By John E. Spindler

It is not always the actions of the brave and mighty that determine a battle’s outcome—victory or defeat can hinge on the most mundane of events. On December 10, 1899, one such occurrence, resulting in a severe British defeat, took place on a hill called Kissieberg near Stormberg Junction in the Cape Colony.

A Boer soldier suffering from diarrhea was preparing to relieve himself in the pre-dawn hours, when he noted glints off bayonets. After watching for a moment, he recognized the men as British. The soldier’s call for alarm brought forth a 60-man detachment from the Orange Free State’s Smithfield Commando stationed upon a nearby hill. Shortly afterwards, the British soldiers found themselves under intense fire.

“It did not take us a moment to realize that speed would be our only means of salvation,” wrote Pieter Kritzinger, a Boer soldier in the Rouxville Commando at Stormberg. Soldiers raced to the higher parts of the rocky hill, known locally as a “kopje,” and dug in before the British, commanded by Maj. Gen. Sir William Gatacre, could climb the hill’s more scalable part.

The Boers, led by Commandant Hans Swanepoel, opened fire from their positions at the top of the hill at 3:45 a.m. When they did so, the 7th Royal Irish Rifles rushed forward. Some went left and seized a smaller kopje, while most British infantrymen went to the right and had their momentum abruptly halted by a sheer cliff.

Drastically outnumbered, the soldiers of the Smithfield Commando detachment, supported by one Krupp howitzer, found themselves facing a 2,600-man attack force supported by a dozen Armstrong 15-pounder guns. After an exhausting night march in which the British force lost its way, Gatacre had planned to retake the Stormberg railway junction at first light via a surprise attack. But his battle plan went wrong at every stage.

The engagement at Stormberg Junction during the Second Boer War continued a long history of recorded conflicts in South Africa since the first Europeans arrived in the region in the mid-17th century. Jan van Riebeeck of the Dutch East India Company founded Cape Colony at Table Bay in 1652. The colony, which the Dutch established as a place for their ships traveling to and from the East Indies to resupply, existed in relative isolation until the French Revolutionary Wars.

British forces in 1795 seized Cape Colony from the Netherlands, but they returned the territory to the Dutch in 1802. Fearful that France would seize control of Cape Colony, a British expeditionary force took control of it again four years later. The Netherlands formally ceded Cape Colony to Britain in 1814.

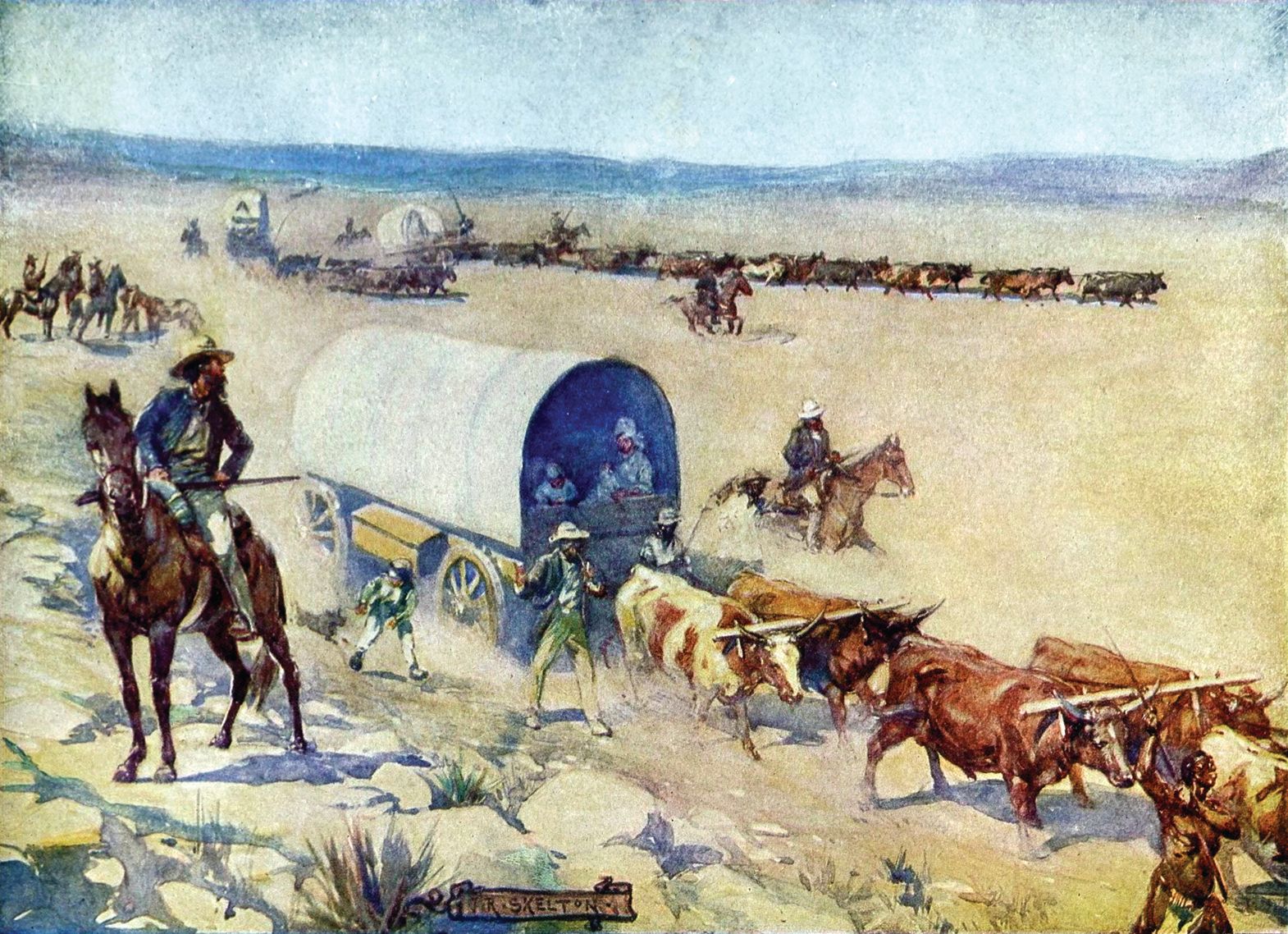

Dissatisfied with British colonial rule, a large number of Boers pioneers began migrating north of Cape Colony in 1837 to settle in the high veld. The mass migration of Boers that followed became known as the Great Trek. Britain recognized the independence of the Boer republics known as the Transvaal Republic and the Orange Free State, respectively, in 1852 and 1854.

A fragile peace in the region continued for another quarter century until the British, taking advantage of financial difficulties of the Transvaal government, annexed the republic in 1877.

Tired of Britain’s policy of aggressive territorial expansion in South Africa, the Boers declared their independence on December 16, 1880, sparking the First Boer War. Four days later, at Bronkhorstspruit, Boer irregulars routed a similarly sized column of British troops. Underestimating the military capabilities and mobility of their enemy, Britain suffered loss after loss in the field and had some of their frontier forts besieged. Attempts to relieve these Boer sieges resulted in three major defeats in the span of one month. The battle at Majuba Hill on February 27, 1881, proved to be a particularly disastrous defeat for the British army.

These losses forced Prime Minister William Gladstone to repeal the Transvaal annexation and seek a settlement with the Boers. The two sides subsequently entered into a peace known as the Pretoria Convention.

Relations between the Boer republics and Britain further worsened in 1887. The catalyst for the political friction was the discovery three years earlier of gold deposits along the Witwatersrand, a 35-mile long escarpment in the Transvaal. Additional discoveries of gold in the region followed, which sparked a gold rush.

Both Transvaal and Orange Free State already had experienced, with the earlier discovery of diamonds, what could occur with a large influx of foreigners. The Boers called these interlopers “uitlanders” and regarded them with great disdain. Fearing another attempt by Britain to completely control Southern Africa after the annexation of Zululand, Orange Free State’s President Marthinus Steyn signed an alliance with the Transvaal that included a mutual defense treaty by which the two Boer republics would come to each other’s assistance in the event of another war.

In a 10-year span from 1886 to 1896, the population of Johannesburg skyrocketed to 100,000 as British, Australians, and Canadians flocked to South Africa to seek their fortunes. Under Transvaal’s President Paul Kruger, the republic suddenly transformed from a poor, agrarian republic into the ranks of the world’s wealthiest nations. As a significant percentage of the new arrivals were British nationals, conflicts arose due to differences in wide range of subjects ranging from business practices to morality.

Despite the uitlanders’ contribution to the economic prosperity of Transvaal, they lacked political rights if they had not resided in the region for five years. While the gold prospectors, particularly the British nationals, did not want to relinquish their citizenship, many wanted to have the right to participate in the republic’s political process.

When mining magnate Cecil Rhodes became the prime minister of Cape Colony he saw the plight of uitlanders as a means to obtaining his goal of British imperialism in Africa. Rhodes found allies in London with the election of the Unionist Party and the appointment of Joseph Chamberlain, who shared Rhodes’s idea for British supremacy in Africa, to the post of colonial secretary. Because of these events, the Boers assumed that London wanted complete control of the states in South Africa.

Their fears were realized in January 1896. While working with a number of prominent, dissatisfied uitlanders, Rhodes contacted a Scottish friend, Leander Jameson, to help him reestablish British control of the Boer republics. Formulating a plan, which was secretly backed by Chamberlain, Jameson would launch a raid into Transvaal designed to promote and encourage an uitlander rebellion.

Jameson crossed the border into Transvaal on December 29, 1895, with 494 men, eight Maxim machine guns, and three light field guns. Word of the incursion spread rapidly and the Boers assembled a reaction force to stop the invasion. Setting out on January 1, 1896, Jameson’s force had advanced 20 miles when it stalled in face of a Boer detail that blocked the road to Johannesburg. After a brief, yet fierce, engagement that resulted in 30 casualties, Jameson surrendered.

The scandal resulted in Rhodes’ resignation as prime minster of Cape Colony. William Schreiner, a native of Cape Colony, succeeded him. Rhodes’s influence was not totally erased since an ally, Sir Alfred Milner, was appointed High Commissioner for Southern Africa. Milner strongly shared Rhodes’s view of British imperialism in Africa and devoted time and effort into how to achieve this goal.

Boer presidents Steyn and Kruger renewed the mutual assistance treaty between the two republics in 1897. German Kaiser Wilhelm II sent a telegram to Kruger congratulating him on thwarting the raid. Seeing a golden opportunity to strengthen his nation, Kruger entered into a strategic relationship with Germany. Kruger intended to use the revenue generated from Transvaal gold to strengthen his country’s defense. Pretoria bought the newest rifles and howitzers from Germany, but in order not to rely on just one source, it also purchased artillery from France.

Despite the apparent inevitability of another conflict, moderates on both sides made attempts to avoid bloodshed. The Bloemfontein Conference in spring 1899 was the last major diplomatic effort to resolve the tense political situation.

On September 8, 1899, Britain voted to increase the number of troops in the region by an additional 10,000 soldiers transferred from India and the Mediterranean. With these additional troops, the British were able to form a 47,000-strong 1st Army Corps in England for transfer to South Africa.

Kruger and Steyn responded with the construction of new forts along the frontier. In Transvaal, commandos were dispatched to the borders of Cape Colony and Natal. By that point, another Boer War seemed unavoidable.

Kruger, with Steyn’s support, dispatched an ultimatum to London on October 9 that set forth three key provisions. These were the withdrawal of British troops from the borders of Transvaal, the removal from South Africa all troops that had arrived since June 1, and the prohibition of any troops en route via sea to disembark in Southern Africa. Kruger further stipulated that if he did not receive British approval by 5 p.m. on October 11, then Transvaal and Orange Free State would consider a state of war to exist between Britain and the Boer republics. Colonial Secretary Chamberlain was delighted, as the Boers would initiate the war he desired.

Great Britain declined the ultimatum on October 11. Although many British officials felt the Boers would quickly submit, those in the charge of the armed forces were concerned that the number of British troops in South Africa was insufficient for the task at hand. When hostilities began in October, the British had just 22,500 men in South Africa, and more than half of those were stationed in Natal. As for artillery, the British had 60 field guns of various calibers.

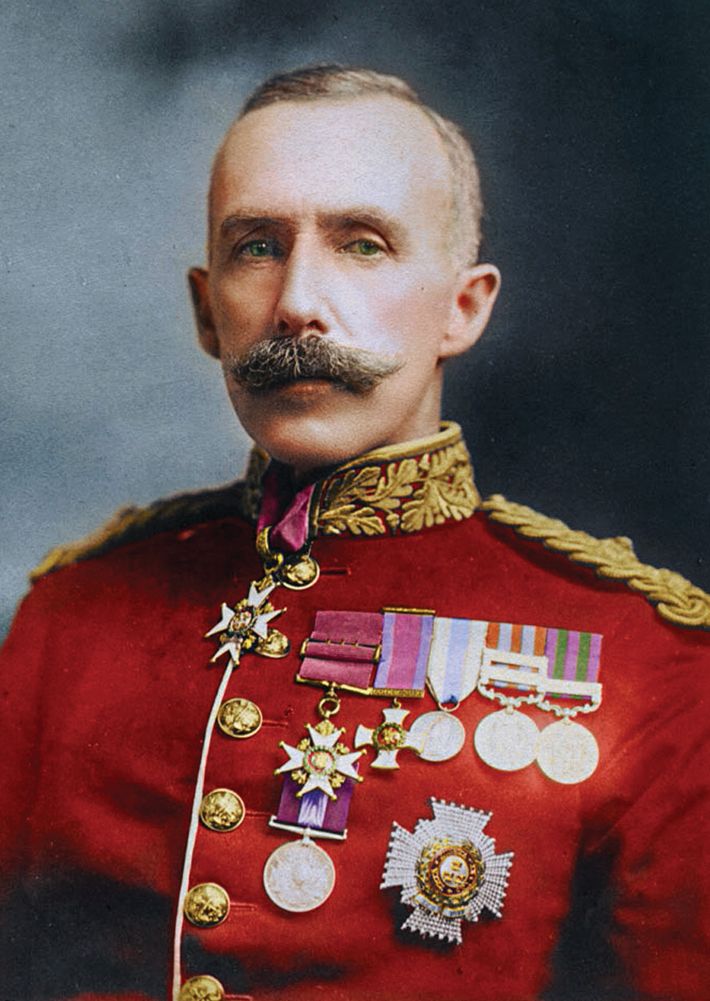

General Sir Redvers Buller 1st Army Corps comprised the 1st, 2nd and 3rd divisions. Elements of Gatacre’s 3rd Division would fight at Stormberg. The British distributed their mounted infantry and artillery brigades to support the infantry divisions.

The British forces that fought against the Boers were still essentially fighting the same style that they had successfully employed a century before in the Napoleonic Wars. With a succession of victories over native forces in Africa and India, the popular belief existed in the British military that no changes to tactics and strategy were required. While the Boers held the numerical advantage at war’s declaration, London believed that once the British Empire had mobilized it would be able to bring in men and equipment since the Royal Navy controlled the high seas.

One recent change in the British Army, though, was the replacement of the traditional scarlet jacket with a khaki-colored uniform. In a war in which Boer soldiers used guerilla-style tactics, the new khaki outfits would blend well in the reddish-brown terrain and arid climate of the veld.

The British Army had also begun updating its infantry weapons and some of the arriving units carried the new .303-caliber Lee-Enfield rifle with smokeless cordite ammunition.

But the majority of British troops still carried the .303-caliber Lee-Metford rifle firing black powder cartridges that produced clouds of tell-tale smoke. The Lee-Metford had a maximum range of 1,800 yards, but was most effective at less than 900 yards. For heavy fire support, each infantry, cavalry, or mounted infantry regiment received a pair of .303-caliber Maxim machine guns. Capable of firing 600 rounds per minute, these weapons similarly had a maximum range of 1,800 yards.

British soldiers in the Second Boer War were backed by mounted infantry and artillery. An artillery brigade consisted of six gun batteries. The horse artillery used 12-pounder field guns, while the field batteries were armed with 15-pounders. Although these were the most common, other calibers, such as the 7-pounder, were used as well.

Gatacre’s force at Stormberg suffered from some of the weaknesses that plagued the British. In addition to being outnumbered at the outset of hostilities, the British lacked accurate maps for the areas in which they intended to conduct operations. Apart from a handful of units that had been stationed in South Africa, the majority of the British forces that served in the conflict possessed limited knowledge of local topography and climactic conditions.

Upon arrival of the 1st Army Corps in South Africa, Buller developed an offensive plan to deal with current situation in Natal and Cape Colony. He originally intended to use Gatacre’s 3rd Division to force Boers that invaded the Cape Colony back across the Orange River. Additionally, he intended to use elements of the 3rd Division to secure key railway junctions in the colony.

But emergencies in other sectors sapped Buller’s strength. A significant portion of his division was taken away from him to contend with the Boer sieges of Kimberley, Mafeking, and Ladysmith, as well as to shore up British weaknesses in various hotspots in Natal.

Energetic and physically fit, 56-year-old Gatacre had seen action in Burma, India, and the Sudan. He habitually pushed the men under his command to the point that he overestimated their capabilities. While considered a so-called soldier’s general, the dictatorial way he drove his troops led them to give Gatacre the sobriquet of “Back-acher.”

At the beginning of the conflict, several Orange Free State commandos had begun operating in the area of the Stormberg railway junction. Commandant Jan Olivier, the vice chairman of the Orange Free State’s Volksraad, was the supreme commander of this force. Like many commandants, Olivier had no specific qualities to be leader. A large man over six feet tall, he was colorful, forceful, and greatly admired.

Commandant Jan Olivier of the Rouxville and Thaba Nchu commandos led the Boer force that crossed the Orange River and occupied Stormberg junction. Other Boer units operating in the area were the Bethulie commando under Veldcornet Floris du Plooy and the Smithfield commando under Commandant Hans Swanepoel. By the time Gatacre marched against the Boers occupying the area around Stormberg junction, the Boers had 760 Boer irregulars deployed to defend the position.

On October 12, the Boer force of 21,000 Transvaalers, under supreme command of Commandant-General Piet Joubert, and 15,000 Orange Free Staters had been mobilized for war. A large percentage of this force took the offensive and crossed the frontiers of Cape Colony and Natal.

While Joubert sent Assistant Commandant-General Piet Cronje and 7,000 Transvaalers and Free Staters to besiege Mafeking and the diamond center of Kimberley, he ordered another 14,000 Transvaalers and 6,000 Free Staters to cross at critical locations along the frontier. Within a couple of weeks, Boer forces besieged Kimberley, Mafeking and Ladysmith. Although a large number of British troops were surrounded, those sieges tied up a significant portion of Boer burghers and negated their advantages of numbers and mobility.

The first couple of battles, such as the clash at Talana Hill on October 20, were technically British victories, but the cost in casualties was high. While the Boers may have held a tactical advantage, it was a major strategic error to leave the region’s crucial railway junctions in the hands of the British—allowing them to deploy troops throughout South Africa.

The need to force the Boers to raise their sieges compelled Buller to scrap his initial plan. The 1st Army Corps arrived in South Africa on October 31. The very next day, the Orange Free State troops seized a key bridge over the Orange River at Norvalspont. But Steyn deliberately checked the advance of his republic’s commandos deeper into Cape Colony. He did this in the hope that a peace settlement might still occur. Once it became apparent that peace would not occur, Commandant Olivier advanced into the northeastern part of Cape Colony and secured the town of Aliwal North during the second week in November.

At Stormberg Junction, the 1st Berkshire Battalion had been stationed at the location long enough to build fortifications. Built in 1892, the junction guarded the East London to Bloemfontein railway. The Boers’ crossing of Orange River unnerved British authorities who ordered a withdrawal from Stormberg Junction. The Smithfield and Bethulie commandos did not occupy Stormberg until November 26. Olivier dispersed other commandos to secure the immediate area. Boer irregulars made excellent use of nearby kopjes and narrow valleys to form strong, natural defensive positions.

Gatacre, having seen his division reduced to the size of a brigade, arrived in the sector in early December. Impatient and seeking glory, he decided to liberate Stormberg using the town of Molteno as his staging area. Although a veteran officer, Gatacre had never fought the Boers. He decided to conduct a night march to get his troops into position for a dawn assault on the Boer positions in the hills surrounding the junction. Gatacre intended to make his attack on December 8, but once in Molteno he found that it took longer for the infantry and field guns to arrive at the staging area than he had expected.

Three routes led north from Molteno to Stormberg. The right route passed through gorges and kopjes and came out four miles east of the railway junction; the center route, which was the most direct, followed the railway to the junction; and the left route led eight miles west and would require a sharp turn to the east to reach the junction. Gatacre initially planned to advance on the most direct route.

At 4 a.m. on December 9, Gatacre’s men awoke and traveled by truck to Molteno where they were to board rail cars. Eight hours later the soldiers entrained, but were delayed by mules on the rail line. Rather than let the troops disembark, Gatacre forced the men to wait on the train for three hours in the blistering heat. In the meantime, Gatacre received intelligence, which later turned out to be false, that the Boers had deployed a strong blocking force astride his route of advance. Not wanting to undertake a night march through difficult terrain, he selected the left route.

When Gatacre left Molteno to retake Stormberg Junction, he had just one brigade composed of 2,600 soldiers. The brigade comprised the 2nd Irish Rifles Battalion, 2nd Northumberland Fusiliers Battalion, Cape Mounted Rifles, and two batteries of the Royal Field Artillery. Each infantry battalion possessed a Maxim machine gun. Other support elements included a Cape Police detachment, engineers, and a field hospital.

Owing to a mistake by a telegraph operator who forgot to transmit the message to the 1st Berkshires stationed 30 miles to the east at Penhoek, the battalion failed to arrive in Molteno. The battalion, which previously had been stationed in the Stormberg area, knew the terrain, and therefore would have been of considerable help. Unaware of the mistake, Gatacre did not understand why the 1st Berkshires had not arrived.

Although he failed to reconnoiter the route, Gatacre obtained the services of two Cape Colony policemen, who insisted they knew the area, as guides. The plan was to depart at 7:15 p.m., but the last of the troops did not arrive in Molteno until 8 p.m.

In spite of the lack of food and sleep, Gatacre ordered the troops to fix bayonets. They departed Molteno at 9:15 p.m. with the 2nd Irish Rifles leading the column. Behind the infantry battalions followed the artillery and mounted infantry. The rear of the column, which included the field hospital and the Irish Rifles’ Maxim gun, did not know the route had changed. For that reason, they marched up the main road, but they soon returned to Molteno.

Olivier, who was with his troops in Stormberg, knew the British were on their way, but he did not know when they would arrive or from what direction they would launch their attack. While Gatacre was gathering his force at Molteno, the 300 men of du Plooy’s Bethulie Commando and the 400 men from Burgersfort under Commandant Piet Steenkamp marched out of Stormberg and deployed on the Stormberg-Steynsburg Road. This left the 400 men of the Rouxville Commando and 290 burghers of the Smithfield Commando to defend Stormberg Junction. In addition, a detachment of 60 men from the Smithfield Commando deployed west of the town on a kopje overlooking Klipfontein, a farm owned by Louis van Zyl.

Gatacre’s force had been marching up Steynsburg road for nearly three hours when it reached a rail line nine miles from Molteno. This meant that the column had missed the turn it was supposed to take to reach Stormberg. The column halted at 1 a.m. when Gatacre demanded to know the reason his troops were not on the proper course. A sergeant told him the guides had not erred; rather, they had decided to take a longer route to avoid rough ground that would hamper the movement of the field guns.

Gatacre ordered an hour’s rest for which his troops were grateful. Having been exposed to the searing heat during the daylight hours with no food and very little water, they were exhausted. What is more, they had to march with fixed bayonets, which put an extra strain on the men since they had to carry their rifles for a long distance at an awkward angle.

After 3 a.m. on Sunday, December 10, the Irish Rifles marching in columns of four led the brigade through a defile and into a valley just north of Klipfontein. Some of the famished British soldiers broke ranks in order to try to capture some of Van Zyl’s sheep.

It was while the famished men slaughtered the sheep that they were spotted by the Boer with diarrhea who had walked far out of camp to move his bowels. He had just lowered his trousers when he saw the glint of British bayonets. “Die kakies! Die kakies!” he shouted as he ran back to the camp to alert the burghers of the Smithfield Commando.

As the British approached the Boer positions, Van Zyl retrieved his rifle and began firing at the British soldiers slaughtering his ewes. Upon hearing the sounds of gunfire, the Rouxville Commando rode to investigate. The battle started about an hour later. Hendrik Coetzee, a Boer teenager who had quit school to join a commando, is believed to have fired the first shot of the battle. The 60 Boers of the Smithfield Commando moved into position quickly and began pouring a hot fire into the head of the British column. The alarm had been sounded, and all of the Boers in the area began to deploy to check the British advance.

Not once during the long march had Gatacre sent scouts ahead of the column to look for the enemy. For that reason, when contact was made it surprised the British as much as it did the Boers. Gatacre ordered the Irish Rifles to seize a kopje as the sun rose in the east. Unfortunately, only three companies of the battalion obeyed the order. The rest of the infantry paid no heed to any orders issued by Gatacre. Instead, they rushed to a slope to their right, which happened to be the location a Swanepoel’s burghers. Upon reaching the slope, they suddenly realized that it led to a vertical cliff. While pondering their next move, they came upon a bushman’s cave at the cliff’s base. Some of them Irishmen climbed inside the cave. Because they were in a state of complete exhaustion, some of them fell fast asleep.

Maintaining their composure under pressure, the gunners of the British artillery batteries maneuvered their guns to support the infantry. Yet they had difficulty sighting their fire because they were firing toward the rising sun. While moving their guns forward to go into action, one of the heavy field guns became stuck in a steep ravine or “donga.”

Some of the guns began firing upon the Smithfield Commando’s position without effect as the Boer irregulars had constructed well-protected defenses that made them nearly invisible to the enemy. Some bold soldiers attempted to climb the kopje, but they came under fire from their own guns because of the poor marksmanship of the British artillerymen and the blinding sunlight. A number of Northumberland Fusiliers tried to use a donga as a defensive position, but it proved too wide and did not protect them from Boer rifle fire.

Gatacre and his officers had no idea of the enemy’s strength, much less the location of his forces because they were so well hidden in the terrain. As the British situation began to deteriorate, Gatacre became increasingly desperate. He possessed enough presence of mind, however, to realize that if he could just reorganize his force then his plan of attack still might work.

The British soldiers rushing across the plain from the farm to the kopje under heavy fire faced a nearly insurmountable situation. Just over an hour into the firefight, Gatacre decided his best course of action would be to have his troops pull back to the far side of the valley and reorganize. As they attempted to withdraw, the mounted infantry could furnish them with covering fire. He therefore issued orders for his beleaguered infantry to pull back. During the withdrawal, the Boers’ sole field gun shelled the British infantry. Even though there was just one gun arrayed against them, the British artillery crews could not silence it.

With the battle almost over, the mounted Bethulie and Burgersdorps commandos arrived upon the scene. While du Plooy split his force for flanking attacks, Steenkamp believed that a portion of the British force was trying to encircle the recently arrived Rouxville Commando. The burghers dismounted and found positions to fire upon the British. The British infantry became increasingly demoralized by the fact that they were being shot at by an enemy they could not see.

The newly arrived Boer reinforcements made the British fear that they might become trapped, so Gatacre ordered a retreat to Molteno. The 11 remaining Armstrong guns kept up support fire until the last moment with the mounted infantry once again covering the withdrawal. Swanepoel ordered his detachment from the Smithfield Commando to rush the retreating British.

During the withdrawal, the British abandoned another field gun when it became stuck on the farm Klipfontein. After the battle, the Boers took possession of this gun, as well as the one that had earlier become stuck in the donga.

Gatacre was almost slain by friendly fire. While leading the rearguard, his own gunners fired upon him, mistakenly thinking he was a Boer. Shortly after Gatacre’s force retreated, the British troops trapped at the kopje base surrendered. “The battlefield was literally gray with dead and wounded,” wrote Boer burgher Jacobus Bosman.

The battle had lasted an hour and a half. Gatacre retreated by the direct route to Colenso and by 11 a.m. what remained of his brigade arrived in town after a long march in the heat. It was only then that he noticed that one-quarter of his force was missing. Dissolving into tears, he assumed the worst. Gatacre’s disastrous operation had cost his brigade 29 dead and 57 wounded. As for the 633 officers and men who had been left behind, when they discovered that their general had abandoned them they raised white flags and surrendered. The Bethulie burghers rounded them up and took them into captivity.

Like previous encounters, the Boers chose not pursue the beaten enemy. Du Plooy and Steenkamp were keen to do so, as was Commandant Olivier initially; however, he countermanded the order, citing it was the Sabbath. Although a heated discussion ensued between Olivier and du Plooy, a pursuit would have been unlikely as many of Boer irregulars focused on recovering the abandoned British weapons. Of the approximately 800 burghers who saw action that day, only six Boers were killed and 27 wounded, one of whom was Commandant Swanepoel.

Gatacre told his wife several days later that the defeat was entirely his fault. It was “a most lamentable failure, and yet within an acre of being the success I anticipated,” he said. “I went rather against my better judgment in not resting the night at Molteno, but I was tempted by the shortness of the distance and the certainty of success.”

Many factors contributed to the defeat at Stormberg. Gatacre, like many British officers, underestimated the capabilities of the Boers. For one, the Boers had known that an attack was imminent and had ample time to prepare for it. Moreover, Gatacre rushed into battle without waiting for all of the troops available to him to arrive. Specifically, he failed to wait for the Brabant’s Horse and the Cape Mounted Rifles to join the attack. Similarly, the telephone operator’s mistake meant that the 1st Berkshires did not participate in the operation. Most critically, Gatacre overestimated the physical capabilities of his men. They were incapable of conducting a night march through unfamiliar territory after having sat most of the day under a baking sun without food or rest.

The clash at Stormberg was the first in a series of embarrassing military defeats for the British from December 10, 1899, through December 17, 1899, that became known afterwards as “Black Week.” On December 11, the day after the Battle of Stormberg, Boer generals Piet Cronje and Koos de la Rey routed a British division at the Magersfontein south of Kimberley, inflicting 1,000 casualties on Lt. Gen. Lord Paul Methuen’s force.

The worst of the defeats of Black Week unfolded on December 15 when General Louis Botha’s Boer force defeated Buller’s army at Colenso in Natal. In that engagement, the British suffered 1,243 casualties and lost 10 of their 12 field guns. When Buller suffered defeat in another advance at Spion Kop on January 24, 1900, London sacked him as overall commander replacing him with Lord Frederick Roberts.

Following the string of defeats in December 1899, the British army undertook sweeping military reforms to improve its operations and modernize its weapons, communications, and reconnaissance capabilities. These reforms, coupled with better military leadership, ultimately enabled the British to defeat the Boers in 1902.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments