east bank. Led by the tenacious Maj. Gen. Charles Ryder, the 34th Division launched repeated assaults toward the river, only to be repulsed with heavy casualties.

Such persistence finally paid off. On January 27, Ryder had secured a lodgment on the German side of the river, and two days later pushed inland. Stubbornly fending off enemy counterattacks, Ryder’s men pushed their way through German defenses, capturing the village of Cairo on January 30.

The fight to break the German hold on the Gustav Line was far from over. Ryder, his left on the Rapido and his right in the mountains, turned his division south in a bid to capture the town of Cassino. With armor support deployed in the river bottom, his troops seized the Italian barracks and then forced their way into the outskirts of the town. A stubborn German defense turned brutal house-to-house fighting into a bloody draw, and the Americans were unable to seize the town.

In the hope of seizing Monte Cassino and unhinging the Gustav Line, Clark ordered an all-out attack February 7. While the French advanced on their right and the British X Corps launched an attack on their left, the Americans of the 34th and 36th Divisions assaulted the high ground above Cassino. The fighting turned into an infantryman’s nightmare as exhausted American soldiers groped their way through the jumble of rocky peaks north of Monte Cassino.

The Germans had fortified every high point and rushed in reinforcements from the veteran 90th Grenadier Division, as well as the fearsome paratroopers of Maj. Gen. Richard Heidrich’s 1st Parachute Division. Vicious see-saw fighting resulted in high casualties on both sides. The Americans fought their way onto Snakeshead Ridge, a dominating line of hills that led toward the monastery. Although they briefly threatened Monte Cassino itself, Clark was forced to call off his exhausted divisions and consolidate Allied gains.

Fortunately, Clark had fresh reinforcements at hand with which to press forward the attack. Beginning in late January, Alexander transferred three Commonwealth divisions from the British Eighth army: the 2nd New Zealand Division, the 4th Indian Division, and the British 78th Division. He placed the three divisions, which formed the II New Zealand Corps, directly under Clark’s control. The units were under the command of Lt. Gen. Bernard Freyburg, who had led the defense of Crete in the face of General Kurt Student’s airborne invasion in the spring of 1941.

After enduring repeated defeats in front of the Gustav Line, Allied troops were highly suspicious that German troops were using the abbey as a ready-made observation post. A number of infantrymen reported that they had seen Germans behind its walls or even in the windows. Convinced that the Germans had fortified the locale and unwilling to see his men shed blood unnecessarily, Freyburg called for the destruction of the monastery before his troops launched another attack.

Ironically, it appears that such suspicions were groundless. Although the mountain itself was occupied by German troops, the abbey grounds were populated with little more than Benedictine monks and terrified civilians. The gentleman warrior at the head of the XIV Panzer Corps, von Senger, was circumspect in his observance of the traditional rules of war as they applied to the abbey. Once invited to dine in the building, von Senger respected the privilege by refusing to even look out the windows in the direction of Allied positions.

Clark, who was highly skeptical of reports that the enemy had entered the abbey, refused to authorize an attack on the monastery. Conflicting intelligence reports did not help matters. On February 14 Maj. Gen. Ira Eaker, commander in chief of the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces, and Keyes made reconnaissance flights over Monte Cassino. While Eaker claimed to have seen Germans in the abbey compound, Keyes reported that he saw nothing. Ultimately, political considerations determined the outcome of the priceless monastery on Monte Cassino. Largely to assuage Freyburg, Alexander overruled Clark’s objections and authorized the destruction of the abbey. Clark correctly predicted the outcome. “If the Germans are not in the monastery now, they certainly will be in the rubble after the bombing ends,” he said.

On the morning of February 15, the Allied air fleet launched Operation Avenger, aimed at the complete destruction of the abbey. About 250 bombers flew repeated attacks over the mountain, dropping 600 tons of ordnance that rocked the mountain and shattered the walls of the monastery. Allied artillery also bombarded the mountaintop, lobbing shells into the ruins. Terrified civilians who had not fled the heights were caught in the maelstrom. Many of these noncombatants perished during the bombing and shelling. By the end of the day, much of the monastery had been reduced to a confusing labyrinth of boulders and dust.

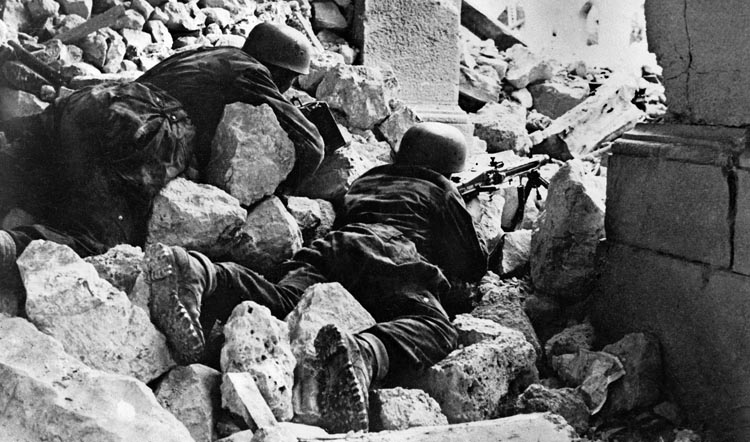

True to Clark’s fears, German troops immediately moved into the rubble. Elements of the 1st Parachute Division swiftly took up positions in the abbey grounds, which afforded a commanding position of the valley below and dominated the Allied approaches. Far from blasting a hole in the Gustav Line, the Allies had inadvertently transformed Monte Cassino into a ready-made fortress for some of the toughest troops of the German war machine.

Rather than launch an attack in the immediate aftermath of the bombing, Freyburg sat tight for the better part of the day. As darkness fell, an attack was launched, albeit by a single infantry company of the 1st Royal Sussex Regiment, which groped its way through the darkness toward Point 593 on Snakeshead Ridge. Not unexpectedly, the British troops were mauled as they assaulted formidable German positions. The New Zealand Corps kept up the pressure but accomplished little. On February 17, Freyburg sent in elements of the 4th Indian Division, who fared little better. The hard-fighting mountain troops of the 1/2nd Gurkhas battled their way toward the base of Monte Cassino but were finally driven back with heavy casualties.

That same night, the 28th Maori Battalion of the 2nd New Zealand Division attacked directly across the Rapido River with the aim of capturing the vital railway station south of Cassino. The Maoris enjoyed initial success, forcing their way through German defenses and seizing the station. But engineers, working feverishly in a storm of German artillery fire, were unable to bridge the river and bring up armor support. Driven back by a fierce German counterattack the following day, the New Zealanders were forced to the east bank of the Rapido.

The horrors of the Italian Campaign offered little respite for the embattled infantrymen who struggled for every rugged inch of ground at Cassino. Plans for yet another try at the Gustav Line unfolded immediately, to be carried out once again by the II New Zealand Corps. Freyburg pressed for yet another massive bombing run, this time targeting the town of Cassino. On the morning of March 15, Allied bombers flew over the Rapido and unleashed a torrent of explosives into the heart of the town. As many as 900 artillery pieces lent their weight to the attack. In four devastating hours the once pastoral town was reduced to rubble.

Freyburg’s troops stormed into Cassino on the heels of the bombardment, hoping to quickly overrun dazed German defenders. They were sorely disappointed. Tenacious German paratroopers who had survived the bombing had taken up excellent defensive positions in the rubble. The hard-pressed New Zealanders suffered heavy casualties as they battled their way into the town. As the infantry fanned out, they met with a measure of success on the margins of the town. To the west of town, the New Zealanders seized the summit of Castle Hill, a vital height between the town and the monastery. Other troops forced their way through to the railroad station.

The Kiwis failed to dislodge stubborn pockets of German defenders in the town center, and Allied tank crews found it impossible to operate in the demolished remains of the urban center. Hardened troops from the 3rd Parachute Regiment set up strongpoints in the ruins of the Continental Hotel and the Hotel Des Roses. Despite multiple attacks, the Germans defied repeated efforts to dislodge them.

In the hills west of town, the troops of the 4th Indian Division once again attempted to force their way toward the monastery. The Indians took over the fight from Castle Hill but were stopped cold in a futile push west. The men of the 9th Gurkha Rifles, braving a gauntlet of enemy fire, succeeded in seizing Hangman’s Hill, a commanding position just 300 yards from the monastery. Unfortunately, reinforcements were not forthcoming. The hardy Gurkhas fought on, cut off and isolated on the summit of the hill.

Despite the overwhelming weight of Allied forces, Heidrich’s paratroopers were far from beaten. On March 19, they struck back. German troops attacked through Cassino, aiming to dislodge the New Zealanders, but were handily repulsed. On Castle Hill, a life-or-death struggle ensued in the darkness. Elements of the 4th Parachute Regiment overran Allied outposts and then assaulted the castle directly. In a sharp and narrowly won fight, the defenders succeeded in driving off the Germans.

Freyburg had reached his limit by March 23. He recalled his battered troops and regrouped. The repeated Allied attacks on Cassino and heights above the town, largely carried out in piecemeal fashion, had been miserable and costly failures. An exasperated Churchill badgered Alexander for an explanation. “I wish you would explain to me why this passage by Cassino [and] Monastery Hill is the only place which you must keep butting at,” he said. “About five or six divisions have been worn out going into those jaws.”

It was a painful question that increasingly nagged at every Allied soldier in Italy. Determined to finally crack the Gustav Line, Alexander began transferring the bulk of the Eighth Army from the Adriatic to the Cassino sector. In six weeks, Clark was reinforced with a hodge-podge of fresh Allied divisions. Eventually, the front lines between Cassino and the sea were manned by 20 divisions drawn from nearly every Allied nation across the globe.

Alexander’s plan for a massive breakthrough, Operation Diadem, would bring overwhelming force to bear on the increasingly thin German defenses. Clark’s Fifth Army, which had taken considerable casualties in the fighting around Cassino, shifted to the left and would launch its assault along the coastal route of Highway 7. On Clark’s right, the French Expeditionary Corps would push straight into the Arunci Mountains.

To the right of the French, the British Eighth Army took up positions in the Cassino sector. The divisions poised to push into the embattled zone included troops from the far reaches of the Commonwealth: Brits, South Africans, Indians, Gurkhas, and Canadians. On the far right, the Polish II Corps, under the command of Lt. Gen. Wladyslaw Anders, prepared to attack toward Monte Cassino.

On the evening of May 11, the Allies unleashed a massive artillery bombardment designed to pulverize the Germans. More than 1,000 artillery pieces opened a devastating barrage that slammed into enemy positions along a 25-mile front. The crescendo was deafening for attacker and defender alike and shook the earth across the Rapido Valley. Allied troops were hopeful that the overwhelming firepower would reduce German positions before the infantry even came to grips with the enemy.

On the left, Clark thrust his men forward along Route 7 but faced a tough fight. On his right, Juin’s troops stormed forward, breaking the initial defenses of the German 71st Division and battering their way deep into the Arunci Mountains. South of Casino, the 8th Indian Division and the 4th British Division crossed the Rapido under heavy enemy fire. Although taking heavy casualties, the two divisions succeeded in gaining the northern bank of the river.

On the right, the final battle for the prize of Monte Cassino fell to Anders’ Polish Corps. These men had escaped Poland as it fell to the Germans and Russians in 1939. Anders exhorted his men to triumph over the Germans they deeply despised. “Soldiers! The moment for battle has arrived,” he said. “We have long awaited the moment for revenge and retribution over our hereditary enemy.” Working their way into the rugged hills north of Cassino, the Poles launched assaults along parallel rises that pointed toward the monastery. The 5th Kresowa Division attacked along Phantom Ridge, driving off the German defenders, but were battered by enemy artillery.

Along the much-contested Snakeshead Ridge, the men of the 3rd Carpathian Division ran into stiff resistance as they pushed for Point 593, a nondescript but dominant rise of rubble and boulders that controlled access to Monte Cassino. In a chaotic night fight, the Poles lashed themselves against German defenses but paid a fearful price. Hundreds were cut down by well-sighted German machine-gun fire, and the terrain made evacuation of the wounded difficult. At dawn the Poles suffered a murderous fire from German small arms, mortars, and artillery. The attack on Point 593 stalled in a bloody stalemate. Later that afternoon, a devastated Anders ordered the withdrawal of his battered troops.

After consulting with Anders, it was apparent to Alexander that the Poles would be unable to seize Monte Cassino without further support. While Anders regrouped his battered corps, plans were laid to launch a two-pronged assault to reduce enemy positions on the mountain.

By May 17, The British 4th Division attacked the southern reaches of Cassino, again bringing pressure on diehard pockets of German paratroopers still holding the town. Meanwhile, the British 78th Division, pushing north from the village of Sant’Angelo, seized Route 6 south of Monte Cassino. With the German line of retreat in threat of being cut off entirely, Anders and his Poles launched another attack from the north.

The 5th Kresowa Division attacked down Phantom Ridge, succeeding in driving off German defenders and seizing Point 601, which dominated the ridge. With Phantom Ridge secured, the lead elements of the division pressed on toward Point 593 on Snakeshead Ridge, which was under assault by the 3rd Carpathian Division. The Poles, whose homeland had been overrun and occupied by the Wehrmacht five years earlier, fought with a tenacity borne of patriotic determination and a thirst for outright vengeance. Fighting fiercely with small arms and hand grenades, the Poles rooted out the final German defenders and overran Point 593.

Ironically, the final fight for the great prize of the monastery that crowned Monte Cassino would prove nearly bloodless. With British troops positioned to race up Route 6 far in their rear, and Polish troops poised for a renewed assault, the German paratroopers who had fought and bled for so long to control Monte Cassino received orders to withdraw.

By mid-morning on May 18, cautious Polish troops inched their way toward the summit only to discover the enemy was gone. The honor of claiming Monte Cassino fell to a patrol of the 12th Podolski Lancers, who mounted the shattered walls of the monastery and raised a Polish flag. Alexander, ecstatic with the symbolic victory that had taken so long to secure, fired off a dispatch to Churchill. “Capture of Cassino means a great deal to me and my armies,” he wrote.

Indeed it did. With the walls of the monastery securely in Polish hands and German troops on the run, Allied divisions swarmed north and west. Kesselring attempted to rally his outnumbered divisions at yet another imposing belt of fortifications called the Senger Line, but was unable to stop the momentum of the Allied steamroller. On May 23, American troops began battering their way out of the Anzio beachhead, and the Allied weight in men and matériel finally began to tell. On June 4, exultant Allied troops entered Rome.

Although the costly war in Italy would linger on for another year, the bloody battles for Monte Cassino arguably constituted the most horrific struggle for the peninsula. Total German casualties exceeded 20,000 lives. The Allies paid an even greater price for the citadel; it is estimated that they suffered approximately 50,000 casualties in the bitter struggle to break the Gustav Line.

Churchill, who had lobbied vigorously for the invasion of Italy, regarded the entire operation a strategic victory. “The principal task of our armies had been to draw off and contain the greatest possible number of Germans,” he said. “This task had been admirably fulfilled.”

Such sentiments of grand strategic success were cold comfort for the common foot soldiers who had fought and bled in the horrific fight for Monte Cassino. For his part, Clark was tormented by the legacy of the clash, and his stark assessment of the brutal struggle for the limestone hills of central Italy likely came closest to the truth. “The battle for Cassino,” Clark recalled, “was the most grueling, the most harrowing, and in one respect the most tragic, of any phase of the war in Italy.”