By Matt Broggie

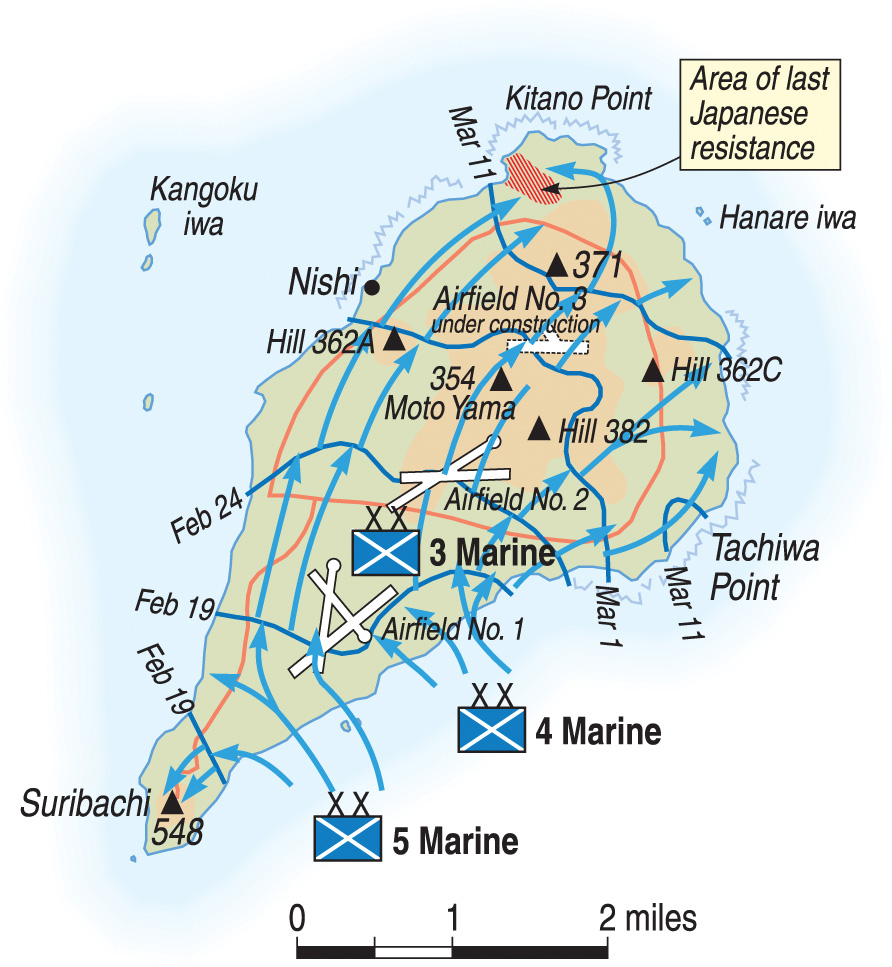

Sergeant Larry Kirby will always remember the fighting on the morning of March 12, 1945, as his unit, Easy Company, 9th Marines, 3rd Marine Division, attempted to move against Hill 362C under the cover of darkness in northeastern Iwo Jima. Frustrated with the slow progress being made on the heavily fortified Japanese island, divisional command had issued orders the day before to Easy and three other companies with depleted numbers from 3rd Marine Division to quietly infiltrate the Japanese line and then knock out a high-ground position being used as an observation post. It was known on Marine Corps maps as Hill 362C.

Kirby remembered he and his fellow Easy Company Marines were ordered to shed all unnecessary gear and carry only “a weapon, ammunition, water and a couple of rations in our pockets.” Kirby carried his preferred Thompson submachine gun and extra .30- and 20-round stick magazines loaded with .45-cal. ammunition. As a secondary weapon, he slung an M1 carbine around his back. To ensure complete silence, Kirby wedged a sock around the chain of his canteen to keep it from rattling.

The four companies met up at 3:30 am, and “then a silent command was given, just a nudge, and we started out.” Moving single file in complete darkness, each Marine kept formation by reaching out and touching the man ahead of him. For the past several days Kirby’s unit had advanced an average of 40 to 50 yards per day; on this morning, the column quickly covered 200 yards.

“This is a crazy idea,” Kirby thought to himself, “But, wow, it’s working.” As the column approached the high ground, the four companies split. Easy and Fox companies moved east on the right side of the position while the two other companies advanced northeast to make an attack on the left side of the hill. A parachute flare suddenly launched in the air and illuminated the region, betraying their stealthy approach.

“Machine guns opened up, and they began to annihilate us,” Kirby said. One hundred Marines from Easy and Fox ran for cover in a depression in the ground. Kirby saw piles of large rocks and steep stone walls around this low ground (likely a quarry the Japanese had been using to mine stones for constructing casemates) and took cover along the eastern wall. On top of the west wall overlooking the quarry, a machine gun fired into the Marines from the mouth of a cave.

“To the south there were machine guns that we had bypassed in the dark that were now turning on us,” Kirby recalled. Looking north, Kirby saw nothing that would offer protection. “So, the only thing we could do was to try to form into fire teams, but it was so disorganized that didn’t work. We simply had to go every man for himself and do our best.”

Some Marines managed to set up firing positions, but Kirby feared the Japanese would use the advantage of the high ground and get an angle on the fixed positions. “I thought my best bet was to keep moving. So, I would fire and cover, fire and cover.”

Trapped in what would be known as Cushman’s Pocket (named after 9th Marine Regiment commander Colonel Robert Cushman) for the next 38 hours, Kirby scavenged .45-cal. ammo from fallen Marines when his Thompson ran low, took sips of water from his canteen when given a chance, maneuvered and fired at Japanese soldiers, and tried to stay alive.

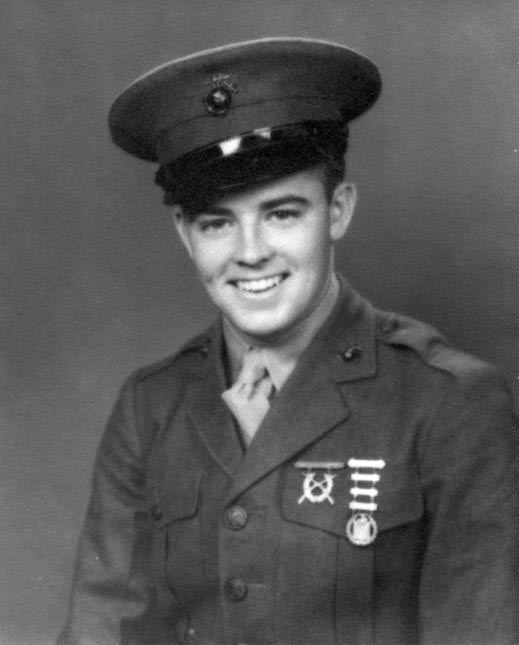

Like many World War II servicemen, Kirby felt compelled to enlist after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The 17-year-old from Brookline, Massachusetts, chose the Marine Corps because he liked the look of the uniform over the other branches. At the local recruitment office, the underage kid was turned away until he could get a parent’s signature. Kirby’s parents convinced him to wait until he was 18.

After his birthday Kirby enlisted and soon arrived at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in Parris Island, South Carolina. Twelve weeks of Marine boot camp instilled in him a pride that Kirby carries today. After completing basic training, he went through advanced infantry training school at Camp LeJeune and received training as a reconnaissance scout. From Camp LeJeune, Kirby went to San Pedro, California, for amphibious assault training. In the summer of 1943, he shipped out to the Pacific and arrived at Guadalcanal, where he was assigned to Easy Company, 9th Marines, 3rd Marine Division.

Even though the name “Guadalcanal” was embedded in American culture from the fighting there the year earlier, to Kirby “it was just another camp.” Training continued on the jungle island for the next few months. Practice maneuvers against simulated enemy fixed machine-gun positions were conducted at the fire team, squad, and platoon levels.

“This was a set procedure, and you practice it 25, 30 times,” Kirby recalled, “and then you do it 50 times until you know it inside-out. And then you do it another 50 times until that particular procedure becomes auto-pilot, muscle memory.”

As a recon scout, Kirby had the option of carrying a Thompson submachine gun or an M1 carbine. The carbine’s length felt awkward, so he favored the more compact Thompson. Kirby kept an eye out for a carbine with a folding stock, commonly used by paratroopers, but the rarity of finding a folding stock carbine “was like finding vanilla ice cream on Guadalcanal,” he lamented.

Equipped and fully trained, the 3rd Marine Division was assigned its first invasion against the Japanese-held island of Bougainville at the north end of the Solomon archipelago. As the island-hopping campaign progressed in the South Pacific, the airfield on Bougainville was a key objective. The night before the invasion, his nerves kept Kirby awake. The uncertainty of the day ahead weighed on his mind. He and some of his squad mates passed the time talking on the fantail of their ship.

At 4:30 am, November 1, 1943, the Marines began climbing over the side of the ship and down the cargo nets into landing craft known as Higgins boats. When the landing craft approached the island, Japanese guns opened fire. Remembering the experience, Kirby said, “I was scared to death … we were all kids.”

When the landing craft made it ashore, the Marines began pushing into the jungle and eliminating the Japanese defenders. In addition to fighting enemy soldiers, Marines battled the tropical island itself. “The jungle was so thick, if you couldn’t find a trail you had to chop your way through it,” recalled Kirby.

The weather also worsened the situation. Nearly every day, torrential rain soaked the Marines and turned roads into impassable mud swamps. Marines slowly expanded the beachhead and eventually secured the vital airfield. Army units relieved the Marines in mid-December, and the 3rd Division returned to Guadalcanal.

Recalling Bougainville and his first combat experience, Kirby said, “It was fierce. We lost men. I saw my first dead Marine…. It was a terrible place to be. I have no fond memories of Bougainville.”

After recovering from combat on Guadalcanal, the 3rd Marine Division began training for the next invasion scheduled in the island-hopping campaign. In June 1944, Kirby sailed for the Mariana Islands.

On June 15, 1944, the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions invaded Saipan. Kirby and the rest of the 3rd Division acted as a floating reserve aboard ships sailing offshore. As the Marine divisions and the Army’s 27th Infantry Division swept through Saipan and wrested the island from the Japanese, the 3rd Marine Division remained in reserve for five weeks. Recalling life aboard ship, Kirby said, “It was a lovely voyage … for the most part it was lazy days, enjoying the sun. Of course, in the back of your mind you’re always aware you’re not going on vacation. When you got off the ship it was going to be difficult.” The 3rd Division was never deployed to Saipan, and the Marine and Army units there secured the island on July 9. After resupplying on Eniwetok Atoll, the 3rd Division sailed to the southern Marianas to spearhead the assault against the island of Guam.

On July 21, Kirby and eight other scouts from his unit were tasked with a unique duty for the invasion. Three teams of three scouts, plus one officer, went ashore on Guam’s Asan Beach as pathfinders before the main invasion force. From lessons learned during the invasion of Bougainville, this pathfinder boat group would set up canvas markers on the beach to expedite the offloading of Marines from their landing craft and guide them off the beach in a safe direction.

Thinking back on his assignment, Kirby laughed, “Basically our job was: land on the beach, move into the brush, and if you see a defensive position, someone trying to kill you, send the guys the other direction … a very simple assignment.”

Kirby and the nine other Marines entered their landing vehicle, tracked (LVT), a landing craft fitted with tank treads to climb over the reef surrounding the invasion beach. Huge naval guns bombarded the island. Kirby watched with delight as massive shells passed overhead and exploded on the island. Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters and TBF Avenger bombers contributed by making repeated bombing and strafing runs against the beach. The single LVT approaching the shore did not attract fire from larger enemy guns, which feared revealing their positions and drawing American naval fire. Kirby recalled only sporadic small-arms fire as he hit the beach; one scout was shot and killed as he climbed over the side of the landing craft.

Kirby moved on, probed for enemy positions, and put up the canvas signs for the first wave of the invasion. “It cut down considerably on the casualties on the landing,” he remembered.

The first wave of the 3rd Division landed on Asan Beach soon after, destroyed the Japanese shore defenses, and slowly expanded the beachhead inland. Five days into the invasion, the Marine perimeter extended one mile from the beach to the base of Fonte Ridge, a section of high ground held by the Japanese that provided a dominating view of the American beachhead.

Around 3:00 am on July 21, the Japanese massed about 3,000 soldiers along the ridgeline and launched a suicidal banzai attack. Kirby was dug in on the Marine frontline when suddenly, “The Japanese came over the ridge in force,” he recalled. “There were so many of them they couldn’t be stopped; they ran through our line. It was crazy for a while. They actually penetrated our lines all the way back to the beach and got into the aid station and killed doctors and patients in their beds; they bayoneted them.”

The Japanese counterattack lasted about an hour, but order was soon restored. The Marines reorganized the line and collected any wounded Americans they could find. Kirby was shocked by the reckless and suicidal Japanese tactic. “It almost seemed as though they were not intent on accomplishing anything other than to get killed,” he said

Kirby’s most memorable moment of the banzai charge occurred as the fighting died down. A straggling young Japanese soldier—Kirby guessed he was 16—ran down from the ridgeline carrying explosives. Kirby watched from 30 yards away as the soldier charged one of the American artillery pieces but was knocked down by Marine rifle fire. The enemy soldier got back on his feet and limped toward his target only to get shot a second time.

“He got hit, went down, got up, got going, got hit, went down. I’ll bet he got hit six or seven times before he stayed down,” Kirby said. Badly wounded on the ground, the young soldier attempted to crawl to the American gun but was finally shot dead. Kirby marveled at the display of determination from his enemy.

Throughout the campaign on Guam, Kirby carried out his duties as a recon scout. Several days a week right before sunrise, Kirby dressed in specially designed jungle camouflage dungarees, covered his face with grease paint, and moved out ahead of the American front line alone. Creeping through the jungle, he reconnoitered the perimeter of the Japanese and tried to determine the size of the enemy force.

“I could tell from the positioning of the sentries in the [defensive] arc how big it was, whether it was a platoon or a company or bigger,” he remarked, “and usually, you could tell from where they placed them, which direction the unit would leave when they go out in the morning.” Kirby brought this information back to his captain, who radioed it to regimental command. Reports from scouts in every company were compiled, and they provided an invaluable picture of the battlefield that determined future unit movement across the island.

One morning while on a scouting mission, Kirby slowly made his way through the entangling jungle maze and suddenly made eye contact with a Japanese soldier 20 feet away. The two men were frozen in place as they stared at one another. Kirby saw an Arisaka 6.5mm bolt-action rifle in the high port position—pointed skyward and held close to the enemy soldier’s body. The moment seemed to drag on. Then the enemy soldier made the first move and quickly lowered the muzzle, shouldered the rifle, and pulled the trigger. The shot missed as Kirby instinctively dropped to the ground. Holding his Thompson at the ready, he heard the familiar “metallic click” of a Japanese grenade being armed against a steel helmet. The grenade landed behind Kirby, which caused him to jump out of his crouch, lunge forward and fire quick bursts at the soldier.

The grenade exploded and knocked Kirby down. When he looked up, the Japanese soldier was on the ground, leaning against a tree, shot in the chest, dead. The intimate encounter profoundly affected Kirby. He felt euphoric relief to still be alive, but taking the life of another in such a personal manner weighed on him heavily.

Before he left the scene, Kirby went through the dead soldier’s gear and found a Japanese flag with his family’s signatures on it. He placed the flag in the man’s hand. Kirby also found a photo of the soldier, which he placed in the lining of his own helmet—not as a souvenir, but as a way to honor the memory of the man he’d killed. After the war Kirby put the photo in his wallet, where it remained for over 70 years.

One of Kirby’s funniest memories of the war occurred sometime later, while he and other Easy Company Marines were on patrol in a coconut grove. As they pushed through the neatly planted rows of young palm trees, a Japanese gun opened fire, forcing the Marines to take cover. The ground had been trimmed of vegetation and offered no protection, so Kirby and his squad mates made themselves as thin as possible and hid behind the narrow tree trunks.

“We knew we’d have to make a run for it in one direction or another,” he remembered. Kirby’s friend George Christie, a corporal from New York, was standing sideways behind the next tree and yelled, “Hey Kirb, when we run, we should go in that direction.” Christie pointed to the thick jungle treeline bordering the grove. As he pointed, as Japanese bullet ripped through his wrist.

“He was in agony; he put his weapon down between his knees and put his back to the tree, holding that arm. I could see that he was in terrible pain,” Kirby said. Looking at Christie, Kirby wanted to give him a shot of morphine. “George, I’m coming over! Is there anything I can do?” he asked. Christie looked back at Kirby and replied, “I’m just glad I wasn’t taking a leak!” Kirby still laughs at the line from his friend today. “Some people go to great pains to develop a wound [to get out of duty]; here he’s got a very painful wound … it could be a permanent disability and he makes fun of it,” Kirby admired.

Organized Japanese resistance on Guam ended August 10, 1944. To Kirby, the 21 days of fighting on the island was a “satisfying experience.” He took pride in liberating a U.S. territory and restoring peace to the native Chamorro people. But as soon as the fighting had stopped on Guam, divisional command wasted no time training and preparing for the next invasion.

“Once in the Marine Corps they never let you stop moving [or] sit and think; we’re always doing something,” Kirby said. Field maneuvers took place for the next several months. Because the 3rd Division had so much combat experience, training focused on physical fitness over any specialized aspect of combat. Kirby and his friends wondered where the next invasion would take place, but it soon became obvious that they would land on an island called Iwo Jima.

Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers had been filling airfields throughout the Marianas in order to make bombing runs against the Japanese home islands. Looking at a map of the Pacific, Kirby saw that a round trip from the Marianas to Japan was about 3,000 miles, so it was clear that “we needed an airfield somewhere … and there’s Iwo Jima right in the middle.” Around this time Kirby was informed that he would no longer serve as scout and was transferred to conventional infantry. “There was no need for scouts on Iwo Jima. We didn’t have to locate the enemy—they were everywhere, like ants,” Kirby said.

General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, the Japanese commander on Iwo Jima, knew the strategic importance of the small island and its two functioning airstrips. For months, he had been preparing for the inevitable American assault. Hundreds of pillboxes and camouflaged gun emplacements dotted the island. Artillery pieces, mortar tubes, machine guns and sniper rifles had been sighted within concealed bunker apertures and cave openings. Mines had been placed along the beach and other likely routes of advance across the island.

Many of these hazards had been identified by U.S. intelligence, but what the preinvasion investigations failed to learn was that the enemy bunker system on Iwo was interconnected by a complex tunnel system that stretched for miles underneath the island. Kuribayashi’s headquarters sat five levels down, 70 feet beneath the surface. The defenders of Iwo Jima could easily move unnoticed from one position to another and also ensure that gun positions had a steady flow of ammunition. Mount Suribachi, an extinct volcano rising 550 feet on the southwest tip of the island, was honeycombed with internal stairwells and corridors, allowing the Japanese to move freely and take advantage of the elevation. Despite the months of pounding dealt by U.S. bombers, Iwo’s defenders were generally unaffected, sheltered in the island fortress.

Three Marine divisions sailed for Iwo Jima in February 1945. The 4th and 5th Divisions invaded the small volcanic island on February 19. The 3rd Division was again held in floating reserve offshore. Kirby thought, “It didn’t make sense. It’s an eight square mile island and [we put] two full divisions ashore; that’s 40,000 men. And there’s only 9,000 Japanese—that’s what [naval intelligence] told us beforehand.” Like many Marines tasked with invading Iwo, he believed the small island with the small force of Japanese defenders would be neutralized after a few days of fighting.

The intelligence report, however, had drastically underestimated the Japanese numbers. Instead of 9,000 defenders, the total was closer to 21,000; it would take the three Marine divisions 36 days to secure the island. Parts of the 3rd Division, including the 9th Marines, came ashore on the morning of February 23. The black sand beach was quiet by this point as Kirby marched past charred wrecks of tanks, trucks, landing craft, and other equipment—testimony to the vicious fighting that had taken place.

Iwo Jima’s landscape was in stark contrast to the jungles of Bougainville and Guam. Months of bombardment by U.S. bombers and the volcanic nature of Iwo created a barren, moonscape environment. Except for Mount Suribachi, the island looked flat, “like a pool table,” Kirby said. The 4th and 5th Divisions made little progress the first four days of the invasion. Advancing off the beach, Easy Company received small-arms fire from several directions, forcing the Marines to hug the ground or dash for cover.

“There was no safe place on Iwo Jima; every area was under fire at some time or another,” Kirby remembered. Around 11:00 am, as he looked out from the U.S. line, he heard a Marine say, “Hey, look at that.” Kirby rolled over on his back, looked toward Mount Suribachi, and saw Marines moving around its summit. He watched as an American flag was raised in place and flapped in the wind. The event has become an iconic moment of the Pacific War and the history of the Marine Corps, but at the time, Kirby explained, “That didn’t mean anything to me. All it meant was that now we won’t take any fire from behind us.”

Slow, excruciating progress took place day after day. Enemy soldiers made the Marines pay dearly for every yard gained. Easy Company came ashore with 225 men, but 12 days of combat reduced the company to 73. Fox Company, which fought alongside Easy, suffered similar losses. “So, we were really of no value,” Kirby said. “You train as a company, you train as a platoon, you train as a squad,” but after suffering such high casualties all unit cohesion was lost.

Easy company had become ineffectual. Divisional command formed the battered companies together and gave them the mission of infiltrating through the Japanese outer defenses under the cover of darkness and knocking out Hill 362C. The Japanese heard the column of Marines, sent up parachute flares, opened fire, and sent them running for cover in the nearby quarry. For the next 36 hours, Kirby and about 100 Marines fought for their lives trapped in Cushman’s Pocket.

Kirby dreaded sunrise. To the Japanese positioned around the rim of the pocket, daylight was their ally. Conversely, darkness brought moments of reprieve to the Marines and concealed their movements. Some Marines attempted to escape by darting between rock piles and depressions in the ground leading away from the area, but vigilant Japanese gunners cut them down.

Marine fire teams kept shooting to keep the enemy from charging into their position. A mortar round landed near Kirby, and the concussion of the blast knocked him off his feet. A rock gouged a hole in his back. The injury wasn’t serious; Kirby kept fighting. The Japanese were close enough that Kirby could hear them taunting the Marines during lulls in the shooting. He repeatedly fired, moved, and dug in. Hours into the fighting he forced himself to eat one of his D rations, even though he wasn’t hungry.

Kirby watched a Marine from Fox Company try to sprint out of the area only to have his legs blown off in an explosion. This chaos continued hour after hour as the Marines fought off any encroaching Japanese soldiers. After a day and half of fighting in the pocket, Marine reinforcements finally reached the location. Two Sherman tanks entered the area, one with a “short, stubby barrel—probably a flame-thrower,” Kirby recalled. “Seeing that [short barrel] the enemy soldiers didn’t fire at the tank because that flamethrower would have cremated them all.”

One Sherman provided cover while the other drove down into the quarry near Kirby’s location. The driver forced his tread onto a rock, elevating the bottom of the tank. The driver motioned Kirby and a few other Marines over as they crawled under the Sherman and up through a hatch near the bow gunner’s seat. With the Marines aboard, the tank crawled out of the pocket and back behind American lines. “In all, they rescued seven men from Easy Company and four from Fox Company. [Of the 100 marines] Only 11 came out,” Kirby said.

As one of the few survivors of Cushman’s Pocket, Kirby credited the lessons learned from fighting on Bougainville and Guam for saving his life. Kirby and the remnants of Easy and Fox companies were pulled out of the pocket on March 12, taken to a sandbag bunker, and given some food.

“We just sat there staring at each other; no one said anything,” he remembered. After the wound on his back was treated and bandaged, he was ordered to the beach to board a ship back to the Marianas. At the beach he stood in a line with other Marines, waiting for a landing craft to ferry them to a hospital ship. Exhausted and rattled from the ordeal of the past 36 hours, Kirby thought about his friends that were missing or killed, and he sobbed. The landing craft came ashore, and Kirby stepped off Iwo Jima.

Soon after Kirby was rescued from Cushman’s Pocket, a fresh battalion of Marines marched into the area to neutralize Hill 362C. Fighting in the pocket continued four more days. On March 16, all Japanese resistance in the area was eliminated, and the hill was finally in Marine hands. The fall of Hill 362C allowed the final push across the northern section of Iwo Jima to begin. The last Japanese soldiers were wiped out on March 26. A devastating cost in lives was paid to secure the island: 5,931 Marines and 209 Navy Corpsmen were killed in the 36-day battle. Nearly the entire Japanese force of 21,000 soldiers were killed, and just 216 were captured alive.

After some recuperation on Guam, Kirby began training for the invasion of Japan. He was told to expect 100 Japanese divisions to defend against the U.S. landings in the home islands. He knew his luck would not hold out any longer and that he would surely be killed in the invasion. On August 13, his unit’s message center received a coded transmission stating the Japanese Foreign Office had contacted Switzerland to coordinate a surrender.

The news spread rapidly throughout the 3rd Division. Kirby compared hearing the unofficial news of Japan’s surrender to holding five winning lottery numbers and waiting for the sixth. On August 15, the formal surrender was announced; the war was over. “It was the happiest day of my life,” Kirby recalled. No one knew the details of the atomic bombs dropped the week before.

“We had heard about [the bombs] but didn’t understand the severity or size,” Kirby remembered. “We just assumed they were some kind of giant blockbusters.” He boarded an LST (Landing Ship Tank) and began his journey home to Brookline, Massachusetts. After being away for three and one-half years, he arrived outside his house by taxicab at 8:00 pm on Christmas eve, 1945.

“There was a light snow falling and Christmas carols playing like a Norman Rockwell scene,” he remembered. “I rang the bell, my sister opened, and I said ‘Hey, I’m home.’” The reunion with his family was the “ultimate joy.”

Kirby wasted no time getting on with civilian life. Two weeks after his homecoming he enrolled in classes at Emerson College in Boston, where he met “the beautiful Mary Crane.” Eight weeks after their first date, they eloped to New York and got married on April 11, 1946.

Still happily married today, they will celebrate their 75th anniversary in 2021. Thinking back on his experience in the war, Kirby remarkably said, “Being on Iwo Jima was the best thing to ever happen to me…. I learned the value of love. These young Marines on Iwo Jima willingly gave their lives for their friends because they loved them. Thank you, Iwo Jima. I learned that lesson and I’ve followed it all my life.”

Matt Broggie earned a B.A. in History from California Lutheran University and an M.A. in Military History from Austin Peay State University. He teaches U.S. and World History at APSU and leads battlefield tours for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours. He lives in Nashville, Tennessee.