By Michael D. Hull

They had no armor, no air support, and little hope, but the American and Filipino troops on Luzon and the Bataan peninsula waged a fighting retreat that was the longest and most gallant in U.S. military history.

Half-starved, weary, and wracked with disease, the defenders of the Philippine Islands battled superior Japanese forces for five desperate months in late 1941 and early 1942 with mostly rifles, machine guns, and hand grenades. They fought, fell back, dug in, and fought again. Promised supplies and reinforcements never arrived, and their cause was doomed from the start.

Major General Jonathan M. Wainwright, the scrawny 1906 West Point graduate and cavalryman who commanded the North Luzon Force, reported, “Our perpetual hunger, the steaming heat by day and night, the terrible malaria, and the moans of the wounded were terribly hard on the men.”

As senior field commander of the American and Filipino forces, “Skinny” Wainwright, a staff officer in World War I, had the tactical responsibility for resisting the Japanese invasion that began in late December 1941.

His soldiers kept hoping for relief, but none was coming. There would be no reinforcements for the Bataan force because of an enemy sea blockade, and because none were available, anyway, thanks to War Department lethargy. The defenders soon came to realize that they had been virtually forgotten. In distant Washington, the Philippines, a sprawling archipelago comprising 7,100 islands, “had been virtually written off as indefensible in a war with Japan.”

Despite intelligence warnings, years of preparation, and plenty of manpower, the Philippines were unready for the Japanese onslaught. General Douglas A. MacArthur, the handsome, autocratic commander of the U.S. Army forces in the Far East, had been complacent about the enemy threat and placed too much faith in the Filipino reservists he had trained for six years. Reports critical of their caliber and training never reached his desk.

MacArthur, a World War I infantry hero and dedicated career soldier, was a sympathetic and staunch ally of the Filipino people and their government, which had bestowed on him the title of field marshal in 1936. But, like many Westerners of his time, MacArthur woefully underestimated the Japanese. He believed that the United States should and could defend the entire Philippine archipelago, and his persuasive enthusiasm infected the U.S. War Department and General George C. Marshall, Army chief of staff.

MacArthur had drawn up plans for the defense of the Philippines, which were still chiefly on paper when crisis came. But, with sweeping overstatements, he nevertheless predicted a strong defense that could repel any enemy. He was enthusiastic about the military potential of the Filipinos, though, in the summer of 1941, a few months before the expansionist Japanese sprang their rampage in the Pacific, the Philippine Army was little more than a dream. Barracks, camp sites, equipment, and, above all, a cadre of trained officers, were lacking.

“When war came, not a single division had been completely mobilized, and not one of the units was at full strength,” reported an observer. “Discipline left much to be desired. There was a serious shortage in almost all types of equipment. The enlisted men seemed to be proficient in only two things: one, when an officer appeared, to yell ‘attention’ in a loud voice, jump up, and salute; the other, to demand three meals per day.”

Convinced that he was a man of destiny, MacArthur used his charm, commanding personality, and seniority to mesmerize Army subordinates in both Manila and Washington, as well as the dour General Marshall and Major General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, the good-natured chief of the Army Air Forces. Showing a political naivete characteristic of most American military leaders at the time, Marshall told a secret press briefing on November 15, 1941, that war with Japan was imminent but that the U.S. position in the Philippines was highly favorable. American strength there, he said, was far larger than the Japanese imagined.

Not only was America preparing to defend the Philippines, announced Marshall, but an aerial offensive from the islands would be conducted against Japan. Thirty-five new Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bombers were based in the Philippines, and more planes, tanks, and guns were being shipped there, he said. The islands were being reinforced daily. By around mid-December, Marshall predicted, the War Department would feel secure in the Philippines.

Enthused with the doctrines of Giulio Douhet, General William “Billy” Mitchell, Air Marshal Sir Hugh Trenchard, and Alexander de Seversky, Marshall and Arnold were pinning their hopes on victory through air power. If a Pacific war started, Marshall told the seven Washington reporters on November 15, the high-flying bombers could spearhead a successful offensive virtually single-handed. There would not be much need for the Navy, and the U.S. Pacific Fleet would stay out of range of Japanese air power in Hawaii.

The misplaced enthusiasm in Washington and Manila grew from ignorance—a failure to grasp the meaning of air power, a lack of understanding of maritime power, and a fatal myopia about the Japanese. The optimistic plans and pronouncements were to be of no avail. It was already too little and too late.

When Japanese carrier planes mauled the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor early on the morning of December 7, 1941, stunning and unifying America, the state of defense in the Philippines was pitiful. In the islands there were only two operational radar sets, the 35 B-17s, and 107 first-line Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk and Kittyhawk fighter planes of Major General Lewis H. Brereton’s U.S. Far East Air Force.

MacArthur’s ground forces there comprised about 130,000—22,400 U.S. Army regulars, including 12,000 well-trained Philippine Scouts; 3,000 Philippine Constabulary; and the Philippine Army, 107,000 strong. The 10 reserve divisions of the Philippine Army had been only partially mobilized. More than 100,000 Filipinos were in some kind of uniform, but most of them knew or cared little about the facts of warfare. The major portion of MacArthur’s army was based on Luzon, the largest of the islands, and other Filipino elements were stationed on the islands of Cebu, the Visayas, and Mindanao.

The Japanese naval and air onslaught in the Western Pacific early on December 7 was simultaneous and widespread, with strikes at British Malaya, Thailand, Singapore, Guam, Hong Kong, Wake Island, Midway atoll, and the Philippines. Malaya, Indonesia, and the British bastion at Singapore were the top enemy objectives, and the Philippine archipelago was a secondary goal. Earmarked for the Philippine invasion was the 14th Army, led by tall, clean-cut Lt. Gen. Masaharu Homma. His force comprised the 16th and 48th Divisions and the 65th Brigade, supported by the 5th Air Group, the 11th Navy Air Fleet, and the Third Fleet.

Homma, an intelligent, artistic infantry officer who had served as an observer with the British Expeditionary Force in France in World War I, was given about 50 days to complete his mission, and “little difficulty was expected” by the Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo. The plan was to advance through the Philippines from several points, converge on Manila, and grasp it in a giant vise.

The enemy blitzkrieg against the Philippines commenced 10 hours after the Pearl Harbor attack. A force of 192 Formosa-based naval bombers raided Clark Field, the key U.S. Army Air Forces base 50 miles north of Manila, and other airfields. Almost all of the American planes at Clark Field—parked wingtip to wingtip, with no fighter cover, while their crews were having lunch—were demolished. That night, irascible little Admiral Thomas C. Hart withdrew most of his tiny U.S. Asiatic Fleet—three cruisers, nine destroyers, and other craft—from its Cavite base in Manila Bay and headed southward to Java, out of the range of Japanese bombers.

The withdrawal, ordered by the Navy Department, left only four destroyers, 28 submarines, a squadron of flying boats, and a patrol torpedo-boat flotilla, together with a U.S. Marine regiment, in the Philippines. MacArthur’s army was now without naval support. Cavite, meanwhile, was wrecked by enemy planes on December 10.

The invasion of the Philippines began early that same day with probing attacks. Four thousand troops landed at Aparri and Vigan, on the northern end of Luzon, and another force went ashore on December 14 at Legaspi, on the southern end.

The main Japanese assault came at 2 a.m. on December 22, when 43,000 men of General Homma’s 14th Army started landing at the southern end of Lingayen Gulf on the western coast of Luzon, 125 miles north of the Philippine capital. The landings were slowed by rough seas, but there was virtually no resistance on the beach. Under complete air superiority, Homma’s force expanded its beachhead, swiftly linked up with the Aparri-Vigan invaders from the north and pushed southward toward the plains leading to Manila.

The invaders faced weak and uncoordinated opposition, and most of the subsequent Japanese landings were virtually uncontested. Many of the Japanese landing beaches had been anticipated, but the Allied force was inadequate for the defense of the lengthy Luzon coastline. The strategic position was hopeless for MacArthur’s army.

After the first shots had been fired, Filipino soldiers broke and fled, with many of the divisions from which MacArthur had hoped so much melting away into the hills. Some of the Filipinos became guerrillas, and most returned to their homes.

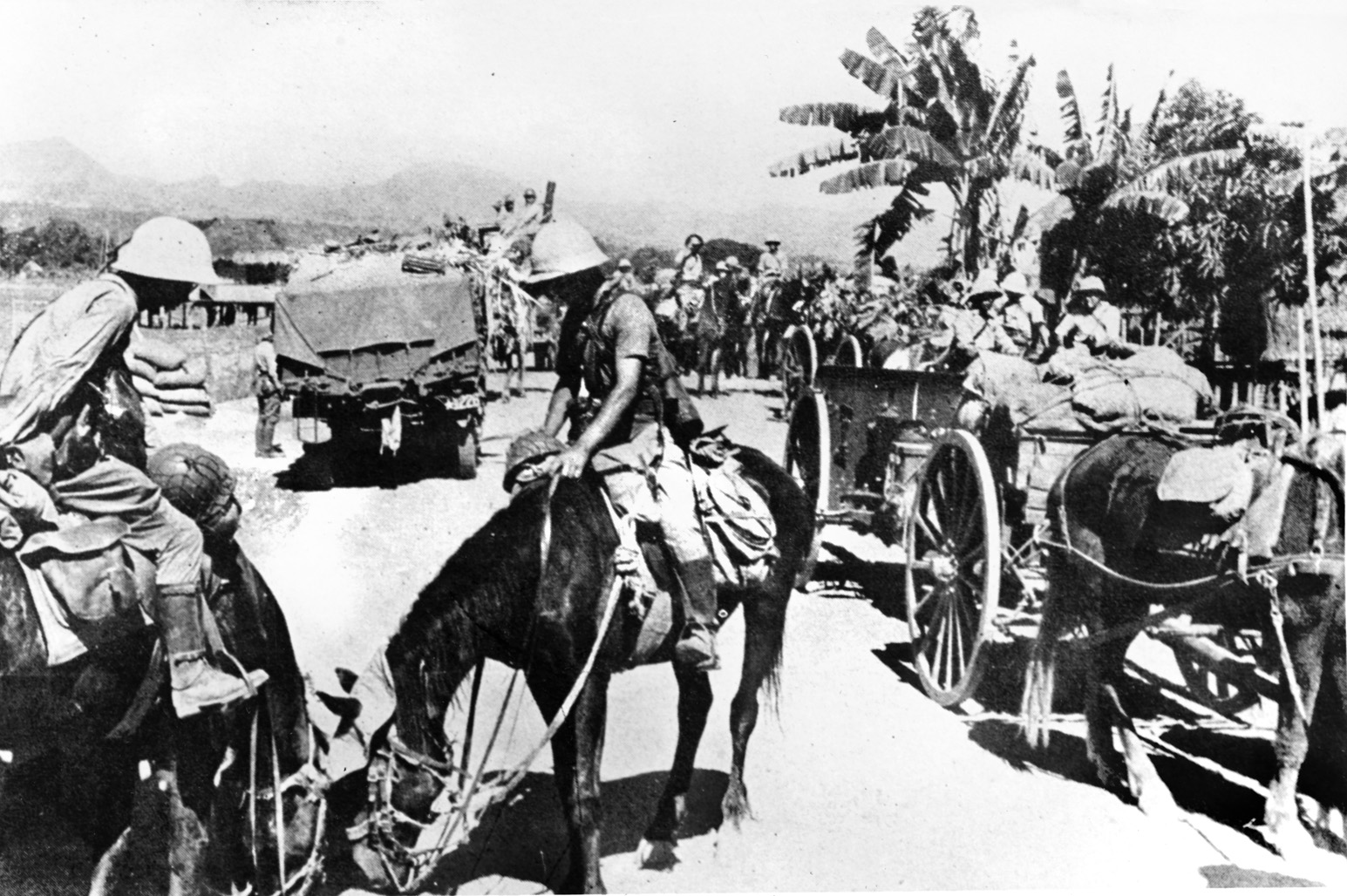

The Japanese landed tanks and artillery pieces and rolled steadily southward along Route 3, the paved highway leading to Manila. Only the steadiness of a few U.S. Army units and the valiant Philippine Scouts prevented an early disaster. Fearing a rout, General Wainwright rushed northward his handful of Philippine Scouts and 850 men of the 26th Cavalry Regiment. It was the U.S. Army’s last regiment to ride into action on horseback. The action cost the regiment 675 men. Wainwright asked permission to pull back. His men withdrew southward, turning again and again to fight desperately and try to slow the enemy advance.

With no naval or air support, the situation was worse than MacArthur had feared. Five thousand Japanese assault troops went ashore on the large island of Mindanao, at the southern end of the archipelago, on December 20, and other units overran the strategic port of Davao later that day. Leapfrogging farther south to Jolo Island and northern Borneo, the enemy severed the route between the Philippines and the rapidly expanding Allied base in Australia.

During the night of December 23, a fleet of 24 Japanese troop transports landed 9,500 troops at Lamon Bay, 60 miles east of Manila, and the Japanese 16th Division was advancing on the capital in three columns. MacArthur realized on the morning of December 24 that his forces were caught in a giant pincers movement and ordered the two divisions of his South Luzon Force to retreat into the Bataan Peninsula, a 530-square-mile finger of land on the west coast between Manila and the South China Sea. The American Far East commander was now convinced of the poor fighting qualities of the Philippine Army. The Japanese expected a quick victory, and one of Homma’s generals compared the Allied withdrawal to a cat entering a sack.

The battle in the south was over before it started, and General MacArthur was forced to order his headquarters transferred to the tadpole-shaped Corregidor Island three miles south of Bataan. Known as the Gibraltar of the East, “The Rock” was heavily fortified with 56 big Coastal Artillery guns and mortars of World War I design, 24 three-inch antiaircraft batteries, and 48 machine guns. The rocky, four-mile-long island featured docks, an airstrip, and an intricate, bombproof tunnel system housing headquarters, barracks, workshops, storehouses, and a hospital. Just south of Corregidor were three tiny satellite islands—Caballo, Carabao, and El Fraile—each fortified with coastal batteries, mortars, and antiaircraft guns.

A gloomy Christmas Day dawned for MacArthur and his men. That morning, the general reviewed the grim situation and radioed for reinforcements, but there were none. He announced that he was abandoning Manila, declaring it an open city to prevent further destruction. The capital had been heavily bombed for two days.

Japanese troops captured Clark Field on December 29 and marched into Manila on January 2, 1942. Expecting a prompt Allied surrender, the enemy high command withdrew some Philippine units to the Dutch East Indies. Meanwhile, American traffic—trucks, 155mm field guns, naval guns, buses, cars, taxicabs, and oxcarts—moved toward Bataan from every direction. The peninsula was soon bedlam as thousands of terrified Filipino refugees streamed in ahead of Homma’s army. MacArthur believed that Bataan—with its jungles, ravines, tangled undergrowth, bamboo groves, two extinct volcanoes, and swampy rice paddies—would be easy to defend, and that outflanking by the Japanese was impossible. Unfortunately, so was retreat.

By early January, the U.S. and Filipino troops were dug in astride the mountainous jungle at the base of the peninsula. The left flank was held by the First Corps led by General Wainwright, and the right by the Second Corps under Major General George M. Parker, Jr., an Iowa-born veteran of the 1916-17 Mexican border campaign. In the middle, the almost impassable, 4,111-foot Mount Najib in the Zambales Range was defended only by patrols.

Although dumps had been set up on the southern tip of Bataan and Corregidor’s ration reserves had been calculated for a six-month stand, the supply situation was deplorable from the start. About 80,000 troops and 26,000 Filipino refugees were on the peninsula, with six months’ provisions for only 40,000 mouths. Food and fuel were soon in short supply. The U.S. command went on half-rations at once. Yet, morale was high; the men were tired of retreat and wanted to stand and fight.

Japanese units followed the Allied defenders into the peninsula on January 2. U.S. forces held the high ground, and American and Filipino artillery dealt severe damage to the enemy. But the Japanese kept coming. Wainwright’s men repelled assaults at several locations, most notably on the jungled slopes and sugar cane fields around Mount natis. Japanese attacks on both Allied flanks were repulsed, but infiltrating elements crossed Mount Natib and threatened to split the American position.

On the afternoon of January 10, Japanese columns were only 20 miles from Mariveles, the main U.S. base at the southern tip of Bataan, when they were suddenly subjected to a murderous eruption of shellfire. Entire enemy platoons were blown to bits. They had blundered into the Abaya Line, where three divisions of General Parker’s Second Corps were waiting with 200 field guns. But the Japanese advance continued.

On January 22, enemy troops burst out behind the Abucay Line. Taken by surprise, Filipino battalions panicked and ran southward, forcing Wainwright and Parker to order a general retreat. Their men pulled back, stood, and fought gallantly, blew up bridges and demolished river crossings to delay the enemy, and pulled back again. The situation worsened before the relentless Japanese onslaught, and Allied hopes waned. Ammunition and food supplies ran lower, and before long the soldiers were forced to eat horses, mules, and monkeys. There was no fodder for the remaining cavalry horses and mules, and a tearful General Wainwright had to order his prize jumper named Joseph Conrad to be destroyed.

Twenty thousand men were felled by malaria, and thousands more were stricken with dysentery, scurvy, hookworm, and beriberi. Wainwright reported to MacArthur that men were so sick and hungry that they could barely crawl out of their foxholes and that barely a quarter of his army was still fit to fight.

Gaunt, weary, and puffing on Lucky Strike cigarettes, MacArthur directed the Bataan campaign from his command post in the 1,400-foot-long, dank Malinta Tunnel on Corregidor, now being pounded by Japanese bombers. He agonized about the trapped, desperate Bataan defenders, yet he had paid only one day’s staff-car visit to the peninsula early in the campaign. No one around the legendary general questioned his bravery, but soldiers on Bataan began to call him “Dugout Doug,”

On January 13, ailing Philippine President Manuel Quezon had sent a radiogram to President Franklin D. Roosevelt through MacArthur, complaining that FDR had broken his pledge to send aid. Quezon appealed for immediate American force against the Japanese invaders. MacArthur hoped that Quezon’s plea would stir up General Marshall and the War Department. But Roosevelt and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson privately informed British Prime Minister Winston Churchill that they considered MacArthur’s army doomed, and Stimson wrote in his diary, “There are times when men have to die.”

MacArthur, meanwhile, sent an incongruous message to his men on Bataan. “Help is on the way from the United States,” he promised. “Thousands of troops and hundreds of planes are being dispatched. No further retreat is possible. We have more troops in Bataan than the Japanese have thrown against us; our supplies are ample; a determined defense will defeat the enemy’s attack …. I call upon every soldier in Bataan to fight in his assigned position, resisting every attack. This is the only road to salvation. If we fight, we will win; if we retreat, we will be destroyed.”

Few Americans on Bataan believed it, but MacArthur’s words inspired the Filipinos. The 51st Philippine Infantry Division launched a determined counterattack and carved out a salient. But a Japanese regiment burst out of the jungle, outflanked the Filipinos, and put them to flight.

Between January 26 and February 13, Japanese troops made amphibious landings on the western coast of Bataan, well behind the battle line, but they were repulsed by desperate counterattacks, heroic harassment raids on enemy shipping by a handful of U.S. Navy patrol torpedo boats, and artillery fire from Corregidor’s big guns.

On February 8, a distraught General Homma halted attacks on the main front and waited for reinforcements from Japan. Two appeals had been rejected. Since January 9, Homma’s exhausted army had suffered considerable losses—7,000 men killed and wounded, and 10,000 sick with malaria, dysentery, and beriberi.

MacArthur continued to send heartening if unrealistic messages to his men, particularly the Filipinos, on Bataan. “I have not the slightest intention in the world of surrendering or capitulating the Filipino element of my command,” he vowed. “There has never been the slightest wavering among the troops.” While this was an exaggeration, it was truer than it had been a few weeks earlier. Wracked by malaria and dysentery, and with their uniforms in tatters, the half-starved Bataan defenders were still full of fight. The enemy had been held, for the time being, and Filipino recruits who had run in panic from Lingayen Gulf had become tough and dependable.

Bataan was holding on, and MacArthur and his troops became heroes on American front pages and radio broadcasts. Aides on Corregidor issued glowing dispatches about “MacArthur’s heroic resistance,” some newspapers dubbed him the “Lion of Luzon,” and President Roosevelt recommended the Medal of Honor for the general.

But time was nevertheless running out on the peninsula. Wainwright’s men became exhausted and thoroughly dispirited, food had become an obsession, and the frontline troops received only a third of a ration daily. Efforts to bring supplies to both Bataan and Corregidor through the Japanese sea blockade had failed, and by mid-February the sickness rate on the malaria-infested peninsula soared. The supply of quinine was almost gone.

Despite the florid rhetoric issued from Corregidor and the courage of the Bataan defenders, the situation was clearly hopeless, and General Marshall urged MacArthur to leave the Philippines. Although the liberal President Roosevelt abhorred his imperious personality and right-wing political bent, he was counting on MacArthur to lead a planned counteroffensive in the Pacific area. The general stalled and wired back that he and his family would share the fate of his men. But FDR persisted, and MacArthur received direct orders on February 22 to escape to Australia. Deeply troubled that his men would think he was deserting them, he considered disobeying the orders, but his aides persuaded him that he could do more for the Allied cause in Australia.

On March 10, 1942, General Wainwright was summoned to Corregidor, where Major General Richard K. Sutherland, chief of staff, informed him that MacArthur was leaving the next evening by PT-boat for Mindanao. From there, a B-17 would fly him to Australia.

MacArthur told Wainwright, “I want you to make it known throughout all elements of your command that I’m leaving over my repeated protests.” Shaking hands with Wainwright and giving him a box of cigars and two large jars of shaving cream, MacArthur said, “Goodbye, Jonathan. If you’re still on Bataan when I get back, I’ll make you a lieutenant general.”

At about 8 p.m. on March 11, MacArthur raised his trademark field marshal’s cap in farewell to a small group of American officers and Filipinos on a Corregidor pier as four battered boats of bearded Lieutenant John D. Bulkeley’s Motor Torpedo-Boat Squadron 3 pulled away. Their passengers were General MacArthur; his devoted, petite wife, Jean Marie; his four-year-old son, Arthur; Sutherland, and a group of staff members. Skirting Japanese minefields and naval patrols for 35 tense hours, Bulkeley skillfully navigated PT-41 and the other three craft to a landfall on the northern Mindanao coast just after dawn on March 13.

A worn-out B-17 was waiting on an airstrip, but the infuriated MacArthur refused to leave Mindanao until three new Flying Fortresses touched down on the evening of March 16. Next morning, he and his party landed at Batchelor Field, near the northern port of Darwin, and then flew on to the dusty little town of Alice Springs in central Australia. Reporters besieged the general for a statement, and he jotted a few lines on the back of a used envelope: “The President of the United States ordered me to break through the Japanese lines and proceed from Corregidor to Australia for the purpose, as I understand it, of organizing the American offensive against Japan, a primary objective of which is the relief of the Philippines. I came through and I shall return.”

MacArthur was awarded the Medal of Honor on March 28 for his Philippine leadership, set up headquarters in Brisbane the following month, and was appointed supreme commander of Allied forces in the Southwest Pacific area. With one Australian and two U.S. divisions under his command, he began planning a counteroffensive against the Japanese in New Guinea.

Back in the beleaguered Philippines, meanwhile, where the War Department had put General Wainwright in command of all forces, MacArthur’s departure brought a mixed reaction. The Filipinos regarded him as the greatest man alive, and Brig. Gen. Carlos Romulo, a former publisher who became a loyal aide, said, “America has let us down and won’t be trusted, but the people still have confidence in MacArthur. If he says he is coming back, it will be believed.”

The “Battling Bastards of Bataan” felt he had abandoned them and were less charitable. After hearing broadcasts of MacArthur’s pledge to return, many soldiers joked, “I am going to the latrine, but I shall return.”

The defenders of the peninsula fought on with morale intact, and somehow repulsed all enemy attacks. Wainwright’s post as commander of the Luzon Force had been taken over by Atlanta-born Major General Edward P. King, Jr., a quiet-spoken, courteous artilleryman who had served in the Philippines in 1915-17. Hunger and disease had worn down the 78,000 American and Filipino soldiers under his command. Of them, only 27,000 were classified as “combat effective,” and of these, three-fourths were weak from malaria. Rations were cut to one quarter, seriously impairing their stamina, and further resistance seemed suicidal.

General Wainwright rushed a cable to Washington saying that his men would be “starved into submission” unless food was sent by April 15. But there was no response. Lester I. Tenney, a young soldier from Chicago who had been stationed at Clark Field before it was seized, reported, “Our stamina was gone, our food was gone, our health was deteriorating, and our ammunition and gas had just about run out. We were helpless. We troops felt let down, even betrayed. If we had been supplied with enough ammunition and guns, troops, and equipment, and food and medical supplies, we believed that we would have been able to repel the Japanese.”

The end was near for the gallant, abandoned Bataan garrison. General Homma’s reinforcements finally arrived from Japan, and by nightfall on April 2, 1942, the eve of Good Friday, 50,000 troops were massed for an all-out attack. They were backed by 150 artillery pieces, mortars, and bombers of the Japanese 22nd Air Brigade. At 10 a.m. on April 3, Homma launched his offensive against the Bataan line, preceded by a devastating bombardment that reminded American veterans of the heaviest Western Front barrages in World War I.

The issue was no longer in doubt. American and Filipino soldiers scrambled from their foxholes, defense lines crumbled, and Japanese troops with fixed bayonets broke through the front on the night of April 6. The enemy burst through the left flank of Parker’s U.S. Second Corps and pushed it back 10 miles in 48 hours. On the left, Wainwright’s First Corps was bent back toward the sea. It bravely attempted counterattacks, but they were easily repulsed. The Second Corps, meanwhile, disintegrated.

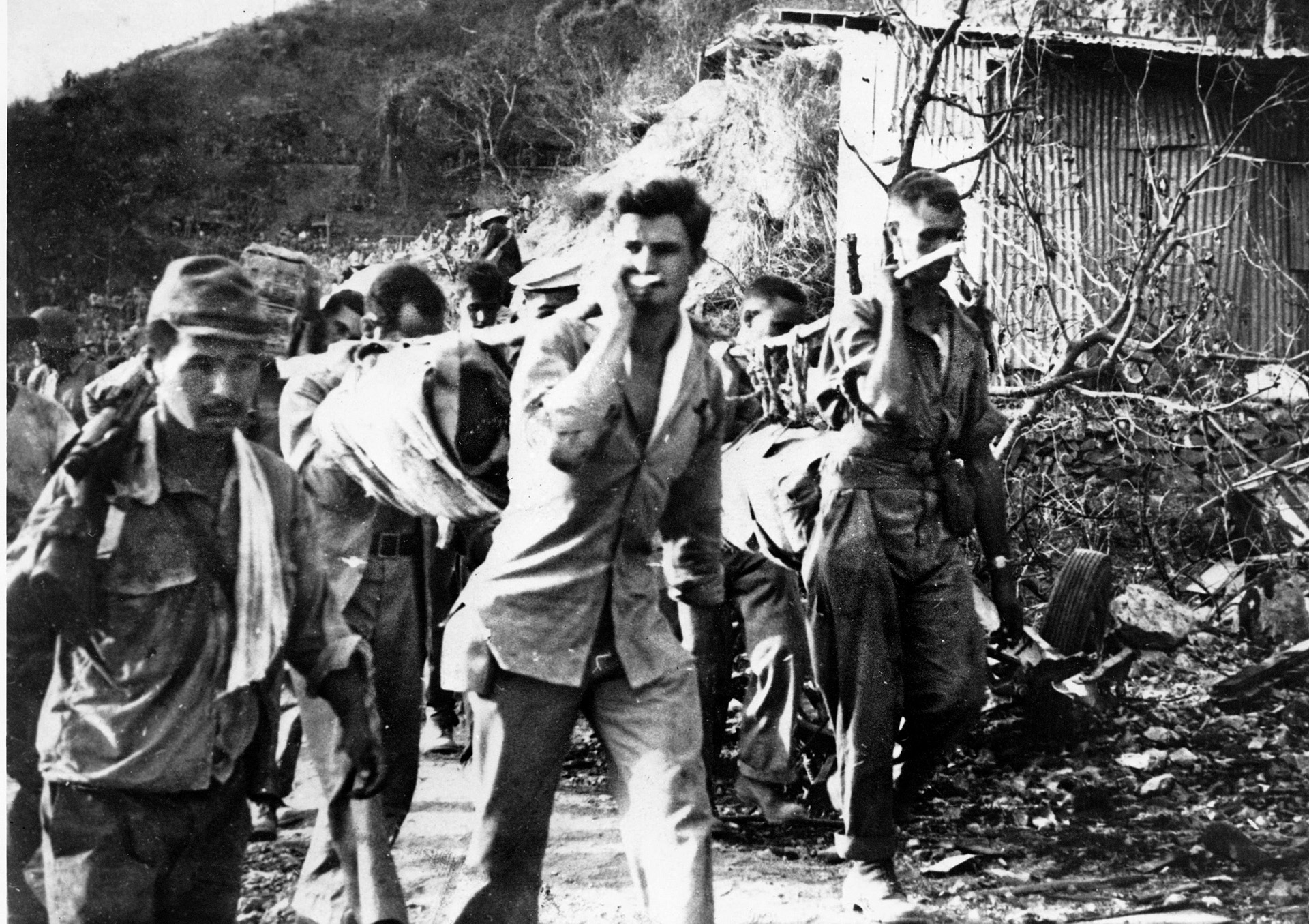

The end, when it came, was swift. Though MacArthur had ordered him not to surrender, Wainwright could not authorize his field commander, General King, to comply. King faced a bitter decision. His men were sick, starving, and lacking enough ammunition, food, and medical supplies. They had given their all with a minimum of equipment and no support, and further resistance against the ruthless Japanese was suicidal. So, King ignored MacArthur’s orders, and early on the morning of April 9 sent a flag of truce to the Japanese commander, surrendering the U.S. forces on Luzon unconditionally in order to avoid “mass slaughter.”

“We have no further means of organized resistance,” said King. When he went to meet the enemy conquerors, he wore his last clean uniform and felt like General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox. Seventy-eight thousand American and Filipino troops laid down their arms, and it was the greatest defeat in U.S. Army history.

About 2,000 soldiers, Army nurses, and civilian workers of the Bataan force managed to escape to Corregidor, and the Japanese permitted many of the Philippine Army personnel to return to their homes. The rest were herded out of the peninsula on a forced march of 85 miles from Mariveles to Camp O’Donnell, a partially completed Philippine Army post on the western edge of the Luzon central plain. Many of the prisoners were humanely treated, and some rode out of Bataan in trucks and other vehicles. But the rest of the captives experienced a nightmare worse than anything they had yet seen—the Bataan death march. It was one of the most heinous atrocities of World War II.

The Japanese had expected to receive about 25,000 prisoners, but General Homma found himself saddled with three times that number, almost all of whom were sick and starving. Before being ordered into line, the captives were stripped of their canteens, rations, and personal items. Guards severed the fingers of American officers to get their West Point rings, prisoners found with Japanese money were shot, and five men too sick to make the march were bayoneted.

Some were taken by truck to Camp O’Donnell, and other prisoners—those who managed somehow to retain their health and military bearing—were treated humanely. But most were forced at bayonet point to walk much of the way under a searing April sun along sandy roads lined with foul drainage ditches. The captives marched four abreast in long columns and were given only enough food and water to survive the trek. They felt like “walking corpses,” and a doctor reported that those who survived did it “on the marrow of their bones.” Army Lieutenant Kermit Lay said many years later, “If I had to do it all over again, I would commit suicide.”

General Homma had instructed his officers to treat the prisoners well, but the death-march guards were in an ugly mood. They themselves were exhausted, hungry, and sick from the Luzon campaign, and many had lost comrades. Beatings and torture had been part of their military training, and the samurai code of bushido precluded humane treatment for prisoners. They regarded the Americans and Filipinos with disdain and so needed no orders to abuse them.

The prisoners trudged on for several days, struggling to support the wounded and sick. Men who collapsed or stopped on the roadside to defecate were beaten, shot, or beheaded with officers’ swords. Executions were frequent, and headless corpses accumulated in the roadside ditches. Filipino civilians who dared to throw rice cakes and chunks of sugar cane to the captives were shot randomly.

Eventually, barely able to stand, the prisoners reached San Fernando, where they were crammed into steaming railway boxcars for a five-hour ride to Camp O’Donnell. An estimated 750 Americans and 5,000 Filipinos perished on the march, and the dying continued at Camp O’Donnell, where more than 16,000 captives, including 1,600 Americans, succumbed to disease, starvation, and brutality in the next two months.

After the fall of Luzon, the Japanese turned their full attention to Corregidor and its 11,000-strong garrison, only two miles from Bataan. Massed enemy artillery and continuous air raids pounded the fortress for several weeks, destroying the beach defenses, damaging the water supply, and neutralizing all but three guns. The bombardment was so intense that cliffs collapsed, woods were obliterated, and the shore road was blown into the sea. The Japanese lobbed 16,000 shells at Corregidor on May 4. The island now lay “scorched, gaunt, and leafless.”

Just before midnight on May 5, 2,000 troops of Homma’s 4th Division crossed the straits and landed on Corregidor. The assault miscarried, and only about 800 men reached the shore. The American defenders met the invaders with 155mm guns and lighter weapons and inflicted severe damage on them, but the Japanese were able to carve out a beachhead and get artillery and three tanks ashore. The defenders crumbled, and by the morning of May 6, enemy troops were almost into the Malinta Tunnel system, which housed 1,000 helpless, groaning wounded. In order to avoid further vain losses, General Wainwright then sat grimly before a microphone in his tunnel office and broadcast a message of surrender.

General Homma refused at first to accept the local surrender because American and Filipino detachments were still fighting guerrilla style in remote areas of Luzon and the southern islands. So, Wainwright agreed to order a general surrender, fearing that the disarmed Corregidor garrison would be massacred. It was not until June 9 that the guerrillas, still complying with MacArthur’s orders from Australia, laid down their arms. The tragic Philippine campaign was over. The Americans lost an estimated 30,000 troops, the Filipinos about 80,000, and the Japanese an estimated 12,000.

Its outcome was a foregone conclusion from the start, but the defense of the Philippines was a tribute to the gallantry and stoicism of the officers and men involved. It delayed the Japanese strategic timetable for five critical months, during which an unready America was rallying its military and industrial resources.

The late Michael D. Hull wrote for WWII History on a number of military topics and resided in Enfield, Connecticut.

Photo in the article is incorrectly labeled “Japanese soldiers man field artillery pieces set to bombard American and Filipino defensive positions in the Philippines” It should read “Japanese soldiers around captured 155mm GPF guns of the American 301st Field Artillery after the fall of Bataan” Write me and if necessary, I can provide the background and information.

The original defensive battle plans were not particularly well thought out, mainly for lack of supplies. They were not executed well, mainly for lack of foresight by MacArthur. That the troops fought as well as they did took tremendous fortitude.