By David H. Lippman

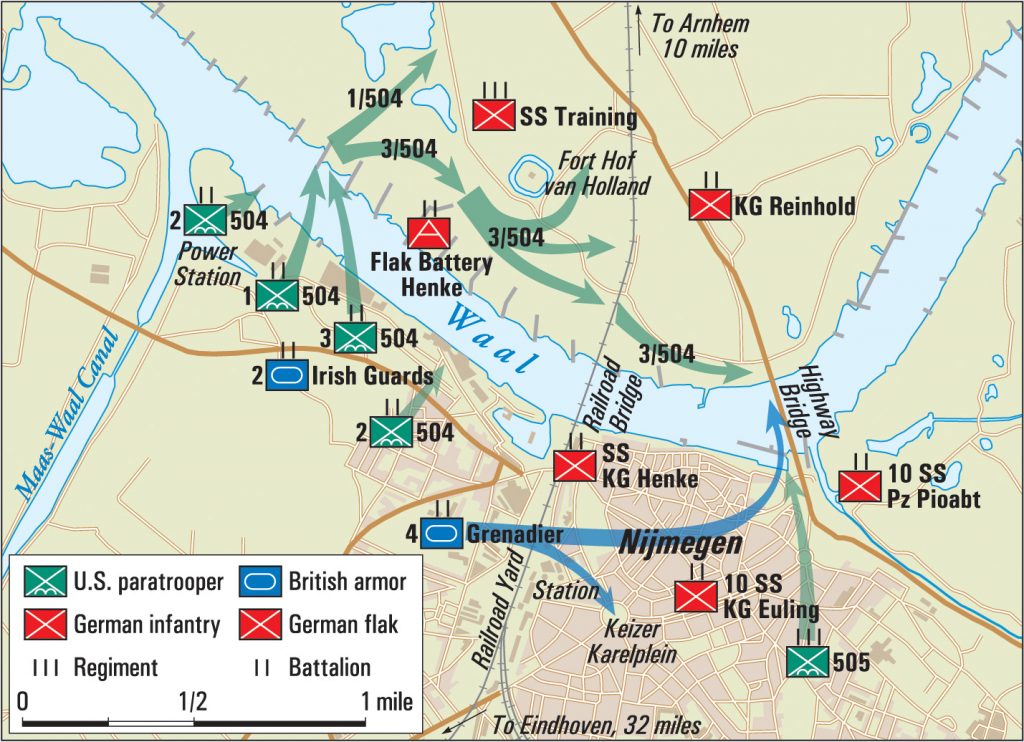

Major Julian A. Cook stood on the ninth floor of a power plant west of the Dutch city of Nijmegen and stared north across the 400 yards of the fast-moving Waal River at German defensive positions on the other side—the square turn-of-the-century Dutch Fort Hof van Holland, its machine-gun emplacements, 20mm guns, and dug-in troopers of the 10th SS Panzer Division.

Cook’s 3rd Battalion of the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division’s 504th Parachute Regiment had been ordered to send two companies across the Waal by assault boat to seize the Nijmegen rail and highway bridges that crossed the river east of the fort. A 27-year-old Vermont native, graduate of the West Point Class of 1940, and seasoned combat veteran, Cook thought, “Somebody has come up with a real nightmare.”

Cook’s incredible mission was intended to enable the British Guards Armoured Division to advance across the bridges and drive north to Arnhem to relieve the battered British 1st Airborne Division, which was clinging to precarious bridgeheads north of the Neder Rijn River, particularly at the Arnhem Bridge.

Possession of that would enable the British to drive west and silence the V-2 rocket sites in The Netherlands, and east into Germany to seize the Ruhr and its factories. Doing so would be the climax of Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery’s Operation Market-Garden, his most audacious plan and the largest airborne operation in history to that time—a 63-mile airborne carpet laid through German lines by more than three airborne divisions.

The problem was that three days since the September 17 opening airdrop and assault, Operation Market-Garden was going fearfully wrong. Monty’s plan had depended on his paratroops and tankers gaining ground and achieving objectives with surprise against limited opposition. The two American and one British division had landed far from their objectives and found two SS panzer divisions holding them. Advancing British tanks were delayed when German engineers blew key bridges. Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks’ 30th Corps, leading the ground attack, battled up one main road, called “Club Route” by his men and “Hell’s Highway” by American paratroopers.

One major problem the Allied advance faced was the 1st Airborne Division’s isolation at the top of the corridor. Cut off from 30 Corps and its support, they relied on supply airdrops that were not getting through because the Germans had overrun the drop zones—most of the supplies were landing in German hands. The Polish Parachute Brigade, expected to reinforce 1st Airborne, had been socked in by bad weather and fog in England, as had supply drops. Worse, paratroopers were not equipped to tackle the armored vehicles of the 9th SS Panzer Division.

At Nijmegen, the situation was different, but just as bad. The 82nd Airborne Division, under 37-year-old Brig. Gen. James “Jumping Jim” Gavin, the youngest division commander in the U.S. Army, was east of both Nijmegen and the heavily wooded Groesbeek Heights. His orders from British 1st Airborne Corps commander Lt. Gen. Frederick A. “Boy” Browning were to seize the heights first and then the highway and rail bridges at Nijmegen.

Once Gavin’s two parachute regiments landing east of the heights were on the ground, they moved to take the heights and then move on into Nijmegen. There they found the 10th SS Panzer Division had beaten them into the city and entrenched around the bridges. Meanwhile, German troops emerged from the Reichswald, attacking Gavin’s positions on the Groesbeek Heights. Ferocious fighting ensued, as Gavin’s “fugitives from the law of averages” struggled to retain control of the heights and their supply drop zones.

The 82nd’s isolation issues became moot on September 19, when the lead elements of the British Guards Armoured Division arrived after their delays, providing additional infantry and tanks for attacks in Nijmegen. But the fact remained that the Germans were holding both sides of a 400-yard-long highway bridge with some of the best-trained and equipped men in their inventory: the 10th SS Frundsberg Division, under SS Brigadefuehrer Heinz Harmel, who combined his battle-hardened men with the various training, antiaircraft, and garrison units in the city to create a formidable force with typical German flexibility. Harmel reported to SS Gruppenfuehrer Wilhelm Bittrich, commander of 2nd SS Panzer Corps, and above him, 1st Parachute Army Lt. Gen. Kurt Student. Over him was the commander of Army Group B, Field Marshal Walther Model, a stocky, coarse, monocled officer, whose headquarters at Arnhem had nearly been seized by British paratroopers on September 17.

Believing that the hodgepodge of reinforcements he was receiving would be able to launch a massive counterattack against the British and Americans, Model refused to blow the major road bridges on Club Route, intending to use them for the assault. These included the two structures at Nijmegen. Determined to eradicate the enemy assault, Model gave Student a terse order for the 20th: “Wipe out the Allied airborne force!”

Now Model’s obstinacy backfired upon him. Battling Germans and a cracked spine suffered in his parachute jump, Gavin was determined to seize his two bridges. “If I did nothing but pour infantry and British armor into our end of the bridge,” Gavin wrote later, “we could be fighting there for days and (1st Airborne) would be lost.”

Gavin met with Horrocks and Browning on the 19th, and Browning—who had founded and commanded the 1st Airborne—firmly said, “The Nijmegen Bridge must be taken today. At the latest, tomorrow.”

Gavin, Horrocks, and Browning discussed what to do, with Horrocks saying, “Jim, never try to fight an entire corps off of one road.” All of his vehicles were snarled in bumper-to-bumper traffic for miles.

Nonetheless, Gavin presented his colleagues with a simple but audacious plan. The best way to take a bridge was from both ends at the same time. He would team up one of his best battalions, Lt. Col. Benjamin Vandervoort’s 2nd Battalion of the 505th Parachute Infantry, with the tanks of Lt. Col. J.N.R. Moore’s 2nd Battalion of the Grenadier Guards and motorized infantry of Lt. Col. Edward Goulburn’s 1st Grenadier Guards to drive north and onto the bridge. All three were veteran units. Vandervoort and his men had freed the first town in France to be liberated on D-Day, Ste. Mere-Eglise, while the Grenadier Guards had driven from Caen to Nijmegen.

These forces would make up the “holding attack” to pin down the German defenders in best American Fort Benning fashion, while the main assault would be launched by two companies of Cook’s 3rd/504th, H and I, who would storm across the Waal River in assault boats, covered by smoke and steel from British and American artillery and tank fire by Lt. Col. Giles Vandeleur’s 2nd Irish Guards. The 504th were no slouches, either. While missing D-Day, they had fought in Sicily and Italy.

Gavin wanted a pre-dawn assault on September 20. But now Horrocks’ traffic jams let him down. Although the British general ordered his boats, further down in the column, brought forward immediately, they made slow progress at the hands of German shelling of Club Route. The assault crossing was delayed from pre-dawn, to 8 am, then to 11 am, and then to 1:30 pm.

Meanwhile, Vandervoort and the Grenadier Guards moved to seize the densely-populated city of Nijmegen, home to 100,000 people, most taking cover from shellfire, except for one: an elderly lady who emerged from her residence to tell the advancing Americans that she had been hiding a shot-down RAF flyer for months in her cellar.

After freeing the aviator, Vandervoort sent in his E and F Companies abreast with tanks, mortar, and artillery fire, against German strongpoints, anti-tank guns, and machine-gun nests. Vandervoort’s men, formed into 13-man squads, battled 88mm anti-tank guns perfectly placed to fight off tanks and infantry, as well as about 500 fanatical SS grenadiers. American troops stormed into the top floors of buildings so they could direct machine-gun fire on German positions below. Other paratroopers hurled hand grenades through windows, kicked in doors, and cleared defended houses in room-to-room fighting.

Guards tanks added to the din and destruction with fire from their own 76mm guns and .30- and .50-caliber machine guns, spraying houses under attack.

Vandervoort was impressed by how his paratroopers and the Guardsmen worked so well together. Even so, the struggle was harsh. D Company’s executive officer, Lt. Waverly Wray, who had always led by example and from the front since D-Day, did just that, taking a Bazooka team—including three officers—around the flank of some defending German tanks and through a rail yard; he was killed in the struggle. But his sacrifice enabled D Company, despite heavy casualties, to storm across the rail yard and attack dug-in German positions.

Meanwhile, Cook’s two companies waited helplessly under cover for the boats to arrive. The attack had been postponed once again, to 3 pm. When Gavin briefed Cook on the plan, the angry major said, “Well, General, if you wanted men on the north bank of the river, it would have been very simple to have dropped them in the beginning.” Cook, however, did not know that Gavin had considered that very possibility but was afraid of losing an entire infantry battalion if he had done so.

Now, as the 505th and the Guards struggled through Nijmegen, the 504th waited for the boats.

Cook’s two companies prepared to cross the fast-flowing Waal at a point between Nijmegen’s electrical power plant and the Nyma silk factory. They wondered when the boats would arrive, how many, and what they were made of.

Only the British knew it, but the boats were coming, the trucks carrying them avoiding German shelling, which blasted open one truck, cutting their numbers from 33 to 26.

Meanwhile, Cook’s men peered through their binoculars or climbed the power plant to peruse the enemy before them. Staff Sgt. Robert Tallon, the battalion operations sergeant, rode the plant’s elevator to the top and it became stuck. When he got it moving, he leaped off at the first available floor and jogged up to the roof. “I could pick out several camouflaged German emplacements,” he said later. “It was an eerie feeling. I kept thinking over and over, ‘This is suicide. This is just plain suicide.’”

The British tankers supporting the assault were worried, too, even though they didn’t have to actually cross the river. Major Edward G. Tyler of the Irish Guards asked the 504th’s C.O., cigar-chomping Colonel Reuben Tucker, if his men had ever practiced this type of operation before. “No,” replied Tucker laconically. “They’re getting on-the-job training.”

H and I Companies would lead the assault, H on the right, I on the left. I Company, under Captain T. Moffatt Burriss, would set up a left flank position. H Company would skirt around the German defenses and take the north end of the Nijmegen Bridge. The 2nd and 1st Battalions would follow to establish the rest of the bridgehead and take the less valuable rail bridge.

Now the British and American forces moved into position, even though the boats still hadn’t arrived. The 82nd’s 307th Engineer Regiment sent in detachments to row the boats.

The American paratroopers nervously awaited the boats while staring at the wide and fast-moving river, all deathly quiet. Captain Delbert Kuehl, the 504th’s Protestant chaplain, insisted on crossing with the first wave. Other men showed their nervousness. Lieutenant Harry Busby took out a Camel cigarette, lit it with his valuable Zippo lighter, and tossed both the pack and cigarettes away, saying he would “have no need of them no more.” He was right. An hour later he would be dead.

To relieve the tension, Cook told his men: “I’m going to stand in the prow of the boat like George Washington crossing the Delaware. Then I’ll clench my fist, push it forward, and yell, ‘Onward, men, onward!’”

Now, 15 minutes before H-Hour, the British trucks finally arrived. They were seven hours late. The paratroopers stormed the trucks to unload them.

The 2nd Irish Guards Sherman tanks lined up on the Waal’s shore and started pasting the Germans with high explosives. British and Canadian rocket-equipped Hawker Typhoon dive bombers pounded German defenses. American artillery fire from the 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion and British guns from the 153rd Field Regiment added to the din and destruction.

Opening the trucks and unfolding the boats, the paratroopers were shocked. Lieutenant John Holabird recalled, “The boats were flat-bottom, with low canvas covered sides and bottoms. They looked pretty flimsy to me. But they were heavy; they had to be to carried by 16 men. We unloaded the boats off the trucks that brought them up and set them on the ground.”

Each boat was 19 feet long with a flat, reinforced plywood bottom. The canvas sides measured 30 inches from floor to gunwales and were held in place by wooden pegs. The paratroopers took wooden staves attached to the plywood bottoms, swiveled them up, and secured the canvas sides to the staves. The flimsy appearance of these would-be assault craft stunned the paratroopers. Chaplain Kuehl asked the engineers how the boats were propelled. The answer was: canoe paddles. Loaded with helmets, rifles, grenades, and ammunition, the paratroopers lugged the boats down to the riverbank. Each one would carry 13 troopers. They had 20 minutes to prepare for the assault.

Captain Henry Baldwin Keep was called the “battalion millionaire” for being part of the Biddle banking and law family, but he was an 18-month combat veteran. He waited by his boat for the signal to go, watching dive bombers swoop down. The smoke screen didn’t look very effective to him. “Suddenly a whistle was blown. It was H-Hour. Each boatload hoisted their boat onto their shoulders and staggered out across the flat top of the bank. Our job had begun,” he recalled. Jammed in their boats, 520 paratroopers started paddling across the Waal.

At that moment, the machine-gun platoon of 2nd Battalion’s HQ Company opened fire with their deadly .50-caliber Brownings, trying to keep the Germans’ heads down. Major Cook led his men and their boats over the river’s dike and into the drink. As soon as the boats hit the water and the men started paddling, the Germans realized what was going on and opened fire with every weapon they had. It was 100 yards from the top of the three-foot-high dike to the river’s edge, which gave the Germans a rich shooting gallery, even before Cook’s men were afloat.

British smoke shells were heavy and effective, but so were German guns, which had the enfilade advantage over the advancing American boats. The Germans began to find the range and brought down plunging mortar fire and high-velocity shells on Cook’s boats.

The leader of this desperate assault, Major Cook, kept on rowing, praying out loud to maintain a stroke and cadence: “Hail Mary—full of Grace—Hail Mary—full of Grace,” over and over again. Chaplain Kuehl said over and over again, “Lord, Thy Will be done.” Captain Keep tried to remember his numbers from crewing days at Princeton, but wound up nervously counting: “7-6-7-7-7-8-9.”

On shore, Horrocks, Browning, and Colonel J.O.E. Vandeleur—Giles’s cousin—who commanded the Guards Armored Division’s “Irish Group,” watched in silence. “It was a horrible, horrible sight. Boats were literally blown out of the water. Huge geysers shot up as shells hit and small-arms fire from the northern bank made the river look like a seething cauldron,” Vandeleur recalled. The tanks were at risk, too, out in the open, perfect targets for German anti-tank guns. “We were wide open,” Irish Guards Major Edward Tyler recalled, “16 tanks silhouetted against the skyline.”

A brisk wind ripped apart the 2nd Irish Guards’ smoke screen, and the tankers were now running short of every type of ammunition. Giles Vandeleur remembered almost “trying to will the Americans to go faster. It was obvious that these young paratroopers were inexperienced in handling assault boats, which are not the easiest things to maneuver. They were zigzagging all over the water.”

Despite their heavy weight in fire, the Allied attack caught the Germans flat-footed. The defenders were static troops cobbled together from Wehrmacht, SS, and Luftwaffe units—20mm antiaircraft guns and gunners, labor units, and garrison and training units. They had to rely on their existing, pre-built fortifications. Furthermore, German operational doctrine ruled that an assault river crossing required days, even weeks, of planning. The defenders were not prepared for how swiftly the Americans and British could improvise such a well-coordinated attack.

Now the 3rd/504th, despite heavy casualties, did what they set out to do. They neared the far shore and started leaping out of their boats onto dry ground to attack. Enraged paratroopers wasted no time hurling grenades at German machine-gun nests. One Landser (the German name for their troops) tried to throw one back but didn’t know it was point-detonating. The grenade’s explosion merely cleared a path for the advancing Americans.

Furious paratroopers stormed out of their boats, unslung their rifles, and charged up the north bank of the Waal, bayonets fixed. Sgt. George Leoleis of I Company led his men to attack a machine-gun nest at close range, knocking it out with hand grenades “and some trench knife handiwork.” The surviving Germans fled, but Leoleis and his men chased them. Pfc. James Ward of Company H also struggled to get ashore, exhausted from the crossing, having done so with his rifle butt like everyone else in the boat. He shouted for other men to get off the beach and joined them.

Despite horrific losses and murderous fire, the Americans maintained their assault. They were temporarily devoid of unit organization; some were still shocked or even seasick from the river crossing, but all were superior to the equally disorganized defenders, which ranged from 15-year-old Hitler Youth to 60-year-old Volkssturm men. Lieutenant Megellas led his H Company troopers in a rough skirmish line, across 500 yards of flat, open terrain to reach their objective, a dike. The Germans raked it with small-arms fire. “Since there was no place to take cover, our only alternative was to charge in the face of this murderous fire and rout the enemy from their positions,” he said later. Pfc. Walter Muszynki showed ample determination and courage by firing his .30-caliber light machine gun from the hip.

Across the Waal, British and American senior officers watched the heroism and horror through their binoculars and field glasses. Lt. Col. Vandeleur “saw one or two boats hit the beaches, followed by three or four others. The men got out and began moving across an open field. My God! What a courageous sight it was!”

On the north bank, medics struggled to care for wounded men. Their Red Cross armbands were little protection against distant German mortar fire. “The medics were the bravest men there, running around trying to help everybody,” said Pfc. Herbert P. Keith, a wounded engineer. “I laid three hours before being picked up and taken to a first-aid station.”

The paratroopers also paid tribute to the engineers who assembled, coxswained, and paddled the boats. “Most of us did get to the other side,” said Pfc. Walter E. Hughes, “thanks to the efforts of some very brave engineers, who to me were the real heroes that day.”

One of them was Staff Sgt. Warren G. Hayes, of Company C, 307th Airborne Engineers, who suffered a painful leg wound. Even so, he took command of the remaining infantrymen and got the boat to the north bank. There, he jumped out of the boat and pulled it ashore to save the wounded from drowning, all while under fire. That done, he organized a new crew to head back and pick up another boatload of troopers. He refused evacuation, making six round trips in all, and later received a Silver Star.

Only 13 of the 26 boats reached the north bank, but as soon as they did, the surviving engineers rowed back in those that could still float to pick up more men, bringing back the wounded. Technician 5th Grade Harry W. Nicholson of the 307th Engineers, badly wounded in the thigh, was so grateful to make it back to the south bank, he gave Private Ollie B. “Obie” Wickersham his trench knife with brass knuckles. Despite being hit in the hand by 20mm shrapnel, Wickersham made three round trips across the river that afternoon.

Even the Dutch Underground got involved. Pfc. Leonard Trimble was one of the wounded troopers brought back. He struggled to rise but slipped on the boat’s plywood bottom. He saw three men rushing toward him through shrapnel. “There was never a more welcome sight in my life as these men approached me with their orange armbands, indicating they were Dutch Underground. They took me back to the nearest aid station,” he said. Ambulances took the wounded Americans to Nijmegen army and civilian hospitals. The latter had dedicated nuns and girls working but lacked heat and electricity. Both were overwhelmed with wounded men—many died awaiting surgery.

On the north bank, 3rd Battalion was moving fast, deploying skirmishers against German guns 800 yards away, firing their Browning Automatic Rifles, machine guns, and rifles from the hip, and receiving support from Vandeleur’s tank fire.

“Their constant overhead fire into the embankment where the Germans were ensconced was heavy and effective,” said Captain Keep, the 3rd Battalion S-3. Lieutenant Edward Sims organized survivors of his Company H boat and another boat. A combined group of 18 men led a frontal assault on the dike, using rapid fire to overcome German weaponry. “Enemy fire was heavy,” Sims said, “but the men with me did not falter. Their courage and determination was [sic] obvious.”

On the left, Burriss’s I Company stormed the 15-foot-high rail embankment, facing a harsh German machine-gun crossfire. Lt. Robert Blankenship saw one of them firing into I Company’s left flank, so he moved across 100 yards of open ground, drawing the MG42’s fire. He closed to within 50 yards and emptied his M-1 rifle’s eight-round clip, killing the four-man crew. Then a German sniper five yards away shot at him. Blankenship lunged at the sniper with his fists and knocked him unconscious.

Lieutenant Burriss told his men to use their grenades in one mass attack, and they did, hurling them over the dike. “The earth underneath us trembled with the almost simultaneous explosions,” he wrote later. “Then there was a moment of silence in front, followed by the screams of wounded Krauts. All along the line, other Germans stood up, ready to surrender.

“But it was too late. Our men, in frenzy over the wholesale slaughter of their buddies, continued to fire until every German on the dike lay dead or dying.”

Under close-range pressure, the Germans got the point. Some began to flee their dugouts. Lt. Megellas was bandaging Sergeant Marvin Hirsch’s arm when Sergeant William H. White of I Company yelled, “There go the SOBs—after them, men.” Megellas approved the initiative, and White and his pals charged after the Germans.

“Our plan to reassemble at this point obviously went astray,” Megellas wrote, “but I believe Sgt. White’s ingenuity served to our advantage, since the enemy was not given an opportunity to regroup at alternative defensive positions.” The men stormed a road, which was defended by the usual German combination of dugouts and machine guns. When the dike was overrun, Megellas assembled men to take the ancient square-shaped Fort Hof van Holland. Noting his losses on the way over, he thought, “It’s payback time.”

Megellas divided his force into two groups, one moving up the dike road while Megellas would follow just north of the road and meet him where the railroad and dike road intersected.

Simultaneously, Lieutenant Holabird and his engineers closed in on the railroad bridge, determined to prevent the Germans from sending it into the Waal River in a blast of explosives. They came up against two German pillboxes and attacked them from the sides, hurling grenades into their hatches to kill every one in them.

Major Cook and Captain Keep took 30 men across fields and ditches in squad rushes, racing for the Nijmegen road bridge.

The 504th had its bridgehead across the Waal, paying an enormous price for it. Now the paratroopers, American flag patches sewn on their sleeves, would finish their job, which would require neutralizing Fort Hof van Holland. Companies H and I now fought their way along the railroad embankment toward the rail bridge. Company I stormed toward the east side of the bridge, Company H the west side. The Germans hit back with the usual machine-gun fire, hitting D-Day veteran Pfc. John Rigapoulos of Company H’s 2nd Platoon in the chest, killing him. His furious buddies charged the German positions and foxholes and opened fire on the fort.

The fort stood between the northern abutments of the rail and road bridges, and the Americans attacked. Lieutenant Edward W. Kennedy’s 3rd Platoon of I Company moved along a ditch parallel to the railroad embankment within 20 yards of the trestle. There, Sergeant Theodore Finkbeiner peered over the top of the embankment and found himself face-to-face with a German soldier and his MP34 submachine-gun, the legendary, deadly, and highly-prized (if captured) “Schmeisser.”

“I think he was surprised as I was,” Finkbeiner said later. “I ducked, but the muzzle blast blew the little wool cap off my head. My two companions and I tossed some grenades over the embankment, and the German tossed some over at us. I heard what I assumed was a command, and several Germans charged us. We repulsed the charge, killing a couple and wounding another.”

Another determined American was less lucky. Sergeant William Kero of the 307th Engineers rushed to the top of the embankment and sprayed the Germans with Thompson submachine-gun fire. Kero himself was cut down, earning a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross.

More American courage and determination were shown in the struggle to seize Fort Hof van Holland. Staff Sgts. James Allen and Leoleis rushed a house five yards from the railroad overpass and motioned for Pfcs. Muszynski and Ternosky to bring up their light machine gun. As they did, 30 Germans behind them opened fire, joined by a mobile 20mm flak gun. Their bullets killed Allen and wrecked the machine gun, but Muszynski broke out hand grenades, using them to knock out the flak gun and kill German troops, before he was also killed. The other two paratroopers withdrew. Muszynski was awarded a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross.

More Company H men turned up, supporting Finkbeiner, decimating Germans, and moving under the rail bridge’s trestle approaches to the other side of the embankment. With that, Fort Hof van Holland was now surrounded by 3rd/504th men, determined to put the position and its 20mm guns and machine guns out of action. Megellas “directed all the fire we could mass at those targets, forcing the Germans to take cover,” he said later.

As the Germans did so, Sergeant Leroy Richmond took off most of his equipment, swam across the fort’s antique moat, climbed its earthen wall, and started waving his arms, pointing to the Germans inside. He signaled to Megellas and his crew to circle around to a drawbridge that was the only way into the fort. Then Richmond got shot.

“Sergeant Richmond must have been carrying a rabbit’s foot,” Megellas wrote later. “The bullet grazed his back, but did not seriously wound him. He started back down the incline, swam the moat, and rejoined us. From our position on the edge of the moat, we lobbed hand grenades over the parapet and inside the fort.”

Megellas and 11 of his men worked their way around the fort to the causeway on the south side. Then he, Pfc. Robert Hawn, and another trooper rushed across the causeway, reaching the archway. German troops shot back with rifles and hurled hand grenades. Undeterred, the Americans hurled Gammon grenades into the German positions, while Sergeant Robert Seymour called upon the Nazi garrison to surrender. He was wounded by a sniper for his trouble. To make matters worse, the 82nd’s own artillery regiment, the 376th, started shelling the fort with its pack 75mm howitzers, subjecting Megellas’ band to “friendly fire.”

Megellas decided to move his men to a position north of the fort. “I didn’t know how many Germans were inside the fort, but as long as they didn’t constitute a threat to our forces still crossing the river or impede the attack on the bridges, I was not concerned. We could move out to help seize the bridges, our principal objective, and let the men of the 1st Battalion coming up behind us take care of them,” he wrote.

Company H was storming down the west side of the embankment, Captain Carl Kappel’s men battling flak and machine guns and exchanging grenades with the Germans. A group of Dutch civilians took shelter under the railway embankment. Some Americans found the shelter, thought it was a passageway, and heard German-sounding voices. They hurled Gammon grenades and wounded two Dutch women.

One of Kappel’s squad leaders, Staff Sgt. James Allen, said to Kappel: “Well, our luck is still holding out.” Kappel nodded.

With German defenses crumbling in the face of American determination, Captain Kappel and H Company converged on the rail bridge. Corporal John M. Fowler led the assault up a narrow flight of winding stairs, suffering wounds at the hands of German troops. But Fowler and his men refused to retreat—they killed and wounded several Germans, which impressed 12 to 14 others to surrender, the first POWs H Company had taken all day.

Captain Burriss led his I Company men toward the rail bridge. Pfc. Walter E. Hughes and his buddies were ordered to cut any wires they saw, as they were likely attached to explosives, most importantly those directly under the bridge’s center point. If they went off, the bridge, the advancing British tanks, and the whole plan would sink into the River Waal.

But more American troops were arriving, braving mortar fire. Captain Fred Thomas led Company G of the 3rd/504th across a raised road under artillery fire. The Americans had to advance in a single line due to shell holes.

Now the 1st/504th came across the Waal. There were about 11 boats left, some full of bullet holes. The paratroopers stuffed handkerchiefs, wool caps, gloves, and uniform pieces into the holes, which kept them afloat. One boat crew used its entrenching tools as paddles. Sergeant Ross Carter joined his fellow troopers in singing “Song of the Volga Boatmen” as they paddled across.

More German fire rained down on the fragile boats, blasting them to pieces in the river. Only a few were left as Company C stormed a beach full of bloodied and dying paratroopers. Lieutenant Milton Baraff led some troopers in a wedge formation to cover the extreme left flank.

A and B Companies moved to reinforce the assault on the bridges and Fort Hof van Holland. Battalion Headquarters Private Nicholas Mansolillo found Tech. 4th Class John T. Mullen lying in a pool of blood. “You could see the steam rising from the warm blood,” Mansolillo said later. They had been together since basic training at Fort Bragg.

Company A, in better shape than the previous assault force, move in on Fort Hof van Holland, with Captain Charles Duncan personally leading the 1st Platoon over the dike road, across the causeway, up the fort’s grass slopes, and into the German gun positions. Private Peter Schneider called upon the Germans to surrender, and 18 men came out, hands held high. But other Germans outside the fort tried to reoccupy the position. Private Robert Washko set up his Browning Automatic Rifle to repel this assault but was killed. Even so, Duncan alertly sent his 2nd Platoon to hold the ground, and the fort was secure. Down to a few boats, the last troopers to go over were from Company B.

On the south side of the Waal, the 505th and the Grenadier Guards continued their inexorable pressure through the city. The Germans began abandoning their positions and fleeing across the rail bridge. Lieutenant Allen McClain, commanding 3rd Battalion’s mortar company, watched the retreating Germans, saw more than 500 running across, and let them have it with his mortars, machine guns, and BARs, exacting a dreadful toll.

At 5 pm on the south bank, Major Tyler saw “someone waving (from the north end of the rail bridge). I had been concentrating so long on that railroad bridge that, for me, it was the only one in existence. I got on the wireless and radioed Battalion, ‘They’re on the bridge! They’ve got the bridge!’” The only problem was that Colonel Goulburn, commanding the Grenadier Guards whose tanks were to roll across, didn’t know which bridge Tyler’s excited message referred to.

The assault had overcome 34 machine guns, two 20mm guns, and an 88mm dual-purpose gun on the railroad bridge, all of which had devastated the boat crossing.

Now, Cook and his men had one more objective: the road bridge, which was much better equipped to handle the Grenadiers’ tanks. That job was up to Goulburn’s armor and Vandervoort’s paratroopers, and the D-Day hero was leading, as usual, from the front and by example. The immediate barrier to the 2nd/505th’s advance was a German 88mm gun near the bridge, which had been blasting open British tanks with regularity on the 19th, setting them ablaze. Lieutenant James E. Coyle, who led 3rd Platoon of Company E, was dug in close to the gun’s position. Coyle led five men through backyards of buildings and around to the end of the block, surprising the German gun crew from behind with fire from their rifles, killing one. The remainder fled to a nearby trench, and Coyle’s men treated them to more fire. The Germans abandoned the gun and retreated into a nearby park.

Company F had a more difficult time, facing well-trained and motivated men from 10th SS Panzer Division. Captain Robert Rosen, who had no combat experience prior to Holland, led his men in a premature assault, under heavy German fire, shouting “Follow me!”

By now, Vandervoort believed his battalion had suffered enough indignities, and as the clock read 4 pm, he and Adair ordered a decisive coordinated attack on the bridge, starting by taking Hunner Park once and for all.

Company F men took over houses that overlooked the park while Goulburn’s tanks drove toward it. The Americans sputtered suppressive fire on the German defenders as British armor and E Company regrouped and attacked again. Wurst’s assistant squad leader recalled, “Everybody went in with the idea that we were not going to pull back. If they take us back, they’re going to have to carry us back.”

The Germans held their fire until the Anglo-Americans were all exposed in the street and then opened up. Paratroopers fired from the hip as they ran forward, doing so at point-blank range: 25 to 150 yards. German snipers added to the destruction. Lieutenant Bill Savell, commanding E Company’s 2nd Platoon, was shot through both arms. Vandervoort watched F Company’s Lieutenant John Dodd get hit by a 20mm shell. As the lieutenant lay dying, his men charged the gun and obliterated its crew.

Vandervoort’s men performed their duties with incredible courage and pain. As his men and Goulburn’s tanks advanced, the Germans began retreating across the highway bridge, knowing that it was packed with explosives. To cover the withdrawal, their artillery and mortars on the north bank of the Waal loosed off at the Allied advance, particularly Goulburn’s tanks.

“With those Shermans bearing down on them, the Germans aimed most of their fire at those tanks,” Vandervoort said later. “Otherwise, most of the troopers would have been wiped out. Bullets bounced off Shermans like hailstones. Some were chipped, but none were holed. The Germans, stiffened by elements of the 9th SS Recon Battalion, kept firing full bore until overrun. Moving with the troopers, the tanks rolled over trenches and fired point-blank into air raid shelters. It was ‘walking fire’ with tanks—the effect was devastating. The air in Hunner Park turned blue with hand grenade, cannon, rifle, and gun smoke generated by hundreds of combatants.”

SS Captain Karl-Heinz Euling and 60 men under his command were the only ones to make it across the bridge. Of the 600 other defenders, mostly SS grenadiers and paratroopers, both highly skilled in last-ditch stands, 60 were taken prisoner. The rest fell to Vandervoort’s paratroopers and Goulburn’s tanks.

Meanwhile, at the north end Cook’s 504th men attacked German defenders, finding old men and Hitler Youth holding foxholes and trenches. Corporal Jack Bommer of the 504th’s Headquarters Company “killed boys not over 15 and men over 65 in their foxholes in the crossing. It was such an operation, everything went so fast and hectic—it’s hard to explain. Surrenders—I saw few of them … I did see old German men grab our M-1s and beg for mercy—they were shot point-blank,” he recalled.

The German defenders were no longer in much of a mood to fight. From their prepared positions on the river’s edge, they were willing to give battle, but once face-to-face with the ferocious American paratroopers, their MG42s and mortars silenced, the surviving Germans were eager to surrender.

German machine-gun fire from near the rail bridge pinned down Captain Burriss’s advancing men, but Private Ralph N. Tison, Jr., replied with his own machine gun. The American onslaught forced the Germans to abandon an anti-tank gun positioned between the two bridges. A Gammon grenade disposed of another anti-tank gun and its five-man crew. Sergeant Leoleis and four other I Company men stormed a house, killing eight Germans.

It was nearly 6 pm, and Burriss and his men were finally running up the north approach to the highway bridge. Burriss could hear gunfire at the southern end, but nothing at the north end. He sent some men to cut any wires, rightly believing they connected the explosives beneath the structure to its detonators. The first Americans to reach the north end of the bridge were Pfc. John W. Hall, Jr. and Pfc. Robert A. Hedberg, along with Private Norman J. Ryder.

Burriss led another group up the stairs to the bridge’s sidewalk and saw a lone German, who surrendered. Burris thumbed him back and summoned more men to start across the bridge and cut wires. As they did, a German strapped high in the girders shot an enlisted man next to Burriss. The paratroopers killed the German. Two days later, the German’s body was still hanging from the bridge structure.

With the north end secured, Captain Kappel organized a roadblock to defend it, amid German bodies that littered the highway. But even though the 3rd/504th had achieved its objective at high human cost, they had done so at another high cost—ammunition. Some paratroopers were down to their last clip. They needed relief, quickly.

It was coming. As the 3rd/504th claimed the bridge’s north end, the 2nd/505th and the Grenadier Guards approached the bridge’s south end. Major John Trotter and his exec, Captain Lord Peter Carrington—Britain’s future Foreign Secretary—ordered Sergeant Peter Robinson to take his troop of four tanks into the assault, immediately. “You’ve got to get across at all costs,” Trotter said. “Don’t stop for anything.”

Then Trotter shook Robinson’s hand and said, “Don’t worry; I know where you live and I’ll let your wife know if anything happens to you.”

“Well, you’re bloody cheerful, aren’t you, sir?” the Dunkirk veteran replied. He hopped into his tank, and the Shermans clattered in single file around the anti-tank barriers onto the structure. Robinson’s gunner, Guardsman Leslie Johnson, opened up on the SS Grenadiers tied to the girders. “They were falling out like ninepins,” he said later. German fire was heavy, but Robinson’s tank seemed to live a charmed life. “I swear to this day that Jesus Christ rode on the front of our tank,” Johnson said later.

Everybody from Browning to Robinson expected the bridge to be blown sky-high. A German 88mm gun opened fire on Robinson’s tanks, its crew recognizing that one wrecked tank would in turn wreck the assault.

“The lead Sherman fired its cannon as fast as it could load and sprayed the road ahead with .30-caliber machine-gun. The 88 fired half a dozen—more or less—near-misses, ripping and screaming with an unforgettable sound—past the turret of the tank. In the gathering dusk they looked like great Roman candle balls of fire. Brightly glowing, 17-pounder cannon shots rocketed back along with flashing machine-gun tracers. Suddenly, the 88 went silent. One of the tanks’ .30-caliber armor-piercing rounds had penetrated the soft metallic cap of the 88’s recoil mechanism, causing the gun to jam. That improbably, long-odds happenstance of good marksmanship and good luck ended the shoot-out at the bridge,” Vandervoort recalled.

From his command post northeast of the bridge in Lent, 10th SS Panzer Division CO Maj. Gen. Heinz Harmel watched the tanks and studied the explosives placed in the bridge’s middle. He had been ordered not to blow the bridge, but he was not going to let it fall into Allied hands. As Robinson’s tank reached the center of the bridge, he shouted to his engineer: “Get ready … let it blow!”

The engineer hit the plunger. Nothing happened.

Harmel yelled, “Again!” Still no response. Harmel figured that all the heavy artillery fire had shredded the initiation cable.

Harmel turned to his staff and said, “My God, they’ll be here in two minutes. Tell Bittrich. They’re over the Waal.”

Robinson was forced to trade tanks with another one when his radio went out, but he kept advancing. Then he saw more troops in front of him, and his men opened fire, not recognizing their uniforms. But Robinson did. “Cease fire, those are our feathered friends,” he told his men. Then he smiled and waved at the Yanks.

Burriss and his men were ready to run. They couldn’t tell if the approaching tanks were German or British. He ordered his troops to get off the structure and over the embankment and ready their Gammon grenades. Then they saw the distinctive silhouettes of approaching Sherman tanks. Burriss and his men leaped up to greet them.

The tanks were joined by an infantry company of the 3rd Irish Guards. That enabled Major Cook to expand his tenuous bridgehead despite German artillery fire. Wounded men could now go back to hospitals across the bridge—there were only five boats left.

Among the wounded was Major Abdallah K. Zakby, the 1st/504th’s executive officer, who had suffered a shell burst in his left leg and right hand. He found that the hospital’s “receiving room was full of wounded men, much more terrible than mine. I was carried to the operating table. A young doctor, whom I had not seen since 1941, and whom I knew well at Fort Dix, New Jersey, operated on me. As luck would have it, the bone was not shattered—just seared—but all my flesh and ligaments in the middle of my left leg were burned. He put 17 drains around the leg,” Zakby said later.

Why the explosives intended to blow the bridge didn’t go off was a cause of contention. After the war, the Dutch honored an 18-year-old resistance fighter named Jan van Hoof for disabling them, on slim evidence. Gavin and Jones disagreed. SS General Hans Albin Rauter, who headed the Gestapo in The Netherlands, claimed that SS engineers had removed the charges from the bridge. Jones found that hard to believe. The likeliest cause was that British shellfire ripped up crucial wires and detonating mechanisms, which was why Jones was able to capture 80 pioneers—they were trying to repair the wires during the battle.

The bridge was in Allied hands, but German artillery rained down on both sides of it, and other German troops were still fighting in Nijmegen. In the gathering dark, short of fuel and ammunition, Adair was reluctant to make a night advance up the road to Arnhem, particularly up an elevated highway that would make his tanks exposed to German guns. He could bring up his infantry in support at daylight.

Adair’s decision, backed by Horrocks, infuriated Tucker and Burriss, who felt deep brotherhood with the suffering British paratroopers at Arnhem. They didn’t know it, but while Cook’s men were seizing the Nijmegen bridge, Bittrich’s tanks had finally cleared the last British defenders from the Arnhem bridge. Gavin was aware of his men’s feelings, but he knew the difficulties that 30 Corps faced, particularly their supply difficulties.

An outraged Burriss yelled at Carrington over the Grenadiers’ failure to advance. But that failure was not Carrington’s fault—it was the fault of Adair, Horrocks, and ultimately Montgomery for failing to impose urgency on the advance.

Instead of attacking as dusk gathered over the north end of the Nijmegen bridge, the British troops “consolidated” and the Americans “dug in” against a German night assault. The British annoyed their American cousins of the 504th further by breaking out pots to heat up bully beef and brew tea. The sight upset the Americans, making the British appear not to care about their buddies at Arnhem. Actually, British troops regarded their tea and compo ration breaks as simply what they did between getting new orders. Neither the paratroopers nor the Guardsmen could know what was going on above them.

And Cook’s men had not seen how the Grenadiers had also just fought with the 505th, an extremely harsh battle to reach and cross the bridge in the first place, an action that was a masterpiece of two different units from two different countries combining arms and proficiency to defeat a powerful entrenched enemy. Had it gained more attention from postwar historians, the Grenadier Guards and 2nd/505th’s action would be seen for what it was—a model of Allied cooperation at its absolute best. But nobody would notice, except those who had fought there.

What would be remembered, and deservedly so, was the courage and valor of the 504th in its boat crossing of the Waal. American paratroopers who had never made an assault river crossing had done so on one day’s notice and triumphed over a powerful enemy. The assault would go down deservedly into American military lore. The 3rd/504th could only console themselves with the ironic name they gave their river assault: the “Waal Regatta.” Corporal Jack Bommer called it “the most vivid show of courage, patriotism, and love for one’s way of life I have ever seen.”

Next morning, when the Guards resumed the offensive, the Germans had moved in a battle group of tanks, and they stopped the British cold along the elevated highway. The British would have to evacuate the 2,163 survivors of the 10,000-man 1st Airborne Division, abandon the offensive, and consolidate the ground, having taken a 60-mile salient.

That was no comfort in the American casualties: Company C of the 307th Airborne Engineers lost eight killed and 26 wounded; 3rd/504th lost 28 killed, one missing in action, and 78 wounded; 2nd/505th suffered as well. Company F lost 17 killed and 23 wounded in the two-day attack on the bridges. Company E lost nine killed and 25 wounded. German casualties were harder to figure: dead Nazis lay all over Hunner Park, and 267 were counted on the road bridge.

But for everyone who survived this St. Crispin’s Day on the Waal, there was a tribute offered by Browning himself, a Guards officer of World War I experience, given spontaneously to Horrocks as the 3rd/504th made its river crossing and assault: “I have never seen a more gallant action.”

Author David Lippman hails from New Jersey. He contributes frequently to WWII History on a variety of topics.