By R. Jeff Chrisman

He was seemingly everywhere—Poland, France, Holland, Italy, and the western front during the last days of the Third Reich. Yet his name is less well known than that of other German military figures such as Rommel, Rundstedt, Manstein, Guderian, Jodl, and Dönitz.

Albert Konrad Kesselring began his military career as a staff officer in the Bavarian Army during the Great War. He was an architect of the new German armed forces between the wars, and then a field marshal in the Luftwaffe and a ground-forces commander with unique command authority in World War II.

But it was his service in Italy during the last half of World War II that made Kesselring famous, and infamous, to the rest of the world. His command of the months-long German withdrawal up the Italian boot made him a defensive specialist of wide renown. Unfortunately, atrocities committed by subordinates in Italy were, rightly or wrongly, blamed on him and brought post-war charges of war crimes and murder.

Albert Kesselring was born at Marktsteft, near Würzburg in Bavaria on November 30, 1885. His father was a schoolteacher, but Albert knew from a young age that he wanted to be a soldier. Kesselring volunteered for the Royal Bavarian Army in July 1904 as a Fahnenjunker (cadet) and was commissioned a Leutnant (lieutenant) on March 8, 1906, serving in pre-war engineering and artillery units. His first taste of air service was in 1912, when he trained as a balloon observer with the Bavarian Airship and Motor Transport Battalion, where he soon learned from personal experience that balloon service required a strong stomach.

During World War I, Kesselring served as an adjutant and staff officer in several Bavarian Army artillery units and was decorated with both classes of the 1914 Iron Cross. It was during this time that young Albert gained and honed his understanding and appreciation of tactics and leadership, as well as the notice of his superiors for the first (but not the last) time.

Instead of being mustered out, Kesselring was selected for the post-war German Reichswehr and, in October 1922, was assigned to the Reich Defense Ministry. The officer corps of the Reichswehr was deliberately insulated from politics; for them, there was to be only one guiding principle—the military oath.

In January 1924 Kesselring was assigned to the Truppenampt (Troop Office) under the head of Army Director General Hans von Seeckt, where he became deeply involved in secretly building the foundation and framework of the new German armed forces, the Wehrmacht.

Seeckt was convinced that military aviation would be required to secure Germany’s future, and he secreted a small group of officers—Kesselring, Hugo Sperrle, and Walther Wever, among others—to see to its development. Between the wars Germany and Russia had a secret agreement whereby Russia would clandestinely provide training facilities for German pilots. Kesselring was involved in the planning and development of the secret training and made several trips to Russia in the 1920s.

On October 1, 1933, he was discharged from the army and assigned to the newly created Air Ministry, where he was made chief of the Administration Office with the rank of Commodore.

In the 100,000-man Reichswehr, rank advancement was exceedingly slow. But in the brand-new air force, promotion came quickly—Kesselring was promoted to Generalmajor (brigadier general) on April 1, 1934, and then to Generalleutnant (major general) on April 1, 1936. Although he was one of the architects of the Luftwaffe, which became known as a National Socialist institution, Kesselring was never a member of the Nazi party.

Kesselring worked tirelessly toward his goal of building up the fledgling Luftwaffe into a force equivalent to the army or the navy. At the time, there was debate raging about the fundamental nature of the Luftwaffe: should it be a tactical force or a strategic force? Kesselring believed the optimum use of the Luftwaffe and its limited funds would be as a tactical force, directly supporting ground operations. With Kesselring now chief, his view prevailed.

Kesselring’s tenure as chief of staff lasted less than a year. Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring transferred him to Dresden, promoting him to General der Flieger (Lt. Gen. of Aviation), and making him commander of Luftkreis III (Air District III) on June 1, 1937. Kesselring was elated—he would now have a chance to put the theoretical knowledge he had amassed into practical use.

In early 1938 Kesselring was transferred to Berlin to take command of Gruppenkommando 1 (Air Command 1). A year later, when Poland was invaded on September 1, 1939, Gruppenkommando 1 was upgraded to Luftflotte 1 (Air Fleet 1), putting Kesselring in charge of the full range of air units—from reconnaissance and transport wings to fighters, bombers, and dive bombers.

Luftflotte 1 was attached to Army Group North for the Polish campaign and performed well, working closely with the ground troops as they struck targets in Poland. Kesselring’s Stuka dive bombers were particularly effective in support of General Guderian’s XIX Corps as its panzers surged across the breadth of Poland in barely two and a half weeks. At the end of the campaign, several high-ranking officers, including Kesselring, received the Knights Cross of the Iron Cross directly from Hitler on September 30, 1939.

In January 1940 the commander of Luftflotte 2, General Hellmuth Felmy, was relieved of command and replaced by Kesselring. Luftflotte 2 was scheduled to play a large part in the upcoming invasion of France and the Low Countries, where it would be attached to Army Group B. Kesselring was specifically responsible for the airborne operations against the Netherlands and for protecting the forces attacking across Belgium to the Channel coast.

Once again, the German forces surged through the enemy with the help of Kesselring’s ground-attack air units. The combination airborne/glider operation in Holland was only partially successful, but the glider-borne assault on the fortress of Eben-Emael was a complete success, with Kesselring’s troops holding both the fortress and the nearby bridges over the Albert Canal by the end of the first day.

On May 14, just four days after the attack had commenced, Holland surrendered, persuaded in part by Luftflotte 2’s heavy bombing of Rotterdam; by May 20, panzer units were closing in on the channel coast.

The ensuing Allied evacuation from Dunkirk brought German air forces into contact with units of the RAF for the first time. The evacuation from Dunkirk also produced the first major conflict over objectives between Hitler and his military leaders, principally Reichsmarschall Herman Göring, which in turn produced the first strategic turning point in the war.

Göring persuaded Hitler to hold back the ground troops that had surrounded Allied forces at Dunkirk and instead allow Luftflotte 2 to destroy the enemy as he tried to escape from the beach.

Kesselring was aghast. He told Göring that it couldn’t be done by fresh pilots, let alone by pilots that had been through three weeks of hard fighting. In the event, thanks in large part to the interdiction by RAF fighters, Luftflotte 2 failed to destroy the enemy troops on the beach or in the water—just as Kesselring had predicted. This allowed the British Expeditionary Force and over 100,000 French troops to escape and fight another day.

In a lavish ceremony at the Berlin Opera House on July 19, 1940, Hitler bestowed the field marshal’s baton on 12 generals, including Kesselring, in celebration of their swift victory in the west. Kesselring, a General der Flieger, jumped over the rank of Generaloberst directly to Generalfeldmarschall.

While German ground units continued the attack through southern France, Luftflotte 2 remained on the channel coast preparing to launch an air attack on Britain preliminary to a full-blown invasion from the sea.

The first phase of the air assault began on July 10 with Kesselring’s flyers attacking coastal shipping convoys and harbors. On August 8, the attacks turned to airfields, radar installations, and other military targets in Southern England. On August 24 the attacks were expanded to include the London area.

Another turning point was reached on September 7, when Hitler switched Luftflotte 2 to terror attacks on civilian targets in London exclusively. This switch in targets allowed the RAF, which had been severely attritted by attacks on its airfields, to regain its footing and in fact, to survive.

The survival of the RAF, in turn, meant that the Luftwaffe could not gain air superiority over England or the Channel, and therefore the planned German invasion of England could not go forward. Luftflotte 2 remained in France and continued bombing England night after night until May 1941, when Kesselring and Luftflotte 2 were transferred back to Germany to prepare for Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union.

Luftflotte 2 flew in support of Army Group Center—in the capable and familiar hands of the now-Generalfeldmarschall Fedor von Bock—in Barbarossa beginning June 22, 1941. Once again, German troops surged deep into enemy territory with Kesselring’s ground-attack air units leading the way.

Blitzkrieg was at its zenith. By November 30 Kesselring’s flyers had destroyed 6,670 Russian aircraft, 1,900 tanks, 26,000 motor vehicles, and 2,800 trains.

In late November 1941, just as the German attack on Moscow was reaching its climax, Kesselring and Luftflotte 2 were transferred to Italy to help the flagging Axis effort in the Mediterranean. Kesselring, in addition to his Luftwaffe duties, was also made Oberbefehlshaber Süd (Commander-in-Chief South).

For the next 20 months, Kesselring was right in the middle of what was surely one of the most byzantine and convoluted command arrangements ever known. He reported to Hitler on strategic matters, to Göring for Luftwaffe matters, and to Mussolini for operational matters. On the one hand, he had to gently prod the Italians into action without stepping on their very sensitive feelings; at the same time, he had to encourage the German commanders’ cooperation with the Italians and mitigate any frustration that flared due to Italian reluctance. All the while, both Germans and Italians were protective of their own national interests—Machiavellian in the land of Machiavelli, as one observer put it.

The Mediterranean-North African theater had been a quagmire for the Germans long before Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring arrived. The Italian armed forces were poorly led and were constantly having to be bailed out of one predicament or another.

It was to prop up the Italians that Hitler had sent a few divisions and a corps headquarters to Libya in February 1941. Commanded by Generalleutnant (Major General) Erwin Rommel, the Afrika Korps was to push the British out and secure the Mediterranean coastal area of North Africa. Unfortunately, the British, with bases on Malta, were very well placed to disrupt the German supply route to North Africa.

Kesselring’s mission was to establish air superiority over the Mediterranean, closing it to British shipping and eliminating Malta as a threat. Kesselring believed that to neutralize Malta, it would have to be occupied, but Hitler and Göring scoffed at the idea, expecting that aerial bombing would suffice.

Kesselring initiated bombing raids on Malta immediately and found quick success, causing a slackening of pressure on German shipping. German shipping losses, formerly in the 70-80 percent range, quickly fell to 20-30 percent. In fact, by February 1942, British bombing units were forced to relocate from Malta to Egypt. For these early successes Kesselring received the Oak Leaves to the Knights Cross on February 25, 1942.

Kesselring was then charged with creating a plan for the invasion of Malta and produced the first draft—code-named Operation Herkules—in mid-May. Unfortunately, during the first week of May, German bomber strength in the region had been reduced by 50 percent and fighter strength by 35 percent when part of Luftflotte 2 was rushed back to the Eastern Front.

The loss of air superiority over the entire Mediterranean was now only a matter of time. With Malta’s defenses growing stronger and German ground forces in the theater being consumed by Rommel in the desert, Operation Herkules was cancelled by Hitler shortly thereafter.

Rommel’s pursuit of the British into Egypt had stalled at El Alamein in early September, and he was finally defeated there by Bernard Montgomery’s Eighth Army at the end of October. Panzer Army Afrika began to withdraw from Egypt on November 4, 1942, marking the end of large-scale German offensive operations in North Africa.

Four days later, the Allies landed in French North Africa in Operation Torch, creating a totally different strategic situation with Allied ground forces now both east and west of Panzer Army Afrika.

Kesselring, always the master of every contingency, reacted quickly and ordered the establishment of two bridgeheads in Tunisia—one at Tunis and another at Bizerte, the only deepwater ports in the country—to protect it from Allied incursion from the west. Kesselring immediately started to round up troops wherever he could find them and sent them to Tunisia. On the 12th they seized Tunis and its airfield.

At first there were mainly Luftwaffe air and ground units and some paratroops in Tunisia, but by the 25th there were nearly 25,000 German and Italian troops with 64 tanks holding the two bridgeheads. By the middle of December, the Allied advance had been temporarily repulsed west of Tunis, and the two bridgeheads had been joined into one 50-mile-wide bridgehead covering both Bizerte and Tunis.

Rommel’s withdrawal reached the Tripoli position in mid-January 1943. Tripoli, as the heart of Italian North Africa, was full of service troops and civilians who now saw their futures in jeopardy. Less than a week, later Rommel resumed his withdrawal and Tripoli was evacuated. By the end of the month Panzer Army Afrika had taken up positions along the “Mareth Line” in southeastern Tunisia, forming the southern boundary of the enlarged German bridgehead.

The loss of the Italian colony in North Africa was a severe shock to the Italian command and particularly to the Italian people, and it served to bring into sharp focus the threat to their homeland. This in turn made all the leadership suspicious of each other. The Italians became suspicious that the Germans would try to disarm them and take over their country, while the Germans were suspicious that the Italians would go over to the Allies behind their backs. No one trusted anyone.

But it was clearly Kesselring who made the strategic decisions in Tunisia, and they were mostly correct. Rommel had wanted to pull out of the Mareth Line and withdraw all the way to Gabes at the first sign of enemy attack preparations, fearing an enemy outflanking maneuver. But Kesselring insisted on a staged withdrawal, and events proved him right, producing an orderly retreat into the mountainous stronghold of northern Tunisia without excessive losses.

Rommel had completely lost faith in the Mediterranean campaign and the Italians. He thought that abandoning most of Italy up to the far north was the right course of action and filled Hitler’s ears with his reasons.

Kesselring argued that Italy was infinitely defensible; a long, narrow strip of land, much of it mountainous, that, if defended in-depth, could take months for an enemy to fight its way through.

He recognized that its long coastlines made an amphibious landing behind the front a possibility, but Kesselring would keep reserves near each coast to contain any such assault and knew he could react quickly enough to deal with this eventuality.

By April 1943 it was clear to most everyone involved that the Tunisian bridgehead did not have long to live, and with it the entire Axis presence in North Africa. It was being inexorably squeezed from the east and the west, and supplies and reinforcements had been reduced to a trickle.

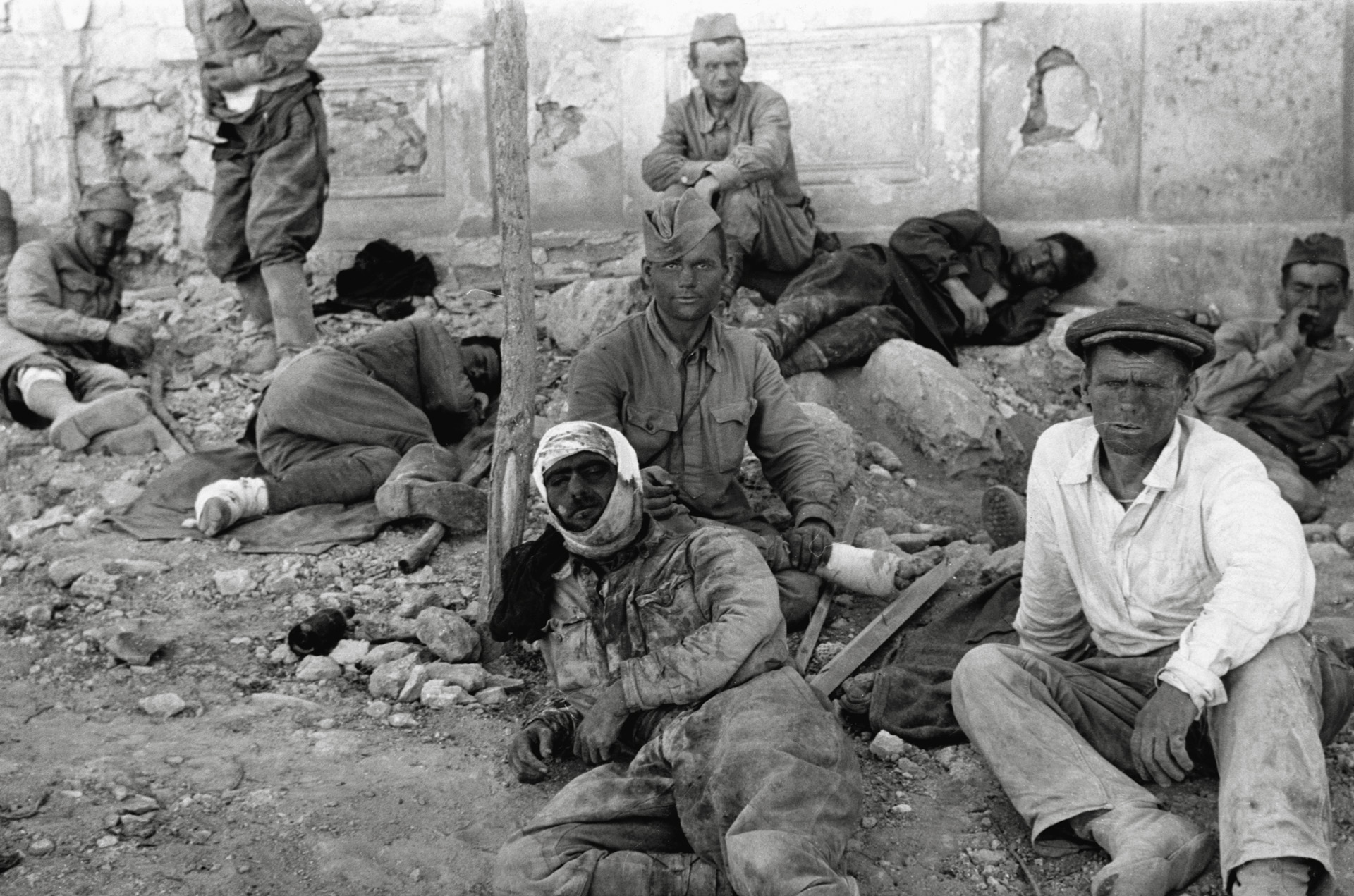

Kesselring tried to evacuate key men and specialists but mostly in vain. Generaloberst (General) Hans von Arnim. Kesselring, who had replaced Rommel in command of Army Group Afrika, was forced to surrender on May 12, 1943. Immense sadness overtook Kesselring; he wished he’d done more but knew that he couldn’t have.

Hermann Göring pounced immediately on Kesselring for the loss of Tunisia. Formerly referring to Kesselring as a model of the “modern thinking General,” Göring now ranted that he was “State enemy Number One!” Fortunately for Kesselring, Göring’s prestige and influence over Hitler was in a state of rapid decline, so his denigrations carried little weight.

Kesselring’s delicate balancing act between German needs and Italian capabilities became all-consuming, and on June 12, 1943, Generalfeldmarschall Wolfram von Richthofen took over command of Luftflotte 2, allowing Kesselring to concentrate on the big picture—and the big picture was not pretty. With Tunisia gone, it was only a matter of time before the Allies invaded Italy or the Italians surrendered and invited them in, and everyone knew it.

The change in command made Kesselring responsible for all Axis ground, air, and naval units in the Mediterranean and North Africa. He thereby became the first and only German theater commander to command all three branches simultaneously.

Kesselring assumed that the Allies’ next target would be within range of land-based aircraft in Tunisia; this ruled out France, northern Italy, and the Balkans, and made southern Italy the most likely target—specifically, the Italian off-shore islands: Corsica, Sardinia, or Sicily first, then the mainland.

The Italian plans for the islands’ defenses were excellent, but the preparations and fortifications had not been started. Kesselring set out immediately to get defenses built, gently hounding the Italian commanders and cajoling the German high command to quickly send materials and equipment.

Kesselring’s tactical sense told him that the Allies’ first target would most likely be Sicily, so he focused his attention there. By the end of June Kesselring had managed to augment the defenses on Sicily—not to the point that they could throw back an Allied invasion, but they could at least delay an attacking force until reinforcements arrived.

The field marshal then tried to recede into the background to give the Italians an opportunity to demonstrate their steadfastness in defending their homeland.

The Allied invasion started in the early hours of July 10, and almost immediately the Italians showed their true colors. The Italian coastal divisions were a complete failure; the few counterattacks that were executed were weak, late, and easily pushed aside. Several units, including the entire “Napoli” Division, simply melted away. The fortress of Augusta, on the southeast coast, surrendered without even being attacked. The question at this point was whether these actions were due to incompetence or treachery.

Kesselring flew to Sicily to take direct command on the 12th and found mostly chaos. The Italian units were on the verge of collapse, and the two German divisions were the only troops fighting. Kesselring immediately ordered the abandonment of western Sicily and called in the1st Parachute Division from France; they began landing that evening at Catania.

His intent was to first block the Allies’ push north along the east coast, as this was the fastest route to Messina and a short crossing to the mainland, then build a blocking force across the northeastern tip of the island, forming a bridgehead around Messina.

On July 25, the political situation was thrust back into the foreground when Mussolini was deposed. This was a precondition by the Allies for the Italian surrender, and the pace of that process now quickened. King Victor Emmanuel III assured Kesselring that there would be no change to Italy’s prosecution of the war, and that he had been forced to dismiss Mussolini because he had lost the goodwill of the public.

Kesselring took Victor Emmanuel at his word, but Hitler was incensed; his first reaction was a scheme to kidnap the royal family as insurance against treachery. Hitler also saw Kesselring as an Italophile who was under the spell of the Italians. “That fellow Kesselring is too honest for those born traitors down there.” he mused.

Hitler wanted to make a show of force—flying in troops to Rome to take over the government and moving in forces to secure the border area of the Brenner Pass in the Alps. Kesselring counseled caution: The Fascists had been deposed because the people were thoroughly tired of war and its strain, but the people weren’t necessarily Germany’s enemies. Bold military intervention in Rome, he argued, would immediately produce a violent confrontation, which the Germans did not need. Kesselring advised a calm approach; there was nothing to lose by staying in touch with the Italians, he said.

Kesselring held several meetings with the new chief of Commando Supremo and slowly maneuvered him into agreeing that they should work together, and eventually—“by seduction not rape,” as the official U.S. history of the war puts it—the Brenner Pass was turned over to German control.

In the midst of the political fireworks and intrigue came the first display of Kesselring’s real talent: the masterful withdrawal from Sicily that he orchestrated in the middle of August. Dropping back in stages during the hours of darkness, German and Italian troops withdrew to Messina and then safely across the straits to the mainland in barely a week’s time. Over 114,000 German and Italian troops, 14,332 vehicles, 135 guns, 47 tanks, and almost 22,000 tons of ammunition, stores, and equipment were successfully withdrawn.

Fortunately for the Axis, the Allies did not immediately jump across the Strait of Messina to the mainland. Kesselring found this quite surprising, but he took advantage of the Allies’ pause to distribute his forces and build up defenses.

Reports from Sicily and North Africa convinced Kesselring that the Allies’ next target would be the mainland rather than one of the other offshore islands. It was also clear that the Allied forces on Sicily would, sooner or later, attack across the Messina Strait into Calabria.

Kesselring left only Italian units to defend against such an attack and withdrew most German troops from the tip of Calabria. He concentrated on defending farther north and in the Naples-Salerno area, which he considered the most likely target of the main Allied invasion.

On September 3, Montgomery’s Eighth Army crossed the Strait of Messina in Operation Baytown and landed at Reggio de Calabria virtually unopposed. Italian troops laid down their arms, and German rearguard units began withdrawing, blowing bridges and raising obstacles as they went—the first of what would be hundreds of obstacles built and bridges destroyed by German engineers in Italy over the next several months.

Early on September 8, with reports of over 100 vessels escorted by battleships and aircraft carriers heading north, it became clear that the Allied invasion was imminent. Just after noon, 131 B-17 Flying Fortresses of the U.S. Army Air Force struck Frascati, the Roman suburb where Kesselring’s was located. The headquarters was destroyed, communications completely cut, and hundreds killed.

The Germans subsequently found a map in the wreckage of a downed bomber that had Kesselring’s headquarters clearly marked. Kesselring thought this a clear indication that not all Italians could be trusted. In truth, coded “enigma” signals intercepted by the British were more likely the source of the information.

Four hours after the bombing at Frascati, Kesselring got word over the public telephone line from General Jodl at German high command that the Allied Supreme Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, had announced the Italian surrender on the radio. Jodl also issued the order for Operation Achse, the disarming of the Italians.

Hitler wanted all Italian soldiers disarmed, arrested, and sent to POW camps in Germany. In the north, Rommel did just that—arresting all he could get hands on and sending to Germany those who would not cooperate with his troops. Kesselring, on the other hand, opened negotiations with the Romans and came to an agreement: Rome would be declared an “open city” and be secured by military police only, and the Italian soldiers would turn in their arms and be allowed to go home.

Therefore, in central and southern Italy the disarming and demobilization of the Italians went very smoothly; some were still friendly to the Germans, and many just wanted to return home.

The German high command criticized Kesselring for not having arrested the Italians, and Rommel berated him for it. Later, however, as local militias engaged in guerilla warfare against the Germans, it was much more vigorously pursued in the north; Rommel’s heavy-handedness was more antagonizing than Kesselring’s diplomacy.

The morning after the Italian surrender, September 9, 1943, the Allied invasion began. As Kesselring had expected, the main landing took place at Salerno, with a small subsidiary landing at Taranto. XIV Panzer Corps units in the vicinity moved in to block off the U.S. Fifth Army’s landing beaches. The LXXVI Panzer Corps hurried north from Calabria.

It appeared Hitler had written off Kesselring’s 70,000 German soldiers in central and southern Italy after he refused Kesselring’s request that Army Group B (in northern Italy) send him two divisions to shore up his defense against any landings. Hitler wouldn’t even allow Rommel to send units south to make contact with Kesselring’s troops in the vicinity of Rome. Presumably, Hitler had accepted Rommel’s suggestion to abandon all but the northern reaches of Italy.

The units at hand near Salerno managed initially to hold the attackers to the immediate vicinity. German counterattacks over the next several days caused the Allies to consider a withdrawal, but in the end their heavy naval gunfire suppressed the defenders and allowed the Allies to consolidate.

On the 17th, Kesselring ordered his troops to begin forming defensive lines across Italy from just north of Naples, along the Volturno River, then across the country to Cerignola on the Adriatic. The Volturno Line, running from the Tyrrhenian and Ligurian Seas on the west to the Adriatic on the east, was to be the first of these lines.

Kesselring’s troops held the Volturno Line until October 16 and then began an orderly withdrawal to the Bernhardt Line, some 20 miles to the north. As they withdrew, they sowed mines and built traps and obstacles that delayed their pursuers at every turn.

By early November Kesselring’s troops had taken up positions in the Bernhardt Line and awaited the Allies’ first assault. That was all Hitler needed; on November 4, 1943, he told Kesselring that he should continue his line-by-line defense as long as possible.

On the 16th, Kesselring’s command designation was changed to Oberbefehlshaber Südwest (Commander in Chief Southwest) and Commander, Army Group C, giving him complete command of all forces in Italy; on the 21st, Rommel’s Army Group B relocated to Fontainebleau near Paris.

The primary defensive line south of Rome was known as the Gustav Line, and positions there had been under construction for several months. It bristled with concrete bunkers and gun pits, turreted machine-gun emplacements, barbed wire, and thousands of mines. By early January 1944, the Gustav Line was fully manned by Kesselring’s troops after an orderly withdrawal from the Bernhardt Line.

By mid-January both the British Eighth Army and Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark’s American Fifth Army had engaged the German troops holding the Gustav Line, but neither made much progress.

On January 22, to the complete surprise of the German troops at hand, the Allies made an amphibious landing at Anzio, about 56 miles up the west coast from the Gustav Line and only some 40 miles south of Rome. Kesselring immediately began rounding up units wherever he could find them and rushing them to Anzio, but once again something surprising happened.

The Allies, although they were virtually unopposed, did not seek to move inland immediately but seemed content to consolidate their beachhead and land supplies. This was all the head start Kesselring needed, for by the evening of the next day he had sufficient troops on hand to contest any breakout the Allies might attempt. By the end of the month, he had most of seven divisions, 95,000 men, deployed around Anzio.

The terrain at Anzio completely favored the German defenders: the beach gave way to reclaimed marshland and then a range of mountains that encircled the entire area. The Germans held the mountains and could rain artillery fire down onto anything that moved. This control of the commanding heights meant that the Allies could not directly threaten the rear of the units holding the Gustav Line, making it unnecessary for the Germans to pull back from it.

For the next four-and-a-half months, the combatants at both Anzio and along the Gustav Line pounded each other with artillery, and attack followed counterattack—neither side making any appreciable gains.

However, all that changed during the third week of May. On the 20th, Clark’s Fifth Army broke through the Gustav Line southwest of Cassino, near the coast. This drew the attention of the Germans ringing the Anzio bridgehead just enough that, three days later, the U.S. V Corps was able to break out of the bridgehead.

Making the situation even more dangerous for the Germans, the two Allied forces linked up three days later, putting two U.S. corps essentially behind German lines. But then, rather than turning east and surging behind the German units holding the Gustav Line, the Allies turned northwest toward Rome.

Once again, Kesselring didn’t need an engraved invitation; he ordered a withdrawal to the “C Line” north of Rome. On June 4, the Allies entered Rome nearly unopposed, almost exactly nine months after they had landed at Salerno—nine months that Kesselring had kept them from reaching Rome. In July Kesselring received the Diamonds to the Knights Cross for this achievement.

One must consider the duration and distance of some other campaigns during the war to appreciate the magnitude of Kesselring’s achievement. For instance, Rommel in the campaign in the West in 1940 surged through Luxembourg, Belgium, and France with his 7th Panzer Division, covering 185 miles in 21 days, or 8.8 miles per day. George Patton’s Third Army during the invasion in 1944 covered 385 miles in 21 weeks, or 2.6 miles per day. Georgi Zhukov’s counterattack at Moscow in 1941/1942 pushed 262 miles through Army Group Center in 135 days for an average of just 1.6 miles per day.

Now consider Kesselring’s delaying actions throughout the length of Italy: By the end of 1944, the Allies had covered 320 miles from Salerno to just south of Bologna, but it had taken them 479 days. That’s only two-thirds of a mile per day.

But Kesselring wasn’t in Italy at the end of the year; he was in the hospital with a fractured skull. In late October, the field marshal’s car was careening through the mountains after dark with no lights when a truck pushed a large artillery piece out from a side road in front of his car. Kesselring’s driver was killed.

After only 12 weeks in the hospital, Kesselring returned to Italy and resumed command in January 1945. The front had not changed much, thanks mostly to the foul winter weather and the Allies’ distractions on other fronts. In fact, the front still hadn’t changed when he left again on March 9 to succeed General Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt as High Commander in the West (OB West).

With German-controlled territory rapidly shrinking, OB West was renamed OB Süd on April 22, commanding southern Germany, Italy, and the Balkans. One week later, General Heinrich von Vietinghoff, who had succeeded Kesselring in command of Army Group C, signed the documents to surrender Italy; Kesselring promptly fired him, and tried to have him arrested. Of course, the war was all but over, and six days later General Field Marshal Albert Kesselring surrendered, as well.

After the war, many German Generals were charged with war crimes, and Albert Kesselring was no exception. He was, however, considered only a minor war criminal. Many aspects of the prosecution remain controversial to this day, but the details, while fascinating, are beyond the scope of this article.

The charges against Kesselring boiled down to his taking reprisal against Italian civilians after partisans ambushed a German patrol in Rome. On May 6, 1947, the court found him guilty as charged and sentenced him to death by firing squad.

Many British officers who had fought against Kesselring came to his defense, and former Prime Minister Winston Churchill immediately branded the sentence too harsh. Well-known American military historian S.L.A. Marshall was quoted in a newspaper article in May 1947: “The verdict would appear to be that Kesselring, in taking reprisal, overstepped the bounds. But what are the bounds? … I believe that Kesselring was the victim of unavoidable circumstance and that any competent commander put in the same position would have found it impossible to come through with clean hands.”

On July 4, 1947, Kesselring’s death sentence was commuted to life in prison, and in October 1952 he was released from prison on the grounds of ill health.

After his release, Kesselring became active in several veterans’ organizations and wrote his memoirs. Albert Kesselring—regarded by many as one of Nazi Germany’s few “honorable” soldiers—suffered a heart attack and died in Bad Nauheim, West Germany, on July 16, 1960. He is buried at the Bergfriedhof in Bad Wiessee, Bavaria.

The animal in the photo does not appear to be a mule. More likely it is a Martina Franca donkey.

An Asino di Martina Franca.

There has been a fair amount of criticism of Mark Clark’s handling of the Italian campaign, but the terrain definitely favored the defenders, and Kesselring was a crafty opponent.

More audacity by Clark might have offset those factors, but his was a difficult task at best.