By Robert Schultz with James Shell

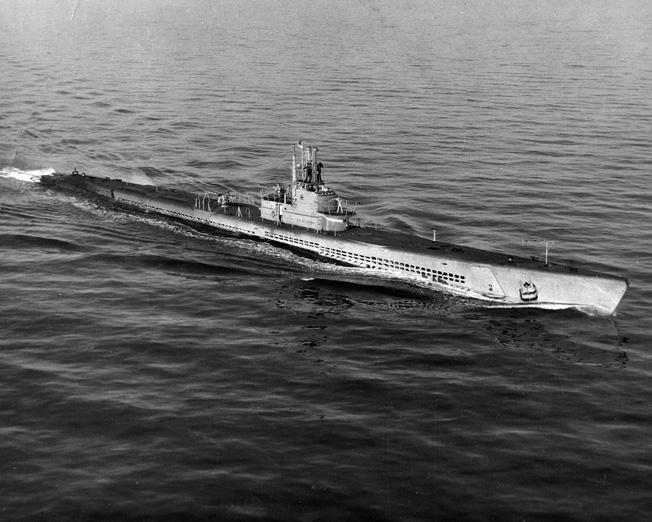

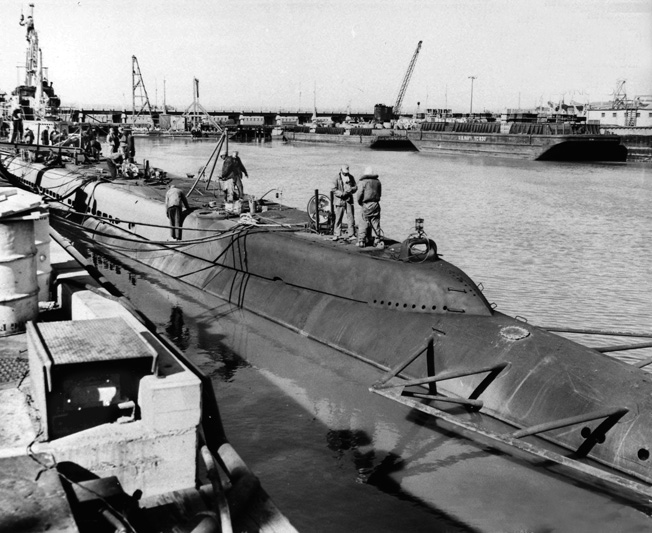

By Christmas 1941, Robert Hunt, torpedoman on the submarine USS Tambor, had witnessed the Japanese bombing of Wake Island, had slept in the Tambor’s forward torpedo room on the way back to Pearl with a bomb-induced leak bubbling in the corner, and had stood on his sub’s bow and seen the devastation of Battleship Row as debris in the oil-slicked harbor bumped against the hull.

“I Knew the Odds”

Five days later he wrote a letter to his brother Dick, who was stationed at the Naval Air Station in Corpus Christi, Texas. Hunt mailed the letter from San Francisco, where the Tambor had been sent for repairs before its war-long service throughout the Pacific. In it he mentioned Dick’s performance in a play, girlfriends, and, with sadness, the death of sister Marge’s newborn child. The letter was filled with bravado and euphemism (and colorful spelling), and for later generations it evokes the American 1940s as surely as a Benny Goodman swing tune or a Bob Hope road movie. But its purpose is clear. The letter, typed and signed with Hunt’s full name, is a last will and testament.

Dec. 30 [1941]

Dear Dick—

I received your last letter o.k. and it was about time you wrote. Bet you made quite a leading man in that play—maybe the movies will put in a bit for you when you get out. Guess they could use a few men in the picture business eh’. Can’t tell you much because of the naval censors—guess it’s a good idea. We all get the news out of the papers anyway.

My little red head went back last month so think I’ll have to get busy again and find another. Sure hated to see her go as we really had a good one planned for the holidays.

The baby was a boy as you probably know and only lived a couple of weeks. Marg sure can take it as I received a letter from her shortly after and she seemed all-right. I sure wanted that kid to live and be a boy for her sake, but guess that’s the way it goes. Maybe she’ll have another and we can be uncles anyway. See that you don’t knock out any down there—maybe you’d have to marry the gal, she may be a queen, but that family of hers maybe don’t want any of those war babies. From the way you talk you must have several standbys for when you get hard up—not bad if they stack up as nice as you say and I imagine they do.

By the way—if I should get a heart attack and kroke one of these days I want you to get half my dust. Marg gets the other half. I didn’t tell Marg so don’t mention it to her, but Dad knows about it. Take half my insurance and my savings account is in the bank at home—Dad has a record of it in his safety deposit box. I guess if you get nocked off you have six months pay coming too so get that for you and Marg too. You can do what you want with it—get married—raise hell—or just throw it away. If gram is still living see that she gets something, but you take care of it yourself. All this is just in case my heart goes bad or if I stub my toe and get poisoned or something—maybe my red head will shoot me when she sees me again. I’ll sign this letter and you save it in case you’d have trouble collecting. I figure if Dad had any more money he really wouldn’t need … anyway you guys is me pals.

Don’t expect too many letters as all I can say in a letter isn’t very interesting. Give em hell Dick—and pick off a few of those little guys for me. I think I received your last letter—written about a month ago. I’ll write more later.

Your bro—

Robert Russell Hunt

Beneath the swagger and self-deprecation, the letter reflects Bob’s state of mind after his first wartime patrol. “I didn’t figure I was going to make it,” Bob told me. We were speaking on the phone one afternoon in 2006. I was in Virginia and he was in Iowa, resting in his apartment after cataract surgery that morning. “I was a poker player,” he said. “I knew the odds.”

A Statistical Anomaly

By mid-war, as submariners heard of lost subs and the deaths of buddies on other boats, the common wisdom said that after four patrols you were pushing your luck. The common wisdom was not far off. Twenty-two percent of submariners who went to war died, the highest rate of any service. Eventually it became standard practice to transfer to a land-based support crew after your fourth patrol, then later, perhaps, go out with a different boat that needed your specialty. So Bob Hunt’s 12 straight patrols on a single boat are rare, if not unmatched.

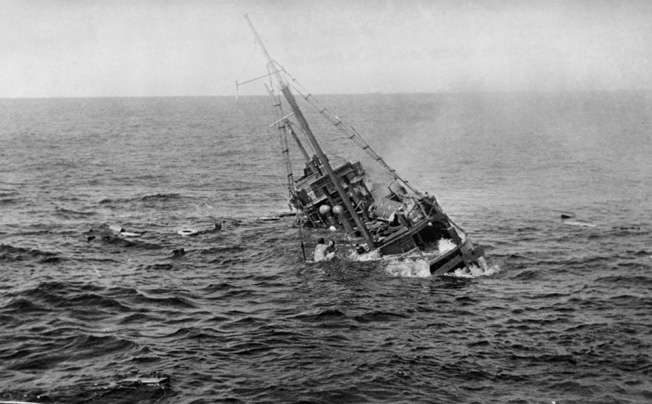

His survival, a statistical anomaly, was often in jeopardy. During the Battle of Midway he was on night watch at the port lookout when the Tambor signaled an unidentified convoy, received an incomprehensible reply, and dove. The two Japanese cruisers that had spotted the sub took evasive action, collided, and were both damaged. The next day the Mikuma, trailing oil, was sunk by American planes, and the Mogami was ravaged. One of the most famous photographs of the Battle of Midway shows the Mikuma smoking under the wing of a circling Douglas SBD Dauntless dive-bomber. On the Tambor’s eighth patrol Bob was in the forward torpedo room when they sank a freighter off the coast of China, then had to apply right full rudder to dodge one of their own torpedoes that had run in a circle and come back at them. Then it came around a second time and they dodged it again. About the incident he wrote in his diary: “It wasn’t half an hour ago so am still a little shaky—first time really scared.”

On the boat’s tenth mission the Tambor made a night surface attack on a Japanese convoy, was silhouetted by a burning tanker it had torpedoed, and was almost rammed by a Japanese patrol boat. Lookouts, without the aid of binoculars, saw Japanese sailors running to their deck guns, but a crew member saved the sub with extremely accurate 20mm fire along the length of the patrol boat’s deck. The boat missed the Tambor by a mere 20 yards, close enough for the captain to read the numbers on the Japanese hull by the light of the machine gun’s tracers.

Days later, after the Tambor sank another freighter and tanker, Bob and the crew sat on the bottom at 270 feet and time and again listened to the screws of a destroyer passing over, emptying its racks of depth charges. Even sitting on the bottom, the Tambor sagged and hogged, shaken by close explosions. Throughout the boat, crew members worked to stop leaks and keep vital equipment running. As the attack wore on, a lack of oxygen made for laborious breathing. And when the Tambor finally tried to make a run for it, the boat was mired in sludge and sand stirred up by the explosions. More hours of shifting ballast, blowing tanks, and reversing props drained the sub’s batteries to dangerously low levels before the boat finally broke free.

After 17 hours submerged, severe damage included the destruction of its radio antennae, so all communications were cut off until temporary repairs could be made. Only when they returned to port did the crew learn that Tokyo Rose had reported the Tambor destroyed with all hands.

“I wasn’t not going to do it.”

Luck, certainly, was involved in Hunt’s survival. But physical survival is one thing, mental endurance another, and Bob knew many crewmates who went quiet near the end of a patrol, then were never seen again. What in his makeup allowed him to persist? And why, in an all-volunteer service, did Bob go out again and again, his home from December 1940 to September 1944 a bunk in the forward room between reload torpedoes?

Bob met this final question with a practiced series of evasions, but one day I pressed him. We sat in his small bedroom-study with photos of the Tambor, crewmates, friends, and his Great Lakes training class hanging on the walls. A single bed was tucked into a nook in the wall across from our two chairs and a desk with a computer. The room was smaller than most compartments on Bob’s sub, and we sat almost knee to knee. In similar spaces men endured patrols of 60 days or more. I wanted to understand what motivated Bob to keep going out. At first he made jokes.

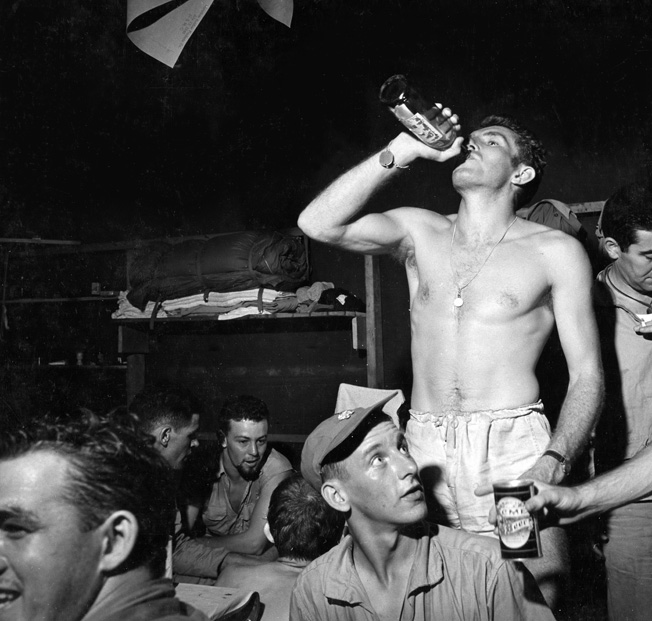

“After a mission we’d come in and had two weeks off. We might get hammered for two or three days, but we always knew when we were going to leave. We were partying so much the night before we went, the first thing I know is I’m on the boat and I feel a swell. We’re going out on war patrol, and I said, ‘Shoot, I’ve done it again!’” He laughed and I laughed with him. I asked again.

“Well, you got pay-and-a-half and nobody bothered you. It wasn’t regular Navy. We didn’t pay a lot of attention to the officers. Besides the captain and the navigator, they were mostly a box of rocks.” We laughed again.

He paused, and we let the quiet settle in the tiny room. “They were killing my buddies like crazy,” Bob said. “I was mad as hell at them. I wanted to get out there and fight back.”

“So it was very personal,” I said.

“Yes,” Bob agreed. “Guys I worked with— guys who were my friends—would transfer to another boat and get killed.” Then he thought some more. Finally, he arrived at what I took to be his bottom line.

“When it came time to go,” he said. “I wasn’t not going to do it.”

The double negative expressed the obdurate point of decision, and Bob experienced it as a recurring challenge. Had he reached the point where he could step off the boat and not go out to the fight? The answer was never yes. Only once was he almost persuaded to stay behind. His hands had been shaking for a long time, but now it had gotten so bad he had to grip a cup of coffee tightly with both to keep from spilling. Then his friends, Ole John Clausen and Harry Behrens, before a morning departure, took him to the base hospital to get a medical leave. Bob told the Navy doctor his hands wouldn’t stop shaking. The physician ordered a urine test that came back “90 proof.” The three men had been drinking hard since the night before.

Then the doctor told Bob to stretch out his arms and lean with his hands pressed against the wall. When Bob did, he said, “See, your hands aren’t shaking now.” Bob reported to the boat, served on his 11th patrol, then one more after that. He finally left the boat before its 13th and final patrol and was sent to Hunters Point, San Francisco, where he organized and taught a torpedo tube school.

Living Hard

Alcohol was an important way that Bob cut loose during two-week liberties between patrols that routinely lasted two months. Something needed to be obliterated. Brooding was dangerous, and members of the “silent service” were forbidden to talk about their missions to those outside the club. Well-lubricated parties in Hawaii or western Australia amounted often to group purges that ancient devotees to Dionysus, god of wine and self-abandon, would have understood perfectly. Drinking on patrols was limited to the occasional shot of brandy doled out to the crew from the pharmacist’s cabinet after a successful attack or a severe depth-charging. But in Bob’s forward torpedo room a hand-made still sat in the bilges and transformed unneeded torpedo fuel stored in two 50-gallon barrels into drinkable alcohol. The fuel was called Pink Lady because of the oil that tinted it and made you sick if you didn’t remove it with the still fashioned by mechanics out of copper tubing, tin cans, and a hot plate. During leaves the still was transferred to a hotel room in a crewmate’s sea bag and kept running in a bathtub.

In my conversations with him, Bob was equally candid about the war patrols and the liberties. He recounted the alternation of confinement and release, of deprivations and desperate compensations. When these men in their teens and early twenties returned to base, they popped ashore like corks out of champagne bottles. Pale and haggard, often plagued by prickly rashes because of the Tambor’s faulty air conditioners, the crew headed for the beaches, the bars, and the brothels. They had survived, and they knew they would go back to sea as soon as the sub was ready, so they made the most of their few days of R & R at the Royal Hawaiian in Honolulu or, later in the war, at the Ocean Beach or the King Edward in Perth, Australia. The women, too, seemed desperate, thrown by world war into a time apart in which they took their chances as they came along.

Bob and his crewmates were young, and they had been flung across the globe to live and die. They lived hard when they could, and Bob lived as hard as any, drinking and womanizing and brawling. The fight against the Japanese at sea depended upon discipline and strict adherence to the routines instilled by rigorous training. In the forward room the torpedoes were serviced periodically—a delicate operation—and the tubes were complicated machines with banks of switches and valves to operate in precise, wild choreography during an attack. Confined as much by the concentration their tasks required as by their watertight compartments, the men cut loose pent aggression on leave, using their fists. After a fight with another sailor outside a bar on Pearl, Bob was taken in by the women in a house he frequented, who bathed him, put him to bed, washed the blood out of his clothes, and hid him from the MPs until morning. From that point on, according to time-honored custom, the man he fought, another submariner, was a lifelong friend.

And then there was sex. Before the brothels in Hawaii turned to assembly-line service stations, Bob visited a particular woman—a White Russian he was told by older crewmates— between patrols. It was a great relief, he told me, to lie in her arms. “I remember we would be in bed and she would say, ‘Was it bad this time, Bob?’ She was a real friend.”

There were other wartime companions in Hawaii and western Australia. Bob told me about a girl in Australia who thought he was an American cowboy and whose neighbor, a sheep rancher, asked him to ride an unbroken horse. The girl was a beauty, so he jumped on the horse, despite misgivings, and crashed it into the house. But in keeping with a firm resolve, based on the assumption that he would not survive the war, Bob made no commitments, wrote few letters, and made no dates that assumed a return he knew was always in doubt.

Life On Board

On board, Bob credited the nearly nonstop poker games as a source of his endurance. “Boy, the poker—that was real important. It kept me going.” He served his watches, slept, and played poker, sitting always with his shoulder leaning against the galley bulkhead below the pinup that overlooked the crew’s mess. In the game within the game of war, he found a place where he could play the odds and win. For many of the crew, including Bob, playing became compulsive. Sometimes they had to pause, not because the heat and humidity of a long dive stopped them, but because the cards became too damp and thick to shuffle. Bob found few equals at the poker table and sent his winnings home to his dad between patrols, enough to buy a small Iowa farm.

William James, in The Varieties of Religious Experience, famously described the disciplines of the saintly life as “the moral equivalent of war,” referring to the devotion of one’s entire self—and disregard for the body’s fate—required by the committed warrior. Robert Hunt, by his own candid admission, was no saint, but James’s description of devotion fits Bob, his fellow submariners, and many others who committed themselves wholly to winning a desperate war, the outcome of which often appeared very much in doubt.

After the War

Then, when the war was won and Bob had survived, he changed his life utterly. Before his discharge he wrote to his brother and dad, making plans for the afterlife. He returned to Iowa, went into the hardware business with Dick, and began dating Barb Parrish, a girl he had known in high school. They married and moved to Decorah, where Barb edited the newspaper and Bob ran the Hunt Variety Store. Bob and Barb went fishing and drove the countryside for the sheer pleasure of it. “After the war it was liberty with no going back. Just driving a car with the windows down was a great thing. Sometimes I even sang when I drove, or Barb and I sang together. It was something I’d never done before.”

They raised two boys, and the oldest, David, told me, “I know all the stories. Dad’s told me all about it. But I never knew that man. He’d drink a beer once in a while—one, maybe—and he and Mom were devoted to each other.”

When the couple celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary in 2006, Barb was confined to a wheelchair and living in the Aüse Haugen Home, and Bob had taken a small apartment across town. Every day he went over, riding his bike when the weather was good, and ate breakfast and lunch with her. “She needs some help, and it’s nicer if I can do it,” he told me.

“Between us, she was always the brains of the outfit,” Bob said. “And she was beautiful. Not like a cover girl. I mean, during the war I went out with girls that were beautiful. And Barb was good looking. But she was—she still is—a beautiful person.” Barb died in 2008.

Remembering the War

When I met Bob in 1985 he and Barb still lived in the tidy, ranch-style house with the white siding and red brick front. In the summer I would see him in his yard, wearing a sweat suit in the 90-degree weather, something I understood only after hearing about the 130-degree temperatures inside the Tambor when it operated in tropical waters without air conditioning. Then it seemed to me that his body’s thermostat had been permanently readjusted during the war.

When we spoke of making a book together, Bob took me to his basement study, an unfinished room with concrete floor, exposed pipes and wires, bookshelves, and a desk lit from above by bare light bulbs. Outside the sunken window wells and the tiny basement windows, the upper Midwest stretched all around, a vast inland sea. Perfectly at home, he pulled binders from the shelves and opened them on the desk. They were filled with photographs ranging from his enlistment to the present, with clippings from Polaris, the sub vets’ newsletter; with drawings and documents; and with letters from former crewmates or their wives, sons, or daughters. As I flipped the pages the men aged.

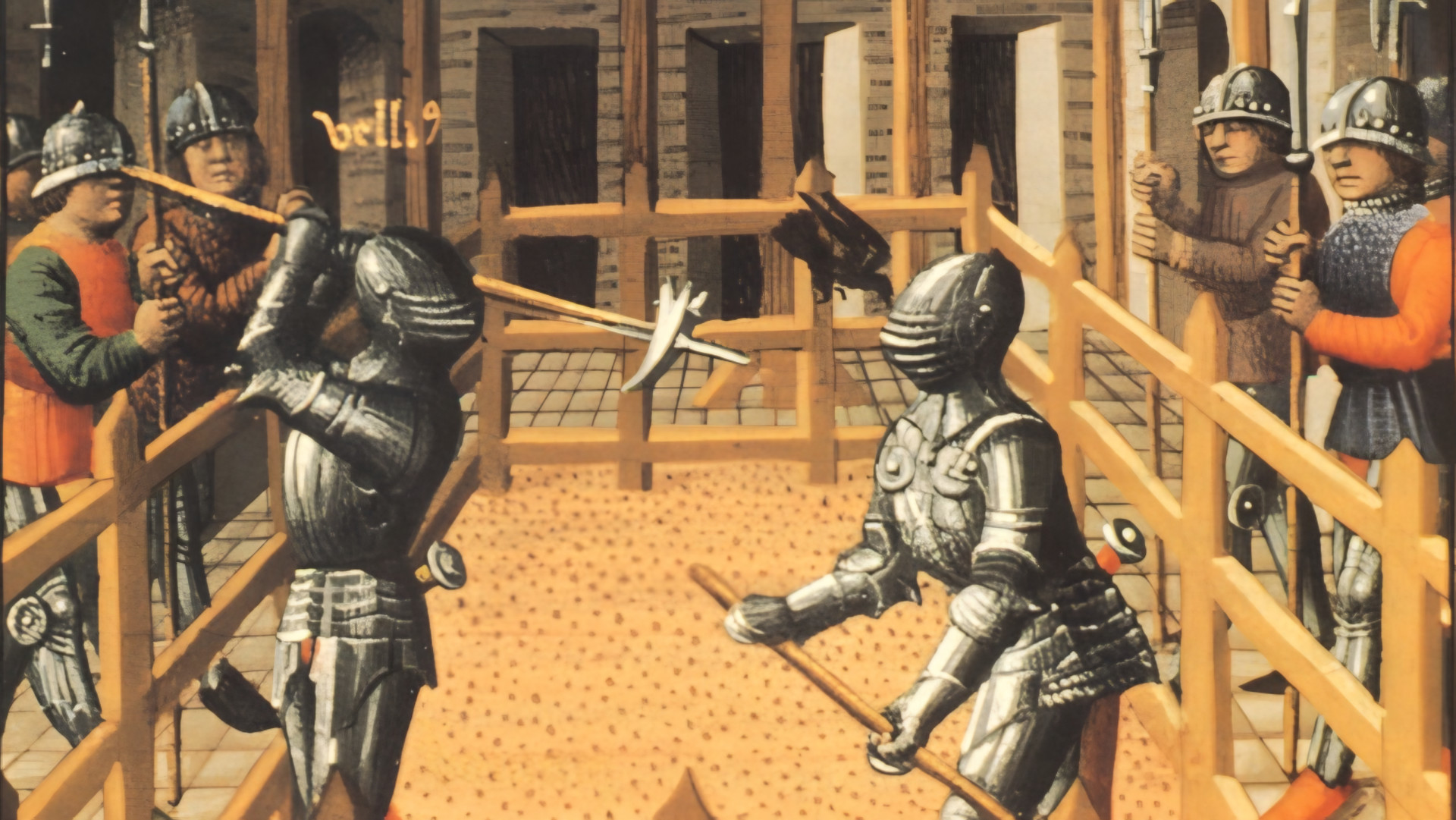

We paged together through the Life magazine that came to Bob and Barb’s house in 1946, bringing an article on the Battle of Midway that included images mocked up to represent its key moments. One of them depicted the Tambor surfacing near the Japanese heavy cruisers. “That’s when I learned that the two ships had collided because of us,” Bob said. “That’s the first I knew about it.”

Even as Bob had lived his postwar life as businessman, husband, and father, he had reached back in a sustained act of memory, eager to fill gaps in his knowledge of what he had lived through. These acts of reconstruction informed the yearly visits Bob made to area schools to talk with students about the war in the Pacific and his role in it. Some of the binders on the shelves around us contained materials for these visits, and he always took along a big map charting the Tambor’s missions, noting with color-coded dots the sites of depth chargings, aerial bombardments, sinkings, and surface battles. If repetition eventually outweighed analysis, it was because the magnitude of remembered events eclipsed the view of more distant causes. And Bob’s wartime experiences could hardly have been more mind filling: living in a metal pipe in the middle of the ocean, a small boat alone thousands of miles from home, men confined together in cramped compartments for two months at a time, hunting and killing, literally under pressure (“Pressure in the boat,” the diving officer would call). And then two weeks of utter freedom in a strange place, cut loose from normal time, awash in gratitude for sunlight and touch, for another survival, at first exhausted but then effervescent with bottled-up sex and fear and anger. For two weeks they would purge and rebuild themselves, seeking what they felt they needed. Then out again and back to the fight, because this was the work of their time, the time of their youth.

When I still lived in Decorah and when Bob and Barb still lived in their house two doors up, I would go for walks, climbing the Pine Street hill, descending the other side to the edge of town, passing the small pasture where two horses grazed. If I had stuck a carrot in my back pocket they would come to the fence to eat it from my hand. Then I would climb again to hilly Phelps Cemetery and circle among the headstones before returning home.

Coming and going, I passed Bob’s house, and often in the year when, at my instigation, he was writing down his memories I saw through the tiny basement window a single bare light bulb burning in what I knew to be Bob’s room. I always pictured him there, in that unfinished space, its exposed pipes, wires, and insulation, surrounded by his maps, notebooks, and photos, submerged again in that past time.

I did not stop to go in and see him, but as I walked on part of me stayed there, wondering at the submariner at home, underground in Iowa, remembering. And I wondered myself at a life so marked by early experience. When the war ended Bob was 26, and everything that followed—even love, marriage, children, career—would be aftermath. He might disagree, arguing for the primacy of his postwar life, and he would not use the word “aftermath,” but when I spoke to him and he told me one of the stories that stood so clear in his mind, his eyes widened and his voice took on a wondering tone, as if neither one of us should credit such a tale. And when he began, at my urging, to record his memories, he wrote in the third person about “Bob” and what “he” did.

It seemed as though the Robert Hunt that I knew, Decorah’s retired director of parks and recreation, looked back and saw another man, a self so distant now he could not claim him with the pronoun “I.” It was another life, strange to remember, and when he spoke of it his face took on a grin of disbelief that it had all really happened—hunting ships and men across the Pacific, being hunted, escaping into booze and women and fights on shore, his hands shaking from too much drinking, too little sleep, or something else.

He stood before me, the longtime husband of Barb, the fit retiree who rode his bike around town with a tennis racket strapped to the back, the man who, a few years earlier at the age of 75, had shown my daughter how to downhill ski at the rope-tow hill over by the college. Here he stood, in the shade of a big walnut tree beside my driveway, telling me stories from another life 60 years in the past.

His past had become the great romance— they set ships on fire in the middle of the sea; they had parties all over the world. I wondered that he had emerged from those years on the boat so apparently unscathed. When he wrote down his memories the blunt sentences seemed unshadowed, one story leading to the next in an associative flow in which cascading events left no room for reflection. Once, when he used the word “flashback,” I asked him what flashed back, expecting a patch of darkness. But he said, “The things that come back are the things I like to remember—the parties, the sex.”

The darkest aspect he ever showed me was the set jaw and straight gaze when he spoke of his friends who had been killed. Then I glimpsed the resolve and simmering anger that saw him through, that kept him going out, and that provided the big story his generation shared. America had been attacked, they had set all aside to avenge the wound and defeat the aggressor, and then they had gone back to live their lives. The war was an interruption, and they had put it behind them with a resolve like that with which they had fought.

But Bob kept going back. Eleven times during the war he returned to that forward room, to the bunk that pulled out from under a torpedo, where he heard water rushing past and the bow plane motors, and felt secure. At home in Iowa he went downstairs to the archive room and back in time. And lately, in his snug apartment, in the blue bedroom where we huddled for our interviews, he remembered again, descending once more into the past.

Wow! Great story!

Wow! What those men did for our country, the hundreds of thousands who did not come home and the millions who carried their scars all of their lives.

David Seeds