By Fred Eugene Ray

The wars fought by Sparta and Athens in the fifth century bc pitted one city-state with ancient Greece’s greatest army against one boasting her most powerful fleet. Yet the Spartan and Athenian soldier followed ways of war that differed in far more than a simple preference for fighting on land rather than sea. In fact, the distinctive approaches that a Spartan hoplite and Athenian soldier took to combat embraced a wide range of tactics, only a few of which were tied to their traditional divide at the shoreline.

Military historians have tended to focus on the severe boyhood training regimen in Sparta (the agoge) and the potent combination of hardy physique and iron-willed martial philosophy it promoted. But the Spartan way of war was not simply a matter of outstanding individual toughness, strength, or even weaponry skills. Superior tactics played key roles as well—discretion was often the better part of valor for Spartans. They were adept at assessing battle odds and, should these not be to their liking, heading home without a fight.

Despite its fierce image, Sparta had a more extensive record of dodging armed confrontations than any other Greek city-state. It was not unusual for Spartan commanders to turn back before crossing a hostile border if the omens were bad. And even on the brink of combat, they might still choose to avoid action. Spartan King Agis II (427-400 bc) once claimed that “Spartans do not ask how many the enemy are, only where they are,” but on at least four occasions he personally refused engagement with the enemy.

Advantages in the Spartan Hoplite Approach to Warfare

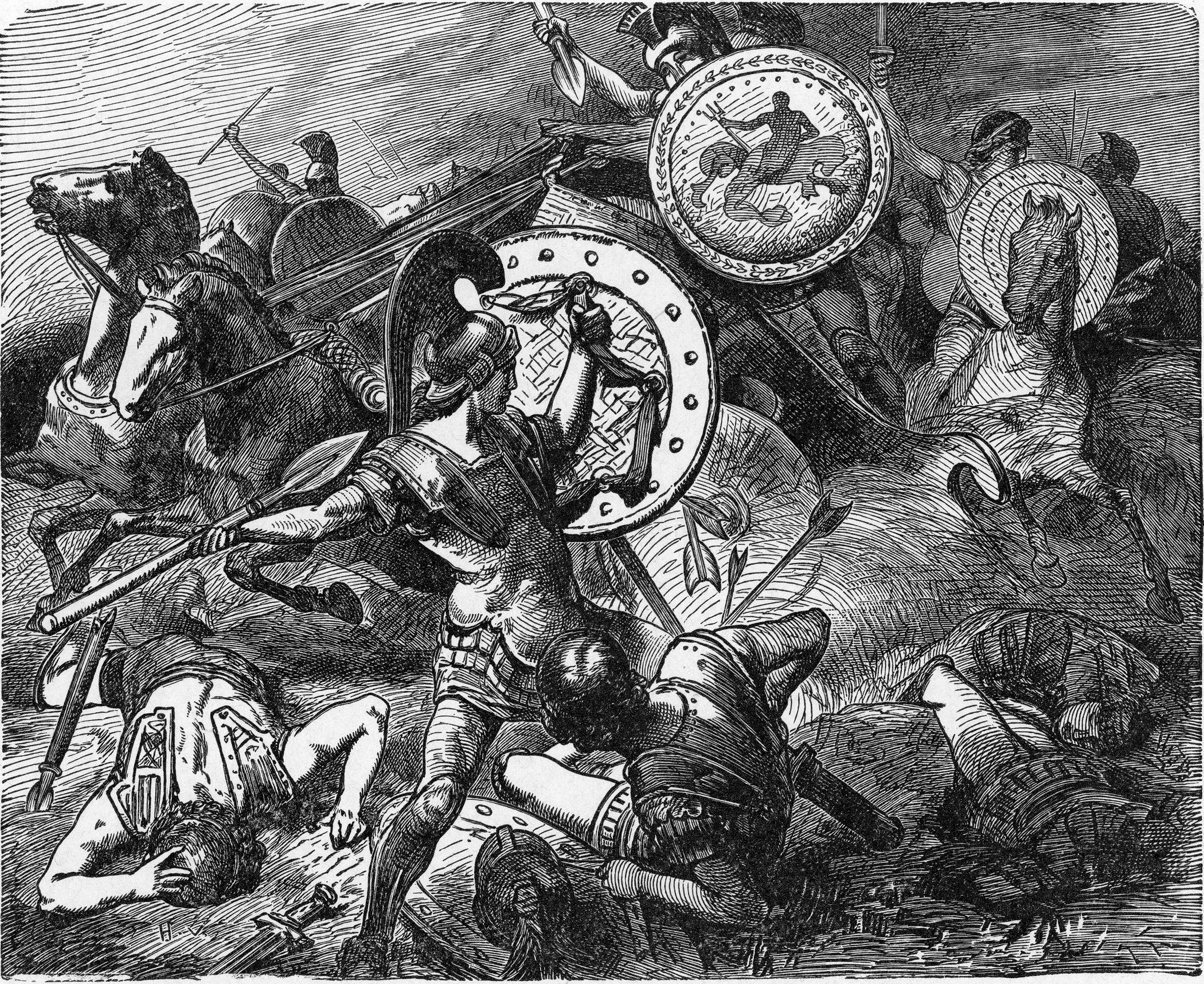

Classical Greeks fought in a dense linear formation or phalanx as armored spearmen known as hoplites. These hoplites were protected from their ankles up by greaves, cuirass, shield, and helmet as they stood close alongside each other in ranks that could be many hundreds of men wide. This allowed them to present a broad front that was hard to overlap or outflank. But there was a limit to how thin a formation could be without falling into disorder. Thus, most Greeks tried to form a file at least eight men deep to accept battle. Spartans, however, could advance and maneuver effectively in files as slim as four men. Those in the first three ranks struck overhand with their spears at the enemy front, and the fourth rank joined rows two and three in pressing shields into the backs of their fellows in a concerted effort to shove through the opposition, a tactic called othismos. This ability to maneuver when short-handed yielded success several times, most famously against a much larger Arcadian army at Dipaea in 464 bc.

Most Greek armies advanced with men shouting encouragement and issuing distinctive battle cries. They would then rush the last few yards into close action. In contrast, Spartans moved forward slowly in measured steps to the sound of pipes and the rhythmic chanting of battle poetry. This allowed them to keep excellent order all the way into engagement. Moreover, the Spartans saw their opponents’ noisy rush as amateurish, signaling false bravado to suppress fear. Their own deliberate and disciplined pace was meant to set a tone of both overwhelming confidence and deadly menace. So unnerving was this approach that many foes broke and ran before first contact.

Spartan hoplites followed a natural urge when marching into battle to edge closer to the man on their right. They did this to gain better cover from the shield held on his left arm. This tendency caused phalanxes to fade toward the right as they advanced and often resulted in a mutual overlap of formation flanks on opposite ends of the field. The Spartans exploited this by deliberately exaggerating their own rightward movements. They would combine the movement with well-practiced wheeling by elite troops on their far right to curl around a foe’s left flank. Once enveloped, the encircled wing would break and run, causing the enemy phalanx to collapse.

Besides exploiting the common phenomenon of rightward drift, Spartans also used more unique schemes on the battlefield. King Agis once shifted units in his formation during an advance. To attempt this in the very face of the enemy suggests that Spartans considered such risky moves to be well within their capabilities. Athenian general Cleandridas defeated Italian tribesmen in 433 bc by hiding a contingent of hoplites behind his phalanx. This disguised his true strength and, once engaged, let him wheel his men against the enemy flank to trigger a rout.

The most daring Spartan battle maneuver was to break off in the midst of combat and withdraw. All other Greek armies shunned this for fear of inviting disaster. The Spartans, however, could not only pull out of hopeless spots at minimal loss, but could also fake the maneuver and trick foes into breaking formation to give chase. Herodotus cited such false retreats at Thermopylae in 480 bc. The Spartans then wheeled about each time and obliterated the overly eager Persians, who had fallen into premature and disordered pursuits. Plato claimed the Persians also suffered this same Spartan ploy at Plataea one year later.

While Spartans heavily punished those breaking ranks to follow their feigned retreats, they themselves refrained from any sort of pursuit. First, they saw no profit in risking precious lives to chase an already defeated enemy. Furthermore, staying on the battleground allowed them to possess the field at day’s end. This was the universally accepted definition of formal victory in Greek warfare. Finally, by maintaining formation, the Spartans could rapidly reform on a different front, giving them the opportunity of mounting a second attack against any opponents that were still intact.

The Spartans were well aware that success on the battlefield could carry a special danger in the form of friendly fire. Helmets limited vision and the din of battle was deafening, causing hoplites to easily mistake friend for foe in the mixed-up ranks. Thucydides cited just such a tragic incident within the encircling Athenian right wing at Delium in 424 bc. One way the Spartans reduced this hazard was by adopting uniform gear so as to more easily identify each other in the heat of a confused melee. To this purpose, they wore highly visible tunics that were dyed crimson. Their cloaks might have been red as well; however, they rarely, if ever, took these cumbersome garments into combat. The Spartans also painted large devices on their shields for identification, the most famous being the Greek letter lambda. Looking like an inverted “V,” this was the first letter in “Lacedaemon,” which was the ancient Greeks’ name for Sparta.

Sneak attacks were not a staple of the Spartan army, but one did yield a victory at Sepeia in 494 bc. There, Sparta’s famously wily King Cleomenes was facing a slightly larger host from Argos. Arranging a temporary truce and camping opposite the Argives, Cleomenes set up a routine that included signaling meals with a horn. When the enemy stood down at the same time for their own food, he had his men charge and put the unprepared Argives to a horrific rout. Another Spartan commander who used a sneak attack to good effect was Brasidas at Amphipolis in 422 bc, where he was under siege from Cleon of Athens. Cleon had lined up for a return to his base after a scouting expedition when the Spartans surprised him by rushing out of the city in two detachments, cutting the Athenian column in half and defeating each segment in detail. Brasidas brought the opening phase of the Peloponnesian War to an end with the victory, although he himself died in battle.

Even the best armies sometimes find retreat unavoidable. The Spartans, having lost 300 picked men and a king in a rearguard action in 480 bc at Thermopylae, came up with a less costly way to withdraw—the marching box. First used successfully under Brasidas in 423 bc, this formation consisted of forming most of the hoplite infantry into a hollow rectangle, placing the lightly armed soldiers and noncombatants inside the formation, and then deploying the remaining hoplites fore and aft to meet any enemy threats. The marching box could retreat and defend itself from all forms of attack. Xenophon of Athens claimed credit for creating the arrangement during the famed “Retreat of the Ten Thousand” after the Battle of Cunaxa in 401 bc. However, it is more likely that Xenophon simply modestly modified existing Spartan protocol.

Athens as a Military Power

Regard for classical Athenians as fighters in general has lagged behind their fame as creators of democracy and masters of aesthetic culture. From antiquity to the present, the Spartans have had far greater martial repute. Yet Athens in its fifth century bc heyday not only fought more than three times as many battles as Sparta, but actually enjoyed a slightly higher overall rate of combat success. In fact, Athenians developed the largest and most sophisticated war machine in all of Greece and applied tactics as creatively as they pursued the fine arts.

Athens followed adoption of democracy in 510 bc with a period of rapid expansion. The Athenians kept pace with rising territorial commitments by greatly increasing the size of their military. Athens’ army went from a late sixth-century bc count of 3,600 armored spearmen to 13,000 citizen regulars on the rolls by 431 bc. Likewise, the Athenian fleet grew from 60 to 300 ships over the same period. Sparta could answer with only about half as many Spartan hoplites of its own and had no navy at all.

Short on cash and having severely limited citizenship, the Spartans relied upon a system of alliances. The Peloponnesian League gave them access to tremendous manpower, but had serious handicaps. Sparta often had to coerce or cajole reluctant allies into action. There was also danger that a balking ally might spark an unwanted and costly conflict. Indeed, Thucydides suggested that Corinth set off the great Peloponnesian War in just such a way. In contrast, Athens had full control over its own larger military, as well as those of other states that were much closer to being subjects than true partners.

As Athenian soldiers grew in number and strength, the Greek city-state also greatly boosted its number of horsemen. Their cavalry force grew from fewer than 100 riders to some 2,200 during the fifth century bc. This was the only contingent of its kind among southern Greeks and was quite large even by the standards of horse-rich central and northern Greece. Moreover, Athenians held an edge over other cavalry in mounted archers. Originally imported from Scythia, these deadly riders rose to 200-strong. Horses made easy targets for the javelins of opposing skirmishers. By using an alternative screen of swift horse-archers with longer ranging composite bows, Athens transformed its cavalry into one of the most dangerous and versatile in all of Greece.

The cavalry experience inspired Athenians to develop further skills to guard their flanks. These could be either natural or man-made barriers, the latter of which saw use at Marathon in 490 bc. Frontinus described the Athenians building a crude wooden barricade, or abatis, to stretch their front against a hillside and discourage a mounted enemy attack. Likewise, they exploited existing structures outside Syracuse in 414 bc to repel horsemen, and they did so again inside Athens at the Battle of Munychia in 403 bc. All the same, reliance on natural barriers was the more common tack. At Plataea and Mycale (479 bc), Eurymedon (466 bc), and Anapus (415 bc), the Athenians won victories with their flanks resting on seashore, streambed, or uplands.

Use of the bow was even more particular to Athens than expertise at either cavalry warfare or flank barriers. Along with their singular deployment of mounted archers, the Athenians were alone among Greeks in sending out large numbers of bowmen on foot. Their army included 800 foot archers who fought in tandem with 300 specially trained hoplites. The latter arrayed three-deep at the front, kneeling while shafts flew overhead and standing to repel any attempt to get at the bowmen behind them. Such specialized troops played a major role at Plataea, where they turned back Persian cavalry.

In addition, 400 to 500 archers also served aboard the Athenian fleet. Unlike other Greeks, who piled up to 40 hoplites onto each ship for hand-to-hand combat with other vessels, the Athenians used just 14 marines (10 hoplites and four bowmen) and pioneered the art of combat seamanship. This called for maneuvering their ships into position to strike opposing vessels with an armored prow while pelting them with arrows. Whether on land or sea, Athens made better use of the bow than any other city-state.

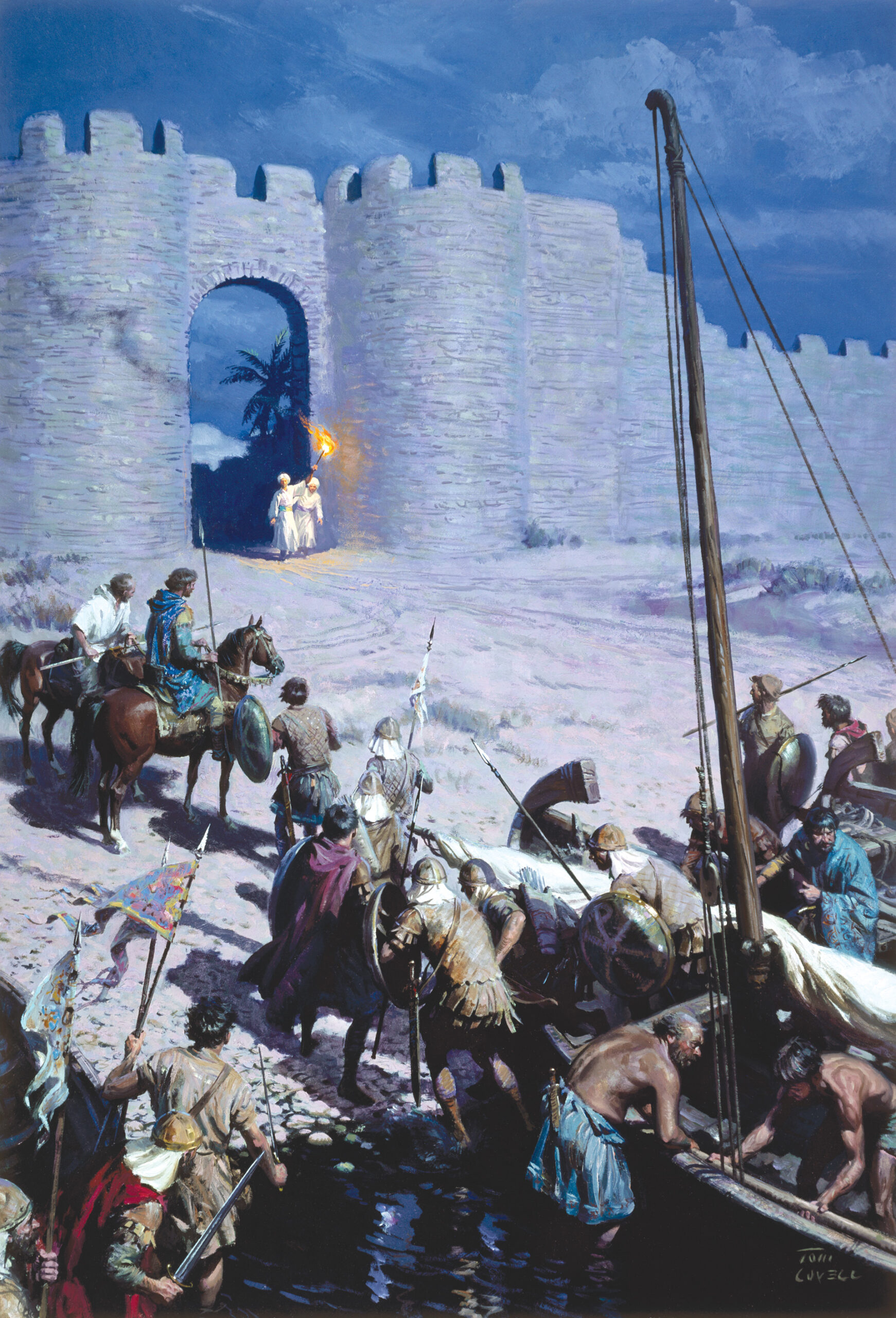

Athens’ superior fleet came into play for surprise operations. By taking advantage of its great amphibious capacity, Athens launched more unexpected offenses than any other Greek city-state. Seaborne landings had been common as far back as the Persian Wars. But combining them with a strong element of surprise arose in mid-fifth century bc as a tactic of the Athenian commander Tolmides, who sailed around the Peloponnese to descend for unexpected strikes against out-matched opponents. The Athenians refined the scheme over time with the use of troop transports, replacing the upper banks of oarsmen on war galleys with a mix of Athenian soldiers, light infantry, and horsemen. A commander could then land to enormous advantage with a large and diverse armament at a time and place of his choosing. Moreover, in the unlikely event that effective resistance did arise, he could simply put back to sea at very little risk to himself or his men.

When it came to stealthy operations, the Athenians did not always depend on their naval strength. In 458 bc, a year before Tolmides made his first surprise attack from the sea, Myronides of Athens won two battles as a result of unanticipated overland marches. These came at Cimolia, east of Corinth, where he twice bested the latter’s regulars with forces thrown together from reserves, resident aliens, and local allies. This would not be the last time Tolmides won an engagement with an unexpected march. One year later, he led an army north to catch forces of the Boeotian League unprepared. In the wake of the subsequent victory at Oenophyta, Athens was able to dominate all Boeotia except Thebes for the next decade.

Masters of surprise operations, Athenians also excelled at stealth and deception on the tactical level. Their gambits included ambushes, sneak attacks, diversions, and disinformation. As early as Salamis in 480 bc, Themistocles tricked the Persians into a foolish naval offensive by leaking false plans. Such tactics saw their greatest use during the Peloponnesian War, when Demosthenes sprang an ambush that routed a larger phalanx at Olpae in 426 bc and carried out three separate nighttime assaults, winning the first two before suffering a ruinous defeat in the last.

Demosthenes was a daring leader, but more cautious men also used tricky tactics on Athens’ behalf. Although notoriously conservative, Nicias used trickery twice to safely land armies on hostile soil, the first time with a diversionary attack and the second by feeding false information to the enemy. And a team of Athenian generals employed several deceptions at Byzantium in 408 bc. Xenophon and Diodorus detailed how they withdrew at night from a siege, only to sneak back and assault the docks with lightly armed troops. They then took the city by means of a surprise entry by their hoplites through an inland gate. Athenian commanders were not above deceiving their own men.

Myronides at Oenophyta fooled the hoplites on his right wing into thinking that their stalled left was already victorious. This inspired them to renewed effort that carried their side of the field and turned Myronides’s phantom success into the real thing.

Perhaps the least known aspect of Athens’ military prowess was its record of successful combat experience. One great truth of war is that victory often comes less from destroying a foe than from breaking his will to fight. This was glaringly apparent on the battlefields of ancient Greece, where comparatively few soldiers fell face-to-face, but many died after one side wavered and tried to run away. Being confident in their leadership, comrades, and personal ability gave hoplites the morale needed to impose their will on an enemy. Over a third of all the significant land engagements waged by Greek hoplites during the fifth century bc were Athenian victories. In fact, Athens’ victory total over this period more than tripled that of any other city-state and exceeded Sparta’s by a factor of better than four. Thus, when Athenians went into action, they fully expected to win—and more often than not they did.

All of the unique aspects of Athenian warfare came together in service of a fresh strategic concept developed by Pericles at the start of the Peloponnesian War to deal with the huge armies that Sparta and its allies could field. Athens hoped to avoid apocalyptic phalanx battle in favor of small actions and inflicting long-term economic pain. Exploiting its signature tactical skills and setting up fortified outposts (epiteichismoi) on enemy soil, Athens nearly brought down Sparta. It was only after the Spartans adopted key elements of the Athenian approach that they finally claimed victory after nearly three decades of war. Still, they could not suppress Athens for long and gave up a hotly contested occupation of the city after a single year. The Athenians soon had a fully restored democracy and went on to rebuild their overseas empire, rising up early in the next century to again challenge Sparta for supremacy.

It was rare for Spartans and Athenians to actually contest the same ground. This happened fewer than a dozen times during the entire fifth century bc. When these meetings took the form of grand, set-piece battles, Sparta always came away with the victory. Smaller engagements were more frequent and resulted in an unbroken string of Athenian successes. These seemingly contradictory trends were direct reflections of the states’ differing tactical approaches.

First Battle of Tanagra

Only three large battles in the fifth century bc saw Spartans and Athenians on opposing sides. The first occurred in 457 bc, when Sparta’s Nicomedes led an army of his countrymen and allies into Boeotia in a powerful demonstration meant to discourage Athenian aggression against Thebes, a Spartan ally. Athens responded in kind, and an engagement

(Tanagra I) took place that involved over 25,000 Spartan hoplites. As the battle unfolded, Spartan spearmen carried the day on their right with the help of traitorous Thessalian horsemen who deserted the Athenians just as the fighting began. Athenian hoplites, standing on their right, were equally successful; however, they abandoned the field to go after their beaten foes. As a result, the Athenians ultimately lost to a more disciplined Spartan phalanx that held on to the battleground.

First Battle of Mantinea

It would be nearly two generations before Sparta and Athens would again meet in a grand clash. This came about in 418 bc at Mantinea I, where Argos sought to contest local Spartan dominance with help from the Athenians and other allies. After several false starts, the two sides finally came to blows with over 17,000 hoplites. Spartan King Agis opened the action with a bungled maneuver that allowed Argos’s men to pierce and rout his left wing. However, when the Argives made the mistake of chasing the defeated men, Agis enveloped the Athenian soldiers on the opposite flank. As he did, Argive troops at center and next to Athens’ contingent lost their nerve and ran away at first contact with the Spartans. Their flight left the Athenians with enemy spearmen closing from both sides, compelling them to retreat at heavy cost. The battle ended with the Spartans reforming in place to rout the Argive right wing as it came back from its ill-advised pursuit.

Battle of Halae Marsh

The last large engagement between the two dominant city-states came when the Spartans ousted the democratic regime at Athens after the Peloponnesian War and set up an oligarchy to run the city, supporting it with mercenaries and a few of their own hoplites. In 403 bc, Spartan King Pausanius reacted to growing Athenian opposition by leading a surge of fresh troops into the city. He then inadvertently stumbled into battle on a narrow stretch above Halae Marsh, a small coastal swamp south of the main harbor at Athens. Some 7,500 Spartan hoplites engaged 3,000 Athenian spearmen across the restricted space. Many of the Athenians had only makeshift gear, but with their flanks anchored next to the wetlands and a rising slope, they made a spirited fight of it.

In the end, Pausanius’s deeper files finally pushed their way to victory. As usual, the Spartans did not give chase. This time, their restraint not only limited casualties but also garnered good will that allowed Pausanius to negotiate a peaceful withdrawal. This left his old enemies at Athens free to regroup yet also secured his main goal of ending the physical and fiscal drains that the occupation had been inflicting on Sparta.

Making good use of well-drilled tactics, Sparta’s superb hoplites had intimidated their foes, maneuvered around formation flanks, and held onto conquered ground to whip the Athenians in every grand-scale meeting over the course of better than half a century. However, they were not able to duplicate this feat in lesser engagements, whereas Athens could better employ its own signature martial skills.

Still, even smaller successes could have significant impact, such as the first three that Athens gained over Sparta earlier in the Peloponnesian War. These began in 425 bc on Spaectaria, a narrow island off southwestern Greece, where the Athenians bested a stranded Spartan garrison. They accomplished this with a landing near dawn that put perhaps 1,000 heavy spearmen and over 1,500 light-armed troops ashore against only 420 hoplites. Holding back from hand-to-hand fighting, this huge landing party drove the Spartans to the northern tip of the island under a rain of javelins and arrows and finally forced their surrender.

Within a year, Athenian soldiers were decisive in two more modest victories over Sparta. The first was on Cythera, just off the Spartan mainland. Nicias of Athens launched a sudden assault from the sea against this island’s port to divert attention from a landing with perhaps 2,000 hoplites. Heading inland, he then met a Spartan phalanx half his strength near Cythera’s capital. As had occurred so often, the Spartans advanced to put up a good fight despite being thinly filed. But the Athenians, veterans of many past victories, were not awed. Keeping their poise, they pushed back with files twice as deep until they drove their foes into retreat.

Nicias sent the surviving Spartans home under truce and turned Cythera into a base for amphibious raids all along Sparta’s coast. His foes had little chance to intercept the swift and unannounced attacks, and when they did, they met overwhelming opposition. Thucydides reported that a small Spartan garrison near a couple of coastal villages came to blows in contesting one such landing. Having perhaps no more than 300 hoplites, the defenders met quick defeat against what was very likely three times as many Athenian spearmen. The stinging reverse, added to those on Spaectaria and Cythera, dampened the Spartans’ ardor for war and induced them to offer peace, only to meet rejection from an increasingly confident Athens.

The Athenians wrested three more small victories from Sparta later in the Peloponnesian War. The first occurred in 411 bc, when the Spartan monarch Agis led a large column toward Athens in hope of exploiting political turmoil there. Some 600 hoplites of Sparta’s Sciritae regiment composed the king’s vanguard and, when this unit got too far out in front, came under attack. The Athenians pounced on the Sciritae with a mixed force of hoplites, light infantry, and cavalry. Unable to fend off an assault on every front, the Spartan spearmen made a fighting retreat, taking heavy losses in the process. By the time help reached the scene, the Athenians had already swept the field and returned home with the bodies of the fallen.

Thoroughly discouraged, Agis called off his offensive and arranged a truce to recover the remains of his lost men. He tried again, this time managing to reach Athens. There, however, he came up against a phalanx that kept close beneath the city wall, where it had excellent support from archers lining the ramparts above. Judging that he would take unacceptable casualties before even coming to grips with the opposing hoplites, the king simply turned about. As he marched off, his rear ranks fell behind and drew an attack from Athenian soldiers and horsemen.

The Spartans’ last setback of the war against Athenian troops came in 407 bc on the Aegean island of Andros. There, a landing force under Alcibiades of Athens surprised and beat a garrison half its size. The Spartans, who stood center and right in a thinly filed array, lost when local allies gave way on the left.

Two Unique City-States, Two Unique Ways of War

Accounts of actual combat between Sparta and Athens at their height make it clear that each had a fair share of success against the other. The Athenians used their expertise at surprise mobilization, amphibious operations, and light-armed warfare (both mounted and afoot) to achieve a greater number of victories. But Sparta’s hoplites plied their own deadly skills to win every large action. Any advantage in tactics that either could claim was fleeting, the temporary product of unique circumstances holding sway on a given battlefield. The century closed after long decades of bloody fighting very much as it had begun, with both Sparta and Athens still fiercely independent and equally powerful in their different approaches to war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments