By Eric Niderost

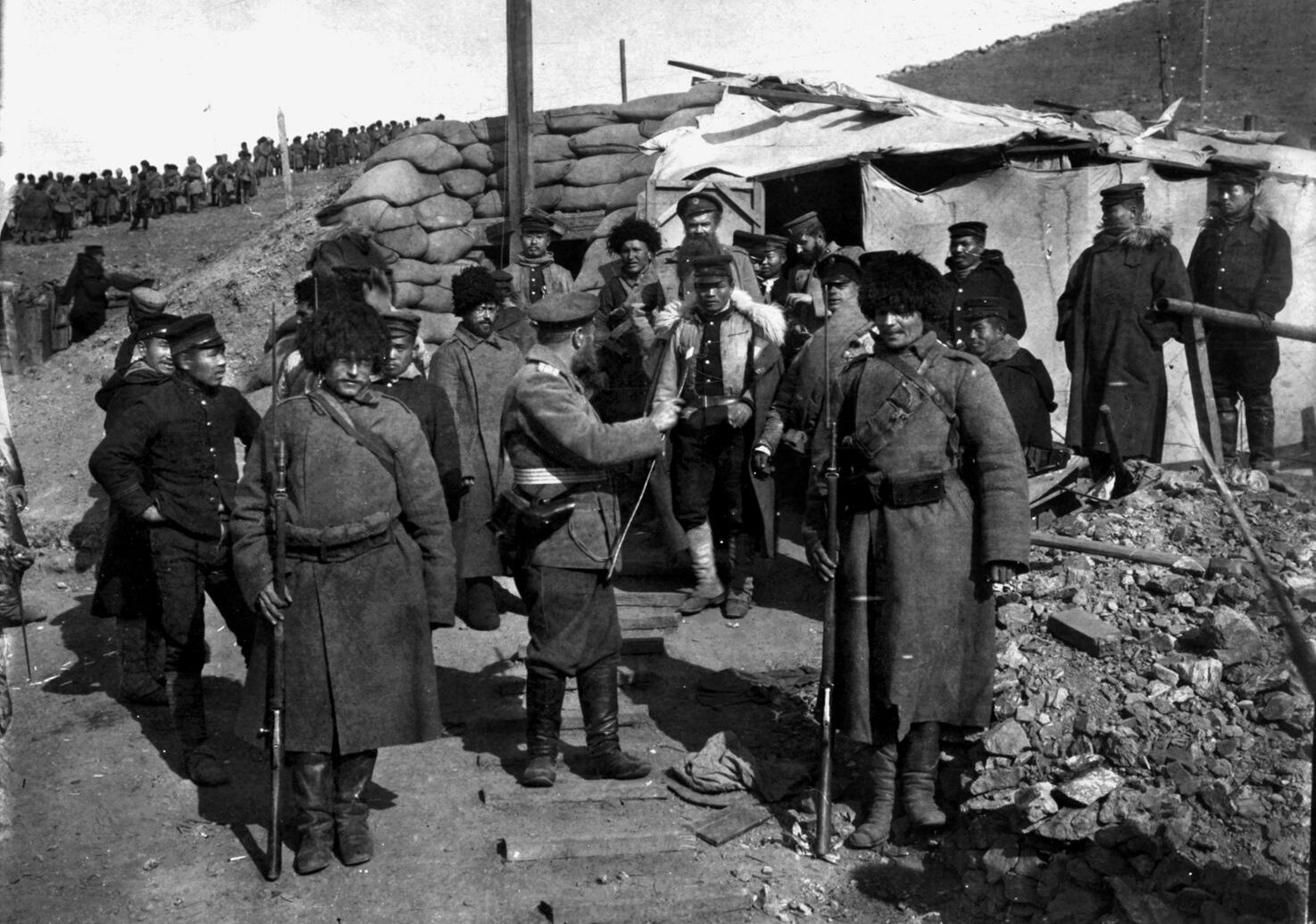

On the chilly night of February 8, 1904, the Imperial Russian Navy’s Pacific Squadron lay peacefully at anchor just outside Port Arthur’s main harbor. Part fortress, part naval base, Port Arthur was located at the tip of the Liaodong Peninsula in southern China. With the Yellow Sea to the east and the Bohai Sea to the west, it commanded the approaches to Peking (Beijing), China’s ancient capital. Port Arthur also protected Russian interests in the region, particularly its claim to mineral-rich Manchuria.

Japan also coveted Manchuria, just as it had designs on neighboring Korea. The two rival empires were on a collision course, and half-heated attempts to resolve their differences only seemed to accelerate the headlong rush to war. In early 1904, Port Arthur received word that Japan had broken off diplomatic relations, but the news scarcely lifted an eyebrow. Who would dare to attack the great fortress, a bastion of Holy Mother Russia?

Japanese Sneak Attack on Port Arthur

Seven Russian battleships were riding at anchor, including the flagship Petropavlovsk, a 12,000-ton vessel that mounted four 12-inch and 12 6-inch guns. No less than six cruisers also were on hand, along with the transport ship Angara. The cruisers Pallada and Askold probed the ocean darkness with their searchlights, a precaution against surprise attack. Vice Admiral Oskar Victorovitch Stark, the fleet commander, had ordered the searchlights utilized to guard the approaches to the Russian ships. He also commanded that each vessel’s torpedo nets be raised, but some of the ships ignored the order. Most of the crews were ill-trained, and many of the officers were arrogant aristocrats more interested in shore leave than the overall welfare of their men.

At 11:50 pm, 10 Japanese ships from the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Destroyer Flotillas suddenly appeared out of the blackness and launched a series of torpedoes at the Russian ships. Ironically, the Russian searchlights had found the Japanese ships moments before the attack began. The Japanese held their breath as long fingers of light illuminated their destroyers for a few seconds before moving on. No alarm was raised, so a relieved Captain Asai Shojiro ordered his destroyers to launch their torpedoes at once. The Russian sailors on searchlight duty apparently had mistaken the Japanese ships for returning Russian patrol vessels. There had been no formal declaration of war between the two countries, and surprise was complete.

When the night attack was over, three of Russia’s proudest ships were damaged. Pallada, Retvizan, and Tsarevitch were crippled; the latter’s bulkhead was shattered and her forward compartment flooded. Ironically, only three of the 16 Japanese torpedoes fired that night found their mark; the rest either missed or malfunctioned. It didn’t matter. Japan had struck first, a psychological blow that put the Russians badly off-kilter in the opening months of the conflict.

There were sound strategic reasons why the Japanese wanted Port Arthur. First and foremost, they hoped to wipe out what they considered a national dishonor. In 1894-1895, a newly modernized Japan had fought a war against the decaying Chinese empire. It was an easy victory, and the triumphant Japanese forced the Chinese to sign the Treaty of Shimonoseki. The pact gave Japan the Liaodong Peninsula and allowed it to occupy Korea, at the time still a Chinese vassal state. One of the victors’ first acts was to land at Port Arthur, and as soon as Japanese troops were ashore they massacred the Chinese garrison. As many as 2,000 Chinese were put to the sword, a figure that included women and children.

The Gibraltar of the East

Russia viewed the events with a mixture of jealousy and alarm. Czar Nicholas II and his ministers felt that China’s decline offered new opportunities for Russian expansion in the Far East. In the wake of the Boxer Rebellion, the various European powers were scrambling to grab choice bits of the Chinese mainland, and it was natural for Russia to stake its own claim. Manchuria was a bleak land of frigid wastes and barren hills, but underneath the windswept surface lay enormous deposits of coal, iron, and copper.

For the Russians, the real prize was Port Arthur and the Liaodong Peninsula. The hills surrounding Port Arthur shielded its harbor from the worst effects of the freezing blasts of winter wind that barreled in from the Arctic, keeping its port facilities ice free all year round. Vladivostok, the terminus of the Trans-Siberian Railway, was some 1,220 miles to the north, and its harbor was frozen solid for at least three months of the year. Accordingly, Russia joined with Germany and France to force Japan to relinquish control of the Liaodong Peninsula and return it to China. Japan yielded grudgingly to the so-called Tripartite Intervention, but the subsequent loss of face was hard to bear. Tokyo would bide its time, gather strength, and win back what had been “stolen” from Japan.

Once Japan was ejected from the region, Russia lost no time in strong-arming the Chinese into a new series of concessions. Peking agreed to a 25-year lease of Port Arthur and a rail line through Manchuria. A rail spur was also constructed that linked Port Arthur to the Trans-Siberian railhead at Harbin. Russian engineers worked hard to strengthen Port Arthur’s defenses. The goal was to make the town the Gibraltar of the East. Russia’s desire to have a warm water port, a dream that dated back as far as Peter the Great, seemed at last fulfilled.

A Fortress and a Naval Base

By 1904, Port Arthur was one of the most heavily fortified places on earth, a position that most observers thought was impregnable. It was named after Lieutenant William C. Arthur of the British Royal Navy, who sheltered there in 1860 during a raging typhoon. He described the harbor in great detail, and before long people started calling the place Port Arthur in honor of the intrepid Englishman. Port Arthur in some respects was not one city but two: an Old Town and an embryonic New Town. Old Town’s narrow, unpaved streets were lined with dilapidated warehouses, shabby hotels, and poorly built administrative and residential buildings. By contrast, New Town boasted broad tree-lined avenues and modern buildings—a visual declaration that Russia was there to stay.

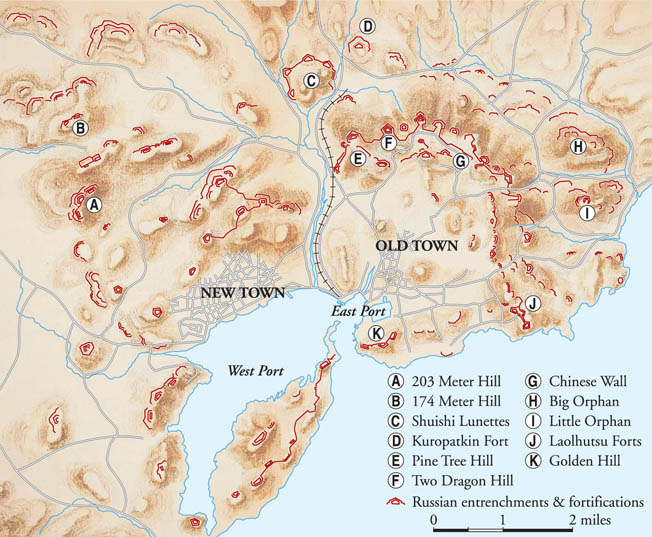

When all was said and done, Port Arthur was both a fortress and a naval base. In the East Basin of the harbor were docks, machine shops, fuel depots, and ammunition stockpiles. The Japanese would find Port Arthur a tough nut to crack. The first line of defense was a series of fortified hills that rose like a giant’s backbone against the slate gray skies. They ran in a great semicircle some 20 miles through the brownish-gray landscape, bristling with 6-inch guns and Maxim machine guns. Gaps between the forts were filled with connecting trenches and covered ways, and good roads assured an easy passage for men, guns, ammunition, and supplies.

Among the more prominent forts were Little Orphan Hill and Big Orphan Hill to the east and 203 Meter Hill, 174 Meter Hill, and False Hill to the west. Thick tangles of barbed wire were strung on the precipitous slopes, and wherever possible natural features were incorporated into the design. Big Orphan and Little Orphan Hills were steep, and the Russians had purposely dammed the Tai River to provide a natural moat at their bases. The Russians also made good use of old Chinese fortifications that once had sheltered and protected Old Town. Most prominent was the Chinese Wall, a 10-foot-high mud and brick structure that snaked its way through the western outskirts of Port Arthur. It was protected from artillery fire and featured a covered way that could be used for both shelter and communication purposes.

“Port Arthur Will be My Tomb!”

In the weeks before the siege, Maj. Gen. Roman Kondratenko and his 8th Siberian Rifles were assigned the task of strengthening the port’s defenses. Hundreds of Chinese supplemented the work force, digging into the hard earth and carting away basketfuls of soil. There was a shortage of concrete and barbed wire, so the Russians improvised with telegraph line. Kondratenko’s men also planted land mines and laid new telephone lines for better communications and fire control. Approaches to the fortifications were sown with fiendishly ingenious booby traps such as nail boards, wooden planks that bristled with a carpet of 5-inch nails, points facing outward. Since Japanese troops often wore straw sandals, the nail boards would prove particularly effective. The Russians also built trenches in the sides of steep hills and roofed them with timber supports. Once covered with earth and boulders, they seemed part of the hill’s natural slope. Loopholes and vision slits allowed defenders in the trenches to fire down upon advancing attackers and roll down hand grenades.

Lieutenant General Baron Anatole Stoessel was Port Arthur’s commander. He was a brave but incompetent officer who attempted to gloss over his flaws by issuing communiqués filled with bluster and bravado. “Farewell forever” ran one missive to a friend outside the town. “Port Arthur will be my tomb!” Stoessel enforced Draconian rules of discipline, and soldiers were flogged for drunkenness—a frequent Russian Army offense. The ill treatment of the troops caused the garrison’s morale to plummet.

For all his bombast, Stoessel didn’t really believe the Japanese were a threat. Instead, he allowed Port Arthur to function as a kind of supply depot for Russians in other parts of China, in the process diminishing precious stocks of food that his own men would need during a siege. Stoessel was supposed to hand over command to the well-respected Lt. Gen. Konstantin Smirnov while he took over the Third Siberian Corps, but Stoessel flatly refused to budge. Just before the Japanese Third Army arrived on the scene, Port Arthur had a garrison of almost 50,000 men and 500 guns. When noncombatants were added to the total, there were around 87,000 souls to feed. Food stocks seemed adequate at first, but prices on such basic necessities quickly rose.

Disaster For the Russian Navy

Japanese war plans were simple and direct. Vice Admiral Heihachiro Togo was to cripple and neutralize the Russian fleet at Port Arthur and blockade the port. His surprise torpedo attack was the first phase of the Japanese plan. Attempts to blockade Port Arthur’s harbor entrance with Japanese merchantmen met with less success. Togo remained a threatening presence off the coast. The Russians had some of the finest warships afloat, but poor training and morale neutralized their effectiveness. There was a glimmer of hope when Vice Admiral Stepan Makarov arrived at the scene in March. Gifted and charismatic, the fork-bearded Makarov instilled fighting spirit in his officers and men. On April 13, Makarov led his squadron out to seek a general engagement with the enemy. Unfortunately for the Russians, his flagship Petropavlovsk struck a mine and sank with all 600 hands on board. The loss of the admiral was a grievous blow to the Imperial Russian Navy.

A half-hearted naval breakout in August also ended in a fiasco. After a brief but bloody general engagement with Togo, the Russian ships were badly mauled. Some scattered in an attempt to escape the debacle, and one battered vessel got as far as Shanghai. Others managed to limp back to Port Arthur. The Pacific Squadron’s guns aided the port’s defense, but it was now marooned and finished as a naval force.

Besieging the Port

Meanwhile, General Takemoto Kuroki’s First Army landed in northern Korea and engaged Russian forces soon after crossing the Yalu River into Manchuria. After he easily defeated the Russians, shock waves were felt throughout the world. The fighting had been relatively small scale, but for the first time in modern history a major European power had been bested by supposedly inferior Asians. Meanwhile, the Japanese Second Army under General Baron Yasukata Oku landed on the Liaodong Peninsula, imposing itself between Port Arthur and General Alexei Kuropatkin’s Russian troops farther north. That meant, in effect, that the fortress city’s communications link to Manchuria and Russia had been effectively severed. Oku decisively defeated a Russian relief force at Telissu on June 15. Port Arthur was on its own.

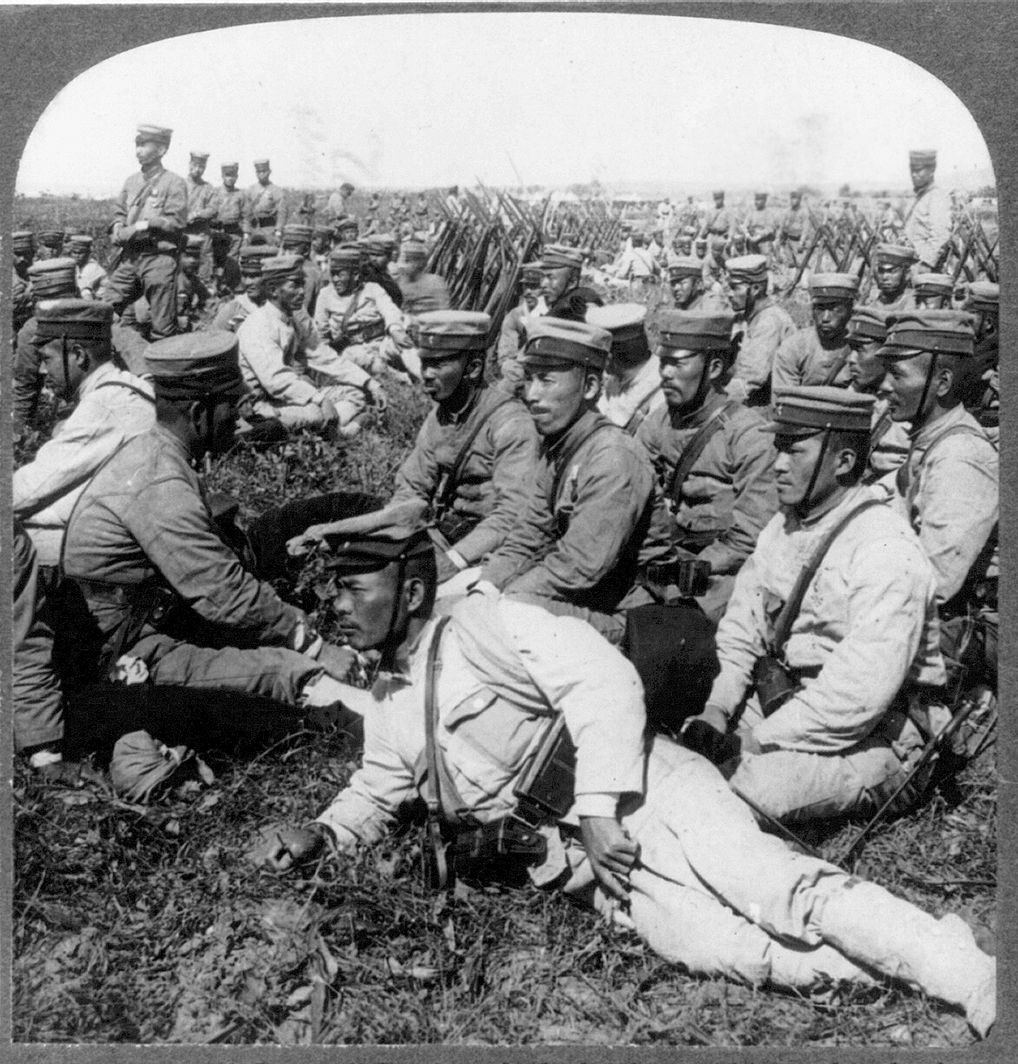

The task of actually capturing Port Arthur was assigned to General Maresuke Nogi’s 90,000-man Third Army. Nogi landed about 27 miles north of the fortress and slowly made his way southward. Port Arthur was placed on full alert, and all forts, redoubts, and emplacements were manned. The remaining Pacific Squadron ships were manned by skeleton crews after Russian blue jackets went ashore to help garrison the forts.

The formal siege opened on August 7 with a bombardment of Old Town. Inside the fortress, a church service was being held to petition divine intervention. The Orthodox priest’s fervent prayers were punctuated by the muffled rumble of distant cannons and the nearer roar of exploding shells. It was the beginning of an ordeal that would last for the next five months.

Taking Big Orphan and Little Orphan

Outside Port Arthur, Nogi decided that Big Orphan and Little Orphan Hills should be taken first. About four miles northeast of Port Arthur, these two hills would give the Japanese an excellent view of other more formidable redoubts closer to the port. The Japanese were utterly contemptuous of the Russians, so much so that they blinded themselves to the real difficulties that lay ahead. Japanese intelligence failed to get any real sense of Port Arthur’s strength, and the one or two reports that did approach the truth were blithely ignored by the high command.

Nogi, a stern old warrior steeped in the samurai tradition, was convinced that go-ahead “banzai” spirit alone would win the day. He ordered the two hills taken by frontal assault on their northwestern and northeastern sides. In that way, the Russian ships in the harbor could not provide artillery support. Japanese infantry would have to wade the swollen Tai River then clamber up the steep slopes of the hills under heavy machine gun, rifle, and artillery fire. After a preliminary bombardment that lasted about 15 hours, the infantry was ordered forward.

At 7:30 on the evening of August 7, a drenching rain fell on the struggling Japanese infantrymen as they groped their way through the pitch-black darkness, their way lighted only by the blinding flashes of bursting artillery shells and the probing fingers of Russian searchlights. Japanese engineers managed to reach the Russian dam and punch a hole in it, releasing the Tai River’s pent-up waters. Heavily laden Japanese infantry crossing the river found it tough going, and some drowned in the attempt. Most of the sodden Japanese soldiers managed to reach the base of the hills, but their ordeal was far from over. Seen from ground level, the 600-foot Big Orphan Hill looked particularly huge. Amid the carnage, one Japanese officer couldn’t help waxing poetic. “Above us the steep mountain stood high, kissing the heavens,” he wrote. “Even monkeys could hardly climb it.”

The attack stalled, but the bloodied Japanese tried again to scale Big Orphan Hill the next day. The Russian defenders resisted stubbornly, throwing boulders down onto their climbing foes. The Japanese managed to reach the crest of Big Orphan Hill at 8 the next night. The Russians at the summit stood their ground, and the fighting was hand to hand, but in the end they were overwhelmed by superior Japanese numbers. The exhausted victors proudly raised the Rising Sun flag—only to find it a magnet for artillery fire from the other Russian forts.

Little Orphan Hill fell the next day. Taking the two hills had cost the Third Army more than 3,000 casualties. This was a sobering figure, because Big Orphan and Little Orphan’s fortifications were light and their garrisons relatively small. Much more formidable works lay ahead. Undeterred, Nogi poured over his maps, scanned the horizon with his telescope, and stubbornly concluded that an infantry frontal assault would still work. On August 13, the Japanese launched a photo reconnaissance balloon that the Russians failed to shoot down. Incredibly, the aerial photos only reinforced Nogi’s plans. “The condition of the fortress,” Nogi declared, “and the troops guarding it, are, to our present knowledge, such that storming attacks need not be unsuccessful.” It was a less than confident assessment.

Fight For 174 Meter Hill

The Japanese assault would attempt to seize Wantai Ravine, in the center of the northeastern semicircle of forts, then sweep on to capture Two Dragon and Pine Tree Hills. Once they were secure, the Japanese forces would drive on through the Chinese Wall and into Port Arthur itself. The scheme bordered on insanity. No heavily fortified position had ever been taken by masses of exposed infantry armed mainly with rifles. Nogi also ignored an important event that had occurred some weeks before. On June 15, the Russian cruiser Gromobol sank Hitachi Maru, a Japanese transport ship that had been carrying heavy German-made Krupp artillery to the Third Army. These guns had the potential of pulverizing Port Arthur’s ring of concrete and steel, perhaps shortening the siege by weeks. Now they were at the bottom of the ocean.

The Japanese assault began on August 19. The Third Army’s 1st Division attacked 174 Meter Hill, three miles north-northwest of Port Arthur, a site that commanded the approaches to 203 Meter Hill. The 174 Meter Hill defenders were led by Colonel Nikolai Tretyakov, under the overall command of Kondratenko. The two men stood out as competent, imaginative, and resourceful officers, and together they made a formidable team. To strengthen 174 Meter Hill’s defenses, the promontory had been ringed by three lines of trenches. The hill was defended by the 5th and 13th East Siberian Rifle Regiments and two companies of sailors. The Japanese dream of easy victory was going to be quickly shattered.

The Japanese came forward in broad daylight, as if defying fate. They managed to cut through the barbed wire at the base of 174 Meter Hill and gain a foothold on the northern slope. Again the Russians contested every inch of ground, but by midmorning the first trench had fallen to the Japanese. After two hours the second trench also fell, but the third trench and the crown of the hill still held firm.

Kondratenko sent in two more companies and ordered the soldiers to repair works that had partly caved in from Japanese artillery fire. More reinforcements were desperately needed, but just when the crisis was at its height Lt. Gen. Alexander Fok arrived at 174 Meter Hill. He was a headquarters general, another one of those officers who tended to make heroic pronouncements he could not back up. “Hill 174 must be held at all costs!” Fok declared, as if the hard-pressed officers didn’t already realize the obvious. Paradoxically, Fok refused to endorse Kondratenko’s request for more men. Without help, the Russian defenders began to lose hope. Men started to fall back without orders, although a hard core of stubborn veterans still held the summit. The trickle of retreating men became a flood, and despite his best efforts Tretyakov could not stop the flow.

At times only 50 yards separated the opposing forces. Bursting artillery shells eviscerated men and buried trenches with cascades of earth, rubble, and human flesh. When night fell, the battle for 174 Meter Hill took on a surreal quality. British war correspondent Frederick Villiers wrote with a painter’s eye of the “warm incandescent glow of the star bombs, the reddish spurts of the cannon mouths, and the yellowish flash of an exploding shell.”

16,000 Japanese Casualties

The hill finally fell to the Japanese, but an even bloodier clash was occurring three miles away at the Waterworks Redoubt. The area was seamed with dried up watercourses and thick patches of millet that grew 15 feet high and provided additional ground cover. Unsurprisingly, the Japanese found Waterworks Redoubt tough going. The Russians had fiendishly electrified the wire entanglements, and many Japanese soldiers were shocked to death.

The attackers found ways of getting through the electrified wire. One method was to use special wire cutters whose handles were covered in bamboo. Once through the wire, the sweating Japanese infantry faced a firestorm of shot and shell. Chattering machine guns cut bloody swathes into the advancing soldiers, and bursting artillery shells took off heads and limbs with horrifying ease. Soon, most of the lower slopes were speckled with Japanese bodies. When Lieutenant Tadayoshi Sakurai recalled the attack later, he described it with a mixture of poetry and hard-headed reality. “We lived in the stink of rotting flesh and crumbling bones,” he wrote, adding, “We still were offshoots of the genuine cherry trees of Yamato!”

At the nearby Pan Lung forts, the story was much the same. Ravines filled up with Japanese dead, so much so that advancing ranks coming behind them were forced to tread on the corpses of their fallen comrades. Finally the Japanese broke into East Pan Lung fort, where the fighting was hand to hand. The Russians had a motto: “Pulia duraka no shtyk molodets,” meaning, “The bullet is an idiot, but the bayonet is a fine fellow.” They excelled in this kind of brutal, close-in fighting.

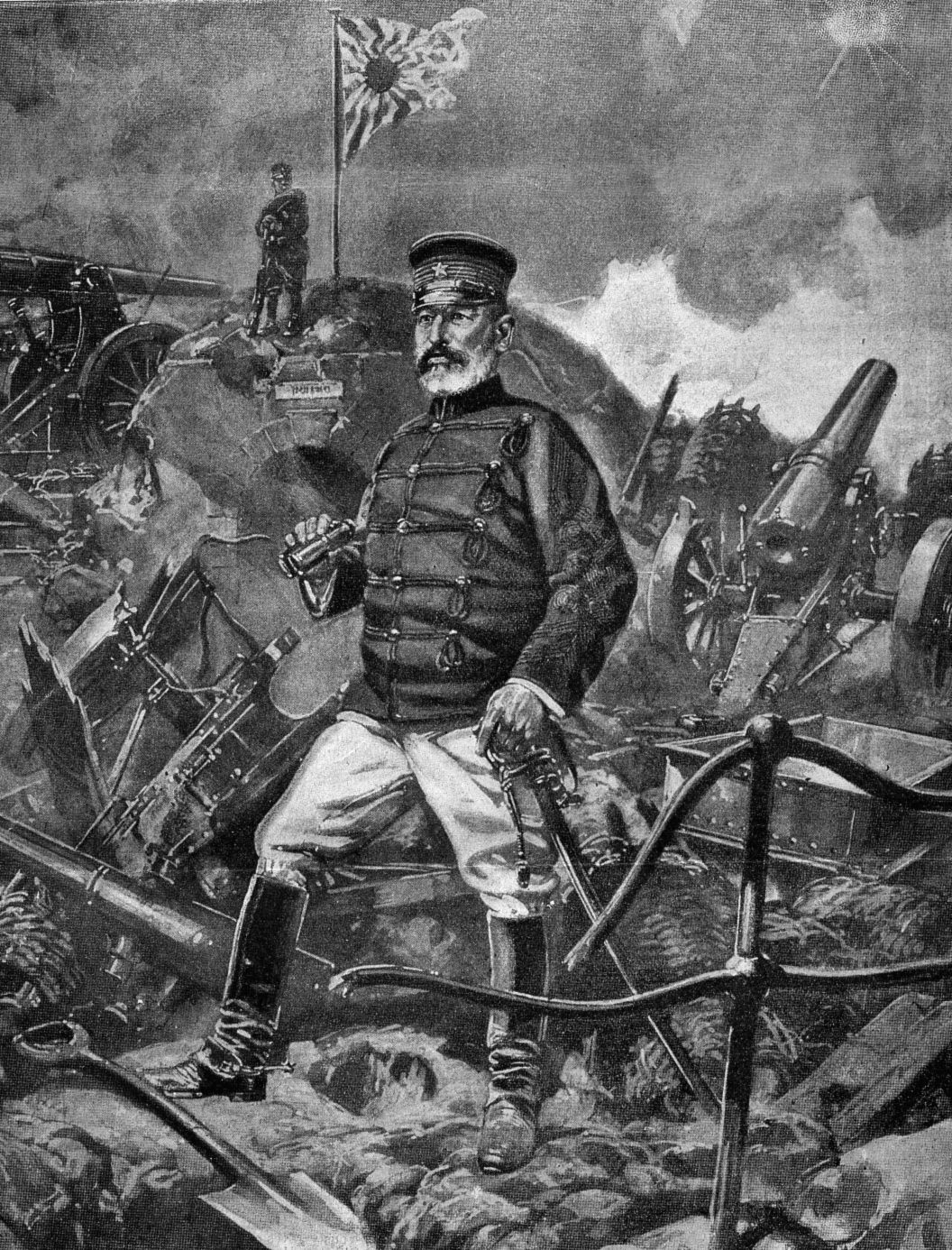

West Pan Lung fell on August 22, and East Pan Lung soon after. The two small forts, along with 174 Meter Hill, had cost the Japanese around 16,000 casualties. Even worse, the main Russian works were still as strong and defiant as ever. When he looked at the butcher’s bill, Nogi was unmoved. The Japanese 7th Regiment had started the attack with 1,800 men; by the time East Pan Lung was taken, only 200 remained alive. Even Nogi had to admit that rifles and samurai spirit were not enough against concrete, steel, and machine guns.

A Slow but Steady Siege

Traditional siege operations began August 25. Japanese sappers dug siege trenches toward Russian forts, a technique that went back the 17th century, hoping that their comrades could burrow under Russian walls, secretly place subterranean charges beneath the works, and blow gaps in them before the Russians realized what was going on.

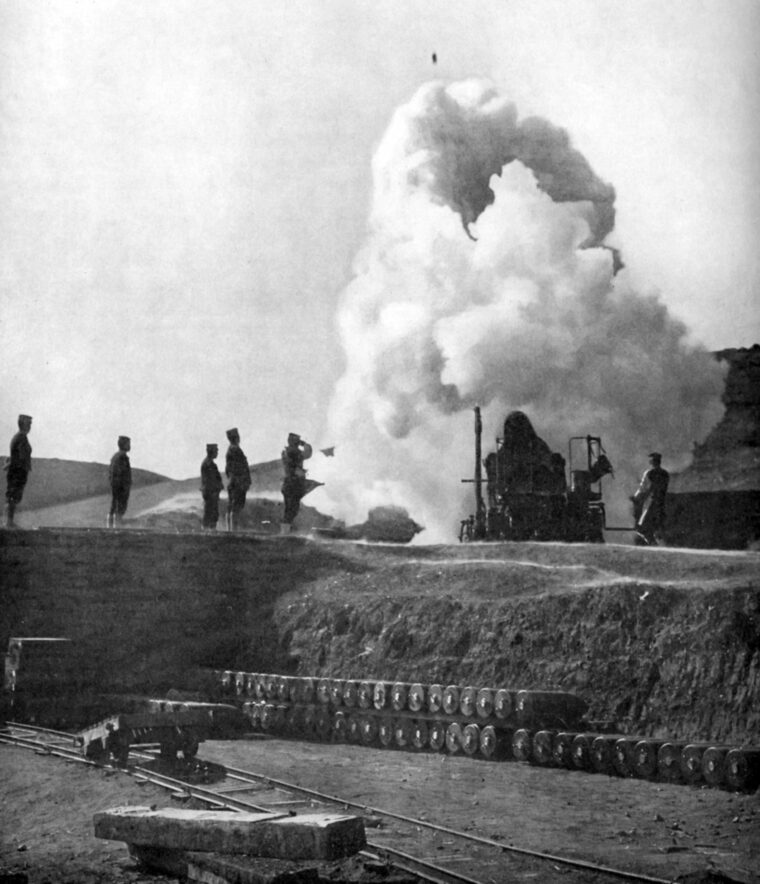

Prospects brightened for the Japanese as time went on. Reinforcements poured in from Japan, and another shipload of gigantic 11-inch siege howitzers arrived to replace the ones that previously had been lost. These howitzers, dubbed “Osaka babies,” weighed 23 tons each and could hurl 500-pound shells some 5½ miles. In October, these behemoths started shelling Port Arthur and its surrounding forts.

Japanese progress was slow but steady. Waterworks Redoubt fell on September 16, and Temple Redoubt was in Japanese hands soon after. But Nogi’s blind spot was 203 Meter Hill, which in many ways was the key to the whole Russian defense. If the Japanese could take the hill, they would have a splendid and unobstructed view of Port Arthur and its harbor. The remaining vessels of the Imperial Russian Pacific Fleet would be sitting ducks, unable to escape from the rain of shells launched from 203 Meter Hill.

Human Wave Attacks on 203 Meter Hill

By late November, Nogi was under increasing pressure to take Port Arthur. The Russian Baltic Fleet was on its way, making an epic 18,000-mile journey from Europe to take on the Japanese Navy. Port Arthur had to be taken before the Baltic Fleet could come to its aid. The Russians still had powerful field forces to the north, and the prolonged siege tied up Nogi’s Third Army, troops that were badly needed elsewhere.

The battle for 203 Meter Hill was a titanic struggle that would last several days. Both sides knew that the hill was the key to Port Arthur. Actually, 203 was not one hill but two peaks, each having fortified citadels protected with heavy timbers and armor plate. Two lines of rifle trenches encircled the crest, and tangles of barbed wire blocked access to the top. The hill’s garrison consisted of Russian soldiers and sailors under the command of the redoubtable and seemingly ubiquitous Tretyakov. Food stocks were low on the hill, and the men’s main diet was horse or mule meat supplemented by an occasional fish taken from a nearby stream.

Once again the Japanese came forward in human wave attacks, only to be met by heavy artillery and rifle and machine-gun fire. A Russian battery of four 6-inch guns worked with a will, perspiring gunners ramming fresh shells into the breeches with each recoil. The hills changed hands several times; both sides displayed incredible valor and devotion to duty. Eventually, some Russian soldiers began to crack under the strain. When the battle-grimed defenders began to falter, Tretyakov used every means possible to rally them; occasionally he had to use the flat of his sword if men hesitated to obey. At one point, the colonel pointed to a Japanese flag that had been planted on the crest of the hill. “Go and take it, my lads!” he shouted, and his men scrambled up the slope to obey.

After a seesaw battle, the Russians were still holding on to 203 Meter Hill’s two peaks. The Japanese abandoned the costly human wave tactics and brought up 11-inch howitzers. More than 1,000 shells hit the hill in an almost continuous barrage that lasted throughout the day. Russian fortifications atop were pulverized into splinted wood and concrete rubble. A large cloud of dust covered the peak like a funeral shroud.

By this time, Russian soldiers and sailors were clinging to the shattered remains of their fortifications with a mixture of courage and grim fatalism. Most of their officers were dead, and Tretyakov was wounded. Finally, at 10:30 am on December 5, the Japanese overran 203 Meter Hill. Only a handful of bloodied Russian survivors remained. The assault had cost the Japanese a staggering 14,000 casualties, while the Russians lost 6,000 men.

The Japanese wasted little time in manhandling their 11-inch howitzers up 203 Meter Hill. The view from the crest was perfect, and hitting the Russian ships below was like shooting fish in a barrel. Within a few days, virtually all remaining vessels were destroyed or badly damaged. Worse was to come. One by one, the remaining hills were captured. Fort Chikuan was blown sky high by an underground mine that the Japanese had placed there.

The Fall of Port Arthur

By mid-December, it was clear that Port Arthur could not hold out for much longer. Food was becoming scarce, and disease was starting to spread. Many in the garrison were ill with scurvy, while others battled dysentery. Most officers still refused to surrender, and there were heated arguments over which course of action to take. Smirnov pointed out that ammunition was low, with just enough to repel two major assaults. “When the big gun ammunition has run out,” he warned, “we shall still have 10,000,000 rounds of small arms ammunition. After that, we shall have our bayonets.” By late December, most of the major forts and redoubts were in Japanese hands. Port Arthur had become militarily untenable.

On January 1, 1905, Stoessel dispatched an officer to Nogi under a flag of truce, proposing to surrender Port Arthur. According to the terms of the capitulation, the surviving Russian soldiers would become prisoners of war, but their officers were given the option of going into captivity alongside their men or being released on parole. Few officers chose to become POWs.

A High Cost For Victory

For the Japanese, the cost of victory had been very high. The Third Army had sustained at least 60,000 dead and wounded, and probably many more. The Japanese also had their problems with sickness, inevitable during siege conditions. Thousands succumbed to beriberi triggered by malnutrition. The Russians had fought well under the circumstances. It was said that Russian troops in the Far East were mediocre at best, and fear of revolutionary uprisings had kept Guards regiments and other elite units at home. Yet the scorned Siberian regiments, aided by sailors, had performed prodigious acts of valor on a daily basis.

Port Arthur was a dress rehearsal for the catastrophic world war a decade later. The siege employed machines guns, bolt-action magazine rifles, rapid-firing howitzers, massive artillery, barbed wire, and trenches. Japanese artillery batteries were coordinated by a central fire-control command linked by field telephones. European military leaders ignored the lessons of the century’s first major war at their own peril—and that of their foredoomed soldiers on the Western Front.

As feared, Russia’s humiliation sparked an abortive revolution that foreshadowed the eventual fall of the czar in 1917. For Japan, the capture of Port Arthur marked the beginning of an aggressive nationalistic phase during which the island nation attempted to create its own empire on the Asian mainland. Korea was annexed in 1910, and by the 1930s Japan had conquered Manchuria and was pressing southward into the heart of China. These overt acts of aggression eventually set Japan on a collision course with the United States begun, like Port Arthur, with an underhanded sneak attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. What had begun victoriously at Port Arthur ended ignominiously with Japan’s utter defeat in 1945. As the Bible says, “Pride goeth before destruction, and an haughty spirit before a fall.” The Japanese military was nothing if not proud.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments