While American troops slugged it out with the Japanese on the Philippine island of Leyte, one of the greatest battles in the history of naval warfare raged far and wide in the surrounding waters. The Battle of Leyte Gulf, fought October 23-26, 1944, was actually a series of smaller naval actions that eventually gutted the Imperial Japanese Navy as a fighting force.

One of these encounters, the Battle off Samar, includes one of the most gallant episodes in the combat history of the U.S. Navy, but has also led to an enduring controversy. On October 25, the escort carriers, destroyers, and destroyer escorts of Admiral Thomas Kinkaid’s U.S. 7th Fleet stood off the landing beaches at Leyte, supporting the efforts to supply and reinforce the troops ashore. The escort carriers’ aircraft and the small warships were there as a screen against Japanese planes and submarines that might threaten the landings. They were never intended to take on a powerful enemy surface fleet. Bu that is just what happened.

Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, commander of powerful Task Force 38, which included Essex-class fleet carriers and fast battleships, was ordered to cover the landings against any substantial enemy naval threat; however, the first priority as Halsey saw it was the destruction of the remaining Japanese aircraft carriers.

The Japanese realized this, and in keeping with their penchant for complex planning devised a scheme to lure Halsey away from the invasion beaches to attack the Northern Force, under Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa. The Japanese carriers had actually been depleted of planes and posed only a nominal challenge to any American shipping. However, the Japanese correctly assumed that their presence would be enough to attract Halsey’s full attention.

When the Northern Force was located, Halsey ordered the fast battleships and carriers of Task Force 38 to steam toward Cape Engano (ironically the name translates from Spanish as “lure” or “hoax”) to annihilate the enemy carriers. In doing so, he left the small ships of the 7th Fleet, particularly Task Force 77.4.3, also known as “Taffy 3,” under Admiral Clifton A.F. Sprague, without support.

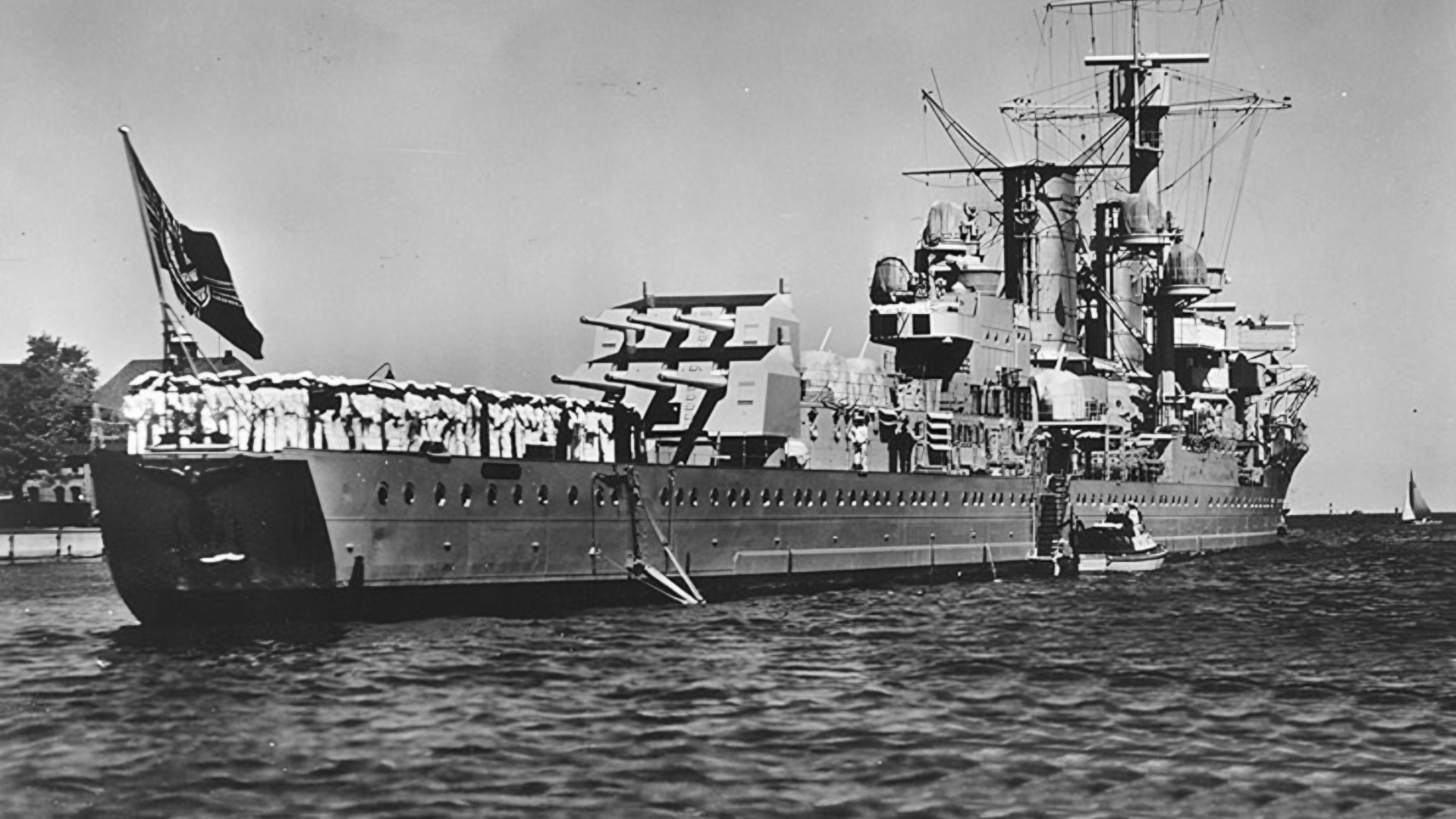

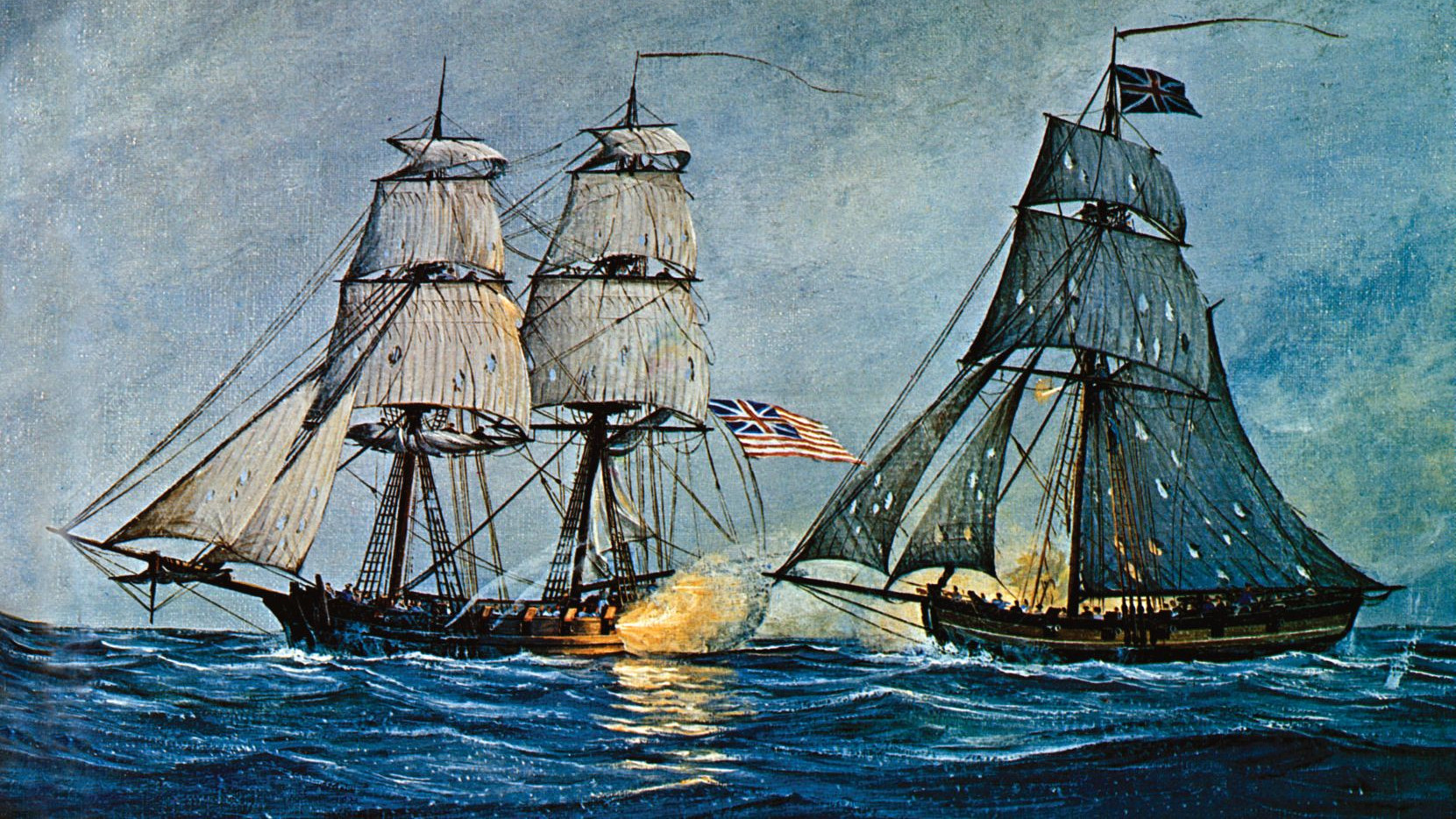

On the morning of October 25, a powerful Japanese force of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers, including the most powerful warship in the world, the super battleship Yamato mounting 18-inch main guns, steamed through San Bernardino Strait into the area guarded by Taffy 3 and other elements of the 7th Fleet. Admiral Takeo Kurita ordered his ships to attack. In response, the gallant American destroyers and destroyer escorts gamely fought back, chasing salvoes from heavy Japanese guns, firing away with five-inch main batteries, and charging in to launch torpedoes while forcing the enemy ships to take evasive action. The escort carriers’ available aircraft made repeated attacks, some without bombs and even dropping depth charges. They strafed and harassed the Japanese.

In the end, the heroes of Taffy 3 lost two escort carriers, two destroyers, a destroyer escort, and numerous aircraft, and sustained more than 1,000 casualties. In exchange, though, the Japanese lost three cruisers sunk and three damaged. Kurita was confused. As his task force neared the brink of success, approaching the vulnerable transports and supply ships off the Leyte landing beaches, Kurita lost his nerve and ordered his force to retire. He actually believed he had encountered the heavy ships of Halsey’s Task Force 38, which was far to the north. The heroism and sacrifice of the American sailors and airmen, against overwhelming odds, had saved the day—miraculously.

Halsey concluded his northern adventure with little result. His conduct became the subject of vigorous debate, and there was plenty of finger pointing. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander-in-chief of the Pacific Fleet, wrote to Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations, plainly stating, “It never occurred to me that Halsey, knowing the composition of the ships in the Sibuyan Sea, would leave San Bernardino Strait unguarded, even though the Jap detachments in the Sibuyan Sea had been reported seriously damaged.”

Halsey defended his conduct for the rest of his life.

—Michael E. Haskew