By Eric Niderost

It was the afternoon of September 20, 1863, and the right wing of the Union Army of the Cumberland was in full flight at the battle of Chickamauga in northern Georgia. This was not an orderly retreat, but a full-fledged rout, with soldiers who had fought bravely all day suddenly turned into panic-stricken fugitives. A reporter for the Cincinnati Daily Gazette caught the horrors of the flight when he wrote that “men, animals, vehicles, became a mass of struggling, cursing, shouting, frightened life.”

The fleeing blue-clad troops were goaded by the sounds of the advancing Confederates, who seemed to be on all sides, an inexorable gray wave about to engulf them at any moment. Their fearsome Rebel Yell heard distinctly above the din of battle and the sounds of headlong retreat, was an audible whip that spurred even greater panic.

When the escape road narrowed, the situation turned chaotic. Men, horses, mules, ambulance wagons, artillery carriages and cannons and caissons became jumbled together bringing the retreat to a grinding halt. Yet on other parts of the battlefield the fighting continued unabated with the characteristic storm of canister and musketry.

Union Major General William S. Rosecrans, the commander of the Army of the Cumberland, was being swept along with the rest. Rosecrans had lost his ability to direct events. Rosecrans clung to one hope, which was that Maj. Gen. George Thomas’ XIV Corps was still in the fight. “Old Rosy” wanted to join Thomas, but it was hard to swim against the tide of fugitives, and the way seemed blocked at every turn.

Rosecrans allowed himself to be persuaded to continue on to the main Union base at Chattanooga and organize the defenses in that location. The city was a key strategic location in southeastern Tennesee, and therefore was bound to be the next Confederate target. But Thomas, who was still fighting his own hard battle on the Union left, was unaware of the Union disaster and had to be informed. Rosecrans’s aide, Brig. Gen. James A Garfield, who would one day be president of the United States, was dispatched to inform Thomas of the bad news.

Dejected as well as defeated, Rosecrans reached his Chattanooga headquarters at 4 p.m. He was unable to dismount or even walk without assistance. Helped by his aides, Rosecrans somehow managed to reach a chair, where he slumped down head cradled in his hands. Dazed and overwhelmed by the sheer magnitude of his defeat, he never seemed to have fully recovered. Rosecrans had acted “confused and stunned like a duck hit in the head,” U.S. President Abraham Lincoln said afterwards.

Rosecrans’s opponent was General Braxton Bragg, commander of the Confederate Army of Tennessee. Although a West Pointer like Rosecrans, Bragg was a mediocre general at best, and a man who was thoroughly despised by both his subordinates and the Southern people. His close friendship with Confederate President Jefferson Davis was the only reason that he remained in a position of authority.

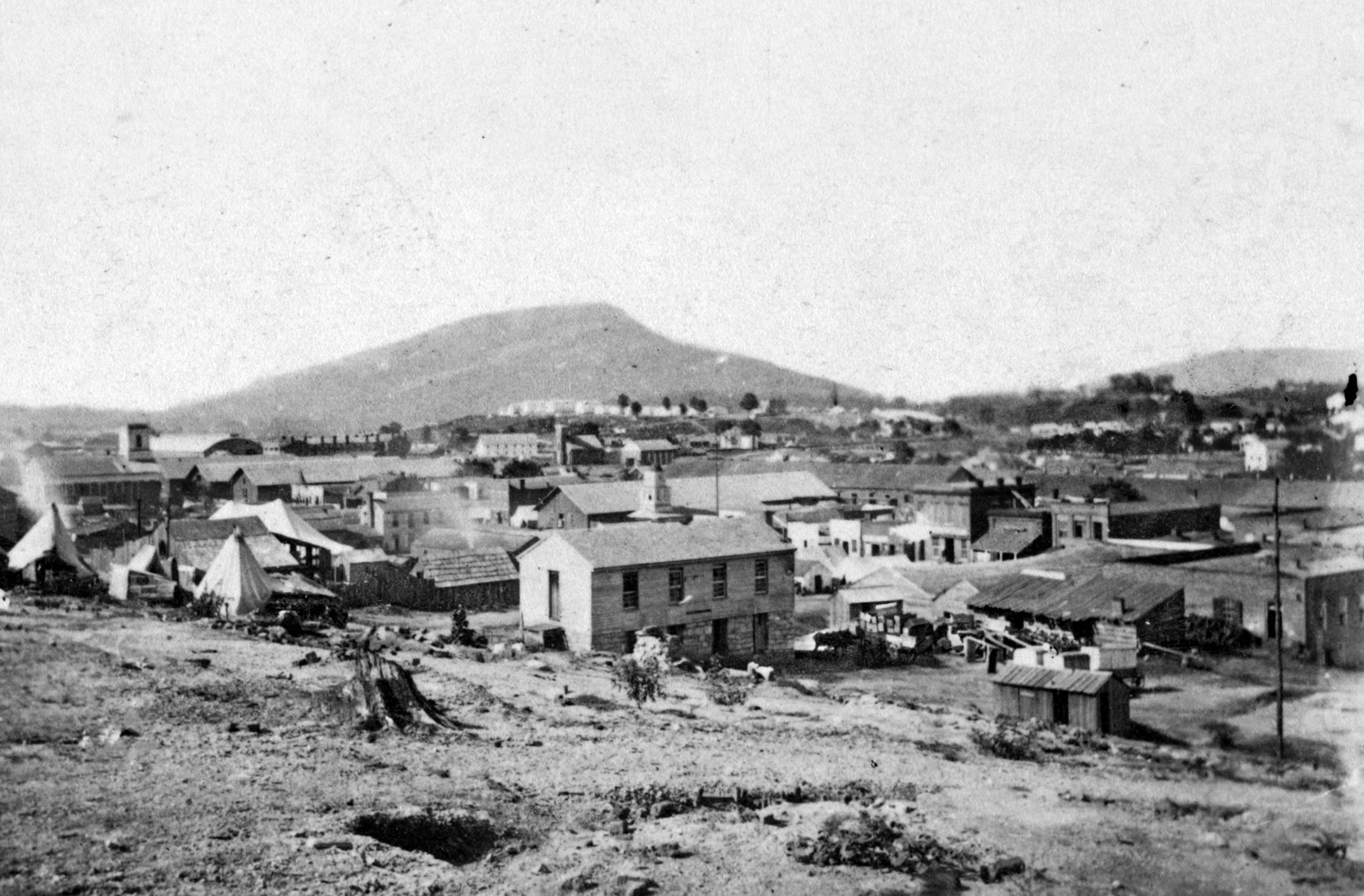

Both Rosecrans and Bragg knew that Chattanooga was going to be the strategic locus of the whole campaign. Chattanooga was a town of just 3,500 souls, nestled by the sinuous Tennessee River in the heart of the Cumberland Mountains, which were part of the southern end of the Appalachians. Although small in population, it loomed large in a strategic sense, because vital railroads that linked the eastern and western parts of the Confederacy converged in its vicinity.

The Confederacy had funneled arms, munitions, textiles, and foodstuffs from Georgia’s robust war industries through Chattanooga to the rest of the South.

Bragg found the Union army fully entrenched at Chattanooga. Since there was almost no likelihood of being able to lure them out, he faced a formidable dilemma. One option would be to try and outflank Rosecrans by crossing the Tennessee River either above or below the city, but that was not really viable given that Bragg’s army lacked materials to build a pontoon bridge across the river. Moreover, the Army of Tennesee lacked wagons needed for supply. Another option was a direct assault, but Bragg knew that Chattanooga’s fortifications were just too strong to even consider it.

Yet another option was to try to starve the Union army out of the city, and Bragg embraced this option. He had received intelligence that the Yankees had only six days of rations. This was a win-win situation from Bragg’s point of view, because a siege would give him time to accumulate enough materials to cross the Tennessee River.

Chattanooga may have had formidable defenses, but it was also situated in a valley that was surrounded by high ridges and mountains. The city was at the bottom of a geologic bowl where the city and its environs could be clearly seen from above.

Ironically, the Federals originally had stationed troops on Lookout Mountain, but they were withdrawn when Rosecrans decided the position was untenable. Bragg put three Confederate brigades on Lookout Mountain, a rocky spine that rose 1,100 feet into the sky, but in places topped 2,100 feet.

Missionary Ridge, just to the east across Chattanooga Creek, was 400 feet high. Bragg ordered the ridge to be fortified against any Union attempt to take it. There were trenches at its base and crest, as well as an unfinished line of rifle pits halfway up the slope.

It was clear from the very start that the Army of the Cumberland was going to have a supply problem. The Confederates had all, or nearly all, of the approaches to the city well covered. Missionary Ridge guarded the eastern approaches, and formidable artillery on Lookout Mountain commanded all the approaches from the south and west. The only way left was from the north, via a wretched mountain road almost impassable in wet weather and vulnerable to Confederate cavalry raids.

While the bottled up Army of the Cumberland grappled with a growing supply crisis, other changes were in the works. Lincoln created a new Division of the Mississippi, which included the territory from the Mississippi River to the Appalachians, and placed Major General Ulysses S. Grant, the conqueror of Vicksburg, in overall command. One of the first things Grant did was to replace Rosecrans with Thomas, whose performance at Chickamauga had gained him the sobriquet “The Rock of Chickamauga.”

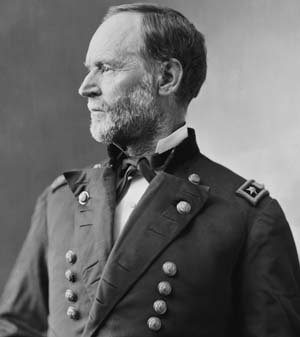

The War Department ordered reinforcements to Chattanooga. Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman was headed east with four divisions totaling 17,000 men. But their march would be a slow one given that Sherman had orders to repair the Memphis and Charleston Railroad as he moved east along its path. Other Union forces were on their way as well.

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton persuaded Lincoln to detach two corps from the Army of the Potomac and send them to Chattanooga. One was Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s XI Corps, and the other was Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum’s XII Corps. That would bolster the city’s garrison by another 20,000 men. Lincoln recalled Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker to command the two-corps expeditionary force.

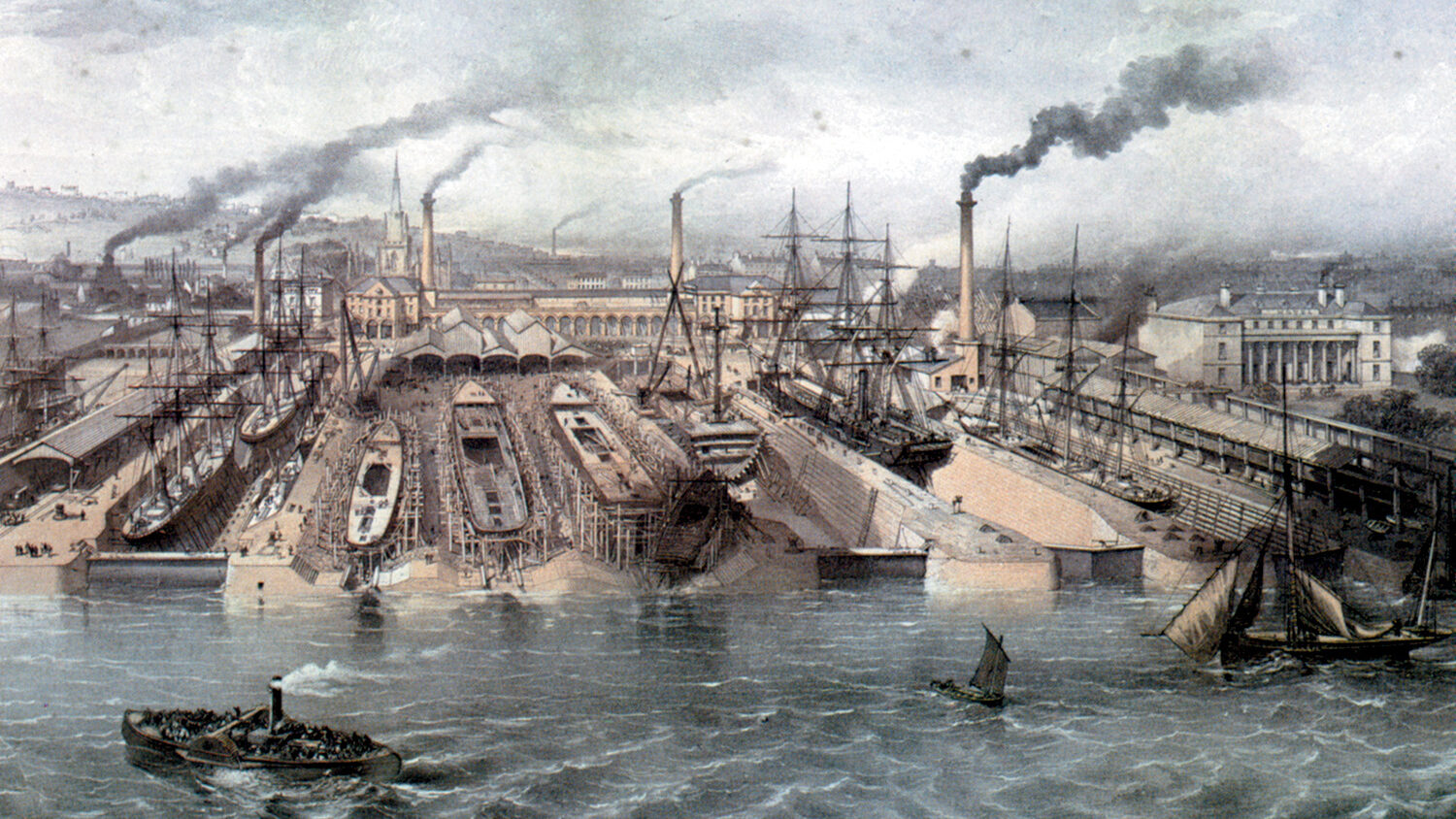

Stanton, although often brisk and authoritarian, was at his best here. He summoned several railroad presidents to his office and told them what they had to do. Orders were issued, trains assembled, and 40 hours after the decision, the first troops were on their way to Chattanooga. It was an epic 1,233-mile trip, and 11 days later 20,000 men, horses and equipment arrived at their destination. It was a feat of logistics even greater than the earlier Confederate effort, and set a record for the swiftest and longest movement of a large body of troops before the twentieth century.

Grant’s arrival was like a tonic to the hard-pressed men of the Army of the Cumberland. His was a curious charisma, for outwardly he was quiet, unprepossessing and sometimes even a bit shabby in appearance, and yet somehow he exuded confidence, and that confidence spread through any army he commanded.

Nicknamed “Unconditional Surrender” for his victory at Fort Donelson the year before, Grant had to travel to Chattanooga via the same miserable and dangerous road that supplied the Army of the Cumberland with its scanty provisions, so he could see firsthand the problems that confronted him. The route was steep, narrow and slippery and often a muddy quagmire as a result of constant rains. The road “was strewn with the debris of broken wagons and the carcasses of thousands of starved horses and mules,” wrote Grant.

Grant arrived in Chattanooga on October 23, 1863. He had severely injured his leg a few weeks earlier, but to his surprise and relief his limb felt good in spite of the arduous journey. Grant was pleased to find a plan already developed to ease the food and supply situation. All he needed to do was to approve it.

Grant quickly authorized an attack on Confederate-held Brown’s Ferry on October 27 to establish a supply corridor into the beleaguered city. Once the ferry was in Union hands, supply steamers began delivering food and fodder to the troops defending the city by way of the secure supply corridor designed by Maj. Gen. William “Baldy” Smith known as the “Cracker Line.”

On the Confederate side, Bragg’s growing unpopularity finally came to a head. Longstreet and several other subordinate officers sent a petition to Davis that declared that Bragg’s health “unfits him for any command in the field.” Bragg’s health was a factor for he was often sick, but this was largely an attempt to give Davis a face-saving reason to dismiss the general.

Davis refused to take the bait, but did take the time and trouble to make the long journey from Richmond, Virginia, to Bragg’s headquarters to resolve the dispute. Grievances were aired, but Davis refused to budge. He allowed Bragg to remain in command. But Davis, who considered himself a military man and chafed at his civilian role, gave Bragg some bad advice. The Confederate president instructed Bragg to send a sizeable force to drive the Federals out of Nashville.

Bragg complied with the order on November 4. He dispatched Longstreet with 15,000 men to capture Nashville. He later reinforced him with an additional 5,000 troops. Longstreet felt this was a fool’s errand, because it reduced Bragg’s command to 45,000. He also believed the 20,000 he had under his command was insufficient to capture Nashville.

In the meantime, Grant’s army was still bottled up in Chattanooga. There were periods, of relative calm, and sometimes there was some fraternization between outlying pickets. Coffee, tobacco, and other items were occasionally exchanged, and the friendly enemies might even chat and swap a few lies.

It was said that Grant once appeared at a creek that supplied water for both sides. “Turn out the guard, commanding general!” some Union soldiers shouted. Grant, not wanting to attract attention, dismissed the men. The same cry was heard again, only this time it came from the Confederate side of the creek. Grant looked in amazement as a line of Confederate soldiers was presenting arms. Amused at the sight, the Union commander returned the salute.

But such light-hearted moments had to give way to the business of war. The 17,000 soldiers of Sherman’s Army of the Tennessee arrived at Chattanooga on November 15. It appeared the initiative would be in Grant’s hands. For the first time parts of three main Federal armies—the Army of the Cumberland, the Army of the Tennessee, and the expeditionary force from the Army of the Potomac—were united, a combined force of 60,000 men. But the Confederates still held the high ground surrounding the city, and Grant was not about to order suicidal frontal attacks if he could help it.

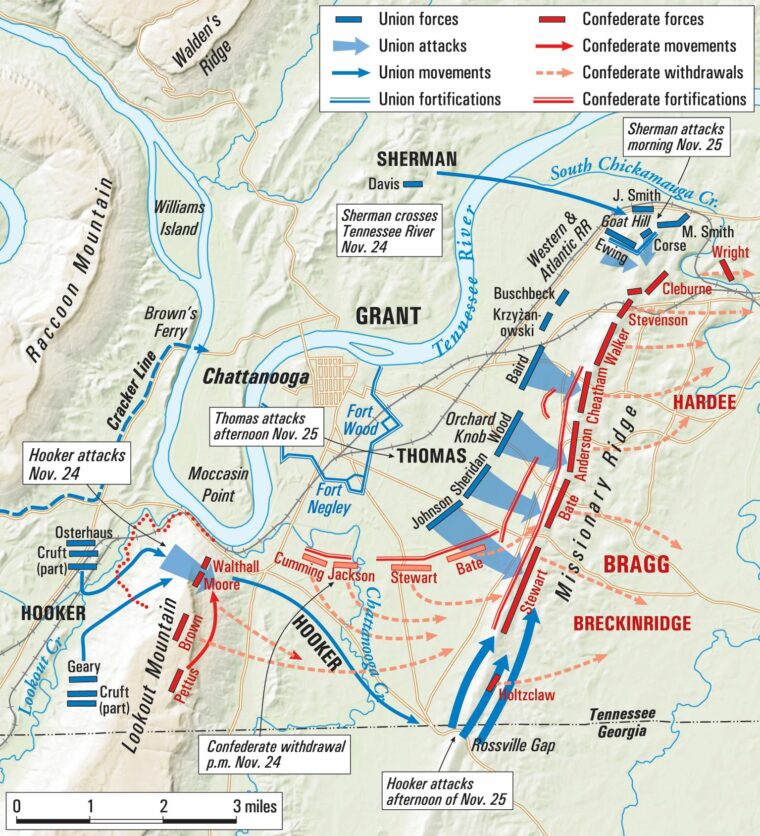

Grant decided that flank attacks against Missionary Ridge would produce the desired results. Sherman and his battle-hardened veterans of the Army of the Tennessee would play a major role in the drama. Their chief target would be the Confederate right, anchored on the northern edge of Missionary Ridge, and a place where Bragg’s supply line joined his line of communication with Longstreet in the north.

Sherman would march northward, maneuvering in such a way as to keep Bragg guessing at his real destination. Once in position, and safe from Confederate prying eyes, the Army of Tennessee would launch an attack that would surprise the gray troops and roll up their northern, or right, flank. At the same time, or at least close to the same time, General Hooker would take Lookout Mountain on the Confederate left flank.

But once again, the weather wrought havoc on Grant’s well-laid plans. Sherman’s men were old hands at foot slogging marches, but the rains turned roads into quagmires. It would take Sherman three days to get into position, and in that time Grant was faced with a new concern.

There were reports, which proved false, that Bragg was withdrawing. Grant had to find out for sure, so while Sherman and his long-suffering Army of the Tennessee marched over wet ground to their flank attack position, Thomas was ordered to scout things out with a reconnaissance in force. In the Chattanooga Valley, between the town and Missionary Ridge to the east, there was a tree-studded hillock named Orchard Knob. That was Thomas’s main objective.

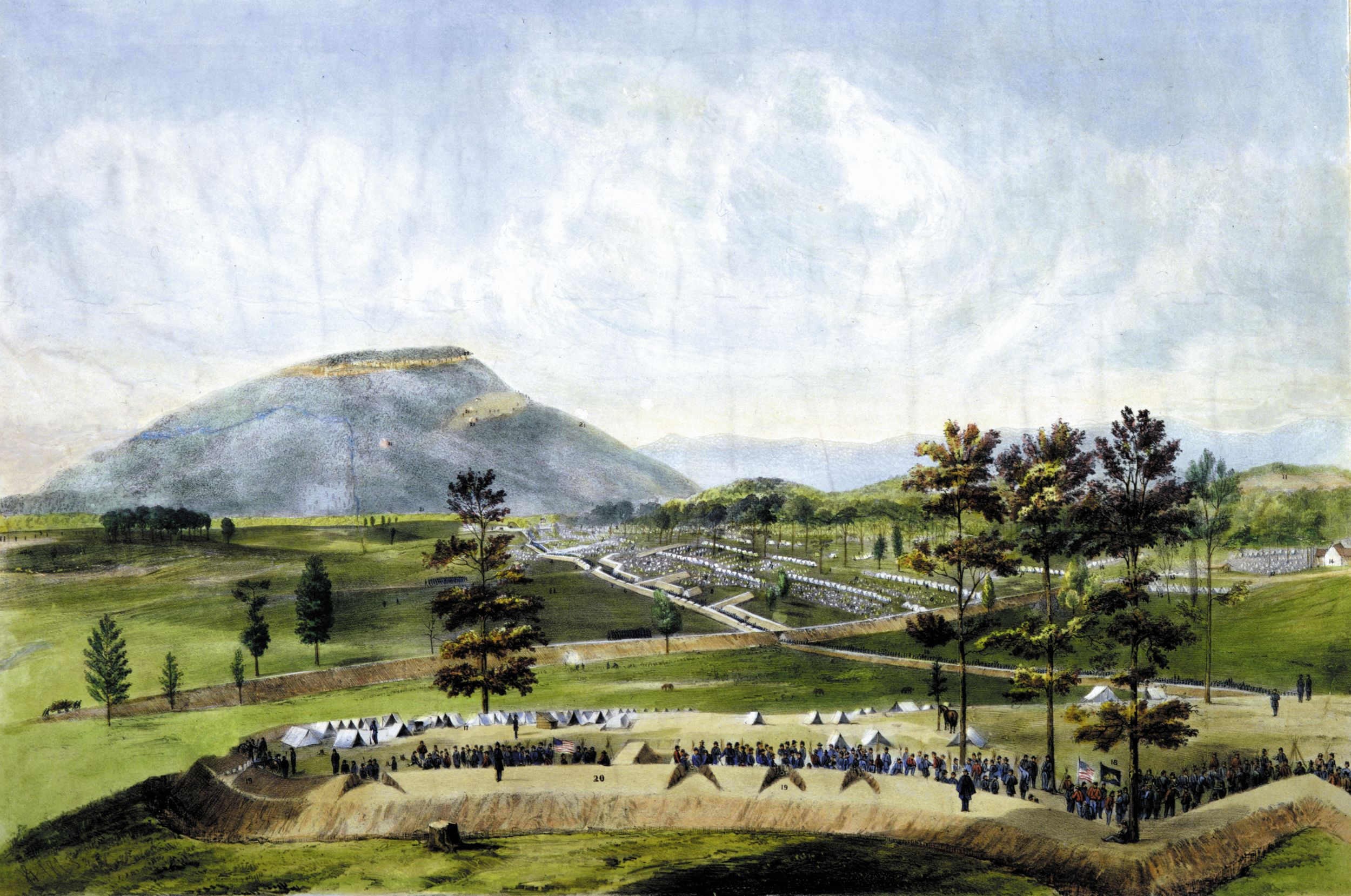

Because of the valley’s geography, Thomas’s march on November 23 was a spectacle for both sides. The surrounding hills formed a natural coliseum where blue and gray spectators not directly involved could witness the unfolding drama. Bayonets gleamed and sparked in the sun, and national and regimental flags stirred in the breeze.

Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana, on scene and standing next to Grant, could hardly believe his eyes. “The spectacle was one of singular magnificence,” he wrote. A cannon boomed, and at that signal Thomas’ whole command, 14,000 strong, moved forward. Bragg had just 600 Confederates at Orchard Hill, and after a token resistance they understandably decided to quickly withdraw.

The action at Orchard Hill was only a curtain raiser, but nevertheless a welcome one. It meant that the Union lines were that much closer to the Confederate center. The Orchard Hill battle, more like a heavy skirmish, also influenced the Confederate side. Bragg took notice when he saw that Grant was on the move, and tried to take steps to checkmate the Union commander.

Bragg stopped Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne and his men from boarding a train that would have taken them to Knoxville. Cleburne was an Irish immigrant who had served a stint in the British army. Cleburne’s ability to hold ground where others failed earned him the nickname “Stonewall of the West.”

On the morning of November 24 Hooker’s troops started out on their assignment to take Lookout Mountain, the anchor point of the Confederate left flank. It was hoped that these movements would act in concert with Sherman’s push on the north, or right flank, of the Confederate line. Caught between two fires, Bragg’s army would be squeezed and ultimately crushed. Hooker had suffered a humiliating defeat at Chancellorsville in May 1863, and so this would give him a chance to redeem himself.

The Confederate defenders at Lookout Mountain were at first amused by the site of Yankee infantry struggling up the hill; that is, when they could catch a glimpse of the blue skeins of men through intermittent patches of dense fog. The Confederates had 7,000 men posted on the hill under the command of Brig. Gen. Carter Stevenson, but he had arrived the night before and was unfamiliar with the ground. That was bad enough, but his troops were too widely scattered to furnish an effective defense.

By contrast Hooker’s troopers were concentrated, and so 10,000 bluecoats were advancing against 1,489 Confederates in their immediate area. Worse still, from the Confederate point of view, was the fact that their artillerymen could not depress their guns low enough to shoot at the attacking enemy. That was not a problem for Union artillery, which quickly found the range and subjected the gray troops to a punishing and bloody barrage.

Nevertheless, the Confederates gave ground reluctantly, and the fighting grew ever more intense with each passing hour. It was clear that the gray clad troops had no monopoly on courage. Confederate Brig. Gen. Edward Walthall was impressed by the Union soldiers. “I have never seen them fight with such daring and desperation,” wrote the former lawyer from Mississippi. Nightfall brought an end to the fighting on Lookout Mountain, but the issue was still undecided. The whole mountain twinkled with campfires from both sides, reminding some of flowing lava, and occasional muzzle flashes from firing muskets further added pinpricks of light to the inky void. The night was cold and clear, and both sides were awed by an almost total lunar eclipse. It seemed a bad omen, but it was unclear for which side it spelled disaster.

The next morning the Union forces on the slopes discovered that the Confederates had withdrawn during the night. Bragg had ordered it, in part because he feared a heavy attack by Sherman on the Missionary Ridge right flank, and felt the Lookout Mountain troops would be better used at that location. At first light, Captain John Wilson and five men of the 8th Kentucky climbed to the Lookout Mountain summit. Kentucky was a slave state, but with divided loyalties, and the 8th Kentucky was a Unionist regiment.

The Kentuckians unfurled their flag just as the sun’s rays hit the peak and bathed its slopes with a bright morning glow. The Stars and Stripes could be seen clearly from the valley below, and joyous cheers erupted from thousands of throats at the spectacular view. Lookout Mountain had been a thorn in the Union army’s side for weeks. There was visible proof that the siege and its attendant sufferings for those Union forces involved were officially at an end.

Lookout Mountain immediately became a place of romance, of epic battle victory, when in reality it was a hard-fought skirmish. Grant insisted it was “one of the romances of the war,” but the legend persisted. Because of the earlier fogs, the fight for Lookout Mountain was quickly dubbed the “Battle Above the Clouds.”

But on the Union left Sherman was having his difficulties. He had 26,000 men against 10,000 Confederates under Cleburne and Stevenson, but the geography favored the gray troops. When Sherman’s troops advanced early on November 24 they found that their initial objective was not part of Missionary Ridge as they were led to believe; instead, it was a spur separated from the main slope by a boulder-strewn ravine.

When attacking, Sherman’s bluecoats would have to descend from the hill they occupied, cross the ravine, then clamber up steep slopes against an enemy who were dug in behind log-and-earth breastworks. It was a formidable task, because through most of their advance they would be under heavy Confederate fire. Nevertheless Sherman’s veterans surged forward with real elan, though casualties were heavy.

But the defense showed courage, too, and the Federals were unable to dislodge them from their breastworks. After heavy fighting, the Union Army of the Tennessee’s offensive was stopped dead in its tracks and Sherman sent a message to Grant that his men could do no more. Grant told him to attack again.

Sherman followed orders, but when this new attack failed, he decided he was not going to waste any more lives. Taking out a cigar, he lit it, inhaled deeply twice, then turned to an aide and ordered the troops to entrench. The word went out that they were to hold their ground, but make no further attacks for the time being. Grant grew worried that Sherman might be forced back, and Sherman was the linchpin to his whole plan. There was a chance that Bragg would send more troops to the right, thereby making Sherman’s position untenable.

But if Grant ordered a diversionary attack on the Confederate center at Missionary Ridge, Bragg might focus on the new threat and forget Sherman, at least for a time. Grant lacked confidence in Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland, and suspected that its defeat at Chickamauga had destroyed its morale; nevertheless, he had little choice but to employ it and what he had in mind was a limited offensive that was not going to take any risks.

Thomas and his men were to take the Confederate rifle pits at the base of Missionary Ridge and then await further orders. Grant was thinking of a diversion, not a major offensive, but for once he misjudged the temper of his men. The soldiers of the Army of the Cumberland knew of Grant’s opinion of them and resented it. Feeling a bit ostracized, they wanted to show their mettle and also wipe out the memory of their embarrassing defeat in September. They could hardly wait to be unleashed on the enemy; one of the soldiers, an Indiana man, later admitted “we were crazy to charge.”

This advance was no hodgepodge run, but a carefully executed military maneuver. The serried blue ranks were spaced with parade ground precision, and as they moved off drums beat and regimental bands played martial tunes. The Confederates atop Missionary Ridge could only watch with barely concealed awe. This included Bragg whose headquarters was situated on the crest of the ridge.

Such an assault on a well dug in enemy, an enemy that also has the high ground, is usually considered suicidal. But Bragg was unfamiliar with defensive warfare and had unwittingly committed several grievous errors. He sent half of each regiment to rifle pits 200 yards from the base of the ridge, while posting the rest on its crest. The lower pit troops were to fire one volley, then climb back up the hill to join their comrades at the crest.

Even worse, the Confederate engineer was incompetent, foolishly placing the artillery on Missionary Ridge’s true crest, not the so-called military crest, which was the elevation that commanded the maximum field of fire down the slope. The military crest, which was a few yards further down, would have given gray gunners a clear field of fire, free of the natural dips, swells, and assorted rocks that would give Yankee soldiers cover.

Nonetheless, it seemed it was going to be the Federals, much like Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, performing a heroic advance that was doomed to bloody failure. But then a miracle occurred. Thomas’ Union troops easily took the lowest line of trenches with little loss. In keeping with the original scenario, they were supposed to stay there. But they began to receive fire from the second line of Confederate trenches halfway up the ridge, and they found this completely unacceptable. Rather than passively take Confederate fire like sitting ducks, the Federals spontaneously renewed the attack.

With the adrenaline pumping in their veins, cheer after cheer spontaneously bursting from their lips, the bluecoats pressed up the slopes, taking the second lines of trenches as they went. The Confederates were shocked by the blue tidal wave that engulfed them, and began to panic. Some started to go back voluntarily, remembering Bragg’s fire and retire order; but others, not having received that order, only saw retreat and followed suit.

The story of Lieutenant Arthur MacArthur of the 24th Wisconsin captures some of the spirit of that moment. Regimental standard bearer was a very risky occupation, since carrying the flag made you a natural target, and there was always the chance you would be killed by an enemy trying to seize the flag as a trophy.

As the 24th Wisconsin surged up the slope, two of its standard bearers were killed in succession. Who would take the precious banner? MacArthur stepped forward without hesitation, and bore the flag all the way up to the summit. His heroism earned him a Medal of Honor, and later inspired his son, General Douglas MacArthur.

The panicked Confederate retreat soon became a rout. Bragg tried to rally the men. “Here’s your commander,” he shouted. But the fleeing soldiers showed their contempt by answering “Here’s your mule!” As they fled, the Confederates cast off knapsacks, muskets, and blankets to lighten their load and hasten their escape. Only Cleburne’s troops, the ones who had successfully stalled Sherman’s advance on the right, withdrew in good order.

By contrast, the triumphant bluecoats, by that time in complete possession of Missionary Ridge, celebrated their success with great enthusiasm. Some shouted, some wept, and others danced with delight. Still others, mindful of this sudden reversal of fortunes, shouted in revenge, “Chickamauga! Chickamauga!” at the fleeing Confederates.

“Our men pursued the fugitives with an eagerness only equaled by their own to escape; the horses of the artillery were shot as they ran; squads of Rebels were headed off and brought back as prisoners, and in 10 minutes all that remained of the defiant rebel army that had so long besieged Chattanooga was captured guns, disarmed prisoners, moaning wounded, ghastly dead, and scattered, demoralized fugitives,” wrote a Union soldier from Kansas, adding, “Missionary Ridge was ours.”

Indeed, the Chattanooga fight had been costly for both sides. The Union suffered 753 dead and 4,722 wounded of 56,000 troops, while the Confederates had 361 dead and 2,160 wounded of 44,000 troops.

Although much hard fighting was to come, the Chattanooga campaign can be considered, along with Gettysburg and Vicksburg, another major turning point in the Union’s favor. The victory confirmed Grant as the Union’s greatest general. President Lincoln promoted him to Lieutenant General of the Army on February 29, 1864, giving him command of all Union forces. With Chattanooga, the gateway to the Deep South in Union hands, the Confederacy was in grave peril. The capture of Chattanooga set the stage, in 1864, for both the fall of Atlanta and Sherman’s March to the Sea.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments