By Don Hollway

After September 17, 1631, half of Germany feared that God was a Protestant. The other half was sure of it. That day, at the pivotal Battle of Breitenfeld, the revolutionary musketeer brigades and antipersonnel cannons of the “Lion of the North,” Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus II, demolished the outdated pike squares of the Holy Roman Empire. With no army and no commander, Emperor Ferdinand II had nothing left to stop Gustavus and his Protestant allies from marching on Vienna and winning the war.

Secure in his Bohemian estates, midway between battlefield and capital, Duke Albrecht von Wallenstein could be forgiven for saying, “I told you so.” As imperial generalissimo—commander of mercenaries—he had helped raise Ferdinand to supremacy only to be summarily sacked for his efforts and banished from court. Now, thanks to the king of Sweden, he was about to become the most powerful man in the Holy Roman Empire—again.

A Protestant turned Catholic who had fought Muslim Turks in Hungary, Wallenstein cared little for religious quarrels among imperial rulers. “Germany ought to be governed like France and Spain, by a single and absolute monarch,” he believed. In spiritual matters he preferred astrology. (His personal horoscope, cast by no less than Johannes Kepler, proved surprisingly accurate.) His primary belief was in himself. Even as a young son of Czech gentry, Wallenstein had declared, “If I am not yet a prince, I may yet live to become one.” By 1618, he was a rich widower who was serving as military governor of Moravia when Protestant Bohemia rebelled. After Moravia joined the uprising, Wallenstein absconded to Vienna with its entire national treasure, forfeiting his estates to the rebels but gaining imperial favor.

Wallenstein raised a new regiment of cuirassiers, less for glory than for gain. In that brutal age, freebooting soldiers could make their officers rich without ever fighting, let alone winning, a battle. In June 1620, Wallenstein led his mercenaries against Count Ernst von Mansfeld, a Catholic serving the Protestant cause. Barricaded inside their own wagon train, the count and his men might have negotiated surrender had not Wallenstein personally led a breakthrough. Mansfeld escaped, but that November the rebels were defeated at White Mountain, outside Prague.

Wallenstein not only regained his family properties, he bought up 60 confiscated estates at steep discounts, and through a second fortuitous marriage acquired even more, enough for his own little fiefdom. Now with something to lose and not in the best of health—he was plagued all his life by gout—he advised Ferdinand, “With the advantage and the renown, you now have the best opportunity to negotiate a peace.”

Ferdinand’s peacemaking failed, largely because more profits could still be made at war. In 1625, France hired 20,000 mercenaries to join Denmark’s 15,000-man peasant army, and England paid Mansfeld to lead 15,000 more. Planning to crush the Catholic forces between them, they instead ran into Wallenstein with an army the size of both of theirs combined—an army he had raised at his own expense.

Mansfeld advanced to cross the Elbe at Dessau. Wallenstein held the bridge. His problem was getting his vast forces across it into action and, if the fighting went badly, back across again. On April 25, 1626, screened by a cross-river artillery barrage, Wallenstein sneaked a cavalry unit into an unguarded wood and launched a surprise flanking attack. Believing themselves surrounded, Mansfeld’s mercenaries chose to run and fight another day (many of them for Wallenstein). The general reported to Ferdinand, “God has today given me the good fortune to smite Mansfeld upon the head.” The count fled toward Hungary. Within a year he fell ill and died.

With another victory gilding his recruitment pitch, Wallenstein built up his army to 100,000 men—Europe’s largest—yet his men were still mercenaries, loyal only to their paymaster, threatening friend and foe alike. “I have had to make enemies of all the electors and princes, indeed everyone, on the emperor’s account,” the duke admitted. “That I am hated in the Empire has happened simply because I have served the emperor too well.”

By the end of 1628, Wallenstein had driven the Danes out of Germany and back into Norway. “Whatever is now done must be done by sea,” he advised Ferdinand. The emperor accordingly titled him Admiral of the Oceanic and Baltic Seas and directed him to start building a fleet. Gustavus, desiring the Baltic for a Swedish lake and already dabbling at conquest in Poland, took a dim view of such aspirations. “We shall certainly have the Swedes landing on the coast of Pomerania or Mecklenburg,” Wallenstein warned. “Gustavus Adolphus is a dangerous guest, who cannot be too closely watched.”

Ferdinand paid off his warlord with Mecklenburg itself: the fourth largest dukedom in the empire, not coincidentally lying in Sweden’s path to Germany. Furthermore, he promoted Wallenstein to the unprecedented rank of generalissimo, empowered “to ordain and command, orally and in writing, ordinarily and extraordinarily, even as if We in Our Own Person did ordain and command such.”

Emperor in all but title, Wallenstein proved an adept ruler. Spoils and tribute from across the empire flowed through his hands. In turn, he built his dukedoms into military depots, supplying the army with everything from powder and ball to clothing, bread, and beer. He also funded roads and schools, hospitals and almshouses—even an observatory for his favorite astrologer. In the midst of one of history’s most savage wars, Wallenstein forged his own thriving, peaceful little fiefdom.

Yet there could be no real peace within the empire. In 1629, Vienna’s Jesuit mission demanded an Edict of Restitution, essentially turning back the religious clock to pre-Reformation days. Wallenstein, who permitted Franciscans, Lutherans, Calvinists, and even Jews to worship freely, refused to enforce the edict. Against the imperious duke, priests and nobles found common cause: an imperial army might be a wartime necessity, but it was a peacetime expense, too powerful and dangerous for its commander to go unchecked. Ferdinand gave in. Wallenstein was informed that his services would no longer be required. Those hoping the duke would refuse to step down, or even rebel, were disappointed. “Gladder tidings could not have been brought me,” he wrote. “I thank God that I am out of the meshes.”

Much of his army was immediately disbanded; the rest promptly deserted. With the market awash in unemployed soldiers, Gustavus landed promptly on the German coast, calling on the citizens of Mecklenburg to “arrest or slay all the agents of Wallenstein, as robbers, and enemies to God and the country.” At Breitenfeld, Gustavus decisively bested the Imperial army, minus Wallenstein. By the summer of 1632, Sweden was poised to take Vienna and end the war.

Ferdinand sent increasingly frantic letters to Wallenstein begging him to resume command, but the duke was not inclined to comply. His gout had advanced into his hands; he could barely wield a sword, let alone the reins of empire. He agreed only to raise another army. Some 300 officers answered the call, each bringing with him his own company or regiment, 40,000 men in all. When Ferdinand’s son, the king of Hungary, was nominated to lead them, Wallenstein bridled. “Never would I accept a divided command, were God Himself to be my coadjutant,” he said, insisting on terms that precluded another dismissal. It would effectively make him the empire’s first military dictator—at least, after he dealt with the king of Sweden.

Gustavus had amassed perhaps 140,000 men of his own but scattered them to hold conquered territory. With less than 20,000 available for battle, he holed up in Nuremburg and dared the Imperials to come after him. But Wallenstein also preferred to fight from behind defenses. Near a ruined hilltop castle west of town, he built a base four miles square, from which his cavalry tightened a noose around the city. That summer, almost 30,000 Nuremburgers starved. At the end of August, Wallenstein allowed enemy reinforcements and their camp followers to pass within the city walls uncontested, cannily giving Gustavus twice the men but three times the mouths to feed. Sure enough, only a few days later, the Protestants were forced out—all 45,000 of them, the largest army Gustavus ever fielded. For days they prowled around the imperial camp and pounded it with cannons, but Wallenstein held his ground, defying the king to storm the heights.

Unable to use their brigades’ maneuverability or haul their guns up the steep wooded slopes, for 12 hours the Protestant forces fought a literally uphill battle while the imperial forces poured fire down into them. “There was such shooting, thunder and clamor as though all the world were about to fall in,” one observer reported. “The noise of salvoes was unceasing.” Wallenstein led the defense personally, riding back and forth along the ramparts in a breastplate and scarlet cape, tossing handfuls of gold coins to bolster his troops’ resolve. At the rainy end of the day, the Protestants had nothing to show for their efforts but 1,000 dead and twice as many wounded—three times the number of imperial losses.

Gustavus held on for two weeks, but his starving, plague-ridden mercenaries sought easier employment. One entire cavalry company, 80 strong, killed their captain and rode into the imperial camp. The Swedes lost another third of their army before finally slipping away in the night. Wallenstein boasted to Ferdinand that Gustavus had been “repulsed and that the title ‘invincible’ appertains not to him, but to Your Majesty.”

Wallenstein turned north into Saxony for the winter, dispersing his army around Leipzig to cut off the Swedes from their home. That November, with his gout flaring, the generalissimo paused to rest in the little village of Lützen, only to learn that Gustavus had gathered reinforcements and was advancing to attack before the imperials could regroup.

The Leipzig road ran between the armies. Outnumbered, Wallenstein’s men spent the night of November 15-16 digging roadside ditches into trenches and molding the dirt into parapets. By dawn, the Swedes faced a line of earthworks 1½ miles across. Behind it, Wallenstein’s forces arrayed in musketeer brigades heavier than their own.

Thick morning mist delayed the start of battle. To prevent Lützen’s capture, Wallenstein had it burned. Acrid smog blanketed the field, and the two armies pummeled each other blindly all day long, at one point volley-firing muskets at five paces. The Swedes poured into the roadside trenches and almost turned both imperial flanks, but were thrown back again. Gustavus was slain on the field, struck in the head, side, arm, and back by bullets. Wallenstein, so pained by gout that he could no longer ride a horse, led from the comfort of a sedan chair. At one point, a Hessian cavalier missed him with a pistol shot from four paces, and he was hit in the thigh by a spent musket ball. Darkness brought an end to the fighting, leaving both sides on much the same ground they had occupied that morning, now strewn with the dead.

That night Wallenstein pulled back, abandoning the field. Lützen was technically a Protestant victory, but a pyrrhic one. Their advance on Leipzig had been blocked; they had lost more men, more battle flags, and their king. (“It is well for him and me that he is gone,” remarked Wallenstein on hearing the news of Gustavus’s death. “There was no room in Germany for both our heads.”) That night, the Swedes were contemplating their own withdrawal when they learned that the imperials already had left. Lützen wasn’t a matter of who won, but of who retreated last.

At the age of 49, Wallenstein had already led a longer life than most men of the age. Often bedridden, he longed for peace, understanding belatedly that serving the empire and serving the emperor were not the same thing. He rebuffed a Swedish offer to betray Ferdinand, but in May 1633 he proposed to their Saxon allies that “hostilities between the two armies be suspended, and that the forces should be used in combined strength against anyone who should attempt further to disturb the state of the Empire and to impede freedom of religion.”

By 1634, Ferdinand still needed an army, but not a generalissimo. Wallenstein was declared a traitor, his estates forfeit. Lamenting that “I had peace in my hand; now I have no further say in the matter,” Wallenstein surrendered his command. Escorted by a regiment of dragoons under Irish colonel Walter Butler, Wallenstein and a few loyal officers fled to Eger on the border with Saxony, held by Scots-Irish troops with nothing binding them to Vienna but their mercenary oaths. Uncertain who to obey, garrison commander Lt. Col. John Gordon made the ex-duke welcome. It would be a brief respite.

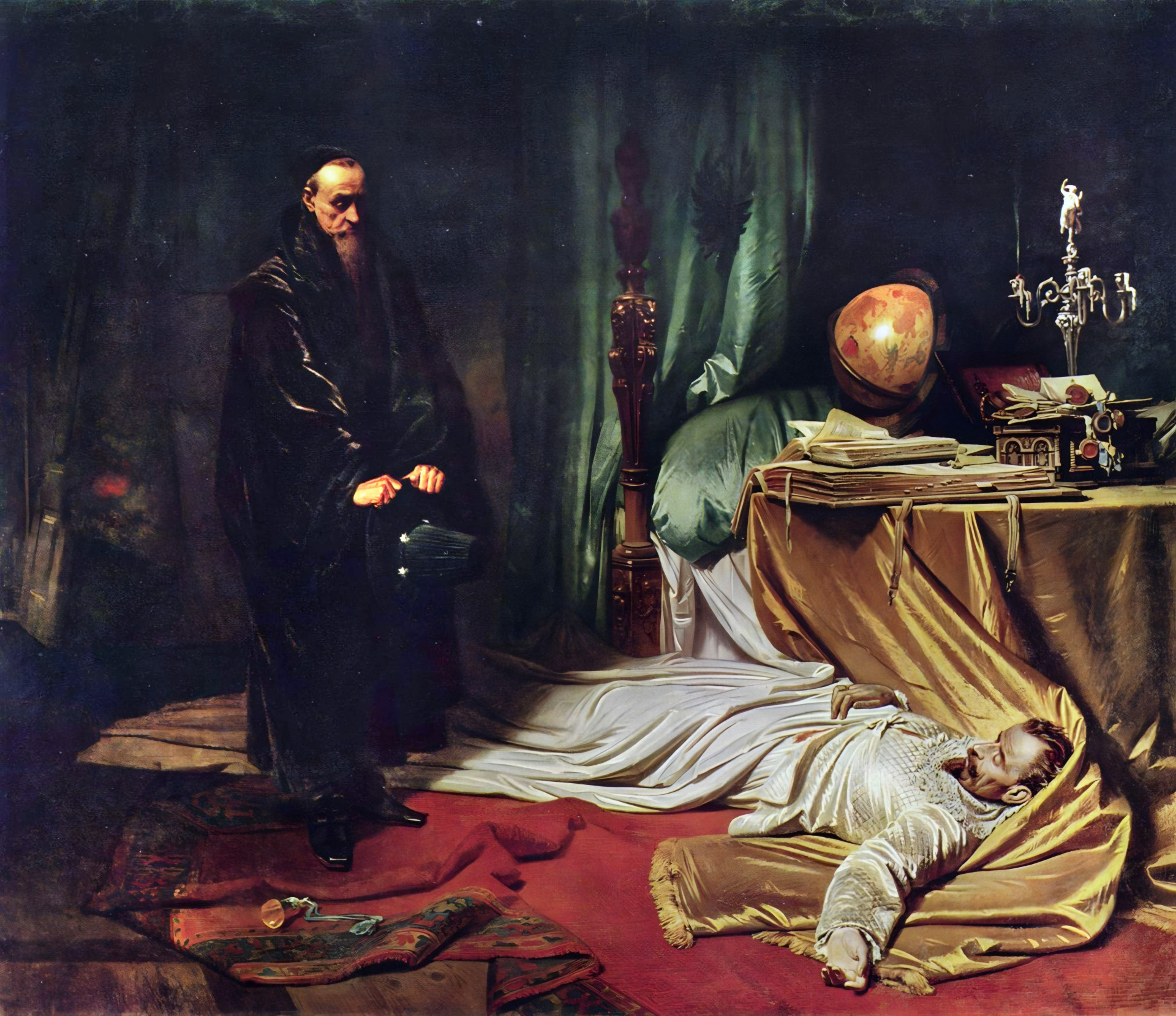

On the night of February 25, Gordon invited his guests to dinner in the town castle. Wallenstein was too ill to attend, but his officers were wined and dined to the point of drunkenness, at which time Gordon’s men burst in and cut them down. Meanwhile, Butler and a handful of dragoons broke into Wallenstein’s quarters. Captain Walter Devereux raced up the stairs and kicked open the bedroom door. Wallenstein shouted for mercy, but Devereux stabbed him to death with a polearm.

The assassins profited well by their treachery, although most soon died by war or plague. Ferdinand was forced to abandon the Edict of Restitution and sue for peace with Saxony—just as Wallenstein had advised. “When the different countries are laid in ashes, we shall be forced to make peace,” Wallenstein had foreseen. No one knew the price of peace better than the old mercenary. He just didn’t live to see it.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments