1939-1945. The world had never seen anything like it. Fifty million dead. Every continent except Antarctica inflamed in some way. Europe, the most powerful continent, overrun with fighting, whole cities, some a thousand years in the making, reduced to rubble. Asia, the most populous continent, suffering appalling slaughter.

Like most wars, this one did not end as it had begun. Leaders, planners, and thinkers foresaw one thing and got another. Germany felt that with a few swift jabs, the “living space” it believed it deserved would be won. Japan felt, too, that with a series of quick victories, it would become master of Asia.

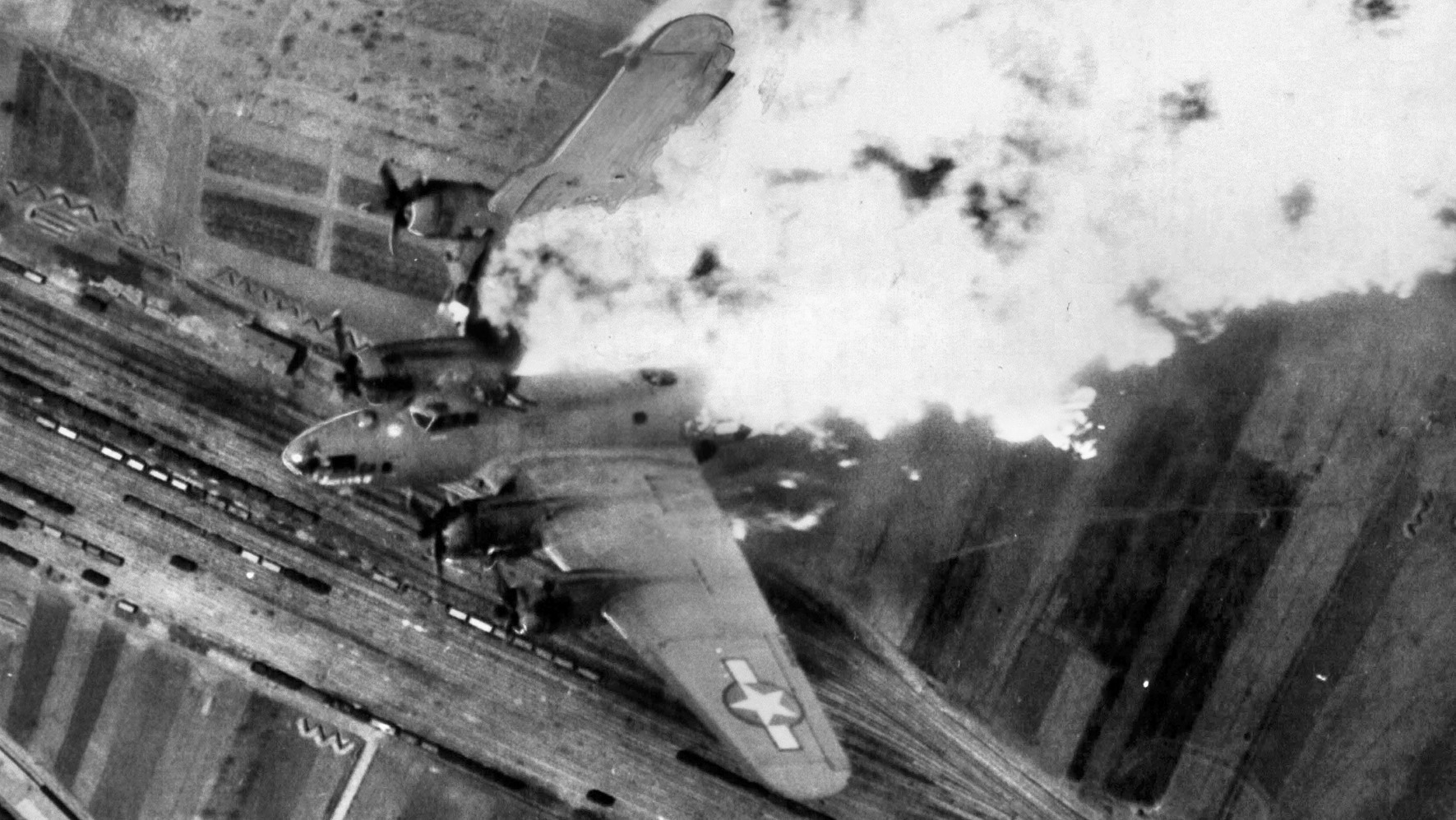

Somewhere along the way, it all changed. The “decadent” democracies and the “rotten” USSR reeled but did not fold. They organized to strike back. With a vengeance they did, sending waves of men and machines against fascists who thought that by virtue of being a “superior race” they were destined to rule the world. They sowed the wind, and they reaped the whirlwind.

In the terrible retribution visited upon the criminal aggressor nations, one way of life was extinguished and another began. The war was a great divide, its scar still evident across time: before, nation-states that could covet territory and seek to grab it; after, a world divided largely between capitalist and communist, each with atomic weapons that would end human life.

It was as if a giant evil was loosed upon the world, and six years were needed to compress that evil partway back into its box.

But the war did not come from nothing. It’s difficult to think of World War II without the agonies of the Depression. The unemployed and the desperate brought Hitler to power in 1933, believing he could return their country to prosperity. Japanese soldiers in Manchuria grew increasingly militant and covetous of Chinese territory that they believed might help feed their families back home, whom they perceived as unemployed and starving. So the fascists thought they would better their own lives at the expense of others. And the war came.

Looking back across half a century, especially from the vantage point of the United States, it is all too easy to recall the war as a thrust by fascist aggressors crushed in a counterthrust by the Allies. This is far too simple a portrait, and closer examination reveals swirls of complexities, not just among nations but within nations and the soul of humankind.

The British killed 1,300 French sailors in their bombardment of the French Fleet. The French Air Force bombed the British at Gibraltar. German generals tried repeatedly to assassinate Hitler. Hundreds of Saipan mothers slew their children and themselves rather than face life with Americans. The most decorated American combat regiment of the war was Japanese. Men tortured women to death. Supersonic rockets rained down on civilian cities. Germans, once thought to be the most civilized of Europeans, imprisoned millions of innocent civilians including children, then created factories for killing them. More than any other soldiers they faced in Italy, Germans feared not blue-eyed Aryans but Gurkhas. African Americans, who were second-class citizens in their own country, made outstanding fighter pilots. Priceless works of architecture and art a thousand and more years old were reduced to fragments and ash. Rich indeed is the story of these years.

There was also courage and heroics aplenty, and brilliance as well as stupidity, common virtues and uncommon ones. Men and women loved each other and were steadfast; parents loved children and cast their lives away for them. Every sort of human misery was faced and endured: murderous heat and killing cold, starvation, thirst, disease, imprisonment, homelessness, betrayal, confusion, flashes of utter horror.

Somehow we came out of it and patched ourselves together. And we in the West seemed somehow even more ready and vigorous than before to stand up for the rights and dignity of every man and woman.

All this was what is known as World War II. A struggle for the planet and for the soul of man. A rife struggle of the human condition.

We will bring it to you, because it should be remembered, because it is still relevant, because it still holds its deep and abiding lessons.

Brooke C. Stoddard

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments