By Major General Michael Reynolds

By the morning of July 27, 1944, General Omar Bradley’s First U.S. Army had won the “Battle of the Hedgerows” in Normandy and stood ready to break out to the south. It had taken four corps, ultimately employing 12 divisions, to do it, and the cost had been appalling —XIX Corps alone had suffered 10,077 casualties. The forthcoming operation, codenamed Cobra, was designed to outflank SS General Paul Hausser’s depleted Seventh German Army and finally rid northern France of the hated Boche.

“The Left Flank has Collapsed”

A day later half a dozen German infantry divisions had been cut to pieces and U.S. columns were pouring down the roads between Coutances and the River Vire. Even the Americans were astonished by their success. Two days later, August 1, General George S. Patton’s Third U.S. Army became fully operational, and his 4th Armored Division, after advancing 40 kilometers in 36 hours, reached Avranches. The German Commander in Chief West, Field Marshal Gunther von Kluge, warned Berlin, “The left flank has collapsed.”

Bradley, who was now commanding the U.S. Twelfth Army Group, ordered his successor in First Army, General Courtney Hodges, to seize the Vire–Mortain sector, while Patton was to turn west into Brittany. In a characteristic feat of organization and personal leadership, George Patton funneled seven divisions down one road and across the one bridge at Avranches in 72 hours.

It is not the author’s intention to discuss the higher strategy of the Normandy campaign with all the arguments about wasted efforts in Brittany and large and small envelopments. For the purposes of this article, it is sufficient to say that Mortain was captured by August 2, and the following day Bradley ordered Patton to leave minimal forces in Brittany and use his main strength to drive eastward. Rennes was secured on the 4th, and the overall Allied ground commander, General Sir Bernard Montgomery, issued a directive that ended, “The broad strategy of the Allied Armies is to swing the right flank towards Paris and to force the enemy back to the Seine.”

The Mortain Counterattack

Montgomery was not the only person to issue a new directive on August 4. Hitler did the same. He ordered von Kluge to launch a counteroffensive from the Vire–Mortain area, aimed first at Avranches, with the objective of cutting off all American forces to the south of that line, and then northeast to the Channel coast to drive the Allies back into the sea. It was a highly imaginative plan, but both von Kluge and Hausser knew that it would be impossible to assemble the forces necessary for such an offensive before the collapse of the entire front to the west of the River Orne. They also knew that there was no point in arguing!

Hitler insisted that eight of the nine panzer divisions in Normandy should be used in the offensive, along with the entire reserves of the Luftwaffe, but that the attack should be delayed until “every tank, gun and plane is assembled.” Every detail was specified, including the exact roads and villages through which the assaulting troops were to advance. General Gunther Blumentritt, von Kluge’s chief of staff, complained after the war, “All this planning had been done in Berlin with large-scale maps and the advice of the generals in France was not asked for, nor was it encouraged.” The operation was codenamed Luttich (Liege). The Americans called it the “Mortain counterattack.”

In accordance with Hitler’s directive, at 1935 hours on August 5, the commander of the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte (Bodyguard) Adolf Hitler—usually shortened to Leibstandarte or LAH—received an order to dispatch his two panzer battalions and two of his panzergrenadier battalions, plus a self-propelled artillery battalion, to the area to the southeast of Vire, that same night. This elite division had already suffered heavy casualties during July and was at this time still heavily engaged southeast of Caen. Nevertheless, within five hours it had been relieved by an infantry division and the designated units had begun their move to the west. For the time being, the rest of the division remained in Army Group B reserve.

When Patton’s tanks approached Le Mans the following day, von Kluge began to panic. It was clear that the German southern flank was wide open, but he was reassured by Berlin that he “should not worry about the extension of the American penetration, for the delay [in launching the counteroffensive] would mean cutting off so much more.”

Assembling the Counterattack

Von Kluge and Hausser knew that the Führer Order was sounding the death knell of the German Seventh Army and that any delay in launching the counterattack would only exacerbate matters. They therefore resolved to attack during the night of August 6, long before all the necessary forces could be assembled. They were encouraged in this decision by a visit to Seventh Army on the afternoon of August 6 by a Luftwaffe general, who said 300 fighters could be committed over the attack area on August 7. Although this new plan fell far short of Hitler’s vision of a campaign-winning counterstroke, he surprisingly agreed to the earlier attack.

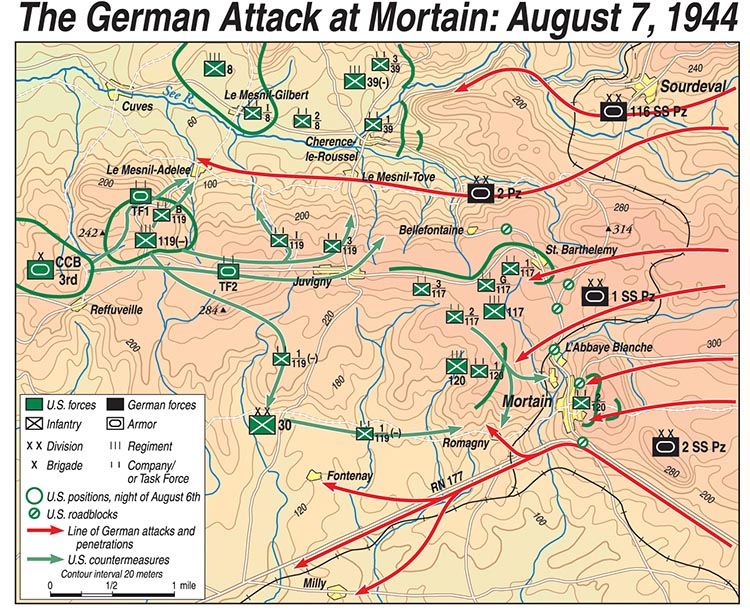

The Germans had detected only one U.S. infantry division and part of an armored division in the path of their attack. Against this relatively small force von Kluge and Hausser planned to use General Hans von Funck’s XLVII Panzer Corps with the 2nd and 116th Panzer Divisions, 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich with a battlegroup from the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division, and, they hoped, those parts of the Leibstandarte already mentioned. According to Hausser in his postwar interrogation, “The main body of the 1st SS Panzer Division … was to serve as a second wave in the attack on Juvigny.”

Von Funck’s counterattack was to be launched between the Sée River in the north and the Sélune in the south. Although not significant barriers, these small rivers would at least give the flanks of the offensive some protection. The main German thrust was to be in the center, through St. Barthélemy and Juvigny, initially by General Smilo Freiherr von Lüttwitz’s 2nd Panzer Division. Since his division had suffered some 40 percent casualties to its combat strength, von Lüttwitz was to be strongly reinforced by the Leibstandarte’s 1st SS Panzer Battalion and by another panzer battalion and antitank company from the 116th. This was expected to give von Lüttwitz a strength of about 100 tanks.

It was envisaged that by the time the breakthrough by 2nd Panzer had been achieved, the rest of the Leibstandarte would have arrived and be able to lead the final advance to Avranches. The remainder of the relatively fresh but by now seriously weakened 116th Panzer Division, with only about 25 tanks, was to protect the northern flank by advancing from the area west of Sourdeval to engage enemy forces north of the Sée. Its initial objective was le Mesnil-Gilbert.

SS Brigadier Otto Baum’s reinforced 2nd SS Panzer Division was only about 60 percent combat effective and had fewer than 30 tanks. Its task was to capture Mortain by encirclement and then advance west and southwest to St. Hilaire, while Panzer Lehr’s reconnaissance elements looked after the southern flank.

“I Must Say This is a Poor Start”

Although well under 200 tanks would be available for the assault on August 7, it was hoped that a sufficient number of tank reinforcements and replacements would be furnished during the advance by the arrival of the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions and a tank Battalion of the 9th Panzer Division.

At 1630 hours on August 6, SS Major General Teddy Wisch, commanding the 1st SS Panzer Division LAH, reported that his tanks, having driven 70 kilometers, would need refueling and that anyway, they could not possibly arrive in the planned assembly area before 2200 hours.

Two hours before the designated H hour of midnight, von Funck reported to Hausser that the leading elements of the Leibstandarte were still at Tinchebray, some 20 kilometers short of their required positions. The remainder of the route, through St. Clement, was narrow and winding, with high banks skirting the poor roads and a deep valley to be crossed. It was obvious that there was no chance of the 2nd Panzer Division receiving its extra LAH tanks in time for the planned attack. Similarly, Lt. Gen. Graf von Schwerin’s 116th Panzer Division had failed to produce its share of extra forces for 2nd Panzer, with the result that von Funck asked that von Schwerin be sacked.

Inevitably, von Funck, Hausser, and von Lüttwitz were extremely unhappy with the way things were going—the latter was missing not only his extra tanks but also an assault gun brigade and additional artillery that had been promised from the II Parachute Corps. Hausser is recorded as saying, “I must say this is a poor start. Let’s hope that tonight’s loss of time will be compensated for by fog tomorrow morning.”

The 30th Infantry Division, Old Hickory

Facing the German onslaught, General Hodges had basically just one division—the 30th Infantry, nicknamed Old Hickory. It had already suffered badly in the Normandy fighting. Between July 7 and 13, during the attack on the Vire, it had incurred 3,200 casualties, and on the 25th another 662 fell to “blue on blue” attacks by American aircraft. Its attached tank battalion, the 743rd, suffered 38 tank and 133 personnel casualties during July, but most of these had been replaced.

Old Hickory’s move to the Mortain sector on the morning of August 6 was more like a celebration than a move into battle. It was a warm bright Sunday, and the local citizenry thronged the roads to wave, throw flowers, and offer drinks to the passing soldiers. At Mortain itself, hotels and cafés were open and crowded with customers, and when the men of the 1st Infantry Division, whom they were relieving, told the GIs that there was not a German within a hundred miles who wanted to continue the fight, they began to relax and look forward to a few days of rest.

It looked like it would be an easy ride to the Seine and Paris. The only thing to mar their pleasure was when some of the later convoys were strafed by several flights of German fighter bombers. The men had no way of knowing that within six hours of their commander assuming responsibility for the Mortain sector they would be engulfed by Hitler’s latest offensive.

Major General Leland Hobbs deployed the 30th Infantry Division with the 120th Infantry Regiment, less a battalion required for a separate task, in the town of Mortain and on Hill 314 immediately to its east and the 117th Infantry Regiment in St. Barthélemy and the area to its west. He held the 119th Infantry, less a battalion detached to the 2nd Armored Division, in reserve about five kilometers to the west of Juvigny. Each regiment had a tank destroyer company of the 823rd Tank Destroyer Battalion in support. On Hobbs’s right flank the VII Corps cavalry was reported to be covering to a point some 14 kilometers south of Mortain, and he was told that the 39th Infantry Regiment of the 9th Division was four kilometers to his north, and the 8th Regiment of the 4th Infantry Division to the west of that. He had no direct contact with any of them. In fact, the 30th Infantry Division was dangerously exposed on both flanks.

The Counteroffensive Begins

The leading elements of the Leibstandarte reached Tinchebray just two hours before Operation Luttich was due to be launched. Four hours later, at 0200 hours on the 7th, only the 1st SS Reconnaissance Battalion, 1st SS Panzer Battalion (not more than 43 Panthers and seven Mk IV tanks), and the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Regiment in armored personnel carriers (SPWs) had arrived. The Reconnaissance Battalion joined the right wing of 2nd Panzer’s thrust toward le Mesnil-Tôve, and the rest of the force, under SS Major Herbert Kuhlmann, formed a major part of the left assault group aimed at Juvigny.

It is interesting to note that although Hausser’s chief of staff, Colonel Rudolf von Gersdorff, later used the delayed arrival of the LAH Panzer Battalion as an excuse for the German failures on August 7, the Leibstandarte did not accept that it was to blame. It claimed, not unreasonably, that it had only a short summer night to travel 70 to 80 kilometers across the supply routes of two armies engaged in full-scale combat and with three panzer divisions and the entire II SS Panzer Corps moving along the same march route just ahead of it.

The XLVII Panzer Corps attack ran into difficulties from the start. In the northern sector, von Schwerin’s 116th Panzer Division got nowhere. It had been unable to disengage properly before the planned H hour and did not even attempt to advance until 1630 hours. At 2050 hours, its highly decorated commander was sacked. In the south, Baum’s 2nd SS Panzer Division was more successful. It encircled Mortain, mainly from the south, and advanced as far as Romagny, two kilometers to the southwest.

When the morning fog lifted, however, U.S. artillery and Allied air power threatened any further advance, and a halt was called. A major factor in this situation was the valiant and undefeated stand by the surrounded 2nd Battalion of the 120th Infantry Regiment of Old Hickory on Hill 314, which was to go down as an epic in American military history. The battalion lost more than 300 men killed and wounded during the siege that followed.

No less critical were the actions of a platoon of A Company, 823rd Tank Destroyer Battalion, and men of the 120th Infantry at the l’Abbaye Blanche roadblock to the north of the town. They inflicted astonishing casualties against the northern thrust of 2nd SS Panzer and remained undefeated when the Germans finally withdrew four days later.

Leibstandarte: A Weakened Division

But how did the Leibstandarte fare? There are many misconceptions regarding its status at the time of the attack and how it might have been employed. Most books, and indeed some German reports, talk about “the 1st SS Panzer Division” as though it was a complete entity, and many American writers describe it as one of the strongest and best-equipped divisions in the German Army. Nothing could be further from the truth. Such statements ignore the fact that the Leibstandarte had been virtually destroyed on the Eastern Front less than four months previously, rebuilt using large numbers of draftees from the Luftwaffe and Navy, and had lost more than 1,000 men and some 40 tanks and armored assault guns in the three weeks before Luttich.

During the night of August 5, when it was relieved south of Caen for the move to the west, the Leibstandarte had only 43 Panthers, 55 Mark IVs, and 29 assault guns combat ready. On the day of the attack it did not even exist as a coherent panzer division. Only three of its subunits reached the concentration area before first light on the 7th, and they had been allocated to another division anyway. Yet another part of the LAH, Kampfgruppe (KG) Schiller, with a composite battalion of SS panzergrenadiers, an artillery battalion, a mortar battery, and four or five assault guns, had been subordinated to an infantry division to help stem an Allied attack south of Vire; and the balance of Wisch’s division—two SS panzergrenadier battalions, about 20 assault guns of the 1st SS Sturmgeschütz Battalion, and the 1st SS Pioneer Battalion—was still on the move toward the Mortain area. It had not even reached St. Clement when darkness fell on the first day of the attack.

Indeed, some elements, including a company of Mark IV tanks, failed to begin their move west until the night of the 7th and took until the 10th just to get to Domfront. Hitler’s criticism of von Kluge for not committing the LAH as an exploitation force through 2nd SS Panzer in the southern sector on the morning of the 7th, with which some historians have agreed, ignored reality.

The right-hand group of von Lüttwitz’s 2nd Panzer Division, including the Leibstandarte’s Reconnaissance Battalion, made reasonable progress during the early hours of the 7th. Its attack route lay down a narrow, wooded valley as far as Bellefontaine, but then the country opened up and the way to the west was relatively unrestricted. At 0315 hours the Americans reported an enemy penetration between the 117th and 39th Infantry Regiments in the vicinity of le Mesnil-Tôve.

Further reports said that at least 20 tanks, supported by infantry, forced the Cannon Company of the U.S. 39th Infantry to abandon its vehicles and guns in that village. Before 0800 hours this force reached the outskirts of le Mesnil-Adelée, where a company of the reserve 119th Infantry Regiment had established a roadblock. The Germans were 10 kilometers from their start point but still 25 kilometers from Avranches. By then, as with Baum’s advance southwest of Mortain, they were vulnerable to Allied artillery and air power and out on a limb. The column halted.

Advancing on St. Barthélemy

At 0730 hours Combat Command B of the 3rd Armored Division was attached to the 30th Infantry, and one combat team was given orders to restore the situation in conjunction with the 3rd Battalion of the 119th and a company of the 743rd Tank Battalion. The combined force was to strike north from Juvigny to retake le Mesnil-Tôve and if possible cut off the Germans. With the failure of the 116th Division to advance on its right, von Lüttwitz’s column was indeed vulnerable on both flanks. The 3rd Armored Division’s tank and infantry combat teams advanced shortly after 1310 hours, forcing the Germans to fight hard to hold le Mesnil-Tôve. The Americans lacked the strength to break through, however, and by last light the LAH’s Reconnaissance Companies were successfully defending the western and southern approaches to the village.

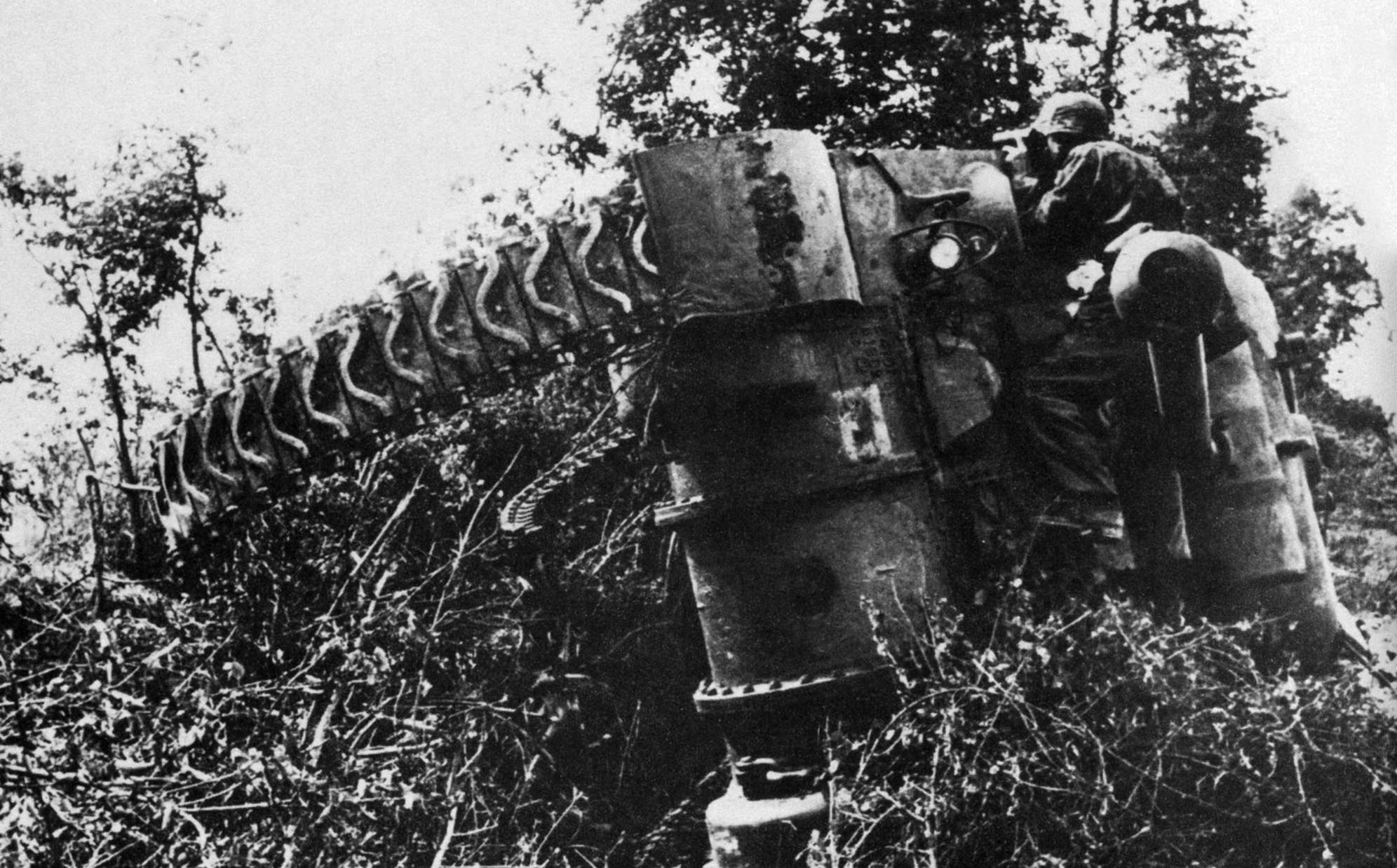

Despite the delays already mentioned, the Panthers and Mark IVs of Kuhlmann’s 1st SS Panzer Battalion were ready to move forward from their assembly area to the east of St. Barthélemy by 0430 hours on the 7th. They had been joined by the 3rd SS Panzergrenadier Battalion in its SPWs, but the forming-up area proved too cramped and the prospect of advancing in thick fog over unseen ground so soon after an exhausting approach march could not have been attractive.

In fact, had Kuhlmann and his men been able to see what lay ahead of them they would have been appalled. The initial part of their route was through very close country with high banks along the narrow roads. There was no chance of deploying cross-country, and visibility was restricted, even without the fog, to less than 100 meters. They would therefore have no chance to use their splendid tank guns effectively. But worse was to come. Although the country opened out beyond St. Barthélemy, they were destined to advance along a high, narrow, whale-like ridge toward Juvigny with no cover whatsoever from the dreaded Allied fighter bombers.

At 0550 hours, following a 45-minute artillery barrage on the American positions in and around St. Barthélemy that did little damage, the Leibstandarte tanks moved in from the east and southeast and the 2nd Panzer Division’s Mark IVs and assault guns from the north and northeast. The village was held by A and C Companies and three 57mm antitank guns of Lt. Col. (later Maj. Gen.) Robert Frankland’s 1st Battalion of the 117th Infantry. They were supported initially by four 3-inch tank destroyers of 3rd Platoon, B Company, 823rd Tank Destroyer Battalion, and later by two guns of the 1st Platoon of the same company. Company B of the 117th was in reserve farther along the ridge to the west of the village in an area called le Foutai (known to the Americans as le Fantay).

“Tanks Have Broken Through”

Frankland had been expecting to move into a simple assembly area and was surprised to find he was required to defend the village. His battalion strength was 828, but 190 of these men had joined the unit only within the previous three days. Everyone was tired from being on the move all day, there were no detailed maps of the area, and some of the foxholes and outposts vacated by the 1st Infantry Division had to be occupied in darkness. This was particularly serious for the tank destroyer crews who found many of the former positions of the self-propelled armored M-10s of the 1st Infantry totally unsuitable for their low-slung, towed guns.

Kuhlmann was also in for a surprise. He had been expecting to drive straight through St. Barthélemy, but he soon found that he had to clear the southern part of the village in order to get onto the Juvigny road—the 30 or so Mark IVs and the assault guns and grenadiers of the 2nd Panzer Division had been ordered to attack the northern sector of the village only. The fog, which rose and fell like a stage curtain, made it difficult for attacker and defender alike, and in chaotic fighting most engagements took place at less than 50 meters. In some cases, the fighting was hand to hand. The tanks were unable to deploy, and conditions generally could not have been more unsuitable for an armored attack. Even so, by 0808 hours the Panthers had broken into the C Company positions. At 0810 hours Frankland gave orders that the panzers were to be allowed to pass through. This tactic caused many casualties to the SS grenadiers as they tried to follow up behind the tanks.

According to the 30th Infantry Division log, the 117th Regiment reported at 0922 hours, “Everything under control…,” but it went on to say, “We have no reserve and have to shuttle troops back and forth.” Within the hour the picture changed dramatically. The regimental log shows the following entry timed at 1035 hours: “… tanks have broken through A and C Companies and heard [sic] advancing toward B Company.” The log also shows that at 1046 hours the 1st Battalion Command Post (CP) at la Rossaye, 1,100 meters west of the village church, was under attack. The 117th Infantry Regimental CP was only 400 meters to its south.

At 1130 hours the Army Group B war diary placed KG Kuhlmann 1,000 meters west of St. Barthélemy, and this is confirmed by the log of the 117th Infantry, which states that at 1125 hours enemy “tanks and infantry are on the road advancing toward the Regimental CP from St. Barthélemy.” At this time Frankland’s battalion was desperately trying to establish a defense line at la Rossaye, but things were getting so bad that A Company of the 105th Engineer Combat Battalion, supporting the 117th, had to be called in to provide protection for the regimental CP. It claimed a Mark IV tank knocked out at 1200 hours, and this has to be added to the main claim, by B Company of the 823rd TD Battalion, of eight enemy tanks destroyed in the St. Barthélemy sector during the morning, with two more probables. All six tank destroyers were lost in the process, as were the three infantry 57mm antitank guns.

At 1218 hours a temporary defensive line had been built up on the high ground east of the CP, but there were no reserves. The 2nd Battalion of the 117th Infantry had been placed under the command of the 120th Regiment at 0315 hours to help meet the crisis at Mortain. The 3rd Battalion was holding the north flank between Juvigny and St. Barthélemy, and the two remaining battalions of the reserve 119th Regiment were busy trying to hold le Mesnil-Adelée and to recapture le Mesnil-Tôve. No tanks were available to help out because the 743rd Tank Battalion, permanently attached to the 30th Infantry Division, was operating in support of the 119th and 120th Infantry Regiments. The only heavy weapons left were the other five TDs of B Company, 823rd TD Battalion, which had been sited to cover the St. Barthélemy–Juvigny road.

Frankland’s command had by now lost seven officers and 327 men, many of them prisoners, and the TD Company had lost 43 men. In after action interviews made shortly after these events, Lt. Col. Frankland told how about 25 men of A Company, another 55 men of C Company, and a battered platoon of B Company worked their way back to the line finally established that afternoon but then received the heaviest concentration of artillery fire they had ever experienced. Some men fought and hid in isolated bands for two days before they succeeded in rejoining their companies.

“The Day of the Typhoon”

Nevertheless, in spite of everything the Americans had delayed the Germans for six critical hours, and there is no doubt that the resistance at St. Barthélemy against both KG Kuhlmann and the elements of von Lüttwitz’s 2nd Panzer Division, during a period when bad weather prevented ground attack aircraft from intervening in the battle, was crucial to the success of the American defense on August 7. The leading elements of KG Kuhlmann were still some three kilometers short of Juvigny when the first British and Canadian Hawker Typhoon ground attack aircraft appeared overhead shortly after 1230 hours.

The 300 aircraft promised by the Luftwaffe had never materialized. On the Allied side it had been agreed that the British and Canadian Typhoons, armed with rocket projectiles, would deal exclusively with the enemy’s armored columns, while the American fighters and fighter bombers of U.S. Maj. Gen. “Pete” Quesada’s IX Tactical Air Command would operate farther afield, preventing enemy aircraft from interfering with the Allied air effort and destroying German transport and communications leading up to the battle area.

The result of this agreement was that once the morning fog lifted the German armored columns were at the mercy of dedicated ground attack aircraft. August 7 has been called “The Day of the Typhoon” with good reason.

At 1215 hours six Royal Air Force reconnaissance aircraft spotted the German tanks and motor transport at St. Barthélemy. From then on, until 2040 hours, the armored columns of the XLVII Panzer Corps were exposed to a furious and nonstop attack. There were never fewer than 22 Allied aircraft over the Mortain sector during this period, and at the height of the attacks, between 1500 and 1600 hours, no fewer than 88 Typhoons were in the air. A total of 458 individual Typhoon sorties were flown on August 7, of which 271 struck the German forces in the Mortain sector. Of these Typhoons, 247 were armed with anti-armor rockets and 24 with 500- or 1,000-pound bombs. A further 131 sorties attacked targets around and to the east of Vire and for various reasons another 56 failed to find targets. Only four aircraft were lost.

The Americans, who flew some 200 sorties, had rendered the Luftwaffe completely impotent. The daily report of Hausser’s advance CP recorded the following statement for August 7: “Continuation of the attack during the midday hours was made impossible because of enemy air superiority.”

Result of the Air Attack

Exact German losses on this day will never be known. RAF pilots claimed a total of 84 tanks destroyed, 35 probably destroyed, and 21 damaged, plus a further 112 other vehicles destroyed or damaged. The IX U.S. Tactical Air Command, which flew 441 sorties during August 7-10, made claims of 69 tanks destroyed, eight probably destroyed, and 35 damaged, and 116 other vehicles destroyed or damaged.

Confirmed results on the ground were somewhat different. During August 12-20, 1944, operational research teams from both the Twenty-First Army Group and Second Tactical Air Force conducted separate investigations in the battle area and then compared and collated their results. They found 34 Panthers, 10 Mark IVs, three self-propelled guns, 23 armored personnel carriers, eight armored cars, and 46 other vehicles. Of the 44 tanks, they concluded that 20 had been destroyed by ground fire, seven by Air Force rockets, two by bombs, four from multiple causes, and 11 either abandoned or destroyed by their crews. It is impossible to say how many damaged vehicles the Germans managed to recover. Seventeen Panthers were found in the area over which the LAH had operated (13 in the vicinity of St. Barthélemy, with the most westerly pair being found 1,700 meters west of the church) and of these six had been knocked out by Army weapons, four by Air Force rockets, and the rest blown up or abandoned by their crews.

Arguments about who stopped the German advance are futile. Without the stubborn resistance of the 30th Infantry Division and 823rd TD Battalion, elements of von Funck’s forces might well have reached the vicinity of Avranches before the arrival of the Typhoons. The consequences could have been dramatic. Equally, had the Typhoons not intervened when they did there is a distinct possibility, some would say probability, that the Germans would have broken through to the west. But these are the ifs of history. As with most successful operations in modern warfare, it is cooperation among all arms and between ground and air forces that are the essential ingredients.

Inevitably, in the confused fighting of the day, there were numerous cases of attacks on friendly troops. The 117th Infantry Regimental log records three instances of strikes on its units by Allied aircraft, the first timed at 1505 hours. It asked for further planned missions to be called off! Friendly fire incidents, however, were not restricted to the RAF; in the fog some troops were hit by friendly artillery and even small arms fire. As one tank destroyer man put it, “We didn’t have a friend in the world that day.”

The history of Old Hickory makes it clear that the events of August 7 brought the 30th Infantry Division to the brink of disintegration, but incredibly it held and the Germans were prevented from making their breakthrough.

Renewing the Attack

At 1930 hours Hausser presented von Kluge with three alternatives: hold on until annihilated, withdraw toward the east and allow an Allied breakthrough to the northeast, or fall back toward the northeast and allow the Allies a free run toward Paris. Because Hitler would not even consider withdrawal, the inevitable order came back to renew the attack as soon as further troops could be made available. In the meantime, the situation was to be improved as far as possible and maintained at all costs.

During the night of the 7th, the remainder of the Leibstandarte, less KG Schiller and some Mark IV tanks, arrived in the St. Barthélemy sector, as did the 3rd Battalion of the U.S. 12th Infantry Regiment (4th Infantry Division), with six tanks and four TDs in support. This new American group reinforced Frankland’s depleted battalion, which now had a total strength of 465 but an offensive combat strength of only just over 200.

Sometime after first light, the 1st and 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Battalions of the LAH’s 2nd Regiment advanced toward Juvigny and Bellefontaine, with support from tanks and artillery limited owing to early morning fog. The Germans say they captured both locations but could not hold them. There is no evidence to support this claim.

The Americans say their attack in the same area by the 3rd Battalion, 12th Regiment and Frankland’s B Company, with tank and TD support, began at 0800 hours. After fighting all day, claiming two enemy tanks and gaining only a few hundred meters, the American force pulled back. The SS Panzergrenadiers in St. Barthélemy were not to be moved easily.

The 2nd Panzer Division’s northern group, including the LAH’s Reconnaissance Battalion, had a much more difficult time in the le Mesnil-Adelée and Mesnil-Tôve sector. It was attacked by Task Force 1 of Combat Command B of the U.S. 3rd Armored Division and the 3rd Battalion of the 119th Infantry Regiment. Task Force 1 comprised the 1st Battalions of the 33rd Armored and 36th Armored Infantry Battalions, and the combined force managed, after heavy fighting, to advance to and capture le Mesnil-Tôve by 1945 hours. This still left the Germans holding the high ground to the east of the village.

Stalemate in St. Barthélemy Sector

Although that same evening von Kluge told Hausser that he must risk everything and attack again as soon as possible, another event was already heralding the end of the German offensive. At 1700 hours on August 8, 100 kilometers southeast of Mortain, tanks of Maj. Gen. Wade Haislip’s XV U.S. Corps crossed the Gambetta bridge and rolled into the center of Le Mans. For the moment, however, the Germans in the Mortain sector continued to strengthen their positions, and the following day a Leibstandarte reconnaissance company occupied Bellefontaine while engineers of the 1st SS Pioneer Battalion strengthened the northern part of St. Barthélemy. Elements of the 1st SS Panzergrenadier Regiment also thickened up the line. Consequently, when the Americans launched their attack in this sector with the same force as on the 8th, they got nowhere.

In the east of the le Mesnil-Tôve sector a penetration by the 3rd Battalion of the 119th Infantry was stopped by an immediate counterattack from elements of 2nd Panzer, and German artillery fire completely crippled attempts by tanks of Task Force 1 of the 3rd Armored Division to support this attack. The divisional history speaks of very heavy casualties.

During the afternoon of the 9th, Hitler replaced von Funck with General Heinrich Eberbach and gave tentative orders for the Avranches counteroffensive to be relaunched on August 11 with the main thrust still through Juvigny—in the LAH sector. The new command, which was to be subordinate to Hausser, was to be called Panzer Group Eberbach and comprised, in name only, two panzer corps, the XLVII and LVIII. Needless to say, most of the officers on Hausser’s staff realized that if this last attempt to break through to Avranches failed, the Seventh Army would be encircled and doomed.

During August 10, the Leibstandarte continued to hold its positions in the St. Barthélemy sector. The fighting was bitter and bloody, but the Germans were husbanding their armor for the next phase of Luttich. Although the Americans made some minor dents in the German defenses, they were not strong enough to evict their enemy. In fact, for obvious reasons, a continuation of the status quo suited both Bradley and Montgomery.

The Inevitable Withdrawal

By now the American push toward Alençon was causing von Kluge grave concern, and he asked the supreme command for Panzer Group Eberbach to be transferred temporarily from the Mortain area for use against the American spearheads thrusting northward into the underbelly of the Seventh Army. The Führer did not respond; despite this, Hausser gave orders for the 116th Panzer Division and parts of the LAH to be transferred to the LXXXI Corps in the Alençon area.

On August 11, Hitler recognized the inevitable and approved Hausser’s Alençon plan. At 2300 hours the Leibstandarte began its withdrawal. The field of battle belonged to the Americans, and Operation Luttich was over.

Michael Reynolds is a retired major general in the British Army. He is a veteran of the Korean War and the former director of NATO’s Military Plans and Policy Division. Reynolds is a recognized expert on the Battle of the Bulge. He initially directed and later appeared as a guest speaker on some 50 British Army and NATO battlefield tours in the Ardennes. Since retiring from the Army, he has written several well-received books on the subject.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments