By Kevin Seabrooke

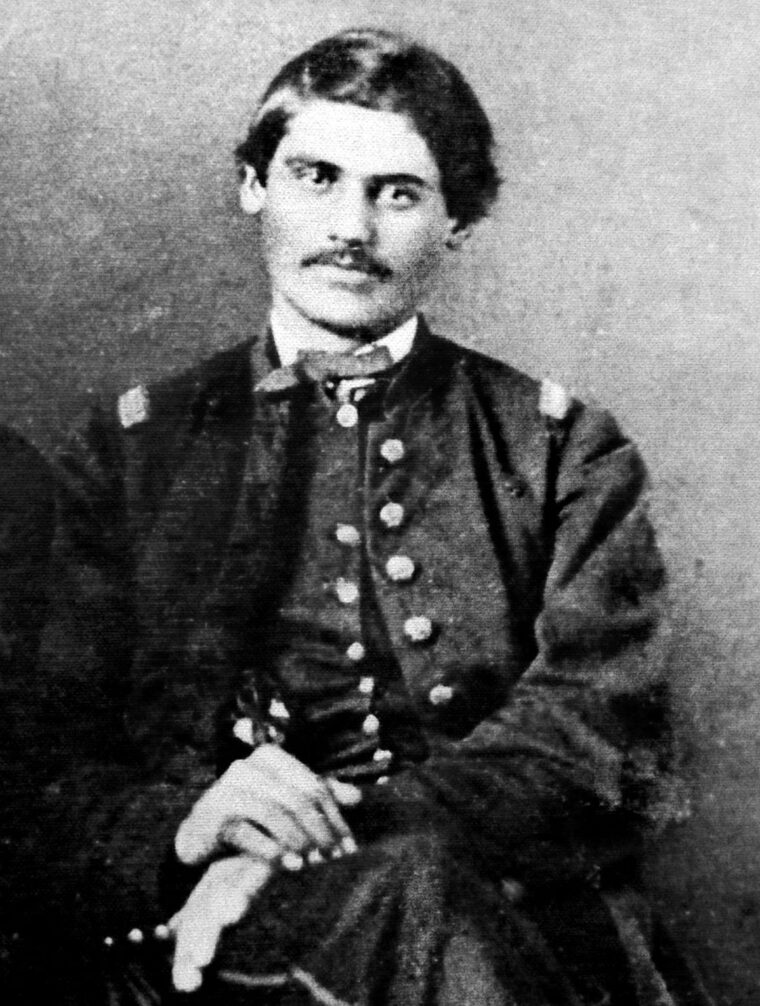

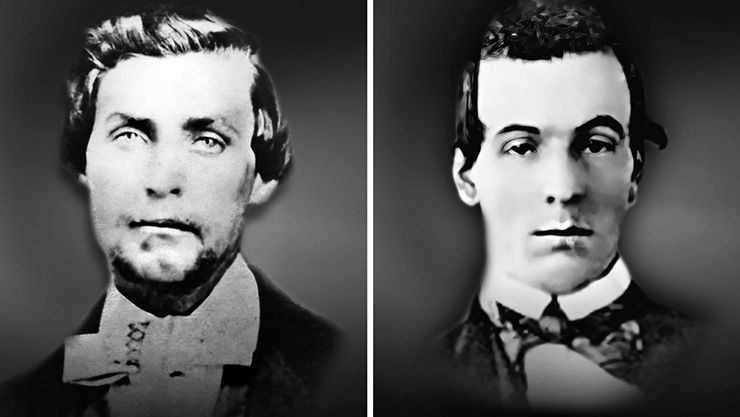

A little more than 162 years after they were executed as spies in Georgia, privates Philip G. Shadrach and George D, Wilson of the 2nd Ohio Infantry were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor by President Biden in a ceremony at the White House on July 4, 2024.

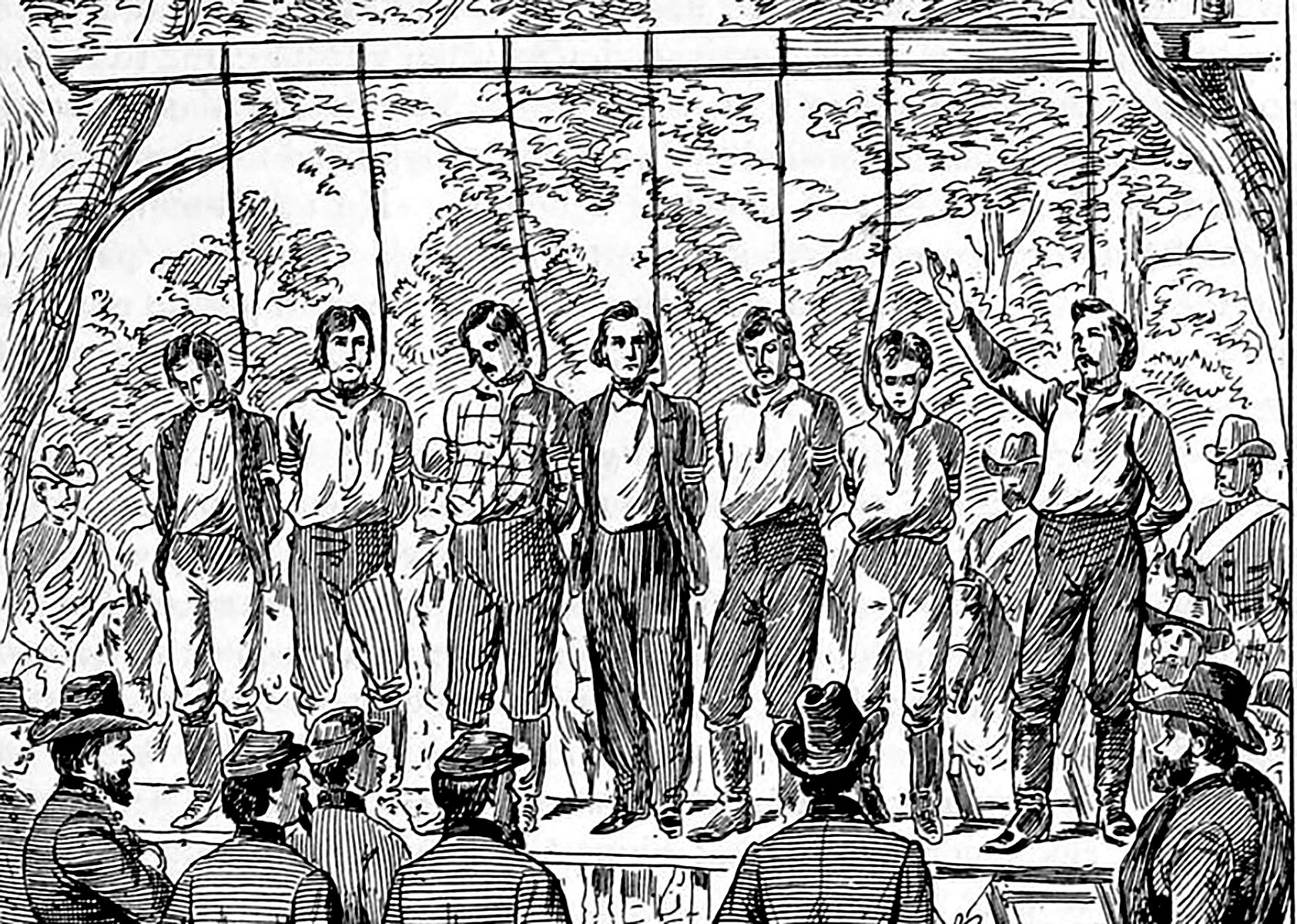

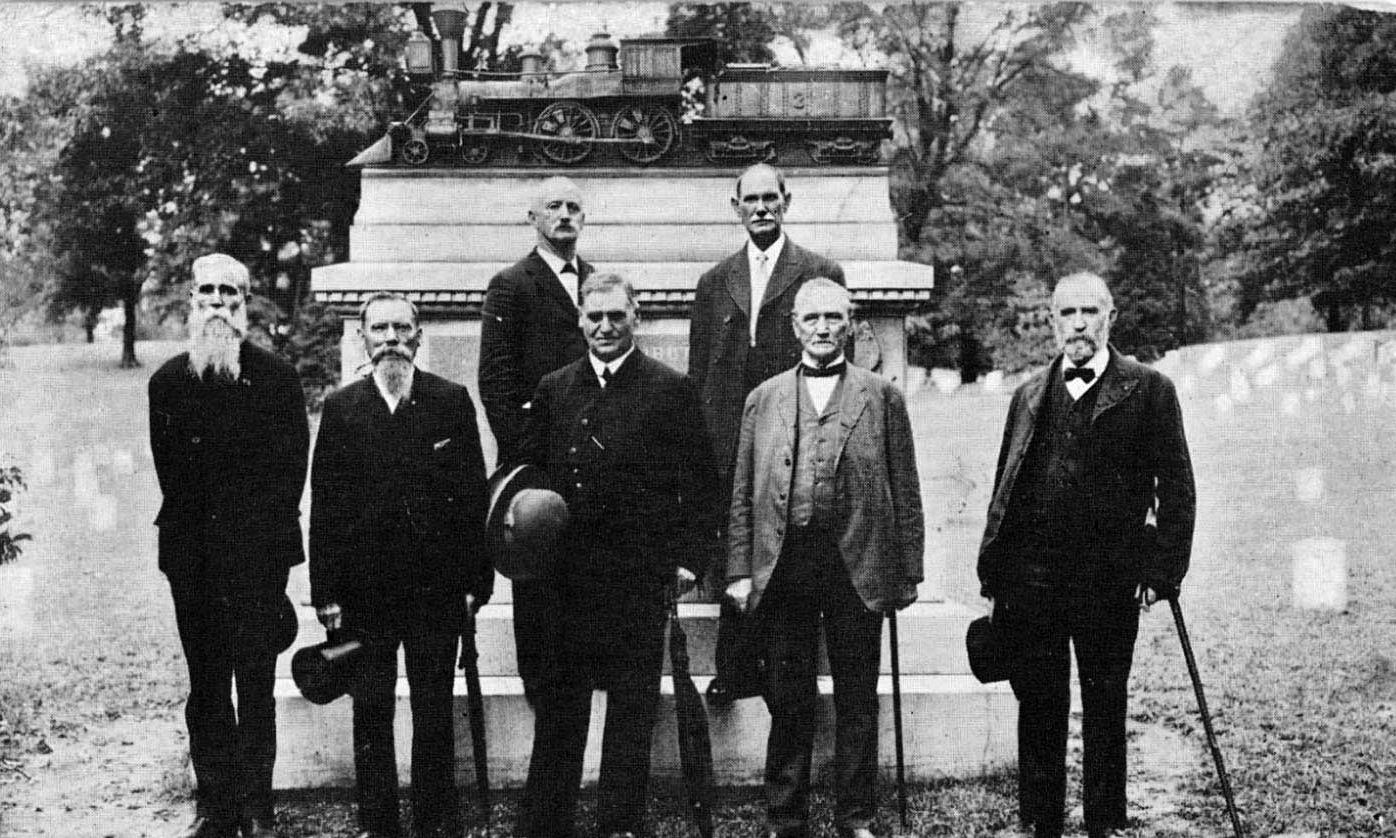

The privates were part of a group of seven men from Ohio who were hanged in downtown Atlanta on June 18, 1862. They had all taken part in the “Andrews Raid,” a covert military operation 200 miles behind Confederate lines more often known in the folklore of the Civil War as “The Great Locomotive Chase.” Twenty one other U.S. soldiers who took part in the raid were later recognized with the MOH—including Private Jacob Parrott, the first—but for reasons unknown, Shadrach and Wilson were overlooked. They were permitted to receive the medal as part of the fiscal 2008 National Defense Authorization Act. Another member of the raid who was hanged on June 18 was William H. Campbell, who, as a civilian, was not eligible for the medal. James J. Andrews, the Union spy who conceived and led the raid, was also a civilian. He was hanged in Atlanta on June 7, 1862.

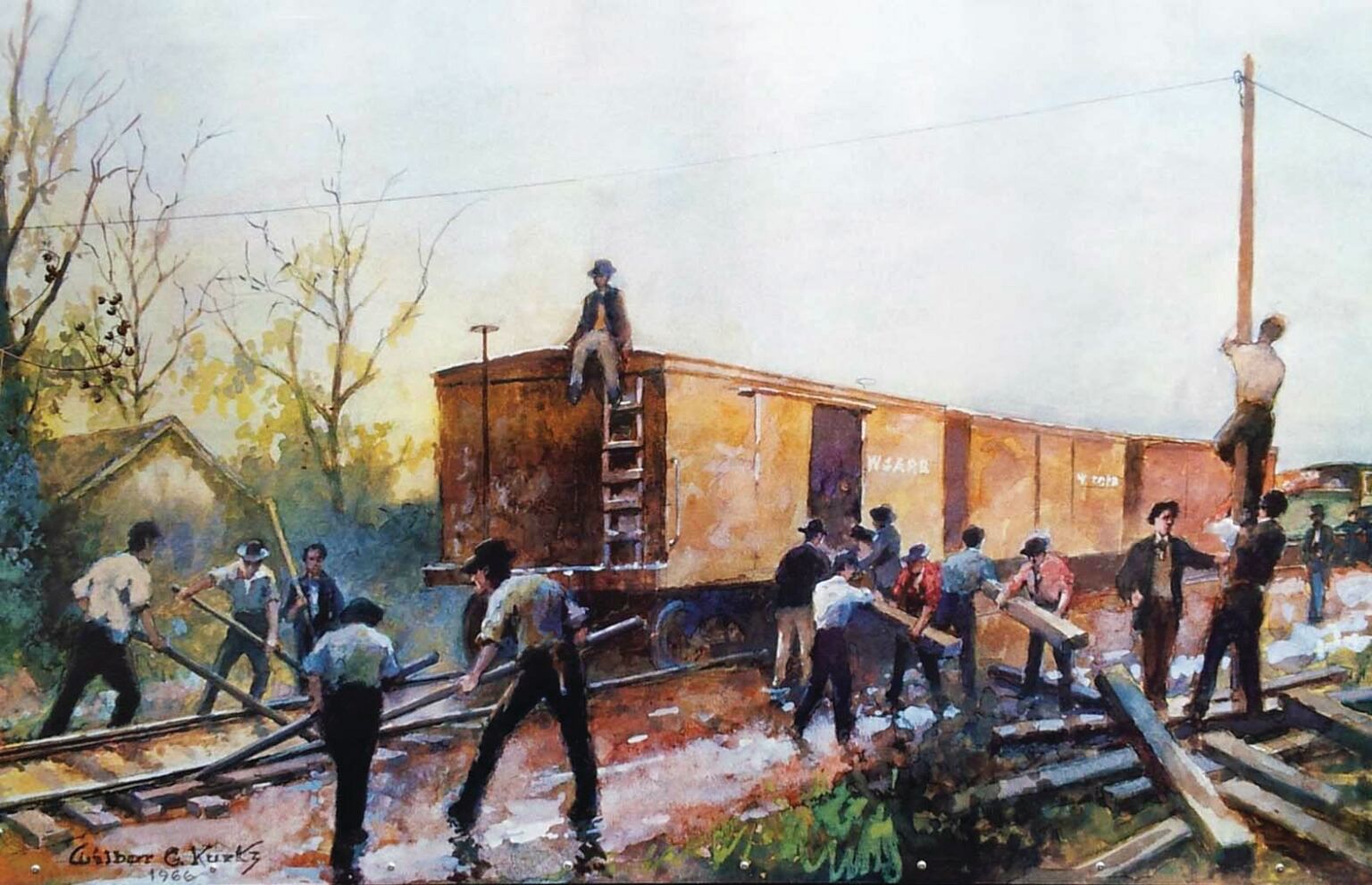

Andrews’ idea made some sense, at least on paper. A small band of volunteers would penetrate far behind enemy lines to the outskirts of Atlanta, steal a locomotive, then head for Chattanooga, Tennessee—cutting telegraph lines, tearing up track, and burning railroad bridges along the way. This would sever communication and supply lines, allowing Brig. Gen. Ormsby Mitchel to take the strategic city without fear of reinforcements arriving from the south.

Completed in 1857, the Memphis and Charleston Railroad was the first to link the Atlantic Ocean with the Mississippi River. During the Civil War, this line was considered by the Southern high command as the “vertebrae of the Confederacy.” Near the center of this line was the rail hub of Chattanooga, with the Western & Atlantic heading south to Atlanta and the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad north to Virginia. If the Union could capture Chattanooga, they would threaten Confederate forces for hundreds of miles to the east and west. But to do that, the line to Atlanta had to be disabled.

Always a significant factor in the Civil War, the struggle over rail lines ran especially hot in the spring of 1862. The bloody clash of Shiloh (April 6-7) that so shocked the nation with 23,000 killed was over the vital crossroad of Corinth, Mississippi, where the Memphis and Charleston intersected the Mobile and Ohio Railroad. The Union succeeded in capturing Corinth by the end of May helped, in part, by Mitchel’s capture of Huntsville, Alabama, severing the Memphis and Charleston line.

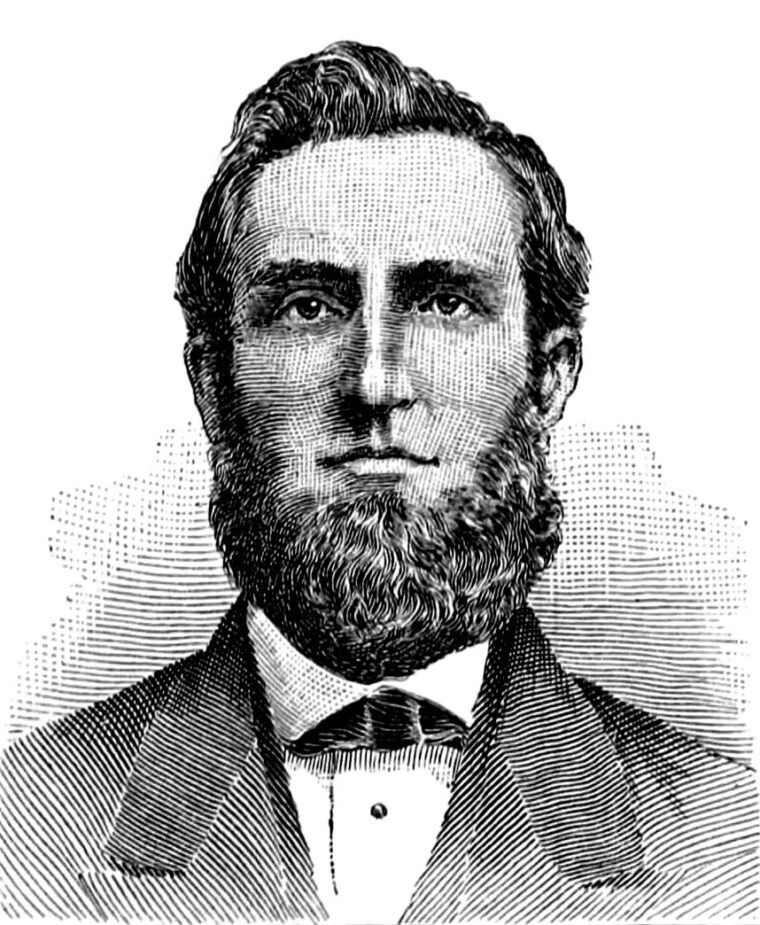

The raid was intended to happen in coordination with Mitchel’s attack on Huntsville, planned for April 11. In fact, such a raid had already been attempted just the month before, with a party of eight men, who were meant to meet a Confederate railroad engineer who would drive the locomotive for them. The man never showed up and after several days Andrews returned north. He later heard that the engineer had been pressed into service taking every available man to Corinth for the coming battle. Corporal William Pittenger, a raider who would later write several books about his experience, including, Daring and Suffering: A History of the Great Railroad Adventure, believed that with Confederate Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard’s attention focused on Mississippi, Andrews’ first mission might have succeeded. Andrews had first proposed the idea to Gen. Don Carlos Buell who, for unknown reasons, declined.

Only four of Andrews raiders, as they came to be called, knew anything about trains. None of them had any experience in espionage or sabotage—or even combat, really. Andrews himself had been smuggling quinine south to sell on the black market and bringing information back to the north. The men with him were a nearly random collection of soldiers from Mitchel’s 3rd Division of the Army of Ohio. Meeting on a farm near Shelbyville, Tennessee, the men were given Confederate money and told they needed to catch the last Western & Atlantic train out of Chattanooga at 5 p.m., heading south over the line they planned to destroy.

“No start to a long journey could have been less promising than ours,” recalled Pittenger. “The night was pitchy dark, the rain poured down, and the Tennessee mud was now almost unfathomable.” Even worse, Confederate troops were told to be on the lookout for Federal soldiers disguised as civilians. In fact, two of the Andrews men Priv. Ovid W. Smith and Corp. Samuel Llewellyn, never made it out of Chattanooga and were forced to join Confederate army to avoid detection. Smith would receive a MOH in July 1864. Llewellyn is now the only soldier in the original party to never received one.

Given the weather conditions, Andrews figured Mitchel wouldn’t be able to take Huntsville by the appointed time and delayed the mission by a day—a decision with dire consequences. For Mitchel had marched in the rain and taken Huntsville on time. Still in Chattanooga as they heard the shocking news, Andrews and his men would now have to travel with extra trains and mobs of people fleeing southward.

“The city was taken completely by surprise, no one having considered the march practicable in the time,” Mitchel reported. “ We have captured about 200 prisoners, 15 locomotives, a large amount of passenger, box, and platform cars, the telegraphic apparatus and offices, and two Southern mails. We have at length succeeded in cutting the great artery of railway intercommunication between the Southern States.”

One of the men with railroad experience, Private John Alfred Wilson, now saw little hope of success. “But it was too late now to change the program,” he recalled. “We must make the effort, come what might.”

Heading south on a train crammed with refugees and Confederates, the raiders saw many trains on sidetracks, all potential obstacles for them on the following day. They were in for another shock as they passed through Big Shanty (now Kennesaw, Georgia) where the train would stop for 20 minutes on the trip north the following morning to allow the crew to have breakfast. The place where they planned to steal the train was now home to a large military training camp.

They arrived in Marietta around midnight and took a couple of rooms at the Fletcher House to catch a few hours’ sleep before their early start in the morning. Corporal Martin Hawkins, the most knowledgeable train man, and Private John Porter had arrived earlier and were asleep at the Marietta Hotel across the town square.

In his second book on the raid, Capturing a Locomotive: A History of Secret Service in the Late War, Pittenger recalls the thoughts of Wilson of that night: “Our doom might be fixed before the setting of another sun. We might be hanging to the limbs of some of the trees along the railroad, with an enraged populace jeering and shouting vengeance because we had no more lives to give up; or we might leave a trail of fire and destruction behind us, and come triumphantly rolling into Chattanooga and Huntsville, within the Federal lines, to receive the welcome plaudits of comrades left behind, and the thanks of our general, and the praises of a grateful people. Such thoughts as these passed in swift review, and were not calculated to make one sleep soundly.”

When the morning came another pair of raiders was lost as the hotel clerk failed to wake Porter and Hawkins on time and they missed the train. The party was now down to 20 men.

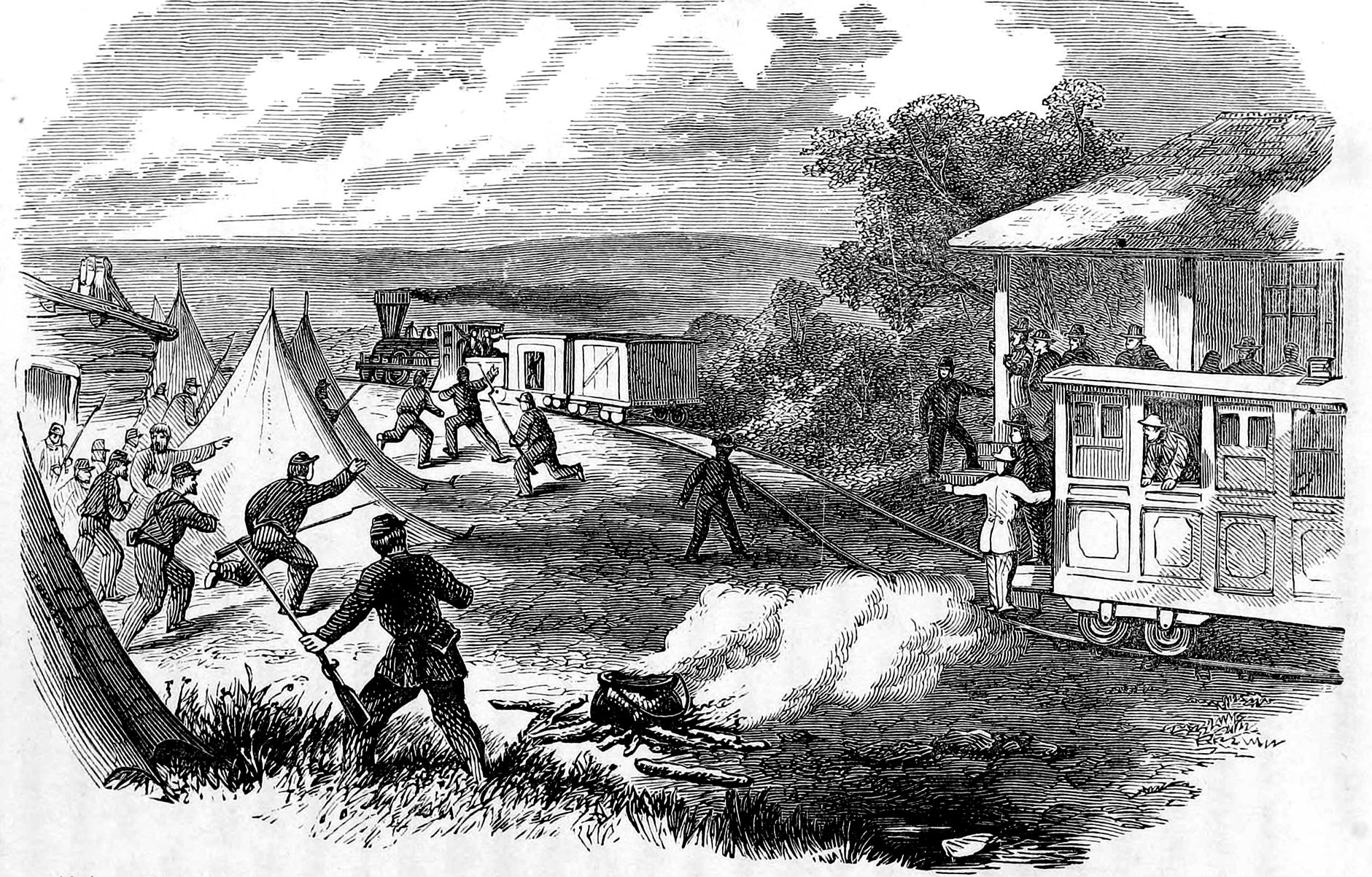

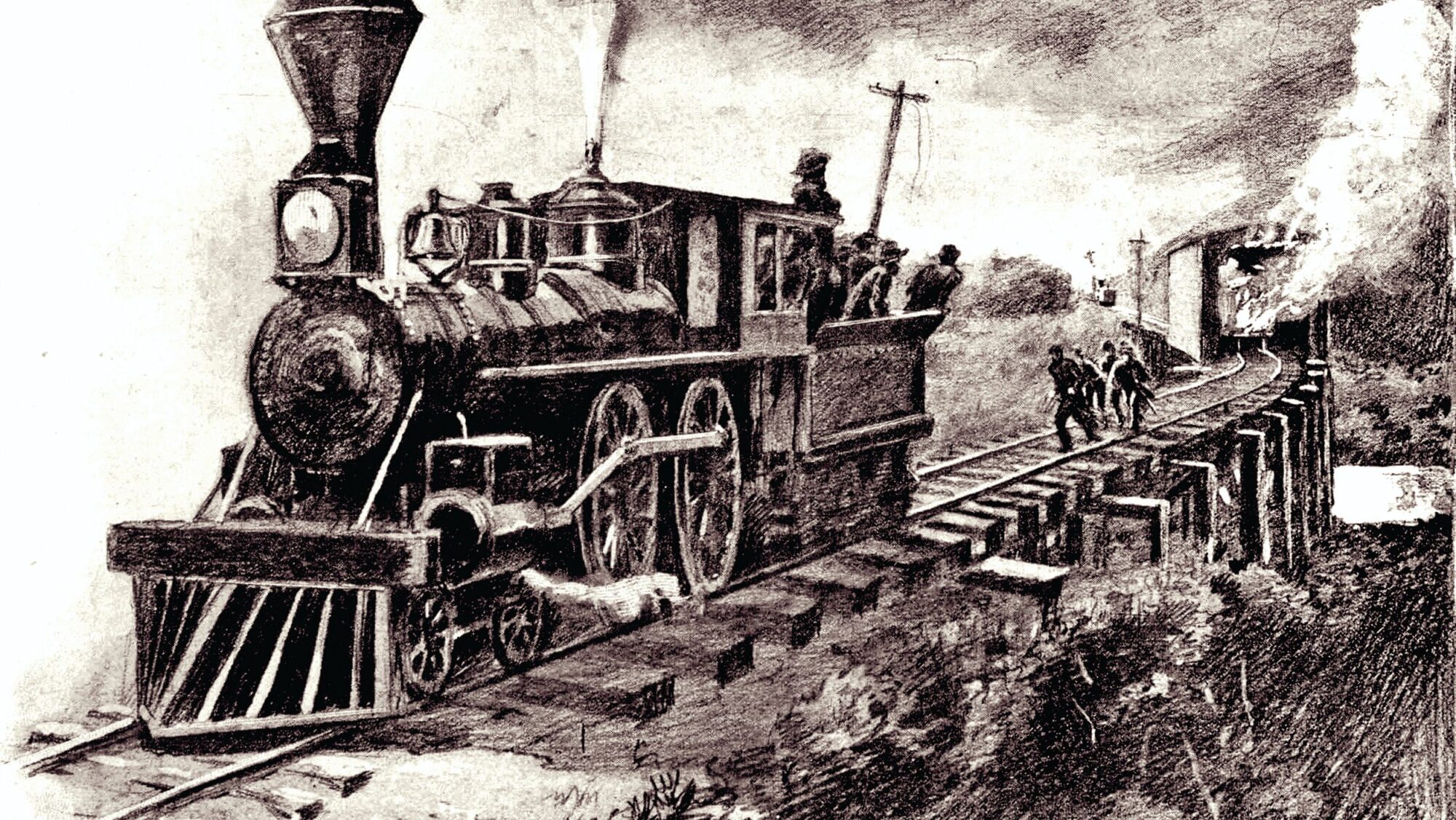

The raiders stole the locomotive General, along with three box cars and headed north as planned. They had chosen Big Shanty because it had no telegraph to warn forces up the line. However, they hadn’t counted on the determination of engineer William Fuller and two of his crew, Jeff Cain, and Anthony Murphy. They ran after the General, then followed with a rail pushcart, before commandeering three successive locomotives—Yonah, William R. Smith, the Texas. Andrews and his men cut some telegraph wires, though in Dalton, they were a minute late and a warning went up the line—though they didn’t know it, they would have been captured in Chattanooga. They tried to destroy the tracks, but only managed to pull up some sleepers, which they either burned or threw on the rails to delay their pursuers, who were growing in number and speed.

At Kingston, the General was delayed an hour on a sidetrack waiting for several southbound freight trains. There would be delays at other stations and soon, the raiders could hear what was now the Texas, gaining on them. They tried to slow it by releasing two of the General’s boxcars, but Fuller slowed enough to safely catch the cars. They set the last boxcar on fire on the bridge over the Oostanaula River, but wet from the rain, it didn’t ignite the structure or slow their pursuers. Fuller was so close now that they couldn’t stop for wood, water, or to try to damage more track. The wood-burning General ran out of fuel just north of Ringgold, Georgia, less than 20 miles from Chattanooga. Andrews and his men, who scattered into the wilderness, were all captured within two weeks.

Parrott, along with Private Samuel Roberston, were captured the same day they left the train and taken to Ringgold, according to Pittinger. Parrott, being the youngest and presumably the easiest to break, was stripped naked and held over a rock by four Confederates while two others pointed revolvers at him threatening to shoot him if he resisted. A lieutenant whipped him with a rawhide, pausing three times to lift him up and ask if he was ready to confess. Parrott continued to refuse and the lashing was discontinued after more than 100 strokes. He was offered no medical attention and remained scarred for life.

The captured “engine thieves” were then taken by rail to Marietta where, Pittenger wrote in Capturing a Locomotive, a “heavy guard of six hundred cadets was placed around us for the purpose of keeping down the mob.” A company of Confederate soldiers had left Big Shanty to lynch them, “but were overtaken by their officers when about half-way to Marietta and dissuaded from so rash an act, the officers arguing that we were soldiers, and it would not do for them to thus violate the rules of war, and also assuring them that we would be properly dealt with, and, in due time, executed. They thus succeeded in turning them back to camp.” It was there they discovered that Porter and Hawkins had also been captured.

The raiders were soon taken to Chattanooga where, after the capture of Wilson and Wood, all 22 of them were placed in “the hole,” a 13-foot square pit accessible only by a trap door in the floor. Near the end of May, Pittenger and 11 of the men were sent to Knoxville for trial. A week after their departure, Andrews was sentenced to death in Chattanooga. Both he and Private John Wollam managed to escape from the prison, though both were caught. After his escape, Andrews was shackled and a scaffold was erected for his hanging. Fear of an advance on the city by Mitchel from Huntsville caused them to move the hanging to Atlanta.

Pittenger and his group would later read of the June 7 execution of Andrews in Knoxville newspapers. Mitchel did send Brig. Gen. James Negley with a small division on an expedition to Chattanooga that bombarded the city on June 7-8. That action, coupled with Brig. Gen. George W. Morgan’s capture of the Cumberland Gap that same month, prompted the relocation of the rest of the raiders to Atlanta, but not before seven of them had been tried, convicted and sentenced to death. When Wollman was recaptured in late June, he was taken directly to Atlanta.

After a little more than a week in Atlanta, the seven raiders sentenced to death in Knoxville—Sgt. Maj. Marion A. Ross, Sgt. John M. Scott, Sgt. Samuel Slavens, Priv. Samuel Robertson, Priv. Charles P. Shadrach, Priv. George D. Wilson, civilian William Campbell—were hanged on June 18, 1862. They were buried in an unmarked grave, then moved to the Chattanooga National Cemetery in 1866,

In Atlanta the prisoners read newspapers discarded by the guards, then smuggled to them by African-American servants. About the raid, the Commonwealth (1861-1862) wrote that it was “either one of the most daring robberies or maddest pranks that has ever fallen under our notice… this was certainly one of the most bold and reckless feats of the war, and had they succeeded in their designs would have been of incalculable injury to our cause.” In the South, it was Fuller and the railroad employees who were the heroes. The Andrews Raiders were “Lincoln’s Spies, Thieves, and Bridge-Burners,” according to The Augusta Chronicle. The Southern Confederacy of Atlanta (1859-1865) called it “the deepest laid scheme and on the grandest scale that ever emanated from the brains of any number of Yankees combined.”

Two letters from the Confederate Secretary of War to Colonel George W. Lee, provost-marshal of Atlanta, forced the remaining Andrews men to take action. The first letter asked why all of the raiders had not been hanged and the second ordered that it be done. On October 16 the men attempted an escape, overpowering the jailer and some of the guards. A few never made it out of the prison yard. Some, like Parrott and Reddick, were recaptured inside the prison walls and by the following day, six were back in their cells. Eight had managed to escape, eventually making their way to Union lines—Priv. Wilson W. Brown, Corp. Daniel A. Dorsey, Corp. Martin J. Hawkins, Priv. William J. Knight, Priv. John R. Porter, Priv. John Wollman, and Priv. Mark Wood.

The six remaining raiders—Priv. William Bensinger, Priv. Robert Buffum, Sgt. Elihu H. Mason, Priv. Jacob Parrott, Corp. William Pittenger, and Corp. William H.H. Reddick— were sent to Richmond, arriving on December 7, 1862. According to Pittinger, the letter that sent them there read in part that “ten disloyal Tennesseeans, four prisoners of war, and six engine-thieves, were hereby forwarded to Richmond by order of Gen. Beauregard.”

The six would spend the next three months in Castle Thunder—a converted tobacco warehouse used primarily for civilian prisoners, including captured Union spies, political prisoners and those charged with treason. Many of its inmates were sentenced to death and the guards there had a reputation for brutality.

By January 1863, dysentery and smallpox were prevalent as the 1,400-capacity prison now housed 3,000 men and women. The raiders spent December and January in a stall some 8 feet x 16 feet. They had no fire and the barred windows were open to the air. Pittenger recalled that, “As the darkness and coldness of night drew on, we were compelled to pace the floor, trying to keep warm; and when sleep became a necessity, we would pile down in a huddle, as pigs sometimes do, and spread over us the thin protection of our two bits of carpet. Thus we would lie until too cold to remain longer and then arise and resume our walk.”

In February, the raiders petitioned to be moved to a room on the lower floor with a wood stove and 100 other other Union soldiers waiting to be exchanged. Finally, they boarded the truce-boat on the James River on March 18, 1863. They continued upriver to Washington, where they gave depositions and then received the first Congressional Medals of Honor. The first of the six was presented to Parrott. The men were also given $100, promised back pay and compensation for the weapons taken from them. They were all promoted to first lieutenant and given furlough to visit their homes.

The U.S. military’s highest award for valor had just been authorized by Congress in December of 1861, initially for the Department of the Navy. A couple of months later, it was authorized for the U.S. Army as well. The medal is now bestowed on any member of the armed forces who has “performed a personal act of valor above and beyond the call of duty in action against an enemy force.” More than 3,500 Medals of Honor have been awarded since 1863, with Union veterans of the Civil War receiving 1,522. Among America’s other conflicts, veterans of World War I received 126 and 471 were awarded for World War II. To date there have been 19 individuals who have been honored twice.

The Great Locomotive Chase caught the public imagination at the time, especially in the northern states where the “train thieves” were hailed as heroes. Over the last century and a half, there have been reenactments, festivals (Adairsville, Georgia), many books, songs and a couple of films—Buster Keaton’s silent The General (1926) and Disney’s The Great Locomotive Chase (1956) starring Fess Parker who had gained fame as Davy Crockett in a Disney miniseries of the same name.

But the raid had no military effect. The cut telegraph lines and pried rails were quickly repaired and the heavy rain prevented any bridges from catching fire. General Mitchel’s forces did capture Huntsville, Alabama, on April 11 but did not move on to Chattanooga. It would take until November 25, 1863, for Union forces under General Grant to take the city, setting the stage for Sherman’s infamous “March to the Sea.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments