By Robert Whiter

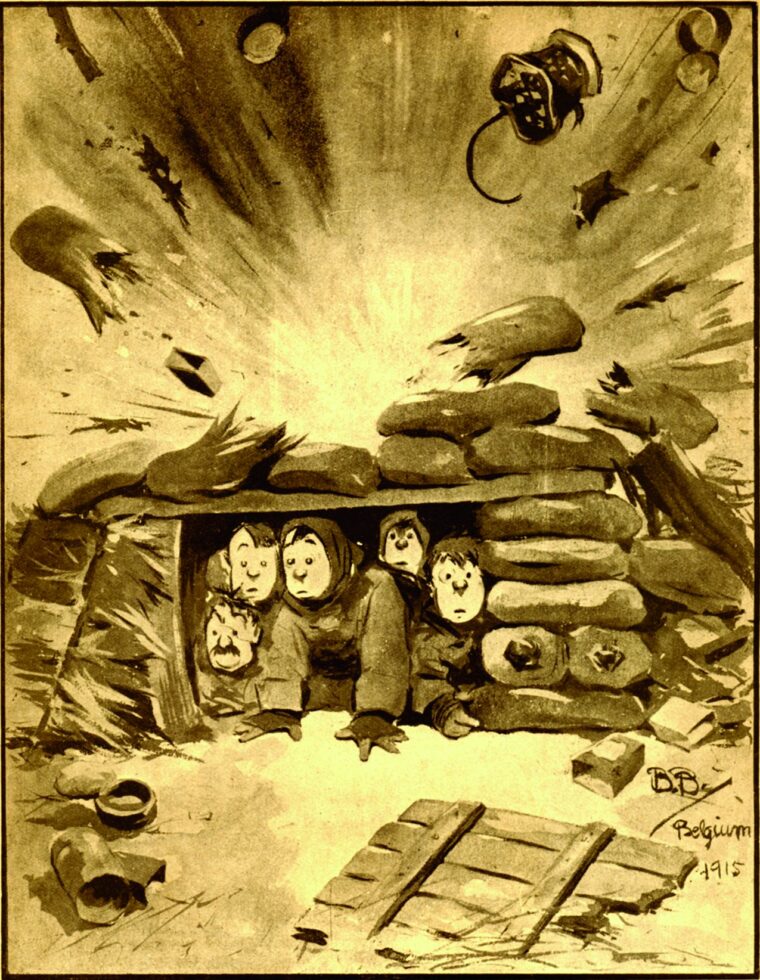

You should send that into one of the illustrated papers or magazines,” said a young subaltern, looking over the shoulder of an officer who was sitting in front of a makeshift table finishing a pen-and-ink drawing. “That’s what I’ve been telling him about all those other drawings he’s been doing these last few weeks,” chimed in another officer. The drawing in question depicted a group of men huddling together in a dugout with a shell exploding on the roof. The caption read: “Where Did That One Go To?”

The artist in question was Lieutenant Bruce Bairnsfather, stationed with his regiment, the 1st Warwicks, in front of Ploegsteert, Belgium, facetiously known to the British Army as Plugstreet Wood, barely 200 yards from the German trenches. The date was December 1914. Bairnsfather and his brother officers were billeted in a ramshackle old house, its roof and walls offering little shelter from the winter weather—let alone the enemy’s fire.

To create some form of protection, Bairnsfather and another lieutenant started to dig a cellar under the floor of the old house. He alternated this backbreaking task with drawing pictures on the walls and on any piece of paper he could find. Ever since he could hold a pencil, Bairnsfather had aspired to be an artist, but apart from selling a couple of designs for posters, he had been forced to rely on his salary as an electrical engineer. Although he came from a military family (his father was an officer in the British Army) and had served a stint in the peacetime army, Bairnsfather wasn’t really a soldier at heart. But returning from an electrical job in Canada, he found his country at war with Germany and enlisted in his old regiment in August 1914.

In January 1915, when his battalion was taken out of the line and sent for a rest to a farm near Neuve Eglise, Bairnsfather finally had the chance to make a wash drawing of “Where Did That One Go To?” Sorting through a pile of old magazines lying about at the transport farm, the artist came across a copy of Bystander. Its contents and presentation convinced Bairnsfather that it was the periodical most likely to accept his work. He carefully rolled up the drawing in a protective sheet of paper and put it in the mail.

Not long after that, Bairnsfather’s unit was ordered to Wulverghen, which was located near Messines Ridge, made famous later in the war when the British Army exploded a large mine under the German trenches. After a few weeks in line, Bairnsfather’s unit came out and rested at a farmhouse on the Momerin Road. The battalion arrived at the billet in pitch darkness and pouring rain. Once under cover, Bairnsfather saw an NCO sorting through the mail by the light of a flickering candle. Among the pieces was a letter from the editor of Bystander saying that Bairnsfather’s drawing had been accepted and that he would be pleased to see others.

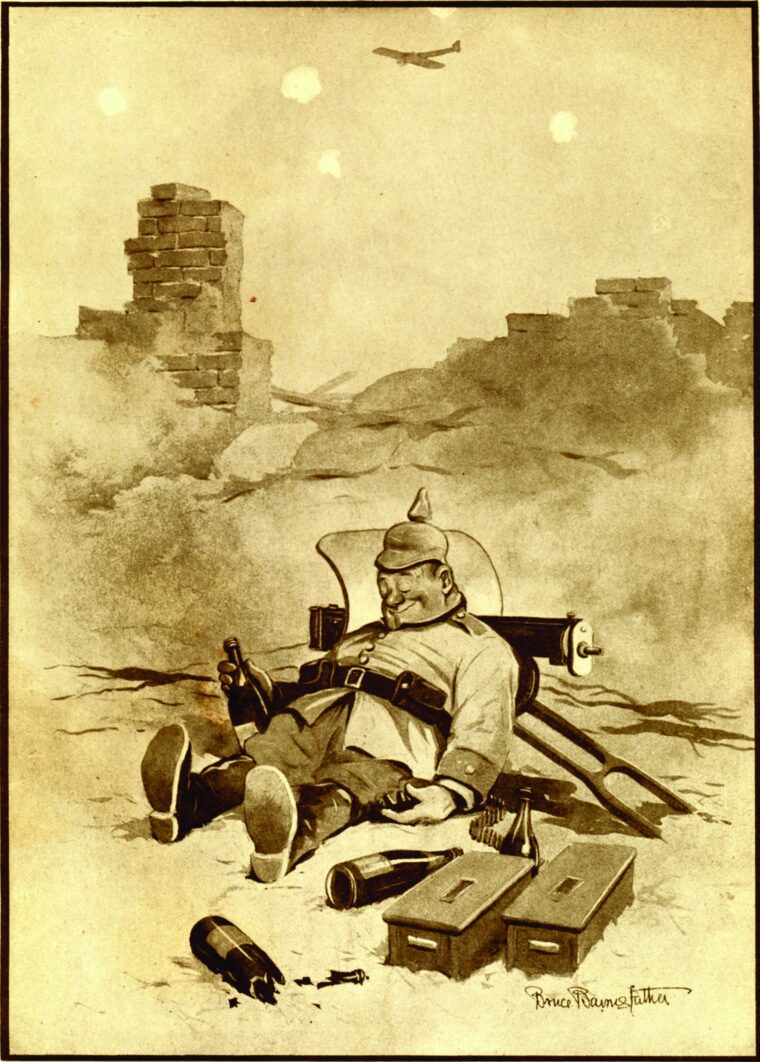

Bairnsfather’s cartoons began appearing regularly in the magazine under the title “Fragments from France.” Not only did they make the British and their allies laugh, they even found an appreciative audience with the enemy. Many of Bairnsfather’s drawings were found pinned up in German dugouts, and on one occasion a letter of appreciation written by an officer of the vaunted Uhlans was received at Bystander’s offices.

Bairnsfather returned to doing poster work. One poster in particular hit the mark—a tough-looking British Hercules behind a machine gun bearing the legend, “Beecham’s Keep You Fit.” Unfortunately, the young lieutenant was neither mentally nor physically fit himself, even after a fortnight’s rest at the farm. He was depressed and overwhelmed by the horror of the war. Every day saw fresh corpses being brought back to the graveyard. Still, he managed to draw a new picture entitled “They’ve Evidently Seen Me.” A certain Major Lancaster saw it and asked Bairnsfather to draw him a copy. The artist was only too happy to oblige. A third drawing of the picture, made at a small farm between Wulverghen and the Messines Ridge, was sent off to Bystander. By this time, news of Bairnsfather’s artistic prowess was spreading throughout the Army, and he was in constant demand to decorate the soldiers’ billets. This was facilitated by the persistent shelling by the Germans, which compelled the British to take cover during daytime.

Under the less than ideal circumstances, Bairnsfather was able to accept a commission from an officer of the Dublin Fusiliers who wanted him to draw some “colonel pictures” on the white plaster walls of his room. Soon the artist found another letter from Bystander’s editor accepting “They’ve Evidently Seen Me.” The relative calm before the storm helped restore Bairnsfather’s shattered nerves. But soon the whole of the 10th Brigade was sent away under sealed orders to Ypres, known far and wide as the worst spot on the Western Front. The pouring rain and constant German shelling contributed to Bairnsfather’s miserable existence. In later years, he remembered how, as a young lieutenant, he sat in the middle of a field, a waterproof sheet covering his head, watching the beautiful Cloth Hall go up in flames.

When word came that the Germans had breached the line at the St. Julian, the brigade was sent to help stem the enemy’s advance. It was a thankless task, and Bairnsfather’s company was right in the thick of it. There the Germans launched the first gas attack of the war, and its effect on the unprepared British and French troops were terrible. Bairnsfather would remember the gas attack simply as “a nightmare of horror.”

In his case, the nightmare was brought to a close by a bursting shell that blew him into the air. When he regained consciousness, Bairnsfather found himself in a hospital in Boulogne. After a short spell, he ended up in the Kings College Hospital, London. His days as a front-line soldier were over. As soon as he left the hospital as a convalescent, Bairnsfather gathered his art materials together and returned home to Bishopton, near Stratford, where he spent his recuperation working on more pictures for Bystander. A representative of the magazine called. Apparently they had received shoals of congratulations from readers, several even wanting to buy the originals. They upped Bairnsfather’s fee from £2 to £4 a week. After a month at home, the artist’s health improved tremendously. During a visit to the Crown Hotel in Warwick, the barmaid showed him a newspaper containing the list of promotions—he was now a captain.

Despite damage to his eardrum, the Medical Board pronounced Bairnsfather fit for light duties, and he was sent to the Royal Warwickshire Depot on the Isle of Wight. There he was put in command of 200 men, mostly from the Midlands. They were the colorful rural types he had served with previously, and a new character began to emerge in his work—a crusty figure in a balaclava helmet with a walrus moustache. When a fellow officer asked him who the figure was, Bairnsfather replied without thinking, “Oh, that’s Old Bill.” Thus was born his most famous character. Over the years there would be many claimants professing to have been the original Old Bill. In reality, Bairnsfather first had drawn Old Bill’s likeness on the walls of Stratford Technical College during his school days.

The new character proved so great a morale booster that the War Office was besieged with requests from France, Belgium, Italy, and eventually the United States to allow Bairnsfather to tour the various war fronts. The British brass suddenly woke up to the fact that they had a winner in the artist-captain and made him an “officer cartoonist” in the Intelligence Department. Subsequent tours were a great success. During a visit to Verdun, Bairnsfather was personally welcomed and shown around the battered example of French resistance by General Charles Mangin himself. From 1916 until the armistice in 1918, Bairnsfather rode a crest of popularity. Bystander published reproductions of his work in a variety of shapes and sizes—even packets of postcards.

Bairnsfather contributed a scene based on his cartoons entitled “Flying Colors” to a revue at the London Hippodrome. This was followed by another show called “Bairnsfatherland,” with actor-singer Ivor Novello of “Keep the Home Fires Burning” fame doing the music. Bairnsfather also wrote a script for a stage show called “The Better ‘Ole.” It was a great success, but Bairnsfather was not a good businessman. In spite of his fame, he received only a token of the profits.

With the American troops now on the Continent, the U.S. propaganda unit wanted Bairnsfather to do what he had done for the British, French, and Italians. He set off for France again, this time the American sector, arriving at Neufchateau to a great welcome. The American commander, General Clarence Edwards, already had a collection of the artist’s cartoons and at once invited Bairnsfather to dinner. The artist immediately felt at home among the friendly Americans and resolved to visit their country at his earliest opportunity. Following the success of Bairnsfather’s tour of the American front and “The Better ‘Ole,” arrangements were made for the play to open in the United States.

Bairnsfather arrived in New York aboard the White Star Liner Adriatic to a tremendous welcome. Accompanied by Hugh MacIntosh, an Australian businessman, he booked into the Astor Hotel on Times Square. But the busy round of talks and lectures, meeting famous people, signing programs, attending rehearsals, and making drawings for the various organizations to sell or raffle soon played havoc with his delicate health. Bairnsfather’s damaged left ear began bothering him again, and a doctor advised him to take the next ship home. Following the doctor’s advice, he boarded the troopship Ordnance with a contingent of American troops bound for France. In spite of his indisposition, Bairnsfather did his best to join in the fun aboard ship, drawing a picture that raised £100 for the seamen’s orphanage and completing the final chapters of his book, From Mud to Mufti. As the ship approached Mersey, rumors of the armistice were already in the air.

During World War II, Bairnsfather again put his artistic talents to good use for the Allies, contributing comic drawings to the American Armed Forces newspaper, Stars and Stripes, as well as Life and Collins magazines. In 1942 he was appointed official cartoonist for the American forces in Europe. Wearing an American captain’s uniform, he was stationed in Northern Ireland, where he drew murals on the mess and billet walls. When visiting the base, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s wife, Eleanor, enjoyed a hearty laugh over one of the artist’s cartoons drawn on the wall of the lounge.

In 1943 Bairnsfather was attached to the 305th Bomber Group of the American 8th Air Force, stationed at Chelveston. Many U.S. bombers left on runs with their noses decorated with the artist’s designs. He became friendly with squadron commander Colonel Curtis LeMay. When Bairnsfather died on September 29, 1959, from acute renal failure following the removal of his bladder, LeMay, now a general, stepped in and helped the artist’s daughter, Barbara, with expenses so that she could attend her father’s funeral in England. “It would not be accurate to say that Bruce Bairnsfather was the Bill Mauldin of World War I,” said LeMay. “He was a lot more than that.”

Bairnsfather’s memorial plaque in the Gardens of Remembrance reads, “In loving memory of Captain Bruce Bairnsfather, 1st Royal Warwickshire Regiment, Creator of Old Bill.” Two other famous people served in the same regiment: British Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery and A.A. Milne, creator of Winnie the Pooh.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments