By Christopher Miskimon

Corporal Michael Kurtz stood on the deck of an attack transport ship sitting off the Normandy coast. Gazing out over the ship’s railing in the pre-dawn hours, he could see the ship’s crew working the davits and ropes for the landing craft. Within minutes, his squad of riflemen, part of the 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, would climb aboard one of those small boats and head toward their objective, a strip of beach code-named Omaha.

As their turn neared, Kurtz gathered his squad around him. “I want all of you Joes to keep your heads down,” he said. “As soon as we’re spotted, we’ll catch enemy fire. If you make it, okay. If you don’t, it’s a hell of a good place to die. Now let’s go.”

Minutes later they were climbing over the rail into their assigned landing craft. Just then, the davits supporting a nearby boat broke. The entire thing flipped and tumbled into the sea, dumping all 30 men aboard into the cold waters.

Kurtz’s landing craft reached the water without trouble, bobbing next to the transport. The men who were dumped into the sea from the other craft were all around, swimming to stay close to their ship and await rescue.

As the sailors manning Kurtz’s boat started moving it slowly toward shore, one of the GIs in the water called out, “So long, suckers!” Looking around at his men, he noticed all of them held blank expressions on their faces, their thoughts betrayed only by the look of tension simmering beneath each visage. The landing craft picked up speed, heading toward Omaha Beach.

Cracking the shell of Fortress Europe meant someone had to be the tip of the spear. On June 6, 1944, the 1st Infantry Division filled that role, alongside several other American, British, French, and Canadian units assigned to be the first ashore. They were reinforced by follow-on divisions and enjoyed the support of a vast air and sea armada, the biggest yet seen in history.

Still, until the troops got ashore in force and secured their initial objectives, the success of the whole endeavor was in doubt. Every detail of the operation, code-named Overlord, had received years of meticulous attention from planners and staff officers to give it the best chance of success. In the end, whether Overlord succeeded came down to the courage and actions of the few thousand men who had to hit the beaches first.

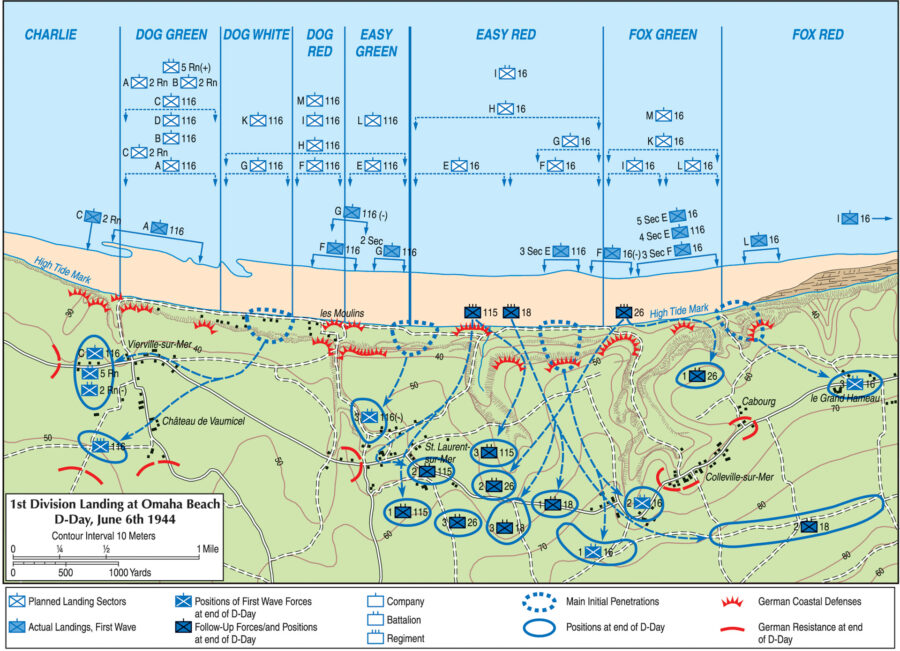

The 1st Infantry Division bore the nickname “Big Red One” after its distinctive shoulder patch: a large red numeral one on a green background. The unit contained three infantry regiments: the 16th, 18th and 26th. Each regiment had three battalions, each with three rifle companies, a weapons company, and a headquarters company.

Engineers, tanks, and naval shore parties would accompany the infantry ashore to help them break through the solid German defenses and move inland. For the assault on Omaha Beach, the Big Red One was joined by the 29th Infantry Division, a National Guard unit originating in Maryland and Virginia.

The landing plan called for different, complementary units to arrive at the shore in a coordinated sequence. A fixed schedule determined when each unit would arrive, ideally allowing time for that unit to complete its mission and move inland to make room for the next wave.

The first Americans to hit Omaha were supposed to be the crews of 32 Sherman Duplex Drive (DD) tanks, timed to arrive at 6:20 am. These DD tanks from the 741st and 743rd Tank Battalions were to reduce the beach defenses with cannon and machine-gun fire for 10 minutes.

At H-Hour (6:30 am), another 32 tanks and 16 tankdozers from the same unit should arrive and add their firepower to the melee. The tankdozers would use their specially fitted bulldozer blades to clear the obstacles laid across the beach. The schedule called for the 2nd Ranger Battalion to land with the second group of tanks.

Planners selected the 16th Infantry Regiment to act as the division’s spearhead at Omaha. Their plan called for the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 16th (2/16 and 3/16, respectively) to hit the western end of the beach in designated sectors one minute after the second group of tanks. Companies E and F of 2/16 would land at Easy Red sector, while Companies I and L of 3/16 would hit Fox Green sector.

G and H Companies of 2/16 and K and M Companies of 3/16 were to land right behind the other companies of their battalions, about a half hour later. 1st Battalion (1/16) would come ashore at H+70, just over an hour later. At H+90 the division headquarters would join the 16th, followed by the 18th Regiment spaced out between H+195 and H+210. The 26th Regiment would arrive in the early afternoon, with many thinking the 26th would only have to mop up behind the other two regiments. Accompanying the first assault waves were combat engineers trained to clear obstacles.

While these assault waves received the best planning and support the Allies could provide, there was no way to foresee every possibility. When two groups of skilled and implacable enemies meet, success depends upon determination, courage, and ingenuity. Even luck becomes a factor. It is a military cliché, though a true one, that “no battle plan survives contact with the enemy.” The plan for Omaha Beach would not survive contact between the Americans and Germans, either. When that plan failed, as they always do, the soldiers of the Big Red One still had to accomplish their mission, take the beach, and move inland.

The journey into the beach was a harrowing experience itself, though nothing compared to what followed. The water seemed against the GIs that morning, rough seas rocking the landing craft with waves depositing water over the sides, drenching the soldiers and making the boats harder to manage.

Before long, men started to throw up their breakfasts, quickly filling the one seasickness bag they were issued. Lt. James Watts, A Company, 81st Chemical Mortar Battalion, recalled, “I was fighting desperately to avoid being seasick in front of the men. Somebody said we were eight or 10 miles out. That’s a long, long way to go.”

As the leading waves of assault craft neared shore, they encountered enemy fire. Corporal Jess Weiss of 2/16 recalled the experience. “As we neared shore, 155mm howitzer shells began to rain on us from above. I could hear crossing bands of intense and accurate machine-gun and mortar fire hitting the water and the heavy metal hull of the LCT [Landing Craft, Tank], from stern to bow.”

Weiss had seen combat in North Africa and Sicily, where he’d learned how to react to artillery fire: “I crouched down and hugged the bottom of the LCT, seeking whatever protection its metal hull could provide.”

Nearby, several men who had not yet seen action were excited by the explosions and noise. To get a better view, they climbed on top of several jeeps strapped down in the center of the LCT. Weiss saw them and shouted a warning. “I screamed to them, ‘Hit the deck!’ But it was too late. German artillery decapitated two of them, and several others were severely wounded.”

Behind the GIs, Allied warships fired salvos of high-explosive shells at the shoreline. Overhead, hundreds of bombers flew over the beach to drop their ordnance on the waiting Germans. Landing craft converted into rocket launchers disgorged their weapons onto the beach. All of this was to pave the way for the DD tanks to get ashore and demolish the remaining defenses as the infantry arrived at the shoreline.

Unfortunately, none of it went as planned. The naval gunfire and air strikes landed inland, over the heads of the Germans in their bunkers and strongpoints. The rockets were likewise ineffective. Most of the DD tanks assigned to the division’s sector sank in the Channel when the heavy waves overcame their flotation screens; only six of the 32 tanks made it to shore.

The bombardment plan called for the gunfire to tear gaps in the beach obstacles and blow craters in the ground to provide cover for the troops as they advanced. A few sailors and Army engineers formed into underwater demolition teams managed to blow a few lanes in the obstacles, but in the chaos the buoys used to mark the lanes were lost.

The division artillery even mounted howitzers on DUKW amphibious trucks, but most of the guns were knocked out by enemy fire or the rough seas. The failure of the fire-support plan meant the German defenses sat intact and waiting for the Americans as they neared the beach. There were not even any craters the GIs could use for shelter.

Lt. Col. William Gara commanded the 1st Engineer Combat Battalion. As his landing craft churned toward shore, he spent the two-and-a-half-hour journey worrying whether his boats would find their assigned landing sectors. The din of gunfire rang through the early-morning air as they arrived about 300 yards offshore. He recalled, “We could see that things weren’t going well … the paths and gaps between the underwater obstacles had not been opened, and so we recognized we were very likely going to get blown up.”

The overcast skies prevented the warships from realizing their fire was going long. At the same time, the current and the wind forced most of the boats off course, so most of them landed east of their assigned area.

Steve Kellman, L Company, 3/16, was supposed to land on Fox Green but wound up east of Easy Red. When the ramp on his boat dropped, the men aboard raced for shore as German fire struck all around them. Kellman was assigned as a rifle-grenade man, but he also carried an aluminum ladder broken into two sections, so it was easier to carry. The ladder was for crossing a tank trap at Fox Green. As soon as Kellman realized he was on the wrong beach, he threw the ladder away.

German machine guns raked the GIs as they struggled to get ashore; artillery and mortars blasted them while they moved among the intact beach obstacles carrying heavy burdens of weapons and equipment.

Captain Ed Wozenski commanded E Company, 2/16. As his boat neared the beach, machine-gun bullets started bouncing off the ramp. When the boat hit bottom, the ramp refused to fall. A team of soldiers knocked it open and fell with it. The rest of the men hurried out into shoulder-deep water. After the boat emptied, several hits set it afire. Wozenski’s men strode slowly toward the beach on the seabed; the current and their burdens made it impossible to do more than walk.

“It was just a slow, methodical march with absolutely no cover up to the enemy’s commanding positions,” Wozenski noted. “Many fell left and right, and the water reddened with their blood. A few men hit underwater mines of some sort and were blown out of the sea. The others staggered on to the obstacle-covered, yet completely exposed beach … The survivors still moved forward and eventually worked up to a pile of shale at the high-water mark. This offered momentary protection against the murderous fire of the close-in enemy guns, but his mortars were still raising hell.”

F Company, under Captain John Finke, came ashore next to E Company. They landed at 6:40 am under the same deadly fire as their comrades. Finke noted, “The assault teams had to wade across 30 yards of water under fire and cross a beach of approximately 130 yards under the same fire. The cost in casualties was six officers and 80% of the company.”

Amid this confusion, two boat sections from the 29th Division’s 116th Infantry, badly off course, landed among the men of the 1st Division. Part of F Company, spread out across a thousand yards, managed to get close to the E-3 draw, an exit point from the beach, but it was heavily defended, and the company suffered over 50% casualties within minutes.

Some soldiers made it to the shingle, also called the seawall—a small rise composed of small stones gathered by centuries of tidal activity; it provided a tiny amount of cover. From their widerstandnest (“resistance nest”) strongpoints, the Germans threw grenades down on the GIs, hoping shrapnel would reach where their bullets could not.

Meanwhile, the boats carrying I and L Companies, 3/16, had strayed more than a mile off course, almost to the British sector. The crews struggled to get back to their original landing areas, but Captain John Armellino’s L Company wound up coming ashore a half hour late at the eastern edge of Fox Green near some low cliffs extending almost to the waterline. These provided the weary GIs some cover.

Steve Kellman was one of those men. His boat managed to get close to shore, so the GIs could run through knee-deep water to the seawall. He and his comrades flopped down, exhausted, and watched another boat’s men struggle to the beach and take cover behind the obstacles. Their boat did not get as close to shore. L Company suffered 50% casualties but had landed as a unit. This allowed Armellino to start organizing an attack to get off the beach through a draw labeled “F-1” on the map. Before they could move out, however, the captain was wounded.

“It was like all hell had broken loose,” Kellman recalled. “There was noise and smoke and dead bodies all over the place.” The GIs knew they were in the wrong place and started moving toward their assigned beach. As they went, an enemy shell exploded in front of Kellman and another man, knocking them both backwards. Kellman crawled to the seawall, but when he tried to get up and move further, he fell back down. After falling again, he checked his legs and found one bloody and numb.

He poured a sulfa packet on the wound and bandaged it. Unable to continue, he gave his rifle and grenades to other soldiers and lay there talking to the other man, also wounded by the same shell. A lieutenant came by and promised to send an aid man, but hours went by, with artillery fire landing the whole time. After a particularly close explosion, Kellman asked the other wounded man how he was doing, but the man was dead.

Lieutenant Robert Cutler assumed command of L Company for the wounded Armellino. He could see two enemy strongpoints, WN 59 and 60, preventing his company from exiting the beach using the E-1 draw. He ordered Lieutenant Jimmie Monteith to assault WN 59 and Lieutenant Kenneth Klenk to attack WN 60. Each officer rounded up what remained of their platoons and moved out.

The boats carrying Captain Kimball Richmond’s I Company finally returned to Omaha Beach and came in under heavy fire. Gunfire hit Richmond’s landing craft and it began to sink. He dove overboard and waded ashore with his company. On the beach he quickly assembled what he could find of his men, along with whatever stragglers he came across. Together, they moved toward a beach exit and ran into an enemy strongpoint. Rather than getting pinned down, they attacked and wiped out the German position, the first success of the morning.

As the leading assault waved floundered on the beach, behind them troops from their regimental headquarters and supporting artillery began to land. One of the artillerymen, Eldon Wiehe, immediately got separated from his unit and was then almost killed by a German shell. “I guess I panicked,” he later said. “I started crying.”

Some GIs grabbed him and pulled him behind a landing craft that had run aground. “I cried for what seemed like hours. I cried until tears would no longer come. Suddenly, I felt something. I can’t explain it, but a feeling went through my body, and I stopped crying and came to my senses.” Able to think once again, Wiehe grabbed a rifle and moved forward.

K Company also came ashore; intended as a reserve company, they joined the fight as soon as they landed. Pfc. Roger Brugger remembered running straight off his landing craft onto the beach, where bullets kicked up sand to either side of him. He ran to the seawall and took cover. When he looked back, he saw his landing craft take a hit and explode. Another boatload of men ran onto the beach and toward Brugger.

The K Company commander, Captain Anthony Prucnal, died from an artillery shell as he tried to help his wounded executive officer, Lieutenant Frederick Brandt. Two other lieutenants were killed or wounded trying to rally the company. Finally, Lieutenant Leo Strumbaugh put together a group and led them against a German position through heavy fire, forcing the German defenders to retreat. It was another small victory, paling in comparison to the heavy casualties the GIs were taking, but each such triumph helped get them closer to the beach exits.

The GIs pinned along the seawall stayed as low as possible to avoid the enemy gunfire, though the artillery and mortars, with their plunging trajectories, could still get them. A few men peered over the wall toward the next impediment to their advance, a thick layer of concertina wire, beyond which lay minefields.

The troops could use Bangalore torpedoes, a pole-like explosive charge assembled into long sections and pushed into the mass of wire, to blast holes through the obstacle. They could probe the minefields and push their way across. To do so meant braving the heavy fire already landing around them. Only a few intrepid soldiers had tried; getting off the beach required a concerted effort by well-led groups. So far, the efforts of a brave few proved insufficient.

As more soldiers piled up behind the seawall, landing craft carrying 3/16’s Headquarters Company approached the beach. Among them was Lieutenant Karl Wolf, who suffered seasickness on the trip in. A soldier gave him Dramamine tablets to help, but Wolf did not know how many to take, so he swallowed three of them.

When his boat reached the beach, he ran out into the maelstrom. The battalion adjutant, Captain Al Moorehouse, died just a few feet behind Wolf, struck by a machine-gun burst. The young lieutenant took cover behind a beach obstacle, next to two other soldiers. He tried to locate the source of the machine-gun fire to give him an idea of which way to move up; just then a burst stitched a line in the water, killing the other two soldiers, who floated away with the tide.

Wolf ran for the shore. He did not know where he was; none of the beach features looked like those in the invasion briefings. Suddenly, Wolf noticed the patches on the men around him were for the 29th Division. Like so many others that morning, he had landed on the wrong spot. Wolf watched men get hit all around him as he reached the cover of the seawall. On the water, a Landing Craft, Infantry (LCI), a larger vessel, stopped too far out. Wolf watched at least 10 men drown before the craft’s captain realized the situation.

With Captain Moorehouse dead, Wolf realized he had to take charge of the men from his boat. He gathered the 12 survivors he could find and started down the beach to rejoin his battalion. As they made their way, enemy fire forced them to occasionally lie flat on the beach and wait until it lifted.

Meanwhile, men began trying to get Bangalore torpedoes and wire cutters up to the concertina wire beyond the seawall. A few men tried, but all were quickly killed. Finally, Sergeant Phillip Streczyk of E Company decided to try. He sprinted for the wire with machine-gun fire hounding him. Despite this, he reached the concertina, cut a hole through it, waved for the men at the seawall to follow him. He later received a Distinguished Service Cross for his bravery.

Another man who got things moving that morning was Lieutenant John Spaulding of Kentucky. E Company had already lost 100 of 183 men, but Spaulding gathered the rest and set off through the gap Sergeant Streczyk had created, intent on taking the enemy strongpoint east of exit E-1; Captain Joe Dawson’s G Company laid down covering fire for E Company’s move.

Spaulding’s GIs crawled forward under heavy fire to reach the gap in the wire. Getting through it, the lieutenant led them against the strongpoint, which poured machine-gun fire at them. The Americans crept under the bullets snapping past mere inches above them until they were close enough to throw hand grenades at the Germans, who threw back some of their own. A sergeant tried to hit a machine-gun nest with a bazooka but missed and was wounded in return. Finally, the GIs got close enough to one of the machine guns and that crew surrendered.

One of Spaulding’s men, a sergeant carrying a BAR he found on the beach, went through 20-round magazines so quickly a soldier had to follow him carrying spare ammunition. Medic George Bowen and his fellow aid men moved constantly, providing help to the many wounded.

“No man waited more than five minutes for first aid,” recalled Spaulding. He credited Bowen with helping keep up morale. Finally, 1st Platoon cornered 20 Germans and their officer, who wisely chose to surrender. Spaulding earned a DSC for his leadership in taking the strongpoint.

Captain Dawson brought G Company through the gap next. He knew minefields lay in front of his position, but spotted a narrow path leading up to an opening at the top of the bluff above. “I felt the obligation to lead my men off, because the only way they were going to get off was to follow me,” Dawson said. He started up the path with a sergeant named Cleff and Pfc. Frank Baldridge.

Partway up, he ran into Lieutenant Spaulding, who had about two squads left. At the time, Dawson thought they were the only survivors of E Company. The rest of G Company still sheltered behind the seawall, so Dawson sent Baldridge back to bring them up. Near the crest of the bluff Dawson found a log and took cover behind it to see if he could spot his men coming up.

Sure enough, he saw a line of GIs start to come forward, but suddenly a machine gun fired on them. The captain realized the gun was emplaced just above him on the bluff, so he started crawling toward it. He got to within a few yards and pulled a few grenades off his belt. He threw them one after another and the gun went silent. His brave act allowed his men to continue up the path.

As the scattered actions of junior officers and NCOs began to make a difference, the 16th’s next wave approached the beach. Tragically, as 1/16’s landing craft arrived, most of the previous wave’s survivors still lay pinned along the shingle seawall or huddled behind obstacles. The newly arriving GIs had nowhere to go but to crowd Omaha further, providing more tightly packed targets for the veritable murder machine of German machine guns, mortars, and cannon.

Sergeant Harley Reynolds of B Company remembered waiting in his landing craft as it neared the shoreline. “There wasn’t much conversation. We were listening to all that small-arms fire and swapping glances. We knew we were in for a hot reception.”

Reynolds noted his boat’s crew had to steer around and between the wrecks of other craft. He saw bodies floating in the water and bobbing in the surf. Despite the heavy fire snapping past, he was surprised by how few bullets actually hit his landing craft. Some soldiers stayed in the water, only their heads above the surface, unable or unwilling to move up.

Unarmed, Reynolds thought of them as useless, doing nothing but getting in the way. As his boat’s ramp dropped, he told his squad leaders to fan out and head in. Reynolds went first, off the ramp and dodging to the right with his radioman, Private Tony Galenti following. A burst of machine-gun fire struck home and Galenti fell, his radio shattered. He never made it off the ramp. Reynolds took cover behind an obstacle.

“I knelt by the obstacle to look around … While crossing the beach, I felt tugs at my pants legs, several times. Later, I found too many rips and tears to identify any as bullet holes,” Reynolds said. He saw bullets impacting all around him. “I believe the bullets were coming from a long distance, as they seemed to have lost some of their energy and I could hardly hear their hissing sounds.”

John Bistrica of C Company took cover behind the shingle as well. He felt as if “the whole world was coming in on me.” A soldier next to him called out, “I’m hit. I can’t breathe.” Bistrica realized the man’s life preserver had tightened on him and cut off his air. “So, I got out my knife and jabbed a hole in it. He was okay after that.”

The 1st Battalion men soon mixed in with the rest of the regiment on the beach, huddled together in the scant cover of the shingle. Corporal William Lynn threw himself in with them. Next to him lay a decapitated GI, his dogtags missing. Lynn took his shelter half from his pack and covered the body before moving on.

At 8:30 am, a Navy beachmaster managed to get a message to the fleet warning them to send no more landing craft to Omaha Beach. It was simply too crowded with wrecked vessels and the beach too packed with trapped soldiers; there was no more room for the following waves of men.

The Navy command also realized their shore bombardment had been ineffective, but it was still desperately needed to help turn the tide against the Germans. The battleship Arkansas stood offshore, ready to deliver lethal broadsides of 900-pound 12-inch shells, but she was too large to get close to shore for pinpoint accuracy. Instead, eight destroyers moved in as close as 700 yards from Omaha—point-blank range for a warship. They aimed their 5-inch guns at the bunkers and pillboxes overlooking the beach and opened fire.

Several soldiers remembered the effect this had for the soldiers. Major Kenneth Lord recalled, “Their keels must have hit bottom. It was the greatest help that we had the entire day. They were instrumental in breaking through the beach defenses.”

Lt. Col. William Gara, 1st Engineer Combat Battalion, described the action: “There were naval gunfire teams on shore; by radio they directed the ships to come closer to fire at the pillboxes … They lowered their 5-inch guns and began shooting … They were our only supply of artillery for the first four hours on Omaha Beach.” Other senior officers credited the Navy with enabling the division to get off the beaches that morning.

Don Whitehead served as a correspondent at Omaha Beach. He spent much of the morning worrying the Germans would counterattack the beach and drive the beleaguered Americans back into the sea. Despite the carnage all around him, he realized the time for such a move had passed. He wrote, “Our Navy was pouring a murderous fire into the enemy positions. From the beach, too, disorganized as it was, there was a steady stream of small-arms and machine-gun fire … and the thumping of mortars lobbing shells onto the bluff.”

As the junior leaders acted to get their men moving, a senior leader got the beach organized. Brig. Gen. Willard Wyman, the assistant division commander, landed on the beach both to get the 1st Division assault troops moving inland and to coordinate with the neighboring 29th Division.

With almost suicidal bravery, Wyman disregarded enemy fire and calmly walked around the beach, assigning missions to groups of soldiers, and moving units to their assigned positions for the push inland. He sent messengers up and down the narrow strip of beach the Americans held to get his troops coordinated.

The 16th Regiment’s commander, Colonel George Taylor, did likewise, bringing order from chaos and getting his troops moving, in part because he was angry so many of them were doing little other than taking cover. In his efforts to get them moving, he uttered one of the most famous phrases of the war: “There are two kinds of people who are staying on this beach—those who are dead and those who are going to die! Now let’s get the hell out of here!”

More lanes had to be opened through the wire. Sergeant Harley Reynolds saw a small man creep up to one section of wire with a Bangalore torpedo, assemble it, and light the fuse. It sputtered, so the man calmly replaced it and lit another. As the man crawled backwards, he suddenly flinched, looked directly at Reynolds, and died. The torpedo exploded a moment later, blowing a large gap which Reynolds and several other men dashed through.

Reynolds moved so fast he dove through an unbroken section of wire without a scratch, then came to a water obstacle which he swam across. In other places, men found the small paths which wound around the ponds and minefields and went up toward the top of the bluffs.

Platoon Sergeant John Ellery of the 16th watched a captain and two lieutenants lead groups of men up a narrow path, even though one of them had a broken arm. Two of the officers were soon hit. Reflecting on those men, Ellery later said, “When you talk about combat leadership at Normandy, I don’t see how the credit can go to anyone other than the company-grade officers and senior NCOs who lead the way. We sometimes forget that you can manufacture weapons and you can buy ammunition, but you can’t buy valor and you can’t pull heroes off an assembly line.”

More heroes arrived on the beach in the form of bulldozer operators. Sixteen of the heavy engineer vehicles were sent to Omaha to assist with clearing obstacles and making a path for tanks and other vehicles to get onto the high ground beyond the shoreline. Only six made it to shore, and three were soon knocked out.

Reporter Whitehead watched Private Vincent Dove calmly use his bulldozer to start making the first path off the beach for the tanks, despite a complete lack of protection from enemy fire. Dove drove a bulldozer for 15 years before joining the Army and deftly used it to clear a lane.

Corporal William Lane saw a bulldozer driver raise the blade to protect himself from enemy fire and move forward. However, this kept the driver from seeing a wounded soldier in the way of the vehicle. Lynn was about to dash out to help the wounded man when Lynn’s lieutenant shouted, “You go for him and I’ll have you court-martialed!”

Lynn replied, “Court-martial me when I get back!” and took off at a run for the stricken man. He waved off the bulldozer operator and then applied a tourniquet and used a rifle to splint the wounded man’s leg. Lynn paused to give the casualty a syrette of morphine before picking him up and carrying him toward the surf, hoping to put him on a departing boat.

The boat’s crew refused to help, leaving Lynn in neck-deep water with the casualty draped over his shoulders. Another landing craft did help—coincidentally the same one Lynn arrived on! They took the wounded man and Lynn went back to the beach. The lieutenant declined to court-martial him.

Lt. Col. Gara’s men worked steadily to clear gaps in the minefields, and by 9:00 had blown several gaps, marking them with tape, and in some cases toilet paper. A few precious tanks arrived with the bulldozers, and their commander tried to get them off the beach to support the infantry, who were finally getting to the top of the bluff to reduce the enemy defenses. Gara wanted all of them off the beach so his men could start eliminating the minefields and filling in the anti-tank ditches.

As Gara and his men kept working, the landing craft carrying the next wave of troops, the 18th Infantry, appeared behind him, coming out of the smoke and mist hanging over the water. Most of the first waves were still stuck on the beach, however. The 18th landed amidst the twisted wrecks of destroyed landing craft, knocked-out tanks, the dead and the dying.

Pfc. Ralph Anderson served as a BAR gunner in E Company. He lost his weapon in the surf but went back to retrieve it under fire. He had to clean it three times to get it working. Afterwards, Anderson and another man crawled up the slope past a German pillbox. They got past the strongpoint just before a destroyer blasted it with several rounds. The destroyer Franklin pelted a strongpoint above Exit E-1, breaking the morale of the Germans inside.

Captain Oren Rosenburg’s F Company, supported by a single tank, moved up the slope and captured 20 enemy troops as they staggered out of the ruined bunker. G Company secured the entrance to E-1 while H Company moved up the path without taking a single casualty. Soon all of 2/18 had moved to the top of E-1. General Wyman ordered them to advance on the village of Colleville, a mission originally assigned to the now decimated 16th Regiment.

The opening of E-1 proved a critical moment for the 1st Division. Troops could now flow off the beach onto the heights above and start pushing inland. Engineers bulldozed a path alongside to allow the tanks, halftracks, and trucks to accompany the infantry. It was approaching noon, and, while the Americans were finally making some progress, their commanders waiting offshore knew nothing of it due to the continuing communications problems.

Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley worried all morning about the fate of the Omaha Beach assault. The other Allied operations had their own problems but overall were progressing well. Finally, he sent Major Chet Hansen ashore to find out what was happening. Hansen went most of the way on a PT boat before transferring to a landing craft 2,000 yards offshore. He got off in four feet of water and waded in.

Wreckage from the assault lay all around, mixed with the bodies of the fallen. The wounded were being tended to, but artillery fire still fell on the beach. Hansen watched one shell blow up a truck and send a GI’s lifeless body 30 feet into the air. Another soldier was thrown upward as well but recovered and kept moving. Hansen returned to Bradley and informed him of the tough fighting.

Despite the limited success in getting off the beach, Private Carlton Barrett of the 18th’s Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon landed among a storm of small-arms and mortar fire. He stepped off the landing craft into neck-deep water but pressed forward. After he got to shore, he went back into the surf to rescue wounded and drowning men, pulling them to relative safety.

Ignoring the deluge of incoming fire, Barrett carried the casualties to an evacuation boat before returning to help other wounded men, reviving those in shock and inspiring them to return to the fight. He carried messages up and down the beach for leaders trying to coordinate their attacks. His selfless and courageous actions resulted in the award of the Medal of Honor.

Other 18th Regiment men began moving off the beach through the lanes marked by engineers. “We didn’t stay on the beach too long,” said Ray Klawiter of D Company. “The engineers had cleared a path and marked it with toilet paper. If you stepped just a little off that path, you would get it.”

Mortarman Eddie Steeg focused on the man in front of him, ignoring the carnage on the beach as best he could. As they went up the cleared lane, two lieutenants veered off the path and stepped on mines. One died and the other lost a leg. Steeg paused only to pick up an abandoned Thompson submachine gun. “Not that I needed any more weight to carry,” he recalled; Steeg already hefted the bipod of an 81mm mortar. “I just couldn’t resist being the possessor of a real Tommy gun … Maybe I could now copy Jimmy Cagney and use the weapon to eliminate those ‘dirty rats,’ the Jerries.”

Even sailors joined the infantry on June 6. Robert Giguere served on a Landing Craft, Infantry (LCI) that made it to the beach but sank from enemy fire. He went ashore with the rest of the crew, getting a flesh wound in his shoulder along the way; he dressed the wound while hiding behind a beach obstacle. Making his way ashore, he spent some time helping wounded men get out of the water.

Giguere noted, “I have never seen so many wounded, dying, and dead. I never saw such a mess—trucks, jeeps, tanks, halftracks burning everywhere.” He crawled through a gap in the wire and ran into an Army lieutenant who gave him two hand grenades, perhaps mistaking him for an unarmed soldier.

Giguere crawled a hundred feet to a German bunker pouring machine gun fire down onto the beach and threw both grenades into the embrasure. Nearby GIs tossed him more grenades, so he pulled the pins and threw them in, too. “I must have thrown six to eight grenades and got the hell out of there in a hurry because a destroyer was coming in to start shelling the gun emplacement.”

The mines and the wire still impeded the masses of troops from exiting the beach. Ted Aufort of 1/16’s Headquarters Company was stuck behind a thick stretch of wire with other troops. They assembled a long Bangalore torpedo and got it under all four or five rows of it before detonating the weapon, blowing the wire apart. They ran through, but mines awaited them on the other side.

“Sergeant Ford stepped on one,” Aufort said. “It blew the flesh off his legs and just the bones were exposed.” A friend serving as a stretcher-bearer was also wounded. “I heard a voice call out to me … He was laying there with a tourniquet on his arm, where his left arm was blown off and just a bloody stump was sticking out.”

Despite the heavy cost in men, each gap opened allowed more soldiers to get off the beach. L and M Companies of the 16th cleared out a German nest with help from I Company and a Sherman tank.

Harley Reynolds arrived at a German trench line and led a group of GIs to clear them. Boot prints lined the bottom, so Reynolds figured they were safe to walk through. He flipped off the safety on his rifle, which had a rifle grenade over the muzzle; he did not think there was time to take it off. He moved down the trench with the rifle grenade jutting out ahead of him. Luckily, there were no Germans around.

From this position, Reynolds saw Germans in another trench some 400 yards away, carrying something, perhaps ammunition. The GIs started firing at them with a machine gun, and Reynolds finally took off the rifle grenade so he could shoot as well. Several Germans were hit and fell; another fled into a bunker. As Reynolds watched, some GIs got to the bunker and threw grenades. A white flag appeared, and the Germans came out with their hands up. As the GIs dealt with their prisoners, Reynolds saw another group of enemy soldiers sneaking up on the distant Americans. Reynolds directed fire at this new group, which quickly surrendered as well.

As Lieutenant William Dillon of A/16th led his men uphill, he saw Sergeant Pat Ford step on a mine. It blew his leg off and threw him into the air. Ford landed on another mine which injured his arm and tossed him onto yet a third mine. Looking around for a way out of the mines, Dillon spotted a small, faint path. He cautiously went up, found it clear, and went back to show his men the way.

The fighting stayed grim and close as the GIs slowly ground forward. 1st Lt. Jimmie Montieith charged through enemy fire to get help from a pair of tanks before leading a patrol up the slope. Stopped by a German strongpoint, three of his men crawled through wire and minefields to destroy one enemy position. Monteith led the rest of his men through another minefield, marking it as they went, and reached the top of the bluff, where they joined some other GIs and dug in.

A sergeant sent a patrol toward the village of Le Grande Hameau, but it was forced back by heavy fire. Another patrol sent toward Cabourg was captured, but the two Americans convinced the Germans that resistance was pointless, and so the Germans surrendered to their own captives!

Meanwhile, the Germans counterattacked Monteith’s perimeter repeatedly, firing at him as he moved along his line filling gaps and directing his men. Soon the Germans surrounded them, so the Americans tried to break out. During that fight Monteith was hit and killed, but his bravery and leadership earned a posthumous Medal of Honor for the young officer.

Despite this setback, the men of the 1st Infantry Division were now getting off the beaches. At 1:30 pm General Bradley, waiting offshore for word of either success or failure, got encouraging news: “Troops formerly pinned down on beaches Easy Red, Easy Green, Fox Red advancing up heights behind beaches.” Omaha was still within German artillery range, but rifle companies were finally getting consolidated and moving off toward the villages a short distance inland from the beach.

Lieutenant Nelson Park’s troops reached the top and opened fire on a group of Germans, forcing them to retreat. Parks saw another lieutenant get hit while chasing the fleeing enemy, the round coming out his back. “I said, ‘don’t worry, Ben, we’ll get you out of here!’ I will never forget telling him that.” Parks said. “The truth, Ben was probably already nearly dead. I couldn’t do anything more because all hell broke loose and we had to charge ahead and just leave him there.”

The now-accurate naval gunfire battered the remaining German strongpoints, causing their fire to slacken. GIs got up and went at them, throwing grenades at machine-gun nests and following the explosions to mop-up. German troops tried to run out the back of their shell-blasted bunkers straight into the waiting American infantry. Some were killed, others taken prisoner.

The 16th’s G Company, under Captain Joe Dawson, set out for the village of Colleville-sur-Mer. A French woman came out to greet them, saying ‘Welcome to France.’ Dawson led his men into the village, attacking a church steeple the Germans used for artillery observation. He lost a man during the fight but killed the enemy observers. A few minutes later a sniper’s bullet hit the stock of his carbine, sending a wood fragment into his leg. He ignored the painful wound and stayed with his men. To cap off the day, at 4:00 pm a U.S. Navy barrage hit the village, unaware that the American had occupied it.

At the same time, German artillery fire evaporated. The enemy had finally run low on ammunition, through their own logistical caution. Weeks earlier, half their supply was moved back to keep it safer. Now there was no way to bring it back; any trucks on the road fell easy prey to roaming Allied fighter-bombers. Even small-arms ammunition began to run out. Orders from the German high command to counterattack went unheeded just as the local defender’s begged for reinforcements. With the weather clearing, Allied planes made their presence felt and little help arrived for the Germans.

In the late afternoon, the division headquarters and the 26th Regiment landed. The beach still received fire from a handful of undestroyed strongpoints and the odd round of artillery; even a few snipers lurked, firing occasional shots at the newly landed troops. It remained dangerous, as many men found to their sorrow, but the troops got ashore with much lighter casualties and were able to get off the beach quickly.

There remained the tasks of supplying the troops ashore, digging in for the night, and reorganizing from the chaos of the day.

As the sun set over Omaha Beach and the new battlegrounds above, GIs crouched in their foxholes, served as sentries, and tried to prepare for another grim day ahead. There would be many more days and months of fighting for the Big Red One before the war ended. At high cost, they had punched through the walls of Hitler’s “Atlantic Fortress” and paved the way for hundreds of thousands of Allied troops to follow in the coming weeks.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments