By Kevin M. Hymel

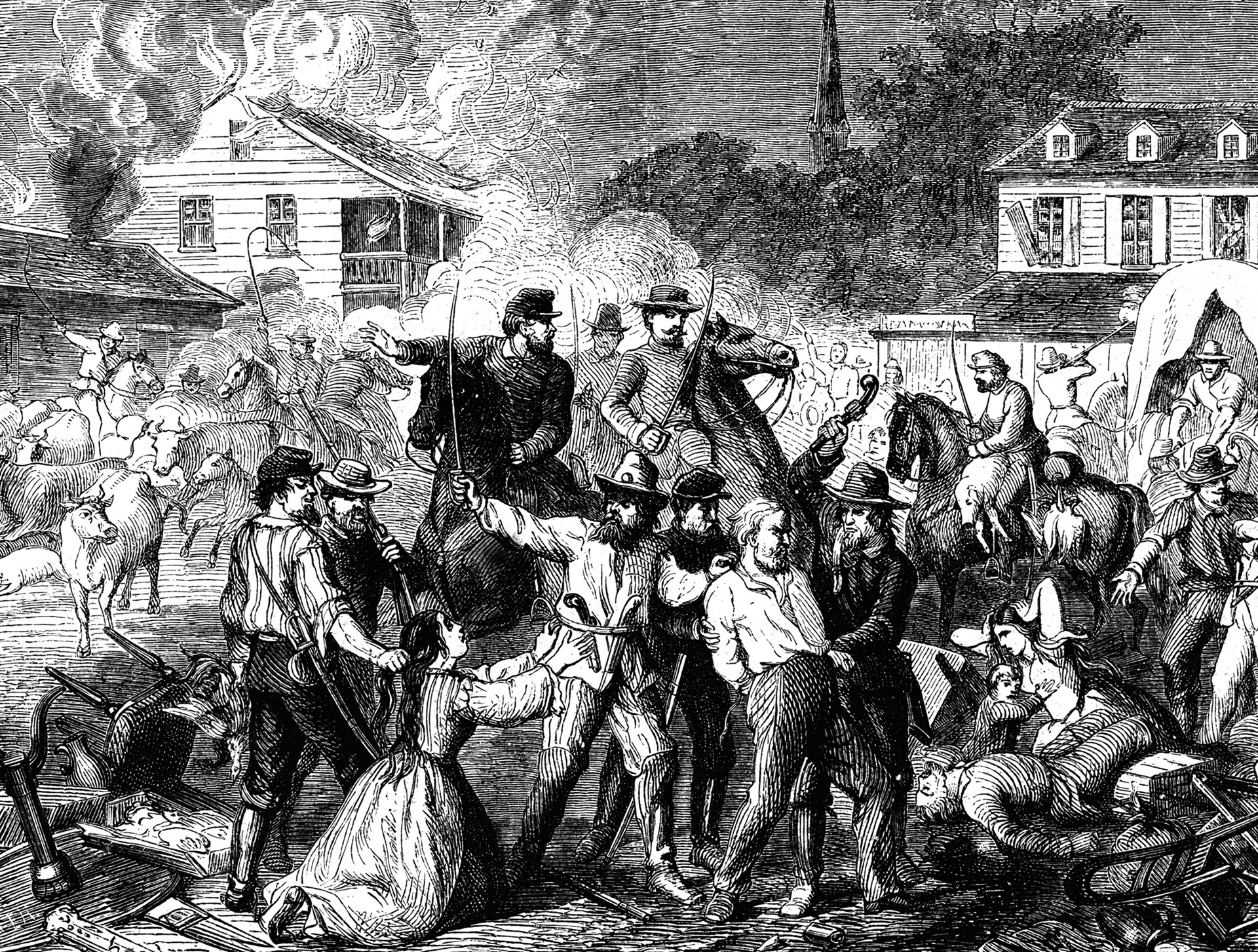

The German push west came to a violent end.

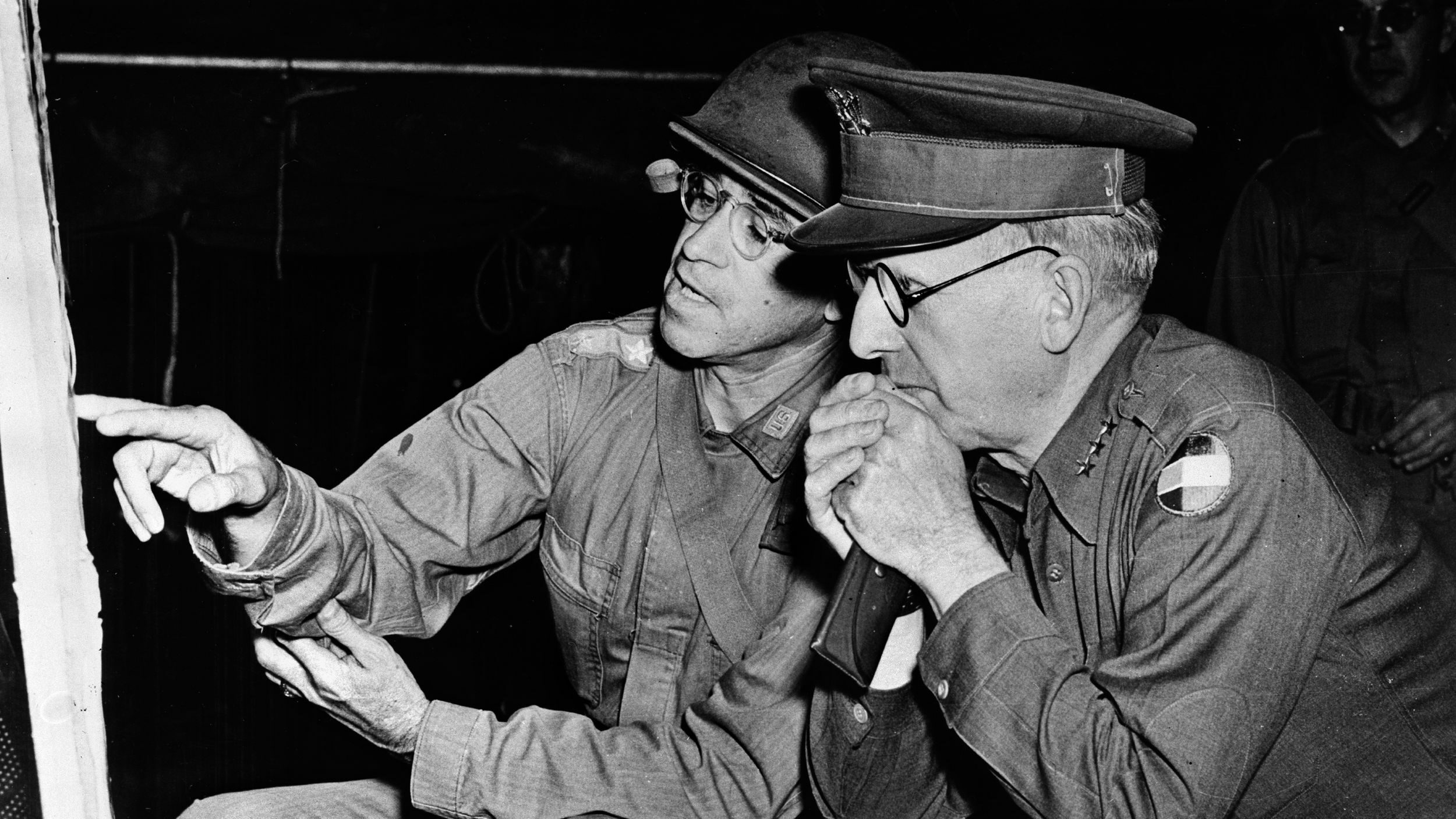

On December 19, 1944, the Panther and King Tiger tanks of SS Lt. Col. Joachim Peiper’s battle group smashed into the American tanks and tank destroyers of Lt. Col. George Rubel’s 740th Tank Battalion outside the Belgian town of Stoumont. The Americans quickly knocked out three Panther tanks and stopped the Germans’ progress. The Battle of the Bulge had reached its peak.

Four days later, Rubel’s battalion helped drive Peiper out of the town of La Gleize, two miles east of Stoumont. While the rest of the unit attacked, Rubel organized his assault tanks in front of a chateau and provided covering fire.

Inside one of those tanks was Private Harry F. Miller, passing 105mm shells to the gunner, who banged away at targets while Rubel stood atop a chateau wall directing fire. “He would tell us, ‘Left two meters, down one meter,’” explained Miller. “We’d fire and he would tell us when to quit.”

Miller had been with the battalion for only a month but was already a veteran. A native of Columbus, Ohio, Miller had always wanted to join the Army—his patriotism had been inspired as a kid while watching local World War I veterans march in parades. Miller was the youngest of six children—three boys and three girls.

His childhood during the Great Depression had been made all the harder when his mother died when he was three. His father repaired adding machines for the Burroughs Adding Machine Company until he lost his job. To make money, Harry delivered newspapers while his father repaired typewriters, but refused charity.

When Miller and one of his brothers brought home a can of corned beef they received from a charity group, their father demanded to know where they had gotten it. “Get it out of here!” he told them. “He was so proud,” explained Miller. “He wouldn’t go on welfare.”

A few months after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Miller was about to leave on his newspaper delivery route when he looked back through the home’s glass door and noticed that his father looked ill. Miller asked another boy to take his route, explaining that he thought his father was going to die that day. His premonition proved correct. Without parents, Miller’s oldest sister, nine years his senior, raised him. “I considered her my mother,” he said.

Miller joined the Army’s Enlisted Reserve Corps at age 15, claiming he was 18. He soon applied for active duty and was assigned to Fort Knox, Kentucky, for basic training, then to Fort Ord, California, where he joined an amphibious tank unit.

He trained on every position in the M4 Sherman tank, spending most of his time as either a loader for the turret cannon or the bow gunner. “Don’t bother unpacking your bags,” one of his superiors told him, “you’re going to Europe.” Sure enough, he was assigned to move some Landing Vehicles Tracked (LVTs) east, which were then loaded onto a Liberty ship, with Miller included.

Miller’s ship arrived at Le Havre, France, in late September 1944, three months after D-Day, and he was deposited in a replacement depot named Camp Old Gold. Soon, an officer told him and his fellow replacements, “You’re going to Third Army,” and gave everyone Third Army patches, which Miller sewed on without much enthusiasm. “I never thought much of [General George S.] Patton,” he recalled of the Third Army’s commander. “I didn’t care for his bravado.”

Instead, Miller was assigned to Lt. Col. George Rubel’s 740th Tank Battalion, the “Daredevil” battalion, in Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ First Army. In World War II, independent tank battalions supported infantry divisions. Unlike armored divisions, where tank battalions worked together, infantry divisions split up their tank battalions, with tanks being allotted to infantry units as needed.

Whereas armored division tankers were told to “haul ass and bypass,” independent tank battalion tankers moved at the pace of the infantry and destroyed resistance points that were holding up the advance of the foot soldiers.

When Miller joined the 740th, it was encamped at Aubin-Neufchateau, Belgium, about 10 miles west of the German city of Aachen. The battalion originally had been a special unit, equipped with Canal Defense Light (CDL) tanks.

CDLs, secret weapons developed by the British, were powerful carbon-arc searchlights for night attacks and to blind the enemy. Called “canal defense lights” to hide their true purpose, American CDL tanks housed their carbon-arc lights behind two slits in the turret. According to Miller, “They’d shine the light into a concave mirror and the operator would blind the Germans.”

The unit arrived in Belgium without tanks but was waiting for action. The officers lived in a castle while the enlisted men occupied school buildings, homes, and tents. The tank crews were mostly farm boys and ranchers.

When Miller arrived in mid-October, he was told, “You’re in Headquarters Company and the assault gun platoon,” but since there were no tanks, he trained in map and compass reading and kept his head down. “You’re the new guy and they’re not too sure they wanted to be with you,” he explained. “I kept my mouth shut; that way, I got along.” To look older, he smoked a pipe, though pipe tobacco was hard to find in war-torn Europe.

Each tank battalion contained an assault gun platoon that normally included six 105mm-armed M4A3 Sherman tanks—known as the M4A3 105 HVSS—which sacrificed anti-armor capability for the larger barreled 105mm cannon instead of the standard 75mm. They were used for infantry and assault support. Miller was assigned to one of the 105mm assault tanks.

As November turned into December, Miller often watched V1 rockets flying on their way to Antwerp. The unmanned rockets fascinated him. “It didn’t look like an airplane,” he said, “but it made a ‘chunk, chunk, chunk’ sound.” Hence the nickname “Buzz Bomb.”

On December 18, Miller’s unit was finally ordered to the ordnance vehicle depot at Sprimont, where crews would draw their tanks. Two days earlier, three German armies had broken through the Allied lines in Belgium and Luxembourg and were charging west—the Battle of the Bulge.

The tankers arrived at the depot to find numerous damaged tanks. Men were assigned tanks and told to find parts, often taken from other tanks. “Some of the tanks didn’t smell too great,” recalled Miller. “Dead bodies had been in them for a while.” It was a smell he never forgot.

The next day, December 19, anyone who had a functioning tank was ordered to the Stoumont railroad station where elements of the 30th Infantry Division were fighting. The men had managed to piece together three M4 Sherman tanks and an M-36 tank destroyer.

The small tank force knocked out three of Peiper’s Panthers—the spearhead of the 1st SS Panzer Division attack—and halted the German counteroffensive.

Meanwhile, Miller and the rest of the men, who could hear enemy fire in the distance, worked feverishly to get their tanks ready for combat. Miller recalled that as long as the sounds of the battle stayed away, he was happy.

Two days before Christmas, Miller and his crew finished repairing their tank and drove it out of the gate. “Everybody was scared,” he remembered. “Their eyes were bugged out.” Miller’s tank and five other 105mm Shermans rolled down a road bordered by woods and fields, to Chateau Froid Cour on the eastern outskirts of Stoumont. Less than two miles to the west, the Germans were making their stand in La Gleize.

It was during this attack that Lt. Col. Rubel stood atop a chateau wall and directed fire. When Rubel spotted an artillery crew driving east with a towed 155mm cannon, he stopped them and had them set up behind the chateau, where they added their Shermans’ 105mm fire.

As the tank’s loader, Miller found the 105mm rounds surprisingly heavy. He also could not see the effects of his Sherman’s fire, since the targets were too far away on the other side of a forest. He only saw explosions and La Gleize’s church steeple.

Rubel’s six 105s and one 155 shelled the town for about an hour, which had a profound effect on Miller. “It ruined my hearing!” he said. “I couldn’t hear worth a damn.”

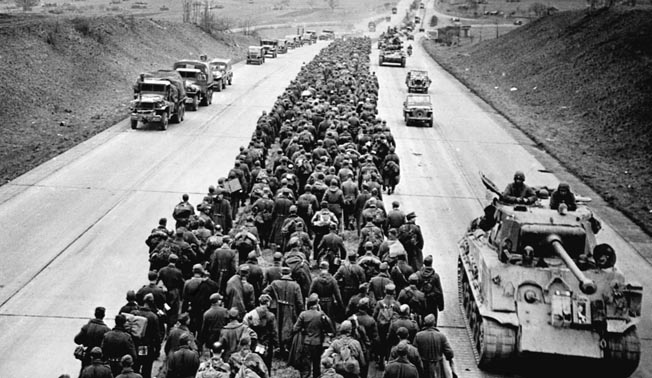

The next day, Miller and his tank crew headed into La Gleize. “It was a mess,” he recalled, “everything was down.” Bodies lay strewn everywhere in the rubble, Tiger tanks and other panzers remained smoldering where they had been knocked out, but the church, although badly damaged, still stood. The only sign of life Miller saw was an American tank crew refueling next to the city hall. The Germans were retreating.

While Miller never faced off against the Germans’ vaunted Tiger tanks, they haunted him. “We were scared to death of them,” he admitted. Other tankers told how its powerful 88mm cannon could easily penetrate any American tank’s armor. “It scared the crap out of me.”

Although the Germans were retreating, the fighting continued. As snow fell, the 740th continued to support the 30th Infantry Division. Miller switched to the bow gunner position, sitting in the front of the tank next to the driver and firing the 30-caliber machine gun. He recalled firing once at some escaping Germans on the side of the road.

When he learned that Peiper’s men had killed American prisoners of war at a crossroads called Baugnez—an incident known as the Malmedy Massacre—it changed his attitude toward the Germans. “The 1st SS was such a bunch of mean bastards,” he said.

The brutality of war disturbed the young tanker. Once, on a narrow road, his driver rolled over some dead bodies. Miller did not know if they were Germans, Americans, or Belgians. The man standing in the turret did not look back to see the effect.

“You can’t stop the column of tanks so you can go around them because the street is too narrow,” he explained. “You roll over [the bodies], but it gets to you.” He also saw burned bodies in destroyed tanks, but it was the smell that really bothered him. “If you dwell on that sort of stuff, you’d be climbing the walls.”

There were no celebrations on Christmas Day. Instead, the unit hooked up with the 82nd Airborne Division, where Miller’s platoon fired missions for the different parachute infantry regiments. Whenever the paratroopers needed indirect fire support, Miller and the other assault tanks would spread out in a field or along a tree line and fire away at targets. If they engaged in an artillery duel with the Germans, the crews draped camouflage netting over their tanks.

“The 82nd liked us,” Miller said, “and we stayed with them through the Bulge and to the Siegfried Line.”

Much of the fighting occurred in deep snow with overcast skies. The men tried to keep warm, often wearing multiple sweaters under their tanker jackets. “I had to beg, borrow, or steal blankets,” recalled Miller. If he ever rode in a jeep, he stuck his legs into U.S. mail bags to keep warm, something the driver could not do. One day, out of boredom, he counted 20 different kinds of coats worn by his fellow tankers.

When Miller could sleep, he usually did it inside the tank. If it was warm enough outside, he slept under the tank in case of an enemy artillery air burst. He never lacked new clothes. As one of the skinniest men in the battalion, he could wear almost anything. “The supply sergeant always gave me spare shirts and pants,” he explained, “because he didn’t want to haul them around.”

For food, Miller liked the Ten-in-One rations, but detested C-rations, canned rations, and D-bars—melt-proof chocolate made especially for the Army. “I hated all of them,” he said. Whenever possible, the men enjoyed hot food prepared by their cook, a soldier named Flood. “He could put together some good meals,” recalled Miller.

The men often shared their food with Belgian children. “Having been through the Depression myself, I felt sorry for them,” he explained. Unlike Miller, the children surprisingly liked D-bars. “Compared to Belgian chocolate, it was trash.” Yet the free candy bars brought smiles to the children’s faces. “You’d thought we’d handed them a thousand-dollar bill.”

The men stole booze wherever they could, mostly from people’s basements. The only problem was lugging the bottles and hiding them where they could not be stolen again. “If it had the date of 1800 on it,” Miller said, “you couldn’t wait to pop that open.”

At the end of January 1945, Rubel’s unit reached Germany and fought its way across the Siegfried Line, Germany’s last man-made defense. Miller watched as a tank dozer shoved dirt over the concrete pylons known as “Dragons’ Teeth,” allowing tanks and other vehicles to drive over the barrier.

On February 4, the battalion was taken off the line for a break, but the rest proved short lived. Two days later it was transferred to the 8th Infantry Division in a different corps area. Once with the 8th, the Daredevils pushed forward to the city of Düren and the Roer River.

Düren had been destroyed by constant Allied bombing and artillery barrages. “It looked like a pancake,” recalled Miller. But, when the Americans reached the Roer River, they found that they could not cross it. Rains, melting snow, and destroyed dams in the south put the river at flood level.

“There was nothing we could do,” he said. “We couldn’t get anything across.” Instead, the tankers completed maintenance on their vehicles. Occasionally, the Germans shelled the American side of the river and the Americans returned fire.

In the city stood a statue of Otto von Bismarck, Germany’s first chancellor, with an outstretched arm that had been pointing west, but heavy vibration from bombs and shelling had turned it so that his hand pointed east, like a signpost pointing the Yanks toward Berlin. “I was surprised no one knocked a finger off of him,” Miller said, “or knocked his hand off.”

While in Düren, Miller was transferred from the 105mm Sherman to working in the battalion’s message center. He operated out of a radio-supplied half-track with five other soldiers, relaying messages from the headquarters to the companies. Rubel radioed orders to Miller’s half-track, which he would hand deliver to the company commanders.

The work took him closer to the front than his tank had. “Every time you went closer to the front, you didn’t know if that would be the last day,” he said. “Every day was exciting.”

Miller often manned the half-track’s ring-mounted .50-caliber machine gun and would sometimes fire it at objects for fun. “I had to be careful ’cause I didn’t want to be caught.”

He noted, “It was scary going through towns,” as he worried about Germans dropping grenades into the half-track’s open bed from second-story windows. In bad weather, the men draped the bed with a canvas tarp. “It was hotter than hell in the summertime if you had it over you.”

Finally, on February 24, 1945, Rubel’s battalion crossed the Roer on a Bailey bridge. On the other side, Miller noticed that the flat terrain near the river rose to become a hill that overlooked the city of Cologne to the east. The unit then advanced through the south side of Cologne, where Miller did not see a single building standing—only rubble and the smell of dead human bodies and fallen horses.

“We would go past a bombed-out building and we knew there were dead bodies in there,” he recalled. “That’s a smell you never forget.” Dead bodies were one of three odors he identified with war. “That,” he explained, “and horse shit and gasoline.” Manure piles stood in almost every German town and farm.

Whenever the skies cleared, Miller saw fleets of bombers on their way to Germany. “They looked like an aluminum overcast,” he said. He also saw crashed planes across the landscape, but they were always German, not American.

Miller was more impressed with American fighter planes, which he often saw flying in pairs or groups of three. Whenever the men spotted a dogfight above, they stopped and watched as though it were a spectator sport. Closer to the ground, American fighter aircraft dove on German roadblocks ahead of attacking columns and sometimes swung back around hit their targets a second time.

Their pilots’ favorite targets were German trains and railroad stations. “I remember seeing railroad tracks tied in a knot from the blasts,” he said.

One day, Miller was heading down a road in the passenger side of a jeep when a North American P-51 Mustang fighter roared straight over, only yards off the ground. “He was low enough that if I hadn’t had my helmet on, my hair would have gone up,” he said.

After two weeks of combat, Lt. Col. Rubel expected a break for his tankers. Instead, he received orders to help the American Seventh Army crack the Siegfried Line, for a second time. The tankers headed west to the train station in Aachen where they put their tracked vehicles on flatbed railcars to travel south to Saarbrücken. The unit detrained and joined the 70th Infantry Division, but they were not needed. “We got there but they had already crossed [the Siegfried Line].”

The Daredevils then headed farther south to assist the 63rd Infantry Division’s crossing of the line. The battalion again faced Dragon’s Teeth and bunkers housing 75mm high-velocity antitank guns. “We had to punch through those damn bunkers,” said Miller. The unit continued to support the infantry until March 21, when it reached Homberg.

But now the battalion was needed up north. On March 30, the unit loaded onto trains once more, this time for the city of Bonn; the 8th Infantry Division had requested their help in closing the Ruhr Pocket. To reach the 8th, the battalion had to cross the Rhine River on a pontoon bridge at Bonn.

Miller did not like crossing such a powerful river on a floating bridge. “It was pretty much like riding a roller coaster,” he said of up-and-down trip between each pontoon. “You’d see [the vehicles ahead of you] going down, and hope they’re gonna go back up.”

The 740th then joined the fight. At one point some of the tankers took on the German Luftwaffe and won. The tanks happened by an airfield where enemy planes were taxiing onto the runway. “The German planes were trying to get off the ground,” described Miller. “Our tanks, as they went down the road, were shooting [at them] as they took off.”

The planes made it into the air, but before they could retract their landing gear, the tanks opened fire and the planes crashed back down to earth. The men cheered at the tankers’ marksmanship. “It was like a turkey shoot.”

Later, Miller saw something he thought strange: enemy planes hidden in forests along the autobahn, which pilots used as an airstrip. He saw an old Junkers Ju-87 Stuka, which had once terrorized Allied armies by dive-bombing with its siren tearing the air.

He also spotted a Messerschmitt Me-262, the war’s first operational jet fighter, which did not impress him. “It was an ugly looking airplane to me,” he recalled.

During the campaign, word came down on April 13 that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had died the day before. “Everyone was shocked,” said Miller, although the men who had seen the president in newsreels believed he looked sickly. “We thought he shouldn’t have taken that fourth term [as president] because he looked so bad.”

As the Battle of the Ruhr Pocket wound down at the end of April, the 740th was sent to Düsseldorf for occupation duty. The men used the two weeks off to clean their vehicles, refurbish their supplies, and rest.

Miller enjoyed himself, finding the German women prettier than the Belgian women. “German girls were hungry for men,” he said. Even though there were strict rules against “fraternization” with enemy civilians, Miller paired off with the 40-year-old widow of a German colonel. “She was nice looking,” he remembered, “and she had blond hair.”

On April 30, the battalion helped the 82nd Airborne and 8th Infantry Divisions cross the Elbe River. The Americans pulverized the east bank with artillery then crossed in small boats. Miller watched as Airborne engineers stretched a pontoon bridge over the river under fire.

Suddenly, the XVIII Airborne Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Matthew Ridgway, showed up, dissatisfied with the engineers’ progress. “He was having a fit and cussing,” said Miller. “He thought it was going too slow.” Soon enough, the enemy fire slackened, the bridge was completed, and men and vehicles crossed.

Once across the river, the 82nd raced ahead, spearheading the corps’ attack. “One of the tank commanders called back to say, ‘The 82nd is riding horses-and-buggies and they’re now passing me!’” said Miller. “Everything was hell for leather. It was go, go, go!” The war was nearing its end.

The battalion was then ordered to help the British Second Army and headed north to Schwerin to block the Russians from reaching Denmark; the battalion occupied a castle on Lake Schwerin. “We were on the west side,” recalled Miller, “and the Russians were on the east side.” The 740th Tank Battalion remained there until the war in Europe ended on May 8, 1945.

The war’s end was anticlimactic. “It wasn’t a big ruckus,” said Miller. “It was just a relief.” Soon, Lt. Col. Rubel assembled the battalion. After the chaplain said a prayer, Rubel spoke to the men: “We will all be leaving shortly and I hope we meet again,” he told them. Almost everyone wanted to go home except Miller, who had no one to go home to. His parents were dead, his oldest sister had married, and one of his brothers was in the Pacific.

War-torn Germany was filled with prisoners—German prisoners of war, freed Allied prisoners, and concentration camp survivors, now referred to as “D.P.s” or “displaced persons.”

Miller thought the German POWs were relatively docile, except the former SS. One day, a group of SS prisoners were threatening to break out of their enclosure and he and other half-track crew members were sent to quell the unrest.

The half-tracks arrived and spread out on a field across from the camp. The American officer in charge addressed the prisoners through a bullhorn. Then he fired a .50-caliber machine gun, stitching a line across the field, and announced that if they crossed the line they would be killed. “They calmed down,” recalled Miller.

The battalion transferred to Limburg, Germany, where the men spent their off-duty hours drinking. Men from the battalion’s D Company raided houses to confiscate weapons and booze. If they found any surplus cognac or champagne, one of the men would send it to Miller in a large black suitcase, which he would load into his jeep and hide in a nightstand in his apartment. “If I didn’t feel like going to the club,” he explained, “I could stay home and knock out a bottle of cognac or champagne—and knock myself out.”

The men also took over a nightclub. “It was the longest bar in the ETO,” said Miller. One of the tankers, a Cherokee Indian named Hummingbird, often drank too much and became violent. One night, Miller watched as two British soldiers approached Hummingbird and told him that Great Britain had won the war.

“I heard two hits and saw the Brits sliding straight across the floor.” Miller recalled. “MPs dragged the two out.” It was not the only fight he witnessed. Men heading home often got into fistfights over which army was better, Patton’s Third Army or Hodges’ First.

Miller was in Limburg listening to Armed Forces Radio when he heard the news that Japan had surrendered. “Everyone was beside themselves,” he said. The war was over. Miller stayed in Germany.

After the outfit broke up in June 1946, Miller transferred to the 9th Infantry Division at Bad Tölz in Bavaria, near an airplane hangar where German prisoners were processed.

To prevent suicides, the Germans were brought in groups of 40 into a large room where they disrobed and were sent to another room and given new clothes. Americans then shook out the prisoners’ clothing looking for weapons. “The Germans did not want to go home,” said Miller. “Their families were dead and their towns bombed out.”

Showing mercy on his former enemies, Miller sometimes gave his spare clothes to the hapless prisoners. His kind gesture had far-reaching effects. Decades later, his niece married an American soldier in Bad Aibling, Germany. While there, she asked an older German what he thought of Americans during the war. The man said he thought the world of an American soldier who gave him a shirt. When she asked the American’s name, he told her, “Harry Miller.” She later asked Miller about the incident, but he could not recall it, although the German had the correct dates and location.

When the 9th Infantry went home five months later, Miller transferred to the 2nd Constabulary Regiment, in Füssen, Germany, home of the famed Neuschwanstein Castle, which later served as the model for the Disneyland castle. Promoted to technician third grade (T/3), he worked in the message center.

When the Korean War broke out on June 25, 1950, Miller headed MacArthur’s alert crew, which went to Korea in advance of the general whenever he visited the battlefront. For his new job, Miller took glider training with 11th Airborne Division, until gliders were declared obsolete. “It scared the crap out of us,” he said. He described flying in a glider as “an instant cure for a lifetime of constipation.”

Miller left Japan in April 1951, about the same time that President Harry S. Truman fired MacArthur, and transferred to the Army Security Agency near Munich, Germany, but hated his new position. “The officers were the worst people,” he said. He volunteered for Korea but the Army refused because of his security clearance. He knew too much to risk capture.

Miller returned to the United States, where he joined the U.S. Air Force. “They gave me tech sergeant stripes and a blue uniform,” he recalled, “and I did the same thing I had done in the Army.” As a communications operations superintendent at Strategic Air Command in Omaha, Nebraska, Miller helped develop and distribute codes for B-52 bombers heading to Vietnam. He stayed in the Air Force until 1966 and retired as a senior master sergeant.

After serving his country for more than three decades in war and peace, Miller became a private investigator. Eight years later, he became the director of security and safety at St. Vincent Hospital in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

In 1969 Miller married a girl named Elva Mae “Billie” Hegsted, who had been a model and a stand-in for a movie actress. They adopted two boys, Harry Jr., born in 1954, and Joe, born in 1958. Billie constantly worried she had cancer, since it had occurred in her family. In 1975 she gave into her fears. Miller was at work when he got the same premonition he had had when his father died. He called home, but when Billie did not answer, he immediately went home and found she had overdosed on sleeping pills. She never had cancer.

Miller was despondent and alone when a nurse at the hospital invited him to her husband’s war reunion at nearby Los Alamos. He agreed, and she asked, “Is it okay if Helen goes with us?” Miller knew Helen Carrion, who looked like Rita Moreno and worked at the hospital. He agreed. The reunion included a large dance and Miller and Carrion danced every song together.

“I am telling you,” he stressed, “she was a good dancer.” Not wanting her to get away, Miller married her in 1975 and they stayed together until her death in 2012.

Miller always took pride in his World War II service and the men of the 740th. In early 1999, he was asked to design a memorial to the Daredevils for Aubin-Neufchateau. He and Helen designed a monument consisting of two Belgian blue stone columns connected with a slab of black granite. The names of the battalion members were etched into the columns.

A dedication to the people of Aubin-Neufchateau, written by Miller, was chiseled into the granite. “Those people really took to us and we stayed friends with them throughout the years,” he explained. The monument was unveiled on April 24 of that year.

Today, at the age of 89, Miller lives at the Armed Forces Retirement Home in Washington, D.C., popularly known as the Old Soldier’s Home. He proudly wears his blue World War II veterans baseball cap with the 740th patch and tank and jeep pins.

While he looks back fondly on his service, the horrors of war can always haunt him. Sometimes he wakes up with the smell of dead bodies in his nose. “I used to wonder, ‘Where did I have my nose that I smelled that in bed?’”

SMSgt (Ret) Miller was one tough man, like so many back then. Appreciate his service and sacrifice.