By Edward G. Miller

An air strike intended to cover the landing of 1st Lt. John McGowan’s team of six Alamo Scouts was late. The U.S. Navy Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat carrying the team landed in broad daylight a half mile from shore instead of the planned quarter mile, and it was impossible to remove the fully inflated rubber landing boat from the plane.

The GIs had to deflate it before putting it into the water, then lost more time inflating it before paddling to shore on Los Negros Island, located about 250 miles north of Papua New Guinea. Somehow they made it without alerting the thousands of Japanese defenders who were within a few hundred yards of their landing site.

Hiding the boat was another matter: “The hiss of air as it escaped from the rubber boat sounded to them as if a thousand locomotives were letting off steam,” stated Training Director Major Gibson Niles. Once in a hiding position on shore the scouts waited out the air strike—it finally occurred at 10 am on February 27, three hours later than planned.

Clad in camouflage suits, faces streaked brown and green, the team edged into the overgrowth. They found newly dug trenches and machine-gun emplacements, clear evidence that the enemy, contrary to reports from air reconnaissance, was present in force. About 15 apparently well-conditioned enemy soldiers wearing new-looking uniforms walked by the team’s hiding position. McGowan froze as one of them appeared to look him straight in the eye before turning away to join the others.

By 1 pm, it was clear that the team was in danger of detection. They were unable to cross a creek separating them from Momote airfield, which was the objective of their mission and any future American ground attack, so McGowan decided to return to the landing beach and radio for pickup. They spent the night undetected, and at dawn on February 28, 1944, McGowan radioed his report to the PBY.

Los Negros was “lousy” with the enemy. They upset the U.S. Navy pilot, who only slowed his plane to pick up the Alamo Scouts. According to Niles, “he never stopped taxiing, and actually picked up the team on the run.” The first mission of the famed Alamo Scouts was over.

McGowan and his team reached New Guinea before 10 amthe same morning, where he briefed the Sixth Army commander, Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, and his G-2 (intelligence officer), Brig. Gen. Charles A. Willoughby.

Brigadier General William C. Chase, the commander of the 1st Cavalry Brigade (one of two brigades in the 1st Cavalry Division), realized the Scouts’ report conflicted with another that had reached him and his division’s G-2 a few days before: “Bomber crews say Los Negros and Manus are evacuated” (1st Cavalry Division G2 Journal entry for 11 pm, February 26, 1944).

This aerial reconnaissance of Los Negros and Manus detected only two dilapidated airfields. There were no active Japanese gun positions, aircraft, or troops visible to the airmen. Lt. Gen. George Kenney, commander of the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) air forces, took the information to his boss, General Douglas MacArthur. Kenney evidently accepted without question the air reconnaissance report, which clearly conflicted with that of Lieutenant McGowan.

Los Negros and Manus Islands are the two largest of the group called Admiralty. These islands helped link Japan’s scattered island defenses and barred an Allied advance from the Southwest Pacific to the Philippines. The Admiralties also formed a valuable natural fleet anchorage, Seeadler Harbor.

They also offered the Japanese a base valuable in helping them concentrate the aircraft so vital to protecting their own naval bases. An Allied capture of the Admiralties would also help seal off the Bismarck-Solomon Islands area from reinforcement and isolate more than 100,000 enemy troops. Despite their expansive area of influence across the Pacific, the Japanese could not hold every mile of coastline or every island capable of basing aircraft.

The Allies in fact did not need to attack major concentrations of enemy troops in the southwest Pacific as long as they could find suitable locations for airfields on lightly defended islands in their general area of interest. Even the strongly defended Japanese fleet base at Rabaul was at the end of a long logistical line and thus inherently vulnerable to Allied air attack.

Nine months before John McGowan’s Alamo Scout team landed on Los Negros, MacArthur’s SWPA staff in May 1943 outlined a plan to neutralize Rabaul and take the Admiralty Islands. General Krueger received orders to that effect in November and again in mid-February 1944. The target date for the Admiralty Islands attack was April 1, but much depended on the capability of Japanese naval and air forces to counter the Allies.

Successful air attacks and naval surface raids in February, meanwhile, led SWPA planners to lower their estimate of Japanese capabilities for air operations. The aerial reconnaissance report appeared to corroborate the estimated impact of the Allied raids. This news, if confirmed by ground reconnaissance, might enable MacArthur to advance the April target for seizure of the Admiralties. Moving earlier would keep the enemy from reinforcing the islands and presumably save American lives.

Success might also help MacArthur advance his case for giving priority to his plan of liberating the Philippines instead of devoting scarce resources to targets favored by the Navy in its Central Pacific drive.

MacArthur’s G-2, General Willoughby, disagreed with Kenney’s assessment and maintained that the importance of the islands as a link in the chain between Rabaul and Japan was the reason that the enemy would defend them strongly. Instead of the near absence of the enemy, his staff on February 23, the day of the aerial reconnaissance, calculated that there were likely as many as 4,000 defenders in the Admiralties.

However, his published estimate added “bureaucratic cover” in case Kenney was correct. That is, barge sightings at Los Negros might, according to a 1st Cavalry Division field order, “indicate that the Japanese had evacuated the place.”

What was MacArthur to make of the conflicting estimates from two of his key subordinates? He approved advancing the date for the invasion of Los Negros but simultaneously hedged his bet by authorizing only a reconnaissance in force, not a full-scale attack, to begin on February 29.

Yet the 1st Cavalry Division’s field order directing the attack maintained that “recent air reconnaissance … results in no enemy action and discloses no sign of enemy occupation.” Troop commanders thus entered the battle with radically different intelligence assessments.

Krueger was certainly concerned. He did not like the idea of advancing the attack date, and he strengthened the initial troop list from the 800 authorized by SWPA to more than 1,000. Maj. Gen. Innis P. Swift, commander of the 1st Cavalry Division, recommended a force twice that size in part because the division was new to combat.

The cavalrymen and attached units would land near the Momote airstrip on Los Negros Island. A detachment from the Australian New Guinea Administration Unit (ANGAU) would accompany them, gathering intelligence and dealing with the civilian islander population as their villages were liberated.

After the Sixth Army staff received MacArthur’s order, they immediately revised their working plans for the Admiralty operation, now codenamed Brewer. Krueger called General Swift to Army headquarters on February 24 and told him the operation would commence on the 29th and that it would be a reconnaissance in force, not a full-scale attack.

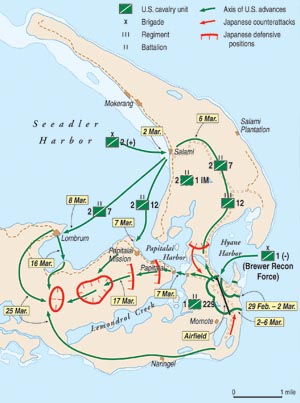

Because Swift’s staff had already prepared a terrain study, logistical study, and an enemy order of battle for the Admiralty Islands, the major changes in the earlier plans involved landing on the southeastern coast of Los Negros instead of the northwestern coast, and the relatively small number of troops (Brewer Reconnaissance Force) involved.

Five days (February 24-29) did not give much time to assemble, load, and move the cavalrymen 500 miles from their bases to the landing beach. There would also not be enough time for air strikes on enemy targets that could support the defense of the Admiralties, nor for the Navy to make hydrographic surveys of Seeadler Harbor and the approaches to the landing beaches on both Los Negros and Manus, the follow-on target.

Naval gunfire support plans were essentially to be developed during the course of the attack based largely on the Alamo Scouts’ report. The air plan called for heavy and medium bomber attacks beginning 28 minutes before landing and continuing until the first wave was ashore.

In fact, the operation began with German government maps and charts dated 1908 and supplemented with topographical maps based on aerial photos only. About the only thing planners knew with certainty was that aerial photos showed significant drawbacks in the landing area at Hyane Harbor on Los Negros. Troops would have to pass through a narrow (mile-wide) gap in the coast to gain the beachhead. Flanking fire was a danger. Once through this, only half the harbor had shores suitable for landing troops and equipment.

The planners understood from the locals that there were about 2,500 defenders on the island. Despite the aerial reports that Momote field appeared undefended, islanders reported through intelligence channels that its defenses were organized in depth. The constraint of time, however, had prevented the Alamo Scouts from landing near enough to the airstrip to verify these reports without potentially alerting the enemy to a specific objective.

The plan of attack was comparatively simple because of the lack of detailed ground reconnaissance, detailed maps, and navigation aids. The Brewer Reconnaissance Force (under Brig. Gen. Chase) would land from destroyers and destroyer transports that could also cover a withdrawal if the defenders were present in strength.

The troops would take only the supplies they could hand carry from the landing craft. This included heavy weapons and ammunition. Medical support was limited to only the cavalry’s organic elements and a portable surgical hospital. There would be no ambulances or field hospitals. Resupply would be by airdrop beginning on D+1—if the cavalry could remain ashore to begin with. If they were successful, they would secure the Momote airstrip and prepare it for improvement by succeeding waves of air force and naval engineers and combat troops. The remainder of Chase’s brigade would land beginning on March 2 or as additional shipping became available.

The Brewer Reconnaissance Force began loading onto the destroyers at noon on February 27 and departed for a staging area that evening in fair weather under occasional light rains. Krueger called a last-minute planning conference before departure. Chase remembered Krueger was “rather pessimistic” and “far from encouraging, a fact which puzzled and worried me.” He warned Chase that Los Negros was heavily defended despite reports to the contrary—presumably even the order directing the attack.

Three LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) with bulk supplies, reinforcing artillery, medical, communications, antiaircraft guns, air forces personnel, and 1st Squadron, 5th Cavalry loaded out at the same time. The weather turned worse by the night of February 28-29. The reconnaissance force (under Chase) and the reinforcements departed the staging base for Los Negros at 4 amon February 29 in heavy rain with about a mile visibility.

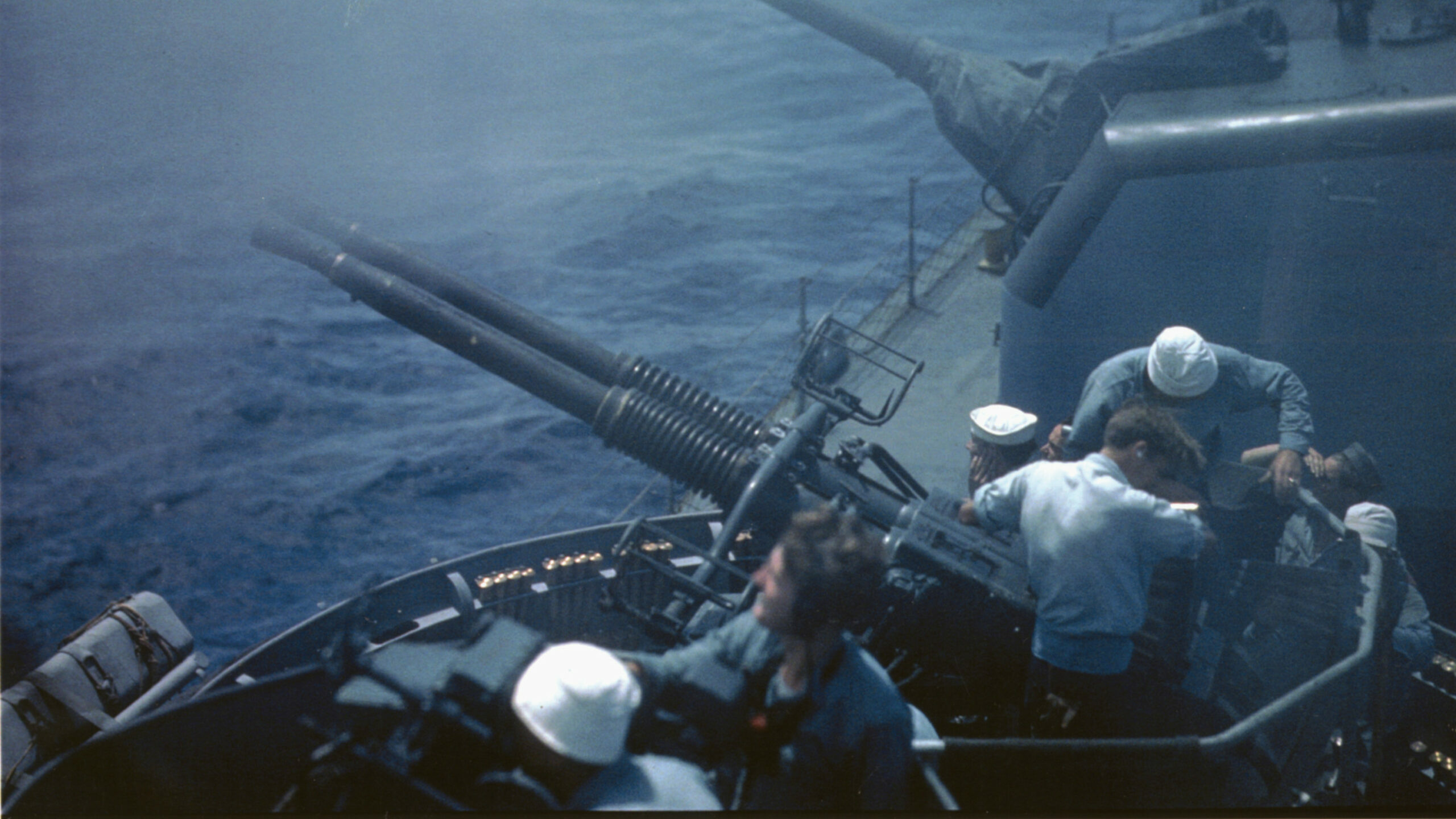

U.S. naval forces, in addition to the destroyers landing the cavalry, included two cruisers and four destroyers to provide gunfire support. Even MacArthur’s naval commander, Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kincaid, appeared concerned enough about the plan to offer more support than the Army originally asked for.

The landing force commander, Rear Admiral William M. Fechteler, ordered the supporting cruisers and destroyers to commence firing at 7:40 am on February 29. The rain and overcast significantly limited the effectiveness of air support. Only three of the 40 Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers scheduled to arrive during the naval bombardment appeared in time to bomb the landing area before the troops came ashore.

All the supporting North American B-25 Mitchell bombers were late in their strafing attack. Pilots saw several coconut “log bomb shelters or pill boxes” on Los Negros and “two serviceable barges” offshore. The Navy reported, “Assault ashore as scheduled. Momote strip and dispersal areas captured as of 0900. Resistance at harbor entrance. Heavy rain.”

MacArthur and Admiral Kincaid watched the landing from the cruiser USS Phoenix; only 138 cavalrymen were in the first wave. Their four landing craft bulled their way through a calm sea almost exactly on schedule. Another wave followed five minutes later.

The enemy was waiting. Japanese 20mm fire slammed into some of the landing craft passing through the narrow entrance to Hyane Harbor, and larger caliber shore-based guns returned the naval salvos. The sailors quickly and accurately returned the fire, silencing several positions.

Second Lieutenant Marvin J. Henshaw of Haskell, Texas, was the first soldier ashore. He led his platoon of Troop G, 5th Cavalry to a coconut plantation where, according to his Distinguished Service Cross citation, he “led the way with great fortitude, determination and courage.”

The enemy opened up with deadly accuracy on the second wave. One destroyer fired on the southern point of land that created Hyane Harbor, but the landing boats had to slow their approach in order for the naval fire to hit the northern point without endangering the assault troops. Wave three was ashore by 9 am, but wave four suffered when the enemy renewed their fire. One of Phoenix’s observation planes strafed some enemy positions with little substantive effect.

A correspondent going ashore with the troops reported, “As we made the turn for the beach, something solid [hit] us. ‘They got one of our guns or something,’ one GI said. There was a splinter the size of a half dollar on the pack of the man in front of me. Up front a hole gaped in the middle of the landing ramp and there were no men where there had been four.” A seaman plugged the hole with his hip, but two GIs and the coxswain died. Staff Sgt. Bobbie K. Horton (Troop H) left a covered position in his boat and manned a machine gun whose operator was dead.

A driving rain soaked the battleground until mid-day. The enemy situation was uncertain as the cavalrymen swept over the Momote airstrip. MacArthur came ashore in mid-afternoon, pinning the DSC on a poncho-clad, rain-soaked Marvin Henshaw and telling Chase to dig in and hang on. “Hold what you have taken, no matter against what odds. You have your teeth in him now don’t let go.”

General Chase had no other choice—if the enemy reacted in force within the next few hours, he could not evacuate his small force with several damaged landing craft. No reinforcements would arrive before March 2.

One report recorded in the 1st Cavalry Division’s intelligence log no doubt concerned Chase, presuming he had the opportunity to see it. Sixth Army reported that same afternoon that “plane crews report slight AA fire” from a mission on nearby Manus Island. There were also flashes from heavy antiaircraft positions in the central coastline of that island.

It was not quite the situation Chase expected, and it may have contributed to his many subsequent and urgent requests for reinforcements, barbed wire, and medical supplies.

Troopers from Lt. Col. William E. Lobit’s 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry (2/5), the core of Brewer Reconnaissance Force, confirmed the Alamo Scouts’ reports. Captured documents indicated at least 200 enemy had been stationed near the airfield.

Concern about Japanese capability to counterattack the small force grew throughout the late afternoon. Lobit and Chase agreed to pull back the line, temporarily ceding the airfield to the enemy. There was no barbed wire, and the two puny 75mm pack howitzers ashore the first day could not safely fire inside the small perimeter.

On the Japanese side, Colonel Yoshio Ezaki, commander of the 51st Transport Regiment, in addition to his own soldiers, had two battalions of infantry (2nd Battalion, 1st Independent Mixed Regiment, and the 1st Battalion, 229th Infantry) at his disposal. He concentrated his forces to defend against an attack from the north and did not expect the Americans to land in the south in Hyane Harbor because the narrow entrance would subject an attacker to shore fire from both flanks.

When the Americans landed, Ezaki’s superior, General Hitoshi Imamura, commander of the 8th Area Army, ordered an immediate counterattack with all his forces. Evidently concerned about security even at the time when the invading Americans were most vulnerable, he ordered his men “neither to fire nor move about in daylight.” He directed only the 1st Battalion, 229th, commanded by a Captain Baba, to drive the Americans out.

Ezaki exhorted his men to “charge desperately into the enemy and by obtaining their provisions, continue fighting. When you suffer several losses or become isolated and enveloped by the enemy, in no case will you retreat without orders. No one will retreat of his own accord. Although to fight until the last man and to commit suicide are similar in form, they are entirely opposite in spirit. The officers and men of the Garrison Unit must fight with the intention that each one will kill 10 of the enemy.”

Ezaki’s report of the invasion to Imamura stated simply, “At 0430 the enemy began landing operations on the south shore of Hyane Airfield. Prior to this, they bombarded and strafed from warships. The Hyane Sector Unit (1st Battalion of the 229th Infantry Regiment) [is] now engaged in combat with them.”

He added, “With the arrival of morning, the enemy naval bombardment continues. The officers and men will fight furiously against the enemy landing and destroy them. We are in the midst of preparing for future movement. We pray for a successful battle.”

Ezaki ordered Captain Baba to counterattack the Americans that night. “Be resolute to sacrifice your life for the Emperor.”

As night fell on February 29, small groups of Japanese tested the Americans by crawling in close enough to throw grenades. GIs could see the enemy only when a grenade exploded or when they got to within literally a yard or two of their foxholes.

Private Walter E. Hawks of Troop C killed several Japanese with his BAR, holding his fire until they were less than 20 feet from his foxhole. A few Japanese penetrated Troop E’s line and isolated a platoon. Most of the wounded had to lie in their foxholes until daylight; a few bled to death. The handful of doctors with the 30th Portable Surgical Hospital worked under flashlights and lanterns on the wounded who could get back.

Chase’s S-2, Major Julio Chiaramonte, cut down two of the enemy just yards from the headquarters. Pfc. Allan M. Holliday and Corporal James E. Stumfoll threw several grenades into a bunker, and the enemy threw two of them back. Other GIs killed a survivor and blew in the roof with TNT and grenades. As daylight on March 1 approached, the cavalrymen found 66 enemy dead inside the small perimeter. Seven Americans were dead and six were wounded.

Lobit’s troops patrolled constantly that day until about 4 pmas enemy pressure increased by the hour. Chase ordered the perimeter tightened even more. Naval guns and cavalry mortars were busy all day, and another air strike came in as the patrolling ended. Ground troops suffered some friendly fire casualties.

Captain Baba led a group of infiltrators who were stopped about 30 yards from Chase’s command post. Major Chiramonte led four men into the thick underbrush as the sounds of grenade explosions picked up—the enemy was committing hara kiri. Captain Baba was among the dead.

While there was no large-scale attack on the night of March 1-2, 50 enemy landed behind the Americans (whose backs were to Hyane Harbor) and had to be hunted down. By the morning of March 2, there were 147 known enemy dead inside the cavalry’s line.

The division operations journal recorded the following message at 2:10 am on March 1: “Need more Med supplies. Drop Plasma.” Other messages reflected an air of urgency, though probably not desperation. The Sixth Army liaison officer reported on the afternoon of March 2, “Chase requests additional Regt to cope with increasing enemy resistance.”

As evening fell, Chase reported increasing resistance. “Requests other Regt. Our losses light.” General Swift, the commander of the 1st Cavalry Division, forwarded the request to Sixth Army. One officer reported, “[advanced] echelon beachhead still under mortar fire…. Rather warm here. Major King killed, Lt. Savage wounded.” Reinforcements were already landing.

Thursday, March 2 saw the arrival of the LSTs carrying 1/5 Cavalry, the rest of the 9th Field Artillery Battalion, the 40th Naval Construction Battalion (“Seabees”), and the 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment. The Seabees brought a ditch digger to construct a 300-yard-long trench which they protected with automatic weapons and rifles. They also used their bulldozers to clear fields of fire. GIs recaptured the airfield that afternoon.

Intelligence reports indicated the Japanese had about 1,000 men in the airfield area, with reserves on Manus and elsewhere on Los Negros numbering about 2,000. As the Americans built up their small force, the Japanese still dictated the time and place of counterattacks.

The inexperienced Americans also failed to get all of their supplies ashore. They did not put enough men to the task of unloading before it was time for the landing boats and LSTs to put to sea for the night.

Chase went to Krueger directly the next morning asking for the immediate return of the LSTs and landing of the remainder of the 529th Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment. Krueger forwarded the message to MacArthur in the early afternoon.

Colonel Ezaki, meanwhile, either failed to understand the situation facing him or chose to misrepresent it to his higher headquarters. Throughout March 1 he thought his troops had halted American operations. He did not believe the situation around Hyane Harbor was serious, and he did not know the actual strength of his own 1st Battalion, 229th Infantry. His main concern was apparently the U.S. naval bombardment of his own headquarters at a plantation on Los Negros. It was March 2 before he reported to 8th Area Army that the Americans had occupied the air strip.

He tried again to organize an attack on the night of March 2-3, and orders went out to the units in the vicinity to concentrate at the settlement of Lorengau. Plans were drawn up for the Iwakami Battalion to hit the Americans from along the Salami-Hyane road, while a rifle company would cross the Porlaka Channel to hit the airstrip from the west.

But it was too difficult to coordinate the multiple troop movements, and Ezaki delayed the operation until the night of March 3-4. The Iwakami Battalion made the main effort, attacking south from the vicinity of a skidway north of the airfield used by locals to carry their boats across a narrow piece of land on Los Negros. Ezaki reported the breach of the American perimeter; he said his men “broke through the enemy’s first line of defense but [were] unable to advance after attacking the second line. The Iwakami Battalion, which is the Salami Sector Unit, was led by the battalion commander in person and penetrated the northern sector of the airfield.”

Probing attacks hit the American positions shortly before 8:30 pm. About 30 minutes later, two yellow flares shot up and a company-sized attack hit 1/5 Cavalry. Several hundred enemy also drove into 2/5, particularly against Troop G on the north side of the airstrip. They set off most of the American mines but despite the losses “kept on coming,” according to a historian. They made no effort to infiltrate or use cover.

Several cavalrymen reported hearing the enemy talk and even sing as the GI fire literally cut them apart. Yet a few of the enemy managed to get through the foxhole line and cut telephone lines leading from the foxholes to the platoon and company command posts. The platoon leaders, Lieutenants Winn M. Jackson, Jack P. Callighan, Jr., and Marvin Henshaw, had no communications with the troop commander and told their men to stay put and “fire at anything that moved.” This included Japanese soldiers armed only with knives and grenades.

Colonel Lobit organized a counterattack, restoring the line before daylight on March 4. Accurate artillery and mortar fire also played a decisive role in stopping the attack. The American casualty reports are telling, though, as the troop on March 2-3 lost one man killed, but 15 dead in the March 3-4 attack.

Troop G counted 168 enemy dead around its foxholes, most of whom were around the position of squad leader Sergeant Troy A. McGill, who received a Medal of Honor for ordering his surviving men to another position while he singlehandedly held off the enemy. Sergeant McGill’s machine gun “became the object the most desperate enemy assaults.” He stayed in action throughout the night, personally accounting for an undetermined number of enemy. He stayed in action throughout the night, personally accounting for 105 enemy dead, but lost his life in the process.

Corporal James M. Madden, Troop H, died while crawling through enemy fire to retrieve a machine gun and return it to action. Staff Sgt. Stephen A. Lowery ran through friendly and enemy fire to rescue a GI suffering from shock. It was clearly a small unit fight to the death.

Some attacks, however, were ineffective and uncoordinated. One group reportedly moved along a road while singing “Deep in the Heart of Texas” as the defenders’ bullets tore into them. Shortly before daylight, a Japanese officer and about a dozen of his men walked into the open, where they killed themselves with their grenades. While the attacks against Troops E and F were not as powerful as the one that hit Troop G, the enemy infiltrated toward the CPs and mortar positions. Five enemy set up a mortar on the top of Lobit’s CP.

Likely by tapping phone lines, the Japanese learned the names of some American officers. One mortar platoon leader received a message using his name and ordered his men to retreat from their firing positions. This took it out of action for hours.

Late on the night of March 3-4, another message believed to be false led an antiaircraft artillery battalion to move its CP. During the height of the enemy attack in the vicinity of the skidway north of the airfield, English-speaking Japanese troops tapped the wire line of one battery to its forward observer and sent confusing orders. The Americans used their less reliable radios for the rest of the night.

The Seabees provided invaluable support by passing ammunition forward and, as daylight approached, by taking positions in foxholes when needed. One group kept infiltrators from overrunning a machine-gun position on the beach.

Chase had put every available man in the line, foregoing reserves to prevent infiltration. The 81mm mortars were massed near the center of the perimeter, while all the 60mm mortars were moved close to the front line. Destroyers took areas of likely enemy troop concentration under fire.

After a new line was established early on March 4, more than 750 enemy dead were recovered in front of the cavalry’s positions and later buried. The Yanks took no prisoners.

American casualties on March 4 totaled 61 dead and 244 wounded, including nine Seabees killed and 38 wounded. The 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry received a unit citation for its performance.

Attacks continued, and Chase continued to make unsuccessful requests for barbed wire to help prevent infiltration. A March 5 airdrop brought 100 cases of carbine ammunition and 1,000 rounds of 90mm antiaircraft ammunition (also effective against ground targets).

On March 5, the Americans resupplied, distributed ammunition, and improved their defenses. Reinforcements continued to land. A letter written by a Japanese officer on March 6 revealed that animosities and lack of cooperation between units were partially responsible for the desperate situation in which Colonel Ezaki found himself.

This officer was “indignant about the enemy’s arrogant attitude,” but he also wrote, “The main force of the enemy which came to Hyane Harbor, north point area, landed successfully because [the] Iwakami Battalion commander employed such conservative measures,” and the battalion commander and Captain Baba would not cooperate. The letter also suggests that Ezaki was either out of touch with the situation or incapable of coordinating the actions of his subordinates.

If the attacks were not well coordinated or well planned, nonetheless the Japanese displayed a capability for hard fighting. Many service troops took part in the big night attack, using bayonets attached to five-foot poles. One American report noted that some enemy soldiers were found with makeshift tourniquets near pressure points, apparently positioned to be ready for use in case of a serious wound. The Americans assumed that the enemy would simply tighten the band and continue to fight until overcome by loss of blood.

The lessened intensity of the night attacks and the mounting toll of Japanese dead after March 4 indicated that the beachhead on Los Negros need not fear another coordinated Japanese counterattack.

On March 6, the 5th Cavalry was reinforced by the 12th Cavalry arriving from New Guinea, along with the 271st Field Artillery Battalion. On that same day, the first American plane landed on the Seabees-repaired Momote air field. Over the course of the next few days, more men and supplies arrived at Los Negros, ensuring the doom of the Japanese.

Much hard fighting took place until May 18, when several more islands (Manus, Hauwei, Korunist, Ndrilo, and Rambuto) were secured and the Admiralty Islands campaign was officially declared ended. The action had cost the 1st Cavalry Division 290 troopers dead and nearly 1,000 wounded.

But the Japanese had paid a heavier price: 3,317 dead and only a handful captured. More importantly, the seizure of the Admiralties opened the door for MacArthur’s march northward. And the victory proved that the greenhorn cavalrymen were as tough and heroic as any veteran outfit, and were well prepared for the combat that still lay ahead: the invasion of Leyte.

My father Ward Abell was a Sgt in the 1st.Cavalry.

He also was in the first wave on Los Negros Island.