By Robert Ritter von Greim, Leader of Jasta 34b and Jagdgruppe 10

Translated and with comments by O’Brien Browne

This combat diary account by Robert Ritter von Greim describes the frantic attempts of the German Air Force to halt Allied attacks in the closing months of WWI. The first part deals with the massive British assault with tanks, aircraft, and infantry at the Somme on August 8, 1918, a day later remembered as “the black day of the German army” by General Erich von Ludendorff. In the second part, von Greim gives us a vivid depiction of one of history’s earliest encounters between aircraft and tanks.

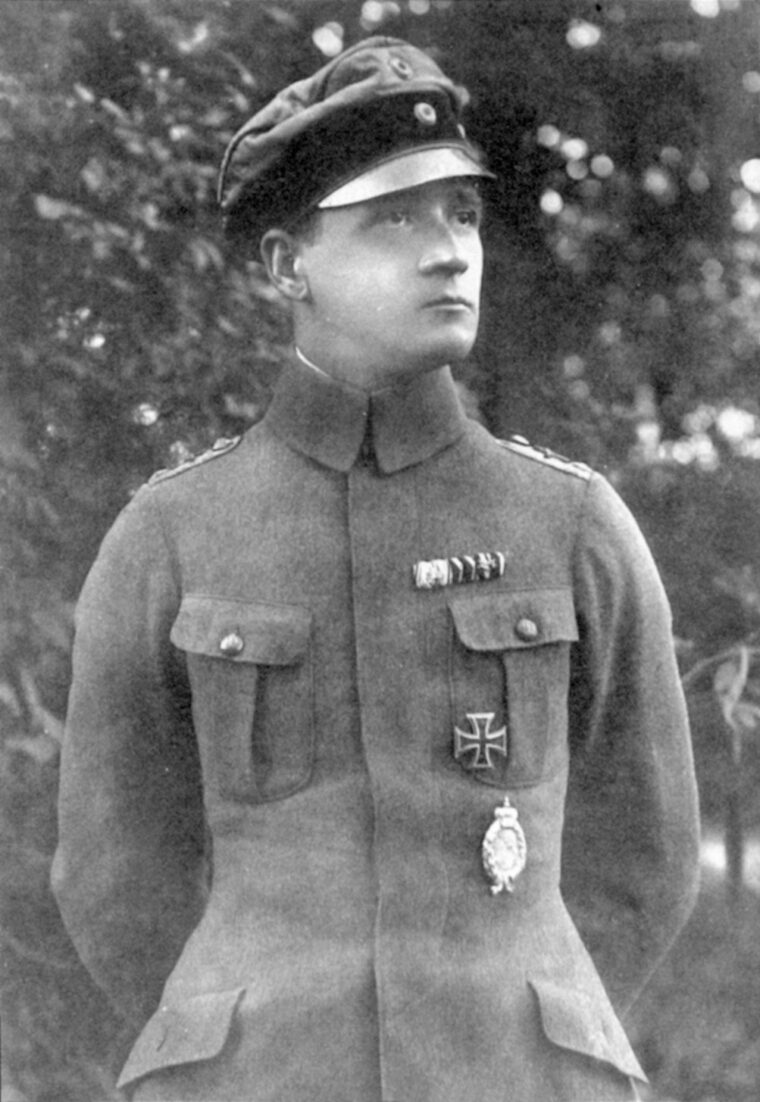

Von Greim, a 25- or 28-victory ace (depending on the source) and winner of the coveted Pour le Mérite award, flew a Fokker D.VII. Commander of Jagdstaffel 34b, and later Jagdgruppe 9 and 10, he survived the war, eventually rising through the ranks of the Luftwaffe until he was promoted to General Feldmarschall by Hitler in the last days of WWII.

In that capacity he served as acting head of the Luftwaffe. Captured by U.S. troops, he committed suicide in May 1945.

August 8, 1918

Another takeoff after an hour had gone by. Visibility and flying conditions had not improved very much, and hectic, dangerous aerial activity was taking place at the lowest heights and in the thick layers of the tenacious, sluggish, rising fog. Here there were neither tactics nor cunning; crossing an Englishman’s path was left to chance. But I did not want to wait long for this chance to come; time was too costly. I therefore decided to get involved in the fight on the ground. Here, too, we could prove ourselves in some adventure.

The battle was raging horribly. Impenetrably thick smoke indicated the center of the furious [British] artillery. The waltz of fire had increased quite a bit in our area; there was hardly any doubt that the opponent had already penetrated to our artillery positions. In a rushing flight, we flew over the thousands of flashing fires from the exploding shells. The English offensive tactics offered a terrible picture to the eye: In the forward lines and at uneven distances were the giant bodies of tanks, as the pioneers and powerful transporters of offensive power for the infantry; behind them shapes jumping forward, lines of trenches, here and there groups falling back and accompanying attacking artillery batteries in open positions.

Thudding hits on my machine suddenly ripped me out of my seconds-long contemplation and required quick maneuvering; I didn’t want to test Fate any further. Cut the petrol, drop down with my guns rattling at those shooting—occupants of craters and everything that the eye could take in in a second. At a very low height I pulled my airplane up in order to repeat the attacks in the opposite direction. Dazzling muzzle flashes reminded me of previously spotted [British] batteries. They were hammering horribly against our positions. An interruption could only help. My plane roared upward again in a sharp bank; I sighted the [British] gun, and its crew, [formerly] posted behind the protective shields, was forced out by my shooting.

My rushing speed did not enable me to get into an immediate, successive fight with a remaining gun; I had to leave this to my pilots following me who, understanding each other, shared the remaining one and shot it up extensively. We could determine with satisfaction that the battery had stopped firing. Tremendous antiaircraft fire forced us to turn back, but friendly waves from out of the shell holes gave satisfying certainty to lasting thoughts of acknowledgment from our infantrymen to our Fokker Staffel [flight].

At the hour of midday, a command came from the Armee-Oberkommando [Army Supreme Command] to defend our rapidly moving aerial formations and to enable our “infantry fliers” [ground-attack aircraft] and artillery spotters to carry out their tasks. Visibility had improved a lot; we hoped that with this third flight our actual tasks could be carried out. At around 500 meters we flew to the front in order to get an overview of aerial activities. [British] ground-attack aircraft and artillery spotters were mostly flying about, under the strong protection of fighter aircraft; now and then one would separate itself in order to dive down at earthly targets. For us, who were heavily disappointed by the morning flights, it was all that we could wish for!

Again, we turned away from the front to come unseen over the clouds and, using surprise, to clean up the whole bunch. At the same time, my sympathetic gaze scanned our old airfield at Foucaucourt, which was already very chopped up. Unseen, we successfully went between mountains of cloud over Villers-Bretonneur, where we once again entered into the open battlefield in the sky. Two observation airplanes flying back from the front were surprised by us and shot down after a short fight. Their protecting aircraft came too late but in their thirst for vengeance gave us a lot to deal with. It was a hot wrestling match for the shooting field, and trails of smoke showed the routes of those shot down in flames damn close by.

As more and more Sopwiths [British single-seat fighters] and Bristol Fighters [British two-seat fighter-bombers] mixed in, our situation—with the addition of being very far into the enemy’s rear areas—became very uncomfortable. By banking and expending great effort, we approached our lines again and two more Bristols fell to the earth in glowing red flames. The attacking spirit of the Englishmen was somewhat spoiled; we arrived safely over our lines.

It was necessary to catch our breaths for a few minutes and to gather the Staffel together. I had hardly finished with this when we were attacked again. This time, though, we were surprised but with the difference that we conquered our surprise, and once again two Englishmen had to pay for this little show with their lives.

But now the petrol gauge indicated it was high time. We turned around and flew home. Cheerfully greeted with well-wishes from the mechanics, the pilots wrote their reports while I, proud of the composure of my Staffel, reported to the Kommandeur der Flieger [CO of Army Aviation] by telephone: “The order to provide defense was carried out to the best of our abilities. Six shot down: two double victories and two single.”

The Staffel was put on barrage patrol at 4 o’clock. Until then, I granted takeoffs at will against the English bombers, which were still approaching at an impudent height. Along with full acknowledgment [in the Army Supreme Command dispatches] for me and the entire Staffel, I also received the comforting news that numerous Jagdstaffeln [combat squadrons] from neighboring armies, indeed even from Flanders, were approaching here, and that the organization of their deployment (with the exception of the Staffeln of the “Richthofen” Geschwader [squadron], which could take off at will) in the entire army sector would be taken over by me. [Still,] with my group, consisting of three Jagdstaffeln, and a neighboring Staffel whose fighting strength had significantly suffered because of losses during the recent flights, we alone could hardly stand our ground for much longer against the incredible enemy superiority along the entire army’s length.

The next hours went by in great haste. Reports came and went, the deployment of the Staffeln under my command had to be organized, petrol and munitions made ready for them—steps which were very difficult to organize because of the continual disruption of the telephone lines.

But the Staffel was immediately made ready for takeoff so that, even if we were still greatly inferior, we could at least continue to take on the opponent. The inferiority of our numbers was more or less balanced out by the reckless performance of each single individual. Thus fell the Pour le Mérite-winning pilot Leutnant Loewenhardt [a 54-victory ace and leader of Jasta 10] from the “Richthofen” Geschwader (which had arrived with two Staffeln), in a wild battle against superior numbers, and still more dear comrades followed him into the realm of shadows on this day [August 10, 1918].

At 4 o’clock we took off for the fourth time. The English squadrons could hardly be outdone anymore. Everywhere Staffeln scraped; the tracers’ smoke trails lay like spider webs across the sky.

In the evening hours we took off for a fifth time. White signal flares indicated the forward lines which we, to our chagrin, unfortunately discovered very much to the west of Foucaucourt. Like a meteor, a glowing red fireball—a Sopwith—crashed to the ground after a tough aerial engagement—it was the fourth victory of my master shooter of the morning and the eighth victory of my Staffel on the first day of this incredible defensive battle. We got out of our machines dead tired. We had been in the air for 10 hours; for 10 hours we had fought under the most difficult conditions. Thank God that He let night come.

And once again the death messengers of the night [i.e., British bombers] droned and hummed , directional signals hissed, cannon sparkled, and the antiaircraft guns barked.

August 23, 1918—Tank Attack

Regarding enemy aerial activities, the following days were, on average, like August 8. On the ground the fighting had died down; however, new attacks were expected, and to maintain the fighting strength of my Jagdgruppe [combat group], it was necessary to transfer the airfield still farther away, toward Hervilly. Success followed success in tough battles.

On the evening of August 22, the drum-fire began anew, increasing in the morning hours to a terrible force. Because of a telephone message that enemy ground attack aircraft were at work, we took off at dawn. The haze, which on August 8 Nature had laid before the eyes of our artillery and infantry, and helped the opponent’s tank attack so much, was artificial this time, made by smoke bombs. Thick clouds waltzed over the torn crater fields, mixing themselves with the dark smoke clouds of the exploding shells and were suddenly twisted again by powerful fountains of earth from new impacts. Right below us lay our old airfield, disheveled to nonrecognition by heavy fire; here, recognizable by magnesium fire and signal flares, was our forward line. There was nothing to be seen of the enemy whom we were searching for. We flew to the Somme, we flew to the south, angrily greeted by many machine guns and antiaircraft guns, but there wasn’t an opponent anywhere.

I was scanning for worthwhile targets, accompanied by my true, inseparable comrade-in-arms Pütz [Johann Pütz, a 7-victory ace], when from the smoke and thick dust a strange creature pushed outward, unhindered by the shells exploding to the right and left, crushing everything which stood in its way: a tank. Suddenly a second one followed. My thoughts came as quick as lightning: how to attack it? From the front, from the back, from the side? Where are the strong and the weak parts of the armor? Isn’t all effort useless? Until now none of these monsters had been bagged. I still have a lot of bullets in my belt, incendiary and armor piercing. Let’s risk it!

For the first attack I chose the broadside. Pütz saw my intentions and got to work on the second tank. At first only with armor-piercing bullets firing from one weapon, we rushed down at both giant worms. Only at close range did I let both weapons play. Missed! The undamaged fellows continued undisturbed along their way. But this fight is much more real for us: devastating machine-gun fire was the answer from the tanks, reason enough for me to yank my single-seater upward, with fluttering wings, in a sharp bank. This style of fighting was not leading to success. With astounding speed, the monsters waltzed forward.

What if I hit the tank vertically from above, I think? Quickly, we again climbed up to five hundred meters. Well, then, once more to it! Gas off—the machine stood on its nose—and in a vertical dive with both guns firing, I dove downward. Right over the tank, I pulled my machine out; although the struts and spars groaned, they held. And look there—this time I have received no machine-gun fire. Or couldn’t I hear it in the roaring flight? No indeed—the tank stands still. The second one, which Pütz went after at the same moment, also lay motionless. Mistrustfully, we observed the two for a long time. But not the slightest movement betrays any life. We flew away contentedly. Hardly had we landed when a report from the forward lines came in confirming our success: both tanks were and remained done for!

O’Brien Browne is a freelance writer living in Heidelberg, Germany, who writes on historical and cultural matters. He is a frequent contributor to Military Heritage.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments