By Michael D. Hull

After six years of global destruction, suffering, and death, World War II was almost over in the Spring of 1945.

Much of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy lay under rubble, dictators Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini were dead, and a sinister collection of top Axis henchmen were in custody, awaiting Allied justice as war criminals. After mourning the estimated 50 million dead of World War II, the liberating nations rejoiced.

Flags fluttered brightly from windows as multitudes sang and danced in the streets of great cities from Paris to Brussels to San Francisco. In London, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill stood beside King George VI on the balcony of Buckingham Palace and told thousands of Allied servicemen and civilians, “This…is your victory.” World War II had become history—in Europe.

But thousands of miles away, the conflict continued in the Far East. There, British forces mopped up Japanese resistance in Burma, the Americans secured the Philippines and Okinawa, and Allied planners were readying an invasion of the Japanese home islands. While the enemy war cabinet stubbornly resisted Allied demands for unconditional surrender, fleets of powerful U.S. Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers continued to pound Tokyo and other cities.

And then, on August 6 and 9, atomic bombs were dropped on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively. Modern warfare’s first two ultimate weapons killed many thousands instantly and turned the two Japanese cities into smoking wastelands. The blinding explosions were to cast an ominous glow on the future of all mankind.

At 7 p.m. on August 15, 1945, reporters crowded into the Oval Office of the White House to hear America’s new president, the peppery Harry S. Truman, announce in his flat Missouri twang, “I have just received a note from the Japanese government in reply to the message forwarded to that government by the secretary of state on August 11. I deem this reply a full acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration, which specifies the unconditional surrender of Japan.” Broadcasting at midnight on August 14, Prime Minister Churchill had already declared, “Japan has today surrendered. The last of our enemies is laid low.”

After almost four years of humiliating setbacks, climactic naval battles, and bloody invasions from Pearl Harbor to Bataan, from Guadalcanal to Okinawa, the Pacific War—and World War II—had finally come to an end.

On Guam, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the silver-haired commander of U.S. naval forces in the Pacific, reacted quietly to the momentous news. He “didn’t get jubilant or jump up and down like I saw some other officers do,” reported an aide. “He merely smiled in his own calm way.”

Aboard his flagship, the battlewagon USS Missouri, off the coast of Japan, Admiral William F. Halsey, commander of the U.S. Third Fleet, responded differently. The jut-jawed, pugnacious “Bull” Halsey let out a loud “Yippee!” and slapped every shoulder within reach. After calming down, he ordered the hoisting of “well done” signals. Then, just to be on the safe side, and because of his legendary distrust of the Japanese, Halsey issued an order to his carrier pilots to “investigate and shoot down all snoopers—not vindictively, but in a friendly sort of way.”

On ships throughout Halsey’s fleet, whistles shrilled and crewmen hugged each other. “Every ship broke out its largest ensign,” said one officer,” and the men vied with one another to see who could yell the loudest.”

A large force of U.S. bombers and fighters was approaching Tokyo when it was notified to jettison its bombs and return to base. But the shooting was not quite over.

Five Japanese aircraft attacked the Third Fleet that morning and were quickly shot down by ships’ gunners. An additional 38 planes were downed on the last day of hostilities.

In the Japanese capital, the war cabinet resigned en masse after a broadcast by Emperor Hirohito, and General Douglas A. MacArthur, the supreme commander of Allied ground forces in the Pacific theater, radioed Tokyo that the Allied high command had accepted Japan’s surrender. A Japanese delegation was flown to Manila and informed that Allied forces were about to land in their homeland. The enemy officials were asked to provide details of their defenses, and they cooperated fully.

Forty-five C-47 transport planes touched down at the Atsugi air base shortly after dawn on August 28, and the Allied occupation of Japan began. The next day, the U.S. battleships Missouri and South Dakota and the Royal Navy battleship HMS Duke of York dropped anchor in Tokyo Bay along with hundreds of other warships of the Third Fleet and the British Pacific Fleet. The 35,000-ton Duke of York, a Home Fleet veteran of the invasion of North Africa and the pursuit of the German battlecruiser Scharnhorst, was wearing the flag of Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, commander of the British Pacific Fleet. The display of naval might awed Japanese observers on shore.

Admiral Nimitz arrived by flying boat on the afternoon of August 29. The usually calm and dignified seadog from Texas was seething over President Truman’s selection of the handsome, autocratic General MacArthur to conduct the planned surrender ceremony and oversee the occupation. Nimitz had no ambition to command the occupation, but he was annoyed at the Army taking the spotlight when he felt that the Navy and Marine Corps had borne the brunt of the Pacific War.

In Washington, Navy Secretary James V. Forrestal saved the day by proposing that the Japanese surrender be signed aboard the USS Missouri. Truman was delighted with the idea. The vessel had been named for his home state and christened by his daughter, Margaret, in January 1944. The fourth of the Iowa-class battleships, the 45,000-ton, 888-foot-long Missouri (BB-63) was laid down in the New York Navy Yard in January 1941, commissioned on June 11, 1944, and was the last battleship to enter service with the U.S. Navy. Mounting nine 16-inch guns, she screened Admiral Marc A. Mitscher’s Task Force 58, supported the invasions of Iwo Jima and Okinawa in February and April 1945, survived a kamikaze crash, and bombarded industrial centers in Japan.

The date set for the surrender ceremony was Sunday, September 2, 1945.

By August 30, more than 4,000 troops of Maj. Gen. Joseph M. Swing’s U.S. 11th Airborne Division had landed at Atsugi. They were there just in time to greet General MacArthur when his personal C-54 Douglas Skymaster transport, named Bataan, touched down at 2:19 PM that day. With a long corncob pipe clenched jauntily between his teeth, MacArthur stood silently at the plane’s door, savoring the moment. He muttered, “This is the payoff.”

Then the smiling MacArthur strode down the landing ramp to shake hands with Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger, a decorated veteran of the 1918-19 Siberian campaign, capable commander of the U.S. Eighth Army, and liberator of New Guinea and the Philippine Islands. “Bob,” said MacArthur, “from Melbourne to Tokyo is a long way, but this seems to be the end of the road.”

September 2 dawned cool and gray in Tokyo Bay. Around 7:30 AM, an American destroyer lay to, and a host of correspondents and photographers from a score of countries clambered aboard the USS Missouri to take up assigned positions. The Russians were obstreperous, observed one of the ship’s officers, and roamed around the battleship “like wild men.”

The “Mighty Mo” was especially rigged for the occasion, and at morning colors the Stars and Stripes was hoisted on the mainmast. It was the flag that had flown above the U.S. Capitol on December 7, 1941. Mounted on a nearby bulkhead was another American flag—a tattered one bearing 34 stars. This was the ensign that Commodore Matthew C. Perry had flown aboard his flagship, the USS Powhatan, when he sailed into Tokyo Bay in 1854 to open Japan to the West. Admiral Halsey had ordered Perry’s flag rushed from the U.S. Naval Academy Museum in Annapolis, Maryland, for the surrender ceremony.

The destroyer USS Buchanan pulled alongside the starboard side of the USS Missouri at 8:03 AM and discharged high-ranking Allied officers, including Admiral Halsey, General Eichelberger, Dutch Admiral C.E.L. Helfrich, Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell, General Carl A. Spaatz, Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney, British Lt. Gen. Arthur E. Percival, and Lt. Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright. Percival and Wainwright had been interned in Manchuria since the surrender in 1942 of Singapore, Bataan and Corregidor. At 8:05 AM, Admiral Nimitz arrived in a motor barge and was piped aboard. A few minutes later, General MacArthur, pale and unsmiling, climbed aboard from the destroyer USS Nichols and walked to Admiral Halsey’s cabin.

He surveyed the officers aboard the battleship, shook hands with Nimitz and Halsey, and commented, “It’s grand to have so many of my colleagues from the shoestring days here at the end of the road.” Besides 43 high-ranking officers from eight Allied nations, MacArthur was heading an impressive U.S. delegation of 89 officers that included 39 generals and 34 admirals. Among them were Lt. Gen. James H. Doolittle, whose famous B-25 bomber raid had first carried the war to Japan in April 1942, and Maj. Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, whose Twentieth Air Force had rained final devastation on the Japanese.

Another officer present was the short, slightly-built Vice Adm. John S. “Slew” McCain, a carrier task force commander who had distinguished himself by his vigor and audacity in the Marianas, Philippines, Okinawa, and China Sea campaigns. Worn out by the war and with his weight down to 100 pounds at the age of 61, he had requested home leave, but Admiral Halsey pressed him to stay for the surrender ceremonies. McCain died four days later at his home in Coronado, California.

Conspicuously absent from the gathering was the quiet, taciturn Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, victor of the Battle of Midway and commander of the U.S. Fifth Fleet. He was stationed off Okinawa aboard his flagship, the battleship USS New Jersey, because Nimitz had wanted someone to take command in the Pacific in case Japanese fanatics attacked the Missouri. Fears had been expressed that kamikaze suicide planes might be launched against the Mighty Mo when she entered Tokyo Bay.

Eleven Japanese delegates arrived at 8:56 AM aboard the destroyer USS Lansdowne, named for Lt. Cmdr. Zachary Lansdowne, who was killed in the tragic crash of the Navy dirigible, Shenandoah, on September 3, 1925. Following Colonel Sidney Mashbir, General MacArthur’s chief translator, Japanese Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu made his way painfully up a gangway to theMissouri’s quarterdeck. His left leg had been blown off by an assassin’s bomb in Shanghai years earlier, and his artificial leg caused him agony. The civilian Japanese representatives wore formal morning cutaway coats and top hats in contrast to the ill-fitting uniforms of the military delegates and to the khaki uniforms and open-necked shirts worn by General MacArthur and the U.S. Navy and Army officers. There was an eerie silence as the 11 Japanese delegates took their places on deck.

prisoner in the Philippines and at Singapore respectively, look on. A host of Allied officers observes the proceedings from a few feet away.

By now, the battleship was crammed with delegates and onlookers. More than 100 Allied generals and admirals were on the main deck, while reporters and the ship’s complement of 3,000 officers and bluejackets watched from atop the big 16-inch gun turrets and wherever else they could find space. All knew they were witnessing a historic moment, and the tension was immense.

The Japanese military and civilian envoys walked in front of a battered mess table on which the surrender documents had been strategically placed to cover coffee stains on the green felt. The Royal Navy had offered an elegant mahogany table used in one of Admiral Sir John R. Jellicoe’s dreadnoughts at the Battle of Jutland on May 31-June 1, 1916, but it was considered too small for the occasion. Accompanied by Admirals Nimitz and Halsey, General MacArthur walked briskly across the Missourideck to the table. All eyes were on the Japanese.

“We waited a few minutes, standing in the public gaze like penitent schoolboys awaiting the dreaded schoolmaster,” reported Toshikazu Kase, a Japanese delegate. “A million eyes seemed to beat on us like arrows barbed with fire. I felt them sink into my body with a sharp physical pain.”

The ship’s chaplain delivered an invocation, a recording of the Star-Spangled Banner was played over the public address system, and scrawny Generals Percival and Wainwright stepped to MacArthur’s side behind the table, facing the Japanese. “We are gathered here,” MacArthur intoned slowly, “representatives of the major warring powers, to conclude a solemn agreement whereby peace may be restored…”

His hands shaking, the presiding general continued, “It is my earnest hope, indeed the hope of all mankind, that from this solemn occasion a better world shall emerge out of the blood and carnage of the past, a world founded upon faith and understanding, a world dedicated to the dignity of man and the fulfillment of his most cherished wish for freedom, tolerance, and justice.” Almost as if on cue, the clouds parted, and the sun emerged for the first time that morning. In the distance, the snow-clad peak of Mount Fuji sparkled.

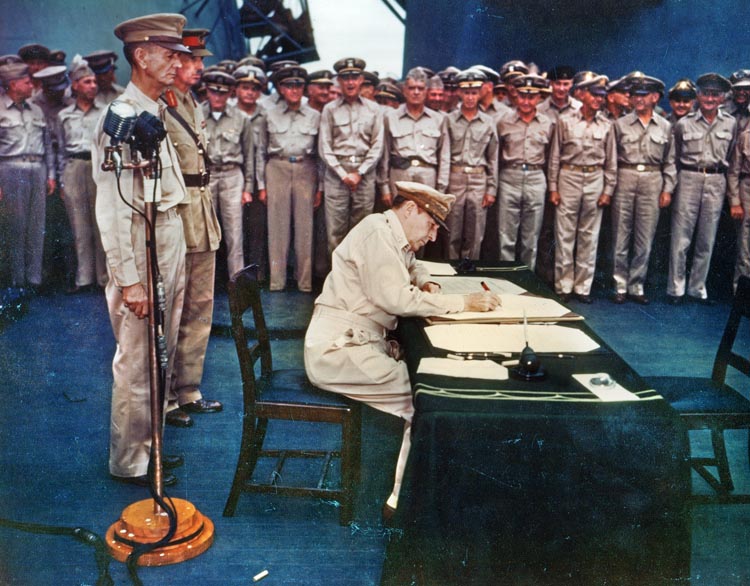

General MacArthur stepped back and motioned for Foreign Minister Shigemitsu to sign the surrender document. He limped forward and sat at the table. He removed his yellow gloves and silk top hat and placed them on the table. Shigemitsu stared at the paper for several moments, fumbling nervously with his cane and giving the impression of stalling. But MacArthur realized that the foreign minister was confused and said sharply to his chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Richard K. Sutherland, “Sutherland, show him where to sign.” Shigemitsu signed.

Next, General Yoshijiro Umezu, the Japanese Army chief of staff, marched forward, signed the document quickly, and walked back stiffly to his country’s delegation. Then it was MacArthur’s turn to sign for the Allies. Using three pens, he wrote his signature a few letters at a time. He handed the first pen to General Wainwright, whom he had left in charge of the doomed garrison at Corregidor in March 1942, and the second to General Percival, who had surrendered the bastion of Singapore to the Japanese in February 1942. MacArthur put the third pen into his pocket to take to his wife, Jean, and son, Arthur, in Manila.

Admiral Nimitz signed on behalf of the United States, and then the other Allied representatives signed for their respective countries: General Hsu Yung-chang for China, Admiral Fraser for Great Britain, Lt. Gen. K. Derevyanko for the Soviet Union, General Sir Thomas Blamey for Australia, Air Marshal Sir L.M. Isitt for New Zealand, Colonel L. Moore-Cosgrove for Canada, Admiral Helfrich for the Netherlands, and General Jacques Philippe Leclerc for France. His famed Free French 2nd Armored Division had liberated Paris in August 1944.

According to reporter Edgar A. Poe of the New Orleans Times-Picayune, “Halsey, known for his salty language as well as for his brilliant naval strategy, moved his lips constantly during the surrender ceremonies. He was apparently still cussin’ the enemy.”

After the signings were completed at 9:25 AM, General MacArthur said, “Let us pray that peace now be restored to the world, and that God will preserve it always. These proceedings are now closed.” Accompanied by Generals Wainwright and Percival, he then walked toward Admiral Halsey’s cabin without casting a glance at the Japanese delegates. MacArthur put his arm around Halsey’s shoulders and asked, “Bill, where in the hell are those airplanes?” There was a roar in the distance, and then 1,900 Allied bombers and carrier fighters swept over the Missouri in a thunderous salute.

Verne F. Harrington of Adams, Massachusetts, a 20-year-old seaman first class, noticed the reaction of one of the Japanese delegates when the planes flew overhead. “You could see him looking up at them and smiling,” he said. “I guess he knew they meant business.”

Graham Stanford of the London Daily Mail was also watching the Japanese representatives as they were led away. “They looked up at the sky, whispered among themselves, and then they were gone, the destroyer rushing them back to their ruined city,” he reported. “The war was over, and now all the world was at peace. But there was no cheering or laughing, and little talking, for every man felt the gravity of this occasion.”

After the surrender ceremony, MacArthur left the deck for another microphone to broadcast an eloquent message of both hope and warning to the American people. “Today, the guns are silent,” he said. “A great tragedy has ended. A great victory has been won. The skies no longer rain death, the seas bear only commerce, men everywhere walk upright in the sunlight. The entire world is quietly at peace. The holy mission has been completed…A new era is upon us…We have had our last chance. If we do not devise some greater and more equitable system, Armageddon will be at our door…”

Six days after the surrender ceremonies, General MacArthur went to Tokyo. MacArthur, who had gallantly led the 42nd Infantry (Rainbow) Division in World War I, served as West Point superintendent, acted as military adviser to Philippine President Manuel Quezon, risen to Army chief of staff, and commanded Allied ground forces in the Pacific theater in 1941-45, now became the civil administrator of Japan. During his tenure from 1945 to 1951, he earned high praise for his enlightened reforms of the defeated nation’s political, economic, social, and cultural life.