By Mike McLaughlin

The Pearl Harbor disaster presented the U.S. Navy with a sobering question: how to recover? More than 2,000 men had died. Nearly half as many were wounded. Eighteen ships were damaged or sunk.

“The scene to the newcomer was foreboding indeed. There was a general feeling of depression throughout the Pearl Harbor area when it was seen and firmly believed that none of the ships sunk would ever fight again.” This was a haunting sentiment from Captain Homer Wallin, the man who would lead the salvage effort.

Admiral Chester Nimitz, named Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC) days after the attack, flew to Hawaii to take command. He landed in Pearl Harbor on Christmas Day. His briefings had prepared him, or so he thought. Awestruck, he remarked, “This is terrible seeing all these ships down.” The ceremony installing Nimitz as CINCPAC was held on the deck of the Grayling, a submarine he had once commanded. Cynics commented that it was the only deck fit for the ceremony.

The days of the Battleship Navy were over. The Japanese made the point again on December 10, sinking the British battleship Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser Repulse off Singapore. Nimitz’s aircraft carriers were now the heart of his strategy. Yet with proper escort, the battleships could still be effective weapons. If they could be saved, Nimitz would give them work.

The salvage effort began on December 7 when crews manned hoses to fight the fires while the attack was still under way. These firefighters were aided by boats, tugs, and even a garbage hauler. Men from the fleet’s base force brought pumps to battle the flooding. Rescue teams searched for sailors trapped in the capsized battleships Oklahoma and Utah.

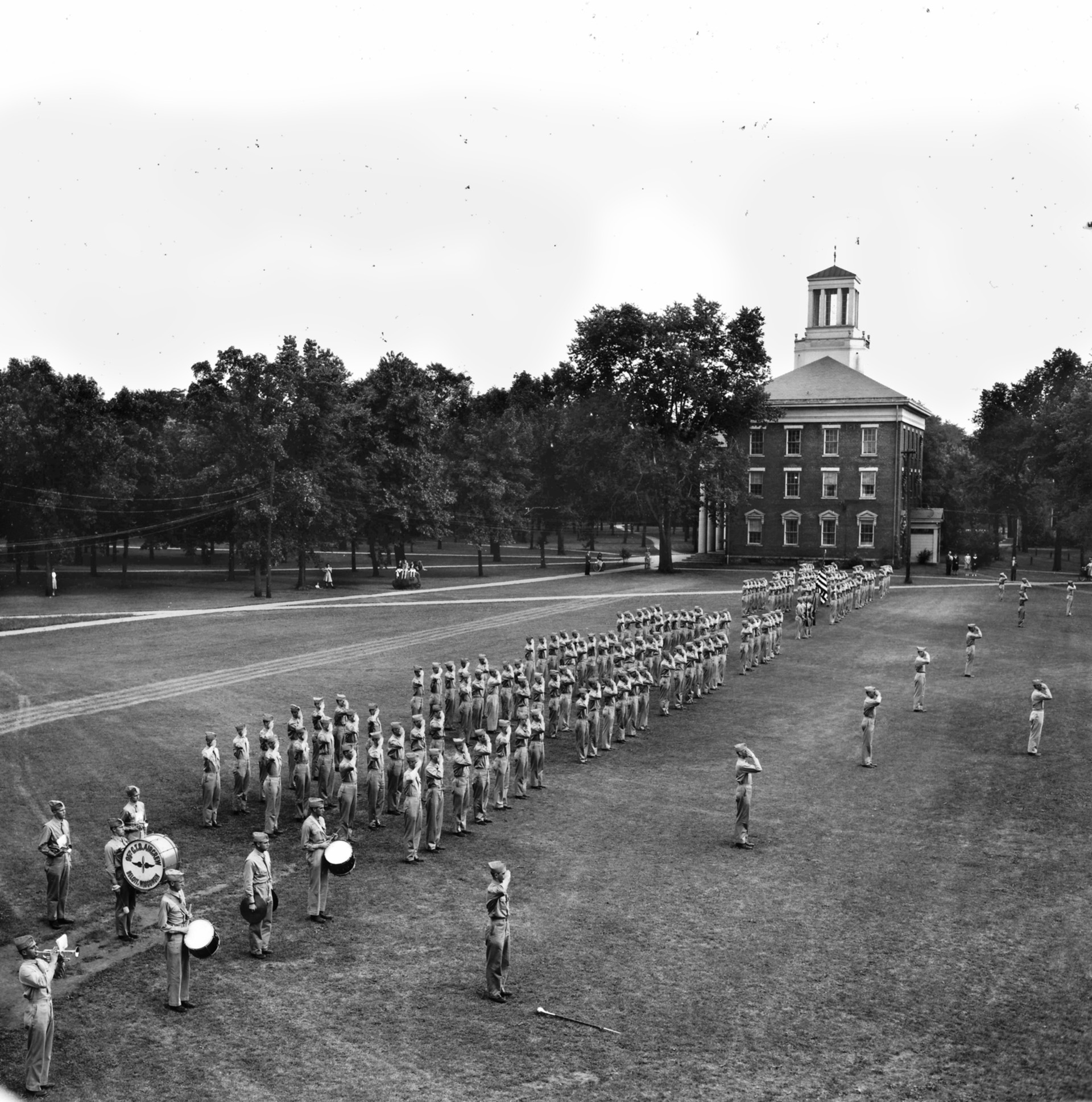

On January 9, 1942, Captain Wallin took charge of the Salvage Division, itself a new branch of the Navy Yard. A native of Washburn, ND, Homer Wallin had spent half his life training for this. Like many men raised far from the sea, he sought a naval career. He went to the U.S. Naval Academy in 1913, then served aboard the battleship New Jersey during World War I. He joined the Navy’s Construction Corps in 1918, and studied naval architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After completing his master of science degree in 1921, he spent the next 20 years in the New York, Philadelphia, and Mare Island Navy Yards, as well as at the Bureau of Construction and Repair in Washington, DC.

Wallin’s Salvage Division had three clear goals: Rescue the men who were trapped aboard the ships, assess the damage to each ship, and repair as many as possible. The task was to fix each enough to be able to travel to the larger yards on the West Coast for complete restoration.

The Japanese would come to regret leaving two vital areas of the harbor intact. The first was the fleet’s fuel supply—over 4.5 million gallons. The other was the Navy Yard, whose shops had a vast capacity to fix or build almost anything. “They built liberty boats, 25-foot motor whaleboats, any kind of harbor craft,” recalled Walter Bayer. “They could overhaul a 14- or 16-inch gun. Just pull them around on those big cranes, and handle them like they were toothpicks in those big buildings. They were enormous buildings. They still are.”

Bayer grew up on the Hawaiian island of Kauai. In 1940, he became a civil service employee and went to work in the compressed gases plant in the Navy Yard. He was an assistant supervisor by December 1941. After the attack, demand for his services soared. “When they organized to cut through the bottom of the Oklahoma—she had a double hull—the welders came to us to get acetylene and oxygen for their cutting torches. And they’d use it like water. It would just go in no time.”

The new commandant of the yard was Admiral William Furlong. He and Nimitz were in the same class at Annapolis. Until December 25, 1941, Furlong had been Commander Minecraft, Battle Force. His flagship, the mine layer Oglala, had been sunk off the yard’s main pier, 1010 Dock. Furlong gave Wallin everything he needed: personnel, equipment, and waterfront work space. With a fleet of small vessels roaming the harbor, Wallin could send men and machinery wherever he needed them. He had experts to remove ammunition and ordnance materiel. He had divers trained to operate inside sunken ships. Plus he had the Pacific Bridge Company, whose men were contracted to build Navy facilities across the Pacific.

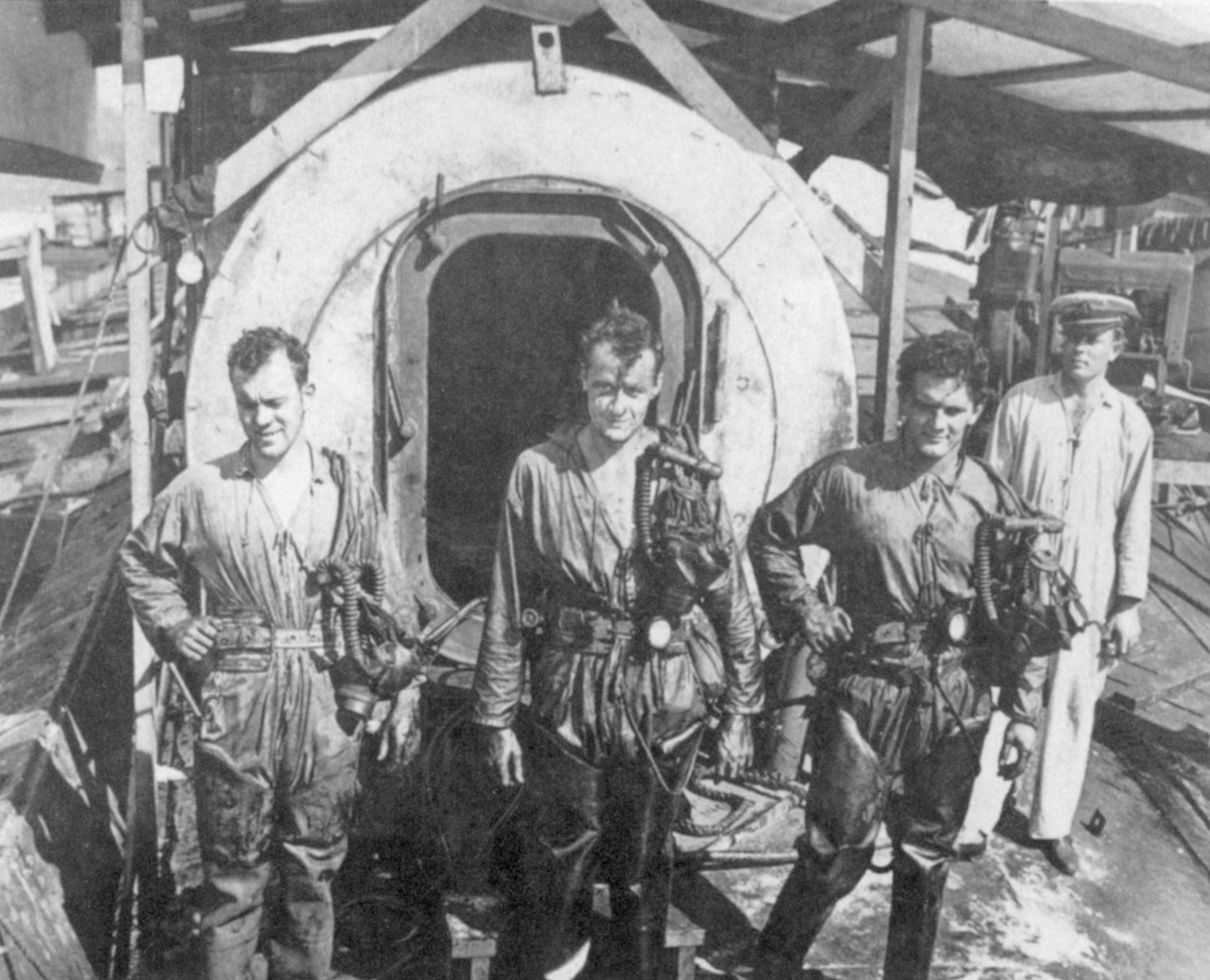

One Navy diver was Metalsmith First Class Edward Raymer. He had joined the service to escape the quiet life in Riverside, Calif. In 1940, he trained at the diving school in San Diego. His work clothes were rubberized coveralls with gloves, a lead-weighted belt (84 pounds), lead-weighted shoes (36 pounds each), and a copper helmet attached to a breastplate. Above water, the suit was awkward. Submerged, the weights counteracted the suit’s buoyancy, permitting the diver to move fairly easily. An air hose ran from the helmet to a compressor monitored by men on the surface. The diver carefully moved the hose with him while working within sunken ships. He often worked in total darkness. He took directions from the surface via telephone cable and needed heightened senses of touch and balance to work with welding torches and suction hoses.

On December 8, 1941, Raymer’s team flew to Pearl. “Welcome to the Salvage Unit,” a tired warrant officer told them. “You will be attached to this command on temporary additional duty, which may not be temporary from the amount of diving work you see before you.”

The team’s first assignment was to determine if men were trapped below the water level in the battleship Nevada. “To accomplish this,” Raymer remembered, “we lowered a diver from the sampan to a depth of 20 feet. Swinging a five-pound hammer, he rapped on the hull three times, then stopped and listened for an answering signal. We took turns for hours. No answering signal was ever heard.” Frustrating as this was, other search parties successfully freed men from the Oklahoma and Utah. The last of them were brought out by December 10.

“Lesser damaged” was the term applied to the condition of the battleships Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Tennessee; the cruisers Honolulu, Helena, and Raleigh; the repair ship Vestal; the seaplane tender Curtiss; and the destroyer Helm.

Pennsylvania was in Dry Dock Number One during the attack, behind the destroyers Downes and Cassin. One bomb hit the battleship, damaging a 5-inch gun and passing through two decks before exploding. The blast wrecked bulkheads, hatches, pipes, and wiring. Her hull and power plant were sound, though. On December 12, she went to the Navy Yard. The damaged gun was replaced with one from the West Virginia, whose decks were awash after she settled into the mud on the bottom of Battleship Row, the victim of several Japanese torpedoes. On December 20, the Pennsylvania sailed for Puget Sound, Wash.

A bomb had struck the pier beside Honolulu. The blast bent in 40 feet of hull on the port side, causing shrapnel damage and flooding. Yard workers began patching the hull, while Honolulu’s crew worked within.

With them was Seaman First Class Stephen Young from Methuen, Mass. Young had just transferred from the Oklahoma. He had endured 25 hours trapped in the battleship. Having survived that, he was impressed by his new job, helping to remove damaged powder cases from the cruiser’s magazine. Shrapnel had punctured many of them, spilling explosive powder on the decks. “Why they never went off, I don’t know,” Young recalled.

Honolulu moved to Dry Dock Number One on December 13. On January 2, she went to the yard for further work. Ten days later, she returned to service.

Helena took a torpedo on her starboard side, flooding an engine room and a boiler room. On December 10, she entered Dry Dock Number Two, which was still under construction. Pacific Bridge personnel borrowed wooden blocks from the yard for the ship to rest upon. After 11 days, she moved to the yard. On January 5, Helena left for the Mare Island Navy Yard in San Francisco.

Maryland was moored inboard of Oklahoma and had escaped torpedoes, but one bomb hit her forecastle. Another struck her port side at water level. No dry dock was available, so repairs were performed at the quays. The yard’s workshops built a wood and metal patch for the rupture in the hull. A barge-mounted crane lowered the patch into the water, and divers fitted it in place. The water was pumped away, and repairs continued inside the ship. On December 20, she left for Puget Sound. Her final repairs were completed there on February 26, 1942.

Tennessee was inboard of West Virginia. Multiple torpedo hits had sunk the outer ship, trapping Tennessee against the concrete mooring quays. A direct hit to the battleship Arizona’s magazines had sunk that vessel and thrown burning debris on the Tennessee’s decks. Arizona’s burning oil spread across the water, engulfing Tennessee’s stern. Crewmen fought with hoses to keep the fires away. Her forward magazines were flooded to keep them from exploding. The ship’s propellers were turned at speeds up to 10 knots in an effort to keep flaming oil away. The crew was forced to abandon her.

Men from the yard and the repair ship Medusa welded Tennessee’s heat-warped stern plates. A total of 650,000 gallons of oil was pumped from the ship. Divers placed explosive charges on the quays. These were detonated on December 16, finally freeing Tennessee from her trap. She spent two months at Puget Sound and eventually returned to duty on February 29, 1942.

Outboard of Arizona was Vestal. Two bombs found her, falling from a thousand feet or higher, smashing straight through her, and exploding underwater. The flooding made her list to port and settle heavily at the stern. To escape the burning Arizona, the Vestal’s captain backed his ship away. Vestal was 33 years old, and her watertight integrity was not enough to keep her afloat. Two tugboats guided her east to shallow water, beaching her at Aiea Shoal.

Being a repair ship, Vestal had the resources for crew to begin mending her, but she had to wait her turn for dry-docking. It came two months later. Vestal returned to duty on February 18.

A torpedo flooded Raleigh’s engine room. A bomb ripped through three decks and out her side. It exploded uncomfortably close to a compartment storing aviation fuel. When the cruiser’s captain ordered counterflooding to balance the ship, several doors failed. The tugboat Sunnadin and a barge were tied to her port side to save her from sinking.

Men from repair vessels helped the crew rebuild the decks and transfer fuel and water from the Raleigh. She went into Dry Dock Number One on January 3. Running on one engine, she sailed for Mare Island on February 14. After receiving a new engine and electrical parts, she returned to duty on July 23.

Curtiss had no armor and suffered for it. One bomb hit. Three missed, but not by enough. A damaged Japanese plane struck her starboard crane and exploded. Smoke from burning cork insulation made it more difficult for the crew to fight the fires.

Dry-docked from December 19 to 27, Curtiss had to vacate early, making way for higher priority jobs. She could not return until April 26, and was substantially repaired by May 28.

Helm had escaped the harbor, but while searching for submarines she was bracketed by two bombs. The shock caused flooding forward and tripped circuit breakers. With the dry docks full, Helm went to the yard’s marine railway on January 15. There she was hauled out of the water for welding and patching. At the end of the month, she left for San Diego.

Each accomplishment brought another part of the Pacific Fleet to life. But these successes were modest compared to what lay ahead. Six battleships, one cruiser, three destroyers, and a mine-laying ship had received severe attention from the Japanese.

Destroyers were desperately needed to protect Allied merchant shipping from enemy submarines. Commander John Alden, himself a submariner, wrote, “In addition to the mere urgency of obtaining ASW [antisubmarine warfare] vessels, other factors added weight to the balance. One was the fact that of all the material needed to build new destroyers, most critical and hard to obtain were main propulsion plants. In the effort to break the bottleneck, DE’s [destroyer escorts] and frigates were designed around every conceivable type of power plant … but there was no substitute for the steam turbine in destroyers.”

In addition to the catastrophic loss of the Arizona, one of the most spectacular of the December 7 victims was the destroyer Shaw. She had been on blocks in Floating Dry Dock Number Two. Three bombs struck the ship, rupturing fuel tanks. Fire swept through the ship to her magazines. A tremendous blast wrecked her entire forward section. Twenty-five men died, and 15 more were injured. Five bombs hit the dry dock. To protect it, workers submerged the dock, and the tugboat Sotoyomo sank with it.

To casual observers, Shaw seemed a total loss. Her bridge was destroyed, and her bow was literally gone. But her engineering machinery was intact. She was towed to the marine railway on December 19. Hull repair experts took measurements and set to building a temporary bow.

Navy divers sealed over 150 holes in the hull of the dock. It was raised on January 9, and ready for service on January 25. Six months later, so was Sotoyomo. Shaw was the first ship back into the dry dock. The next day, her new bow was attached along with a new mast and a temporary bridge. This made her look more like an overgrown PT boat than a destroyer, but it worked. On February 4, Shaw left the harbor for power trials. Five days later, with cheers shouted from all over Pearl, she left for Mare Island. A permanent bow awaited her there. Of the badly wounded ships, Shaw was the first to return to sea.

The destroyers Helm and Henley escorted Shaw eastward. Seaman First Class Arthur Schreier from Watertown, Conn., was on Henley’s No. 4 gun mount. He spent many hours watching Shaw plow through the waves. “I felt so sorry for those guys,” Schreier recalled, “because without a bow, you know—they had this little stubby thing welded on. Boom. Boom. Boom. Every wave, for six days.”

Fireman First Class Alfred Bulpitt from Centerdale, RI, was aboard the Shaw. Manning the port engine throttle, he knew she was traveling at only a third of her top speed. “It took us quite a while. We only had one fire room and one screw working. And we had a reduced crew. But I don’t remember anyone saying we wouldn’t make it.”

They did make it, arriving at Mare Island on February 15. Waiting for Shaw was another dry dock and her new bow. She was ready by July, returning to duty as an escort for convoys to Pearl. By the fall, she headed west to join the fight for Guadalcanal.

Destroyers Downes and Cassin had similar troubles. “They had gone through every kind of ordeal which ships could be subjected to,” Wallin wrote. “From bomb hits to severe fires, to explosions, to fragmentation damage, etc. These vessels were the only ones of the Pearl Harbor group that suffered all the kinds of damage enumerated.”

A bomb had ripped through Cassin to explode on the floor of Dry Dock Number One. Two more hit the dock, one on each side of the ships. A fourth blasted Cassin again. A fifth destroyed Downes’ bridge. Fragments punctured fuel tanks on both ships. Fire spread through the dock, detonating fuel and ammunition on Downes. Part of a torpedo landed 75 feet away.

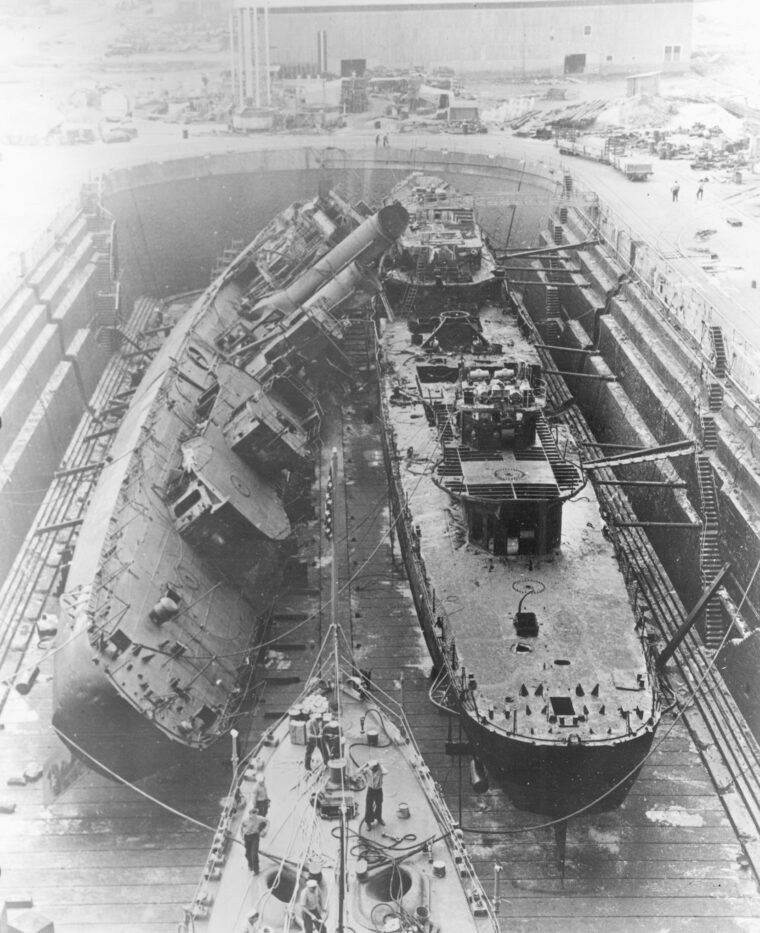

Without power or water, no one could fight the fires, which now threatened the neighboring Pennsylvania. Her captain ordered the dock flooded, but as the water rose, so did the flames. Cassin came afloat at her stern and finally collapsed onto Downes.

Both destroyers remained in the dock for two months. Other ships came in for repairs. Each flooding and draining made the destroyers sway and roll, hurting them more. On February 5, Cassin was carefully reset on her blocks. The next day, Downes was towed to the Navy Yard. Cassin followed 20 days later.

The destroyers’ hulls were ruined, but their propulsion machinery was sound. Nimitz, the Bureau of Ships, and the Chief of Naval Operations debated the question: repair them or scrap them? On May 7, the Bureau of Ships found the solution. “Recommend new hulls be built at Mare Island. The Bureau considers that sufficient of the original Cassin and Downes material can be worked into the [new] hulls to thoroughly justify the retention of the original names for the new ships.”

Through the spring and summer, nearly 1,000 tons of useful equipment was removed, carefully catalogued, and shipped to Mare Island. By August, what remained of Downes was scrapped. The Cassin followed suit by October, but the hearts of both vessels, including the 37-ton stern sections bearing their names, were saved. On May 20, 1943, Downes was “relaunched.” So was Cassin on June 21. There was no precedent for this in Navy history. Never had a ship been launched twice. “In both cases there was a minimum of fanfare,” Alden wrote. “Like a quiet ceremony with discreet minimized publicity for a bride being led to the altar for the second time.”

Of the battleships, only Nevada had been able to run for the sea. However, she took hits from a torpedo and at least seven bombs. One smashed her forecastle, blowing a 25-foot triangular hole on the port side. Another crashed through the ship—including a gasoline tank without igniting it—and detonated beneath her. Flooding was too heavy to be stopped.

Watching from Oglala, Admiral Furlong ordered two tugboats to move Nevada to the shallows at Waipio Point above the harbor entrance, where she was beached. Her bow settled until the deck was nearly awash.

Admiral Nimitz’s inspection of Nevada was a grim one. The ship had been wrecked by blasts and fire and fouled with oil and polluted water, but her men were determined to win. Nimitz consented.

Using measurements from Nevada’s sister ship, Oklahoma, yard shipwrights built a patch to cover the holes. It was a huge piece of craftsmanship, 55 feet long, 32 feet deep, and curved to fit the ship’s bilge.

The divers had a frustrating time securing the patch. The explosions had warped the hull, and it was impossible to seal the patch completely. It had to be discarded. The alternative was to gamble on the strength of Nevada’s bulkheads. Divers tightened every door and hatch in the ruptured compartments and bolted patches over smaller holes in the hull.

Removing water from the ship was a headache, too, given the number and types of pumps available. The strongest could pump 4,000 gallons a minute, but there were not enough of them. Some could draw water up about 15 feet, but no higher. To compensate, engineers arranged them so that the smaller ones brought water to areas where the stronger pumps could move the water up and out of the ship. This was done with care. If one section drained much faster than others, Nevada could list or capsize. Although the pumps gradually moved water out faster than it came in, the ship remained in danger until dry-docked.

The drying compartments sobered the most hardened men. The filth was appalling. A mixture of oil, mud, paper, clothes, and rotting food filled every part of the ship. And there were the bodies of men who had died in the attack. They were taken to the naval hospital for identification and burial. Then work parties brought in hoses and sprayed every object and surface with sea water, followed with Tectyl, a cleaning chemical that absorbed water from anything it touched.

To increase buoyancy, Nevada’s crew transferred the remaining stored oil from the ship. Wreckage was cleaned away. Guns, ammunition, electric motors, and auxiliary equipment were brought out. Much of it was salvable, despite being submerged for nearly three months.

The optimism of the salvage crew was tempered by the discovery of hydrogen sulfide, an odorless toxic gas created when oil and polluted sea water are mixed under pressure. On February 7, one man opened a gas-filled compartment and collapsed from a fatal dose. While trying to rescue him, five more sailors were also overcome. Only four recovered. Increased ventilation became top priority. No man was permitted on the ship without a gas mask and a litmus paper badge to indicate if the gas was present.

One week later, Nevada was afloat. A last inspection was made of every bulkhead and hatch. Any serious leak would send the battered battleship to the bottom. On February 14, two tugs brought the Nevada to Dry Dock Number Two. Nimitz and Furlong were with the cheering crowd that welcomed her. On April 22, 1942, she left Pearl Harbor for Puget Sound Navy Yard for final repairs and modernization.

California posed greater problems. She had been hit by two torpedoes and one bomb and jarred by several near misses. Arizona’s burning oil had forced California’s crew to abandon her. She took three days to sink to the bottom, settling with a list to port. Her main deck was 17 feet beneath the surface.

The Yard Design Section feared that patching and pumping out the ship would fail. As she regained buoyancy, the weight of the water above her decks might collapse them. One option was to build a cofferdam around the ship. A barrier of pilings driven into the harbor bottom would permit men to drain the water within and effect repairs. It was a good plan, but expensive and complicated.

An alternative was found: build two cofferdams attached to the ship to enclose her forecastle and quarterdeck. Barge cranes lowered huge wooden planks along the ship’s sides. Pacific Bridge divers bolted them to the hull and sealed them with lengths of hose filled with sawdust and oakum (hemp mixed with tar). The planks were 30 feet high and varied in width and thickness. They were weighted down with sandbags and reinforced to endure external water pressure as the interior was pumped out.

The divers plugged more holes. One needed a 15-by-15-foot patch. As with Nevada, the pumps eventually caught up to the leaks, then passed them. Oil was skimmed from the surface and transferred from the bunkers to a barge alongside. Eventually, over 200,000 gallons were recovered.

By the end of March, California had risen to a nearly even keel, but on April 5 an explosion blew out the hull patch. She began settling at the bow. Gasoline vapors had leaked from a fuel tank and ignited. The patch was ruined, and there was no time to build another. Another battleship was coming in for repairs, and California had to meet the tight schedule for dry dock time. Raymer’s team contained the flooding on the ship’s third deck. The men took turns welding a warped hatch shut. After 12 hours, it was secured and the flooding stopped. Four days later, California entered Dry Dock Number Two. She was on time.

California’s electric drive engines had suffered heavily from the saltwater. The job of rewrapping miles of wire called for specialists not available at Pearl. A team of engineers flew in from the General Electric Company in Schenectady, NY. Through the summer they concentrated their efforts on one alternator and two motors—just enough to get the ship to Puget Sound. They finished in the autumn. California headed for Puget Sound on October 10, 1942.

West Virginia’s problems were even worse. Two bombs and at least seven torpedoes sank her, killing over a hundred men. She, too, had electric drive. Her steering system was ruined, and her rudder was blown off. Over 200 feet of her port hull was wrecked. Raymer wrote, “Raising West Virginia would be far more difficult than either the Nevada or the California had been. It would test the ingenuity and salvage expertise of every faction involved in the operation.”

Yard craftsmen came through again, building 14 hull patches in sections 13 feet long and over 50 feet wide. Curved at the bottom to fit the ship’s bilge, they straightened to climb the sides to high above the surface. Like the walls of a fortress, each was made of metal beams and 12-by-14-inch timbers, with four-inch planking beneath. Several had access doors so divers could enter the hull. To counteract its buoyancy, each was weighted with lead. After each section was fitted in place, the lead was removed. Divers filled the seams with 650 tons of underwater concrete. Since this added more weight than the hull could endure after dry-docking, the divers finished by welding steel reinforcing rods to the hull.

After the patches were secured, the pumps lowered the water within by a few feet, but no more. “No further headway was made in dewatering,” Raymer recalled. “Most of the leakage was found to occur in the areas contiguous to the patches from leaking seams, shrapnel holes, and loose rivets.” Every hole mattered. Raymer’s men sealed all they could find with smaller patches or wooden plugs.

Salvage crews moved deeper into the ship, mindful of the hydrogen sulfide threat. A medical officer worked with them, maintaining a bulletin board showing which compartments were safe. They brought out more oil, ammunition, and machinery along with the bodies of 66 men who had died in December.

The bodies of three sailors were found in a dry storeroom. With them was a calendar. The days from December 7 to December 23 were crossed off. The men had food and drinking water, but their oxygen had run out. “The discovery of these three men in an unflooded compartment caused a profound sense of anguish among our divers,” Raymer said. “Especially shaken were Moon and Tony, who had sounded the West Virginia’s hull on December 12 and reported no response from within the ship.” The men had been in the starboard side, hard against Tennessee’s port side. It had been impossible for divers to reach that area.

Recalling his part in the salvage, Electrician’s Mate Second Class Claude Miller wrote, “This consisted mainly of endless days of chipping the years of paint coats from the bulkheads. This paint was in many places a full one inch thick or more, and shattered like cement when chiseled by air-driven chipping hammers.” A native of Trenton, Mo., Miller had traveled far with the Navy, with no shortage of work. He had been with the aircraft carrier Yorktown at the Battles of Coral Sea and Midway. After his carrier was sunk, he and many of his friends were reassigned to Pearl to assist with the recovery work there.

“We worked in very hot and sometimes toxic spaces in half-hour shifts,” he added. “Then we would go up to topside for about half an hour, for fresh air and pineapple juice. Later on I was assigned to clean, rewind, and restore small electric motors, and also manage the engineers’ tool room.”

On May 17, West Virginia rose from the bottom. Work continued over the next three weeks to reduce her draft. Finally, it was down to the required minimum, 33 feet. She just fit into Dry Dock Number One on June 9. She went to the yard a few days later and stayed for 11 months. In April 1943, as Miller put it, “The old warrior finally was made ready to move on her own, and we sailed to Bremerton Navy Yard for the balance of the restoration.”

Oglala came last. On December 7, a torpedo had passed beneath her to strike the inboard Helena. Since the ships were tied together, the explosion ruptured Oglala’s bilge. Two hours later she capsized to port. Only her starboard side amidships remained above water. This led to the cynical joke that when she saw Helena get hit, Oglala died of fright.

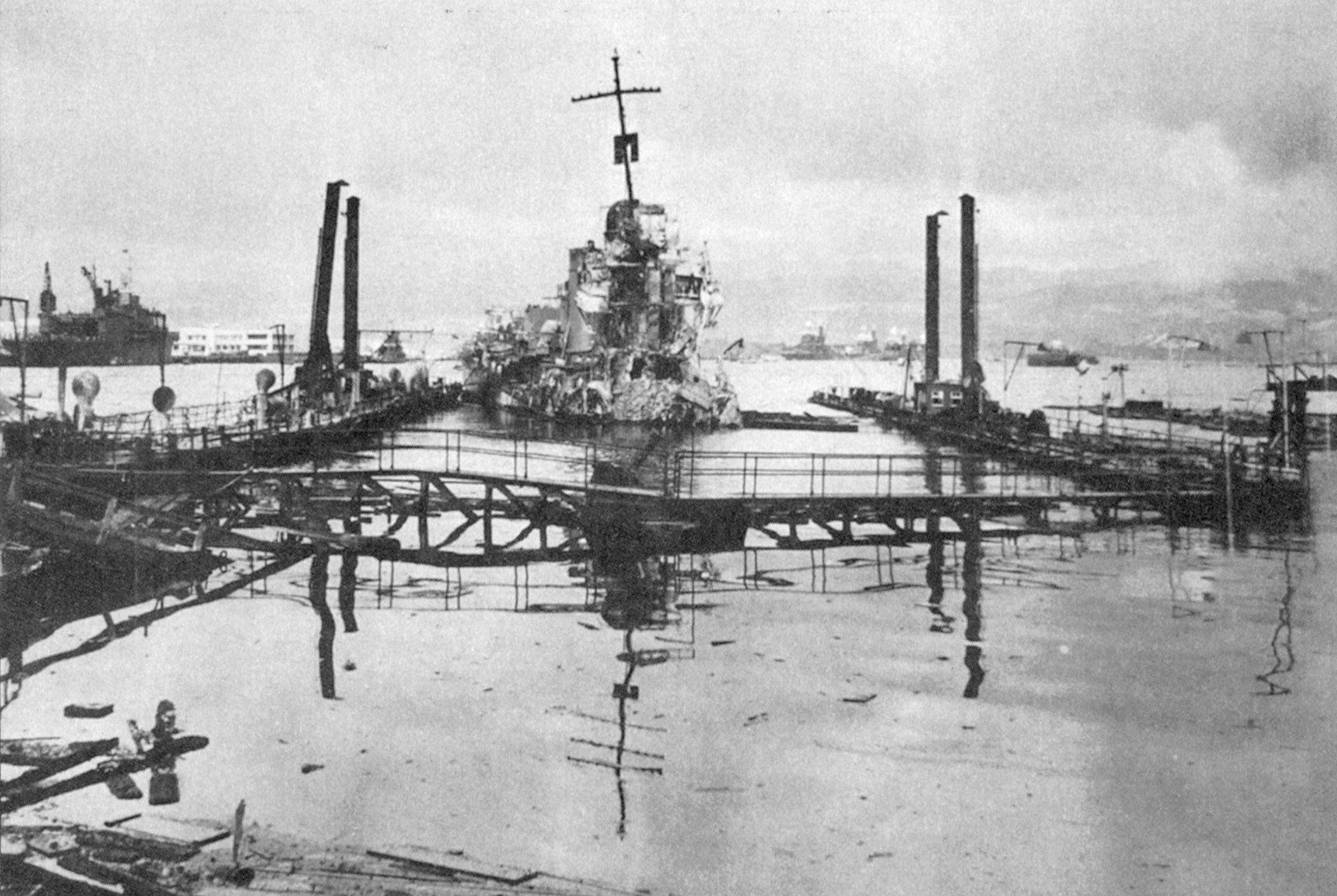

Originally a coastal steamer, Oglala had joined the Navy in World War I. She was 34 years old, and her compartments were not designed to endure battle damage. The merits of raising her seemed thin. She was blocking valuable pier space, and scrapping seemed the best option. However, since demolition experts and equipment were unavailable, men from the yard and the repair ship Ortolan set out to rescue her, employing three elements.

The first was a set of 10 submarine salvage pontoons. Each was a giant metal cylinder that could be flooded and sunk, then attached to massive chains placed under the hull by divers. When pumped out, each pontoon would exert nearly 100 tons of lifting power. Second was a barge with winches to haul cables attached to Oglala. The third was compressed air, pumped into the hull to displace some of the water within. This required extreme care, given the hull’s weakened condition.

On April 11, bridles linking the chains to the pontoons broke. The pontoons floated free. They were resunk and new bridles were attached. Another attempt was made on April 23. Oglala rolled up to rest on her bottom with a 20-degree port list. Further work reduced this to 7 degrees, but her bow remained 6 feet below the surface and the stern was 19 feet deeper.

Cofferdamming came next, using wood and steel from the California salvage. Divers secured the sections and patched the port bilge, where the worst shock damage was. They cut free the wooden deck house, and a barge crane hoisted it away.

The cofferdam was completed in June, and pumping began. After the water had dropped seven feet, a section of the dam failed. Captain Wallin dryly noted, “This was not a design failure, but resulted from the action of some ‘practical men.’” The men in question had substituted 12-inch-square timbers for the steel H-beams specified in the designs. The wood was replaced with steel. Pumping above and from within the ship resumed. On June 23, Oglala floated.

On the night of June 25, several pumps became fouled with debris, and Oglala’s bow sank. Her stern followed. The pumps were cleared, and the vessel was refloated once more on June 27. She sank a third time on June 29 when the cofferdam failed again. By then Oglala had earned the nickname “the Jonah ship.” She was returned to the surface again by July 1.

Fire broke out aboard Oglala that night when a technician spilled gasoline on a pump’s exhaust manifold. He then dropped the burning gas can into the water, igniting the oil on the water’s surface. It took 20 minutes for men from Ortolan and the Navy Yard Fire Department to extinguish the blaze. To their weary relief, the salvage men found that damage to the cofferdam was superficial.

On July 3, Oglala entered Dry Dock Number Two. To Wallin, the ship looked like Noah’s Ark without a roof. Despite her troubles, her hull was in better shape than expected. She eventually returned to service as a repair ship, aiding many other vessels throughout the war.

The remaining victims of December 7 were beyond saving. Arizona had suffered several bomb hits. She had sunk with the loss of more than 1,100 men. One bomb hit had detonated her forward magazines and broken her back. Her armament and fuel were taken ashore, and Arizona was left where she sank. More than 20 years passed before the famed memorial was built above her.

Many torpedoes had struck Oklahoma. “I can vouch for five,” Young recalled. The blasts disintegrated much of her port hull. Fifteen minutes after the attack began, she capsized. She stayed that way for nearly six months. When men and resources were finally available, the most spectacular chapter of the Fleet salvage began.

The man responsible for leading the staggering effort to raise the Oklahoma was Commander F.H. Whitaker. Born and raised in Tyler, Tex., Whitaker was a naval construction expert who, like Wallin, had graduated from Annapolis and M.I.T. Whitaker and his staff spent months running tests to determine the most effective method to raise the ship. Experiments with a 1/96 scale model of the battleship in Pacific Bridge’s laboratory in San Francisco demonstrated that the Oklahoma could be gradually rolled into an upright position.

Divers placed pontoons at key points where the superstructure was buried in the mud. They also tested the strength of the mud. It had to be hard enough, or the ship might drag along the bottom as the winches turned. Fortunately, it was. The divers placed an additional 4,500 cubic yards of coral soil along the inshore side of the ship’s bow. Twenty-one concrete foundations were poured near the water’s edge on Ford Island. Seated in them were electric winches. With a system of hauling blocks and pulleys, the winches’ combined strength could exert a titanic 345,000 tons of pulling force. Forty-two miles of one-inch wire ran from the winches, through the blocks, out over a row of 40-foot A-frame towers built on Oklahoma’s hull, and finally to pads welded to the ship.

It looked like something from Gulliver’s Travels, but the objective was to free a giant, not restrain it. The righting began on March 8, 1943. “With a lurch and a groan the Oklahoma started her slow but steady rotation,” Raymer wrote. “Everyone was jubilant. They cheered lustily a noted. “We were there at the beginning, and we were there at the end.”

Vestal repaired ships in the Solomons. This was incalculably important. By contributing to the repair of other vessels when the future of the Pacific War was still in doubt, she paid many times over for the effort to save her at Pearl.

Nevada, Tennessee, and Raleigh joined the Aleutian Islands operation of 1943, reclaiming Attu and Kiska from the Japanese. Nevada went east to join the Atlantic Fleet, supporting the invasions of Normandy in June 1944, and then southern France in August.

Tennessee joined West Virginia, California, Maryland, and Pennsylvania to participate in the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944. The Japanese had summoned the majority of their dwindling naval forces to attempt to disrupt the American landings at Leyte in the Philippines. It was the largest naval campaign in history and marked the end of the Japanese Navy as an effective fighting force.

In a series of torpedo attacks, American destroyers ambushed a Japanese battleship force on the evening of October 25 at Surigao Strait. Using their new fire-control radar, Tennessee, West Virginia, and California followed up, firing more than 220 rounds from their main batteries. Maryland’s older radar system could track where the rounds fell, and with that she added 48 shots of her own.

By dawn, two Japanese battleships, Fuso and Yamashiro, had been sunk, along with three destroyers. The badly damaged cruiser Mogami was finished off by American torpedo planes. Surigao Strait was the last surface action fought between opposing battleships. Having waited almost three years for it, the veterans of Pearl Harbor savored the victory to the fullest. “It was a matter of great satisfaction to many Americans,” Wallin wrote. “And it must have been a bitter pill for the Japanese.”

Helena fought in the battles of Cape Esperance and Guadalcanal. During a night action, she fought off Japanese warships that were shelling Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. On September 15, 1942, she rescued survivors when the aircraft carrier Wasp was sunk, but her luck did not last. Helena was torpedoed during the Battle of Kula Gulf on July 6, 1943. She broke apart and sank. Approximately 170 men died with her.

The other ships served to the end of the war. Following the Japanese surrender, California, West Virginia, and Tennessee remained on station in Japan. But by the autumn of 1945, the U.S. Navy was the largest in the world, and the most expensive. Peace meant shrinking military budgets. All but one of the ships that rose from ruin at Pearl Harbor were decommissioned and consigned for scrapping by 1947. Only Curtiss endured. She served in the Korean War. As a science vessel, she took part in nuclear weapons tests in the Central Pacific and research work off Antarctica. She was decommissioned in 1957 and finally broken up in 1972.

It all seemed heartless, and still does, to the men who lived and fought on these ships. Still, financial considerations aside, the ships were old. Despite their upgrading, it was becoming difficult for them to keep pace with newer ships coming into service, let alone those on the drawing boards. They had done their work.

Over 30 years after the Pearl Harbor attack, Ed Raymer retired from the Navy. Looking back, he readily acknowledged that he was part of a tremendous accomplishment. In 1996, Commander Raymer wrote, “Navy divers and Pacific Bridge civilian divers formed one leg of a salvage triad; salvage engineers and the Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard comprised the other two. One leg needed the assistance and support of the other two to be effective.”

Vice Admiral Homer Wallin retired in 1955, finishing a career spanning 40 years. He had left Hawaii in July 1942 for a new assignment. During an awards ceremony on the deck of the aircraft carrier Enterprise, Admiral Nimitz presented Wallin with the Distinguished Service Medal. As Wallin wrote, “Admiral Nimitz read the citation for the work performed by the Salvage Organization and ended by adding, ‘for being an undying optimist.’ The Medal was accepted by me in the name of the organization which I had the honor to head.”

Wallin meant it. He knew the value of every man who helped him. “Enough cannot be said in praise of the salvage crew,” he asserted. “They worked hard and earnestly. They soon saw that the results of their efforts exceeded the fondest hopes of their supporters and they were urged on by their successful achievements.”

Without question, the Pearl Harbor salvage operation was the largest in naval history. The men behind it lived up to their creed: “We keep them fit to fight.”

Mike McLaughlin lives with his wife Geralyn, a Boston public school teacher, in Winthrop, Massachusetts. He interviewed several New England men who participated in the Pearl Harbor salvage effort. He was assisted by the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association and Pearl Harbor Historical Associates. In addition to WWII History, Mike also writes for American Veteran, American Heritage, and Maxim.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments