By Marc G. De Santis

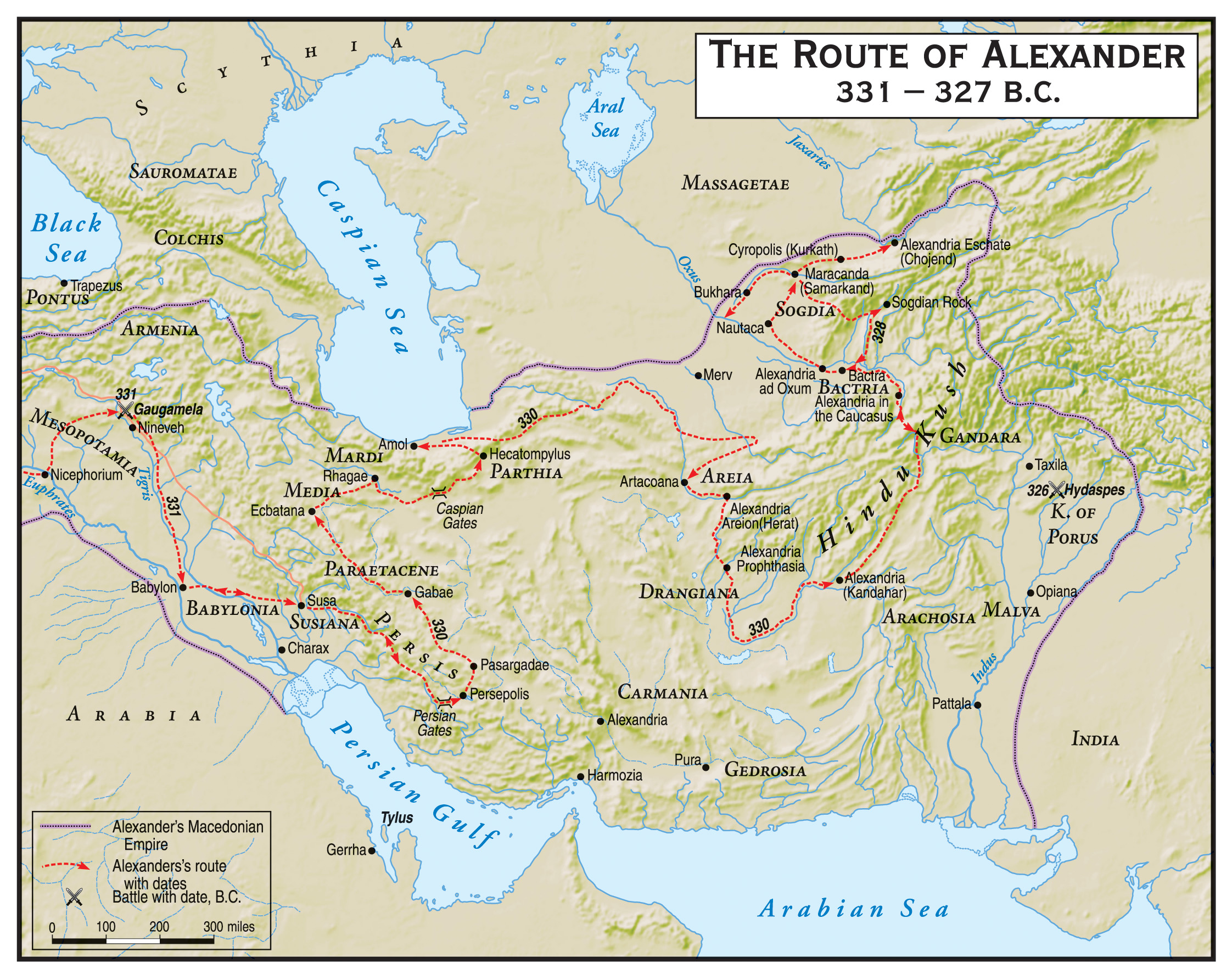

In the autumn of 331 bc, Alexander the Great won a decisive victory over the Great King Darius III of Persia at the Battle of Gaugamela. The battle was the conclusion of his epic campaign to avenge the Persian invasion of Greece 150 years before. Gaugamela was the last of series of great battles, including Granicus in 334 and Issus in 333, by which the armies of the Persians were smashed to pieces. His victory left him the master of the western and central portions of the old Persian Empire, but Alexander was not satisfied with the enormous territories he had won. The eastern territories of the empire were not under his control and several of the most distant provinces, or satrapies, traditionally contributed some of the finest fighting men to the Persian army. As long as these areas lay outside of Alexander’s grasp, they might yet prove a threat to the consolidation of the empire under his rule. Further, Alexander styled himself to be not merely the King of Persia, but something greater, Lord of Asia. He could not abide that any lands of the former empire should lie outside his grasp. The rugged Northeast Frontier, particularly the satrapies of Bactria and Sogdia, had to be subjugated. That would not to be easy. The terrain, embracing parts of modern Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan, was mountainous and scarred by deserts. The story of Alexander the Great in Afghanistan would turn out to be one of hostile natives waging a war of national resistance, threatening his dream of conquest and world empire.

Alexander Possessed Military Genius, and Latent Flaws

Alexander’s campaigns in the Northeast Frontier displayed, to an even greater extent than his set-piece battles against Darius, the flexible military genius that he possessed. He had won his great battles against the Persians through the masterful use of an army that efficiently combined heavy cavalry, heavy infantry, and light forces. Alexander was ever ready to experiment and take risks, to strike boldly before his opponents could react, and this dash time and again gave him an edge over his enemies.

The fighting in the northeast, however, would be a long and bloody war of guerrilla actions and sieges, and Alexander would spend the better part of three exhausting years putting down the recalcitrant peoples of the distant satrapies of the region. In this time too, the latent flaws in Alexander’s character became more apparent, and drunkenness and murder came to characterize the young king just as much as his earlier chivalry and clemency to the defeated once had.

It was in the cold mountains and parched deserts of the northeast that Alexander began his moral and physical dissolution. The primary sources for this period of Alexander’s career are Arrian and Curtius, who both wrote many centuries afterward. Together they paint a picture of a young king undone by his remarkable good fortune. When frustrated, as he would be on the Northeast Frontier, Alexander responded with a fearful brutality that belied his otherwise noble image. At the end of his trials in the north, many of Alexander’s closest comrades and officers, as well as native peoples, would lie dead, victims of his rage.

In the aftermath of Gaugamela, Persepolis, capital of the empire, was looted and burned. This left the defeated Persians in no doubt as to who was in charge. The spoils of conquest were many, including a massive take of Persian treasure—the astonishing sum of 120,000 talents. Alexander, however, was interested in more than money. He was focused on capturing the still-at-large Darius. The Persian king had fled the disastrous field of Gaugamela, making good his escape when Alexander was forced to break off his pursuit and ride to the aid of his embattled left wing. The Macedonian conqueror thereafter spared no effort to capture Darius.

To have Darius as a hostage would have brought untold benefits to Alexander, who could have used his royal captive as a means of legitimizing his rule over the empire, perhaps by having Darius abdicate and name Alexander as successor. In the next year he led his men on a desperate chase and finally caught up with Darius in July of 330. The unfortunate Persian monarch, however, had been murdered on the orders of one of his officers and kinsman, Bessus, and expired near the city of Hecatompylus before Alexander could reach him. Alexander had Darius’s body sent to Persepolis for a royal funeral and mourned his passing.

During this period Alexander also reorganized his army. With the battles against Persia won, he considered the Greeks’ great crusade against the Persians—united under Macedonian leadership by the League of Corinth—to be over. He dismissed from the army the allied Greek contingents as well as the fine Thessalian cavalry who had served him so well. Every soldier was paid in full and Alexander contributed a gratuity of 2,000 talents. Each horseman received a bounty of one talent and each footsoldier a bounty of one-sixth talent. Any who wished to enroll in the army as a mercenary might do so and many took up the offer, receiving a very generous bonus of three talents. Those who wished to leave were escorted back to Greece. The subtle effect of this largesse and reorganization was to bind Alexander’s troops more closely to him, dependent upon him for pay, thus weakening the hold of the old guard of Macedonian officers who had served under his father, Philip.

Alexander Desired that the Old Order Would Serve Him

In eastern Iran Alexander fought several campaigns aimed at quelling local resistance to his rule. In the north, he tracked down the remnants of Darius’s army under Bessus and received the submission of several cities and former Persian satraps. Among those who pledged their loyalty to Alexander were Satibarzanes, satrap of Areia in the northeast, and Barsaentes, satrap of Drangiana and one of the murderers of Darius. Despite Barsaentes’ regicide, Alexander accepted his submission and confirmed him in his office. Additionally, Alexander sent a small mounted force of 40 javelineers along with Satibarzanes back to Areia. Alexander was not interested in completely overthrowing the old order, but rather in making it serve him. His policy of clemency toward Darius’s old satraps thus was calculated to preserve the stability of the empire.

In the meantime, Bessus, the satrap of Bactria, had declared himself the new Great King, wearing the royal tiara and taking the regal name of Artaxerxes IV. Bessus was of the royal Achaemenid family and, being of royal blood, could serve as a focus of loyalty for Persians chafing under Macedonian domination. He had assembled an army of Persians and Bactrians and was awaiting the arrival of a force of Scythian allies. Bessus’s adoption of the kingship was a challenge to Alexander, who could not let such an action go unpunished. He immediately made plans to hunt down the Bactrian satrap.

The initial stage of the march to Bactria would be through uncultivated land that could supply little in the way of provisions, and so Alexander had all excess baggage, including his own, burned in preparation for the campaign against Bessus. He set out for Bactra (Balkh), the capital of Bactria, along the Persian royal road. While on the way, word arrived that Satibarzanes had rebelled and slain the javelineers and their commanding officer. The renegade satrap had called for a mass rising in Areia in favor of Bessus and was massing his troops at Artacoana (near Herat).

The situation was dangerous. This was the first instance of open rebellion to Alexander’s new order. Until this point, the overwhelming might of the Macedonian army had awed most of the peoples of the Persian Empire into submission. Macedonian overlordship had been accepted, and thus Alexander’s conquests had not required very large garrisons to maintain order. As a result, most of the garrisons were very small and would be vulnerable to a general uprising by the recently conquered natives. It was imperative that Alexander move quickly to contain Satibarzanes’ revolt before it could spread to other currently quiescent satrapies.

A Ramp Made of Fallen Trees Caught Fire and Spread to the Summit

As was typical for Alexander, he seized the initiative and with a body of picked troops marched the 70 miles to Artacoana in just two days. Satibarzanes took flight with 2,000 cavalry at Alexander’s approach and joined Bessus in Bactria. Most of the Areian people whom Satibarzanes had called to his banner were left to fend for themselves in the natural mountain stronghold of Kalat-i-Nadiri. This was a large, flat-topped mountain with a sheer western face and a more gently sloping eastern side. On the top was a grassy plain fed by a sizable spring. The stronghold was filled with all those Areians unfit for war and garrisoned by some 13,000 troops. Alexander had left nearly his entire army under Craterus to besiege the place while he moved on to Artacoana.

The Macedonians assaulted the steep western side of the mountain fortress and made some progress, but were thwarted by its impassible precipices and could go no farther. Impregnable, Kalat-i-Nadiri resisted Alexander’s siege techniques in a way that no other fortified place had before or would later. The Macedonians attempted to build a ramp of felled trees to the top of the mountain’s western end. This ramp caught fire, however, or was set ablaze, and the flames were fanned by fierce winds from the northwest that blow from June to September (it was then August). The fire spread to the summit and killed the Areians who had taken refuge there.

For the next month, Alexander conducted a campaign to pacify Areia. Using the royal road as a base, Alexander divided his army into several columns and rooted out the Areian rebels. The leaders of the rebellion were put to death and the last holdout—Artacoana—surrendered as the Macedonian siege towers trundled up to its walls. As a safeguard against further trouble in his rear, Alexander established a military garrison city near Artacoana—Alexandria Areion, or Alexandria of the Areians. There he made provisions for the education and training of selected boys, to inculcate in them Greek culture and ready them for future military service in the army. Additionally, Alexander installed a Persian named Arsaces as satrap in place of Satibarzanes.

Alexander then moved south to deal with the other regicide, Barsaentes, satrap of Drangiana. There could be no accommodation with one of Darius’s murderers in the wake of the rebellions of Bessus and Satibarzanes. Alexander could not afford to leave an enemy at his back. Barsaentes too had fled to India at the approach of the Macedonian army and the Macedonians occupied the capital of Drangiana, Phrada, for nine days in October 330.

While at Phrada there occurred an episode that throws great light onto the character of Alexander at this stage of his career and the shrewd and murderous political mind that the king possessed. A plot to take Alexander’s life was uncovered. One of the conspirators was a lowly Macedonian soldier named Dymnus who bragged about the plot against Alexander to his homosexual boy-lover, Nicomachus. Under an oath of secrecy, Dymnus revealed to the boy the names of the plotters who were conspiring to kill Alexander. The boy then told his brother, Cebalinus, who immediately went to the king’s tent with the news. As he had no authority to enter, the youth waited outside and approached Philotas, son of Parmenio, one of Alexander’s senior generals who had also served under Philip II for many years.

Philotas was a friend of Alexander and a superb cavalry officer. He led the Companions, Alexander’s elite horse troops, with great skill and daring. But Philotas was also brash and blunt and offended many Macedonians with his talk. Not least among these was Alexander himself. According to one story, Philotas had claimed, while drunk, that he and his father Parmenio had been responsible for all of Alexander’s great achievements. Through such talk, Philotas struck a nerve in Alexander, whose relationship with Parmenio had long since begun to deteriorate.

“I Will Not Demean Myself by Stealing Victory Like a Thief”

The histories of Alexander contain a strong anti-Parmenio theme. At critical junctures in Alexander’s march into Asia, Parmenio’s counsels conflicted with the course ultimately adopted by Alexander. After the battle at Issus, for example, Alexander received a message from Darius offering him the western half of the empire and the hand of his daughter in marriage in exchange for peace. Parmenio, the cautious old soldier, probably worrying that Alexander’s luck could not last, advised Alexander to accept the offer. Alexander, in dramatic fashion, said, “I would, were I Parmenio; but since I am Alexander I shall send Darius a different answer.” Alexander then flatly refused Darius’s offer. In a later episode, Parmenio, rightly concerned by the awesome size of the Persian host at Gaugamela, advised Alexander to attack at night, when their chances would be more favorable. “I will not demean myself by stealing victory like a thief,” Alexander responded tartly.

The conflict between Alexander and Parmenio was, at root, generational. Parmenio was of the old guard of officers who had helped make the Macedonian army and kingdom a power in the Greek world. In their eyes, Alexander was an arrogant upstart, frightening because of his success. They served him loyally, as they had his father, but they could not control him. From Philotas’s bragging, there must have been an undercurrent that ascribed Macedonian success in battle not least to Parmenio’s careful generalship and Philotas’s own acumen.

Further, the elderly Parmenio enjoyed great popularity among the Macedonian rank and file. They knew him from their earliest days in the army. He was a steady man and had managed to preserve Alexander’s victory at Gaugamela by holding the beleaguered Macedonian left wing together until Alexander could come to the rescue. However, the continual reports in the ancient sources of disagreements between Alexander and Parmenio reflected deep divisions over policy.

In the early years, most of these divisions were tactical, but with the defeat of Darius, the disagreement was as much over vision as anything else. Parmenio, as we saw, would have been content with an empire of all the lands west of the Euphrates, as Darius had suggested after Issus. Alexander had gambled at Gaugamela for more and had won, but where would the fighting end? Must Alexander insist on conquering all of the lands once held by Darius, including the eastern satrapies? Parmenio had already been relegated to a post at Ecbatana in the province of Media, away from the main army. He was a hindrance to Alexander’s dream of world conquest and now that Persia was in Alexander’s hands, perhaps also superfluous.

Philotas Kept the Conspiracy Hidden From Alexander

Cebalinus now told Philotas what his brother Nicomachus had told him of the threat to Alexander’s life and implored him to report it to the king immediately. Philotas commended Cebalinus and went into the tent to speak with Alexander. He spoke with him on other matters, and never once mentioned Cebalinus’s warnings. Later that day Cebalinus saw Philotas again and asked him if he had told Alexander about the plot. Philotas claimed that Alexander had no time to speak with him and went on his way. The next day, Cebalinus again accosted Philotas and asked him to give the king his warning. Philotas told him that he was seeing to the matter, but once again did not tell Alexander of the conspiracy.

This runaround caused Cebalinus to suspect Philotas, so he sought another means to warn the king. He told a young nobleman named Metron, who was in charge of the armory, about the plot against Alexander. Metron hid Cebalinus in the armory while he went to tell Alexander. Upon hearing the news, Alexander sent guards to arrest Dymnus and went to the armory. Cebalinus told him the details of the conspiracy. After hearing the account, Alexander asked how long he had known of the plot. Hearing that it had been two days, Alexander had the poor youth put in irons, thinking that the delay meant that his loyalty was suspect. Cebalinus protested that he had gone to Philotas as soon as his brother told him of the plot. Alexander asked again if he had informed Philotas and insisted that he tell Alexander of the plot. Cebalinus again and again affirmed his account. With that, Alexander wept with his hands stretched to the heavens and bitterly complained that one who had been such a dear friend might repay him so.

While Cebalinus was being questioned, Dymnus heard of his summons to see the king. Suspecting the reason for this, he attempted to commit suicide. Before he could finish the job, the guards intervened and brought the mortally wounded Dymnus to Alexander. “Dymnus,” said Alexander, “what is the vicious crime I have plotted against you to justify your decision that Philotas deserves royal power more than I myself.” Dymnus, by this time incapable of speech, turned away from Alexander and died.

Philotas was now brought to Alexander’s tent. “Cebalinus deserved the supreme penalty,” began Alexander, “if for two days he covered up a plot that had been hatched against my life. But he shifts the guilt for his crime to Philotas by his claim that he passed the information on to him immediately. Because of your closer ties of friendship with me, such suppression of information on your part is all the more reprehensible, and it is my opinion that conduct such as this suits Cebalinus more than it does Philotas. You now have a judge who is on your side—if there is any way of clearing yourself of what should not have happened.”

Philotas showed not a trace of distress at this news. He answered that he had indeed been told of the plot by Cebalinus, but because the source of the report was Dymnus’s boy-lover, he thought it unreliable and feared that telling Alexander would make him a laughingstock. Dymnus’s death by his own hand showed now that there was some merit to the story and that he should not have suppressed it. Philotas hugged the king and begged him to consider his past service to him and not his current error.

Alexander gave Philotas his hand in reconciliation and declared that in his opinion Philotas’s wrong was in not taking the story seriously enough rather than in attempting to conceal it from him.

”Protect Yourself Against Enemies Within Our Ranks.”

Nevertheless, the next day Alexander had the boy Nicomachus brought before him, without Philotas in attendance, to tell his side of the story. Among those present was Craterus, a high-ranking officer who had commanded a taxis, or battalion, of the phalanx at Issus and Gaugamela and had long disliked Philotas on account of his boastfulness. Seeing a chance to destroy Philotas, he warned Alexander of Philotas’s continuing threat.

“You see,” said Craterus, “he will always be able to plot against you, but you will not always be able to pardon Philotas. And you have no reason to suppose that a man whose daring has been so great can be changed by a pardon: he knows that those who have exhausted someone’s clemency can expect no more in the future. But even supposing penitence or your generosity induced him to take no further action, I for my part am sure that his father Parmenio will not be happy at being indebted to you for his son’s life—he is the leader of a mighty army and because of his longstanding influence with your men holds a position of great authority not much inferior to yours. Some acts of kindness we resent. A man is ashamed to admit that he deserved execution; the alternative is to foster the impression that he has been dealt an injury rather than granted a reprieve. So you can be sure that you must fight for your life against the men in question. The enemies we are about to pursue [Bessus’s followers] are still numerous enough. Protect yourself against enemies within our ranks. Eliminate those and I fear nothing from the foreigner.”

The other officers present at the meeting agreed that Philotas was at the very least an accomplice to the plot, for even the lowest Macedonian, if loyal, would have gone straight to Alexander with news of the conspiracy. Philotas, though a close friend of Alexander, did not warn the king, therefore he must be guilty. They decided to question Philotas under torture to extract from him the names of the other accomplices in the plot. That night, guards were placed at all of the entrances to the camp to prevent anyone from stealing away to Ecbatana to tell Parmenio what was transpiring in Phrada. A detachment of three hundred guards marched into the city to arrest Philotas. Parmenio’s son was seized in his sleep and his head was covered. “Your Majesty,” he said as the guards placed him in irons, “the bitter hatred of my enemies has triumphed over your kindness.”

Alexander called a general assembly of 6,000 Macedonian soldiers. These troops would be the jury that decided Philotas’s guilt or innocence. Philotas was brought before the men, his arms tied behind him, a pitiful sight in the eyes of the soldiers who had known him as the leader of the Companion cavalry. The story of the plot and Philotas’s dereliction of duty was told and some Macedonians vented their resentment against Philotas’s highhanded ways. They had been thrown out of their billets in the city to make way for Philotas’s booty, they complained. Alexander dismissed the meeting before things could get too far out of hand.

Officers Were Sent to Extract a Confession from Philotas Through Torture

That evening at another meeting, it was decided that Philotas should suffer the traditional penalty for his crime—death by stoning. First, Alexander wanted Philotas to write a confession and some statement implicating Parmenio in the plot. Three of Alexander’s highest ranking officers—Craterus, his best friend Hephaestion, and Coenus, another taxis commander—were sent to extract these from Philotas by torture. By the next day they had gotten both out of Philotas, who during his session with his torturers asked, “Craterus, what do you want me to say?”

Philotas was brought before another assembly of the soldiery and was stoned to death, the punishment as prescribed by Macedonian law. With Philotas dead Alexander could not suffer the father to live. He sent a Companion officer, Polydamas, with Parmenio’s death warrant by racing camel through the desert to Ecbatana, to make certain that Polydamas arrived at Ecbatana before any word of Philotas’s death could reach the general. Polydamas delivered the warrant to Cleander, Parmenio’s second in command. Cleander informed his staff officers and together they put the old man to death. Parmenio was 70 years old.

In far-off Macedonia, Antipater, regent while Alexander was away in Asia, received word of Parmenio’s execution. “If Parmenio plotted against Alexander, who is to be trusted? If not, what is to be done?” he asked plaintively. The trial of Philotas and the murder of Parmenio signaled a new phase in Alexander’s moral decline. Even the highest ranking generals were vulnerable to Alexander’s murderous wrath if they opposed his will. This was the antithesis of the rough and ready, egalitarian kingship of the old Macedonia that Alexander’s father, Philip II, had represented. Philip’s old officers had been somewhat amused by their young king’s divine pretensions, whether as a descendant of Heracles or as a son of Zeus-Ammon, as he was proclaimed in Egypt. Alexander took his divine parentage very seriously. Now, it seemed, there was nothing amusing about it at all.

It was late 330 when Alexander continued his offensive against Bessus. To safeguard against future plots, he decided to divide command of the Companions between two officers, Cleitus the Black, who had saved his life with a cunning sword stroke at Granicus in 334, and his friend Hephaestion. He took a northeasterly route through the satrapy of Arachosia, in what is now eastern Afghanistan, a territory not yet brought under Macedonian control. Soon after he had set out for Arachosia, word arrived that there had been another revolt in Areia, abetted by Satibarzanes with his 2,000 cavalry. Alexander dispatched a force under two Companions, Erigyius of Mytilene and Caranus, to suppress the Areians. Old but still full of fight, Erigyius killed Satibarzanes in single combat in November 330 and the revolt failed soon afterward. Areia would be a security problem for many years and the satrap appointed to replace Satibarzanes, the Companion Stasanor, would not succeed in quelling local disturbances there until the winter of 327.

Alexander the Great in Afghanistan: Beginning His Offensive Against Bessus

During the final months of 330, Alexander campaigned in the eastern satrapies. From the satrapy of Drangiana he moved southward and rested his army for two months among the Ariaspians, known as the Euergetae, or Benefactors. They received this title because of their generosity in supplying the hungry soldiers of Cyrus the Great with thousands of wagonloads of grain two centuries earlier. They submitted to Alexander, who increased their territory and allowed them to keep their freedom. While he built up supplies for the push northward, Alexander was joined by the troops that had been under Parmenio’s command in Media. At some point he founded two new cities: Alexandria at modern Kandahar and Alexandropolis at Kalat-i-Ghilzai.

His army reinforced, Alexander began his offensive against Bessus in the spring of 329. The Macedonians crossing the Hindu Kush in early April suffered terribly from the cold. Frostbite and chronic fatigue caused by the low oxygen at high altitude exacted a heavy toll on the men. The army rested for several days in the Kabul Valley and Alexander founded a garrison city—Alexandria in the Caucasus—with some 7,000 older Macedonians and retiring soldiers. The rest of the army then marched through the Khawak Pass to the Surkhab River, whose line it followed toward Drapasaca (Kunduz). The full crossing is said to have been completed in just 17 days, a great achievement for a large army in such difficult terrain.

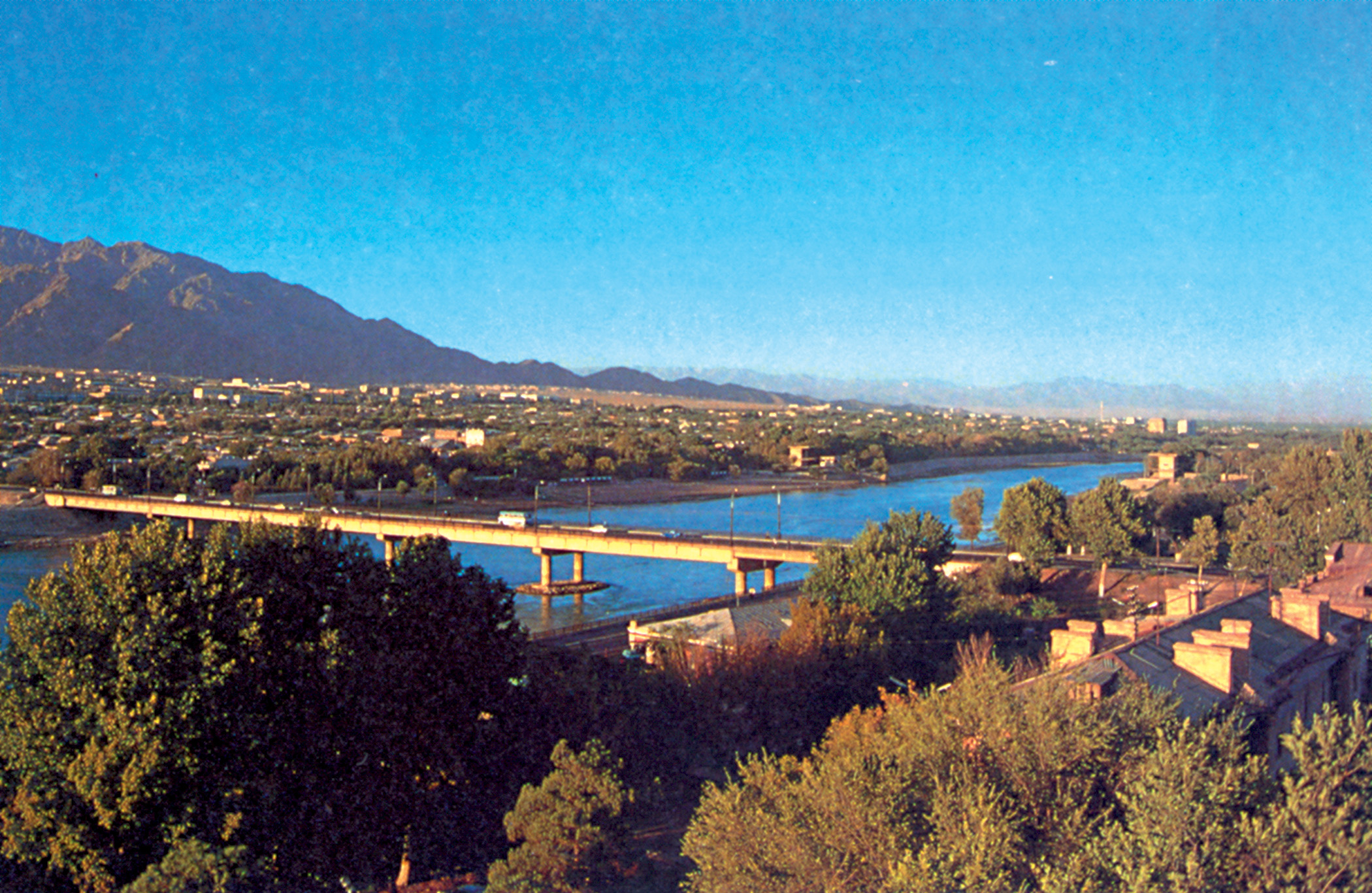

Alexander continued along the Kunduz river valley, a land that ordinarily was agriculturally very productive, but had been subjected to a scorched earth policy by Bessus as a means of slowing Alexander’s advance through lack of supplies. Bessus, in Bactria, was surprised and frightened by Alexander’s rapid moves against him and decided to make a stand against him in Sogdia, using the Oxus River (Amu Darya) as a barrier. He had 8,000 Bactrian troops with him, but when they saw that Alexander would invade their country instead of heading for the balmier climate of India, they deserted him. Bessus then began raising new troops among the Sogdians.

Despite Bessus’s scorched earth tactics, Alexander continued his advance in Bactria. The army marched to Aornus, where he left a garrison, and then to the capital of the satrapy, Bactra, modern Balkh, reaching it by June of 329. The geography of Bactria varies greatly. In some areas, particularly in the river valleys, trees are numerous and crops are grown in abundance. In other areas the land is desert and there is no vegetation to be found.

More Soldiers Lost to Dehydration and Over Drinking Than to Battle

During this time Alexander received word that Scythians from the steppelands of Central Asia were riding south to join Bessus. He appointed Artabazus, an elderly Persian aristocrat, to be satrap in Bactria and began his march to the Oxus. Alexander took a small group of lightly armed pathfinders with him, the main army following behind, and reached the river across from the Sogdian fortress of Termez. The route was some 46 miles through a hot and waterless desert in the middle of summer. The short distance belied the misery of the Macedonians as they followed their king through the parched land. Heatstroke felled some of the soldiers trudging along in the furnace-like weather. Their thirst was overwhelming. Alexander lit beacon fires for his men at night, or else they might have missed the camp in the dark.

Once the bulk of his troops reached the Oxus, many died from overdrinking—which blocked the windpipe because of the rapid gulping—in response to the severe dehydration their journey through the desert had caused. In fact, Alexander lost more soldiers to overdrinking than he had in any of his major battles. At this time, Alexander also dismissed from service the Thessalian cavalrymen who had stayed on after their national contingents were dismissed and some of the older Macedonian veterans, giving each a generous bounty and charging them to return home and beget children.

Crossing the Oxus posed more of a problem than Alexander had expected. The river was six furlongs wide and possessed a strong current. He had no boats to make a crossing and there were no trees in the vicinity with which to build a bridge. Alexander then tried the method he had used years before to cross the Danube. He ordered his men to fill their tents with whatever straw and other dry material could be found. Each soldier made himself a flotation device and in this fashion the soldiers swam across the river. Alexander’s army crossed the Oxus in five days.

In the wake of Alexander’s trek through the desert and his crossing, dissatisfaction among the Sogdian followers of Bessus boiled over. With his prestige already low because of the abandonment of Bactria, Bessus was arrested by a group of his own officers led by Spitamenes, a Sogdian baron. His plan was to offer up Bessus, the murderer of Darius, to Alexander and so convince him that the Sogdians were willing to accept Alexander’s suzerainty.

Spitamenes sent a message to Alexander saying that he would deliver Bessus to a Macedonian officer in charge of a small force of men. Alexander dispatched Lagus’s son Ptolemy (who would later found his own successor dynasty in Egypt) to take custody of Bessus. In four days of marching, Ptolemy reached Spitamenes’ camp. It was unoccupied; there had been a split of opinion between Spitamenes and others as to whether to give up Bessus and the occupants had pulled out. Nevertheless, Ptolemy continued and the following day came upon a village where a few soldiers had Bessus in their custody. After some negotiation, Bessus was turned over to Ptolemy. As was instructed by Alexander, Ptolemy placed Bessus bound and naked in a wooden collar and left him by the side of the road. Spitamenes had not wanted to be present at the handover, Arrian noting dryly that the actual betrayal of Bessus was too much for his conscience.

Alexander Possessed Great Depths of Cruelty

When Alexander approached Bessus, he was seething. “What bestial madness possessed you,” he began, “that you should dare to imprison and then murder a king from whom you received exemplary treatment? Yes, and you rewarded yourself for this treachery with the title of king which was not yours.” Bessus made no excuse for Darius’s murder, but answered lamely that he had done so to hand over the country to Alexander. This found no favor with Alexander, who put Bessus in the custody of Oxathres, a brother of Darius III and now one of Alexander’s bodyguards. Bessus was to be scourged and abused, his ears and nose cut off, but his execution was postponed until he could be killed at the very place where he had murdered Darius.

The humiliation of Bessus, although perhaps deserved, is an example of the depths of pitiless cruelty to which Alexander would sink if it served his purposes. Alexander may have been genuinely offended by Bessus’s betrayal of his king. Given the Philotas affair less than a year before and memories of the assassination of his own father, Alexander may very well have desired to make a brutal statement about the fate that awaited regicides and traitors. But like other examples of Alexander’s cruel streak, the punishment of Bessus was extravagant and done in a dark mood of cynical showmanship.

During this period, there occurred a shocking event and, if true (only Curtius mentions it), allows a chilling insight into Alexander’s character and his motivation for his war against the Persians. Along the march in pursuit of Bessus, the Macedonians came upon a city of people known as the Branchidae. Their ancestors had been relocated to the interior of Asia after Xerxes’ failed invasion of Greece in 480 bc. The priests and guardians of Apollo’s shrine at Didyma near Miletus in Asia Minor had turned over its treasures to Xerxes, who then burned the shrine. The Branchidae were said to have willingly accompanied the Great King back to Persia, where they were settled in a new home.

A century and a half had passed, but the Branchidae still spoke Greek, although the local language was gradually supplanting it. Among the Greeks, the treason of the Branchidae was infamous. Alexander called upon the Milesians present in his army, since the harm was done to them especially, to render a judgment on what should be done with the city. The soldiers from Miletus debated, but were unable to reach a decision. Finally, Alexander reached his own decision. The next day, he met with a delegation of the Branchidae and entered the city through the gate with some lightly armed troops. The battalions of the Macedonian phalanx, in the meanwhile, were deployed all around the walls. He gave a signal and the remorseless Macedonian war machine sprang into action. The walls were thrown down and the city sacked. The inhabitants were slain with the utmost savagery and even sacred groves were uprooted so that there should be nothing but a wasteland afterwards.

Alexander’s Father had Drowned 3,000 Mercenaries for Accepting Stolen Coin

The whole tale borders on the fantastic. Surely Alexander was not so cruel as to murder the people of an entire city because of the sins of their ancestors? But Alexander might well have thought very differently. The guilt of the priests of Apollo was inherited by their descendants. The treason of Thebes (which had sided with Persia) during the same invasions was used as a reason to level that city in 335. Alexander’s father, Philip II, in his role as champion of Apollo of Delphi, had drowned 3,000 mercenaries who accepted coin stolen from the god’s shrine. Alexander took on his role as avenger of the Greeks with a deadly seriousness. He had the Greek mercenaries in Persian service at the Battle of the Granicus slain to a man for their crime of fighting for the Great King. The massacre of the Branchidae was well in line with these earlier atrocities and excesses.

Alexander proceeded through Bactria and Sogdia, establishing small garrisons in seven cities along the Jaxartes (Syr Darya), the great river that marks the boundary between Sogdia and Scythia. The provinces were quiet and there was no resistance to the army’s passage. Indeed, the only casualties that the Macedonians suffered were from the terrain, with many of Alexander’s men lying dead in the cold Hindu Kush or the dry desert. Both Bactria and Sogdia (usually referred to by the Macedonians collectively as Bactria) were remote, albeit productive, lands and there was no objection on the part of the natives to Alexander’s assumption of power. To them Alexander was just another Persian ruler and they most fervently hoped that life would continue as it always had once the Macedonians had passed by them.

Interestingly, it was to be Alexander’s policy of founding cities wherever he went, which is usually regarded as one of his positive traits, that would cause the previously peaceful Bactrians and Sogdians to rise in revolt. The spark that would light the flame of war in the Northeast Frontier was the foundation of Alexandria Eschate, or Alexandria the Furthest (modern Chojend) on the Jaxartes River. It was a large city with long walls, but what distressed the natives was the character of the population Alexander settled there. It was the first permanent city built by the king in the region. All the earlier settlements had been small garrisons. Alexandria Eschate, on the other hand, was more like a fortress, with a large Macedonian military contingent as its principal element. Alexander’s purpose in founding the city was to have it serve as a bastion against Scythian penetrations of Sogdia south of the Jaxartes.

This was to Alexander a seemingly sensible goal, but one that caused the Sogdians great concern. The Sogdians and the Scythians were considered to be related peoples of similar ethnic origins. The border between Sogdia and Scythia, the vast area to the north of the Jaxartes, was not so much a boundary as a frontier in the truest sense. It was a large and fluid arena that nomads and pastoralists crossed to engage in trade. Alexandria Eschate would disrupt that interaction and thus the way of life for many of the natives of Sogdia.

As a consequence, the Sogdians began to attack the Macedonians, who had heretofore been enjoying a relatively peaceful march through the satrapy. A party of Macedonian troops was ambushed while collecting supplies and Alexander led a punitive expedition against them during which he was wounded. Soon thereafter the cities along the Jaxartes rose in revolt and slaughtered their garrisons. What followed was to be more than two years of bloody war in Sogdia and Bactria, quite unlike the glorious battles with Darius in the west.

The Stress of War Began to Take its Toll On Alexander

The ancient writers give little detail about the nature of the fighting in these years, but it is not too difficult to imagine. Ruthless search-and-destroy missions displaced thousands of villagers; there were midnight raids with fire and sword; townspeople were uprooted and resettled in new, easier-to-control locations; and everywhere the inhabitants of small fortified places made desperate last stands against the enemy. Glory was in short supply in the brutal campaigns fought across the frontier during these years.

Seven cities were assaulted and overcome. The chief city, Cyropolis (Kurkath), resisted the Macedonians with special vigor. Alexander wanted to spare this city because it had been founded many years before by the Persian conqueror Cyrus the Great, whom Alexander greatly admired. But he was so angered by the continued resistance that upon its capture he decided to sack the city. Tunneling operations beneath the walls caused a huge collapse and the city was destroyed. Alexander was wounded severely in the neck by a stone while besieging another city. Its inhabitants were slaughtered.

The stress of war took its toll on Alexander. In addition to the accumulation of serious wounds, he began to drink all the more heavily, not merely in a social fashion, but to the point of undignified drunkenness. He had given up consulting seers and prophets after Gaugamela, but also began to indulge his superstitions and listened to the portents of his court seer, Aristander, who divined the future through the study of animal entrails.

One of Alexander’s most difficult tests came when he faced the Scythians. A nomadic nation of fearsome mounted warriors, they lived on the far side of the Jaxartes. The king of the Scythians, like the Sogdians, was also worried by Alexandria Eschate and sent a large force of cavalry to destroy the settlement. The Scythians were a ferocious people and their kings had a habit of making drinking cups out of the gilted skulls of their enemies. They were not to be trifled with, but Alexander could not leave them alone on his worrisome Northern Frontier. In his camp tent, Alexander conferred with his officers, speaking in a hoarse whisper because of his wound from the fighting at Cyropolis, “This crisis favors the enemy more than it does me. If we ignore the Scythians then we will have no respect from the rebels when we return to them. But suppose we cross the Jaxartes and with a bloody slaughter of the Scythians demonstrate that we are universally invincible? Mind you, the slightest hesitation on our part and the Scythians will be on our backs.”

“I Fear That You May Not be Equal to the Situation Your Face.”

His men tried to dissuade the king from taking the offensive and Erigyius spoke of the unfavorable omens that Aristander the seer had divined for the operation. Alexander was livid. Aristander had told Erigyius of his divinations when he had entered Alexander’s tent. Such matters were to be for Alexander alone and embarrassed him further for his seeming reliance upon such superstition. The king said to Aristander, “When I instructed you to offer sacrifice, I did so not as your king but as a private citizen. Why did you divulge the portents to someone other than myself? From your disclosures Erigyius knows of my confidential and private affairs, and I am convinced he interprets them according to his own fear. But I am instructing you to tell me what you learned from the entrails, so you cannot later deny having told me what you say now.”

Aristander had been given a chance to save himself. His fear kept him from speaking for a moment and then, finally, he said, “I predicted a perilous situation ahead of us that would involve hard, but not fruitless effort, and my concern is prompted less by my professional knowledge than by my devotion to you. I see that you are in poor health and I know how much depends on you alone. I fear that you may not be equal to the situation your face.” Aristander collected himself and left the tent, but returned soon afterward. Alexander and his officers were discussing ways to cross the Jaxartes. Aristander had performed another inspection of a sacrifice and he declared, rather wisely, that in regard to the coming operation, he had never before seen more favorable entrails.

An embassy now arrived from the Scythians on the far bank. They said to Alexander: “Had the gods willed that your stature should match your greed the world could not hold you. Even as it is you covet things beyond your reach. Now you are stretching out your greedy, insatiable hands towards our flocks. Why do you need more riches? You are the first man to have created hunger by having too much—so that the more you have the keener your desire for what you do not have. Just cross the Jaxartes and you will discover the extent of Scythian territory—but you’ll never catch the Scythians. With our meager belongings we shall outrun your army with its cargo of booty from so many nations. Then, when you think that we are far away, you will see us inside your camp. We pursue and retreat with equal speed.”

Alexander concealed his annoyance and answered them, saying that he wished to avoid a reckless attack on the Scythians and dismissed the embassy. But the king had no intention of allowing the insolent barbarians any peace. He put his troops on rafts and skins he had had prepared for a crossing. The Scythians were waiting for him on the other side of the river, jeering at the Macedonians. On some of the rafts he mounted large oxybeles, giant crossbow artillery, along with slingers, to cover the movement of his troops to the far bank. Men with shields protected the oarsmen as they rowed across. Soon the missiles from the rafts cleared a strip of land for the Macedonians. They came ashore, their shields riddled with Scythian arrows, and pushed the enemy back.

Almost 1,000 Scythians Dead, 150 Captured

Alexander cleverly baited a trap for the Scythians. Knowing that the Scythians would encircle any force he sent against them, he allowed a small group of Macedonians to press forward. The Scythian horse archers promptly used their favorite tactic, circling around and showering them with arrows, never allowing the Macedonians to come to grips with them. Alexander sent two columns of cavalry along with his archers and Agrianian javelineers against the Scythian flanks. Alexander gave the rest of the cavalry and the mounted javelineers the order to charge and the encircling movement of the enemy was stopped cold. It was the Scythians who were now practically encircled. They broke and fled the field, leaving behind a thousand dead and 150 captured.

This victory reaped Alexander great dividends. The Scythian king soon apologized to Alexander and other Scythian tribes submitted to him. But bad news soon arrived from Maracanda, where Alexander had left a small garrison. While Alexander had been busy with the Scythians, Spitamenes had besieged the Macedonian garrison. Alexander dispatched a rather small expeditionary force of 60 Companion cavalry, 1,200 mercenary infantry, and 800 mercenary cavalry under Pharnuches to relieve the troops. This force successfully raised the siege, but came to grief while following after the elusive Spitamenes. Lured into a pursuit, they were cut to pieces by the deadly archery of Spitamenes’ Scythian cavalry. The endangered Macedonians sought the protection of a small island in the middle of the Polytimetus (Zeravshan) River. In such circumstances, the cavalry must act as a protective screen for the slower moving infantry. Here, however, the cavalry commander neglected his duty and tried to get his own men across the river first. The result was a rout. The infantry sought the safety of the river in disorder and were felled by the enemy archers. Only 300 infantry and 40 mounted troopers survived the disaster.

Alexander was shocked by the reports of the defeat and threatened to put to death any of the survivors who spoke of it. He assembled another force for a punitive expedition comprising half the Companions, the Macedonian archers, and the Agrianian javelineers and marched the 160 miles to Maracanda in just four days. By the time Alexander arrived at the scene, Spitamenes had fled. He had a mound built over the bones of his fallen soldiers and made sacrifices in their honor. On his return march he slaughtered any of the natives that he came across because, it had been reported, some had joined the attack on the Macedonians. Alexander then spent the rest of the winter of 328 at Bactra. He had made little headway against the uprising. Spitamenes was still on the loose—his hit-and-run tactics proving to be very effective—the frontier was in flames, and there seemed to be no end in sight.

A Furious Alexander was Determined to Find a Way to Capture the Rock

For the campaign of 328, Alexander left four taxeis of the phalanx behind to control Bactria and divided the remainder of his army into five flying columns, which moved north through a river valley in the Pamirs, destroying everything in their path. The Sogdian barons were rooted out of their forts and their fields burned. Not all of these mountain fortresses succumbed easily. In the summer, Alexander laid siege to the stronghold known as the Sogdian Rock. This was one of the strongest fortresses in Sogdia, a mountain fastness with sheer sides and well-supplied to withstand a long siege. Thousands of Sogdians under Ariamazes, a local baron, manned the fortress. Alexander at first wished to negotiate a deal with this seemingly impregnable place, but the Sogdians laughed at him. Ariamazes told Alexander to find soldiers with wings to take the Rock for him. Alexander was furious at his insolence and determined to find a way to capture the Rock.

The king put out a call for the best climbers in the army. The Macedonians were a tough people used to living in hilly country and some 300 men of great agility were found. He promised 10 talents to the first to reach the top of the Rock. The soldiers used iron pins and ropes to climb the face of the mountain and spent an entire day making their ascent. Slowly they made their way to the top of the mountain and signaled their success to Alexander. When Ariamazes saw the Macedonians on the Rock, he was so shocked and terrified that he surrendered, unaware of just how small the Macedonian numbers really were. He and 30 of his chieftains gave themselves up to Alexander. The king was in a foul, merciless mood because of Ariamazes’ arrogance. He ordered him and his noblemen whipped and crucified at the foot of the Rock. The rest of the inhabitants were enslaved and given as gifts to the newly founded cities in Sogdia, and the Rock was put in the charge of Artabazus. Alexander was now making progress.

After this successful siege, Alexander rested the army at Maracanda. He appointed Cleitus the Black to be satrap of Bactria. Artabazus had requested retirement on account of his age and the king made Cleitus his new governor of that province, which comprised both Bactria proper and Sogdia. Cleitus had saved Alexander’s life at the Granicus several years before and his sister, Lanice, had been Alexander’s nurse.

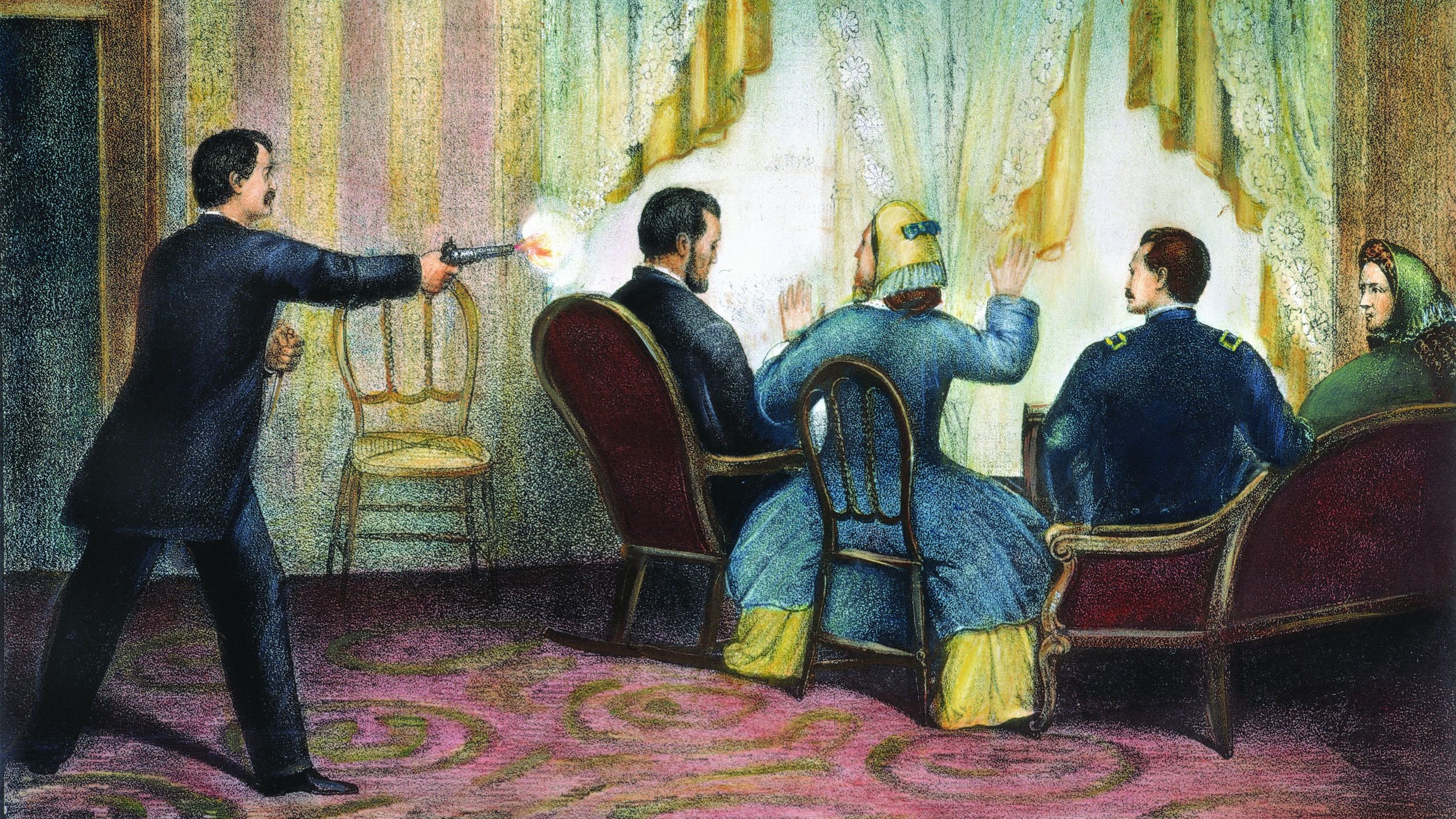

Soon afterward, Cleitus was invited to one of the raucous banquets that the hard-drinking Alexander held more and more often as the Asia campaigns wore on. As usual, Alexander was drinking heavily and droned on about his achievements to the annoyance of many present. But when Alexander began to demean his father Philip’s record, taking credit for the Macedonian victory over the Greeks at Chaeronea in 338, the older Macedonian officers were incensed. They had served under Philip and still cherished his memory. Many had been present at Chaeronea and would have had their own ideas about who had been the victor there.

Cleitus was one of these men. He too had been drinking and he recited a passage of Euripides’ play Andromache. The Greeks, he said, had adopted a bad practice in inscribing their trophies only with the names of their kings, thus allowing the kings to take credit for things won with the blood of others. Alexander took notice as Cleitus continued talking in a loud voice to be certain that Alexander could hear him. He spoke of Philip’s wars in Greece and his achievements and ranked them higher than any that had been conducted in Asia. Alexander was furious at Cleitus’s words, but was able to control his anger. Yet Cleitus was not finished.

A True Son of Zeus?

Cleitus defended Parmenio, incensing Alexander, and expressed his unhappiness with his new command. “If someone has to die for you, then Cleitus comes first. But when you come to judge the spoils of victory, the major share goes to those who pour the most insolent insults on your father’s memory. You assign to me the province that has often rebelled and, so far from being pacified, cannot even be reduced to subjection. I am being sent against wild animals with bloodthirsty natures. But my own circumstances I pass over. You express contempt for Philip’s men, but you are forgetting that, if old Attarhias [a veteran officer who fought well at Halicarnassus in 334] here had not brought the younger men in line when they refused to fight, we should still be delayed around Halicarnassus. How is it then that you think that you have still conquered Asia with young men like that? The truth, I think, lies in what your uncle [Alexander of Epirus, who had campaigned in Italy 334-330] is believed to have said in Italy, that he had faced men in battle and you had faced women.”

Alexander was incandescent with rage now, and threw Cleitus out of the banquet. When Cleitus hesitated to leave, he was pulled away by other officers. Cleitus taunted Alexander with his belief in his divine parentage. Alexander claimed that an oracle told him that Zeus was his “true” father during Alexander’s stay in 333 bc and had offended the Macedonian old guard with such talk. Cleitus said that he himself had been more truthful with him than his own “father” had been.

Alexander was unable to control his anger now and leaped up from his couch. He grabbed a spear from one of the guards and tried to run Cleitus through with it. Ptolemy and another officer, Perdiccas, stopped him and held him back. Alexander, in a drunken rage, called for his men to come to his aid and ordered a trumpeter to sound the alarm. Wisely, the man did not obey this order and was later commended for having the presence of mind to avoid an action that would have had the whole camp at arms. Ptolemy then hauled Cleitus out of the room and over the wall and ditch of the fortress. Cleitus, however, found his way back inside to the banquet and shouted another line from Andromache, “Alas, what evil government in Greece!” Alexander was present and heard this and snatched a spear from one of the guards and thrust it into him. So died Cleitus the Black, slain by the very man whose life he had once saved.

Alexander was aghast at what he had done. He tried to kill himself with the spear as well, but his friends removed the weapon from his hands. He withdrew to his tent where he wailed and wept all night. Cleitus’s body was brought before him. “This is how I have repaid my nurse, whose two sons fell at Miletus to win renown for me,” he moaned. “This is her brother, her only source of comfort after her loss, and he has been murdered by me at the dinner table!” For the next three days Alexander bemoaned what he had done and would eat nothing. Fearing that he was intent on dying and would leave them bereft of a commander in this distant land, his men convinced him to take food.

Spitamenes was Killed as a Peace Offering to Alexander

The officers had Callisthenes of Olynthus, nephew of Aristotle and the expedition historian accompanying the army, try to talk the king out of his haze of grief. His philosophy provided Alexander with little comfort. Then they called in Anaxarchus, a Greek sophist philosopher, who provided Alexander with just the rationale to assuage his guilty conscience. “Don’t you know,” Anaxarchus laughingly said to the king, “why the wise men of old made Justice sit by Zeus? It was to show that whatever Zeus may do is justly done. In the same way all the acts of a great king should be considered just, first by himself, then by the rest of us.” This unfortunate bit of sophistic moral justification, though weak, was just what Alexander wanted to hear. His mood brightened and the Macedonians declared that Cleitus had been justly killed. Alexander held a funeral for Cleitus. Yet another corpse was left in the conqueror’s wake.

More campaigning followed that autumn. More crops were seized or burned. Just a few centers of resistance remained. The months passed. That winter Alexander sent his army to Nautaca and sent a force of cavalry under Coenus, a Companion officer, to cover the frontier against Spitamenes. Alexander’s construction of hill forts in Sogdia denied Spitamenes easy access to the land he had once enjoyed. It was harder now to find food and horses and, in a final throw of the dice, Spitamenes enlisted 3,000 Scythians, and with what followers were left he attempted another raid on Sogdia. The raid was crushed by Coenus. Spitamenes was later killed by the Scythians as a peace offering to Alexander.

Alexander needed a means of keeping the natives peaceful even before he finally left for his often-planned invasion of India. He saw the solution dancing at a banquet held in the fallen citadel of Sisimithres, another Sogdian baron. She was beautiful; indeed, the Macedonians thought her to be the loveliest women they had ever seen with the exception of Darius’s wife. Alexander, perhaps smitten, perhaps seeing a chance to win over her father, Oxyartes, a powerful Bactrian lord, decided to marry her. Her name was Roxane, and though very young, she possessed an uncommon grace and dignity. Alexander and Oxyartes together cut a loaf of bread in half with a sword, as was the custom in Sogdia, and Roxane was his wife. The girl had a husband and Alexander had a new ally.

Alexander’s Bloody Legacy

Oxyartes made his value known soon afterward. By his word alone he managed to convince the commander of another mountain fortress, Chorienes, to submit to Alexander. Alexander allowed Chorienes to keep his stronghold and in return Chorienes gave Alexander a two-month supply of food for the entire Macedonian army. Chorienes made sure that everyone was aware that this was but a small portion of his supplies and that he had submitted of his own free will, not because he was compelled to do so.

In time, Alexander’s measures, both subtle and brutal, brought a quiescence to the region. He could then move on to his planned invasion of India with a relatively secure northern border. However, as many later rulers would find, the Northern Frontier proved difficult to control because of its distance from centers of imperial power and its inaccessibility. The northern territories of Bactria and Sogdia would slip from the grasp of Alexander’s successors soon after the conqueror died in 323 bc.

Was all the bloodshed worth the victory? Alexander had brought thousands of his superbly trained troops to the area and left many of them behind in graves. Many of the natives also perished, either in battle or as a result of the privations inflicted by the constant warfare. Others, most notably the Branchidae, died as a result of unalloyed atrocity. For Alexander, the campaign in the north could only be termed, anachronistically, a pyrrhic victory. Alexander arrived a young and victorious king, but left with the blood of his closest friends and companions on his hands. Philotas, Parmenio, and Cleitus are just the most important of those who died because of Alexander’s surging pride and lust for power. Perhaps we should not shed tears for them, for they were well aware of the bloody rules of the game as it was played in the Macedonian court. Yet, a sense of loss, of needless waste, is impossible to forget when contemplating their deaths.

Just writing to express how fascinated I was by this article. As a greek myself I really enjoyed it rereading about Alexander’s adventures in the far-east as well as learning about events, like the Brachindae, that I have never heard off. Really good job.

The author’s vilification of Alexander can not be justified by the sources. It is part and parcel of an amateur attempt at a more enlightened interpretation of the subject. Presentism is the name relevance is the game.