By Todd Raffensperger

“I submit that it was the wrong decision. It was wrong on strategic grounds. And it was wrong on humanitarian grounds.” It could be assumed that such a statement, pertaining to the decision by President Harry S. Truman to order the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, would come from an academic studying the whole issue of the atomic bomb, or perhaps part of a speech given by a peace activist. But the fact that it was a United States naval officer, a rear admiral in fact, is what makes the career of Ellis M. Zacharias intriguing.

He had made this statement in an article he wrote for Look magazine in 1950, five years after the bombs had been dropped, four years after he had retired from a career that spanned more than three decades. He was a hero, but a sad one of sorts. A hero for doing what he did to try to compel the Japanese government to surrender and stop a futile, unwinnable war, but sad because he could not do so in time to stop the horrific bloodshed that would mark the final days of the crumbling Japanese Empire. Sad that he could not curb the suffering of a people he had come to know, admire, and love.

A Young Man With a Passion for the Navy

Ellis Zacharias could remember, as he wrote in his memoirs, how he first decided to join the Navy, as an 8-year-old son of a tobacco grower in Jacksonville, Florida, watching the gray vessels of the U.S. Naval Patrol fleet steaming off Florida’s shores in 1898, ready just in case the Spanish, with whom the United States was at war at the time, should decide to randomly shell the American coastline. It was an exaggerated threat, but one that helped to implant the idea of serving on the high seas in the mind of the young Zacharias. At 18, he got the chance to follow his dream of attending the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis.

It was on his posting as an engineering officer aboard the battleship USS Virginia in 1913 that he made the first choice that would guide his career. The young ensign struck up a friendship with a lieutenant named Fred Rogers who at the time had the distinction of being the only officer in the U.S. Navy who was fluent in Japanese. Their lunchtime conversations ignited a fascination with the Far East and with Japan in particular. Eventually, both men completed their tours on the Virginia and were reassigned elsewhere, but Rogers kept the name of Ellis Zacharias in his head.

Naval Attaché in Japan

Seven years later, as Zacharias was stationed in Honolulu, he received a dispatch from Rogers, who by then was working for the Office of Naval Intelligence, with an offer that Zacharias could not turn down. “The Navy has decided to send two language officers to Japan,” read the dispatch. “Do you still desire to go?” His reply was prompt and without hesitation. “Your message, affirmative.”

In October 1920, Zacharias arrived in Tokyo to serve with the American embassy as a naval attaché, but his responsibilities went beyond just naval matters. The truth was that by the 1920s naval planners in Washington, D.C., were considering the possibility of war with the Japan. Zacharias’s assignment was not only to learn the Japanese language, but also to learn as much as he could about Japanese culture and society. Zacharias tackled this assignment with both zeal and fascination, learning as much about the Japanese as he could and developing a deep admiration for a nation that he someday would be called upon to fight.

On September 1, 1923, Zacharias found himself in the middle of one of the most horrific natural disasters in Japan’s history. The Kanto earthquake hit Tokyo and the Kanto region just before noon and ruptured water mains and natural gas lines throughout Tokyo and Yokohama. Hundreds of fires broke out but the fire department was powerless to stop the flames. In one horrific day, 104,000 Japanese lost their lives. Zacharias worked throughout the night doing what he could to help the survivors.

In his memoir, Secret Missions, he wrote, “The greatest weakness of the Japanese was their inherent psychic inertia in the face of disaster.” He observed this inertia in how Japanese officials acted or failed to act during the height of the disaster of September 1. With the city government in chaos, the earthquake and subsequent fires did more damage and claimed more lives than they should have. As a naval intelligence officer, Zacharias concluded, “This would also be the pattern of Japanese behavior in a supreme crisis of war when the unexpected happened.” Even then he could not have imagined how right he would be.

Zacharias left Japan with a deeper understanding of the Japanese culture, with a commanding knowledge of the Japanese language, and friendships with several Japanese officials, both civil and military. The extent of his connection with the Japanese government was apparent in 1931 when he was selected as aide to Emperor Hirohito’s brother, Prince Takamatsu, when he came to the United States on a goodwill tour.

As war became more likely during the 1930s, Zacharias’s duties had less to do with goodwill than with analysis and assessment. He spent a good deal of his time at sea monitoring the communications and movement of the Japanese Navy. The friendships he maintained with various Japanese officials enabled him to assess the growing strength of militarism in Japan and the near impotence of the moderates and even the emperor himself to keep the militarists in check. By the end of the decade, while Japan invaded China and war had broken out in Europe, Zacharias was posted stateside as an intelligence officer with the 11th Naval District, which covered the southwestern United States.

“Hear Three Times, Believe”

On February 7, 1941, Zacharias got the chance to meet an old friend, Admiral Kichisaburo Nomura, Japan’s new ambassador to the United States. It was not just a social call. Zacharias was to pry out of Nomura any information that he could about the Japanese perspective. It did not take much prying. At this point, the United States and Great Britain were imposing an oil and steel embargo on Japan in response to its invasion of China, and nerves were fraying on both sides of the Pacific.

Nomura confided to Zacharias that his purpose was to try to lift the embargo and get the United States to help Japan extricate itself from China without any loss of face. Nomura also believed that unless the embargo was lifted war between America and Japan was inevitable and that such a war would almost certainly mean the destruction of Japan as a major power. Zacharias felt for his old friend, but he knew that the chances of the embargo being lifted were slim.

As he considered what Japan’s next move would be, Zacharias remembered a Japanese proverb: “Hear three times, believe.” He concluded that the Japanese would send three emissaries with three messages to Washington—three warnings about the consequences of maintaining the embargo. If nothing were to change by the third emissary, the Japanese government would decide to go to war. Nomura was the first of these emissaries. Nine months after Zacharias’s conversation with Nomura, the newly appointed Japanese prime minister, General Hideki Tojo, sent another emissary to Washington, Ambassador Saburo Kurusu. At the end of November 1941, Japan’s ambassador to Peru, Tatsuki Sakamoto, arrived in Washington. He was in fact that third and final emissary, as Zacharias had predicted.

World War II Comes to America

The final days of peace for the United States found Zacharias at sea, commanding the heavy cruiser USS Salt Lake City. On December 7, 1941, the Salt Lake City was in company with a task force under the command of Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey.

Zacharias was in his cabin, but he was far from asleep. He already knew of a Japanese submarine sighting off the southern coast of the Hawaiian islands. The ship’s radio equipment had picked up scrambled, but unmistakable to his trained ear, Japanese messages being exchanged. He knew something was up. Shortly after 8 am, he found out what was going on when his communications officer burst into his cabin exclaiming, “They’re bombing Oahu!”

The radio reports were sketchy, and no one in the fleet had any clue as to the true extent of the damage that had been done to the Pacific Fleet. It became apparent soon enough when Halsey’s task force entered the burning harbor. Zacharias noted that from the very beginning of the war, and in spite of its meager resources, the Japanese fleet was imbued with a spirit of the “ruthless offensive,” to attack and seize the initiative by whatever means possible.

On February 1, 1942, Zacharias’s command was involved with the raids by carrier-based aircraft against the Gilbert and Marshall Islands. The Salt Lake City shelled Wojte Atoll although she inflicted little damage. In April, Zacharias was part of the first attack on the Japanese mainland as his cruiser provided escort for the air carrier USS Hornet as she launched Lt. Col. James Doolittle’s B-25 bombers against Tokyo.

Deputy Director of Naval Intelligence

While Zacharias’s leadership and command skills were outstanding, it would be his knowledge of the Japanese language and of the Japanese people, as well as his background in intelligence, that would prove to be far more valuable to the War Department. In June 1942, he was reassigned to Washington as deputy director of Naval Intelligence with OP16W, the code designation for the ONI, Office of Naval Intelligence. While many of his fellow naval commanders may have disagreed, Zacharias had come to believe that the dastardly art of intelligence and psychological warfare could prove to be decisive in winning this war, and winning it with a minimal loss of life. But he would have more than the Japanese to contend with. The American military bureaucracy sometimes seemed to be a foe as well.

When Zacharias was appointed to the position, Admiral Ernest J. King, the chief of naval operations, had tasked him with the job of creating a first-class intelligence-gathering organization that coordinated all the efforts of various agencies in the United States government. Getting the resources to build up this organization was not the problem; wartime Washington was abundant with funding and personnel. The trick was finding the right people with the right qualifications, and doing so would require someone who would not be intimidated by the oppressive bureaucracy. Zacharias filled the bill.

Through hard work and determination, Zacharias was central to the creation of the Joint Intelligence Collection Agency (JICA), whose purpose was the gathering of reconnaissance and tactical intelligence information that could be used by all the branches of the military. Such teams were assigned to North Africa and the Mediterranean to collect information helpful in planning the invasion of Europe. Before JICA, it had been extremely difficult for the Navy and the Army to share information from their intelligence agencies.

With an American naval officer personally doing the broadcasts under the pseudonym of Commander Robert Lee Norden, Naval Intelligence and the Office of War Information (OWI) ran a series of radio programs specifically targeting the officers and crews of German U-boats. Such programs would report the statistical odds of a German sailor being killed aboard a U-boat or broadcast that the shipping tonnage being sunk was grossly inflated by the German high command. Some programs went so far as to give advice to sailors on how to fake certain ailments that would get them out of sea duty.

Naval Intelligence also sought to use the programs to water the seeds of distrust between the Germans and Italians. When the North African campaign was coming to an end, Commander Norden gleefully reported that Italian ships were being directed by the Germans to evacuate the remnants of the Afrika Korps, giving the remaining Italian troops secondary priority. Just as Zacharias was making plans for a similar propaganda operation in the Pacific, he went to sea again.

“A Strategic Plan to Effect the Occupation of Japan”

His new assignment was command of the battleship USS New Mexico. With Zacharias in command, the old battleship participated in operations to capture Makin Atoll in the Gilberts and the islands of Guam and Saipan in the Marianas. Throughout the bloody months of 1943 and 1944, Zacharias paid close attention to Japanese radio broadcasts and took note of the fact that Tojo himself seemed to be conceding the possibility that the Japanese could lose the war.

On September 14, 1944, Zacharias was relieved of his command after just over a year. For his actions, he was awarded the Navy’s Gold Star. He had reason to be proud of his service, but now events convinced him that it was time to play a different role in winning the war in the Pacific. Shortly after the fall of Saipan, Tojo’s government was dismissed by Emperor Hirohito. Tojo’s dismissal was the first indication that Japanese morale was beginning to crack.

At this time, Zacharias was assigned once again to the 11th Naval District, and as 1944 drew to a close, it became apparent to almost everyone in the intelligence community that there were those in the imperial government who were looking for a way out of the war. Zacharias believed that the time was ripe to help those in the antiwar camp in Tokyo to finally convince the rest of the government that the time had come to surrender. His ideas to achieve this result were encapsulated in a comprehensive, two-part strategy of psychological war that he drew up in December to submit to Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal. Its official designation was Operational Plan No. I-45, titled “A Strategic Plan to Effect the Occupation of Japan.”

As Zacharias described it, the plan proposed to hit the Japanese government from two directions, above and behind. No bombs, bullets, or troops would be needed. From the air, he proposed a deliberate and overt psychological campaign that would consist of everything from radio broadcasts to air-dropped leaflets that the average Japanese could read in order to understand the American position and to promote the arguments of the pro-peace members of the government. From behind, the plan called for the use of clandestine operations and back-channel overtures to compel Japan’s leaders to surrender.

The idea of a plan to bring the Japanese to surrender without a shot being fired did not endear itself to most officials in Washington. Americans were aware of some atrocities that the Japanese had committed, and Pearl Harbor was still a bitter memory. Nobody in Washington was in any mood for a peaceful settlement of the conflict with Japan. Forrestal, however, believed in Zacharias’s plan, not only because he was open-minded enough to consider its possibilities, but also for global political reasons. Forrestal knew that the Soviet Union was going to declare war on Japan with the goal of seizing key territory in Asia and having a foothold in the Pacific. He was hoping that Zacharias’s plan could shorten the war before the Russians joined in. Forrestal formally approved the plan on March 19, 1945.

A Soft Propaganda Approach

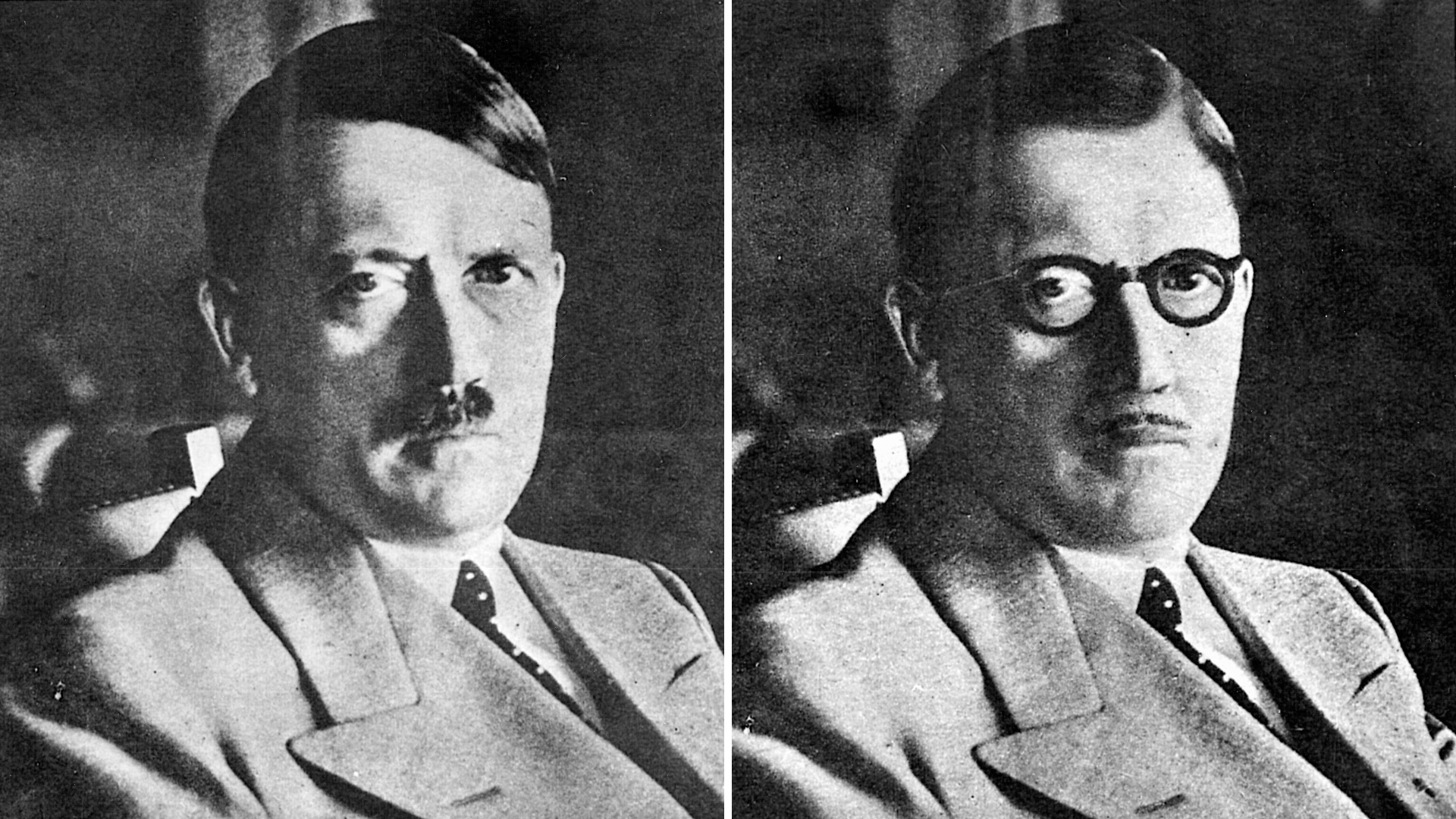

The voice of Captain Ellis M. Zacharias came over the airwaves on May 8, 1945. In this and in every subsequent broadcast, he would describe himself as the “official spokesman” of the United States government, and while he was never officially designated as such, no one in Washington objected to his using the term. On the day that Nazi Germany officially surrendered unconditionally, he used the occasion as a springboard for what would be a continued psychological campaign that would target the decision makers in the Japanese government. His broadcasts were carried on the Saipan transmitter once each week on the Radio Tokyo broadcast band to ensure that they could not be censored and that every Japanese citizen with a radio would hear them and understand exactly what was being said to their leaders.

Unlike most other propaganda programs, Zacharias’s tone and approach were much more civil, sometimes even informal. It was not uncommon for him to mention the names of Japanese friends and acquaintances that he had made during his time in Tokyo. He sent regards to them or expressed condolences to the families of those he knew had been killed in action. However soft or civil the tone, the basic message to the Japanese was the same—that the time had come for the leaders of Japan to bring the increasingly bloody and useless war to an end. He argued that the only real option was to surrender.

The two words “unconditional surrender” proved to be major stumbling blocks to peace in the Pacific. While the peace faction in Tokyo was pushing for an immediate end to the war, the war faction was very much afraid of the implications of this phrase, which conjured up images of an entire nation enslaved, helpless, crushed under the conqueror’s boot, and of an emperor dishonored, humiliated, and even imprisoned.

Zacharias believed there was still a chance to convince the hawks in the Japanese government that surrender was an acceptable alternative. The Japanese, he argued, could accept the idea of an unconditional surrender, but only if the implications and specifics of such surrender were made clear to them. They had to understand that an unconditional surrender did not mean enslavement or annihilation of the Japanese people.

Finding a Back Channel to Tokyo

It was not just by radio that Zacharias intended to make this point. As the air war phase of Zacharias’s plan went on week by week, his team was pursuing a back channel to Tokyo. One of the more off-the-wall ideas was to deposit the naval officer and Hollywood film star Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., onto the shores of Japan to contact those in the government willing to negotiate. Fairbanks was no stranger in Japan, especially to the imperial court, with which he had established many friendships. The idea was bizarre and extremely dangerous, but it appealed to Fairbanks. Admiral King nixed the plan as being too dangerous.

Another idea involved using General Hiroshi Oshima, who had been the Japanese ambassador to Nazi Germany until his capture by American troops. Zacharias felt that Oshima, the highest ranking Japanese prisoner of the Americans, could help persuade his more reluctant comrades to accept unconditional surrender. Oshima had been one of the staunchest supporters for Japan’s adherence to the Axis, but when contacted by Zacharias he was willing to cooperate. Before arrangements could be made to bring him to the United States, the Army moved Oshima to an undisclosed location and kept him beyond the reach of ONI. The Army never explained why it took this step, but after the war Zacharias expressed his belief that it was an attempt to sabotage his plan, which it effectively did.

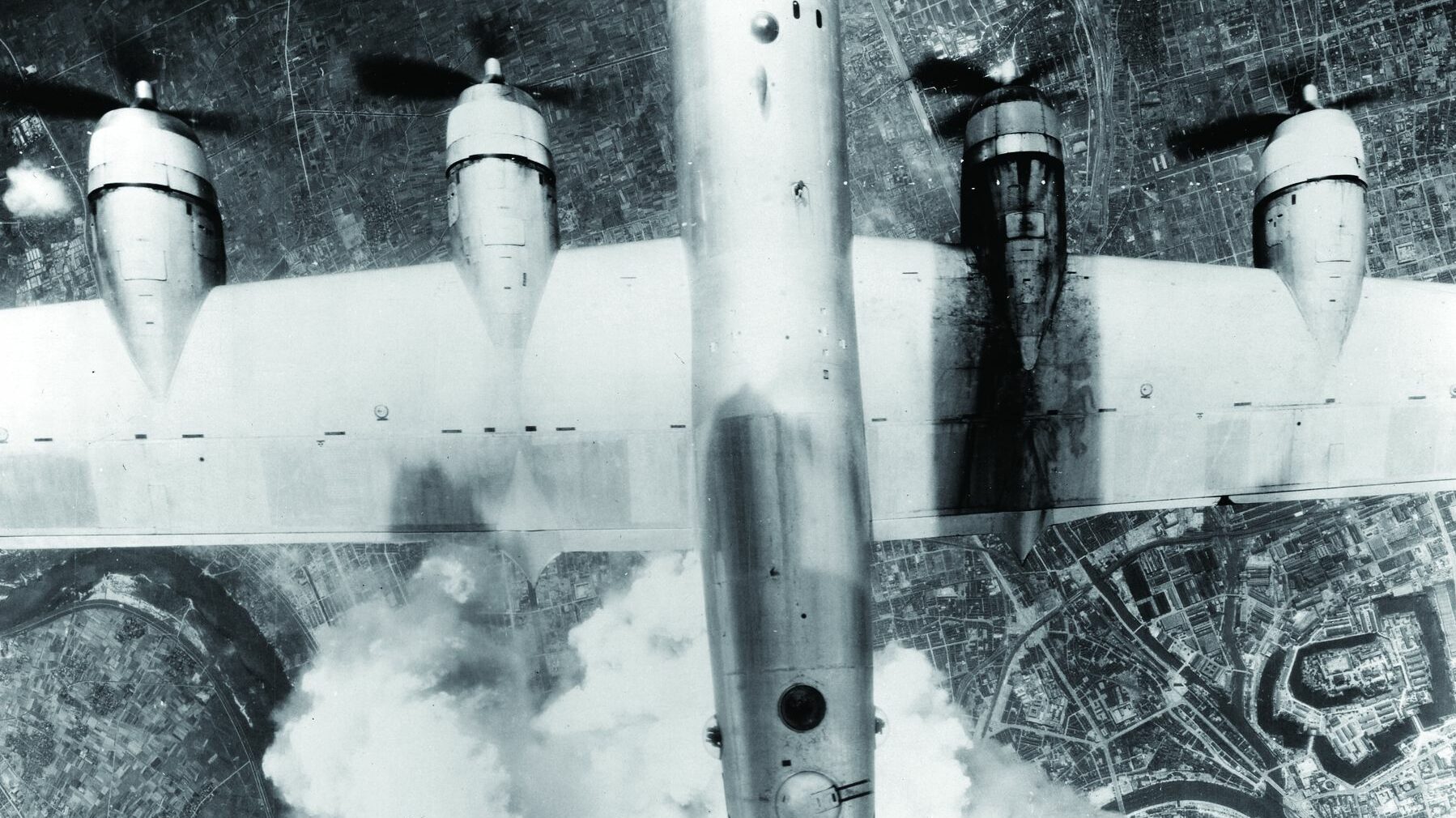

The most serious and promising effort to find a back channel was actually started by Emperor Hirohito himself, when he made a direct appeal to Pope Pius XII to intervene and mediate negotiations between Japan and the Allied powers. While this first effort came to no avail, Zacharias and his team still saw the possibility of using the good offices of the Vatican. ONI contacted Cardinal Pietro Fumasoni-Biondi as a possible intermediary. It seemed that the Allies and the Japanese were getting close, but it turned out to be a forlorn hope. Not long after agreeing to help Zacharias, Cardinal Fumasoni-Biondi told ONI that he had been warned by “certain people” in Washington not to take part in this endeavor. This effectively ended the last effort by Zacharias to open indirect negotiations. In early 1945, Zacharias was unaware of the atomic bomb, but he did know that the last act of the Pacific War was at hand. Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers were conducting massive raids on Japanese cities.

Bringing the Atlantic Charter to the Pacific

The men guiding America’s foreign policy had concluded that there was no viable way to end the Pacific War with a minimal amount of bloodshed. Backing down from the position of unconditional surrender was never an option, not with all that had happened in the past four years, and the Japanese, they believed, should not be treated any differently from their erstwhile allies, the Germans.

But Zacharias believed that there was an alternative. His knowledge and experience with the Japanese led him to believe that it was possible to compel the Japanese government to surrender without compromising Allied principles and without ending the drama of the Pacific War with a last bloody episode. The key to his hope was the Atlantic Charter, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill early in 1941.

The Atlantic Charter stated eight basic points concerning the rights of nations and their peoples and was in many ways a precursor to the United Nations Charter. The document notes the intention of the United States and Great Britain to seek “no aggrandizement, territorial or other,” in the struggle against Nazism. Nor did they seek any territorial changes of any state or nation. They called upon the nations of the world to denounce the use of force in solving their problems. While the charter had been intended for the struggle in Europe, Zacharias saw a chance to apply its provisions to the Pacific Theater.

Unconditional Surrender or Virtual Destruction

If, as Zacharias hoped, the Japanese believed that such terms could apply to them, that unconditional surrender would not mean the destruction and enslavement of the Japanese people nor the end of the status of the emperor, then they might agree to unconditional surrender. All that needed to be done was to communicate this point to Tokyo. But to do so entailed a certain degree of risk to Zacharias and his career.

July 21, 1945, was the date selected. It would be his 12th broadcast to the Japanese people and their leaders; it also was the date that President Truman would meet with Churchill and Soviet Premier Josef Stalin for the first time at Potsdam. As the leaders sat down to hash out their differing visions for a postwar world, Zacharias went on the air with the bluntest delivery he had made yet to the Japanese. “Japan has already lost the war. Your progressive defeats and our progressive victories have brought the war to Japan’s very doorstep,” he said.

But Zacharias went further, laying blame for Japan’s misfortunes on the government itself and stating that they, the leaders of Japan, from the emperor on down, were “entrusted with the salvation and not the destruction of Japan.”

For his climactic statement, Zacharias put forward the basic choice, the only choice that Tokyo had left at this point: “The Japanese leaders face two alternatives. One is the virtual destruction of Japan followed by a dictated peace. The other is unconditional surrender with its attendant benefit as laid down by the Atlantic Charter.” As he admitted later, he had no authorization to say it and had no clearance on any level to say it. He did not even let anyone beyond his team know that he would say it.

Like everything else he had said, these words were to have a calculated effect, and what an effect it was. The day following the broadcast, almost every major newspaper in the United States covered the story that Ellis Zacharias, the “official spokesman” for Washington, had given the Japanese a way out. The New York Times ran the headline, “Japan Is Warned to Give-Up Soon: U.S. Broadcast Says Speed Will Bring Peace Based on the Atlantic Charter.” The Baltimore Herald ran a similar headline, “Japan Told to Surrender Unconditionally or Face Inevitable Destruction: Official Broadcast Bids Enemy Leaders Yield Under Atlantic Charter.” But support for this move was not universal. While some people cheered Zacharias’s statement, others condemned him for weakening the American position on unconditional surrender. Some were of the opinion that Zacharias had overstepped his authority and should be relieved of his duties.

Forrestal spread the word that Zacharias’s actions met with his approval, merely articulating the established policy of the president of the United States. Then Forrestal telephoned Potsdam to get Truman’s belated authorization for the broadcast. He followed this up by flying to Potsdam himself to confer with the president. Eventually, his persuasion worked, and Truman authorized the Associated Press to report that he “tacitly” approved of the July 21 broadcast.

The Potsdam Declaration

There was no immediate word from Tokyo about the broadcast. Then, on July 24 the airwaves crackled with the first official statement from the Japanese government. It was delivered not by a propagandist or a military officer, but by an intellectual, Dr. Kiyoshi Inouye, a professor considered one of Japan’s foremost authorities on international relations and an acquaintance of Zacharias.

In reference to the offer of surrender on the terms of the Atlantic Charter, Inouye replied, “Should America show any sincerity of putting into practice what she preaches, as, for instance, in the Atlantic Charter, excepting its punitive clause, the Japanese nation, in fact, the Japanese military would automatically, if not willingly, follow in stopping the conflict. Then and then only will sabers cease to rattle both in the East and the West.” Whether Inouye’s statement would truly be met with support, albeit reluctantly by the Japanese Army, is still in question. But the statement itself, carried on Japanese government radio, was extraordinary.

On July 26, 1945, the Allied leaders produced their first statement of intentions for the postwar world in the Potsdam Declaration. Sure enough, the Allied powers expressed their assertion that the Japanese people would not be enslaved or destroyed, but beyond this there was no assurance about the status of the emperor or of Japan’s status as a nation. What was apparent in the document was that the United States was not about to deviate from the Allied terms of unconditional surrender.

The document stated that the Allies would maintain a military occupation of Japan until there was “convincing proof that Japan’s war-making power is destroyed.” Freedom of speech, religion, and respect for fundamental human rights would be established in postwar Japan. The Allies declared their determination to punish all those in the Japanese government responsible for the war. The document concluded with a final stern warning that Japan surrender unconditionally. Its only alternative was “prompt and utter destruction.”

Years later, Zacharias wrote with more than a tinge of bitterness, “The Potsdam Declaration, in short, wrecked everything we had been working for to prevent further bloodshed and insure our postwar strategic position.”

The Unconditional Surrender That Never Was

After Potsdam, Zacharias made two more broadcasts to Japan, a last-ditch bid to persuade the Japanese government that they had to agree to the terms laid down at Potsdam, that time was running out, and that the threat of “utter destruction” was not idle rhetoric. On August 4, 1945, he delivered his last broadcast, warning the Japanese to “plan for their inevitable defeat, and for Japan’s future, with whatever loyalty, intelligence, and courage they can still command.”

In a final touch of irony, following the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Japanese government agreed to surrender only if the Allies promised to spare the emperor, which surprisingly the Truman administration did. Ultimately, the “unconditional surrender” that the Japanese finally accepted was not unconditional in the purest sense of the word.

Ellis M. Zacharias retired with the rank of rear admiral in 1946, concluding a 30-year career with the United States Navy. He received a second Gold Star for his radio broadcasts. He never stopped advancing the case for the importance of psychological warfare programs as a means of both shortening a war and winning it with a minimal amount of bloodshed.

Until his death in 1961, he believed that Japan might have surrendered without an invasion or the use of the atomic bomb.

It amazes me sometimes how parochial people can be.

All this whining and crying about two bombs that destroyed much of two cities. I understand the reaction because of the massive destruction from only two weapons.

What I don’t understand is the almost total lack of concern about the fire bombing raids. Gen Lemay bragged about the hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians he burned to death in the more than 50 cities he burned down. The Air Force thinks of him as a great hero while Truman is castigated for two atomic bombs. Not much balance here.

These two bombs finally gave the Japanese emperor the excuse he needed to surrender while Lemay proudly planned to burn some 10-20 more cities.