By John W. Osborn, Jr.

“No other two races have left such a mark on the world” as the Jews and the Greeks, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill once wrote.

“Both have shown a capacity for survival, in spite of unending perils and sufferings from external oppressors, matched by their own ceaseless feuds, quarrels, and convulsions,” Churchill observed. “The passage of several thousand years sees no change in their characteristics and no diminution of their trials and their vitality.

“They have survived in spite of all the world could do against them, and all they could do against themselves, and each of them from angles so different has left us the inheritance of its genius and wisdom.

“No two cities have counted more with mankind than Athens and Jerusalem.

“Their messages in religion, philosophy, and art have been the guiding lights of modern faith and culture. Centuries of foreign rule and indescribable, endless, oppression leave them still living, active, communities and forces in the modern world.

“Personally I have always been on the side of both, and believed in their invincible power to survive internal strife and the world tides threatening their extinction.”

Churchill’s commitment to the Greek people was to be fully revealed in the dark December days of 1944 in Athens as the furnace of World War II was beginning to cool into the colder global conflict to come.

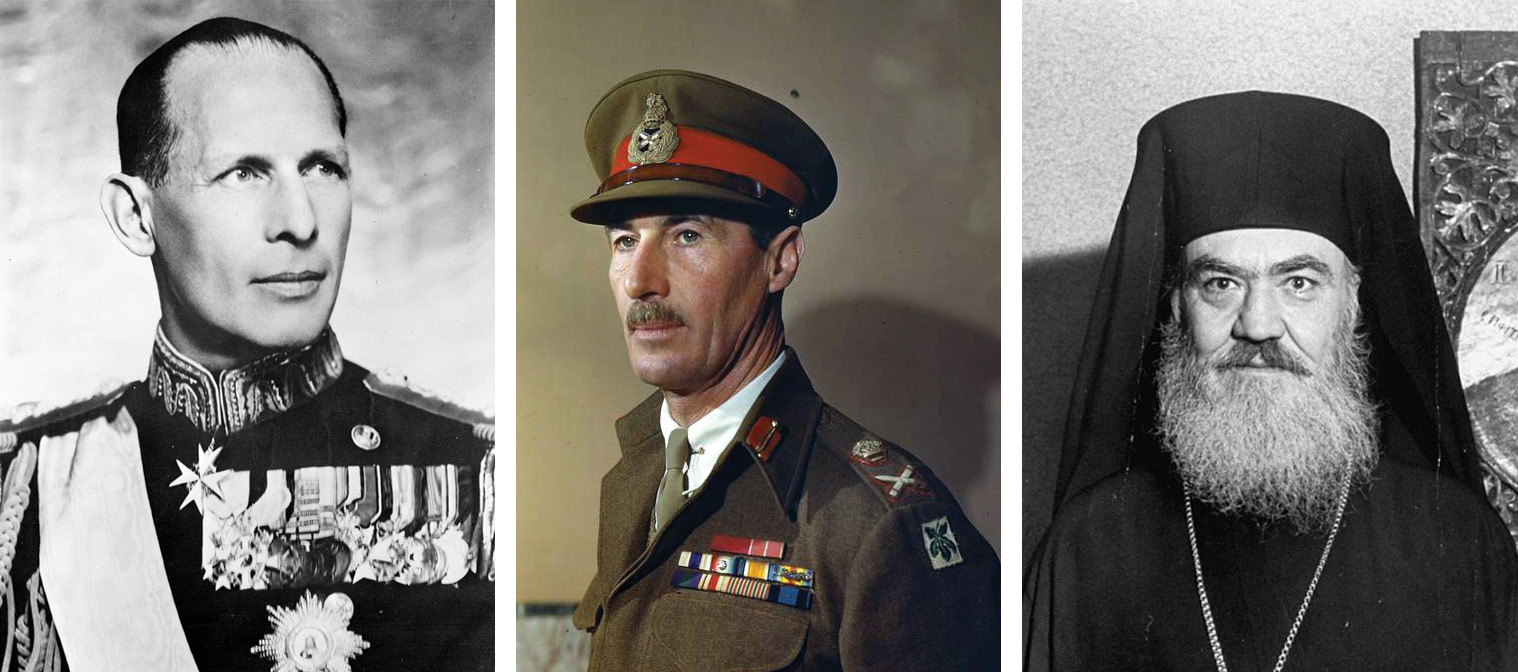

Greece’s slow descent to its December of despair began in 1935, when the Greek military overthrew the country’s first republic since ancient times after a mere 12-year existence, then recalled from exile probably the most hopeless mismatching of king with country. “It would be hard to find two worse advertisements for hereditary monarchy than George of Greece and Peter of Yugoslavia,” Churchill’s wartime Private Secretary John Colville would wearily say.

In the cradle of democracy a year later, King George II dissolved the Greek parliament and became a puppet behind a Fascist-style dictatorship with a secret police modeled after the Gestapo. However, personality alienated the king from those supposed to be his people just as surely as politics did. Greeks are among the most individualistic, idiosyncratic nationalities on Earth, and King George was of completely foreign heritage, of all things Danish. After over a decade in exile, he struggled to speak what was supposed to be his native tongue. He seemed just as foreign in his manners, completely isolated and indifferent behind the country’s military masters.

The descent to December accelerated when, in October 1940, for no more apparent reason than just to prove to Hitler he could have his own wartime walkover, Italian Dictator Benito Mussolini sent his armed forces on an ill-advised invasion of Greece. But the Greeks shocked Mussolini and the world, inflicting embarrassing defeats on the invaders. Hitler intervened to save his Axis partner from further embarrassment. However, the British, in Churchill’s own ill-conceived action, sent troops to aid the Greeks.

Greek units would fight alongside the British in the Middle East, but George II proved as sorry a symbol in exile for the second time as he had been during his earlier banishment in the 1920s. While in Egypt, he once greeted a visiting delegation of resistance leaders in white tennis togs, racket in hand, straight from the court.

While Greeks were enduring one of the war’s most obscure but horrific occupations, British missions of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) parachuted into Greece to work with the Resistance, including paralyzing the railroad network that helped to deliver supplies to General Erwin Rommel in North Africa for six weeks. But the British would find a different sort of conflict, particularly as it became clear in Greece that there was more than one “Resistance.”

“Political quarrels hampered guerrilla warfare, and we soon found ourselves in a complicated and disagreeable situation,” Churchill was, with understatement, to write. In customary Greek quarrelsomeness, there were two main Resistance groups, the National Democratic Army (E.D.E.S. in its incomprehensible Greek initials), for restoring the Republic, and the E.A.M. (National Liberation Front), a more broad-based coalition with its military arm, the E.L.A.S. (Peoples’ Liberation Army).

While relations with E.D.E.S. were cordial and cooperative, the British found E.A.M-E.L.A.S. different, and ominously so. A British officer working with its military leader would say, “I had no doubt that after one of our all-day drinking sessions in the most friendly atmosphere, he would have literally flayed me alive if it suited his purpose.”

An E.A.M. leader once curiously commented, “We have all been outlaws for years.” The pronouncement raised suspicions, and the skill which E.A.M. demonstrated in safely bringing a British officer into and out of Athens showed that the organization was very practiced in clandestine conduct.

Investigation by the British finally found the truth behind the facade of the E.A.M.-E.L.A.S. coalition. It was secretly controlled by the Greek Communist Party, banned and driven underground by the prewar regime. Although the British were willing to work with Tito’s Partisans in Yugoslavia, the potential threat of a post-war Communist Greece to British interests in the Mediterranean, especially the Suez Canal, put the Greek situation in a decidedly different category.

Added to the mixture of E.D.E.S. and E.A.M. was the Greek government-in-exile, holdovers and royalists, all claiming stakes in the future of post-war Greece. “All had thought that the Allies would probably win the war, and the struggle among them for political power began in earnest to the advantage of the common foe,” Churchill would complain. The first signs that a troubling winter of 1944 was brewing in Athens emerged in October 1943, open warfare broke out between E.D.E.S. and E.L.A.S., each blaming the other. Then, in April 1944, mutinies in support of E.A.M. erupted in units of the exiled Greek army and navy in Egypt.

SOE officers in Greece brokered a truce while British troops and loyal Greek sailors suppressed the mutinies, with 50 Greek casualties and a British officer, Major R.J. Copeland, killed. A new Greek government was formed with a longtime opponent of the King, Georges Papandreou, as prime minister. Major Copeland, Churchill would say, “certainly did not die in vain,” but he would not be the last British soldier to lose his life in the impending war for control of Greece.

As World War II ebbed, E.L.A.S. grew to almost 50,000, E.D.E.S. little more than 10,000. In September 1944, the Germans finally began evacuating Greece. E.L.A.S. fought alongside E.D.E.S., harassing the Nazis on their way out, and E.A.M. joined Papendreou’s government. Churchill, however, was not convinced. “Obviously,” he warned, “they are seeking nothing but the Communization of Greece, without allowing the people to decide in any manner understood by democracy.”

The first contentious decision would concern the fate of King George II.

The one issue E.A.M., E.D.E.S., and Papendreou agreed on was a plebiscite on the return to the throne. The King, not surprisingly, resisted. “We had no intention of interfering with the solemn right of the Greek people to choose between a monarchy and a republic,” Churchill wrote, but he unaccountably balked at the consensus candidates of the Greeks, Foreign Secretary Sir Anthony Eden, Ambassador Reginald Leepers, and Churchill’s special envoy to the Mediterranean Harold Macmillan for Regent, the Orthodox Archbishop of Athens, Damaskinos.

“W. has the knife into the Archbishop and is convinced that he is both a quisling and a communist,” Eden remarked. In fact, the archbishop was a hero to all Greeks for his staunch stand against the Germans, holding public prayers at sites of massacres, hiding 10,000 Jews in monasteries, and forcing an end to deportations for slave labor in Germany with his protests.

Once the Germans were out, the British moved in 4,000 mostly administrative and technical personnel under Lieutenant General Ronald Scobie, entering Athens on October 2, 1944. The Papendreou government arrived three days later. King George departed for London, and E.L.A.S. ordered its units in Athens to place themselves under British command. Nevertheless, Churchill wrote Eden, “I fully expect a clash with E.A.M., and we must not shrink from it,” but the clash would come more quickly and calamitously than the prime minister even expected.

Tensions in Athens rose swiftly as an extremist secret right-wing group assassinated E.A.M. members and supporters while the British kept on the hated police of the collaborationist regime to preserve order, formed security battalions of other collaborationists, and moved in Greek troops and two brigades of the 4th Indian Division from the front in Italy. Finally, on November 26, Scobie ordered E.L.A.S. to disarm itself and demobilize.

It refused unless the police, security battalions, and Greek troops did so as well. On December 2, E.A.M. quit the government and called a general strike, which shut down city services and commercial life. The next day thousands of members and supporters took to the streets to protest.

A mob attempted to storm Papendreou’s apartment but was beaten back by police while he cringed inside; another confrontation would be more disastrous and deadly.

A mass gathering faced police in Constitution Square in Athens as shots rang out from an unknown source. Panicking police fired, killing 28 demonstrators and wounding scores more. Crowds swelled to 60,000 as agitators dipped rags in the dead demonstrators’ blood, waving them like banners to incite the angry Athenians. Scobie immediately ordered E.L.A.S. to evacuate the city, but instead by nightfall the city was in all-out rebellion.

By the following day E.L.A.S. had rushed in reinforcements estimated at 20,000, and soon after they had taken all but three of the police stations, those inside shot, hung from lampposts or telephone poles, even dismembered alive with meat cleavers. E.L.A.S. fighters cut the road between Athens and its harbor at Piraeus. “The mob violence by which the Communists sought to conquer the city and present themselves to the world as the Government demanded by the Greek people could only be met by firearms,” Churchill reflected. “There was no time for the cabinet to be called,” and on his own the prime minister issued his most incendiary instruction of the war.

Churchill and Eden were working until 2 am on December 5. Finally, Churchill let Eden go to bed. An hour later he started working on his scorcher to Scobie: “You are responsible for maintaining order in Athens and for neutralizing or destroying all E.A.M E.L.A.S. bands approaching the city … Do not hesitate to fire on any Greek armed male in Athens who assails the British authority or Greek authority with which we are working … Do not hesitate to act as if you were [in] a conquered city where a local rebellion is in progress … We have to hold and dominate Athens. It would be a great thing for you to succeed in this without bloodshed if possible, but also with bloodshed if necessary.”

John Colville sent it out at 4:50 am; Churchill would later offer the jaw-dropping explanation for the message that it was inspired from his dealings with the Irish!

The British in Athens were soon in combat with a resistance movement, E.L.A.S., armed with stockpiles of weapons and ammunition deliberately left behind by the Germans. The E.L.A.S. fighters sniped from rooftops and tossed down homemade fragmentation bombs made from pairs of dynamite sticks in a tin can packed with scrap metal. They contemptuously called the makeshift bombs “Scobie Preserves.” They ambushed from alleyways, sent tramcars packed with explosives crashing into British positions, and would attempt to thunderously take the struggle below the streets.

Some 80 percent of the E.L.A.S. fighters were in plain clothes, and the British soon had to extend Churchill’s order “to fire at any armed Greek male” to females as well, many of them girls the British had fraternized with during the weeks before.

“Corpses lay on top of the other like carcasses in an abattoir, ” a British officer would remember, “awaiting a lull in the surrounding battle so that they could be quickly buried in parks and fields. Fire engines tore through the streets and the sky was crimson from the reflections from burning buildings.”

Caught in the chaos was the civilian population, after the German occupation which had ended with 30,000 dying of starvation. “Everywhere there was fear and suffering,” the British officer recalled. “There was not only no food, no water, no light and no warmth, there was no safety or security anywhere.”

Nor was there for the British, as a typical day’s report from Scobie to Churchill related: “Increased activities on the part of the rebels and widespread sniping limited progress during the day … By mid-day the total of rebel prisoners under military guards was 35 officers, 524 other ranks. These figures did not include those held by the police, as it is difficult to obtain accurate figures from them. Some progress was made by the 23rd Brigade in house-to-house clearing throughout the afternoon. A further section in the center of the city was cleared by the Parachute Brigade. Marine reinforcements had to be landed from H.M.S. Orion to deal with serious sniping of Navy House, Piraeus, by rebels who infiltrated into the area south of Port Leontos. In the face of strong opposition our troops were forced to withdraw in one area.”

The fighting sparked outrage in Britain and the United States, where it was seen as the British for old imperial purposes crushing democratic resistance to an unpopular King. Churchill quickly crushed criticism in Parliament with his angriest address of the war saying, “Democracy is no harlot to be picked up in the street by a man with a tommy gun. He demanded and overwhelming won a vote of confidence, 279 to 30.

On December 11, Field Marshal Sir Harold Alexander, Allied Commander-in-Chief for the Mediterranean, flew into Athens to see how serious situation was and found out literally on the spot.

“Not a happy welcome!” he would relate. “When I asked for a motor car I was told I would need an armored car … In due time two armored cars arrived to take us the six or seven miles to Athens. We bought a lot of bullets on the journey—we could hear them hitting the outside of our armored car—but we were not stopped.”

At Scobie’s headquarters Alexander learned and reported to Churchill’s dismay, “British forces are in fact beleaguered in the heart of the city.” They were hemmed into a zone only two miles long and a few blocks wide. There was only ammunition left for three days, food for six. Alexander diverted two brigades and a tank regiment headed for Italy to Athens and transferred a quartet of RAF squadrons from the Italian front. Soon, Spitfires were strafing and rocketing while tanks rumbled and roared to add to the cacophony of chaos into which Athens had descended.

“Is there now any danger of a mass surrender of British troops?” Churchill was soon nervously asking of Alexander. The British managed to reopen the road to Piraeus though the supply convoys into the city had to run a gauntlet of fire. The British gave their own moniker to the mayhem, though it was longer, the Mad Mile, but an air base was captured by E.L.A.S. with 250 RAF personnel taken prisoner. Greek troops were cut off in the suburbs, and in the mountains to the northwest, E.L.A.S. had driven E.D.E.S. out, 7,000 members and supporters evacuated by the Royal Navy in a miniature Mediterranean Dunkirk.

“It will be possible to clear the Athens-Piraeus area,” Alexander reported, and on December 20 the British launched an all-out counterattack to accomplish just that, creating a Hellenic Stalingrad. As it was raging on, Churchill was spending a rare quiet Christmas Eve with his family at Chequers, the official Prime Minister’s country residence. He came to a sudden decision, phoning his physician, Lord Charles Moran, to inform him of it.

“I’m off to G.” Moran recorded the conversation in his diary.

“When?”

“Oh, tonight.”

Moran, whose responsibility it was to accompany the septuagenarian statesman on his wartime travels immediately rushed for Chequers, wondering on the way why they were headed to Gibraltar.

He found out on arriving, “G. is Greece.”

“I felt sure I ought to fly to Athens,” Churchill explained of his dramatic decision later, “to see the situation on the spot, and especially make the acquaintance of the Archbishop, around whom so much was turning.”

Colville recalled, “A chaotic evening ensued.” He made arrangements, informed King George VI, the Cabinet, and the Chiefs of Staff. Shortly after midnight he, Churchill, Eden, Moran, Churchill’s naval aide, and a pair of pretty secretaries were taking off for Athens. They landed outside the city at a heavily guarded base at noon to be met by Macmillan and Leepers. Aboard the aircraft they all talked for hours, finally deciding to convene a conference of all the Greek parties including E.L.A.S. for the following day, to be presided over by Archbishop Damaskinos.

In armored cars the group rode down to Piraeus to board the cruiser HMS Ajax and wait to finally meet Damaskinos. When the captain warned that he might have to fire in support of troops in the city, Churchill responded, “Pray, Captain, I come here as a cooing dove of peace, bearing a sprig of mistletoe in my beak—but far be it for me to stand in the way of military necessity.”

The crew was making Christmas merry in their own way with a costume party when the Archbishop, over six feet tall, his hat making him look seven, great beard, and still the physique of the champion wrestler of his youth, arrived. The crew, unaware of what was going on or who he was, took him for a Greek Santa Claus and proceeded to cheerily clap and dance around him.

“The Archbishop thought this motley gang was a premeditated insult, and might have departed for shore but for the timely arrival of the captain who, after some embarrassment, explained matters satisfactorily,” Churchill recalled. “Meanwhile I waited, wondering what had happened. But all ended happily.”

Not entirely for John Colville. The Archbishop brought his own Christmas cheer, a potent Greek brew Colville struggled to get down without choking. Churchill had evidently been finally filled in on the Archbishop’s record and his forthright condemnation of E.L.A.S. He won Churchill over immediately. “We are now in the topsy-turvy position of the Prime Minister feeling strongly pro Damaskinos,” a recovered Colville said.

Preparing to leave in the next afternoon for Athens, Churchill, renowned for writing “action this day” on his memorandums, was prepared to be really ready for this one with more than just paper, carrying a pistol as he was preparing to board an armored car and asking Colville if he was armed. He said he wasn’t but then came back with the driver’s tommy gun.

“What is he going to do?” Churchill asked.

“He will be busy driving,” Colville replied.

“But there will be no trouble unless we are stopped, and what is he going to do?” the prime minister asked.

“Jock had no reply,” Churchill wrote. “A black mark! We rumbled along the road to the Embassy without trouble.” There they picked up Alexander, Leepers, and Damaskinos, then drove on to the 6 pm conference at the old Greek Foreign Ministry, where the setting at the conference table was as bleak as the situation, lit lamps, blankets all around for lack of electricity and heating.

“From outside came the muffled din of battle as we waited for E.L.A.S. to appear,” Leepers wrote. No truce had been declared, and the fighting continued.

After a half-hour, a trio of delegates, “shabby desperados” to Colville, but to Churchill “presentable figures in British battle dress” arrived claiming they had been held up at checkpoints. It came out later that E.L.A.S. had been planting a ton of explosives in the sewers beneath British headquarters at the Hotel Grand-Bretagne thinking the conference would be held there and had canceled the blast at just the last moment. Churchill spoke briefly, “We have begun the work, see that you finish it!” and abruptly exited.

The following morning back on Ajax Churchill stunned everyone, announcing he wanted to go back into Athens to observe the fighting. “I would like to go to some forward observation post and see the problem for myself. It helps me to see things.”

In his early days of his political career, Churchill had been ridiculed for going, in top hot and Saville row best, to view a gun battle between policemen and anarchists. Just the previous June, King George had tactfully talked him out of closely observing the D-Day operations. Now, Alexander simply laid down the law.

With that, Alexander said to Moran, “Have you been to the Acropolis, Charles? You haven’t? Oh, we must remedy that.”

Moran and Alexander set off in just a touring car with only a pair of parachute officers for guards.

They found British soldiers stationed at the Acropolis. “It’s a lovely spot, sir,” one told Alexander. “We have got all of Athens in our line of fire.”

Alexander suggested walking back down. Along the way he spotted another temple. “I don’t think you ought to go there,” he was warned. “A man was killed there this morning. There are some snipers over there.”

A legend in the British Army for his courage, Alexander dismissed the danger, “Oh, nonsense. If we go that way it’s quite safe.”

“Our guard made one more attempt a little further on to dissuade Alex, but to no purpose,” Moran wrote in his diary. “We loitered in the temple for some time.” Moran didn’t say whether he had enjoyed this little Athens adventure.

The Greeks in the meantime had been conferring in their usual way: “bitter and animated” according to Churchill. A government minister and E.L.A.S. representative traded choice Greek curses, in the end held back from coming to blows. They grew up in the same village. But, finally, at 5:30 that evening Damaskinos reported to Churchill the parties had agreed to a plebiscite on King George II with himself as regent and a new government, but he would refuse to readmit E.A.M.

“It scotched the legend that the British were trying to force the King on the people,” Leepers would conclude. “For that reason Mr. Churchill’s visit to Athens was abundantly justified.”

Back in London Churchill kept King George II up until 4:30 am, when he capitulated. In the meantime, the British and Greek forces had captured the E.L.A.S. headquarters in Athens on December 29, and their last stronghold, Mount Parnassus, on New Year’s Eve. Damaskinos and a new prime Minister took office on January 3, 1945, and a cease-fire with E.L.A.S. was signed 12 days later.

“Thus ended,” Churchill wrote, “the six weeks’ struggle for Athens, and, as it ultimately proved, for the freedom of Greece from Communist subjugation.” The United States had been notably neutral, but Josef Stalin’s silence had been more interesting, as Soviet interests might be well served with Greece under communist rule.

Stalin had conceded to Churchill that Greece was within the British sphere of influence. A Soviet military mission to E.L.A.S. six months earlier had reported unfavorably on its prospects for success. Besides, the Communist Party in Greece had never been under Stalin’s direct control. The revolt had been sudden and launched without his approval. He apparently saw no value in providing tangible support.

In what became known as the Dekemvriana (December Events), British losses were 237 killed and 1,800 wounded. The Greeks never officially announced a death toll, but estimates run 1,200 Greek Army personnel killed, 2,000 E.L.A.S. dead, and 3,000 lost.

An E.L.A.S. leader proclaimed the communists lost “Because we did not kill enough people. Revolutions succeed when rivers redden with blood.” E.L.A.S. grimly made sure the mountains did, slaughtering villagers along the fighters’ route of retreat, forcing others at gunpoint out among the peaks to starve or freeze, and up to 15,000 more died.

Civil war would break out a year later, ending in 1949 with the final defeat of E.L.A.S. and another 100,000 deaths. However, in it the seeds of yet another Greek tragedy were being planted. In order to defeat the Communists, Fascist-leaning officers of the pre-war dictatorship and even the collaborationist regime were allowed into the Army. Two decades later these men would return Greece to military misrule.

When the plebiscite was held in 1946, King George II was returned to the throne, but without enthusiasm. Greeks evidently saw him as the price for continued British support. He died, widely unmourned, only a year later. His successors would prove just as incapable of kingship, and the Greek monarchy would end again, for good, with his nephew fleeing after the notorious Colonels’ Coup of 1967.

In 1951, Churchill concluded, “I would consider that, taken by and large, my policy was vindicated by events; and that is true not only of the period of the war, but up to the present time of writing.”

Though the revolt had been unsanctioned and then unsupported by Stalin, the battle for Athens in December 1944 came to be seen as the first battle of the undeclared Cold War.

In 1947, London informed Washington that it could no longer afford to support Greece in its civil war, and President Harry S. Truman appeared before Congress to enunciate the doctrine that came to bear his name, committing the United States to support countries opposing Communist aggression and subversion. The long road soon led to Korea and later to Vietnam.

Author John W. Osborn, Jr., is resident of Laguna Niguel, California. He has written for WWII History on a variety of topics.