By Frank Johnson

While the Battle of Britain raged and a German invasion was feared in the sunny, tense summer of 1940, Prime Minister Winston Churchill took time to create an organization that would exemplify his offensive spirit, his love of gadgets and innovations, and his use of cronies. That July, he set up the Combined Operations Command to develop seaborne hit-and-run raids on Nazi installations in occupied Europe and to press forward with research on “all forms of technical equipment and special craft.” The first fruit borne of the new headquarters were the all-volunteer British Commando brigades, which soon gave rise to the U.S. Rangers.

Combined Operations also was responsible for the early development of two of the most effective devices of World War II—the prefabricated concrete Mulberry harbors and PLUTO fuel pipelines set up to supply the Allied armies in the June 6, 1944, Normandy invasion. They were ranked along with the foremost British military inventions, such as tanks, aircraft carriers, radar, jet engines, and penicillin. Other more bizarre projects, however, failed to materialize.

Churchill appointed retired Admiral Sir Roger Keyes, a World War I hero, to head Combined Operations. He rapidly organized a number of Commando raids, but most were hampered by poor intelligence and planning.

Admiral Keyes antagonized fellow military leaders and insisted on direct access to Churchill, so he was booted out in October 1941 and replaced by the handsome, dashing Lord Louis Mountbatten, a Royal Navy captain, radio specialist, and cousin of King George VI.

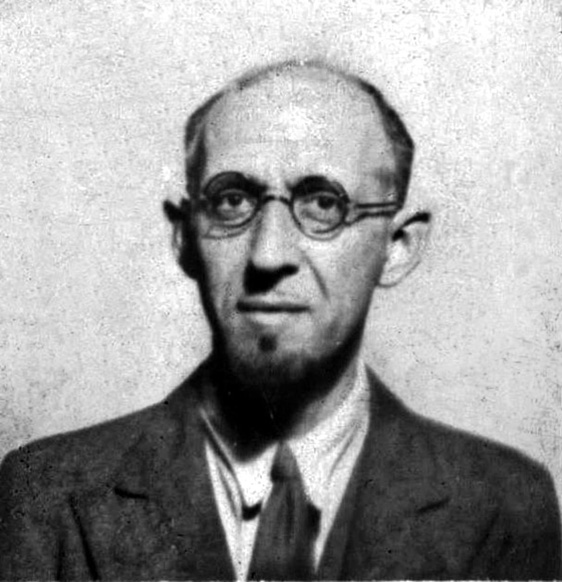

A destroyer veteran who had been waiting to take command of the carrier HMS Illustrious, Lord Louis shared the prime minister’s zeal for “dash, the unexpected, the use of novel gadgets,” and matched Churchill “in his relish for new and improbable devices.” Mountbatten marshaled a disparate cadre of “back-room boffins” (scientific advisers) and theoreticians that included South Africa-born Baron Solly Zuckerman, a strategist and authority on the biological effects of bomb blasts; Sir Malcolm Campbell, the engineer and record-breaking car and motorboat racer; Irish-born, charismatic Professor John D. Bernal, a crystallographer and lifelong Communist, and his friend, Geoffrey N. Pyke, an antisocial, inventive genius and the most eccentric British personality of the 1939-45 war.

Tall, gawky, and wild-eyed, Pyke rarely bathed, shaved, or cut his hair. He wore spats instead of socks, a soiled gray homburg, a rumpled, stained suit, and no necktie. He was jealous and suspicious and widely disliked. Yet he kept as many as 60 books at his bedside at one time and remembered everything he had read. Ideas always crowded his head. The London Times described him as “one of the most original, if unrecognized, figures of the present century.” Bernal believed that he was “one of the greatest geniuses of his time,” and a two-column Time magazine obituary called him “everybody’s conscience.”

Among his accomplishments, Pyke was responsible for the invention of a tracked, amphibious truck, fathered the creation of a highly effective Allied assault force, and helped devise the most ingenious naval weapon of the war, though it never saw action.

Geoffrey Nathaniel Pyke was born in 1894, the son of Lionel E. Pyke, a descendant of Dutch Jews. When his father died at the age of 44, the boy’s strong-minded, erratic mother decided that he would be sent to Wellington College in Crowthorne, Berkshire, which sent most of its graduates to the nearby Royal Military College at Sandhurst.

When World War I broke out in August 1914, the young man decided to become a journalist. He haunted the newspaper offices on Fleet Street, announcing that he was one of the world’s greatest reporters. His persuasiveness resulted in the Daily Chronicle hiring him, but agreeing to pay only his expenses.

After shrewdly buying a forged American passport to get him through Sweden, Pyke traveled to Germany. Six days after reaching Berlin, he was arrested by the police, who did not know what to make of him. He spent four months in solitary confinement, where he persisted in lecturing his warders on military tactics. Denied writing materials, he spent his days mentally solving mathematical problems and sharpening his powers of deductive reasoning. In 1915, he was sent to the big Ruhleben civilian prison camp, where he shared a smelly stable with 300 other men.

During the winter of 1915-16, Pyke recruited a fellow German-speaking prisoner, Edward Falk, and they came up with a plan after studying the camp schedule. Of 72 escape attempts from Ruhleben during the war, theirs was one of only three that were successful.

Life was unsettled for the restless Pyke after the war. He tried his hand as a stockbroker, became a successful metal trader, although he had received no technical training, and founded a school with such radical principles that it drew international attention.

Ideas poured from Pyke during the interwar years, and he captured the imagination of a few intimates who spread his concepts throughout the country. Alarmed by the rise of Nazism, he created a worldwide propaganda group in defense of freedom.

As war threatened in Europe in the late 1930s, Pyke came up with another plan which aroused wide interest. Pointing out the devastation that bombing would inflict on cities, he proposed that the big chalk hills in southern England be excavated to shelter large numbers of people. Some experts said later that if his plan had been accepted, thousands of lives could have been saved during the World War II air raids.

War came, as Pyke had long feared, and in 1940 he started drawing up a set of memoranda designed to clarify its true aims. He prophesied a Europe divided between East and West and predicted that the region would ultimately be dominated by the East. He also sent a memorandum to the War Cabinet advancing the use of a new military strategy. Pyke suggested that a small but tough British force could defeat a superior number of Germans if provided with the type of machinery which would give it versatility and speed.

The plan gained Pyke a valuable ally in Conservative politician Leo Amery, a former First Lord of the Admiralty and colonial secretary and a member of Churchill’s War Cabinet. Amery tried vigorously but vainly to sell Pyke’s plan to the War Office, so he submitted it in desperation to the new Combined Operations Headquarters headed by Admiral Keyes. Mild interest was shown, but it was rejected.

Things began to look up for Pyke, however, when Mountbatten took the helm of Combined Operations, and Amery put the two men in touch with each other. It was a shock for the immaculate Lord Louis when the unkempt Pyke visited his headquarters, but he tactfully listened to his ideas and was intrigued when Pyke announced, “I’ve got a plan here whereby a thousand British soldiers can tie down a force of a half a million Germans.”

Mountbatten took him on as civilian director of combined operations programs at the big salary of 1,500 pounds. The post eventually secured Pyke the respectful attention of Churchill, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and General George C. Marshall, U.S. Army Chief of Staff.

The first plan Pyke offered to Mountbatten was keyed to the invention of a vehicle — a fast, armored sled—which would travel rapidly and reliably over snow. He had few practical suggestions for its creation but considered that it presented no more of a challenge than had the development of the tank in World War I. Pyke believed that such a vehicle was needed because almost 70 percent of Europe lay under snow for five months of the year.

The vehicles, Pyke told Lord Louis, could carry small groups of specially trained troops to attack bridges, tunnels, trains, rail tracks, and power plants in snow-clad countries, such as Norway, which had been under the Nazi yoke since April 1940. Mountbatten was impressed with this new concept of warfare, and Churchill lent encouragement.

Mountbatten studied Pyke’s highly detailed, 54-page plan, and the result was Operation Plough, which called for hand-picked troops to be air-dropped into Norway, set up a glacier base, and use the sleds for hit-and-run sabotage raids against the hydroelectric stations which were critical to the German war economy. The enemy, Pyke pointed out, would be forced to send troops to retaliate and thus deplete their strength in other areas.

Lord Louis briefed Churchill on the plan at a meeting on April 11, 1942, to discuss the general strategic question of an invasion of continental Europe. It was attended by President Roosevelt’s trusted envoy, Harry Hopkins, and General Marshall. The prime minister was as impressed with Pyke’s project as Mountbatten. It was agreed that America would manufacture the “armored fighting snow vehicles” and that Pyke should go to Washington to work with Marshall, who categorized him as “a very odd-looking individual” who “talks well and may have an important contribution to make.”

Pyke was flown to Washington, where he conferred with Lt. Gen. Joseph T. McNarney, Marshall’s able, hard-headed deputy chief of staff, and other officers for several weeks. But Pyke became frustrated at the War Department. His slovenly appearance and abrasiveness shocked many, and McNarney developed an intense dislike for him. The Americans insisted on making a thorough investigation into the physical nature of snow, and, while assuring Pyke that they would bring his plans to fruition, they agreed unanimously in private that the idea was worthless and should be abandoned. The lack of enthusiasm irritated Pyke. He became verbally abusive at times, was barred from some meetings on security grounds, and cabled Mountbatten that he was being “sold short.”

After initially supporting Project Plough, the Norwegians decided it would almost totally destroy their country’s industry, so Mountbatten decided eventually that it should be sidetracked. Yet Pyke’s plan led to two breakthroughs for the Allied war effort.

The first was the Studebaker-built M-29 Weasel, a 2.5-ton tracked amphibious cargo carrier with a two-man crew and a maximum speed of 33 miles an hour. Its cargo capacity was only 1,200 pounds, but it could tow 4,200 pounds. The vehicles were to prove useful in October-November 1944 when British and Canadian forces of Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery’s 21st Army Group fought a prolonged, bloody campaign to clear the muddy Scheldt Estuary and make use of the strategic port of Antwerp.

The other breakthrough attributed to Pyke was the formation in the summer of 1942 of the U.S.-Canadian 1st Special Service Force, which distinguished itself in the Italian mountains around Monte Cassino, at Anzio, and in the invasion of southern France. Called the “Devil’s Brigade” by the Germans, it was one of the war’s elite assault units. As Mountbatten told Pyke in October 1943, “You must feel proud to think that the force, the creation of which you originally suggested to me in March 1942, has become such a vital necessity in the coming stage of the war …. One day I feel that you will be able to look with pride on this child of your imagination.”

Pyke continued to churn out logistical ideas from his cluttered desk at Combined Operations headquarters, but many of them were unsuccessful, such as his “uphill rivers” project, whereby cargo would be transported by water through pipelines. In 1943, however, his genius was enlisted to bring to reality the strangest secret project of the war.

After the Royal Navy and the U.S. Navy lost several of their precious aircraft carriers to the enemy in the Mediterranean, Atlantic, and Pacific, Churchill and others sought a stopgap solution while new flattops were still under construction. The inventive prime minister, who had helped to pioneer tank and carrier development in the previous war, suggested the possibility of floating airfields. “If we could create a floating airfield,” he explained, “we could refuel our fighter aircraft within striking distance of the landing points, and thus multiply our air power on the spot at the decisive moment.”

He discussed the idea with Mountbatten, and they came up with a novel notion. Why not use icebergs as carriers? All that was necessary was to cut the top off an iceberg, smooth out a landing deck, and insert engines. Displacing about two million tons, such a vessel should prove unsinkable because, if hit by a bomb or torpedo, the resulting hole would fill with water and quickly refreeze.

Churchill rushed off a memorandum to his War Cabinet. Field Marshal Alanbrooke was not enthusiastic, but the prime minister and Mountbatten were sure they had hit upon something, so they persevered with Project Habakkuk, whimsically named for the Old Testament prophet who had said, “Look over the nations and see, and be utterly amazed. For a work is being done in your days that you would not have believed, were it told.”

Called upon to make Habakkuk a practical reality, Pyke got busy inventing a tough, economical material with which to build the unprecedented “ice boats.” A mixture of wood pulp and 90-percent sea ice called Pykrete (Pyke’s concrete), it was as strong as concrete, could be hewn and hammered like wood, and was amazingly slow to melt in water of any temperature. In order to prove its resiliency, Pyke dropped a chunk into Churchill’s bathtub, and it refused to melt.

The prime minister was sold and encouraged his boffins to proceed. Pyke’s subsequent plan called for the Habakkuk prototype to be 2,000 feet long, 190 feet high, and to displace 1.8 million tons of water—26 times the displacement of the great liner Queen Elizabeth. The 50-foot-thick walls of the cavernous hull would enclose hangars, living quarters, an immense refrigeration plant, and 20 electric motors to power the monstrous vessel. Of Pyke’s building material, Churchill observed, “This substance … seemed to offer great possibilities, not only for our needs in Northwest Europe, but also elsewhere. It was found that as the ice melted, the fibrous content quickly formed a (fuzzy) outer surface which acted as an insulator and greatly retarded the melting process.”

It was agreed that Mountbatten and Pyke’s colleague, Professor Bernal, would unveil Habakkuk at the first strategy conference— code named Quadrant—of the Allied combined chiefs of staff in Quebec on August 13-24, 1943. Churchill hoped that a demonstration of the project’s possibilities would impress Roosevelt and his advisers.

By this time, Pyke was in the doghouse. His stormy time at the War Department, with General McNarney branding him as a “principal handicap,” threatened Anglo-American relations in Mountbatten’s view. “I am afraid Pyke will have to stand down for the good of his own scheme,” he said. Bernal took his place, and Pyke was soon precluded from Combined Operations planning.

At Quebec, the Allied chiefs set May 1, 1944, as the tentative date for Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy, with a senior U.S. officer in command, and agreed to step up operations in the Pacific, invade Italy, send more aid to China, and allow British Maj. Gen. Orde C. Wingate to loose his Chindit long-range penetration columns against the Japanese in Burma.

On August 19, two days into the conference, Mountbatten introduced his unusual project. With the grudging consent of the dour Alanbrooke, he launched into a sales pitch on behalf of the ice-cube carrier and Pykrete. Even Admiral Ernest J. King, the acerbic U.S. chief of naval operations, listened attentively. He distrusted most of his British colleagues, but respected Mountbatten for his courage and intelligence.

Mountbatten arranged a demonstration to prove his point. One of his staffers and Bernal wheeled into the conference room a dumbwaiter bearing two three-foot blocks of ice—one regular ice and the other Pykrete. Lord Louis invited the strongest man present to test the resilience of the new material with an axe, and General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces, was voted. He rolled up his sleeves and splintered the block of ice with one blow. When Arnold swung the axe at the block of Pykrete, it rebounded, jarring his arm, and he cried out in pain. The block was intact.

To further prove his point, Mountbatten drew his Webley service pistol and splintered the block of ice. When he fired at the Pykrete block, it remained solid and the bullet ricocheted, narrowly missing the leg of Air Marshal Sir Charles Portal, able chief of the British Air Staff. “The damn fool!” he snorted. Confusion erupted in the room and outside, where waiting staff officers had heard blows, a cry of pain, and gunshots. “My God,” exclaimed one. “Now they’re shooting at each other!” Afterward, the conference minutes recorded simply, “Professor Bernal demonstrated with the aid of samples of Pykrete the various qualities of this material.”

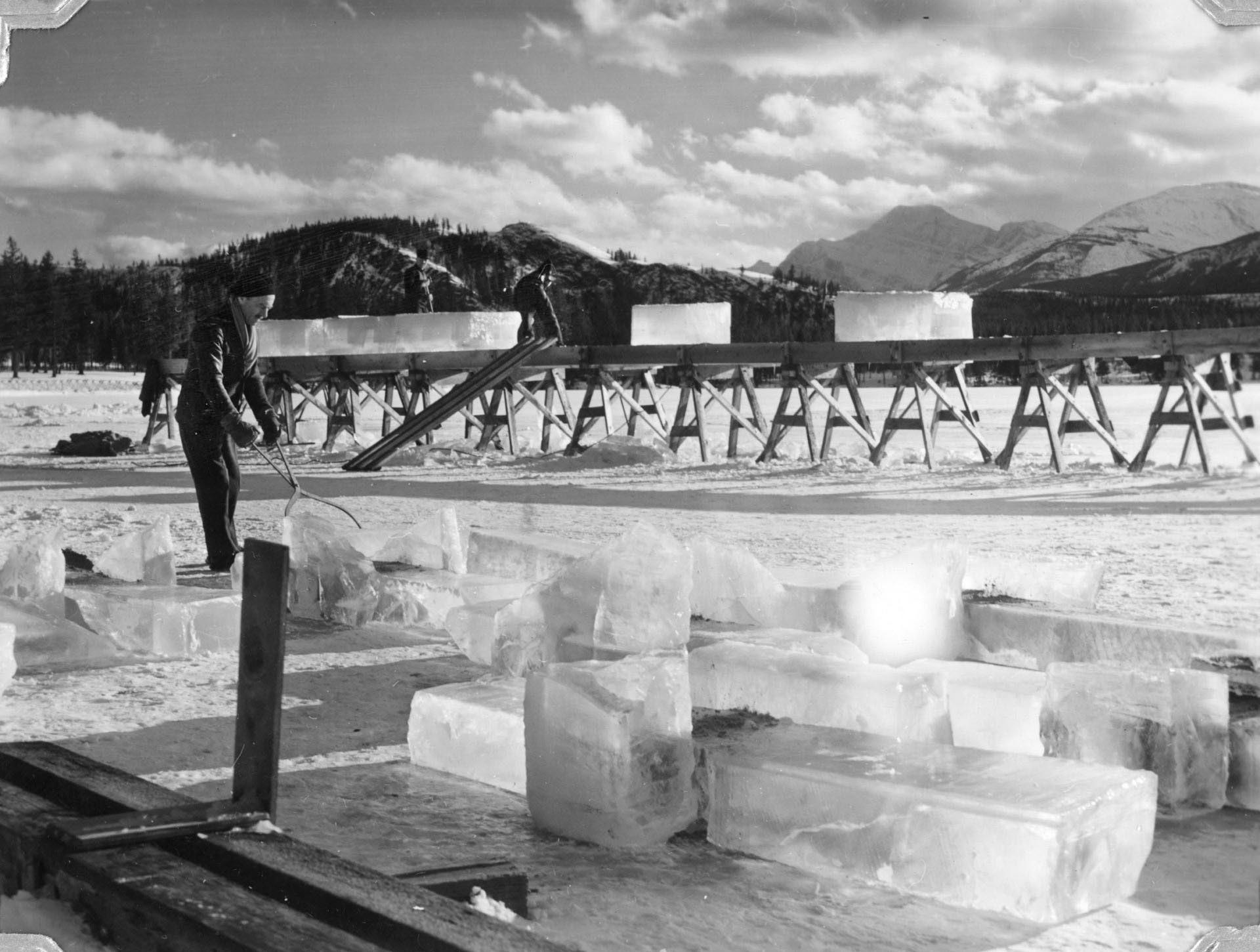

Mountbatten’s demonstration had succeeded in impressing the joint chiefs, so work went ahead secretly on Operation Habakkuk. Canadian workmen built a prototype at remote Lake Patricia in Ontario. Constructed from blocks of mixed ice and wood pulp by 15 men in two months, the vessel was 60 feet long, 30 feet wide, and weighed 1,100 tons. Completed late in 1943, it was roofed over and camouflaged to make it resemble a boathouse.

Despite positive first impressions, however, further research made Habakkuk seem increasingly challenging and expensive. It was estimated that producing and assembling 280,000 Pykrete blocks for one “bergship” would require 8,000 men working for eight months in arctic temperatures, would also need thousands of tons of steel, and would cost about $70 million. “Much development work was done on this side, particularly in Canada,” Churchill eventually reported, “but for various reasons it never had any success.”

The Allied shipyards, meanwhile, were speeding up production and meeting the demands of the Royal Navy and U.S. Navy for more conventional flattops, particularly escort carriers. So, the bold dream of Churchill, Mountbatten, and Pyke melted on the Combined Operations back burner without reaching completion. The ice-cube carrier never went to sea.

After the war, Pyke was a troubled man. He busied himself with attempting to rationalize problems dealing with the basic laws of the universe, feeling that it was his mission to establish a set of radical rules governing certain concepts of time and space, which had eluded even Albert Einstein. But he grew increasingly impatient and exasperated.

At the same time, he could not forget his treatment in America and remained convinced that it was an example of the dedicated thick-headedness of most military planners. Eventually, one day in February 1948, he committed suicide with an overdose of sleeping pills. Learning of his death, a Norwegian officer commented, “It’s the only sensible thing that Pyke ever did.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments